Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to develop a brief knowledge survey about chronic non-cancer pain that could be used as a reliable and valid measure of a provider’s pain management knowledge.

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional study design. A group of pain experts used a systematic consensus approach to reduce the previously validated KnowPain-50 to 12 questions (2 items per original six domains). A purposive sampling of pain specialists and health professionals generated from public lists and pain societies was invited to complete the KnowPain-12 online survey. Between April 4 and September 16, 2012, 846 respondents completed the survey.

Results

Respondents included registered nurses (34%), physicians (23%), advanced practice registered nurses (14%), and other allied health professionals and students. Twenty-six percent of the total sample self-identified as “pain specialist.” Pain specialists selected the most correct response to the knowledge assessment items more often than did those who did not identify as pain specialists, with the exception of one item. KnowPain-12 demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability (alpha = 0.67). Total scores across all 12 items were significantly higher (p < .0001) among pain specialists compared to respondents who did not self-identify as pain specialists.

Discussion

The psychometric properties of the KnowPain-12 support its potential as an instrument for measuring provider pain management knowledge. The ability to assess pain management knowledge with a brief measure will be useful for developing future research studies and specific pain management knowledge intervention approaches for health care providers.

Keywords: Education, Measure, Physician Knowledge, Pain

INTRODUCTION

Health care provider knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) surveys are commonly used for a variety of purposes in pain education and quality improvement initiatives. These tools can be used to alert an individual to a personal knowledge or practice gap, to assess a group’s needs for further global education program or resource planning, and to evaluate the direct impact of an educational program on gains in knowledge when used as a pre- and post-test. The use of pain KAP surveys has revealed that physicians often have poor knowledge of pain and controlled substances, and that this affects their practice (1-5).

Many versions of pain KAP surveys exist, but nearly all stem from two seminal instruments: the City of Hope’s Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain (6) and the Cancer Pain Role Model Program Questionnaire (7). Both surveys have been updated at various times since they were first developed more than 20 years ago. However, the majority of individual test items continue to focus on cancer or acute pain and the palliative use of opioids, raising questions about test validity for chronic non-cancer pain management knowledge. As a result, the use of pain KAP surveys with primary care physicians has been limited. The knowledge required for physicians to manage chronic non-cancer pain and long-term opioid therapy in the primary care setting may be in sharp contrast to that of acute or cancer pain management.

Additionally, the available surveys, including the University of Toronto’s Pain Knowledge and Beliefs Questionnaire (PKBQ) (8) contain 35 to 45 individual questions, making them burdensome to take. Surveys of this length may require upward of 30 minutes or more for completion, leading to survey fatigue. Busy clinicians rarely have the time or willingness to complete lengthy surveys following brief continuing education programs. While the optimum number of survey items is unknown, survey fatigue, as defined by the time and effort involved in participating in a survey, has been linked to increases in nonresponse rates (9).

The KnowPain-50 is a 50-item test that was developed in 2007 for two reasons: to respond to concerns about the validity of existing KAP surveys, and to develop a test that could be standardized for chronic non-cancer pain (10). To develop the KnowPain-50, first an outside panel of experts in pain management was convened to draft a 142-item survey covering the construct of chronic pain as a biopsychosocial disorder that requires a multimodal approach to assessment and management. The authors used a predefined psychometrically based technical plan to specify acceptable item difficulty levels and discrimination indices for retaining survey items that were described elsewhere. Then a four-stage refinement process, which compared the results of the survey with findings from unannounced visits by standardized patients with chronic pain in general internal medicine and family medicine practices, was used to finalize a 50-item survey (9). The resultant KnowPain-50 survey included items that covered the following six domains: (a) initial pain assessment; (b) definition of treatment goals and expectations; (c) development of a treatment plan; (d) implementation of a treatment plan; (e) reassessment and management of longitudinal care; and (f) management of environmental issues.

The KnowPain-50 was found to have high internal consistency (alpha) across all populations studied (0.77–0.85), to have correlations with clinical behaviors, and to distinguish among physicians with different levels of pain management expertise. Finally, the differences in KnowPain-50 scores following participation in educational programs appeared to persist for at least 3 months (11). However, like its counterparts, the KnowPain-50 is lengthy and may be considered burdensome for test takers. It has been our experience that when the KnowPain-50 is sent to participants of a University of Washington video-teleconferencing program (UW TelePain), the response rate is low due to respondent burden.

