Abstract

Culturally-driven spatial biases affect the way people interact with and think about the world. We examine the ways in which spatial presentation of stimuli affects learning and memory in preschool-aged children in the USA and Israel. In Experiment 1, preschoolers in both cultures were given a spatial search task in which they were asked to utilize verbal labels (letters of the alphabet) to match the hiding locations of two monkeys. The labels were taught to the children in either a left-to-right or right-to-left fashion to assess whether performance on this task is affected by directionality of labeling. English-speaking children performed better on the spatial search task when locations were labeled in a left-to-right fashion, while Hebrew-speaking children exhibited higher performance when labels were taught in a right-to-left fashion. In Experiment 2, English-speaking preschoolers were given a modified task in which the verbal label was a non-ordinal stimulus type (colors). These children showed no subsequent advantage on the task for spatial presentations which were culturally-consistent (left-to-right) relative to culturally-inconsistent (right-to-left). These findings support the hypothesis that culturally-consistent spatial layout improves learning and memory, and that this benefit is reduced or absent when information lacks ordinal properties.

Keywords: Spatial Cognition, SNARC effect, Preschoolers, Culture

The provocative idea that language influences thought (Sapir, 1929; Whorf, 1956) has prompted much research focusing on the intersection of language, culture and cognition, which in turn has revealed that the surrounding environment and its accompanying language influences fundamental psychological capacities such as spatial processing and numerical cognition (Boroditsky, 2001- but see Chen, 2007 and January & Kako, 2007; Bowerman, 1996; Levinson, 1996; McDonough, Choi, & Mandler, 2003; Pica, Lemer, Izard, & Dehaene, 2004). For example, English-speaking adults respond to linguistic stimuli in a spatially-biased manner; they tend to draw trajectories of actions along the horizontal plane in the left-to-right direction, draw agents of an action to the left of where they draw objects of actions, and are significantly faster at matching sentences to pictures if the pictures follow these same patterns (Chatterjee, Southwood & Basilico, 1999). Arabic-speaking adults, whose language is presented in a right-to-left direction, exhibit opposite spatial biases in these tasks, suggesting that a linguistically-driven deployment of attention when reading is responsible for these effects (Maas and Russo, 2003).

Studies like these support the idea that spatial associations affect the way we think, and that this influence is a reflection of both our language and the way our cultures orient us towards the world. Further evidence for the strong influences of culture and language have been found in the way that both spatial-temporal and spatial-numeric mappings are modulated by cultural factors. People graphically lay out time in a way that is consistent with the directionality of the language they speak (Tversky, Kugelmass, & Winter, 1991). Furthermore, people’s implicit spatial representations of time vary across languages (Fuhrman & Boroditsky, 2010). When English speakers were asked to make rapid temporal order judgments, they were faster to make “earlier” judgments when the “earlier” response was made with the left response key than with the right response key while Hebrew speakers showed the opposite pattern.

The SNARC (Spatial Numerical Association of Response Codes; Dehaene, Bossini, & Giraux, 1993) effect, in which lateralized behavioral responses differ depending upon the numerical magnitude presented, is another example of spatial associations influenced by cultural factors. This lateral mapping is seen in studies that support the existence of a conceptual spatial-numerical continuum, or ‘mental number line’ (Fischer, 2003; Zorzi, Priftis, & Umilta, 2002; Priftis, Zorzi, Meneghello, Marenzi, & Umilta, 2006; see Göbel, Shaki, & Fischer, 2011; Hubbard, Piazza, Pinel, & Dehaene, 2005; Wood, Willmes, Nuerk, & Fischer, 2008 for reviews). Experiments manipulating different factors in an attempt to impact the SNARC effect showed that although the direction of the effect did not vary with handedness or hemispheric dominance, it was influenced by the direction of writing; Iranian-French subjects, whose first Persian language is one written in a right-to-left fashion, showed a faded SNARC effect commensurate with the amount of time spent in a French culture (Dehaene et al.,1993), indicative that the SNARC effect is mediated by degree of literacy in a language. Indeed, a study of multiple populations with varying degrees of Arabic and English literacy showed that the SNARC effect was reversed in Arabic speakers, lessened in bilinguals, and not present in an illiterate population (Zebian, 2005; see also Shaki, Fischer & Göbel, 2012, for similar results with literate Arabic, Hebrew, and English speakers, and illiterate Amharic-speakers from Ethiopia). Furthermore, individuals bilingual in Hebrew (written right-to-left) and Russian (written left-to-right) exhibited a SNARC effect specific to whichever language had been primed directly before the critical task, demonstrating that cultural frame of mind impacts the manner in which space and number are linked (Shaki & Fischer, 2008; Fischer, Shaki, & Cruise, 2009).

The differences in the SNARC effect as a result of reading directionality (Dehaene et al, 1993; Shaki & Fischer, 2008; Zebian, 2005), as well as the finding that this effect in traditional SNARC tasks does not come about until middle childhood (Berch, Foley, Hill, & Ryan, 1999), are generally taken as evidence that these spatial biases require many years of enculturation. Further, Tversky et al. (1991) found no consistent impact of language directionality or culture on elementary school children’s choice to present information about increasing quantity in a left-to-right or right-to-left manner, although they did find evidence for cultural impacts on time/space mapping by 5 years of age (see also Koerber & Sodian, 2008). However, these findings have been challenged by de Hevia and Spelke (2009), who showed conceptual interference of number during a spatial line bisection task as early as five years of age. Additionally, Opfer and colleagues (Opfer, Thompson & Furlong, 2010; Opfer & Furlong, 2011) examined spatial-numeric associations in 4-year-olds and showed that even preschoolers expect numbers to be ordered from left to right during both a counting task and when adding or subtracting physical objects. Similarly, Shaki et al. (2012), who studied preschool children in a variety of linguistic environments, found that English-speaking preschoolers systematically count objects from left to right.

To examine the potential impact of this bias on memory and learning, Opfer et al. (2010, 2011) employed a relational match-to-sample task (DeLoache, 1987; Loewenstein & Gentner, 2005) to elicit spatial-numerical mappings. In this task, the authors assigned children to either a left-right condition (LR) or a right-left condition (RL). LR children saw an enticing object revealed in a sample box in one of seven locations that had been verbally numbered (via oral naming) from left to right, and subsequently had to locate a companion object in a location on a matching box’s compartment that shared the same (oral) numerical label. RL subjects performed the same task, but their locations had been labeled in a right-to-left increasing numerical fashion. Children who were taught using the left-to-right numerical labeling searched more accurately and quickly than children whose labels were taught from right to left. Opfer & Furlong (2011) replicated this finding and found that this effect arose as a function of spatial-numerical interactions specifically during initial encoding of the labels and not performance. The left-to-right labeling of the sample box (and not the matching box) was the main determinant of whether children used a successful strategy.

