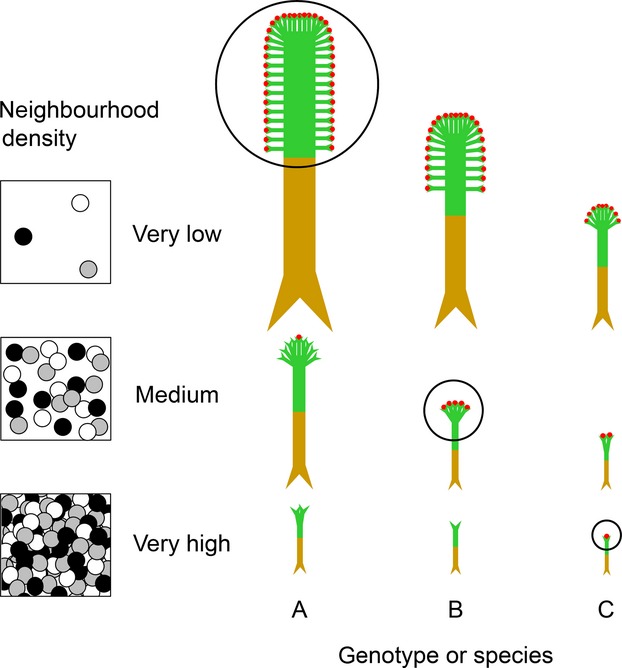

Figure 4.

Symbolic representation of the ‘reproductive-economy-advantage’ hypothesis. Hypothetical plants (genotypes or species) A, B, and C are represented by differently colored circles (white/gray/black) within three square ‘plots’ showing different neighborhood densities of resident seeds, which is the only stage in which the three plants – as embryos – are all the same size. In each case, the ‘stick-plant’ symbols represent the relative body sizes of A, B, and C following emergence and growth to final developmental stage. The maximum potential body sizes (MAX) for A, B, and C can be expressed only when neighborhood density is very low (top row), where A has the largest MAX and hence the highest fecundity (indicated for each density by the collection of small red circles at the ends of plant ‘shoots’, delineated within the back circular outlines), and where it is thus favored by natural selection. Plant A therefore also has (as a trade-off) the largest minimum reproductive threshold size (MIN) (c.f. Fig. 1), which is expressed within a higher (intermediate)-density neighborhood (middle row). Here, plant B is favored by natural selection because its smaller MIN permits a higher fecundity than A, and its larger MAX permits a higher fecundity than C. Under very high neighbor density (bottom row), however, where all resident plants are severely suppressed in size, plant C has the highest fecundity (and is thus favored by natural selection) because it has the smallest MIN (which imposes, as a trade-off, the smallest MAX; c.f. Fig. 1). Under these conditions, plants of both A and B die without sex, because MIN for both is too large. Accordingly, contrary to the ‘size-advantage’ hypothesis, selection in favor of relatively large MAX (plant A) occurs, not under the most crowded conditions, but only within local neighborhoods where competition effects are relatively weak (top row) – because only here can MAX (and its potential fitness advantage) be realized. The preponderance of relatively small resident species within most natural vegetation, therefore, can be at least partially accounted for by a preponderance there of severely crowded neighborhoods (bottom row).