The purpose of this study was to develop and test a brief knowledge survey that could be used as a reliable and valid measure of provider knowledge of chronic non-cancer pain as part of a study examining the impact of a video-teleconferencing pain consultation program. Specifically, this study sought to extend previous work (10), reduce the number of KnowPain-50 items, and then assess the internal consistency, reliability, and face, content, construct, and discriminative validity of the brief form in a heterogeneous group of physicians and nurses. We hypothesized that scores on the new survey, now termed KnowPain-12, would be higher for providers who self-identified as pain management specialists compared to the scores of providers who did not.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was reviewed and granted Category 2 exemption by the University of Washington’s Human Subjects Division, as this research involved an education survey test.

Phase I. KnowPain-12 Development

A structured consensus approach was used to develop a briefer test that would retain all major domains of the construct of chronic non-cancer pain contained within the KnowPain-50, reduce the number of items, and establish content and face validity. Nine experts in chronic non-cancer pain management, identified locally and from previous published work on pain knowledge surveys, were asked to review the KnowPain-50 and to identify three items they felt best reflected each of the original six domains of knowledge described above. The experts included five physicians and four nurse scientists. Of note, the participating experts were asked to group their responses under domain headings in the absence of an available KnowPain-50 factor analysis that would have provided a discrete list of domain items. Consensus group members were instructed to vote only on items that asked for a level of agreement with a statement; five multiple-choice questions were thus eliminated. Individual responses were then compared for agreement. Items with the highest level of agreement were kept, resulting immediately in a final pair of items for two domains (development and implementation of a treatment plan). Three items were initially retained in two of the remaining domains (initial pain assessment, and reassessment and management of longitudinal care), and four items were initially retained in each of the remaining domains (definition of treatment goals and expectations, and management of environmental issues). Four of the authors (DG, JL, DT, AD) reviewed results and made the final selection of item pairs for the four domains that needed additional item reduction. Decisions were based on face validity of distinct domains and discussion to resolve discrepancies and reach consensus on which items had the most clear, correct answers. Reasons provided for judgments of inclusion and exclusion criteria were debated in a face-to-face meeting.

As with the original KnowPain-50, a six-category Likert-type scoring scale that provides graded points for a correct answer was used in order to be sensitive to changes in expertise and confidence. Available answers range from strongly agree, agree, and somewhat agree to somewhat disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree. The final set of 12 survey statements (see Table 1) includes eight items with agreement and four with disagreement as correct responses. For scoring, items were coded so that the most extreme correct response was assigned 5 points and the most extreme incorrect response 0 points, yielding a possible total scoring range of 0–60. Items in the new KnowPain-12 were ordered by domain.

Table 1.

KnowPain-12 Survey Items

| 1. When I see consistently high scores on pain rating scales in the face of minimal or moderate pathology, this means that the patient is exaggerating his/her pain. |

| 2. In chronic pain, the assessment should include measurement of the pain intensity, emotional distress, and functional status. |

| 3. There is good evidence that psychosocial factors predict outcomes from back surgery better than the patient’s physical characteristics. |

| 4. Early return to activities is one of my primary goals when treating a patient with recent onset back pain. |

| 5. Antidepressants usually do not improve symptoms and function in chronic pain patients. |

| 6. Cognitive behavioral therapy is very effective in chronic pain management and should be applied as early as possible in the treatment plan for most chronic pain patients. |

| 7. I feel comfortable calculating conversion doses of commonly used opioids. |

| 8. Long-term use of NSAIDs in the management of chronic pain has higher risk for tissue damage, morbidity, and mortality than long-term use of opioids. |

| 9. There is good medical evidence that interdisciplinary treatment of back pain is effective in reducing disability, pain levels, and in returning patients to work. |

| 10. I believe that chronic pain of unknown cause should not be treated with opioids even if this is the only way to obtain pain relief. |

| 11. Under federal regulations, it is not lawful to prescribe an opioid to treat pain in a patient with a diagnosed substance use disorder. |

| 12. I know how to obtain information about both state and federal requirements for prescribing opioids. |

Phase II. KnowPain-12 Pilot Test

The KnowPain-12 was then pilot tested at an anesthesiology department faculty retreat with a group of three board-certified pain specialists and eight anesthesiologists who did not specialize in chronic pain management. The goal was to observe for differences in responses and gain general feedback from participants about the survey. Differences in correct answers and degrees of confidence were noted between self-identified pain specialists and nonspecialists. Feedback primarily included suggestions for minor wording changes on several survey items; however, in order to stay consistent with the KnowPain-50 sentence structure, no changes were made.

