Brain–neural machine interfaces (BNMIs) are systems that allow a user to control an artificial device, such as a computer cursor or a robotic limb, through imagined movements that are measured as neural activity. They provide the potential to restore mobility for those with motor deficiencies caused by stroke, spinal cord injury, or limb amputations. Such systems would have been considered a topic of science fiction a few decades ago but are now being increasingly developed in both research and industry. Workers in this area are charged with fabricating BNMIs that are safe, effective, easy to use, and affordable for clinical populations.

Because of the rapid growth of this new field, however, many issues with development, ethics, metrics, and use need to be addressed. To bring together some of the leading minds, researchers, and critics of the neural prosthetics field to discuss the current state of BNMIs, the 2013 International Workshop on Clinical Brain–Neural Machine Interface Systems was held 24–27 February 2013 in Houston, Texas [1]-[3]. Attendees included researchers from academic and government agencies; program managers from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA); as well as top industry representatives; end users of BNMI technology; medical centers and science media representatives; and selected graduate students and postdoctoral researchers (postdocs).

The conference was led by Cochairs Jose Contreras-Vidal, Ph.D., University of Houston, and Surjo Soekadar, M.D., University Hospital of Tübingen, Germany. This three-day conference embarked on an ambitious goal—to integrate input from all sectors of the BNMI field in the pursuit of developing a comprehensive roadmap for the implementation of neural interfaces and the advancement of BNMI research. The authors of this article comprise graduate students and postdoctoral researchers and acted as scribes for the conference to aid in the development and publication of the target roadmap. In this article, we present a brief summary of the clinical BNMI conference, with a focus on our perspectives, opinions, and experiences to widen the conversation regarding the future of BNMI research and encourage involvement from a diverse audience, including students, engineers, physiologists, and neuroscientists, in developing this complex roadmap.

Building a Roadmap

The conference format was a hybrid model that used a series of both plenary and “unconference”-style sessions. Before the conference, participants were asked to participate in a Web-based forum to suggest critical topics they wanted to discuss during the meeting. Each day of the conference consisted of a morning and afternoon session, starting with a plenary talk at the beginning of each session followed by open discussions in a unconference format. The topics discussed during the unconference sessions ranged from how to advance the technology of BNMI systems to the ethics of implementing BNMI devices and what should be the major next step for the field. These sessions provided a unique way for the experts to debate difficult questions, given the rapidly evolving and complex nature of the field.

Brain–neural machine interfaces are systems that allow a user to control an artificial device through imagined movements that are measured as neural activity.

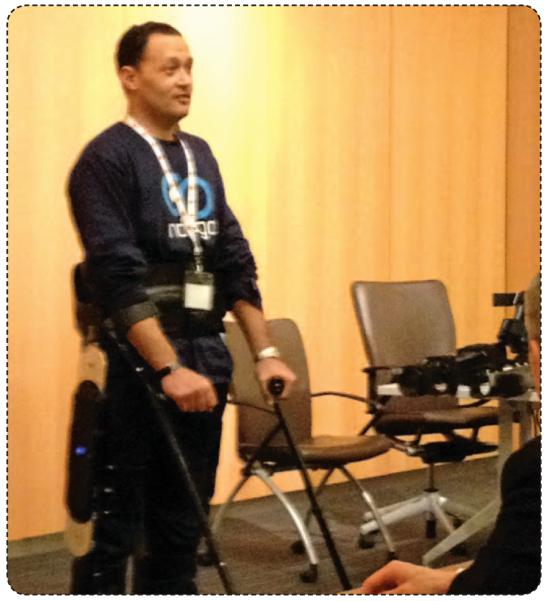

The exhibitions from industry and academic labs also demonstrated the current state of the art in clinical BNMIs, with end users testing out the products and discussing their desires and expectations from the field (Figure 1). The evenings were highlighted by social events, which provided opportunities for an informal discussion of the day’s topics and a chance for graduate students and postdocs to network with experts in the field.

FIGURE 1.

At a technology demonstration, an end user with a complete spinal cord injury answers the audience’s questions about the robotic exoskeleton that is helping him walk.

