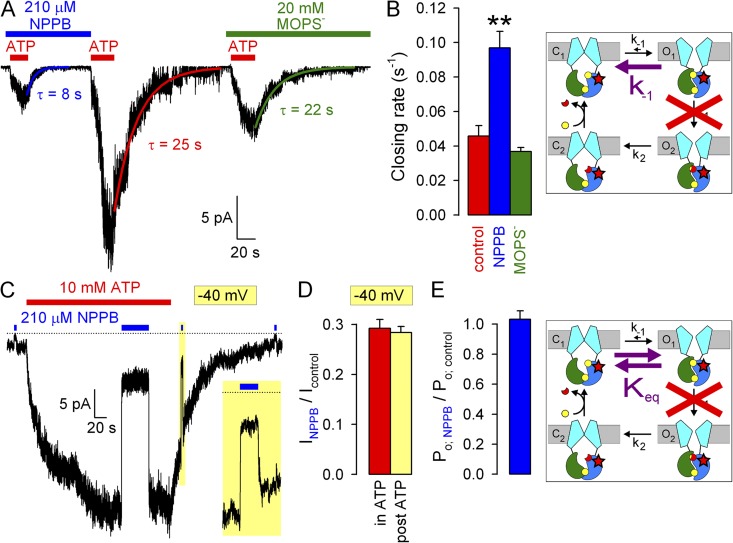

Figure 4.

Effects of NPPB and MOPS− on gating rates under nonhydrolytic conditions. (A) Macroscopic K1250A CFTR current at −120 mV elicited by exposures to 10 mM ATP in the absence or presence of blockers. Colored lines, single-exponential fits (τ, time constants). (B) Macroscopic closing rates (bars, 1/τ) in the absence (red) and presence of NPPB (blue) or MOPS− (green) quantify effects on rate k-1 (cartoon, purple arrow). The K1250A mutation (B and E, cartoons, red stars) disrupts ATP hydrolysis in site 2 (red cross). (C) Macroscopic K1250A CFTR current elicited by 10 mM ATP at −40 mV, prolonged exposure to 210 µM NPPB of channels gating at steady state, and brief exposure to NPPB of surviving locked-open channels after ATP removal (10-s yellow box, expanded in inset). Bracketing brief applications of NPPB to small residual CFTR currents were used to estimate zero-current level (dotted line). (D) Fractional K1250A CFTR currents at −40 mV in 210 µM NPPB applied during steady-state gating (red bar) or in the locked-open state (yellow bar). (E) Effect of NPPB on the closed–open equilibrium (cartoon, purple double arrow). Fractional effect on Po for K1250A CFTR (blue bar) was calculated as in Fig. 2 E.