Abstract

The fixation of inorganic carbon has been documented in all three domains of life and results in the biosynthesis of diverse organic compounds that support heterotrophic organisms. The primary aim of this study was to assess carbon dioxide fixation in high-temperature Fe(III)-oxide mat communities and in pure cultures of a dominant Fe(II)-oxidizing organism (Metallosphaera yellowstonensis strain MK1) originally isolated from these environments. Protein-encoding genes of the complete 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate (3-HP/4-HB) carbon dioxide fixation pathway were identified in M. yellowstonensis strain MK1. Highly similar M. yellowstonensis genes for this pathway were identified in metagenomes of replicate Fe(III)-oxide mats, as were genes for the reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle from Hydrogenobaculum spp. (Aquificales). Stable-isotope (13CO2) labeling demonstrated CO2 fixation by M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 and in ex situ assays containing live Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats. The results showed that strain MK1 fixes CO2 with a fractionation factor of ∼2.5‰. Analysis of the 13C composition of dissolved inorganic C (DIC), dissolved organic C (DOC), landscape C, and microbial mat C showed that mat C is from both DIC and non-DIC sources. An isotopic mixing model showed that biomass C contains a minimum of 42% C of DIC origin, depending on the fraction of landscape C that is present. The significance of DIC as a major carbon source for Fe(III)-oxide mat communities provides a foundation for examining microbial interactions that are dependent on the activity of autotrophic organisms (i.e., Hydrogenobaculum and Metallosphaera spp.) in simplified natural communities.

INTRODUCTION

The fixation of inorganic carbon (i.e., carbon dioxide [CO2]) is an important metabolic process in all three domains of life and can initiate trophic cascades that support ecosystem food webs. Photoautotrophs incorporate CO2 by using the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle and have long been recognized as significant contributors to the global carbon cycle. The role of archaeal carbon dioxide fixation in microbial communities, however, is not well studied. Until recently, the contribution of chemoautotrophs (specifically Archaea) to CO2 fixation has been underappreciated on a global scale, yet the contribution of chemoautotrophic prokaryotes to system productivity is important in numerous habitats. For example, members of the Thaumarchaeota (previously referred to as “marine Crenarchaeota”) represent up to 40% of deep-ocean “bacterioplankton” (1) and have now been implicated as major contributors to global carbon and nitrogen cycling (2–4). Consequently, the discovery of new CO2 fixation pathways and the identification of specific populations that contribute to the fixation of CO2 in natural habitats provide a foundation for understanding how microbial systems contribute to global carbon cycling.

Numerous archaea are capable of CO2 fixation via different mechanisms (5–8). The 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate (3-HP/4-HB) and dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate (DC/4-HB) pathways for CO2 fixation have been identified recently in different members of the Crenarchaeota (9, 10). Both cycles regenerate acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) from succinyl-CoA via seven enzyme-catalyzed reactions, including a dehydration reaction (4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA to crotonyl-CoA), which is catalyzed by 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase (4HCD). Consequently, the 4HCD gene (encoding the type 1 4HCD protein) is a marker gene for both pathways. The 3-HP/4-HB pathway has been identified in members of marine and soil Thaumarchaeota (1, 11), and the 4HCD gene was found at abundances similar to those of RubisCO, the marker gene for the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle, in the Global Ocean Survey (GOS) (9, 12). Therefore, it was suggested that abundant mesophilic autotrophic Thaumarchaeota in the open ocean utilize the 3-HP/4-HB cycle (or a variant thereof) to fix substantial quantities of CO2 (9, 10, 13).

Iron oxide microbial mats from acidic (pH ∼3) geothermal outflow channels of Yellowstone National Park (YNP) contain chemolithotrophic microorganisms responsible for the oxidation of Fe(II) and the biomineralization of Fe(III)-oxides (14–17). These microbial communities represent a consortium of numerous archaea, including several crenarchaeal populations (orders Sulfolobales, Desulfurococcales, and Thermoproteales) and representatives of the candidate phylum Geoarchaeota (18–20), as well as acidophilic bacteria from the order Aquificales. Hydrogenobaculum spp. are the dominant bacterial population(s) present in high-temperature (i.e., >65°C) acidic Fe mats, and these organisms fix CO2 through a modified version of the reductive tricarboxylic acid (r-TCA) cycle that cleaves citrate via citryl-CoA lyase and citryl-CoA synthetase (21, 22). Mature Fe(III)-oxide mats of a 0.5- to 1-cm thickness contain relatively low levels of Hydrogenobaculum-like organisms (2 to 10% of random shotgun sequences). However, these bacteria are important colonizers during the formation of Fe mats (23) and are often found in communities that contain Fe(II)-oxidizing members of the order Sulfolobales, such as Metallosphaera yellowstonensis (17).

M. yellowstonensis-like populations (>98% nucleotide identity to M. yellowstonensis strain MK1) represent 10 to 20% of random metagenome sequences from amorphous Fe(III)-oxide mats in YNP, over a temperature range of 60°C to 75°C and a pH range of 2.9 to 3.5 (n = 8 metagenome samples) (19, 24, 25). Recent work has shown that Metallosphaera sedula, as well as other members of the Sulfolobales, fixes CO2 via the 3-HP/4-HB pathway (9, 26), and initial culture experiments with M. yellowstonensis in the presence of CO2 and yeast extract (YE) suggested facultative autotrophy (17). However, the fixation of CO2 was neither conclusively demonstrated in pure culture nor shown in environmental samples. Consequently, the objectives of the current study were to (i) identify all 15 candidate genes of the 3-HP/4-HB carbon dioxide fixation pathway in M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 and in de novo genome assemblies from acidothermophilic Fe(III)-oxide microbial mat communities in YNP, (ii) utilize stable-isotope (13CO2) labeling to obtain direct evidence of CO2 fixation by M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 and live Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats, and (iii) determine the extent of CO2 fixation in situ by using stable-isotope analysis of different carbon pools within replicate Fe(II)-oxidizing geothermal channels. Results from this study establish that high-temperature Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats contain significant fractions of carbon derived from dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and that M. yellowstonensis-like organisms present in these systems fix CO2 via the 3-HP/4-HB pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Field sites.

