Abstract

Primetime broadcast television provides health information and establishes norms for millions of people in the United States (Beck, 2004; Brodie, et al., 2001; Murphy & Cody, 2003; Rideout, 2008). To understand what people may be learning about reproductive and sexual health, a content analysis was conducted of storylines from the 10 most popular primetime television programs in 2009, 2010 and 2011. Variables that were measured included the frequency of reproductive and sexual health issues, the level of health information, the type of information portrayed, the gain and loss frames, the presence of stigma, the tone, and the type of role model portrayed. Eighty-seven of the 589 health storylines dealt with reproductive and sexual health, and the most common issues were pre- and post-term pregnancy complications. The majority of these storylines had a moderate or weak level of information and included specifics about treatment and symptoms but not prevention. Just over half of the issues were framed in terms of losses, meaning non-adoption of a behavior change will result in negative outcomes. Twenty-four percent of reproductive and sexual health storylines involved stigma -- usually those related to sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Most storylines were portrayed as serious and the majority of issues happened to positive role models. The implications of these portrayals for the viewing public are discussed.

Although there is a dizzying array of entertainment programming available today, it is still the case that a relatively small number of shows account for the lion's share of audience members in the United States. This is particularly true of primetime television. Primetime television is broadcast during the evening hours (8:00 P.M. to 11:00 P.M. on weeknights, 7:00 P.M. to 11:00 P.M. on Sundays) when the largest segment of the population is tuned in or recording these programs (Nielsen Wire, 2011). Primetime television usually refers to television that airs on the five broadcast networks, which are ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox, and The CW. The top 10 primetime shows are watched by 12 to 20 million viewers per week, (Associated Press, 2011), and these numbers more than triple when on-demand, re-runs and international broadcasts are included.

It is critical to understand the content of primetime television because for many it provides a crucial, often primary, source of health information and norm perceptions (Beck, 2004; Brodie, et al., 2001; Chia & Gunther, 2006; Hether et al., 2008; Murphy & Cody, 2003; Rideout, 2008). According to one survey, 26% of the public cited entertainment television as being among their top three sources of health information, and half (52%) said they consider the health information contained in these programs to be accurate (Beck, 2004; Beck & Pollard, 2001). A 2005 survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) found that 58% of primetime viewers reported learning about a health issue from TV in the past six months. Women from the survey were especially likely to report learning about health issues from primetime TV (62%) and then taking action on these issues (33%). Understanding how reproductive and sexual health issues are portrayed on primetime is of particular importance because the primary barriers to seeking more information, which include embarrassment, difficulty in accessing information, and lack of time, can be partly overcome by television (National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, 2009).

In addition to health information, primetime television also plays a central role in shaping perceptions of norms. People often use simple heuristics such as availability when deciding how likely they are to experience a particular health problem (Tversky & Kahenman, 1973) and television viewing is often a source of these probability judgments (Shrum, 2009). In fact, Shrum argues that because they are relatively accessible “media memories” may play a disproportionate role in day to day decision-making. Television in particular produces vivid memories that can be easily activated when making normative estimates about the prevalence of various behaviors, health conditions, etc. In other words, viewers may use the frequency with which a given health issue appears on television as a mental shortcut to its actual prevalence in the population. Moreover, because television viewing remains a popular pastime, it is critical to examine not only the health content to which people are exposed, but also the manner in which this content is portrayed.

One particularly important area in which the media can shape our perceptions of reality is reproductive and sexual health, which includes issues such as family planning, pregnancy, childbirth, fertility, and STIs, amongst others. These issues are almost always controversial, which makes studying their prevalence and characterization all the more imperative. Some prior studies have looked at how television can contribute to reproductive and sexual health knowledge and attitudes. For example, Brodie, et al. (2001) found that people who viewed an episode of ER in which a rape victim requests information on emergency contraception had increased awareness of the drug. They also found that knowledge about HPV (human papillomavirus) rose after viewing the episode, although it was not sustained over time. Hether, et al. (2008) found similar results for two breast cancer storylines that aired on ER and Grey's Anatomy. They found that combined exposure to these shows resulted in a greater impact on knowledge, attitudes and behaviors than exposure to either storyline individually. O'Leary, et al., (2007) found that people in Botswana who viewed a sympathetic storyline about an HIV-positive person on The Bold and the Beautiful reported significantly lower levels of HIV stigma than non-viewers. Snyder and Rouse (1995) found that exposure to movies and sitcoms dealing with AIDS resulted in increased awareness of personal risk.

