Abstract

CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) play an important role in maintaining host immune tolerance via regulation of the phenotype and function of the innate and adaptive immune cells. Whether allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs can regulate recipient mouse macrophages is unknown. The effect of allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs on recipient mouse resident F4/80+macrophages was investigated using a mouse model in which allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs were adoptively transferred into the peritoneal cavity of host NOD-scid mice. The phenotype and function of the recipient macrophages were then assayed. The peritoneal F4/80+ macrophages in the recipient mice that received the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs expressed significantly higher levels of CD23 and programmed cell death-ligand 1(PD-L1) and lower levels of CD80, CD86, CD40 and MHC II molecules compared to the mice that received either allogeneic CD4+CD25− T cells (Teffs) or no cells. The resident F4/80+ macrophages of the recipient mice injected with the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs displayed significantly increased phagocytosis of chicken red blood cells (cRBCs) and arginase activity together with increased IL-10 production, whereas these macrophages also showed decreased immunogenicity and nitric oxide (NO) production. Blocking arginase partially but significantly reversed the effects of CD4+CD25+ Tregs with regard to the induction of the M2 macrophages in vivo. Therefore, the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs can induce the M2 macrophages in recipient mice at least in part via an arginase pathway. We have provided in vivo evidence to support the unknown pathways by which allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs regulate innate immunity in recipient mice by promoting the differentiation of M2 macrophages.

Keywords: alternatively activated macrophages, arginase, classically activated macrophages, immune tolerance, mouse, transplantation

Introduction

Mononuclear phagocytes are an important part of innate immunity and are closely involved in pathogen and tissue debris clearance and in shaping the adaptive immune responses.1,2 In addition to acting as a first line of resistance against pathogens and activating adaptive responses, mononuclear phagocytes also undergo reprogramming of their functional properties in response to signals derived from microbes, damaged tissues and resting or activated lymphocytes in either physiological or pathological states.3,4 Mirroring T helper type 1 (Th1)–Th2 polarization, two distinct states of polarized activation for macrophages have been recognized: the classically activated (M1) and the alternatively activated (M2) macrophages.5,6 Th1 cells can drive classical M1 polarization of macrophages via interferon (IFN)-γ. These M1 cells are characterized by their ability to release large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, IL-23 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates, increased expression of MHC II and costimulatory molecules, efficient antigen presentation and microbicidal or tumoricidal activity.7,8 Through the expression of cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-12, CXCL9 and CXCL10, M1 macrophages drive the polarization and recruitment of Th1 cells, thereby amplifying a type 1 response.9 The Th2 cell-derived cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13, direct M2 polarization of macrophages during helminth infection and allergy. Indeed, some prototypical mouse M2 markers, such as YM1, FIZZ1 and MGL, were identified during parasite infection and allergic inflammation. IL-4- or IL-10-treated macrophages displayed low expression of IL-12 and high expression of IL-10, IL-1 decoy receptor and IL-1RA and shared the features of M2 macrophages.10,11

M2 macrophages have been implicated in the control of CD4+ T cell hyporesponsiveness via the induction of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) or the inhibition of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells.6,12 Accordingly, different macrophage subsets may play distinct roles in modulating either the immune response or tolerance. It is now known that human CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs can induce the alternative activation of human macrophages/monocytes in vitro.13,14 Our previous in vivo results showed that in severe combined immunodeficiency mice, the adoptive transfer of syngeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs into the peritoneal cavity polarizes F4/80+ macrophages into an M2 phenotype.15

Bone marrow transplantation is used in clinics to treat patients with leukemia or other relevant diseases.16,17 However, graft-versus-host disease remains a major barrier for the clinical application of HLA-mismatched bone marrow transplantation.18,19,20 The protective effect of donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs in graft-versus-host disease has been previously demonstrated.21,22 In addition to the inhibition of T effector cells (Teffs) by CD4+CD25+ Tregs, whether allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs has regulatory effects on recipient macrophages or other antigen-presenting cells in vivo has not yet been determined. In this study, we investigated the effects of allogeneic donor mouse CD4+CD25+ Tregs on recipient mouse F4/80+ macrophages in vivo by the adoptive transfer of allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs directly into the peritoneal cavity of immunodeficient NOD-scid mice. Notably, the results indicated that in contrast to the CD4+CD25− Teffs, the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs could efficiently induce M2 macrophages via an arginase pathway. Furthermore, the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs and CD4+CD25− Teffs displayed strong antagonistic effects with regard to the regulation of macrophage polarization.