Three different acid-sulfate-chloride geothermal springs in the One Hundred Springs Plain of Norris Geyser Basin, YNP, were sampled for this study, including One Hundred Springs Plain Spring (“OSP Spring”) (44°43′58.953″N, 110°42′32.374″W), “Grendel Spring” (44°43′58.0074″N, 110°42′34.4016″W), and “Beowulf Spring” (44°43′53.4″N, 110°42′40.9″W) (these are not official YNP names; thus, coordinates are provided). The source water temperature of all springs ranged from ∼80°C to 84°C. Microbial mat samples (3 to 5 g [wet weight]) for the ex situ CO2 uptake experiments as well as for direct isotope ratio measurements were excised from the Fe-oxide mat, approximately 2 to 3 m from the source, where the mat temperatures range from 65°C to 72°C. The sampling sites were designated OSP site B (OSP_B), GRN_D, and BE_D. Replicate metagenomes of Fe(III)-oxide mats from OSP Spring and Beowulf Spring were obtained previously (25, 27) and analyzed in this study for all genes important for a complete 3-HP/4-HB cycle. Replicate water samples from 2010 to 2013 were collected and analyzed for both the carbon concentration and isotope content (δ13C) of dissolved (0.2-μm-filtered) and total organic and inorganic carbon (Colorado Plateau Stable Isotope Laboratory, Flagstaff, AZ).

Genome analysis.

All genes involved in the 3-HP/4-HB cycle, including the key marker 4HCD gene (type I) (9) and the biotin carboxylase subunit of the bifunctional acetyl/propionyl-CoA carboxylase (accC) (28), were used as queries to search the genome of M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 (National Center for Biotechnology Information BioProject PRJNA64481; taxon identification number 671065) as well as metagenome assemblies from Fe(III)-oxide mats in YNP. Five of these metagenomes were obtained by using 454-Ti sequencing on samples taken on 15 July 2010: Beowulf site D (Genomes OnLine Database [GOLD] sample identification number Gs0000973), Beowulf site E (GOLD sample identification number Gs0000972), One Hundred Springs Plain site B (GOLD sample identification number Gs0000781), One Hundred Springs Plain site C (GOLD sample identification number Gs0000782), and One Hundred Springs Plain site D (GOLD sample identification number Gs0000783). Two of the metagenomes, One Hundred Springs Plain YNP_8 (GOLD sample identification number Gs0000369; sample date, 30 August 2007) and One Hundred Springs Plain YNP_14 (GOLD sample identification number Gs0000371; sample date, 7 November 2007), were sequenced by using Sanger sequencing and were reported in a larger metagenome study of 20 geothermal sites (27). Both M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 and M. yellowstonensis-like sequences from the One Hundred Springs Plain metagenomes were evaluated for pathway completeness.

Phylogenetic tree construction.

The phylogenetic relationship of type I 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratases and the biotin carboxylase subunit of bifunctional acetyl/propionyl-CoA carboxylases was examined by using MEGA5 (29). Deduced 4HCD proteins were aligned by using the PAM algorithm, and deduced AccC proteins were aligned by using the MUSCLE algorithm. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using the neighbor-joining method; bootstrap consensus trees and values were inferred from 1,000 replicates. The evolutionary distances were computed by using the Dayhoff matrix-based method.

Culture media and conditions.

All pure culture experiments and field incubations were performed at 65°C to 70°C in glass medium bottles (total volume, ∼710 ml) (part number 219439; Wheaton Science Products) with butyl rubber septum screw caps (part number 240680; Wheaton Science Products). Aqueous medium was synthesized to mimic Fe(III)-oxide spring geochemistry and to provide nutrients sufficient to support up to 109 cells ml−1 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material); 300 ml of medium was supplied to each growth vessel. Two and a half grams of ground pyrite was used as a solid-phase ferrous electron donor for each culture. Oxygen headspace was maintained at a partial pressure of >0.6 atm to serve as the electron acceptor. A total of 5 mM inorganic carbon was supplied in the form of NaHCO3 or NaH13CO3 through the bottle septum, after which the pH of the medium was readjusted to ∼2.5 with H2SO4. In some cases, the medium was supplemented with 1% yeast extract as a source of organic carbon.

Pure-culture CO2 uptake experiments.

M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 (17) was grown, as described previously, with NaH13CO3, unlabeled NaHCO3, NaH13CO3, and 1% YE; NaHCO3 and 1% YE; or 1% YE alone for ∼10 days to post-log phase (∼108 cells ml−1). Culture purity was assessed by using PCR amplification of 16S rRNA with primers for M. yellowstonensis and known Sulfolobales contaminants (primarily Sulfolobus islandicus). Biomass samples were harvested from pure cultures, centrifuged, washed in HCl overnight to remove any potential residual HCO3−, rinsed three times with deionized H2O, and lyophilized into cell pellets in preparation for isotope (δ13C) analysis via isotope ratio mass spectroscopy.

Ex situ incubations.