Research has shown a reliance on the mass media for reproductive health information. A 2009 study of 1800 men and women aged 18-29 found that 43% of women and 25% of men cite a media source as the one they use most often to learn about reproductive health. Moreover, 62% of men and 41% women report that the media is their first choice for learning about such topics (Kaye, Suellentrop & Soup). Yet there are huge gaps in a large percentage of the general public's sexual health knowledge. A 2009 survey (National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy) of U.S. adults 18 to 29 found that one out of five never had sex education in school. Participants knew little about contraception (only 31% knew about emergency contraception and 65% knew about oral contraception) and the majority of them underestimated their likelihood of becoming pregnant or getting a female pregnant from sex.

Despite a heavy reliance on television for information there have been only a few attempts to systematically analyze the reproductive and sexual health content presented on popular programs. For example, Morris and McInerney (2010) conducted a content analysis of reality-based television shows about pregnancy and childbirth from A Baby Story and Birth Day. They looked at 123 depictions of pregnancy and childbirth and found that, contrary to a typical childbirth experience in the U.S., these shows characterized childbirth as dangerous and requiring medical intervention. The shows also overrepresented married women as the group experiencing pregnancy and childbirth. Another content analysis of health issues in local television news found that out of 3,249 health stories, none were about sexual health or reproductive health (Wang & Gantz, 2010).

In contrast to the relatively scant research examining reproductive health on television, there has been extensive research on sex on television. A content analysis of 1,276 shows from one television season found very few programs free of sexual content (Fisher, et al., 2004) and the vast majority of programs airing during primetime hours had sexual content. A Kaiser Family Foundation report (Kunkel, et al., 2005) analyzed 4,742 television programs over three years and found that 70% of shows have sexual content, with 35% depicting or simulating sexual behaviors. While sexual content is pervasive and growing, little is understood about how health issues resulting from sexual activity are portrayed.

Because health information is so prominent on television, framing is a useful tool for understanding how this information is portrayed. Framing is defined broadly by Tewksbury and Scheufele as “what unifies information into a package that can influence audiences” (2002, p. 19). Framing can be subtle or overt and “work[s] through building associations between concepts...” (p. 21). A frame does not exist entirely within a message because it has a cultural context that allows the audience to build associations. Van Gorp (2007) argues that since frames are so culturally dependent their use often goes unnoticed. He points out that the persistent nature of frames means that they change little over time. Furthermore he argues that the purpose of frame analysis is to assess “the impact of the implicitly present cultural phenomena conveyed... as a whole and to relate them to the dynamic processes in which social reality is constructed” (p. 73).

The current study examines how reproductive and sexual health issues are framed on primetime television. The present analysis of three seasons of popular primetime programming will reveal not only which reproductive health issues are portrayed but, perhaps more importantly, how they are portrayed. To understand which issues are portrayed we address the following research question:

RQ1: Which reproductive and sexual health issues are portrayed most frequently in primetime television?

Since over half of primetime viewers trust information on television to be true, it is also necessary to assess the informational content. To understand what people may be learning from primetime, we identify the level of information of the storylines. We also analyze the specific type of information portrayed in the storyline, including prevention, risk factors, symptoms, complications, treatment, prognosis and diagnosis. To understand the level and type of information we address the following two research questions:

RQ2: What is the level of information in reproductive and sexual health storylines on primetime television?

RQ3: What type of health information (prevention, risk factors, symptoms, complications, treatment, prognosis, diagnosis) is portrayed in reproductive and sexual health storylines?

In addition to measuring the frequency and informational content of these sexual and reproductive health storylines we also assess how they are framed. Messages containing risk, such as those about health issues, can either be framed such that adoption of a behavior will result in positive outcomes (gains) or that non-adoption of a behavior will result in negative outcomes (losses). This is particularly important given that gain-framed messages have been shown to be more effective for prevention behaviors and loss-framed messages are more effective for detection behaviors (Rothman et al., 1993) although a recent study by Nan (2012) found that the effectiveness of gain and loss frames was dependent on individual traits (whether a person was avoidance-oriented or approach-oriented). To assess relative frequency of gain and loss frames on primetime we pose the following question:

RQ4: Are reproductive and sexual health issues more often framed in terms of gains or losses on primetime television?