Materials and methods

Animals

Six- to seven-week-old C57BL/6 (B6; H-2b), BALB/c (H-2d) and NOD-scid (NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid) mice (H-2g7) were purchased from the Beijing University Experimental Animal Center (Beijing, China) and the National Rodent Laboratory Animal Resources, Shanghai Branch (Shanghai, China). All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility and were housed in microisolator cages containing sterilized feed, autoclaved bedding and water. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Isolation and adoptive transfer of CD4+ T-cell subsets

Enriched CD4+CD25+ T-cell and CD4+CD25− T-cell populations were isolated from mouse splenocytes using either a CD4+CD25+ Tregs isolation kit with the MidiMACS Separator according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) or a FACSAria flow cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA, USA) to sort these cell populations as described previously.23 The sorted CD4+CD25+ T-cell and CD4+CD25− T-cell populations had purities greater than 90% and 95%, respectively. The cell viability was typically greater than 95% as determined by trypan blue exclusion.24 Freshly isolated 1×106 BALB/c CD4+CD25+T cells, CD4+CD25−T cells or both cells at a ratio of 1∶1 were directly transferred into the allogeneic NOD-scid mouse peritoneal cavity.

Preparation of peritoneal macrophages

Mouse peritoneal exudate cells were obtained from the peritoneal exudates of mice as previously described.17,25,26 Briefly, the peritoneal exudate cells were washed twice with cold Hanks' solution and adjusted to 5×106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA). The cells were cultured in 2% gelatin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA)-pretreated six-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) for 3–4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The non-adherent cells were removed by washing with warm RPMI 1640 medium. The adherent cells were harvested with 5 mM EDTA (Sigma) in ice-cold phosphate-buffered solution (PBS, pH 7.2), and the cell density was adjusted to 1×106 cells/ml. The purity of the isolated macrophages was typically >90% as determined by F4/80+ cells, and the cell viability was typically greater than 95% as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry (FCM)

The macrophages (5×105) were washed once with FACS buffer (PBS, 0.1% NaN3 and 0.5% bovine serum albumin, BSA). For three-color staining, the cells were stained with PE-labeled anti-F4/80 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and antigen-presenting cell-anti-CD11c monoclonal antibody (mAb) and either FITC-labeled anti-MHC II (M5), CD80 (16-10A1), CD86 (GL1), CD40 (3/23), CD54 (3E2), CD23 (B3B4), programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1; 1-111A), TLR2 (mT2.7) mAb, or the non-specific staining control mAb. Anti-mouse FcR mAb (2.4G2) was used prior to staining to block any non-specific FcR binding. At least 10 000 cells were assayed using a FASCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed with CellQuest software (San Jose, CA, USA). Non-viable cells were excluded using the vital nucleic acid stain, propidium iodide). Certain molecular expression levels were determined as the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cells that were positively stained with the specific mAb.24,27

IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-12 expression in the macrophages was detected using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus with GolgiPlug intracellular staining kits (BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA). The macrophages were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) in six-well plates for approximately 18 h. During the last 4–6 h of culture, 1 ml aliquots of cells were pulsed with 1 µL BD GolgiPlug containing brefeldin A (BD Biosciences PharMingen). The macrophages were collected and washed once with FACS buffer. After incubation with the anti-FcR mAb (2.4G2) and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse F4/80 mAb in the dark at room temperature for 15 min, the cells were washed once with staining buffer and then fixed and permeabilized with 500 µl BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution at room temperature in the dark for 20 min according to the manufacturer's instructions. Next, the cells were stained with either 0.25 µg PE-labeled anti-IFN-γ (GIR-208), IL-4 (11B11), IL-10 (JES5-16E3), IL-12 (C17.8), TNF-α (MP6-XT22) or IL-17A (eBio17B7) mAb for 30 min at room temperature in the dark and washed three times, and 10 000 F4/80+ cells were then analyzed by FCM.26,28,29

Arginase assay

The arginase activity assay was performed as previously described.30,31 Briefly, the cells were lysed in 0.1% Triton X-100. Tris-HCl was then added to the cell lysates at a final concentration of 12.5 mM, and MnCl2 was added to obtain a 1 mM final concentration. The arginase was activated by heating for 10 min at 56 °C, and the L-arginine substrate was added at a final concentration of 250 mM. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and halted by the addition of H2SO4/H3PO4. After the addition of α-isonitrosopropiophenone and heating for 30 min at 95 °C, the urea production was measured as the absorbance at 540 nm, and the data were normalized to the total protein content.