This set of studies leaves open several questions regarding the nature and development of this spatial-numerical interaction. First, to what extent is this finding specific to the link between number and space? Previous work has suggested that these directional encoding biases are initially linked specifically to numeric symbols (de Hevia & Spelke, 2009), but it may be that any ordinal information presented in a culturally congruent manner are easier to encode. Indeed, research has shown that global, abstract ordinal or relational reasoning (A>B, B>C, therefore A>C) interacts with space much in the same way as number. For example, Prado, Ven der Henst & Noveck (2008) found that participants are faster at identifying pairs at the initial points of a letter string (AB, BC, AC) with their left hands and pairs at the end points of a letter string (CD, DE, CE) with their right hands. This effect is analogous to the response-side effect seen with numbers, leading some to suggest that ordinal, but not magnitude, information is necessary for spatial coding (Previtali, de Hevia & Girelli, 2010). SNARC-like effects have also been found for non-numerical items such as letters, months of the year, days of the week, and tones of different pitches (Gevers, Reynvoet, & Fias, 2003, 2004; Rusconi, Kwan, Giordano, Umilta, & Butterworth, 2006). Given these findings, it is possible that enhanced performance by children presented with left-right number labeling by Opfer et al. (2010) and Opfer and Furlong (2011) is due not to a precocious mapping of space and number, but rather is part of a larger phenomenon in which any ordinal information presented left to right is more readily encoded and utilized along a spatial dimension.

This prospect prompts a second question of interest: To what extent is the ease of spatial mapping of these two concepts (a serially-presented sequence of information and a spatial continuum) determined by the culture and language of the child? Previous work shows that 3–4-year-olds use generic linear structure to map temporal relations onto space, and only by age 5 do they mostly use culturally-consistent mappings (Koerber & Sodian, 2008; Tversky et al., 1991). These findings, alongside those on the malleability of spatial biases as a function of reading directionality (Zebian, 2005), suggest that by the time a child develops these spatial biases, a culturally-distinct pattern of behavior will appear. Thus if the preschoolers in the Opfer et al. (2010, 2011) studies experienced heightened success in the LR condition because of cultural factors (such as an emphasis on left-to-right directionality when presented with counting by caregivers, as suggested by the authors), an opposite pattern would emerge in children of the same age enculturated to an environment that emphasized right-to-left directionality. However, if the behavior of the Opfer et al. (2010, 2011) American sample was due to an innate bias in preschool children to favor left-right spatial-numerical mapping very early in development and before the advent of literacy, one would find a similar advantage for left-right labeling no matter the cultural background of the population. The possibility of an innate preference for left-to-right spatial-numerical mapping has some support from work on chicks and infants. Young domestic chicks (Gallus gallus) preferentially encode ordered stimuli from the left side of space (Rugani, Kelly, Szelest, Regolin, & Vallortigara, 2010), suggesting a mental allocation of leftward attention during ordering. Additionally, a growing number of studies suggest an untrained link between number and space in infancy, albeit not necessarily one with directionality (de Hevia & Spelke, 2010; de Hevia, Vanderslice, & Spelke, 2012; Lourenco & Longo, 2010; see de Hevia, Girelli, & Macchi-Cassia, 2012, for a review.)

A final question of interest is that of the generality of this bias. Insofar as there is a tendency to scaffold even non-numerical information onto a spatial continuum, does it extend to any sort of information to be processed or is it only found for those stimulus dimensions having a clear ordinal structure? One can conceive of different levels of specificity in this process of learning from certain types of spatial structure, ranging from a focused link between number and space (as found by Opfer et al., 2010, Opfer & Furlong, 2011 in children), to a link between well-ordered concepts and space, to a generic processing “boost” for any information (ordinal, or not) presented in a spatially-beneficial manner. The vast majority of research done on SNARC and SNARC-like effects in both children and adults has studied the presence of these links, but not the ramifications for learning and memory- something we aim to accomplish with this set of experiments.

In Experiment 1, English-speaking American and Hebrew-speaking Israeli, preschoolers were given a spatial search task in which non-numerical labels were mapped to locations in either a left-to-right or right-to-left direction. Experiment 2 explores the strength of this link between spatial layout of labels and subsequent memory for this information by changing the nature of the stimulus from traditionally-ordered stimuli (letters) to non-ordered stimuli (color terms), with an American population. Although these children have not started reading, they have already been exposed to strong directional orientations in many non-numerical interactions with parents, other adults and older children (such as being read to or co-viewing a movie; McCrink, Birdsall, & Caldera, 2011). Therefore, we predict that these strong spatial associations will enhance learning even when non-numerical items are presented in a left-to-right direction to English-speaking American children, or right-to-left direction to Hebrew-speaking Israeli children. We also predict that children’s response times will be shorter for conditions that are culturally-congruent. Further, we predict children will adapt more readily to the task and exhibit a steeper learning curve and better performance as the trials progress in culturally-congruent conditions. Finally, we predict that if the benefit of culturally-consistent structuring is found mainly during encoding of the labels (as found by Opfer & Furlong, 2011), performance will be better in those conditions in which initial labeling is culturally-consistent.

1. Experiment 1: Alphabet-Space Relations in American and Israeli Children

1.1. Method

1.1.1. Participants

American participants were 48 children (xx girls; mean age = 48 months, range 36–60 months) recruited in the New York City area through mailings, word of mouth and at local preschools and museums. Socioeconomic level was mixed but mostly xxxx. An additional 17 participants were excluded due to experimenter error (3), refusal to complete task (6), or inability to learn the labels. Israeli participants were 48 3–4-year-olds (m = 45 months, range 34–58 months), recruited in Petach-Tikve, Kefar-Saba and Raanana, through word of mouth and at local preschools. An additional 9 participants were excluded due to experimenter error (2), refusal to complete task (4), or inability to learn the labels (3). We did not include children who were fluent in a language that had opposing directionality to the main language of the country, as assessed by parental report (e.g., Hebrew, Arabic, Farsi for the American children, or English, Russian, French for the Israeli children).