Approximately 3- to 4-g (wet weight) portions of Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats were excised from the outflow channels of two different Fe(II)-oxidizing geothermal springs (OSP Spring and Grendel Spring), placed into glass medium bottles containing 300 ml synthetic medium with 2.5 g autoclaved ground pyrite mineral, and then sealed with septum-containing lids. The experiment included one sample from OSP Spring, two samples from Grendel Spring that were treated as duplicates, and one sample from each spring that was killed with 0.5 mmol sodium azide. The bottles were purged with pure oxygen for approximately 15 s and brought to a slight positive pressure. Two hundred milliliters of either 13CO2 or unlabeled CO2 gas was then added through the septum. Sodium azide-killed controls were injected with 13CO2, and all samples were incubated at 65°C to 70°C for 10 days. Positive pressure was maintained in the bottles by injection of additional O2 as needed. After 10 days, biomass was harvested by centrifugation and prepared for isotope analysis, with an HCl wash, deionized H2O rinse, and lyophilization.

Isotope ratio mass spectrometry.

Stable carbon isotope ratios (δ13C) were measured by using a Thermo-Finnegan (Bremen, Germany) Delta V Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer coupled to a Costech Analytical Technologies (Valencia, CA, USA) 4010 Elemental Analyzer and a Zero-Blank autosampler. Approximately 8 to 15 mg of lyophilized iron mat biomass (which contained significant amounts of iron oxide material) or 15 to 20 mg of culture biomass (which contained significant amounts of pyrite) was placed into tin capsules (Costech Analytical Technologies) and analyzed in triplicate. Analytical sample sets included in-house Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) glutamic acid standards, which had been calibrated to U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) standard 40 (δ13C = −26.39‰) and USGS standard 41 (δ13C = +37.63‰) glutamic acid isotopic standards. Data were corrected to these standards by using the point-slope method (30). Stable-isotope content is measured as a ratio, R (e.g., 13C/12C), and reported as a delta (δ) value, where δ equals (RA/RStd −1) × 1,000 and RA and RStd are the isotope ratios of the sample and an internationally recognized standard, respectively. The standard for C isotope ratio analysis is Vienna PeeDee belemnite (VPDB). Special precaution was taken to minimize carryover between analyses. Enriched samples containing large amounts of 13C required up to three standard runs to flush the system, as measured by a return to established isotope values. Although excellent precision was obtained for both enriched and natural-abundance (NA) 13C samples, enriched samples exhibited poorer analytical precision than natural-abundance samples (standard deviations of sample measurements are reported in Table 1). This was due in part to the fact that enriched samples exceeded the optimum calibration range of the instrument. Also, relatively large sample sizes (up to 20 mg) were required, due to the low carbon contents and large amounts of iron oxide and/or pyrite; this may have influenced combustion efficiency and decreased measurement precision. Despite these caveats, the strong signal from 13C-enriched cultures and field incubation mixtures provided definitive evidence that inorganic carbon was incorporated into biomass.

TABLE 1.

Carbon isotope values of M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 biomass in growth experiments using labeled versus unlabeled CO2 and 1% yeast extract

| Growth condition | Mean δ13C value (‰) (σ) (n = 3) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| C source | MK1 biomass |

||

| Culture 1 | Culture 2 | ||

| 1% YE | −25.1 (0.04) | −24.2 (0.2) | −24.4 (0.2) |

| NA CO2 | −15.9 (0.2) | −19.3 (1.1) | −17.6 (0.8) |

| NA CO2 + 1% YE | −23.2 (0.1) | −23.2 (0.1) | |

| 13CO2 | 71,500 (14,373) | 80,637 (4,166) | |

| 13CO2 + 1% YE | 1,677 (37) | 1,540 (153) | |

Fractionation factors/mixing models.

The fractionation factor (ε) for M. yellowstonensis was determined by using the equation ε = 1,000 × ln(Rproduct/Rsubstrate), where R is the 13C/12C ratio.

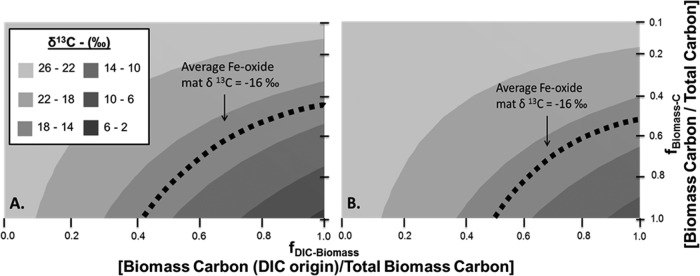

The isotopic composition of mat C was predicted by using an isotope mixing model formulated based on δ13C values of DIC, dissolved organic C (DOC), and landscape C (LC) (measured in this study) and the fractionation factors of M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 (this study) and Hydrogenobaculum-like organisms (31), which utilize 3-HP/4-HB and r-TCA carbon dioxide fixation pathways, respectively. The measured C isotope content of actual Fe(III)-oxide mat samples may contain contributions from microbial biomass of DIC origin, microbial biomass of DOC (or landscape C) origin, and exogenous landscape C. Given the difficulty in knowing absolute values of all necessary parameters, predicted mat C isotope values were obtained as a function of the ratios of microbial biomass of DIC origin relative to total microbial biomass (fBiomass-DIC, where fBiomass-DIC + fBiomass-DOC/LC = 1) and the amount of biomass C relative to total mat C (fBiomass-C, where fBiomass-C + fNonbiomass-C = 1). Fractionation factors used in the mixing model included a εM. yellowstonensis value of 2.5‰ (this study) and a εHydrogenobaculum value of 5.5‰ (reported value for Hydrogenobacter thermophilus [31]). The assumed fractionation factor for heterotrophic incorporation of organic carbon (DOC or landscape C) was 0‰ (32).

RESULTS

Genome and metagenome analysis.