Phase III. Testing of KnowPain-12

Participants

A list of potential participants to invite to test the KnowPain-12 was generated from directories of all departments within the University of Washington’s School of Medicine and School of Nursing, the American Pain Society’s special interest groups, and the American Society of Pain Management Nurses.

Procedure

An email with a link to a Catalyst WebQ survey was then sent inviting all to participate by completing the test online. The Catalyst online survey tool has previously been determined by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division to provide acceptable procedures to protect the privacy and confidentiality of human subjects. Details on privacy protection for Catalyst are available at http://www.catalystanalytics.com/privacy-policy/. Additionally, a convenience sample of students from one graduate nursing course at the University of Washington were verbally invited to participate by the course instructor during class; the students completed the survey on paper. A precise invited sample-size total was not possible to compute, but known tallied numbers exceeded 3,000.

Measures

For items on the KnowPain-12, if a correct answer of strongly agree was selected, this answer received 5 points; if agree was selected, 4 points; and so on to 0 for the sixth and most incorrect response. Items 1, 5, 10, and 11 (for which strong disagreement is the correct response) were coded so that the most correct response, strongly disagree, was assigned 5 points, and the least correct response, strongly agree, was assigned 0 points. The KnowPain-12 score was calculated as the sum of the 12 survey items. The KnowPain-12 score ranges from 0 to 60, with a higher score corresponding to more correct responses. In addition to participants’ answers of agreement with items on the KnowPain-12, information was collected on year of birth, sex, ethnicity, race, status as pain specialist, discipline, student status, and role (i.e., clinician, researcher, educator).