1.1.2. Stimuli

The stimuli consisted of two boxes, the sample box and the matching box. The boxes were both 51cm L × 14cm W × 11cm D and comprised five compartments measuring 9.5cm L × 14cm W × 11cm D. Each compartment had a picture of a common object (balloons, flower, ice cream, basketball, and keys) on its lid. The pictures on the compartments were in the same order for all children, both in the sample box, and the matching box (see Figure 1). The purpose of this visual tagging was to induce variability in children’s performance and provide them with a competing (incorrect) strategy to employ during testing. Although Opfer and colleagues used a seven-compartment box, our piloting revealed that our participants had great difficulty learning seven nonnumerical labels in all conditions (regardless of direction). Since our focus is on the effects of spatial mapping on memory, and not on memory for numbers vs. non-numbers, or overall ease of applying different label types, we decreased the number of compartments.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the match-to-sample paradigm used in the study. Shown here is the LR/RL condition of Experiment 1, in which the sample was labeled left-to-right with the first five letters of the alphabet, and the matching boxes were labeled right-to-left with the same five letters.

1.1.3. Procedure

Each child participated in a spatial search task presented as a game of hide-and-seek with two monkeys. Two boxes were positioned in front of the children such that the sample box was to the left of the child with the final compartment ending at his/her midsection, while the matching box was to the right of the child with the initial compartment beginning at his/her midsection. During testing, the compartments were verbally labeled using the letters A, B, C, D & E (e.g., “This is the ‘A’ box”), and the experimenter performed this labeling until the child was able to repeat it once successfully. The same labeling procedure was used to label the compartments in the matching box. Children who became frustrated and/or did not learn to correctly label the boxes were excluded from the study (11 children).

Once participants were able to correctly label the compartments in both boxes, they were introduced to two monkeys who like to play hide-and-seek. The experimenter explained that one monkey liked to hide in the matching boxes, and the other monkey liked to show people in the sample boxes where his friend could be found. The children were then given an example: “If this monkey shows you his friend is in the A box over here (move monkey around over the sample boxes), then his friend will be in the A box over here (move monkey over the matching boxes).” To ensure the child understood, they were asked, “If the monkey shows you his friend is in the B box over here (gesture toward sample boxes), where will you be able to find the monkey in these boxes (gesture toward matching boxes)?” The children verbally answered this trial and if they answered incorrectly, the question was rephrased and repeated. If the child pointed, they were asked for an explicit verbal answer (“Can you say where the monkey will be?”). Testing began once the children demonstrated that they understood the instructions. Each child participated in the search task five times, finding the monkey in each location once. The order of presentation was counterbalanced such that, on each trial, the monkey was equally likely to be hidden in each unused compartment (a 1 in 5 chance of the A box to start the sequence, then if A is first used, a 1 in 4 chance of the B, C, D, or E box, then if B is used, a 1 in 3 chance of the C, D, or E box, and so on).

1.1.4. Design

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: 1) LR/LR, in which the compartments in both the sample and matching boxes were labeled from left to right, 2) LR/RL, in which compartments in the sample box were labeled from left to right, and those in the matching box labeled from right to left, 3) RL/LR, in which the compartments in the sample box were labeled from right to left and those in the matching box labeled from left to right, and 4) RL/RL, in which compartments in both boxes were labeled from right to left.

This four-cell design is modeled after Opfer and Furlong’s (2011) task design, in which they examined whether the ease of spatially linking the labels to the boxes was due to a spatial left-right bias at encoding or performance. If children perform best on a particular type of sample box directionality (irrespective of matching box directionality), the main spatial bias is present at encoding of initial location. For example, children in LR/LR and LR/RL conditions – who learn the labels A→B→C→D→E on the sample box – may have a strong internal mapping of the monkey to the second label in the sequence, and can readily deploy this mapping when they need to produce the behavior of searching in the second-labeled compartment when matching. However, if children do best on a p0articular type of matching box directionality (irrespective of sample box directionality), it can be concluded that the spatial bias arises mainly during the child’s active performance when matching spatial locations.

1.2. Results

Children were given scores in the form of percentage of (1) label matches, in which the children accurately used the verbal labels between the sample and matching box, (2) perceptual matches, in which the children ignored the labels and simply searched by matching the pictures on the compartments, (3) opposite endmatches, in which children searched for the monkey in the opposite end of the correct location, and (4) random, in which no discernable search pattern was found. For example, a child who made three label matches and two perceptual matches would be scored as 60% letter, 40% perceptual, 0% opposite end and 0% random. The time to choose correctly (latency; coded as the time between the end of the experimenter’s request for a search and the time to a child’s point or first touch of the box) was also noted for each trial.

1.2.1. American Sample

A 4 (score type: label match, perceptual match, opposite end, and random match scores) × 4 (condition: LR/LR, LR/RL, RL/LR, RL/RL) × 2 (gender: male, female) × 2 (age: 3-year-old, 4-year-old) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no significant overall effect of gender or age; thus these variables are not considered further. A significant main effect of score type was found, F(3,132)=9.69, p<.001, partial η2 = .18; pairwise-comparisons (Bonferonni-corrected for multiple comparisons) reveal this was due to children choosing an opposite end strategy (9%) less frequently overall than any of the other strategies (perceptual strategy, 29%; random strategy, 23%, label match strategy, 38%). There was no main effect of condition, but there was a significant interaction of strategy choice with condition, F(9,132)=2.38, p=.02, partial η2 = .14, indicating that children favored different strategies in different conditions.

As predicted, American children exhibited more label matches when information was presented in a left-to-right manner (LR/LR) compared to a right-to-left manner (RL/RL). Performance for label matches in LR/LR was 63% (SE=10.1) but only 28% for RL/RL (SE=7.2), one-tailed t(22)=2.83, p=.005, d = 1.2. Additionally, the latency scores for the LR/LR condition were marginally shorter than those for the RL/RL condition (6.9 sec vs. 10.2), F(1, 21)=3.73, p=.07, d = .80. Although children in LR/LR and RL/RL did not significantly differ in their deployment of opposite end (7% vs. 12%) or perceptual (23% vs. 27%) strategies, children were more likely to choose randomly if they were in the RL/RL condition than the LR/LR condition (32% vs. 7%), t(22) = −3.1, p<.01, d = −1.32. To examine whether children optimized their strategy choice across trials, as found by Opfer et al. (2010, 2011), we performed a 2 (condition; LR/LR vs. RL/RL) X 5 (Trials 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) repeated-measures ANOVA over label matching performance. There was the expected overall main effect of condition, F(1,22)=7.67, p=.01, partial η2 = .26, but no overall increasing linear trend to use label matching as the experiment progressed and no interaction of label matching across trials with condition.

Finally, given that Opfer and Furlong (2011) showed encoding as the primary process in which directionality influenced memory for labels, we predicted that American children would exhibit a higher percentage of label matches when given a sample box that was labeled in a left-to-right manner (the LR/LR and LR/RL conditions, collapsed). However, a one-way ANOVA over percentage of label matches with encoding condition (LR vs. RL) revealed no significant difference between left-to-right (46%) and right-to-left (31%) label matching, F(1, 46)=2.7, p=.11, and no change in latency as a function of encoding condition.