In addition, this analysis also examines whether reproductive and sexual health issues are portrayed as being stigmatized. Therefore, we address the following research question:

RQ5: Are reproductive and sexual health issues portrayed as stigmatized?

We also examine whether the tone is comic, casual, or serious. Some research has suggested that comic portrayals of health issues may reduce perceptions of the severity of the issue. For instance, Moyer-Gusé, Mahood, & Brookes (2011) found that when pregnancy is portrayed on television in a humorous tone viewers are more likely to engage in unprotected sex than when it is portrayed in a serious tone. Other research has shown that viewing humorous portrayals of delivery may encourage more open discussion about pregnancy anxieties (Grady & Glazer, 1994). We address the following question:

RQ6: Is the tone of reproductive and sexual health storylines more likely to be comic, casual, or serious?

Finally, we examine whether the character experiencing the issue is a positive, negative, or transitional role model. Past research has shown that the type of role model associated with a health issue has differing persuasive effects depending on how they are portrayed (Singhal & Rogers, 1999; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Our final research question addresses this issue: RQ7: Is the character experiencing the health issue more often portrayed as a positive, negative, or transitional role model?

Method

Sample

The Hollywood, Health & Society TV Monitoring project, a program of the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism's Norman Lear Center, has tracked and coded health-related content from the spring season of the most popular primetime broadcast shows, as defined by Nielsen ratings since 2004. For the current analysis, researchers coded the health content of the top 10 scripted primetime shows, including dramas and comedies, for Nielsen's General Audience, African American Audience and Latino Audience, ages 18-49, airing in 2009, 2010 and 2011. Latino and African American audiences are of particular importance because they have lower access to healthcare and report being in poorer health (Centers for Disease Control, 2009). African Americans are also the highest consumers of television, and 86% of Latino audiences watch English language television, regardless of the language spoken at home (Nielsen Media Research, 2010). Although the three audience categories have some overlap in the top ten most watched shows, shows and storylines were only included once in the sample.

Coders initially coded the prominence of all health storylines, ranging from visual cue and brief mention, to dialogue, and minor or major storyline. The unit of analysis for this research was the health storyline, and only dialogue-level storylines, minor storylines, and major storylines about health were included since these are more detailed and contain more information than brief mentions and visual cues. A dialogue was a conversation that took place between characters. If the conversation took place in two or three scenes and was secondary in importance to the plot it was then considered a minor storyline. If it took place in more than three scenes and was the primary focus of the episode it was considered a major storyline. After coding the prominence of each storyline coders re-watched the episode as many times as needed to complete the coding of each storyline.

Out of 2,342 storylines coded over three years, a total of 589 (25%) major, minor and dialogue-level health storylines were found in the sample. Of these, 87 (14%) were about reproductive and sexual health. Within the final sample of 87 storylines, 45% were minor storylines, 32% were dialogues, and 23% were major storylines. Of the 54 television shows in the larger sample, 17 had storylines about reproductive or sexual health. These included shows such as Law and Order: SVU, Grey's Anatomy, The Office, Two and Half Men, Private Practice, and Desperate Housewives. Eight of the shows were dramas and nine were comedies.

Coder Training and Reliability

Fifteen coders were employed for the study and were compensated for their time. Coders received at least three full days of training and most were Master's degree students in public health. Coders practiced coding primetime shows that were not in the final sample until coding discrepancies were resolved and agreement was high, which took four rounds of hour-long episodes. Since the final sample was small, all 87 of the storylines underwent reliability coding by at least two coders. Reliability was found to be moderate to high for health issue (Kappa = .715, p = .001), level of information (Kappa = .894, p < .001), type of information portrayed (Kappa = .889, p < .001), message framing (Kappa = .808, p < .001), stigma (Kappa = .722, I < .001), tone (Kappa = .783, p < .001), and role model (Kappa = .841, p < .001).

Instrument

The Hollywood, Health & Society TV Monitoring Project has two code sheets. The general code sheet is used to gather information about the shows themselves and which health topics appear in them. The specific code sheet is used only for episodes with dialogues and major or minor storylines to get more detailed information about each particular storyline. The current study relied exclusively upon the storyline coding scheme found on the specific code sheet.

Variables Coded and Analyzed

Health issue

The health issues in this analysis are related to sex and reproduction, and include pre-/post-term pregnancy complications, family planning (including birth control or storylines dealing with choosing to have children), female genital mutilation, circumcision, fistula, infertility, labor and delivery, pre-/post-natal care (including infant feeding), reproductive tract infections, abortion, miscarriage, unplanned pregnancy, STIs other than HIV/AIDS, and HIV/AIDS.