Statistical analysis

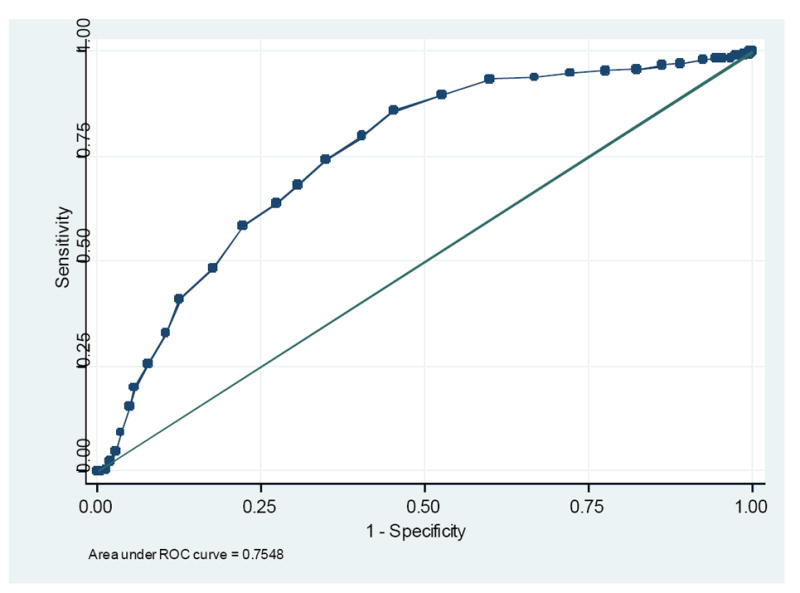

To verify that the KnowPain-12 score could discriminate between levels of pain management knowledge, we compared the average score among those who self-identified as pain specialists to that of those who did not, using a two-sample independent t-test. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the distribution of responses to individual KnowPain-12 items between the two groups. Additionally, we constructed a receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve for discriminating pain specialists based on the KnowPain-12 score. A ROC curve plots the sensitivity versus the false positive rate for different thresholds of the KnowPain-12 score. The closer the ROC is to the upper left corner, the greater the ability of the score to distinguish between the two groups (12,13). The internal consistency reliability of the KnowPain-12 score was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha statistic. Cronbach’s alpha is a conservative lower-bound estimate of the true reliability (the degree to which a test score can be repeated under the same conditions) but has been questioned as an appropriate measure for internal consistency (unidimensionality, or the degree to which items measure the same thing) (14). To assess dimensionality of the survey, we performed an exploratory principal axis factor analysis, retaining factors with eigenvalues ≥ 1. We used varimax rotation to obtain loadings (correlations) of items on factors. All analytical procedures were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp LP College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Between April 4 and September 16, 2012, 846 respondents completed the online KnowPain-12. Table 2 provides a description of the respondents based on self-report. The most common respondents included registered nurses (34%), physicians (23%), and advanced practice registered nurses (14%), followed by other allied health professionals and students. Among all disciplines combined, 26% (n = 214) self-identified as pain specialists.

Table 2.

Demographics of Survey Respondents (N = 846)

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 51 (11.6) |

| Gender | % (n) |

| Female | 74 (613) |

| Male | 26 (217) |

| Ethnicity | % (n) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (41) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 95 (784) |

| American Indian /Alaska Native | 1 (11) |

| Asian (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, or other Asian) | 5 (38) |

| Black/African American | 2 (14) |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (2) |

| White/Caucasian | 91 (757) |

| More than one race | 1 (12) |

| Unknown | 0 (2) |

| Other | 2 (13) |

| Type of student | % (n) |

| Medicine | 9 (7) |

| Nursing | 90 (74) |

| Pharmacy | 1 (1) |

| Pain specialist | 26 (214) |

| Role | % (n) |

| Clinician | 33 (277) |

| Educator | 24 (203) |

| Researcher | 13 (106) |

| Student | 7 (60) |

| Discipline | % (n) |

| Advanced registered nurse practitioner | 14 (116) |

| Pharmacist | 3 (23) |

| Physician | 23 (192) |

| Physician assistant | 1 (10) |

| Psychologist | 3 (22) |

| Registered nurse | 34 (283) |

| Other | 14 (102) |

Note: categories were not mutually exclusive and explain why totals do not always equal 100%.

Overall, responses to the KnowPain-12 heavily favored the most correct choice or the second most correct choice. The two most incorrect choices were the least frequent responses across all items. Examination of responses by whether or not the respondent self-identified as a pain specialist showed that pain specialists were more likely to select the most correct choice for 11 of the 12 items (see Table 3). The one item with the most incorrect responses by self-identified pain specialists (Item 3) and also the least discriminative asked for agreement that there is good evidence that psychosocial factors predict outcomes from back surgery better than a patient’s physical characteristics.

Table 3.

Responses to KnowPain-12 Survey Items by Pain Specialist Status

| All (N = 846) | Pain specialist (N = 214) | Not a pain specialist (N = 624) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | p-value | |

| Q1. When I see consistently high scores on pain rating scales in the face of minimal or moderate pathology, this means that the patient is exaggerating his/her pain. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree* | 28 (238) | 40 (85) | 24 (151) | |

| disagree | 37 (316) | 39 (84) | 37 (231) | |

| disagree somewhat | 14 (116) | 11 (24) | 15 (91) | |

| agree somewhat | 17 (142) | 9 (19) | 19 (120) | |

| agree | 3 (29) | 0 (1) | 4 (27) | |

| strongly agree | 1 (5) | 0 (1) | 1 (4) | |

| Q2. In chronic pain, the assessment should include measurement of the pain intensity, emotional distress, and functional status. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree | 2 (14) | 3 (6) | 1 (7) | |

| disagree | 0 (4) | 0 (1) | 0 (3) | |

| disagree somewhat | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | |

| agree somewhat | 1 (11) | 1 (2) | 1 (9) | |

| agree | 28 (239) | 17 (37) | 32 (199) | |

| strongly agree* | 68 (577) | 79 (168) | 65 (405) | |

| Q3. There is good evidence that psychosocial factors predict outcomes from back surgery better than the patient’s physical characteristics. | .562 | |||

| strongly disagree | 1 (7) | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | |

| disagree | 7 (55) | 9 (19) | 6 (36) | |

| disagree somewhat | 10 (87) | 10 (21) | 11 (66) | |

| agree somewhat | 31 (266) | 30 (65) | 32 (200) | |

| agree | 38 (320) | 39 (84) | 37 (232) | |

| strongly agree* | 13 (111) | 11 (23) | 14 (85) | |

| Q4. Early return to activities is one of my primary goals when treating a patient with recent onset back pain. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree | 1 (11) | 0 (1) | 2 (10) | |

| disagree | 4 (35) | 2 (5) | 5 (30) | |

| disagree somewhat | 3 (27) | 0 (1) | 4 (25) | |

| agree somewhat | 13 (112) | 10 (22) | 14 (89) | |

| agree | 41 (345) | 34 (72) | 43 (269) | |

| strongly agree* | 37 (316) | 53 (113) | 32 (201) | |

| Q5. Antidepressants usually do not improve symptoms and function in chronic pain patients. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree* | 22 (185) | 31 (67) | 19 (116) | |

| disagree | 46 (393) | 50 (108) | 45 (282) | |

| disagree somewhat | 20 (172) | 13 (27) | 23 (142) | |

| agree somewhat | 6 (52) | 4 (9) | 7 (43) | |

| agree | 4 (34) | 1 (2) | 5 (32) | |

| strongly agree | 1 (10) | 0 (1) | 1 (9) | |

| Q6. Cognitive behavioral therapy is very effective in chronic pain management and should be applied as early as possible in the treatment plan for most chronic pain patients. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree | 1 (12) | 1 (3) | 1 (9) | |

| disagree | 2 (21) | 0 (1) | 3 (20) | |

| disagree somewhat | 6 (54) | 4 (9) | 7 (45) | |

| agree somewhat | 24 (203) | 17 (37) | 26 (164) | |

| agree | 36 (302) | 30 (64) | 38 (235) | |

| strongly agree* | 30 (254) | 47 (100) | 24 (151) | |

| Q7. I feel comfortable calculating conversion doses of commonly used opioids. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree | 10 (87) | 2 (5) | 13 (82) | |

| disagree | 12 (103) | 5 (10) | 15 (91) | |

| disagree somewhat | 10 (85) | 4 (8) | 12 (77) | |

| agree somewhat | 17 (145) | 11 (24) | 19 (118) | |

| agree | 27 (227) | 30 (64) | 26 (161) | |

| strongly agree* | 24 (199) | 48 (103) | 15 (95) | |

| Q8. Long-term use of NSAIDs in the management of chronic pain has higher risk for tissue damage, morbidity, and mortality than long-term use of opioids. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree | 4 (36) | 2 (5) | 5 (31) | |

| disagree | 17 (146) | 11 (24) | 19 (121) | |

| disagree somewhat | 20 (166) | 13 (28) | 22 (137) | |

| agree somewhat | 22 (186) | 20 (42) | 23 (142) | |

| agree | 24 (202) | 28 (59) | 22 (140) | |

| strongly agree* | 13 (110) | 26 (56) | 8 (53) | |

| Q9. There is good medical evidence that interdisciplinary treatment of back pain is effective in reducing disability, pain levels, and in returning patients to work. | .004 | |||

| strongly disagree | 1 (8) | 0 (1) | 1 (7) | |

| disagree | 1 (10) | 1 (2) | 1 (7) | |

| disagree somewhat | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | |

| agree somewhat | 11 (91) | 9 (20) | 11 (70) | |

| agree | 41 (346) | 33 (71) | 44 (272) | |

| strongly agree* | 45 (381) | 56 (120) | 41 (258) | |

| Q10. I believe that chronic pain of unknown cause should not be treated with opioids even if this is the only way to obtain pain relief. | .016 | |||

| strongly disagree* | 23 (196) | 30 (64) | 21 (130) | |

| disagree | 30 (254) | 29 (63) | 30 (190) | |

| disagree somewhat | 21 (180) | 18 (38) | 22 (139) | |

| agree somewhat | 14 (115) | 12 (26) | 14 (87) | |

| agree | 8 (70) | 5 (11) | 9 (59) | |

| strongly agree | 4 (31) | 6 (12) | 3 (19) | |

| Q11. Under federal regulations, it is not lawful to prescribe an opioid to treat pain in a patient with a diagnosed substance use disorder. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree* | 34 (291) | 46 (98) | 31 (191) | |

