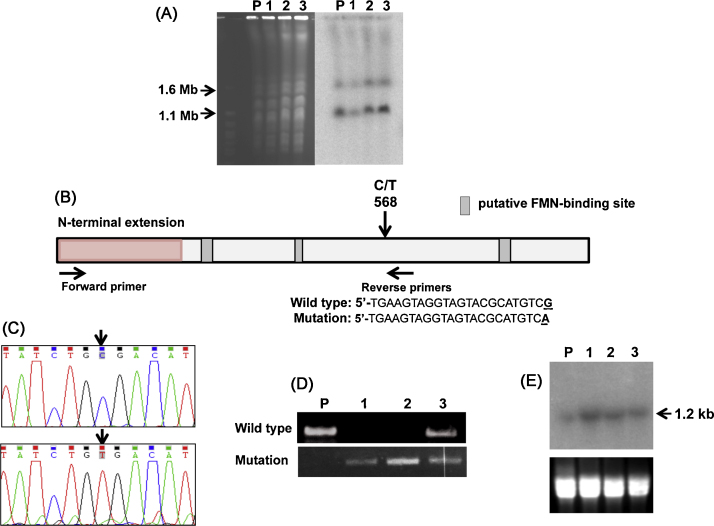

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the structure and expression of the TcNTR gene from benznidazole-resistant parasites. (A) Chromosomal DNA from the parental T. cruzi Y strain (P) and three drug resistant clones (1–3) was immobilised in agar blocks and fractionated by a Bio-Rad CHEF Mapper system using an auto-algorithm set to the designated molecular mass range [12] (left hand image). Chromosomes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) were used as molecular mass standards. After Southern hybridisation using a radiolabelled TcNTR probe, the membrane was autoradiographed (right hand image). (B) Schematic of the TcNTR gene showing the region corresponding to the N-terminal extension and putative FMN-binding regions [8,16]. The position of the C/T transition that generates a stop codon and the locations of primers used to differentiate between wild type and mutated genes are shown, together with the sequence of the reverse primers. (C) Electropherograms identifying the C/T transition in wild type (upper) and mutated (lower) genes (GenBank accession number KF731779). (D) Products generated following amplification of the TcNTR gene fragment using the primers shown in (B). PCRs were carried out using 30 amplification cycles; 96 °C for 30 s, 70 °C (wild type reverse primer) or 65 °C (mutation-containing reverse primer) for 30 s, 72 °C for 90 s, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. Upper inset, wild type reverse primer; lower inset, mutant reverse primer. (E) Northern blot analysis of RNA from T. cruzi Y strain (P) and three drug resistant clones (1–3). Upper inset, autoradiograph following hybridisation with radiolabelled TcNTR probe; lower inset, ethidium bromide stained gel as loading control.