Nitric oxide (NO) production

NO production by the macrophages was determined by measurement of the nitrite concentration with the Griess assay.32,33 The supernatants (100 µl) were added to 100 µl of a 1∶1 mixture of 1% sulfanilamide dihydrochloride (Sigma) and 0.1% naphthyl ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma) in 2.5% H3PO4. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, and the absorbance at 550 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The nitrite concentration was calculated with a sodium nitrite standard curve as reported previously.28

Detection of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10

The levels of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 in the mouse sera were determined by specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (R&D) 3 days after the adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25+ Tregs or CD4+CD25− T cells into the NOD-scid mice.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)

CD4+ T cells were purified by the negative selection of BALB/c mouse splenocytes using a mouse CD4+ T lymphocyte enrichment set (BD Biosciences PharMingen). CD4+ T responders (2×105) and macrophage stimulators (1×105), which were pre-treated with 50 µg/mL mitomycin C, were incubated in triplicate in 0.2 mL medium in U-bottomed 96-well microplates (Costar) at 37 °C in 5% CO2.18,28,34,35 The plates were pulsed with 1 µCi of 3H-labeled thymidine (radioactivity, 185 GBq/mM; Atomic Energy Research Establishment, Beijing, China) per well on day 3, and after 18 h of further incubation, the cells were harvested onto glass fiber filters with an automatic cell harvester (Tomtec, Toku, Finland). The samples were assayed in a liquid scintillation analyzer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA). The values were expressed as the counts per minute from the triplicate wells and are the results after subtracting the counts per minute from wells without stimulants.36

Phagocytosis of chicken red blood cells (cRBCs) in vivo

A single-cell suspension of cRBCs was freshly obtained. After two washes with PBS, 1×107 cells/mL cRBCs were labeled with 5 µM 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 15 min at 37 °C. These cells were then washed thoroughly and re-suspended at a concentration of 1×107cells/ml. Cell viability was typically greater than 95%. A suspension of CFSE-labeled cRBCs (1 ml) was injected into the peritoneal cavity of the NOD-scid mice 3 days after the adoptive transfer of no cells, CD4+CD25+ T cells or CD4+CD25− T cells. At 6–10 h after the injection of the cRBCs, the F4/80+macrophages were collected as described above. The cells were first stained with anti-mouse FcγR mAb (2.4G2) to block any nonspecific staining and then stained with PE-conjugated anti-F4/80 mAb. After three washes with FACS buffer, the phagocytosis percentage of the F4/80+ cells was determined by FCM. In parallel, a portion of the peritoneal macrophages was spotted onto coverslips. As reported previously,34,37 the adherent cells were stained with Giemsa stain and Wright staining solution (Sigma) after fixation in methanol.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and the cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). An ABI 7900 Real-Time PCR system was used for the quantitative PCR with primer and probe sets from Applied Biosystems. The probe sets were as follows: IL-23, PD-L2, ICOSL, CXCL9, CXCL10, CCL22, inducible NO synthase (iNOS) and Arginase I. The results were analyzed with SDS 2.1 software. The cycling threshold value of the endogenous control gene, Hprt1, which encodes for hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase, was subtracted from the cycling threshold value of each target gene to generate the change in cycling threshold. The expression of each target gene is presented as the fold change relative to the control samples. The sequences of the primers used for the real-time PCR assays are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. The sequences of the primers used for real-time PCR assays.

| Genes | Primers |

|---|---|

| Arginase1-S | CCAGAAGAATGGAAGAGTCAGTGT |

| Arginase1-R | GCAGATATGCAGGGAGTCACC |

| iCOSL-S | CTTGGAAGAGGTGGTCAGGCT |

| iCOSL-R | GCCGTGTCTATTAGGCTATTGTCC |

| iNOS-S | CACCAAGCTGAACTTGAGCG |

| iNOS-R | CGTGGCTTTGGGCTCCTC |

| IL-23-S | CTGAGAAGCAGGGAACAAGATG |

| IL-23-R | GAAGATGTCAGAGTCAAGCAGGTG |

| PD-L2-S | GCAGTACCGTTGCCTGGTCATCT |

| PD-L2-R | GGTCCTGATGTGGCTGGTGTTGG |

| CXCL9-S | CCACTACAAATCCCTCAAAGAC |

| CXCL9-R | TCTAGGCAGGTTTGATCTCC |

| CXCL10-S | CGTCATTTTCTGCCTCATCC |

| CXCL10-R | GCAATGATCTCAACACGTGG |

| CCL22-S | TCAAAATCCTGCCGCAAG |

| CCL22-R | CTCGGTTCTTGACGGTTATC |

| HPRT-S | AGTACAGCCCCAAAATGGTTAAG |

| HPRT-R | CTTAGGCTTTGTATTTGGCTTTTC |

Abbreviations: iNOS, inducible NO synthase; PD-L2, programmed cell death-ligand 2.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean±s.d. The Student's unpaired t-test for the comparison of means was used to compare the groups. A P value less than 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs promoted the phenotypic alteration of recipient F4/80+ macrophages

