Abstract

Background

Over 80% of US adults use the Internet; 65% of online adults use social media; and more than 60% use the Internet to find and share health information.

Purpose

State tobacco control campaigns could effectively harness the powerful, inexpensive online messaging opportunities. Characterizing current Internet presence of state-sponsored tobacco control programs is an important first step toward informing such campaigns.

Methods

A research specialist searched the Internet for state-sponsored tobacco control resources and social media presence for each state in 2010 and 2011, to develop a resource inventory and observe change over six months. Data were analyzed and websites coded for interactivity and content between July and October, 2011.

Results

While all states have tobacco control websites, content and interactivity of those sites remain limited. State tobacco control program use of social media appears to be increasing over time.

Conclusion

Information presented on the Internet by state-sponsored tobacco control programs remains modest and limited in interactivity, customization, and search engine optimization. These programs could take advantage of an important opportunity to communicate with the public about the health effects of tobacco use and available community cessation and prevention resources.

Introduction

The Internet has become an important source of information and entertainment. In 2012, 81% of all American adults reported using the Internet; 82% of adult Internet users reported using it daily.1,2 In August 2011, 65% of online adults reported using social networking sites (SNS), more than double the SNS use reported in 2008.3 In August 2013, 80% of all Internet users—59% of American adults—said they searched online for health-related topics.4

State tobacco control programs traditionally have relied on mass media campaigns to deliver antitobacco messages;5–8 mounting fiscal constraints have forced these programs to operate with increasingly fewer resources. The Internet and digital media represent inexpensive new opportunities to disseminate tobacco control messages.

Research has shown that, amid the widely diverse content on the Internet, effective websites share three key characteristics: interactivity, easy access, and relevance. Interactive features drive traffic to a website and improve users’ experience with and preference for that site.9 Interactivity of Internet-based health communication has been shown to positively affect information processing, self-efficacy, and other intermediary factors toward health outcomes.10 Additionally, people consuming health-related information online tend to engage more readily with easily accessible information they perceive as relevant and credible.11

Digital media platforms demand new creativity in message development and dissemination. A growing body of evidence suggests that the tobacco industry already realizes the new media’s potential for product promotion,12,13 and interactive digital communication has become an important marketing tool.14 Yet little is known about the extent to which state tobacco control programs are using new media to promote their messages.

This brief report provides a snapshot of the Internet and social media presence of state tobacco control programs in 2010 and 2011.

Methods

A research specialist at the Institute of Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) systematically searched for each state’s tobacco control resources on the Internet in December 2010, and again in June 2011. Data were analyzed and coded between July and October 2011.

Website Content

Searches employed the Google search engine to find each U.S. state’s department of health website. On finding the website, the researcher then used either the site map or an internal search function to locate the site for the state tobacco control program. The content of each website was profiled across three dimensions: target population, type of site, and level of interactivity. Website target population was defined as General Audience, Adults, or Youth, based on whether the site designated material for specified audiences. Website type was coded as Cessation Assistance if it provided online tobacco cessation services directly to consumers; Cessation Referral if it referred consumers to cessation services such as a quit line; Prevention if it encouraged people to avoid smoking or tobacco products; and Policy if it offered information about state tobacco-related legislation or regulation.

Website interactivity was defined by the extent to which users could interact with other people or elements on each site. Websites were coded Text only if they provided no opportunity for interactive feedback; Interactive Social Networking Sites (SNS) if users could sign up as members and create a login ID and profile; and Interactive Other if they had interactive aspects but no SNS capabilities.

Social Media

Social media information was recorded if it was displayed on the state tobacco control program website. Data were collected for Facebook presence (existence of fan page, number of fans, and page address) and Twitter activity (existence of account, number of followers, and number of people followed).

Results

State Tobacco Program Websites: Content and Interactivity

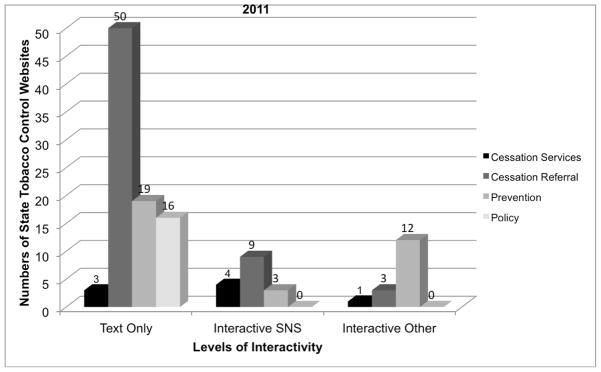

The searches identified tobacco control websites for all states and the District of Columbia in both December 2010 and June 2011. Variety of website content type increased substantially between the two search dates. Figures 1 and 2 show the number of state tobacco control websites presenting each content type, by level of interactivity, at each time point.

Figure 1.

Type and Interactivity of State-Sponsored Tobacco Control Websites, December 2010 Note: SNS, Social Networking Sites

Figure 2.

Type and Interactivity of State-Sponsored Tobacco Control Websites, June 2011 Note: SNS, Social Networking Sites

In December 2010, all 50 states offered cessation referral on their tobacco control websites; 43 presented cessation referral in text-only format, five used interactive SNS format, and two used interactive other. Eighteen websites provided prevention information. Ten states offered webpages coded as having policy content; each of these provided information related to smoke-free air laws, and none addressed other tobacco control policy topics. By June 2011, 12 sites presented cessation referral in an interactive format. Number of sites presenting prevention information had increased to 34, and 16 presented policy information—again, only about smoke-free air laws.