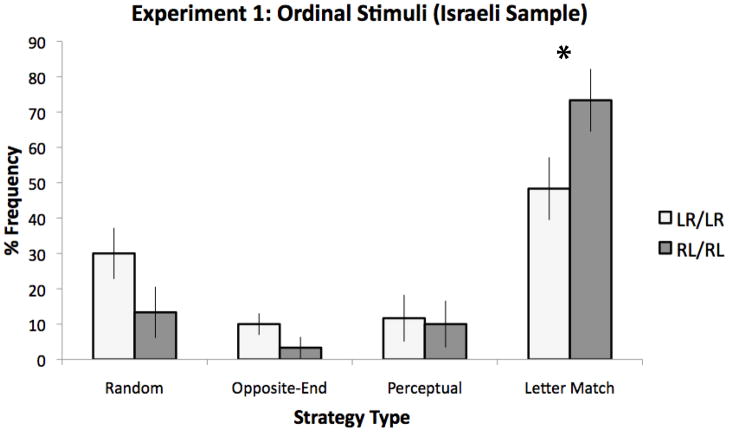

1.2.2. Israeli Sample

A 4 (score type: label match, perceptual match, opposite end, and random match scores) × 4 (condition: LR/LR, LR/RL, RL/LR, RL/RL) × 2 (gender: male, female) × 2 (age: 3-year-old, 4-year-old) repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant overall effect of gender; this variable is not included in further analyses. No significant main effect of age was found, but age did interact with score type, F(3,120)=3.38, p=.02, partial η2 = .08; younger children were less likely to use a label match strategy (48% vs. 4-year-olds’ 71%) and were slightly more likely to use the other strategies. There was a significant main effect of score type; pairwise-comparisons (Bonferonni-corrected for multiple comparisons) reveal this was due to children choosing a label match strategy (59%) more frequently than any other strategies (perceptual match, 15%; opposite end, 6%; random, 20%). Although there was no main effect of condition, there was a marginally significant interaction of strategy choice with condition, (F(9, 132)=1.77, p=.08, partial η2 = .11, suggesting that children chose different strategies in different conditions.

As predicted, Israeli children exhibited more label matches when the information was presented in a right-to-left manner (RL/RL) compared to a left-to-right manner (LR/LR). Performance for label matches in RL/RL was 73% (SE=8.6) but only 48% for LR/LR (SE=10.6), one-tailed t(22) = −1.83, p=.04, d = −.78. However, in contrast to the American sample, the latency scores for the culturally-congruent RL/RL condition were not shorter than those for the LR/LR condition (6.25 sec vs. 6.33), one-way ANOVA over latency with condition as the factor, F(1, 22)=.003, p=.96. Children in RL/RL and LR/LR did not significantly differ in their deployment of opposite end (3% vs. 10% respectively), perceptual (10% vs. 12%), or random strategies (13% vs. 30%; one-tailed t-tests all ps>.05). A 2 (condition; LR/LR vs. RL/RL) X 5 (Trials 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) repeated-measures ANOVA, to test for the presence of the optimal label matching strategy as the experiment progressed, showed a marginal main effect of condition, F(1,22)=3.35, p=.08, partial η2 =.13, with participants more likely to label match in RL/RL trials than LR/LR. Although there was no overall main effect of trial sequence or interaction with condition, unlike the American group, the Israeli children did show a linear trend to increasingly use label matching as the experiment progressed that is independent from condition (from ~54% at T1 to ~71% at T5); F(1,22)=4.64, p=.042, partial η2 = .17.

Finally, we examined whether Israeli children exhibited a higher percentage of label matches when given a sample box labeled in a right-to-left manner (RL/RL and RL/LR conditions) as opposed to a left-to-right manner (LR/RL and LR/LR). A one-way ANOVA of percentage of label matches by encoding condition (LR vs. RL) revealed no significant difference between right-to-left (61%) and left-to-right (48%) label matching, F(1, 46)=2.04, p=.16, and no change in latency as a result of encoding condition.

1.2.3. American-Israeli Comparisons

In order to more directly compare American and Israeli performance, we entered the data from both groups into a univariate ANOVA with label match scores as the dependent variable and condition (LR/LR, LR/RL, RL/LR, RL/RL), gender (boy, girl), age (three-year-old, four-year-old), and ethnicity (American, Israeli) as between-subject factors. There were no effects of gender or age. Although there were no overall main effects of condition or ethnicity, there was an interaction between condition and ethnicity, F(3,88)=3.84, p=.01, partial η2 = .11. American children showed a significantly higher label matching score in the LR/LR condition (63%) compared to the RL/RL condition (28%; p=.035, d = 1.15), and LR/RL condition (28%; p=.035, d = 1.2), and marginally higher than the RL/LR condition (33%; p=.10, d = .86). The Israeli children showed significantly or marginally significant higher label matching scores in the RL/RL condition (73%) with comparable letter-matching scores in LR/LR (48%, p=.06, d = .76), LR/RL(47%, p=.046, d = .86) and RL/LR (48%; p=.06, d = .87). A similar univariate ANOVA was conducted with latency as the dependent variable: there was no effect of condition, a marginal effect of ethnicity, F(1,43)=2.1, p=.06, partial η2 = .08; American children (8.5 sec) took slightly longer overall than Israeli children (6.3 sec), with no interaction between condition and ethnicity.

1.3. Discussion

American preschoolers who heard and saw letter labels for compartments presented in a left-to-right fashion were better able to use these labels to complete a matching task, while Israeli preschoolers exhibited the opposite tendency, showing increased usage of the correct strategy when presented with right-to-left spatial structuring. The American children did not optimize their strategy choice as the experiment progressed although there is a marginal trend in this direction in the Israeli population); neither population showed better optimization for trials that were structured in a culturally-consistent manner. As found by Opfer et al. (2011), American children showed a (marginally) shorter latency of response for the LR/LR condition, although the Israeli children showed equally low latency measures for both conditions. These results suggest that the spatial structuring benefit found for culturally-consistent numerical labeling (Opfer et al., 2010, 2011) is not specific to the particular domain of numbers, although the different findings on response latency and strategy optimization point to a lessening of this benefit with non-numerical stimuli.

