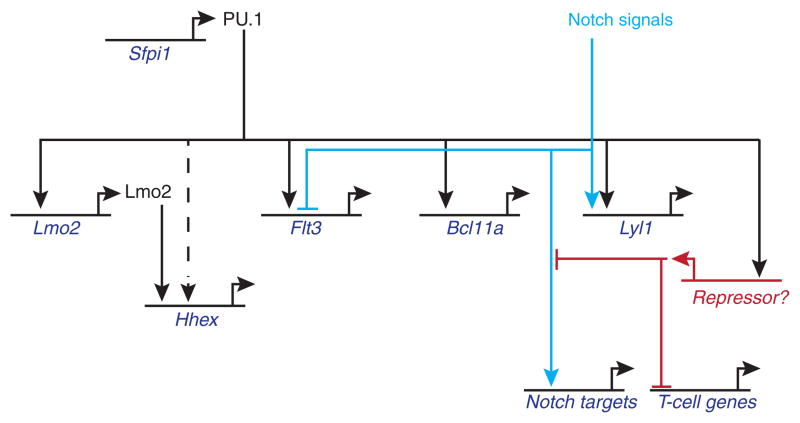

Figure 5.

A partial gene regulatory network driven by PU.1 in early T-lineage precursors. The figure summarizes representative linkages from the studies described in the text (Franco et al. 2006; Carotta et al. 2010a; Del Real and Rothenberg 2013)(A.C., S.D., S. L. Nutt, S. Carotta, and E.V.R., unpublished results). Note that combinatorial effects from PU.1 and Notch on certain targets can split the expression patterns seen in vivo (e.g. Lyl1 vs. Flt3). Additional phase 1 genes that can be activated by PU.1 in these cells include Mef2c, Meis1, and many myeloid differentiation genes; however, other genes with “phase 1” expression patterns appear to be direct negative, not positive, regulatory targets of PU.1 (not shown; A.C., S.D., S. L. Nutt, S. Carotta, and E.V.R., unpublished results). The effects depicted are those that survive Notch effects on PU.1 activity itself (Franco et al. 2006; Del Real and Rothenberg 2013). Under these conditions at least, PU.1 appears to damp expression of “T-cell genes” such as Tcf7, Ets1, Zfpm1 through an indirect mechanism, based on results with the obligate repressor dominant negative, suggesting the involvement of a PU.1-activated “Repressor X” function(s) (A.C. & E.V.R., unpublished).