While the overall number of state-sponsored tobacco control websites increased by 46% (from 82 to 120) between December 2010 and June 2011, the extent of interactivity on the sites remained modest over time.

Social Media

State tobacco control programs’ use of social media clearly increased over the period of the study: State tobacco control Facebook presence increased by 180% (from 10 to 28), and state tobacco control Twitter accounts by 475% (from 4 to 23) between December 2010 and June 2011.

Discussion

All state tobacco control programs had some Internet presence; several states offered multiple websites. Most state tobacco control websites were basic, involving text-only content with referral to cessation treatment. Several sites described current smoke-free air policies, but none addressed other tobacco control policy areas. Tobacco control programs may perceive that few readers seek policy information, or policies may be included on other state agency websites. The Internet can provide a vehicle for tobacco control programs to disseminate community resources for cessation and prevention and complement traditional mass media outreach.

While most state tobacco control websites were text only, there were several notable exceptions. Optimization of state tobacco control websites’ interactivity could improve their reach and utility for residents.

This report has limitations. No information was gathered about how many visitors each site attracted, how visitors reacted to information, or extent to which they shared information from the sites with others. The evolving nature of social media means that data gathered at any time point offers only a snapshot of that given moment. Despite the limitations, this research provided the first systematic review of the Internet presence of state-sponsored tobacco control programs. These findings are broadly consistent with the limited body of research on new media in tobacco control and public health. In a review of 68 tobacco control websites identified across five countries, Freeman and Chapman (2012)15 found moderate usage of interactive content and limited integration of social media. Thackeray et al. (2012)16 found that, while 60% of state health departments maintained at least one social media platform, their collective reach was limited and lacked interactivity.

In contrast, there is evidence that the tobacco industry embraces the Internet and social media. The same restrictions on tobacco advertising on TV apply to the Internet; however, few laws or regulations pertain to online tobacco marketing or promotions.17 While the FDA’s 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act requires implementation of the 1996 “final rule” restricting tobacco advertising to black-and-white text only, this rule applies to print advertising with no mention of the Internet.18 State laws to regulate Internet tobacco sales have focused on preventing tax evasion.17 In 2005, over 500 Internet sites sold cigarettes;13 tobacco products are being promoted online.19–21 Without improved data about individuals’ exposure to, seeking, and exchange of both pro- and anti-tobacco information on the Internet and social media, tobacco control programs cannot use these resources to their fullest potential. To reach their audience better and to combat a growing body of pro-tobacco information, state tobacco control programs must enhance their Internet presence and fully embrace interactivity and social media.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (CA123444 and 5U01CA154254) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5U48DP000048-05). The authors would like to acknowledge Tamara Looney for providing Internet search and methodology, and Aimee Humphrey for manuscript editing.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pew Internet & American Life Project. Pew Internet & American Life Project Tracking Survey, February 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Internet Research; 2012. Trend data: Demographics of internet users. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pew Internet & American Life Project. Trend data: Adults. Pew Internet & American Life Project Tracking Survey, February 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Internet Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madden M, Zickuhr K. 65% of online adults use social networking sites. Washington, DC: Pew Internet Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox S, Duggan M. Health Online 2013. Washington, D.C: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs—August 1999. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emery S, Wakefield MA, Terry-McElrath Y, Saffer H, Szczypka G, O’Malley PM, et al. Televised state-sponsored antitobacco advertising and youth smoking beliefs and behavior in the United States, 1999–2000. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(7):639–45. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Cancer Institute. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Jun, 2008. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. NIH Pub. No. 07–6242. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durkin S, Brennan E, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):127–38. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broekhuizen T, Hoffmann A. Interactivity perceptions and online newspaper preference. J Inter Adv [Internet] 2012;12(2) Available from: http://jiad.org. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H, Stout PA. The effects of interactivity on information processing and attitude change: Implications for mental health stigma. Health Comm. 2010;25(2):142–54. doi: 10.1080/10410230903544936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metzger MJ, Flanagin AJ. Using Web 2.0 technologies to enhance evidence-based medical information. J Health Comm. 2011;16(sup1):45–58. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.589881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeman B, Chapman S. British American Tobacco on Facebook: Undermining Article 13 of the Global World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Tob Control. 2010;19(3):e1–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids (CTFK) Internet tobacco sales. 2005 Retrieved January, 17, 2010, from http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/reports/internet/

- 14.Dewhirst T. New directions in tobacco promotion and brand communication. Tob Control. 2009;18(3):161–2. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.029595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman B, Chapman S. Measuring interactivity on tobacco control websites. J Health Commun. 2012;17(7):857–65. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.650827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thackeray R, Neiger BL, Smith AK, Van Wagenen SB. Adoption and use of social media among public health departments. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chriqui JF, Ribisl KM, Wallace RM, Williams RS, O’Connor JC, el Arculli R. A comprehensive review of state laws governing Internet and other delivery sales of cigarettes in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):253–65. doi: 10.1080/14622200701838232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribisl KM. Research gaps related to tobacco product marketing and sales in the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Nicotine & Tob Res. 2012;14(1):43–53. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribisl KM, Lee RE, Henriksen L, Haladjian HH. A content analysis of Web sites promoting smoking culture and lifestyle. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(1):64–78. doi: 10.1177/1090198102239259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribisl KM, Kim AE, Williams RS. Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2007. Sales and marketing of cigarettes on the Internet: Emerging threats to tobacco control and promising policy solutions. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribisl KM. The potential of the internet as a medium to encourage and discourage youth tobacco use. Tob Control. 2003;12(Suppl 1):i48–59. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_1.i48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]