Four-year-old Israeli children were more likely to use a letter-matching strategy than younger Israeli children or either age group of American children. This difference likely reflects better non-cognitive skills and/or more letter knowledge on the part of the older Israeli children relative to the younger Israelis or either American age group (whose overall propensity to label match was comparatively low at both ages). These 4-year-old Israelis attend a preschool considered a preparatory program for kindergarten. Kindergarten in Israel is mandatory starting at age 5. Preschool education is less formal in the US. Thus the Israeli 4-year-olds likely had more experience ordering the alphabet and were more practiced in following teachers’ directions.

The label type used in Experiment 1, letters in the order of the alphabet, while not numerical, is highly ordinal, and their order is well rehearsed (children learn the alphabet from infancy, it appears on children’s toys, there is a common song that teaches it). Letters are also commonly paired with numbers on children’s toys. Additionally, in Hebrew, the letter ‘aleph’ is used to also mean ‘one’ in some contexts, ‘bet’ to mean 2, and so forth- a fact that some researchers have used to investigate the semantic encoding and SNARC-like effects prompted by these formats (Razpurker-Apfeld & Koriat, 2006). Indeed, given the connection between letters and numbers, we would expect children to perform similarly on this task using any well-ordered sequence that was practiced and highly associated with numbers (such as months of the year, days of the week). Therefore, an outstanding question is whether the task benefit from spatial structuring is only found when dealing with highly-ordinal (or well-ordered) stimuli, especially when the stimuli are letters (as in this study) and numbers (Opfer et al., 2010, Opfer & Furlong, 2011). It is possible that participants only scaffold information onto space when it is in a digestible and familiar format, or a format readily turned into numerical coding. Alternatively, this tendency to better perform when structure is presented in a culturally-consistent manner might be global and not specific to the type of incoming information. To examine this question, we tested an additional sample of American children, using color terms as labels instead of letters.

Colors are an interesting test case because although they can be ordered on a spectrum (the rainbow, or ROYGBIV- red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet), they are rarely presented in this ordered fashion early in children’s development, as is the alphabet. The potential is there for order but it is not enculturated to the same degree. Since our question pertains to the relative influence of the type of information presented (ordered versus non-ordered), and not on the impact of cultural factors, we only tested an American population. Because there were no differentiating effects of encoding vs. performance in Experiment 1, we eliminated the mixed LR/RL and RL/LR spatial structure types, and presented only uniformly LR or uniformly RL labels. If culturally-consistent spatial structuring helps children to better perform on a matching task, regardless of high ordinality of stimulus type, results should be similar to those found in Experiment 1. If, however, a high degree of ordinality is required to induce a spatial benefit from cultural structuring, no differences should appear between the LR and RL structure types on measures of performance, latency, or response optimization.

2. Experiment 2: Color-Space Relations in American Children

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

Participants were 48 American children (xx girls; mean age = 48 months, range 36–62 months) recruited in the same manner as in Study 1. An additional 30 participants were excluded1, due to experimenter error (5), refusal to complete task (5), or inability to learn the labels (20; 8 in the LR/LR, 12 in the RL/RL condition). We did not include in our sample any children who were fluent in a language that had opposing directionality to the main language of the country, as assessed by parental report (e.g., Hebrew, Arabic, or Farsi).

2.1.2. Stimuli

The stimuli were identical to those used in Experiment 1, with the exception that the panels on each compartment were no longer colored pictures of objects. In order to avoid confusion with color labels for objects that were already colored, we used a set of black-outlined uncolored shapes (for the sample box, left-to-right: triangle, diamond, hexagon, star, circle; for the matching box, left-to-right: star, hexagon, triangle, circle, diamond).

2.1.3. Design and Procedure

For children in the replication condition (n = 24), the procedure was identical to Experiment 1. For children in the color-term condition (n = 24), the procedure was identical with the exception of the label names used. Instead of the letters A through E, we substituted the color terms Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, and Blue. Half of the children in each condition saw both the sample and matching boxes labeled in a left-to-right manner, and half saw them both labeled in a right-to-left manner.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Replication Condition

A 4 (score type: label match, perceptual match, opposite end, and random match scores) × 2 (spatial structure type: LR/LR, RL/RL) × 2 (gender: male, female) × 2 (age: 3-year-old, 4-year-old) repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant overall effects of or interactions involving gender or age; thus these variables were not included in further analyses. A significant main effect of score type was found, F (3,66) = 11.34, p < .001, partial η2 = .34; pairwise-comparisons Bonferonni-corrected for multiple comparisons reveal this was due to tendency for children to choose a spatial, or label match, strategy (46%) more frequently than a perceptual strategy (13%) or opposite end strategy (12%), but not a random strategy (29%). There was no main effect of spatial structure type, but there was a significant interaction of strategy choice with spatial structure, F(3,66)=4.08, p=.01, partial η2 = .16, indicating that children favored different strategies in differing spatial presentations.

As predicted, these American children exhibited more label matches when information was presented in a left-to-right manner (LR/LR) than in a right-to-left manner (RL/RL). Performance for label matches in LR/LR was 65% (SE=8.8) but only 35% for RL/RL (SE=8.8), t(22)=2.43, p=.02, d = 1.04). As in Experiment 1, latency scores for the LR/LR condition were marginally shorter than those for the RL/RL condition, 3.6 vs. 6.4, F(1, 22)=4.16, p=.06, d = −.83. Children in LR/LR and RL/RL also differed in their deployment of a perceptual strategy - 7% vs. 25%; t(22)= −2.2, p=.04, d = −.94, but exhibited similar opposite end (8% vs. 13%) and random (20% vs. 27%) strategy use. To examine whether children optimized their strategy choice across, we performed a 2 (spatial structure type; LR/LR vs. RL/RL) X 5 (Trials 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) repeated-measures ANOVA over label matching performance. There was the expected overall main effect of spatial structure type, F(1,22)=5.88, p=.02, partial η2 = .21, and no overall increasing linear trend to use a label matching strategy as the experiment progressed. In contrast to Experiment 1, there was an interaction of label matching performance across trials with spatial structure type, F(4,88) = 3.89, p < .01, partial η2 = .15, indicating different performance profiles as the experiment progressed. Children who saw LR structure trials progressed from 50% -> 50% -> 75% -> 92% -> 58% across trials, a general upward trend (albeit one with a large drop at the end, perhaps due to fatigue or disinterest). Performance in the RL structure trials oscillated - 33% -> 58% -> 25% -> 17% -> 42%.