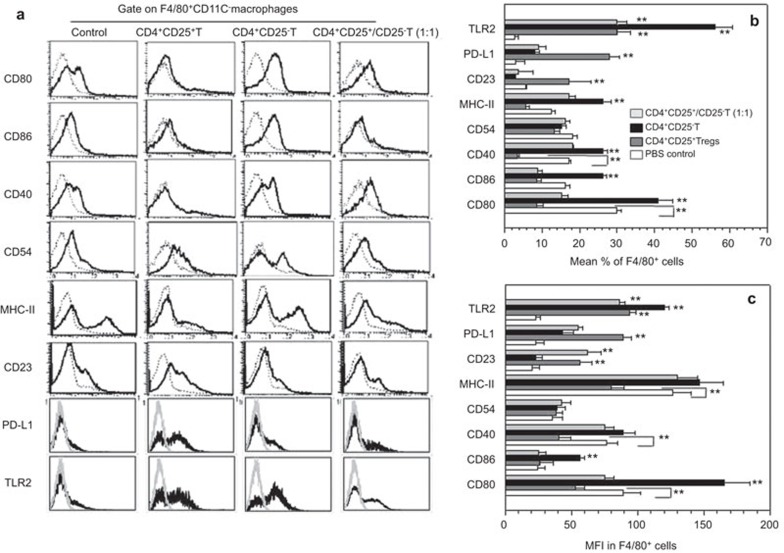

To determine whether CD4+CD25+ Tregs can regulate allogeneic macrophages, we first studied the phenotypic alteration of F4/80+ macrophages caused by allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs using a mouse model in which allogeneic BALB/c (H-2d) CD4+CD25+ Tregs, CD4+CD25− Teffs or both cells (1∶1) were adoptively transferred into the peritoneal cavity of NOD-scid recipient mice (H-2g7). Three days after the adoptive transfer of these cells, the percentages of F4/80+ macrophages expressing CD80, CD86, CD40 or MHC II were significantly increased in the mice that received the allogeneic CD4+CD25− Teffs compared to the control mice that did not receive any cells. However, the percentages of peritoneal resident F4/80+ macrophages in the recipient mice expressing CD80, CD86, CD40 or MHC II molecules were significantly decreased in the NOD-scid mice that received the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs compared to the mice that received either no cells or the CD4+CD25− Teffs (P<0.01, Figure 1). The MFIs of CD80, CD40 and MHC II but not CD86 were significantly decreased in the NOD-scid mice that received the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs compared to the mice that received either no cells or the CD4+CD25− Teffs (Figure 1). The percentages of macrophages expressing CD54 and the MFI of CD54 expression on the macrophages were comparable for all the treated groups. Notably, the percentages of CD23+ cells, which are regarded as markers of M2 macrophages,3,26 in the F4/80+ macrophage populations, were enhanced in the mice that received the CD4+CD25+ Tregs compared to the control mice that received no cells and the mice that received the CD4+CD25− Teffs. PD-L1 and PD-L2 are ligands for PD-1, which is a costimulatory molecule that plays an inhibitory role in regulating T-cell activation in the periphery. Notably, the percentage of PD-L1+ cells in the F4/80+ macrophage population, and the MFI of PD-L1 expression were significantly increased in the mice that received the CD4+CD25+ Tregs compared to the control mice that did not receive any cells. PD-L2 expression in the macrophages was significantly increased in the mice that received either the CD4+CD25+ Tregs or the CD4+CD25− Teffs compared to the control mice that did not receive any cells. This expression was determined by real-time PCR (Supplementary Figure 1). However, there was no difference in PD-L2 expression in the macrophages isolated from the mice that received either the CD4+CD25+ Tregs or the CD4+CD25− Teffs (P>0.05, Supplementary Figure 1). The inducible costimulator, ICOS, and its ligand, ICOS-L, have been shown to play diverse roles in immunity and autoimmunity. The mRNA expression level of ICOS-L in the macrophages was comparable among the mice that received no cells, CD4+CD25+ Tregs, CD4+CD25− Teffs or both cells (Supplementary Figure 1). Furthermore, TLR2 expression was also significantly increased in the mice that received the CD4+CD25+ Tregs and the CD4+CD25− Teffs compared to the control mice that did not receive cells. TLR4 expression on the macrophages was identical among these groups (data not shown). Importantly, the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs efficiently reversed the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25− Teffs-induced upregulation of CD80, CD86, CD40 and MHC II expression (Figure 1b and c). Additionally, an identical observation was obtained with respect to the MFI value of the costimulatory molecule expression levels. These data indicate that the distinct phenotypes of the recipient mouse macrophages were induced by the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs and CD4+CD25− Teffs.

Figure 1.