Throughout the conference, each topic of discussion reflected the diversity of the field and the different viewpoints of various stakeholders in the roadmap. It quickly became clear to us that, within the field, there are many subpopulations of research groups at different stages of development and with different needs. For example, the field of neural prosthetics for amputees is relatively well established, with reliable technologies and goals toward refining the prosthetics to make them more efficient and user friendly. On the other hand, researchers developing communication devices for locked-in patients (i.e., individuals who are awake and conscious but lack the ability to move, including moving the mouth to speak or eat, due to a neurological injury that leaves them completely paralyzed) currently need to develop a way to validate the performance of their BNMIs and to understand the neurophysiological signals they are recording. The uniqueness of each subfield within BNMIs was in some ways surprising, given the small size of the field, but it was also refreshing to see that researchers were applying BNMIs to diverse populations, all of whom were eager to use the end product.

However, this diversity brought many challenges when attempting to define one roadmap for what the entire field. Many different opinions were expressed over what the challenges researchers and developers should focus their efforts on next. While some felt they should use resources to develop new technology, such as faster processing systems or more reliable decoding algorithms, others felt that they first needed to return to basic science and develop physiological models before moving on. Andrew Schwartz, Ph.D., University of Pittsburgh, envisioned the next big win as achieving reliable and robust results from long-term studies as well as being able to actually implement this technology for home use. Similarly, Michael Boninger, M.D., University of Pittsburgh, regarded the next challenge as being able to design user-inspired and more practitioner-friendly BNMI systems.

While concurring that a big win for the field is certainly a cadre of effective device-based therapeutic interventions that are implemented clinically, Daofen Chen, Ph.D., program director at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), noted, “We still know very little about brain structure and function, and the clinical applications of BNMI provide unique opportunities to understand more about how the human brain works.” Chen believes that an even bigger win would be generating more insightful and in-depth basic science questions for further investigation. In his view, the opportunities for reverse translational research on fundamental questions about human brain circuitry and function in the area of BNMI deserve as much, if not more, attention and effort as the forward translational applications.

More answers to basic science questions are indeed essential to understanding the underlying physiology on which BNMI devices rely. However, some participants suggested that these basic scientific advances could be carried out in parallel with other efforts, such as those made to improve technology and develop metrics. The need to continue focusing on both invasive and noninvasive procedures was stressed, as participants agreed that the diverse patient population necessitates a tailor-made multifaceted approach.

In this regard, the BNMI field appears to be fragmented efforts in science, engineering, and clinical aspects of BNMI systems. This is especially relevant for procuring funding because, traditionally, funding agencies such as the NIH, NSF, and DARPA focus on these aspects separately. Chen and Kip Ludwig from NINDS assured conference attendees that this is changing and that funding agencies are now encouraged to be more collaborative and to leverage resources and synergize efforts in funding projects with strong scientific as well as health impacts. Conference Cochair Dr. Contreras-Vidal appealed to the community to continue the discussion and share their failures as well as their successes (see “Call for Participation”).

Gaining perspective

Along with other postdocs and graduate students, our role as scribes was to record the opinions of the attendees during the conference, particularly focusing on the discussion and unconference breakout sessions, and translate these records into content for the roadmap. Serving as scribes presented a unique way to experience the conference, with each scribe taking his or her own approach to capture the content.

Overall, we agreed that the scheduled talks from leading academic experts in the field were a necessity, as they provided the most current state of the art and spawned the discussion and unconference topics. In addition, the talks on funding, industry, and regulatory approaches to BNMI provided a unique perspective of the complexity of the field. Although the first few unconference sessions were a bit disorganized, we saw them become quite useful as open forums of debate on emerging and controversial topics. Generally speaking, attendees seemed to acclimate to the unconference format as the conference went on, with the liveliest discussions and the most candid conversations occurring near the end. It was exciting to see leading experts wrestle with big questions that, at more formal talks, they might gloss over. One such topic was the delicate interplay between reporting exciting progress in the field while balancing the expectations of end users, funding agencies, and the general public to match the current capabilities of the technology. This warning against creating too much hype with single-case reports of the latest advances was especially useful for us as trainees since we do not often consider dealing with the media or the public implications of our work as part of our scientific training. However, this discussion revealed the need to use the media to generate interest to garner funding for novel research while, at the same time, managing public expectations and not overstepping the ethical boundaries of what can be claimed from pilot or preliminary studies.