2.2.2. Color-term condition

A 4 (score type: label match, perceptual match, opposite end, and random match scores) × 2 (spatial structure type: LR/LR, RL/RL) × 2 (gender: male, female) × 2 (age: 3-year-old, 4-year-old) repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant overall effects of or interactions involving gender or age; thus these variables were not included in further analyses. A significant main effect of score type was found, F (3,66) = 15.72, p < .01, partial η2 = .42; follow-up pairwise-comparisons Bonferonni-corrected for multiple comparisons reveal this was due to children choosing a spatial, or label match, strategy (46%) more frequently overall than a perceptual strategy (11%) or opposite end strategy (3%), but not a random strategy (39%). There was no main effect of spatial structure type, and, in contrast to previous experiments, no interaction of strategy choice with spatial structure type, F(3,66)=1.59, p=.20, indicating that children who had to use these non-ordinal color terms did not favor different strategies in different spatial structure types (50% label-match in LR, 42% in RL). Furthermore, t-tests comparing each strategy usage percentage in LR and RL structure types were all nonsignificant.

Latency scores for the LR/LR spatial structure type were significantly shorter than those for the RL/RL spatial structure type - 5.4 vs. 10.1, F(1, 22)=7.08, p=.01, d = −1.08. To examine whether children optimized their strategy choice across trials, we performed a 2 (spatial structure type; LR/LR vs. RL/RL) X 5 (Trials 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) repeated-measures ANOVA over label matching performance. There was no overall main effect of spatial structure type, no overall increasing linear trend to use label matching as the experiment progressed, and no interaction of label matching performance across trials with spatial structure type.

To directly compare replication and color-term conditions, we performed a 4 (strategy type: label matching, perceptual, opposite, or random) × 2 (spatial structure type: LR, RL) × 2 (condition: replication, color-term) omnibus repeated-measures ANOVA. There was a significant main effect of strategy type, F(3,132)=24.94, p<.001, partial η2 = .36, a significant interaction of strategy type with spatial structure type, F(3,132)=3.43, p=.02, partial η2 = .07, a marginal interaction of strategy type with condition, F(3,132)=2.34, p=.07, partial η2 = .05, and a marginal interaction of strategy type, spatial structure type, and condition, F(3,132)=2.14, p=.09, partial η2 = .05. Post-hoc comparisons illustrate that, overall, the children used a label match or random strategy similarly (48% and 32%), and more often than either a perceptual (14%) or opposite end (6%) strategy. In LR structure types children showed higher label matching performance (58%) relative to other types of strategies (12% perceptual, 6% opposite end, and 25% random). In RL structure types children showed similar label matching strategy (38%) and random strategy (38%) use, with perceptual strategy at 17% and opposite end strategy at 7%. Children in the replication condition, across the spatial structure types, showed a greater degree of label matching (50%) relative to the other strategies, while children in the color-term condition showed similar amounts of label-matching and random guessing (46% and 40%, respectively). Finally, as the three-way interaction between strategy type, spatial structure type, and condition suggests, the amount of label-matching strategy in the replication condition was quite high when the spatial structure was LR (65%), and the disparity between this strategy and the second most-common strategy (random answering) was starkest in this particular cell (a delta of 45%).

2.3 Discussion

Experiment 2 replicates the finding from Experiment 1 that American preschoolers perform better on a matching task when given ordinal information that is spatially presented in a culturally-consistent way. Children who learned alphabetical labels presented in a left-to-right manner were more likely to use a successful label-matching strategy compared to those who learned these labels in a right-to-left manner. They also selectively optimized their performance as the experiment progressed in the left-to-right spatial structure type, with the tendency to employ the correct strategy generally rising as the experiment progressed. This spatial presentation matching benefit does not appear to extend to scenarios in which the to-be-mapped labels are not commonly learned in a well-practiced, ordered way, i.e., color terms instead of alphabetical labels. Children who heard the labels “red-orange-yellow-green-blue” mapped to spatial locations showed equivalent amounts of successful spatial strategy use, regardless of the incoming spatial structure of the information (left-to-right, or right-to-left). However, they did respond more quickly when the labels were presented from left-to-right, perhaps reflective of a higher degree of comfort or familiarity with culturally-consistent information.

3. General Discussion

The goal of our study was threefold. First, we wished to examine whether the reading directionality of the surrounding culture affected spatial encoding prior to formal schooling or extensive self-directed reading experience (3–5 years of age). Second, we wanted to determine if this impact was specific to a spatial-numerical interface, or whether it reflected a more general stance to map well-ordered sequences to a spatial continuum. Third, we explored whether this stance extended even beyond the domain of traditionally-ordered stimuli (e.g., numbers and letters) into a well-known but relatively unordered domain (color names).

Our results indicate that the cultural milieu of the child does indeed impact ability to absorb information when it is presented spatially. American children were much more likely to use a successful labeling strategy when they were presented information in a manner that was consistent with the left-to-right pattern of English, whereas Israeli children were more likely to excel when presented with labels that were consistent with the right-to-left pattern of Hebrew.

This alignment of the directionality of language and the ability to take in information challenges the theory that there is an innate preference for left-to-right spatial attention to objects. Furthermore, this directional bias was present in an ordered, but non-numerical, set of stimuli (the first five letters of the alphabet). American children also exhibited increased speed in performing the task when it was presented in a culturally-consistent fashion, with faster latency to choose the correct match when the labeling occurred from left to right. We replicated the initial finding in an American population and found that English-speaking children do not show this same learning bias for culturally-consistent spatial structuring if the to-be-learned stimuli are not highly ordinal. Their preschool age is the earliest known age at which evidence has been found for a culturally-specific, coordinated mapping between non-numerical sequences and spatial continua, a phenomenon documented in the adult literature (Prado et al., 2008; Previtali et al., 2010) and reflecting a (limited) tendency for an organism to recruit order from one cognitive domain to scaffold memory or attention in a different ordered domain.

The present findings are consistent with those of Opfer et al. (2010, 2011), with American children performing more quickly and accurately when the labeling occurred from left-to-right. However, some key differences are seen in performance. First, the children in our study generally struggled to learn the seven-label version that was used in Opfer et al. (2010, 2011), and it wasn’t until we reduced the number of compartments that the majority of children could reliably repeat our labels. Second, the nature of the alternate strategies used in the numerical vs. non-numerical labeling task differed. Opfer and Furlong (2011) found that children in the RL/RL condition made relatively frequent opposite end errors, indicating that they were trying to impose a left-to-right system on the input and production process. Our Experiment 1 and replication condition data, however, indicate that American children who received right-to-left mappings were more likely to choose randomly than were those who received left-to-right mappings. Third, children in the Opfer et al. (2010) study showed improvement from trial to trial, and this improvement was specific to the culturally-congruent, left-to-right condition. We observed mixed adaptive strategy use for our American sample. It was not present in Experiment 1, but present in the letter-label condition of Experiment 2, although Israeli children did show some improvement with regard to strategy use, it was not specific to the culturally-congruent, right-to-left condition. These differences suggest that, although we find here a tendency to link non-numerical ordered sequences to a spatial continuum, there does not appear to be the same ease, motivation, or intuitiveness as is seen specifically in the case of numbers and space.

