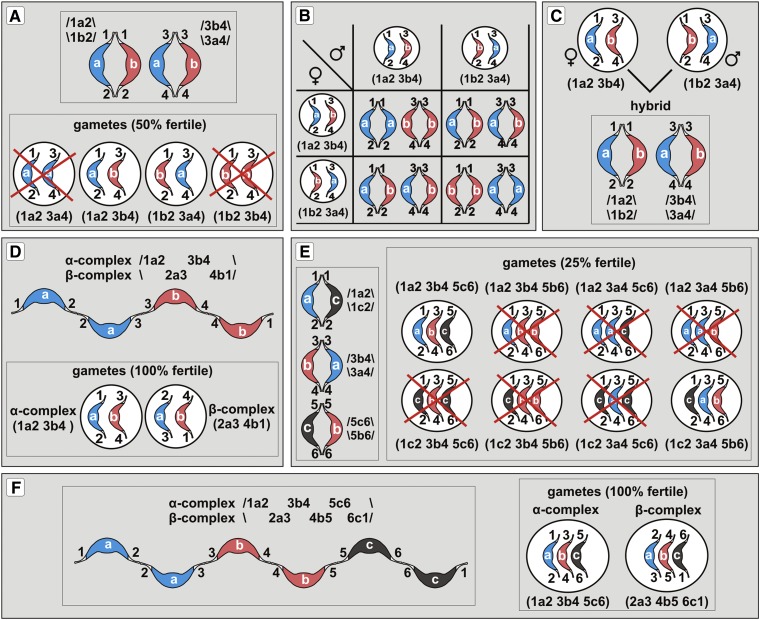

Figure 5.

Evolution of PTH Triggered by Bivalents with Nonhomologous Middle Regions.

(A) Two structurally heterozygous bivalents, 1a2/1b2 and 3a4/3b4, segregating independently (top panel). The presence of such bivalents, however, reduces fertility to 50% (bottom panel). Out of the four possible gametes, two of them (1a2/3a4 and 1b2/3b4) will miss one of the middle regions and thus are genetically unbalanced and lethal. Only the remaining two (1a2/3b4 and 1b2/3a4) contain both middle regions.

(B) Half of the progeny of the fertile gametes from (A) possesses structurally heterozygous bivalents (1a2/1b2 + 3a4/3b4), and the other half is structurally homozygous but splits into two categories: (1a2/1a2 + 3b4/3b4) and (1b2/1b2 + 3a4/3a4).

(C) The two types of homozygous progeny from (B) differ by their chromosomes. Upon hybridization (top panel), they will produce offspring with structurally heterozygous bivalents (1a2/1b2 and 3b4/3a4) again (bottom panel). Structurally heterozygous bivalents can therefore persist in a population.

(D) Since the plants with two structurally heterozygous bivalents have their fertility reduced to 50% (and only half of the viable offspring is true breeding), there is a selection for the fixation of such meiotic configurations in which nonhomologous middle regions are alternately arranged (top panel). Such an arrangement produces only two types of fully fertile gametes (bottom panel) and the offspring is uniform over generations.

(E) and (F) When more than two heterozygous bivalents are present, the fertility is more severely reduced and larger meiotic rings arise as a consequence. For example, three structurally heterozygous bivalents ([E], left panel) reduce gamete fertility to 25% ([E], right panel). However, the alternate arrangement of the chromosomes in a ring ([F], left panel) still produces 100% of the viable gametes ([F], right panel).

For convenience, only chromosomes involved in translocations are shown, and rings are represented as chains.