| disagree | 36 (301) | 36 (77) | 36 (222) | |

| disagree somewhat | 16 (132) | 7 (16) | 18 (112) | |

| agree somewhat | 6 (47) | 2 (4) | 7 (43) | |

| agree | 5 (46) | 4 (8) | 6 (38) | |

| strongly agree | 3 (29) | 5 (11) | 3 (18) | |

| Q12. I know how to obtain information about both state and federal requirements for prescribing opioids. | < .001 | |||

| strongly disagree | 7 (57) | 4 (8) | 8 (48) | |

| disagree | 13 (109) | 6 (13) | 15 (96) | |

| disagree somewhat | 13 (108) | 6 (13) | 15 (91) | |

| agree somewhat | 17 (148) | 10 (21) | 20 (125) | |

| agree | 29 (242) | 36 (78) | 26 (163) | |

| strongly agree* | 22 (182) | 38 (81) | 16 (101) |

indicates the most correct response.

Validity

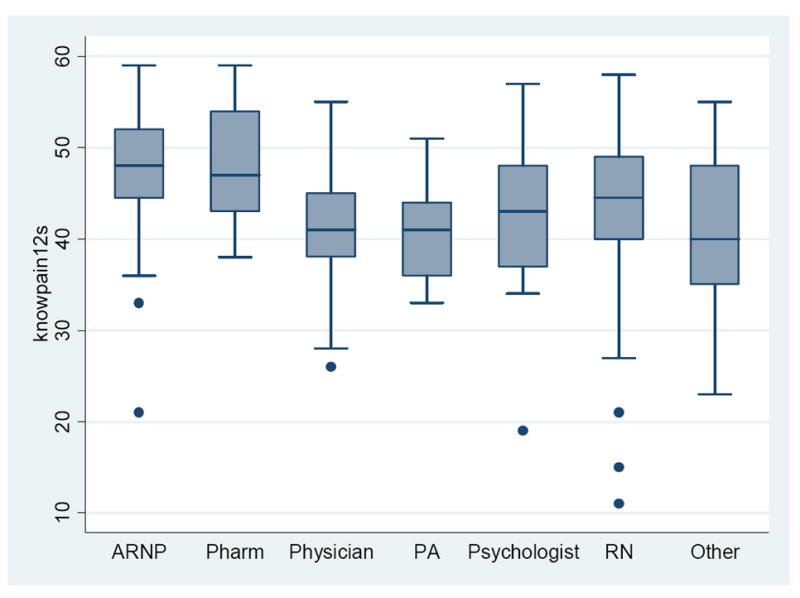

There was a significant difference (p < .0001) in the average KnowPain-12 score between pain management specialists (mean score = 48) and nonspecialists (mean score = 42). The distribution of responses to individual survey items were significantly different (p < .05) between the two groups for all items except Item 3, as mentioned above. Further, the ability of the score to distinguish between those who identified as pain specialists and those who did not was good (see Figure 1). In Figure 1, each point on the ROC curve represents a distinct cutoff score. For example, 68% of self-identifying pain specialists scored more than 45 on the KnowPain-12, while only 31% of those who did not so identify scored higher than 45. Statistically significant but likely not meaningful differences in total scores were noted by age (age < 55, mean score = 42.9; age ≥ 55, mean score = 44.4; p = .001) and for gender (male, mean score = 42.2; female, mean score = 44.1; p < .001). Pharmacists (mean score = 48) and advanced practice registered nurses (mean score = 47.6) scored highest, followed by RNs (mean score 44.3), psychologists (42.3), physicians (41.7), and physician assistants (41.1) (Figure 2)

Figure 1. Receiver-Operating Characteristic (ROC) for KnowPain-12.

Legend

A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve plots the sensitivity versus the false positive rate for different thresholds of the KnowPain-12 score. The closer the ROC is to the upper left corner, the greater the ability of the score to distinguish between the two groups.

Figure 2. Differences in KnowPain-12 Scores by Discipline.

Legend

Box Whisker plot of KnowPain-12 scores by discipline where the middle line represents the median score surrounded by boxes showing upper and lower quartiles. The lines extending vertically from the boxes indicate variability outside the upper and lower quartiles and the dots outside boxes represent outliers.

Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha for the KnowPain-12 score in this sample was 0.67. The true reliability of the KnowPain-12 is in the interval [0.67–1]. The exploratory factor analysis retained a single factor with an eigenvalue ≥ 1 (Table 4). Factor loadings of items ranged from 0.33 to 0.54.

Table 4.

Factor Loading

| Item | Factor1 |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.49 |

| 2 | 0.39 |

| 3 | 0.44 |

| 4 | 0.50 |

| 5 | 0.33 |

| 6 | 0.53 |

| 7 | 0.53 |

| 8 | 0.37 |

| 9 | 0.54 |

| 10 | 0.49 |

| 11 | 0.40 |

| 12 | 0.54 |

DISCUSSION

As stated by Harris and colleagues (10), and to our knowledge, there are no other studied pain management knowledge tests for general use that are aimed at clinicians who primarily manage chronic non-cancer pain. Our preliminary findings indicate that the KnowPain-12 (a shortened version of the KnowPain-50) shows promise as a reliable and valid multidimensional survey that can be used to differentiate knowledge and to some degree confidence of core domains of chronic non-cancer pain management.

First, pain specialists, on average, scored significantly higher than nonspecialists on the KnowPain-12, supporting the use of the total score as a measure of knowledge of chronic non-cancer pain management. This result from a contrasted-groups analysis indicates the sensitivity of the KnowPain-12 for detecting differences in chronic non-cancer pain management knowledge levels between two groups: those who self-reported to be pain specialists and those who reported themselves to be nonspecialists. The significantly higher scores on KnowPain-12 among providers who were pain specialists suggest that educational interventions providing pain specialist training could influence KnowPain-12 scores.

Second, pain specialists were more likely to select the most correct answer on 11 of the 12 survey items, indicating that the score is appropriate for assessing knowledge across all six core domains.

Despite the strong correlation between performing well on the KnowPain-12 and self-identifying as a pain specialist, the survey’s internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (0.67) was just below the threshold of what is considered acceptable (0.70). The alphas reported for the KnowPain-50 were 0.77–0.85 (10). Cronbach’s alpha increases with an increasing number of survey items (13), hence we would expect a subset of the original 50 items to have a lower alpha. Regardless, the factor analysis revealed only one dimension, suggesting that the items are internally consistent because they measure a single construct.

The use of true/false questions is generally not recommended by groups such as the National Board for Medical Examiners (NBME) because statements must be absolute without qualification, which is generally impossible in medicine. The original intent for use of a six-category Likert scoring system in the KnowPain-50 was to develop a survey tool that would be sensitive to changes in expertise and competence. However, the categories could likely measure other differences; in particular, confidence, personality, response style, and demographic differences may affect whether someone simply agrees or strongly agrees with an item. On certain items one could argue that it would be better to “agree” than “strongly agree,” since the field of pain medicine is not exact and there are many exceptions and individual differences that might account for some disagreement. Further exploration of this will be done during pre-/post-testing.

Limitations

The number and type of participants in the study was relatively large; however, it was not a randomly selected group of participants and there is limited demographic information. Thus, it may not accurately represent all the specialties and degree of experience of providers who manage patients with chronic non-cancer pain on a daily basis. The lack of involvement of certain specialties may have introduced a sample bias. The original KnowPain-50 items were designed to measure physician educational needs and may have limitations in use with other allied health providers.

One can also argue that the statement “I am a pain expert” may not truly correlate with the test taker’s pain knowledge or level of expertise. However as with the KnowPain-50, the use of a Likert-type scale rather than a dichotomous true/false scale is likely to better distinguish between a person who is more confident in a response and a person who may be guessing outright. Another reason the statement “I am a pain expert” may not be an accurate measure of the test taker’s true knowledge of pain is that it was asked after rather than before the KnowPain-12 assessment was administered. Self-identifying as a pain specialist may be influenced by confidence in one’s responses to KnowPain-12. Identifying as a pain expert could be a result, rather than a cause, of responding correctly.