The mapping process employed appears to be relatively accepting of different types of stimuli, if these stimuli are conceptualized as ordinal by the children (as shown by similar performance for the LR and RL conditions when learning non-ordinal color term labels in Experiment 2). It is also culturally-specific, with the surrounding language determining the directionality of the mapping. In this way, it mirrors the classic SNARC effect for spatial-numerical links. One outstanding question is whether the non-numerical spatial mapping we observed in Experiment 1 occurs out of exposure to an ordered count list, which in turn prompts a tendency to apply numerical techniques to non-numerical stimuli. This interpretation is compatible with the finding by Opfer et al. (2011) that consistent directional counting from left to right mediated preschoolers’ increased performance during the left-to-right condition of the match-to-sample box task.

Alternatively, it is possible that a general bias to distribute attention in a culturally-specific way arises from caregivers reading, pointing, and interacting in a directional manner, and this pattern of results is found in addition to (and not because of) spatial-numerical mapping tendencies. The relation between counting and spatial-numeric associations is potentially more complex than early counting practice leading to the development of spatial-numeric associations; counting and spatial-numeric associations may share some other common origin that extends beyond numbers.

Some limitations of our study are relevant here. First, there was no quantification task given to the children to assess whether they reliably counted, added, and subtracted in a spatially-consistent manner (as in Opfer et al., 2010). Similarly, we did not obtain a measure of finger counting by the children, another likely indicator of the strength and nature of their spatial-numerical mappings (Lindemann, Alipour, & Fischer, 2011). These types of tasks potentially provide insight into whether the numerical spatial structuring is necessary for, or related to, appearance of these biases in other stimulus domains. Shaki et al. (2012) found spatial-numerical mappings in an Israeli preschooler population but also observed that these mappings lessened over time as children entered the school system and were exposed to numbers (but not text) that were read from left to right. Such findings pit reading experience against mathematics experience and provide a promising avenue to explore whether changing directionality with schooling in a numerical domain has the subsequent impact on a non-numerical domain that the former account predicts. Shaki, Fischer, and Petrusic (2009) found that this conflict appears for adult Hebrew-speakers, who show no standard SNARC effect- likely because Hebrew text is read from right to left, but numbers are plotted from left to right.)

It is surprising that neither sample in Experiment 1 showed better performance in the culturally-incongruent conditions than in the mixed conditions. One would imagine that having a consistent spatial layout, even if it’s not in a culturally-palatable direction, would be beneficial relative to having to recall a flip in labeling between the sample and match compartments. This does not seem to be the case here. For both Americans and Israelis, having any culturally-inconsistent information (whether it be at encoding or recall) seemed to lead to relatively poor performance when learning an ordered stimulus set. This interpretation is consistent with the fact that, unlike Opfer and Furlong (2011), we did not find a strategy advantage for those conditions in which the specific process of encoding the initial sample box was culturally congruent. Whether the culturally relevant mapping occurs at encoding or performance didn’t matter; having this ‘bad’ kind of directionality at either point in the first experiment decreased performance relative to not having it at all.

American children who participated in the replication condition of Experiment 2, (which used slightly-different perceptual stimuli on the compartments of shapes instead of pictures) exhibited the same learning bias and increased performance efficiency (latency of choice) for culturally-consistent, i.e. LR, structuring as those in Experiment 1. Additionally, they improved across trials, with more adaptive strategy use as the experiment progressed – for LR structure. Two important findings come from the color-term condition in Experiment 2. First, we saw no evidence for better learning or adaptive strategy use when the to-be-learned stimuli were not of a traditionally-ordinal nature. This suggests that, for children at least, a culturally-influenced spatial structure is either selectively – or perhaps effectively - recruited in instances that are specifically coded as ordinal by the learner (as is the case with the count list and the alphabet). The second finding worth noting is that children who had to label match using color terms did show a latency effect. They were faster to choose in the LR conditions than the RL conditions- even if they did not necessarily use a successful label-matching strategy differentially. A possible interpretation of this pattern of results is that children were exhibiting (unwarranted) confidence when learning in a familiar cultural structure (LR), even if this confidence did not necessarily affect performance. The latency effect with non-ordinal labels suggests that there still is an indirect benefit of learning when information is presented in a culturally consistent manner, even for non-ordinal items. We are currently exploring whether, and at what point in development, this comfort with learning generic information in a culturally-consistent fashion translates to a learning benefit.

These findings provide a case study as to how the developing mind capitalizes on an intuitive propensity to scaffold one domain onto another – within limits - and shapes this tendency in concert with the sociocultural environment of the child. What we observed here, alongside other findings on cultural influences on spatial cognition, allows us to conclude that although the impact of language and culture is subtle, it has ramifications for very general processes that in turn influence how one learns and thinks in everyday situations. This study attempts to illuminate the impact of culture and language on foundational aspects of schooling and education by exploring the way that very young children attend to their environment, recall facts and sequences about particular types of learning materials, and choose adaptive strategies.

Figure 2.

Data for the American sample in the LR/LR and RL/RL conditions of Experiment 1, indicating the percentage of time each strategy type was chosen by the children. Asterisks indicate significance with an alpha level of .05.

Figure 3.

Data for the Israeli sample in the LR/LR and RL/RL conditions of Experiment 1, indicating the percentage of time each strategy type was chosen by the children. Asterisks indicate significance with an alpha level of .05.

Figure 4.

Data for the American children in Experiment 2, with letters (ordinal stimuli) and color-terms (non-ordinal stimuli) as label types. Indicated here is the percentage of time the spatial-match strategy type was employed by the children in the LR/LR and RL/RL spatial structure type. Asterisks indicate significance with an alpha level of .05.

Highlights.

We test preschoolers who are exposed to different languages in a spatial search task.

We examine whether learning ordinal and non-ordinal information in a manner consistent with their culture enhanced learning and memory of labels.

Preschoolers link ordinal but not non-ordinal - information with space before the onset of self-directed reading.

This link is modulated by the reading directionality of the preschoolers’ cultures.