Recipient macrophage phenotypic alterations induced by allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs and CD4+CD25− T cells in NOD-scid mice. (a) A representative flow cytometry result of F4/80+CD11c− macrophages stained with anti-CD80, CD86, CD40, CD54, MHC II, CD23, PD-L1 and TLR2 mAb. Phenotype characteristics of the NOD-scid mouse recipient macrophages that received none of the cells, donor allogeneic CD4+CD25+ T cells, or CD4+CD25− T cells. The macrophages were stained with PE-labeled anti-F4/80 and APC-labeled anti-CD11c mAbs and either FITC-labeled anti-CD80, CD86, MHC II, CD40, CD54, CD23, PD-L1 or TLR2 mAb. The assays were performed 3 days after the adoptive transfer. Ten thousand F4/80+ cells were analyzed by FCM. The gray lines represent the non-specific mAb staining and the black lines indicate the mAb staining. (b) The percentages of MHC II-, CD80-, CD86-, CD40-, CD54-, CD23-, PD-L1- and TLR2+ cells in the F4/80+ macrophages of the NOD-scid mice that received no cells, allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ T cells or CD4+ CD25− T cells. (c) The MFI of MHC II, CD80, CD86, CD40, CD54, CD23, PD-L1 and TLR2 in the F4/80+ macrophages as determined by FCM. **P<0.01 compared to the indicated groups. The data are the mean±s.d. (N=6). APC, antigen-presenting cell; FCM, flow cytometry; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs enhanced the phagocytic ability of recipient macrophages

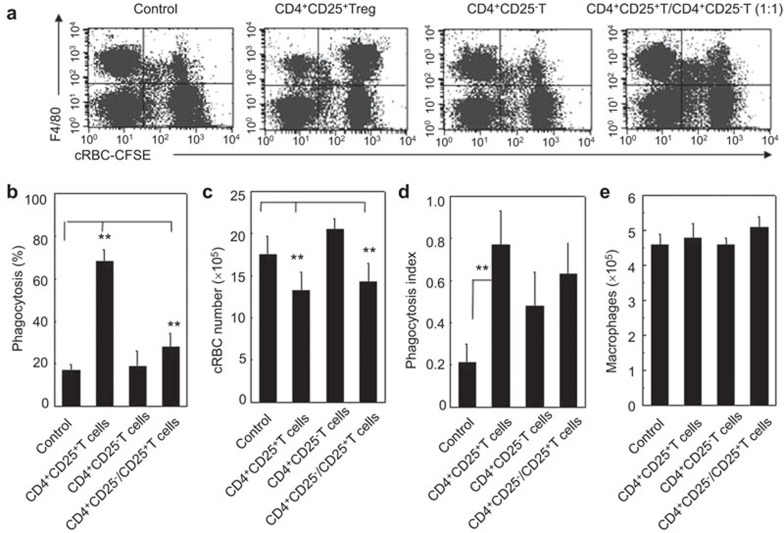

Phagocytosis represents an early and critical event in triggering the host defense macrophages against invading pathogens. The phagocytosis of unopsonized cRBCs by peritoneal F4/80+ macrophages in NOD-scid mice that received the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs, CD4+CD25− Teffs or both cells (1∶1) was detected by FCM or microscopy as described in the section on ‘Materials and methods'. As shown in Figure 2, the F4/80+ macrophages in the mice that received the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs exhibited significantly higher rates of phagocytosis of the cRBCs than the mice that received either the CD4+CD25− Teffs or no cells. This result was demonstrated by the phagocytosis percentage, the number of non-phagocytosed/cleared cRBCs (Figure 2a–c) and the phagocytosis index (Figure 2d). By contrast, the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25− Teffs did not significantly alter the phagocytic ability of the F4/80+ macrophages. The antagonism between the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs and the CD4+CD25− Teffs was also observed with respect to the regulation of macrophage phagocytosis. Notably, the absolute numbers of macrophages in the peritoneal cavity were identical in all the mice (P>0.05, Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

The increased phagocytosis of recipient macrophages by allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs in NOD-scid mice. (a) A representation of the FCM displaying the recipient resident macrophage phagocytosis of CFSE-cRBCs is shown. The phagocytosis ability of the resident macrophages against cRBCs in the NOD-scid mice that received no cells, allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ T cells, CD4+CD25− T cells or both CD4+CD25+ T cells and CD4+CD25− T cells was determined by FCM 3 days after the adoptive transfer. (b) The percentage of phagocytosing macrophages in NOD-scid mice that received no cells, CD4+CD25+ T cells, CD4+CD25− T cells or both CD4+CD25+ T cells and CD4+CD25− T cells were summarized. (c) The number of non-phagocytized/cleared cRBCs by recipient macrophages was summarized. (d) The phagocytosis of cRBCs by macrophages as detected by Giemsa–Wright staining. The phagocytosis index against cRBCs by macrophages was summarized. (e) The total cell numbers of macrophages isolated from mouse peritoneal exudates was summarized. The cells were harvested 3 days after the adoptive transfer of the sorted T cell subsets. Six mice in each group were assayed. The data are the mean±s.d. (N=5). **P<0.01 between the indicated groups. One representative of three independent experiments with similar results is shown. CFSE, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester; cRBC, chicken red blood cell; FCM, flow cytometry; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs inhibited the immunogenicity of the recipient mouse macrophages