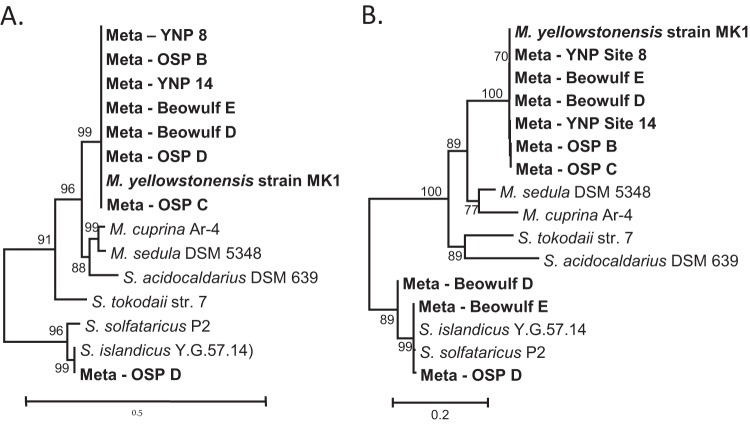

All genes for a complete 3-HP/4-HB cycle were identified in the genome of M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), which were similar to those identified in M. sedula (9, 33). Moreover, the key marker genes for this pathway (4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase [the 4HCD gene] and the biotin subunit of acetyl/propionyl-CoA carboxylase [accC]) were found in metagenome sequence assemblies from replicate Fe(III)-oxide mat samples (n = 6). The deduced protein sequences obtained from metagenome assemblies are highly similar to and group with the same sequences identified in M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 (Fig. 1). Other copies of these marker genes belonging to different Sulfolobales were also found in Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats (24), and these populations may also contribute to the fixation of CO2 in situ. PCR amplification of the 4HCD gene, accC, accB, and pccB, using primers specific to M. yellowstonensis strain MK1, further demonstrated the presence of these genes in both the isolate and Fe(III)-oxide systems (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The metagenome sequence of MK1-like populations present in Fe(III)-oxide mats (∼98 to 99% average genome nucleotide identity) contained all genes for a complete 3-HP/4-HB pathway, which were similar to those identified in strain MK1 and M. sedula (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The consistent presence of M. yellowstonensis-like 4HCD and accC genes in Fe(III)-oxide mat metagenomes suggests that the fixation of CO2 via the 3-HP/4-HB pathway is an important metabolic process conducted by M. yellowstonensis populations in situ and may result in significant transformation of CO2 to microbial biomass.

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic trees of key proteins in the 3-HP/4-HB pathway for fixation of carbon dioxide (9). (A) Type I 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase (4HCD); (B) biotin carboxylase subunit of bifunctional acetyl/propionyl-CoA carboxylase (AccC). Metallosphaera yellowstonensis-like type I 4HCD and biotin carboxylase sequences were identified in numerous replicate metagenome samples from high-temperature Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats (Beowulf sites D and E, One Hundred Springs Plain sites B and C, YNP_8, and YNP_14).

Pure-culture experiments.

Growth experiments using M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 in the presence of different C sources provided definitive evidence for the incorporation of CO2 into microbial biomass. The C isotope ratio (δ13C) of M. yellowstonensis biomass was −24.3‰ ± 0.2‰ when grown on yeast extract (YE) and ∼−18‰ ± 0.5 ‰ when grown on natural-abundance (NA) CO2 (Table 1). When 13CO2 was the sole carbon source, δ13C values of M. yellowstonensis biomass were >50,000‰ (Table 1), which demonstrated the incorporation of inorganic carbonate species (H2CO3 and aqueous CO2 [CO2(aq)] are the dominant species at pH values near 3).

We estimated the ε value for M. yellowstonensis cultures grown on NA CO2, with a measured 13C isotope composition of ∼−15.9‰ (Rsubstrate = 0.0114159) (Table 1). The average value of strain MK1 biomass (−18.45‰; Rproduct = 0.0114445) measured in two replicate experiments was used to estimate a value of ε for M. yellowstonensis of ∼2.5‰. Although not the primary focus of our study, this ε value is similar to that observed for M. sedula (3.1‰) (31).

When M. yellowstonensis was supplied with 1% YE and CO2 simultaneously, δ13C values showed that carbon constituents from YE were the dominant sources used to build microbial biomass (Table 1). The 13C isotope content of M. yellowstonensis biomass grown on YE and NA CO2 was slightly higher (δ13C = −23.3‰) than that of biomass grown on YE alone (δ13C = −24.3‰), which suggested some incorporation of inorganic carbon. The same pattern was observed when strain MK1 was grown on YE plus 13CO2. δ13C values were higher (∼1,600‰) than those of biomass grown on YE alone (δ13C = −24.3‰) but not nearly as high as 13C values obtained by using 13CO2 alone. Together, these data showed that M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 is capable of growth using either CO2 or organic C and that these processes may operate simultaneously (34).

Ex situ assays using Fe(III)-oxide mats.

Evidence of a complete 3-HP/4-HB pathway in M. yellowstonensis strain MK1 is consistent with the observed incorporation of CO2 using 13CO2. The presence of these same genes in metagenome assemblies obtained from Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats (Fig. 1) suggested that this population may fix carbon dioxide in situ. To measure the uptake of CO2 in Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats, excised mat samples were incubated ex situ with natural-abundance CO2 and 13CO2. The uptake of 13CO2 into live Fe(III)-oxide mats was observed in two different geothermal communities studied (Table 2). Small increases in the 13C content of killed controls were also observed, but these values were considerably lower than those observed with live mats and may be due to abiotic exchange between 13CO2 and solid phases and/or incomplete sterility achieved by using sodium azide.

