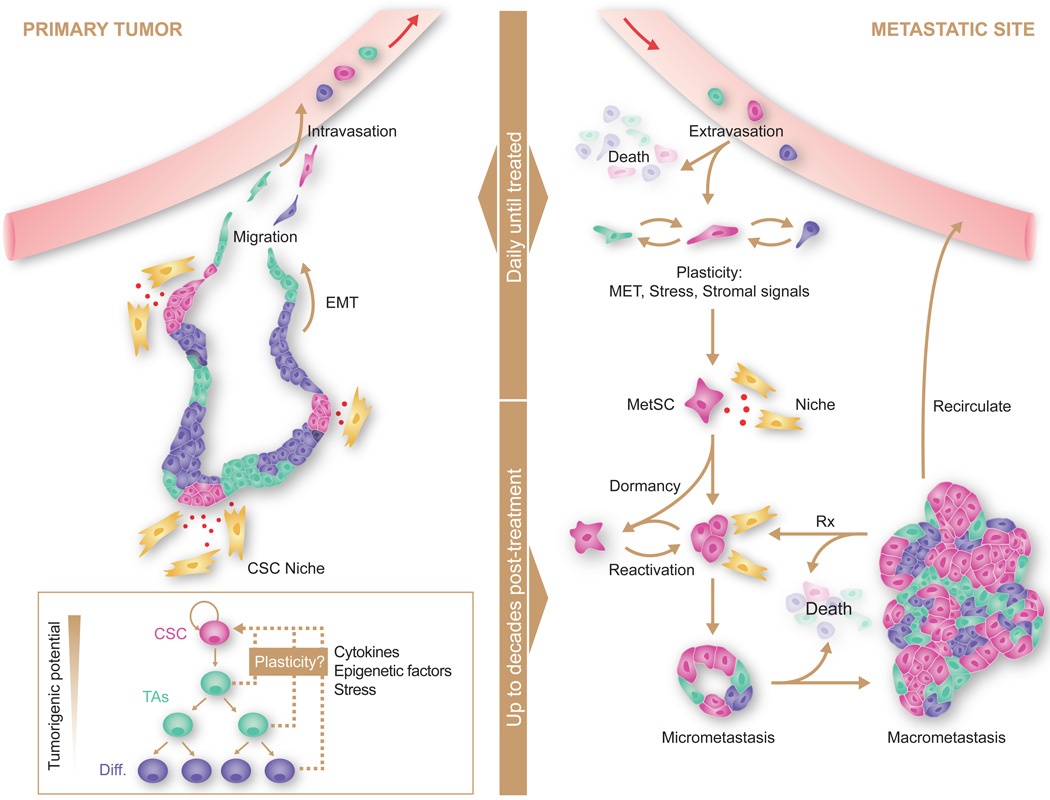

Figure 2. Sources, dissemination, dormancy, and outgrowth of MetSCs.

Several types of cancer display a hierarchical organization with CSCs being the only cell type with long-term self-renewal potential. The progeny of CSCs –the transit amplifying progenitors (TAs) and their differentiated derivatives– are short lived and have a lower tumorigenic potential. Conversion of non-CSCs into CSCs occurs in certain types of cancer and can be triggered by cytokines and stress conditions. CSCs interact with microenvironmental niches that sustain the tumor-perpetuating potential of the cells. Both CSCs and non-CSCs can display migratory behavior at the invasive front of primary tumors, frequently associated with an EMT. Intravasation, circulation, and extravasation of cancer cells in these various states can occur continuously until the primary tumor is removed. Survival of disseminated cancer cells at distant sites is a limiting step, as the vast majority of infiltrating cancer cells die. The survivors that are endowed with tumor-initiating capacity constitute MetSCs. Cells that had previously undergone an EMT must reacquire epithelial traits and co-opt a supportive stromal niche in order to thrive in the new environment. Additionally, disseminated non-CSCs may convert into MetSCs through still poorly understood processes of phenotypic plasticity. MetSCs may generate progeny and give rise to overt metastasis right after infiltrating the host tissue. More frequently, however, disseminated cancer cells enter a dormant state that can last for decades and is largely resistant to current therapies. Upon exit from quiescence, MetSCs may regenerate their lineage in the host organ and release metastatic progeny into the circulation to start secondary lesions in the same or other organs. Treatment of overt metastasis seldom results in eradication of the disease, as residual MetSCs frequently regenerate the tumor after each drug treatment cycle.