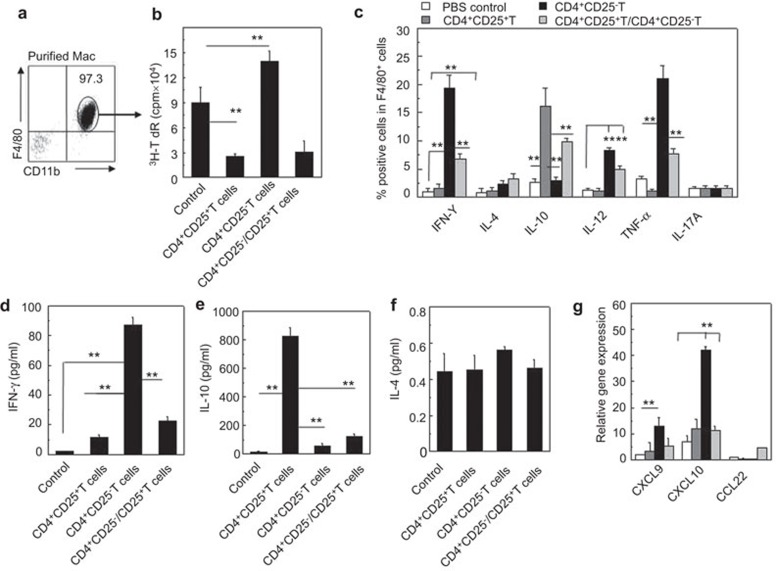

Macrophages play a critical role in the initiation of the adaptive immune response. Macrophages are isolated from the peritoneal cavity and the purity is confirmed by FCM as shown in Figure 3a. The immunogenicity of the F4/80+ macrophages that were separated from the NOD-scid mice that received the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs or CD4+CD25− Teffs or both cells (1∶1) was investigated in vitro. As shown in Figure 3a, there was significantly decreased immunogenicity of the F4/80+ macrophages that were separated from the NOD-scid mice that received the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs to the allogeneic T cells compared to the macrophages from the mice that received either the CD4+CD25− Teffs or no cells. This result was determined by MLR assays (P<0.01, Figure 3a). However, the allogeneic CD4+CD25− Teffs somewhat increased the immunogenicity of the macrophages to the allogeneic T cells compared to the mice that did not receive cells (P<0.01, Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Altered immunogenicity and cytokine and chemokine secretion of recipient macrophages induced by allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs in NOD-scid mice. (a) The recipient resident macrophages were isolated and the purity was confirmed with CD11b and F4/80 double staining by FCM. (b) The immunogenicity of the recipient resident macrophages was assessed with MLR. The proliferation of BALB/c CD4+ T cells induced by the allogeneic macrophages isolated from NOD-scid mice that received no cells, CD4+CD25+ T cells, CD4+CD25− T cells or both CD4+CD25+ T cells and CD4+CD25− T cells was determined by 3H-TdR incorporation in vitro. (c) Cytokine production by recipient F4/80+ macrophages was determined by two-color intracellular staining FCM. The percentages of IFN-γ+, IL-4+, IL-10+, IL-12+, TNF-α+ and IL-17A+ cells in F4/80+ macrophages were determined after the cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml). (d–f) The cytokine levels in the peripheral blood of recipient NOD-scid mice were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assayA 3 days after the adoptive transfer of the indicated cells. (g) The relative mRNA expression of the chemokines, CXCL9, CXCL10 and CCL22, in the peritoneal macrophages of the recipient NOD-scid mice, was analyzed by real-time PCR. More than five mice in each group were assayed. The data are the mean±s.d. **P<0.01 among the indicated groups. FCM, flow cytometry; IFN, interferon; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MLR, mixed lymphocyte reaction, TNF, tumor-necrosis factor; Treg, regulatory T cell.