TABLE 2.

Carbon isotope composition of microbial mat samples incubated after ex situ experiments to detect CO2 uptake in Fe(III)-oxide microbial mat communities from Norris Geyser Basin, YNP, October 2011

| Treatment | Samplea | δ13C value (‰) (σ) (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 NA, live mat | OSP_B | −16.1 (0.1) |

| CO2 NA, live mat | GRN_D | −13.8 (0.2) |

| 13CO2, live mat | OSP_B, assay 1 | 1,278 (61) |

| 13CO2, live mat | GRN_D, assay 1 | 1,267 (95) |

| 13CO2, live mat | GRN_D, assay 2 | 1,458 (54) |

| 13CO2, killed | OSP_B | 27.3 (2.0) |

| 13CO2, killed | GRN_D | 46.9 (3.7) |

OSP_B, One Hundred Springs Plain Spring site B; GRN_D, Grendel Spring site D.

Carbon isotope composition of iron geothermal systems.

The 13C compositions (δ13C) of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), Fe(III)-oxide mat carbon, and various landscape carbon samples were analyzed to evaluate the likely contributions of these potential C sources to microorganisms within native Fe mat communities (Table 3). The 13C isotope contents of landscape components such as leaves, soil, and animal dung from around the spring sites were characteristic of C3 photosynthesis (δ13C, ∼−26‰) and are consistent with predictions based on the high latitude and elevation of Yellowstone National Park (35, 36). The 13C composition of DOC averaged −22.2‰ (σ = 1.6‰) across the three geothermal systems studied and was slightly higher (Table 3) than that of landscape C. Conversely, the 13C content of the DIC fraction ranged from −5.1‰ to 0.49‰ across the three springs (Table 3). Relative to either DOC or landscape C, the DIC fraction has significantly high 13C content and provides a basis for interpreting the isotopic composition of mat biomass. The mean δ13C of three Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats (n = 14) was −16.1‰ (σ= 1.3‰) and ranged from −16.5‰ in samples from Grendel Spring (GRN_D) to −15.0‰ in samples from One Hundred Springs Plain (OSP_B) (Table 3). These values fall between the 13C compositions of end-member DIC and DOC (or landscape C) and show that Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats contain carbon of both organic and inorganic origins and that DIC makes a significant contribution to mat carbon.

TABLE 3.

Carbon isotope ratios of dissolved inorganic carbon, dissolved organic C, and total C present in Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats collected from Norris Geyser Basin, YNP, 2011 to 2013

| Carbon pool | Samplea | δ13C value (‰) (σ) (no. of samples) | Concn (mg kg−1) (σ) (no. of samples)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIC | OSP_B | −5.1 (0.8) (3) | 1.5 (0.8) (3) |

| BE_D | −3.2 (0.2) (4) | 2.0 (1.9) (4) | |

| GRN_D | −0.5 (2.6) (3) | 0.6 (0.1) (3) | |

| DOC | OSP_B | −21.0 (1.6) (3) | 0.8 (0.5) (3) |

| BE_D | −22.3 (1.0) (5) | 0.8 (0.7) (4) | |

| GRN_D | −23.0 (2.1) (4) | 0.6 (0.2) (3) | |

| Microbial matc | OSP_B | −15.0 (1.8) (3) | 10,200 |

| BE_D | −16.4 (1.1) (8) | 11,500 | |

| GRN_D | −16.5 (0.9) (3) | 7,600 |

OSP_B, One Hundred Springs Plain Spring site B; BE_D, Beowulf Spring site D; GRN_D, Grendel Spring site D.

Expressed as mg per liter for DIC and DOC and mg per kg (dry weight) for microbial mat C.

The total C level was determined on aggregate mat samples from each site during this time frame (n = 1). The range of 0.8 to 1.5% total C agrees favorably with values observed in previous studies (16).

DISCUSSION

The incorporation of 13CO2 into live microbial Fe(III)-oxide mats demonstrated that organisms within these communities are capable of CO2 fixation and that this is an important process in situ. We also showed that pure cultures of M. yellowstonensis strain MK1, a significant community member in these Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats, grew using CO2 as the sole C source in the absence of yeast extract (fractionation factor [ε] = 2.5‰). High-temperature acidic Fe(III)-oxide mat communities are typically composed of 5 to 7 major phylotypes, including M. yellowstonensis and Hydrogenobaculum-like populations, which represent 10 to 20% and 2 to 10% of the community, respectively, based on random sequence reads of mature Fe mat metagenomes (19, 24, 25). Other archaea present in these communities include members of two novel archaeal groups, the Thaumarchaeota and the Euryarchaeota (Thermoplasmatales-like), as well as other crenarchaea within the orders Thermoproteales and Desulfurococcales (19, 24, 25). However, sequence assemblies corresponding to these populations do not contain evidence of marker genes for known CO2 fixation pathways and appear to be primarily heterotrophic (18, 19, 24, 25, 37, 41). Despite the diversity of archaea in these Fe(II)-oxidizing communities, the only known CO2 fixation pathways found in metagenome sequence analyses included the 3-HP/4-HB pathway (contributed by M. yellowstonensis-like and other Sulfolobales populations) and the r-TCA cycle (contributed by Hydrogenobaculum-like populations). Thus, our working hypothesis is that M. yellowstonensis- and Hydrogenobaculum-like populations are the primary members of mature Fe(III)-oxide mat communities that contribute to the fixation of CO2 into mat biomass.