Another point of interest for trainees was the complexity around the discussion of metrics and how to standardize the research across the field. This is a discussion that began during the first session and continued until the end. The length and breadth of the discussion, which received input from almost everyone in attendance, demonstrated for us that issues that seem simple (e.g., how to measure the effectiveness of a BNMI) are in fact extremely complicated because of the diversity of interests and needs within the field. In some ways, it is refreshing to realize that we are entering a field that has not yet answered its own questions, one that still has room to grow, where we might be able to add influence with our own work. Seeing the gray areas within the field of BNMI debated by the field’s most respected leaders helped us see that handling ambiguity would be normal and expected and that an interdisciplinary approach is needed in any type of field work to successfully capture all perspectives.

Finally, the presence of BNMI end users at the conference was extremely helpful to us as trainees in the field. For some, this was our first chance to directly hear their opinions on the current state of the art and the issues of debate within the field. Many trainees receive input from subjects within their own studies, but having them attend the conference gave a new perspective on who are the ultimate stakeholders in the field.

Beyond the Conference Room

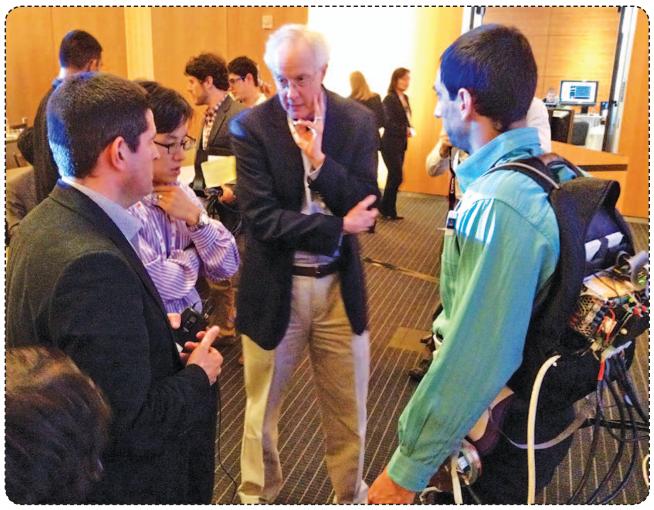

Social events were one of the best aspects of the conference because they gave attendees the opportunity to talk in a relaxed atmosphere with BNMI experts, federal agency and industry representatives, and postdocs and graduate students from other laboratories. These events were enhanced by the smaller size of the conference, which allowed for more personal interaction. We found that the attendees were more open and candid about their experiences, challenges, and concerns about the BNMI field in this setting (Figures 2-5).

FIGURE 2.

Students and professors discuss robotic exoskeletons during a break.

FIGURE 5.

Dr. Jose contreras-Vidal delivers a toast to attendees at the evening dinner where students, postdocs, industry representatives, funding agency representatives, scientists, and engineers mix and mingle.

Ludwig later noted that “bar talks,” such as those at the social events were so valuable that he replaced one of his scheduled talks with a general plea to the conference attendees to be more open and honest about their work and concerns and to be more receptive to graduate students and postdocs about their thoughts on the field. It was particularly uplifting to be acknowledged in this sense and to be assured that our questions were ones that the field had yet to answer—ones that perhaps we would be able to help answer one day with our own future work.

As scribes, we were able to sit in as “flies on the wall” and record the conversations and debates as they took place. This gave us the chance to talk to the people who spoke up and ask them to clarify their opinions, particularly during the unconference sessions when the debate was in full swing. We then presented our summaries to the whole group. This role provided a way to gain visibility in front of this audience of esteemed scientists and gave us responsibility within the process. Careerwise, it also offered opportunities to network and talk with people from industry, academia, and government agencies. Some of us were even able to set up visits and/or collaborations with labs outside of our own. For the graduate students, it was an exciting experience to meet potential postdoctoral advisors, and for postdocs, it was a chance to see how we could angle our research niche to stay on the cutting edge in the field. For all of us, it allowed us to see both the real-life pros and cons of research we had mostly just read about in journals.