In addition, the cytokine expression of the macrophages was analyzed. As shown in Figure 3b, the peritoneal F4/80+ macrophages in the recipient mice that received the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs exhibited significantly higher IL-10 expression levels than the mice that received either the CD4+CD25− T cells or no cells (P<0.01). The F4/80+ macrophages in the recipient mice that received the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25− Teffs showed higher levels of IFN-γ, IL-12 and TNF-α but not IL-17A; however, the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs did not significantly alter the secretion of these cytokines (P<0.01, Figure 3b). IL-4 production by the F4/80+ macrophages was similar among these groups (Figure 3b and f). The IFN-γ, IL-12 and TNF-α but not IL-17A production by the F4/80+ macrophages induced by the allogeneic CD4+CD25− Teffs was inhibited by the cotransfer of allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs (P<0.01, Figure 3b). The mRNA expression level of IL-23 in the macrophages isolated from the mice that received either the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs or CD4+CD25− Teffs was higher than in the mice that did not receive T cells. The allogeneic CD4+CD25− Teffs induced more IL-23 production than the CD4+CD25+ Tregs (P<0.01, Supplementary Figure 2). The recipient mouse serum cytokine levels were also investigated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays 3 days after the adoptive transfer of the T cells. Consistently, the recipient mice that received the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs showed lower IFN-γ and higher IL-10 levels compared to the mice that received either the CD4+CD25− T cells or no cells (P<0.01, Figure 3d and e). The IL-4 levels in the sera of the recipient mice were identical regardless of whether the mice received T cells or not. The M1-associated chemokine genes, CXCL10 and CXCL9, are significantly increased in the macrophages isolated from the mice that received the CD4+CD25− Teffs compared to the control mice or the mice that received the CD4+CD25+ Tregs (P<0.01, Figure 3g). The M2-associated chemokine gene, CCL22, was not significantly different among these mice.

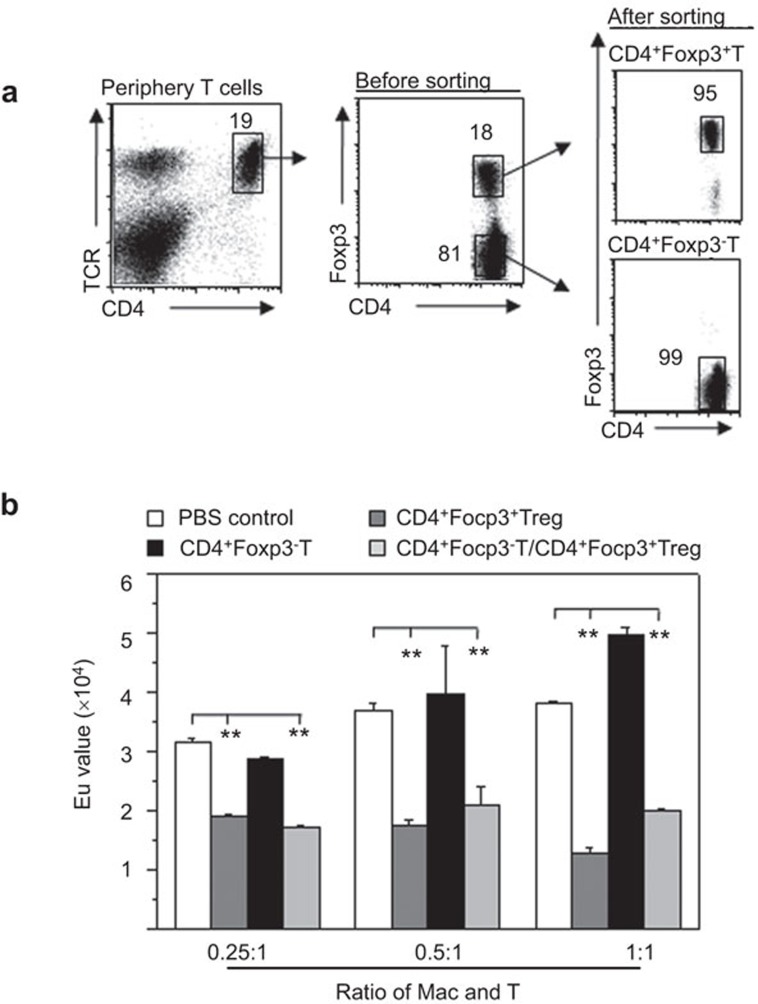

Allogeneic donor CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs induced functional stable macrophages in recipient mice

To investigate the functional stability of the changes in the recipient mouse macrophages that were induced by the allogeneic CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs, we used a Foxp3-GFP knock-in mice. The CD4+Foxp3+ Treg and CD4+Foxp3− T cells in the periphery were sorted from these mice and the purity was determined by FCM (Figure 4a). Seven to eight days after the cells were transferred into the recipient mice, the immunogenicity of the recipient mouse peritoneal macrophages was investigated. The results showed that there was significantly decreased immunogenicity to the allogeneic T cells of the F4/80+ macrophages isolated from the NOD-scid mice that received the CD4+CD25+ Tregs compared to the mice that received either the CD4+CD25− Teffs or no cells (Figure 4b). This finding suggests that the recipient macrophages that were induced by the CD4+CD25+ Tregs displayed stable functional characteristics in vivo for at least 1 week.

Figure 4.