Isotopic analysis of the major carbon pools (DIC, DOC, landscape carbon, and Fe mat carbon) from three geothermal sites showed that mat carbon exhibits an isotopic composition of ∼−16.1‰ (σ = 1.3‰) (Table 3), which is between the 13C contents of DIC and DOC (or landscape C) end members (Table 3). Therefore, the 13C values of mat C can be explained as a mixture of biomass carbon originating from DIC (i.e., autotrophy), DOC, and/or landscape C (heterotrophy) and, simultaneously, as a possible mixture of biomass carbon and exogenous landscape C from foreign sources (e.g., plant material, insects, landscape detritus, and eukaryal biomass), although any visible macroscopic debris was avoided during sampling. An isotope mixing model (Fig. 2) was developed to predict the isotopic composition of C present in Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats as a function of (i) the fraction of biomass C of DIC origin (fDIC-Biomass) and (ii) the fraction of biomass C relative to total mat C (fBiomass-C) (Fig. 2). Given the similarity of δ13C values for DOC and landscape C (−22 to −26‰), it is not possible to distinguish heterotrophic biomass generated from either of these carbon sources. Carbon isotope fractionation factors for heterotrophic metabolism are near 0‰ (32); consequently, the 13C content of biomass C generated from either DOC or landscape C will also range from ∼−22 to −26‰.

FIG 2.

Predicted δ13C content of Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats as a function of the fraction of microbial biomass originating from dissolved inorganic C (DIC) relative to total biomass C (x axis) and the fraction of biomass C relative to total Fe mat C (y axis). Fixation of CO2 may occur via the 3-HP/4-HB pathway (i.e., M. yellowstonensis) (A) or the r-TCA pathway (i.e., Hydrogenobaculum sp.) (B). The isotope mixing model was based on the measured isotope composition of DIC, DOC, and landscape C sources and specific fractionation factors for the conversion of CO2 to microbial biomass (see Materials and Methods). The average observed 13C content (δ13C, ∼−16‰) (dotted line) from replicate Fe(III)-oxide microbial mats shows that at least 42 to 50% of the biomass carbon has a DIC origin.

Two different isotopic mixing models were evaluated based on autotrophic contributions from either the 3-HP/4-HB cycle (M. yellowstonensis) or the r-TCA cycle (Hydrogenobaculum spp.) (Fig. 2). Fractionation factors for the conversion of DIC to microbial biomass were obtained either in this study (M. yellowstonensis, ε = 2.5‰) or from literature sources (Hydrogenobaculum, ε = 5.5‰ [31]). Estimates of the autotrophic contribution to biomass C (fDIC-Biomass) (x axis in Fig. 2) are relatively insensitive to the range of fractionation factors available for the conversion of CO2 to microbial biomass, due to the large differences in δ13C-DIC versus δ13C-DOC values. Although the fixation of CO2 can also be weighted based on the relative ratio of the amount of Metallosphaera to the amount of Hydrogenobaculum observed in random metagenome sequencing (∼4:1), the model solution falls between those shown for the two cases based on either organism alone (Fig. 2A and B).

The average observed Fe(III)-oxide mat δ13C value of −16.1‰ (Fig. 2, dotted line) is constrained by a unique set of the fraction of DIC in microbial biomass (fDIC-Biomass) versus the fraction of microbial biomass C relative to total Fe mat C (fBiomass-C). The observed 13C isotopic composition can be explained only when the fDIC-Biomass ranges from about 0.42 to >0.99, depending on the dilution of microbial biomass C with nonmicrobial C from landscape sources (Fig. 2). Greater contributions of nonmicrobial landscape C to Fe mat C result in correspondingly higher estimates of fDIC-Biomass. In the simplest case, where the Fe mat contains no exogenous landscape C (fBiomass-C = 1), the mat 13C content is explained by fDIC-Biomass values of ∼0.42 to 0.50, depending on whether CO2 is fractionated via the 3-HP/4-HB or r-TCA pathway (Fig. 2A and B). Interestingly, this is greater than, but agrees favorably with, the absolute abundance of the two primary DIC-fixing populations identified previously by using metagenome sequencing (the combined abundance of Metallosphaera and Hydrogenobaculum populations has ranged from 20 to 35% of the community). Growth and turnover rates of all populations present in these communities may not be equal, and less abundant, faster-growing autotrophic populations (relative to heterotrophic populations) could also influence observed mat δ13C values. It is possible that heterotrophic populations present in these communities utilize biomass or metabolites produced only from autotrophs (i.e., classical primary production), which would correspond to fDIC-Biomass values close to 1. In this scenario, nearly 50 to 60% of the total mat C would have to be nonmicrobial C from landscape sources (Fig. 2).

The total C content of Fe-oxide microbial mats is ∼1%, and only a fraction of this carbon (as much as 10%) can be accounted for in estimates of live-cell counts (∼109 cells g−1) (18, 24, 25, 38), although the filamentous nature of specific phylotypes makes accurate cell counting difficult. The remaining carbon present in Fe(III)-oxide mats is comprised of dead microbial biomass generated in situ and/or exogenous landscape C. The sorption of DOC by Fe(III)-oxides may also contribute to mat C (39); however, the available surface sites of the amorphous Fe(III)-oxide phases present in these systems are nearly saturated with arsenate as bidentate surface complexes (16). Consequently, future efforts should focus on evaluation of live versus dead biomass C, other solid phases of exogenous C, and a more detailed characterization of components comprising the DOC fraction.