While this unique experience was limited to a handful of graduate students and postdocs, we hope that future conferences will also integrate trainees in this way, as the intimate look into the state of the field let us feel that we too were responsible for the goals of the field and provided us with new insight into how our work might fit in to this bigger roadmap.

Acknowledging Diversity

The BNMI workshop in Houston began an ambitious discussion of how to create a clinical roadmap for BNMI development, involving input from a variety of perspectives, including researchers, industry representatives, program managers, clinicians, and end users. The conversation laid out a series of steps for the field to take and highlighted an emerging realization: that the diversity of potential end users and the parallel efforts by multiple groups to achieve related but different goals brings a level of complexity to unifying the field and committing it to a single clear path forward.

One major conclusion was that the informal, more detailed discussions were integral to creating a comprehensive roadmap that would include the perspectives of all groups. To that effect, the conference used small groups to spark lively and productive debate on how to best create neural interfaces that meet human needs among a diverse population of attendees, and many individuals made a commitment to continue to work together toward these goals after the meeting, including setting up their next discussions at future meetings.

By working together to alleviate current concerns—such as not having workable, field-wide metrics available—and surmount current obstacles, including lack of collaboration or limited understanding of underlying neural physiology, we will surely bring about greater new advances in the next decade, both technologically and organizationally, for the field of BNMIs than could otherwise be accomplished.

Call for Participation.

Conference Cochair Dr. Contreras-Vidal issued the following statement after the 2013 BNMI Conference:

Given the large number of patient populations and technologies involved in BMI systems, a final roadmap will likely require some iterations and the hard work of subcommittees to produce. Workshop attendees, however, agreed on some basic aspects of its framework, such as the need to put metrics, which include engineering, clinical and patient-centered factors, at the center of BMI-related research and clinical developments and the value of both invasive and noninvasive technologies for recording brain signals for BMI applications. Some of these subcommittees, such as the Clinical BMI Metrics, the Neuroethics, the Regulatory Science of BMI Systems, and the Neurofeedback Working Groups, are being formed and ask for participation by all stakeholders. If interested in volunteering in these groups or have questions about the workshop and its follow-up, please send a note to jlcontreras-vidal@uh.edu (subject line: Clinical BMI Working Groups).

FIGURE 3.

Collaborators from around the world engage in discussion during a coffee break.

FIGURE 4.

Professors, postdocs, and students help an end user with a partial spinal cord injury walk for the first time using an electroencephalography (eeG)-based robotic exoskeleton.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jose Contreras-Vidal and Dr. Surjo Soekadar for their kind invitation to allow us to serve as scribes for the conference. This conference was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Grant No. NS082045), NSF (Grant No. IIS-1313620), TIRR Memorial Hermann, the University of Houston, Rice University, and University Hospital of Tübingen, Germany. We also acknowledge the funding provided by the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Mexico, and industry sponsors.

Contributor Information

Sook-Lei Liew, The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. (liews@mail.nih.gov).

Harshavardhan Agashe, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Houston, Texas.

Nikunj Bhagat, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Houston, Texas.

Andrew Paek, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Houston, Texas.

Thomas C. Bulea, Rehabilitation Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

References

- [1].Sukel K. Roadmapping the adoption of brain-machine interfaces, The Dana Foundation [Online] 2013 Apr 15; Available: http://www.dana.org/news/features/detail.aspx?id=42098#. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Neurotech Business Reports. Brain-machine interface pioneers participate in workshop on clinical BMIs [Online] 2013 Mar; Available: http://www.neurotechreports.com/pages/workshop_clinical_brain_machine_interfaces_report.html.

- [3].2013 international workshop on clinical BMI systems [Online] Available: http://bmiconference.org/