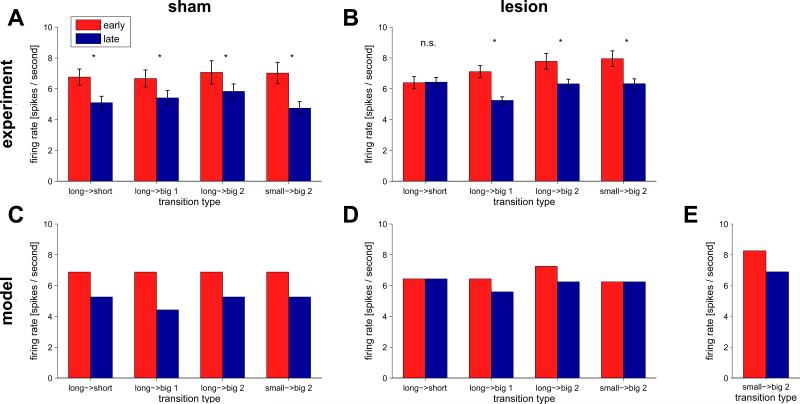

Figure 6.

Firing of dopaminergic VTA neurons at the time of unexpected reward early (first two trials, red) and late (last five trials, blue) in a block. Unlike in Takahashi et al. (2011), where neural responses were averaged over the different types of unexpected reward delivery, here we divided the data into the four different cases, indicated by the green annotations in figure 5A: the short reward after the long to short transition between blocks 1 and 2 (long → short), the arrival of the first (long → big1) and second (long → big2) drops of reward after the long to big transition between blocks 2 and 3, and the second drop of the small to big transition between blocks 3 and 4 (small → big2). (A) Experimental data for sham-lesioned controls (n = 30 neurons). (B) Experimental data for the OFC-lesioned group (n = 50 neurons). (C) Model predictions for the sham-lesioned animals. (D) Model predictions for OFC-lesioned animals. (E) Model predictions for the small to big transition (small → big2) taking into account the variable third drop of juice.