Level of information

Informational levels were defined as either strong, (meaning a very clear and accurate portrayal of the health issue), moderate (somewhat clear and accurate portrayal), weak, (meaning vague, brief, or incomplete portrayal), or no informational content. Examples of informational content include a doctor describing how a procedure works, or friends talking about the transmission and symptoms of an STI.

Type of health information

The type of information was coded as prevention (how an issue can be prevented or screened for), risk factors (any variables associated with increased risk), symptoms (signs that a health issue is occurring), diagnosis (identification of the issue, usually by a medical professional), treatment (course of action), complications (including side-effects), and prognosis (probable outcome). These categories were not mutually exclusive since some health storylines portray multiple types of health information.

Message framing

The framing of messages was defined by one of three categories: either gain-framed, meaning good things will happen as a result of behavior change, loss-framed, meaning bad things will happen as a result of no behavior change, or as neither gain- nor loss-framed.

Stigma

Issues were coded as stigmatized if there was any mark of shame or disgrace for a health issue. An example would be expressing humiliation about having an STI.

Tone

Tone was coded as either comic (portrayed in a joking or sarcastic manner), casual (portrayed in passing with no major consequential effects), or serious (portrayed as having serious implications). These categories were mutually exclusive.

Role model

Lastly, we coded whether the health issue involved a character who was a positive role model (a character who is favorably depicted and models a healthy attitude or behavior), negative role model (a character who is unfavorably depicted and models an unhealthy attitude or behavior), or transitional role model (a character who shifts over the course of the storyline from modeling an unhealthy behavior or attitude to a healthy one).

Results

The following findings are from analyses of the 87 storylines that aired on the top 10 primetime television shows for 2009, 2010 and 2011 for General, Latino and African American adult audiences, representing 81.5 hours of television. See Table 1 for a summary of findings.

Table 1.

Summary of Variables Analyzed in Reproductive and Sexual Health Storylines (N = 87)

| Variable | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of Health Issue | ||