Results from this study have important implications for possible microbial interactions occurring among community members in thermoacidic Fe(II)-oxidizing microbial communities. The isotopic composition of total mat C in all three springs showed that CO2 fixation is an important process in situ, which provides a source of organic carbon and numerous possible substrates for heterotrophic community members. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that M. yellowstonensis and Hydrogenobaculum spp. serve founding roles in the development of Fe(III)-oxide mats and community succession (23, 40). Now that the incorporation of inorganic carbon by members of these communities has been firmly established, more detailed trophic cascades and metabolite interactions may be resolvable by using stable-isotope probing coupled with metabolomic and/or proteomic analyses. Colonization by one or both of the predominant CO2-fixing populations (Metallosphaera and Hydrogenobaculum) may be a necessary condition for establishing acidothermophilic Fe(III)-oxide mat communities, which also support significant heterotrophic diversity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge and appreciate funding from the National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate and Education Training (IGERT) Program (DGE 0654336) for support to R.M.J.; the Howard Hughes Undergraduate Fellowship Program for support to L.M.W.; the Department of Energy Genome Science Program, Microbial Interactions Foundational Science Focus Area (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory subcontract 112443 to Montana State University); and the Montana Agricultural Experiment Station (project 911300 to W.P.I.).

We appreciate research permits (permit no. YELL-5568, 2007-2010) managed by C. Hendrix and S. Gunther (Center for Resources, YNP) and discussion with J. Beam, Z. Jay, M. Kozubal, and M. Romine.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 February 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03416-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karner MB, DeLong EF, Karl DM. 2001. Archaeal dominance in the mesopelagic zone of the Pacific Ocean. Nature 409:507–510. 10.1038/35054051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearson A, McNichol AP, Benitez-Nelson BC, Hayes JM, Eglinton TI. 2001. Origins of lipid biomarkers in Santa Monica Basin surface sediment: a case study using compound-specific δ14C analysis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65:3123–3137. 10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00657-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Könneke M, Bernhard AE, De la Torre JR, Walker CB, Waterbury JB, Stahl DA. 2005. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437:543–546. 10.1038/nature03911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tully BJ, Nelson WC, Heidelberg JF. 2012. Metagenomic analysis of a complex marine planktonic thaumarchaeal community from the Gulf of Maine. Environ. Microbiol. 14:254–267. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huber H, Huber R, Stetter KO. 2006. Thermoproteales, p 10–22 In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E. (ed), The prokaryotes. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huber H, Prangishvili D. 2006. Sulfolobales, p 23–51 In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E. (ed), The prokaryotes. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber H, Stetter KO. 2006. Desulfurococcales, p 52–68 In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E. (ed), The prokaryotes. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hügler M, Huber H, Stetter KO, Fuchs G. 2003. Autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways in archaea (Crenarchaeota). Arch. Microbiol. 179:160–173. 10.1007/s00203-002-0512-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg IA, Kockelkorn D, Buckel W, Fuchs G. 2007. A 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation pathway in archaea. Science 318:1782–1786. 10.1126/science.1149976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber H, Gallenberger M, Jahn U, Eylert E, Berg IA, Kockelkorn D, Eisenreich W, Fuchs G. 2008. A dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon assimilation cycle in the hyperthermophilic archaeum Ignicoccus hospitalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7851–7856. 10.1073/pnas.0801043105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L-M, Offre PR, He J-Z, Verhamme DT, Nicol GW, Prosser JI. 2010. Autotrophic ammonia oxidation by soil Thaumarchaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:17240–17245. 10.1073/pnas.1004947107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rusch DB, Halpern AL, Sutton G, Heidelberg KB, Williamson S, Yooseph S, Wu D, Eisen JA, Hoffman JM, Remington K, Beeson K, Tran B, Smith H, Baden-Tillson H, Stewart C, Thorpe J, Freeman J, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Venter JE, Li K, Kravitz S, Heidelberg JF, Utterback T, Rogers Y-H, Falcón LI, Souza V, Bonilla-Rosso G, Eguiarte LE, Karl DM, Sathyendranath S, Platt T, Bermingham E, Gallardo V, Tamayo-Castillo G, Ferrari MR, Strausberg RL, Nealson K, Friedman R, Frazier M, Venter JC. 2007. The Sorcerer II global ocean sampling expedition: northwest Atlantic through eastern tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol. 5:e77. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramos-Vera WH, Berg IA, Fuchs G. 2009. Autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation in Thermoproteales revisited. J. Bacteriol. 191:4286–4297. 10.1128/JB.00145-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konhauser KO. 1998. Diversity of bacterial iron mineralization. Earth Sci. Rev. 43:91–121. 10.1016/S0012-8252(97)00036-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordstrom DK, Southam G. 1997. Geomicrobiology of sulfide mineral oxidation. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 35:361–390 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inskeep WP, Macur RE, Harrison G, Bostick BC, Fendorf S. 2004. Biomineralization of As(V)-hydrous ferric oxyhydroxide in microbial mats of an acid-sulfate-chloride geothermal spring, Yellowstone National Park. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68:3141–3155. 10.1016/j.gca.2003.09.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozubal MA, Macur RE, Korf S, Taylor WP, Ackerman GG, Nagy A, Inskeep WP. 2008. Isolation and distribution of a novel iron-oxidizing crenarchaeon from acidic geothermal springs in Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:942–949. 10.1128/AEM.01200-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozubal MA, Romine M, Jennings RM, Jay ZJ, Tringe SG, Rusch DB, Beam JP, McCue LA, Inskeep WP. 2013. Geoarchaeota: a new candidate phylum in the Archaea from high-temperature acidic iron mats in Yellowstone National Park. ISME J. 7:622–634. 