There was also a wide range of participant certainty of having the right answer to the items, which raises questions about the clarity of certain items and whether there is a true correct answer. Some of the answers have supporting evidence (1–6; see Table 1 for item numbers), whereas others are based primarily on pain expert consensus (5), and some seem to be debated (8, 10) even among pain-trained health care specialists who deal with non-cancer pain on a daily basis. For example, with Item 8, it is difficult to weigh the long-term risks (e.g., cardiovascular, renal, gastrointestinal) of NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) with the risks of other options, such as long-term opioid use (which entails risk of addiction, tolerance, neuroendocrine immune effects, and psychosocial complications). Feedback related to this debate was received in Phase I. However, we chose to keep the original item wordings that had been previously validated as part of the KnowPain-50.

Because data were collected anonymously, we were unable to ask participants to complete the measure another time and thus unable to examine test-retest reliability. Future work is needed to determine this, as is testing alongside other legacy measures to determine concurrent validity and to better determine discriminative validity.

Finally, although correlated with clinical decisions and practices, the KnowPain-12 does not directly measure clinical endpoints, only clinician knowledge. These data are considered relatively low-level educational outcomes. In this case, KnowPain-12 might mislead by giving the wrong feedback to test takers about whether their knowledge is actually “pain-expert” level.

Conclusion and Next Steps

As the science of pain management advances, so too does our need to measure and improve clinicians’ knowledge of pain management and its application to practice. Caution is warranted when using previously validated KAP tests designed at a time when there was little guidance about management of chronic non-cancer pain. While the KnowPain-12 has a number of limitations, it offers a brief, easy-to-administer survey to help discriminate level and confidence of knowledge about key aspects of managing chronic non-cancer pain that are critical to safe and effective practice: namely, the development and management of a longitudinal, goal-driven treatment plan. As pain knowledge is subject to change, periodic item assessment and updates are recommended. Future research is needed to determine if this tool is sensitive to change in knowledge following educational interventions and if providers’ scores on the KnowPain-12 correlate with clinical behaviors.

Acknowledgments

funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Nursing Research grant # R01NR012450, the National Cancer Institute grant #R42 CA141875, and the National Institute of Health Pain Consortium, John D. Loeser Center of Excellence in Pain Education.

The authors wish to thank Lori James for her help administering the study.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: The authors have no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Weissman DE, Joranson DE, Hopwood MB. Wisconsin physicians’ knowledge and attitudes about opioid analgesic regulations. Wis Med J. 1991;6:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilson AM, Maurere MA, Joranson DE. State medical board members’ beliefs about pain, addiction, and diversion and abuse: a changing regulatory environment. J Pain. 2007;8(9):682–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfert MZ, Gilson AM, Dahl JL, et al. Opioid analgesics for pain control: Wisconsin physicians’ knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and prescribing practices. Pain Med. 2010;11:425–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potter M, Schafer S, Gonzalez-Mendex E, et al. Opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain: attitudes and practices of primary care physicians in the UCSF/Stanford Collaborative Research Network. J Fam Pract. 2011;50(2):145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L, Houghton M, Seefeld L, et al. Opioid therapy for chronic pain: physicians’ attitude and current practice patterns. J Opioid Manag. 2011;7(4):267–276. doi: 10.5055/jom.2011.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrell BR, McCaffery M. Duarte, CA: City of Hope; [November 5, 2012]. Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain, revised 2012. Available at: http://prc.coh.org/Knowldege%20&%20Attitude%20Survey%2010-12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janjan NA, Martin CG, Payne R, et al. Teaching cancer pain management: durability of educational effects of a role model program. Cancer. 1996;77:996–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter J, Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, et al. An interfaculty pain curriculum: lessons learned from six years experience. Pain. 2008;140:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter SR, Whitcomb ME, Weitzer WH. Multiple surveys of students and survey fatigue. New Directions for Institutional Research. 2004;12:63–73. doi: 10.1002/ir.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris JM, Fulginiti JV, Gordon PR, et al. KnowPain-50: a tool for assessing physician pain management education. Pain Med. 2007;9:542–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris JM, Elliott TE, Davis BE, et al. Educating generalist physicians about chronic pain: live experts and online education can provide durable benefits. Pain Med. 2008;9(5):555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zweig MH, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem. 1993;39(4):561–577. Review Erratum in Clin Chem 1993 39 8 1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zweig MH, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine [Erratum] Clin Chem. 1993;39(8):1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sijtsma K. On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika. 2009;74(1):107–120. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]