| Pre-/Post-Term Complications | 35 | 30 |

| Labor and Delivery | 15 | 13 |

| Family Planning | 14 | 12 |

| Infertility | 9 | 8 |

| STIs other than HIV/AIDS | 8 | 7 |

| Unplanned Pregnancy | 7 | 6 |

| Pre-/Post-Natal Care | 7 | 6 |

| All Others | 5 | 5 |

| Informational Value | ||

| Moderate | 43 | 37 |

| Weak | 39 | 34 |

| No Informational Value | 12 | 11 |

| Strong | 6 | 5 |

| Type of Information | ||

| Treatment | 60 | 52 |

| Symptoms | 48 | 42 |

| Diagnosis | 43 | 37 |

| Complications | 30 | 26 |

| Risk Factors | 26 | 23 |

| Prognosis | 20 | 17 |

| Preventions | 15 | 13 |

| Message Framing | ||

| Loss-Framed | 55 | 48 |

| Gain-Framed | 35 | 30 |

| Neither Loss- Nor Gain-Framed | 10 | 9 |

| Stigma | ||

| No Stigma Portrayed | 76 | 66 |

| Stigma Portrayed | 24 | 21 |

| Tone | ||

| Serious | 86 | 75 |

| Casual | 9 | 8 |

| Comic | 5 | 4 |

| Role Model | ||

| Positive Role Model | 68 | 59 |

| Negative Role Model | 18 | 16 |

| Transitional Role Model | 14 | 12 |

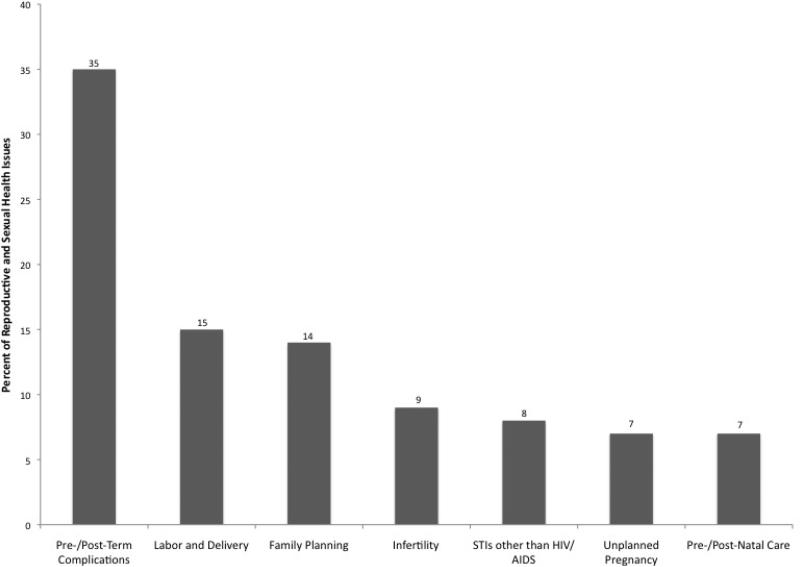

RQ1: Frequency of Health Issues

A one-way chi-square analysis revealed significant differences between health issues portrayed (X2(8) = 58.97, p < .001). The most common issue portrayed was pre-/post-term complications (35%). These included issues such as pre-eclampsia, surgery during pregnancy, and premature birth. Pre- and post-term complications differed significantly (X2(1) = 31.58, p < .001) from the next most common issue, which was labor and delivery (15%) followed by family planning (14%) such as contraception, infertility (9%), STIs other than HIV/AIDS (8%), unplanned pregnancy (7%), and pre- and post-natal care (7%). Other issues were mentioned only once or twice, including AIDS, genital mutilation, circumcision, and abortion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reproductive and Sexual Health Issues Portrayed on Primetime

RQ2: Level of Information

The majority of storylines had a moderate level of information (43%), followed by a weak or vague level of information (39%), no informational value (12%) and a strong level of information (6%). A one-way chi-square analysis revealed statistically significant differences between levels of health information (X2(3) = 34.84, p < .001). Subsequent pair-wise comparisons revealed significant difference between all categories, except weak and moderate content (X2(1) = .06, p = .81).

RQ3: Type of Health Information

All the possible types of information in the coding scheme were portrayed. Many storylines included information on treatment (60%), symptoms (48%), and diagnosis (43%). Fewer included information on complications (30%), risk factors (26%), prognosis (20%), and prevention (15%). Since categories were not mutually exclusive we also looked at how many types of information were portrayed in each storyline. The majority featured one or two types of information (39%), followed by three or four types of information (27%), no type of information (18%), and five or six types of information (16%), which all differed significantly (X2(3) = 11.25, p = .01). A pair-wise comparison revealed a significant difference between those featuring one or two types of information and two or three types of information. Those with no type of information and those with five or six types of information could not be calculated due to the small number of cases in these categories.

RQ4: Message Framing

Health behaviors were most often framed in terms of losses (e.g., bad things will happen as a result of no behavior change) at 55%. An example of a loss-framed storyline is one where not having a type of surgery will result in an unsafe delivery of a baby.

However, a substantial number of storylines -- 35% -- were framed in terms of gains (e.g., good things will happen as a result of behavior change) and the remaining 10% had neither a gain nor loss frame. Differences between frames were significant (X2(2) = 26.28, p < .001), and pair-wise comparisons demonstrated that there were significantly more loss-frames than gain-frames (X2(1) = 4.15, p < .04)

RQ5: Presence of Stigma

The majority of reproductive and sexual health storylines were not portrayed as stigmatized (76%), and the difference was significant (X2(1) = 23.28, p < .001). Of the 24% (n = 21) that were stigmatized, nine were storylines about STIs including AIDS, four were about unplanned pregnancies, and the remainder were about family planning, abortion, and breast-feeding.

RQ6: Comic, Casual, or Serious Tone

The vast majority of storylines were portrayed in a serious tone (86%), and the difference between tones was significant (X2(2) = 109.72, p < .001). A casual tone occurred in 9% of storylines, and a comic tone occurred in 5% of storylines, and there was no significant difference between the two (X2(1) = 1.33, p = .25). Of the four storylines portrayed in a comic tone two were about STIs, one was about a person going into labor unexpectedly, and one was about the high cost of post-natal care. Casual storylines were about sore breasts, trouble breastfeeding, infertility, ultrasound, and disagreement about having a child.