10.1038/ismej.2012.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inskeep WP, Jay ZJ, Herrgard MJ, Kozubal MA, Rusch DB, Tringe SG, Macur RE, Jennings RM, Boyd ES, Spear JR, Roberto FF. 2013. Phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenome sequence from high-temperature archaeal habitats demonstrate linkages between metabolic potential and geochemistry. Front. Microbiol. 4:95. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takacs-Vesbach C, Inskeep WP, Jay ZJ, Herrgard MJ, Rusch DB, Tringe SG, Kozubal MA, Hamamura N, Macur RE, Fouke BW, Reysenbach A-L, McDermott TR, Jennings RM, Hengartner NW, Xie G. 2013. Metagenome sequence analysis of filamentous microbial communities obtained from geochemically distinct geothermal channels reveals specialization of three Aquificales lineages. Front. Microbiol. 4:84. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyd ES, Leavitt WD, Geesey GG. 2009. CO2 uptake and fixation by a thermoacidophilic microbial community attached to precipitated sulfur in a geothermal spring. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4289–4296. 10.1128/AEM.02751-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hügler M, Huber H, Molyneaux SJ, Vertriani C, Sievert SM. 2007. Autotrophic CO2 fixation via the reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle in different lineages within the phylum Aquificae: evidence for two ways of citrate cleavage. Environ. Microbiol. 9:81–92. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macur RE, Langner HW, Kocar BD, Inskeep WP. 2004. Linking geochemical processes with microbial community analysis: successional dynamics in an arsenic-rich, acid-sulphate-chloride geothermal spring. Geobiology 2:163–177. 10.1111/j.1472-4677.2004.00032.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozubal MA, Macur RE, Jay ZJ, Beam JP, Malfatti SA, Tringe SG, Kocar BD, Borch T, Inskeep WP. 2012. Microbial iron cycling in acidic geothermal springs of Yellowstone National Park: integrating molecular surveys, geochemical processes, and isolation of novel Fe-active microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 3:109. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inskeep WP, Rusch DB, Jay ZJ, Herrgard MJ, Kozubal MA, Richardson TH, Macur RE, Hamamura N, Jennings RM, Fouke BW, Reysenbach A-L, Roberto F, Young M, Schwartz A, Boyd ES, Badger JH, Mathur EJ, Ortmann AC, Bateson M, Geesey G, Frazier M. 2010. Metagenomes from high-temperature chemotrophic systems reveal geochemical controls on microbial community structure and function. PLoS One 5:e9773. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg IA, Kockelkorn D, Ramos-Vera WH, Say RF, Zarzycki J, Hügler M, Birgit E, Alber BE, Fuchs G. 2010. Autotrophic carbon fixation in archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:447–460. 10.1038/nrmicro2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inskeep WP, Jay ZJ, Tringe SG, Herrgård MJ, Rusch DB, YNP Metagenome Project Steering Committee and Working Group Members 2013. The YNP metagenome project: environmental parameters responsible for microbial distribution in the Yellowstone geothermal ecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 4:67. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hügler M, Krieger RS, Jahn M, Fuchs G. 2003. Characterization of acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylase in Metallosphaera sedula: carboxylating enzyme in the 3-hydroxypropionate cycle for autotrophic carbon fixation. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:736–744. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coplen TB, Brand WA, Gehre M, Gröning M, Meijer HAJ, Toman B, Verkouteren RM. 2006. New guidelines for δ13C measurements. Anal. Chem. 78:2439–2441. 10.1021/ac052027c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.House CH, Schopf JW, Stetter KO. 2003. Carbon isotopic fractionation by archaeans and other thermophilic prokaryotes. Org. Geochem. 34:345–356. 10.1016/S0146-6380(02)00237-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boschker HTS, Middelburg JJ. 2002. Stable isotopes and biomarkers in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 40:85–95. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkins AS, Han Y, Bennett RK, Adams MWW, Kelly RM. 2013. Role of 4-hydroxybutyrate-CoA synthetase in the CO2 fixation cycle in thermoacidophilic archaea. J. Biol. Chem. 228:4012–4022. 10.1074/jbc.M112.413195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auernik KS, Kelly RM. 2010. Physiological versatility of the extremely thermoacidophilic archaeon Metallosphaera sedula supported by transcriptomic analysis of heterotrophic, autotrophic, and mixotrophic growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:931–935. 10.1128/AEM.01336-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehleringer JR, Monson RK. 1993. Evolutionary and ecological aspects of photosynthetic pathway variation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 24:411–439. 10.1146/annurev.es.24.110193.002211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stowe LG, Teeri JA. 1978. The geographic distribution of C4 species of the Dicotyledonae in relation to climate. Am. Nat. 112:609–623. 10.1086/283301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beam JP, Jay ZJ, Kozubal MA, Inskeep WP. 2013. Niche specialization of novel Thaumarchaeota to oxic and hypoxic acidic geothermal springs of Yellowstone National Park. ISME J. 10.1038/ismej.2013.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein HC, Beam JP, Kozubal MA, Carlson RP, Inskeep WP. 2013. In situ analysis of oxygen consumption and diffusive transport in high-temperature acidic iron-oxide microbial mats. Environ. Microbiol. 15:2360–2370. 10.1111/1462-2920.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ali MA, Dzombak DA. 1996. Competitive sorption of simple organic acids and sulfate on goethite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 30:1061–1071. 10.1021/es940723g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beam JP, Jay ZJ, Kozubal MA, Inskeep WP. 2011. Distribution and ecology of thaumarchaea in geothermal environments, abstr PA-009 Abstr. 11th Int. Conf. Thermophiles Res., Big Sky, MT [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jay ZJ, Rusch DB, Tringe SG, Bailey C, Jennings RM, Inskeep WP. 2014. Predominant Acidilobus-like populations from geothermal environments in Yellowstone National Park exhibit similar metabolic potential in different hypoxic microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80:294–305. 10.1128/AEM.02860-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.