Footnotes

This higher number of children excluded is a result of a change in research assistants between experiments. In Experiment 2, the assistant was less successful in encouraging children to learn the labels and complete the task. However, the number of children who were excluded was identical across conditions (15 in each).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berch DB, Foley EJ, Hill RJ, Ryan PM. Extracting parity and magnitude from Arabic numerals: Developmental changes in number processing and mental representation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1999;74:286–308. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1999.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroditsky L. Does language shape thought? Mandarin and English speakers’ conceptions of times. Cognitive Psychology. 2001;43:1–22. doi: 10.1006/cogp.2001.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman M. Learning how to structure space for language: A crosslinguistic perspective. In: Bloom P, Peterson MA, Nadel L, Garrett MG, editors. Language and space. Language, speech, and communication. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1996. pp. 385–486. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, Southwood MH, Basilico D. Verbs, events and spatial representations. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:395–402. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY. Do Chinese and English speakers think about time differently? Failure of replicating Boroditsky (2001) Cognition. 2007;104(2):427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Bossini S, Giraux P. The mental representation of parity and number magnitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1993;122:371–396. [Google Scholar]

- de Hevia MD, Girelli L, Macchi-Cassia V. Minds without language represent number through space: Origins of the mental number line. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3(466) doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hevia MD, Vanderslice M, Spelke ES. Cross-Dimensional Mapping of Number, Length and Brightness by Preschool Children. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hevia MD, Spelke ES. Spontaneous mapping of number and space in adults and young children. Cognition. 2009;110(2):198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hevia MD, Spelke ES. Number-space mapping in human infants. Psychological Science. 2010;21:653–660. doi: 10.1177/0956797610366091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLoache JS. Rapid change in the symbolic functioning of very young children. Science. 1987;238:1556–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.2446392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MH. Spatial representations in number processing – evidence from a pointing task. Visual Cognition. 2003;10:493–508. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Shaki S, Cruise A. It Takes Just One Word to Quash a SNARC. Experimental Psychology. 2009;56:361–366. doi: 10.1027/1618-3169.56.5.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furhman O, Boroditsky L. Cross-cultural differences in mental representations of time: Evidence from an implicit nonlinguistic task. CognitiveScience. 2010;34:1430–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2010.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevers W, Reynvoet B, Fias W. The mental representation of ordinal sequences is spatially organized. Cognition. 2003;87:B87–B95. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(02)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevers W, Reynvoet B, Fias W. The mental representation of ordinal sequences is spatially organized: Evidence from days of the week. Cortex: A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior. 2004;40:171–172. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70938-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbel SM, Shaki S, Fischer MH. The cultural number line: A review of cultural and linguistic influences on the development of number processing. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2011;42:543–565. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard EM, Piazza M, Pinel P, Dehaene S. Interactions between number and space in parietal cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:435–448. doi: 10.1038/nrn1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January D, Kako E. Re-evaluating evidence for linguistic relativity: Reply to Boroditsky (2001) Cognition. 2007;104(2):417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber S, Sodian B. Preschool children’s ability to visually represent relations. Developmental Science. 2008;11:390–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson SC. Language and space. Annual Review of Anthropology. 1996;25:353–382. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann O, Alipour A, Fischer M. Finger counting habits in Middle-Eastern and Western individuals: An online survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2011;42:566–578. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein J, Gentner D. Relational language and the development of relational mapping. Cognitive Psychology. 2005;50:315–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco SF, Longo MR. General magnitude representation in human infants. Psychological Science. 2010;21:873–881. doi: 10.1177/0956797610370158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas A, Russo A. Directional bias in the mental representation of spatial events: Nature or culture? Psychological Science. 2003;14:296–301. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.14421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrink K, Birdsall W, Caldera C. Transmission of left-to-right spatial structuring in childhood. Poster session presented at the Seventh Biennial Meeting of the Cognitive Development Society; Philadelphia, PA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough L, Choi S, Mandler JM. Understanding spatial relations: Flexible infants, lexical adults. Cognitive Psychology. 2003;46:229–259. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0285(02)00514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opfer JE, Furlong EE. How numbers bias preschoolers’ spatial search. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2011;42:682–695. [Google Scholar]

- Opfer JE, Thompson CA, Furlong EE. Early development of spatial- numeric associations: Evidence from spatial and quantitative performance of preschoolers. Developmental Science. 2010;13:761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pica P, Lemer C, Izard V, Dehaene S. Exact and approximate arithmetic in an Amazonian indigene group. Science. 2004;306:499–503. doi: 10.1126/science.1102085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado J, Van Der Henst J, Noveck IA. Spatial associations in relational reasoning: Evidence for a SNARC-like effect. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008;61:1143–1150. doi: 10.1080/17470210801954777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali P, de Hevia MD, Girelli L. Placing order in space: The SNARC effect in serial learning. Experimental Brain Research. 2010;301:599–603. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-2063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priftis K, Zorzi M, Meneghello F, Marenzi R, Umilta C. Explicit versus implicit processing of representational space in neglect: Dissociations in accessing the mental number line. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18:680–688. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razpurker-Apfeld I, Koriat A. Flexible mental processes in numerical size judgments: The case of Hebrew letters that are used to convey numbers. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2006;13(1):78–83. doi: 10.3758/bf03193816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugani R, Kelly DM, Szelest I, Regolin L, Vallortigara G. Is it only humans that count from left to right? Biology Letters. 2010;6:290–292. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi E, Kwan B, Giordano BL, Umilta C, Butterworth B. Spatial representation of pitch height: The SMARC effect. Cognition. 2006;99:113–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir E. The status of linguistics as a science. Language. 1929;5:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Shaki S, Fischer MH. Reading space into numbers – a cross-linguistic comparison of the SNARC effect. Cognition. 2008;108:590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaki S, Fischer M, Petrusic W. Reading habits for both words and numbers contribute to the SNARC effect. Psychological Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:328–331. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaki S, Fischer M, Göbel S. Direction counts: A comparative study of spatially directional counting biases in cultures with different reading directions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;112(2):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tverskey B, Kugelmass S, Winter A. Cross-cultural and developmental trends in graphic productions. Cognitive Psychology. 1991;23:515–557. [Google Scholar]

- Whorf BL. Science and Linguistics. In: Carroll JB, editor. Language, thought and reality: Selected writings. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Wood G, Willmes K, Nuerk H-C, Fischer M. On the cognitive link between space and number: A meta-analysis of the SNARC effect. Psychology Science Quarterly. 2008;50:489–525. [Google Scholar]

- Zebian S. Linkages between number concepts, spatial thinking, and directionality of writing: the SNARC effect and the reverse SNARC effect in English and Arabic monoliterates, biliterates, and illiterate Arabic speakers. Journal of Cognition and Culture. 2005;5:165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zorzi M, Priftis K, Umilta C. Brain Damage-Neglect disrupts the mental number line. Nature. 2002;417(6885):138–139. doi: 10.1038/417138a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]