RQ7: Positive, Negative, or Transitional Role Model

The majority of characters experiencing the health issue were positive role models (68%), followed by negative role models (18%) and transitional role models (14%). Coders had the option to code characters as neutral, but did not identify any neutral characters experiencing the health issues in these storylines. One-way chi-square analyses revealed a significant difference between the three categories (X2(2) = 46.83, p < .001), but a follow-up pair-wise comparison showed no significant difference between negative and transitional role models (X2(1) = .571, p = .45). Of those storylines with negative role models, seven dealt with unplanned pregnancy or family planning specifically for teens, and four dealt with STIs. Storylines with transitional role models had no consistent patterns, and examples include a teen who decides to be abstinent, and a woman whose pre-natal worries go away.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine portrayals of reproductive and sexual health on popular primetime television programs. To do so, we content analyzed a sample of 589 major and minor storylines across the ten most popular programs for General, African American and Latino audiences over three consecutive spring seasons. This yielded a final sample of 87 separate storylines that dealt with reproductive or sexual health.

Our analysis showed that pre- and post-term complications and labor and delivery accounted for the majority of issues. These issues lend themselves to dramatic storytelling more so than other topics such as family planning and pre- and post-natal care. Interestingly, issues that are more likely to affect viewers in real life such as STIs and unplanned pregnancies were far less common in primetime. This raises the question -- which is beyond the scope of our data -- of whether the scarcity of depictions of such common problems leads viewers to underestimate their own risk.

We also found that much of the informational content was moderate (43%), a somewhat surprising finding given that the television industry is not required to provide primetime audiences with educational or informational content. However, 39% of storylines had weak or vague informational content. Having this many issues portrayed either inaccurately or insufficiently may result in audiences being misinformed. Only 6% of the sample had a strong level of information. An analysis of health on primetime between 2004 and 2006 (Murphy, Hether, & Rideout, 2008) found that 28-35% of all health storylines had strong informational value, which may suggest that reproductive and sexual health issues are presented with strong informational content less often than other health issues.

Our findings indicate that viewers are exposed to a fair amount of information about treatment, symptoms, and diagnosis, but information regarding how to prevent health issues appears to be scarce. Again, this is likely due to the fact that symptoms and diagnoses lend themselves more to dramatic storytelling than risk factors and prevention, although some health issues may not be preventable, like certain pregnancy complications. Almost half of the storylines included three or more types of information, although nearly a fifth of storylines had none. More research is needed to understand how viewers respond when certain types of information are portrayed together, and how each type of information affects attitudes and behaviors.

While not all issues equally lend themselves to gain or loss frames, our analysis revealed that just over half of the portrayals were loss-framed and that these occurred significantly more often than gain-framed messages. This type of framing has considerable implications for how people perceive behavior change and risk. On the negative side, preventing a health problem is far more desirable than detecting or treating it. Thus, ideally more prevention would be portrayed in primetime television. However, one potentially positive aspect of the findings is that loss-framed messages may be more persuasive for detection behaviors (Rothman, et al., 1993) such as symptoms and diagnoses, which occurred in almost half of the storylines in our sample, than prevention behaviors which were relatively rare. While intriguing, more research is needed to understand the effect of message framing specific to reproductive and sexual health issues.

For the question of stigmatization, findings indicated that most of these health issues were not stigmatized. This was somewhat surprising given the intimate and controversial nature of sexual and reproductive health issues. However, those that were stigmatized tended to be related to STIs including AIDS. This finding suggests that while issues dealing with pregnancy complications, labor, or delivery are not usually stigmatized, STIs are often portrayed as a source of shame and embarrassment. Along those lines, most reproductive and sexual health storylines were conveyed in a serious tone. The few storylines that were portrayed as comic or casual dealt with issues like STIs and breastfeeding, rather than labor, delivery, and pregnancy complications. The high number of storylines with a serious tone suggests that reproductive health topics are usually portrayed as dramatic, even life-threatening. In fact, although the sample was evenly split between comedic and dramatic shows, the majority of sexual and reproductive health storylines came from dramas (85%). Although we would not expect pregnancy complications to be dealt with casually, these findings highlight that most reproductive and sexual health issues are considered grave, while only certain issues are discussed flippantly.

Most of the health issues in our analysis depicted positive role models, or people who were portrayed favorably. Many of those that depicted negative role models dealt with teen pregnancy or family planning, which may suggest negative views towards teen sexuality. This finding is notable because past research has shown that positive role models are more likely to enhance persuasive effects, and negative role models are more likely to be persuasive when the character experiences negative outcomes (Singhal & Rogers, 1999). There was no consistent pattern for health issues that involved transitional role models.

These findings have important implications for other aspects of health communication research as well. Only about a quarter of reproductive and sexual health storylines were major storylines, which is significant in light of what we know about the role transportation plays in changing beliefs (Green & Brock, 2000; Green, Brock & Kaufman, 2004). When individuals are highly transported by a storyline their beliefs tend to be congruent with those in the storyline. Understanding if and how transportation takes place during only minor or dialogue-level storylines could expand our knowledge of the role of narrative in changing beliefs.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that the sample does not include unscripted reality programming, which is common on primetime television. Future researchers should consider analyzing the content of reality programming, especially shows with a health-oriented angle, such as Biggest Loser and Celebrity Rehab. These shows are of interest because they may address health issues differently than fictional shows, perhaps calling upon experts and testimonies.

Another limitation is the relatively small sample size. The fact that only 14% of the larger sample had storylines about sexual and reproductive health speaks to the scarcity of this issue on TV. Nonetheless a larger sample size, perhaps over several years, would allow for more comparisons between issues.

Another limitation is that primetime television, while having a large viewership, is targeted primarily at English-speaking populations. Moreover, we recognize that mainstream media is just one part of a much larger story about how information is distributed and norms are established. While it is still useful to monitor how values and norms are expressed in primetime television it must be remembered that these values and norms may be augmented or attenuated by other sources of information such as interpersonal communication, other media, etc.

Conclusion

This content analysis sheds light on how these highly personal issues are portrayed to millions domestically and billions internationally. On the positive side, audiences may be exposed to a substantial amount of health content. On the negative side, many crucial health issues are underrepresented, and primetime content may contain more information on how to treat a disease than how to prevent it. Given the attention and accuracy the viewing public ascribes to primetime television content, health practitioners and scholars would be wise to take note of what health information is being conveyed, what is not being conveyed, and the potential effects of these portrayals.

Our analysis also shows that reproductive and sexual health issues, while scarce, are framed as serious and dramatic, though not necessarily stigmatized. Ordinary or routine reproductive health issues do not receive as much attention. Though there were few cases of STIs on primetime, our analysis suggests that these non-pregnancy issues are dealt with quite differently, often with stigma, treated casually or humorously, and happening to negative role models. People experiencing pregnancy and delivery issues are typically positive role models, as long as they are not teens.

This study may be a useful starting point for research that would include a more ecological view of how health information and social norms are spread, as well as a better understanding of how audiences actually perceive these messages. The results of this paper are not meant to suggest that is the responsibility of television producers and writers to provide accurate health information that reflects the information needs of the audience. Instead, we provide an overview of what is on television to understand which issues are portrayed and how they are being portrayed. While primetime television does not tell the whole story of how mediated communication addresses reproductive health it is nevertheless a crucial area for examining these issues and drawing attention to the potential effects of these portrayals.

Contributor Information

Katrina L. Pariera, Department of Communication, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, University of Southern California

Heather J. Hether, Department of Communication, University of the Pacific

Sheila T. Murphy, Department of Communication, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, University of Southern California

Sandra de Castro Buffington, Hollywood, Health & Society, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism's Norman Lear Center, University of Southern California.

Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, Department of Preventive Medicine and Sociology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California.

References

- Associated Press A list of the top 20 prime-time programs in the Nielsen ratings for Oct. 17-23. The Washington Post. 2011 Oct 25; Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/a-list-of-the-top-20-prime-time-programs-inthe-nielsen-ratings-for-oct-17-23/2011/10/25/gIQAbUT5FM_story.html.

- Beck V. Working with daytime and primetime television shows in the United States to promote health. In: Singhal A, Cody MJ, Rogers EM, Sabido M, editors. Entertainment-education and social change: History, research, and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Beck V, Pollard WE. How do regular viewers of primetime entertainment television shows respond to health information in the shows? Paper presented at the American Public Health Association; Atlanta, GA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie M, Foehr U, Rideout V, Baer N, Miller C, Flournoy R. Communicating health information through the entertainment media: a study of the television drama ER lends support to the notion that Americans pick up information while being entertained. Health Affairs. 2001;20:192–199. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [November 12, 2011];TV Drama/Comedy Viewers and Health Information 2005 Porter Novelli HealthStyles Survey. 2005 from http://www.cdc.gov/healthmarketing/entertainment_education/healthstyles_survey.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Summary Health Statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, Vital and Health Statistics. 2009. Series 10(Number 249), December, 2010.

- Chia SC, Gunther AC. How media contribute to misperceptions of social norms about sex. Mass Communication & Society. 2006;9:301–320. doi:10.1207/s15327825mcs0903_3. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DA, Hill DL, Grube JW, Gruber EL. Sex on American television: An analysis across program genres and network types. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2004;48:529–553. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4804_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady K, Glazer G. Humor in prenatal education: From egg to eggplant. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 1994;3:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, Brock TC. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:701–721. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Brock T, Kaufman G. Understanding media enjoyment: The role of transportation into narrative worlds. Communication Theory. 2004;14:311–327. doi:10.1093/ct/14.4.311. [Google Scholar]

- Hether HJ, Huang G, Beck V, Murphy ST, Valente T. Entertainment-education in a media-saturated environment: Examining the impact of single and multiple exposures to breast cancer storylines on two popular medical dramas. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13:808–823. doi: 10.1080/10810730802487471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye K, Suellentrop K, Sloup C. [September 2, 2011];The fog zone: How misperceptions, magical thinking, and ambivalence put young adults at risk for unplanned pregnancy. 2009 from http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/reports.aspx#20.

- Kunkel D, Eyal K, Finnerty K, Biely E, Donnerstein E. [September 4, 2011];Sex on TV 4: A Kaiser Family Foundation Report. 2005 from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/7398.cfm.

- Morris T, McInerney K. Media representations of pregnancy and childbirth: An analysis of reality television programs in the united states. Birth Issues in Perinatal Care. 2010;37:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Gusé E, Mahood C, Brookes S. Entertainment-education in the context of humor: Effects on safer sex intentions and risk perceptions. Health Communication. 2011;26(8):765–774. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.566832. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.566832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST, Cody MJ. [September 1, 2011];Summary report: Developing a research agenda for entertainment education and multicultural audiences. Printed by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. 2003 from www.learcenter.org.

- Murphy ST, Hether HJ, Rideout V. [September 2, 2011];How healthy is primetime?: An analysis of health content in popular prime time television programs. 2008 from www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/7764.pdf.

- Nan X. Communicating to young adults about HPV vaccination: Consideration of message framing, motivation, and gender. Health Communication. 2012;27:10–18. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.567447. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.567447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy [September 2, 2011];Magic thinking: Young adults’ attitudes and beliefs about sex, contraception, and unplanned pregnancy. Results from a public opinion survey. 2009 from http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/reports.aspx#20.

- Nielsen Media Research [October 1, 2011];A Snapshot of Hispanic Media Usage in the United States. 2010 from http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/online_mobile/state-of-the-media-hispanic-media-use/

- Nielsen Wire [September 29, 2011];10 years of primetime: The rise of reality and sports programming. 2011 Sep 21; from http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/media_entertainment/10-years-of-primetime-the-rise-of-reality-and-sports-programming/

- O'Leary A, Kennedy MG, Pappas-DeLuca K, Nkete M, Beck V, Galavotti C. Association between exposure to an HIV story line in The Bold and The Beautiful and HIV-related stigma in Botswana. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:209–217. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V. [September 3, 2011];Television as health educator: A case study of Grey's Anatomy. A Kaiser Family Foundation report. 2008 from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/7803.cfm.

- Rothman AJ, Salovey P, Antone C, Keough K, Martin CD. The influence of message framing on intentions to perform health behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1993;29:408–433. [Google Scholar]

- Shrum LJ. Media Consumption and Perceptions of Social Reality. In: Bryant J, Oliver M, editors. Media Effects: Advances in theory and Research. Routledge; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, Rogers EM. Entertainment-Education: A Communication Strategy for Social Change. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Rouner D. Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory. 2002;12:173–191. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LB, Rouse RA. The media can have more than an impersonal impact: The case of aids risk perceptions and behavior. Health Communication. 1995;7:125–145. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc0702_3. [Google Scholar]

- Tewksbury D, Scheufele DA. News framing theory and research. In: Bryant J, Oliver M, editors. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Routledge; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology. 1973;5:207–232. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(73)90033-9. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gorp B. The constructionist approach to framing: Bringing culture back in. Journal of Communication. 2007;57:60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Gantz W. Health content in local television news: A current appraisal. Health Communication. 2010;25:230–237. doi: 10.1080/10410231003698903. doi:10.1080/10410231003698903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]