Functional stability of recipient macrophages induced by allogeneic donor CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs in NOD-scid mice. (a) Allogeneic donor CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs and CD4+Foxp3− T cells were sorted from Foxp3-GFP knock-in mice and confirmed by FCM. (b) After the adoptive transfer of isolated T-cell subsets for 7–8 days, the immunogenicity of the recipient resident macrophages was assessed by MLR. The proliferation of B6 CD4+ T cells that were induced by the allogeneic macrophages isolated from the NOD-scid mice that received no cells, CD4+Foxp3+ T cells, CD4+Foxp3− T cells or both CD4+Foxp3+ T cells and CD4+Foxp3− T cells was determined by a BrdU proliferation analysis in vitro. The data are presented as the mean±s.d. (N=4–5). **P<0.01 compared to the indicated groups. FCM, flow cytometry; MLR, mixed lymphocyte reaction; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs induced M2-like macrophages in recipient mice

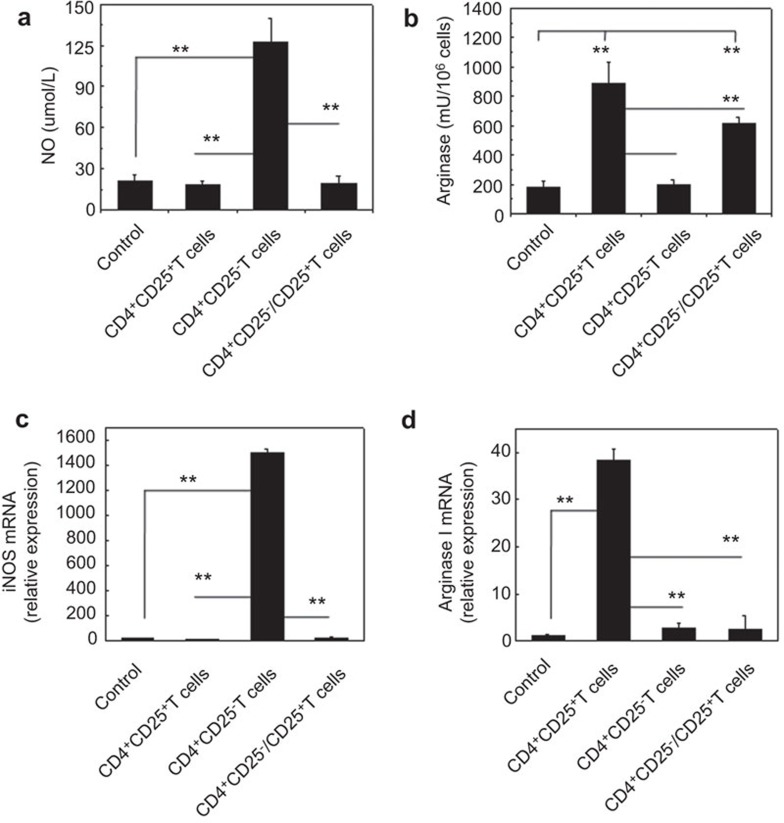

Depending on the activating stimuli, macrophages can either develop into M1 or M2 macrophage subsets. L-arginine metabolism is an important branch point in this differential activation that leads to the development of either M2 or M1 macrophages. Therefore, the production of NO and arginase by the macrophages in this models was investigated. As shown in Figure 5, F4/80+ macrophages of the recipient mice that received the CD4+CD25+ T cells showed significantly higher arginase activity and lower NO production than the mice that received either the allogeneic CD4+CD25− T cell or no cells (P<0.01, Figure 5a and b). Consistently, the mRNA analysis showed higher arginase I and lower iNOS mRNA expression levels in the recipient F4/80+ macrophages of the mice that received the CD4+CD25+ Tregs, but not the CD4+CD25−Teffs or no cells (P<0.01, Figure 5c and d). These data suggest that allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs, similar to syngeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs,15 could induce M2-like macrophages in the recipient mice in vivo, whereas allogeneic CD4+CD25− Teffs promote recipient M1-like macrophage differentiation.

Figure 5.

Increased arginase expression in recipient macrophages isolated from mice with allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs. The NO secretion (a) and arginase activity (b) of macrophages isolated from recipient NOD-scid mice adoptively transferred with no cells, CD4+CD25+ T cells, CD4+CD25− T cells or both CD4+CD25+ T cells and CD4+CD25− T cells for 3 days. The mRNA levels of iNOS (c) and arginase I (d) of the recipient macrophages from NOD-scid mice were also determined by real-time PCR. The recipient NOD-scid mice were adoptively transferred no cells, CD4+CD25+ T cells, CD4+CD25− T cells or both CD4+CD25+ T cells and CD4+CD25− T cells for 3 days prior to macrophage harvesting. The data are presented as the mean±s.d. (N=6). **P<0.01 compared to the indicated groups. iNOS, inducible NO synthase; NO, nitric oxide; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Induction of recipient M2-like macrophages by allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs is dependent on an arginase pathway

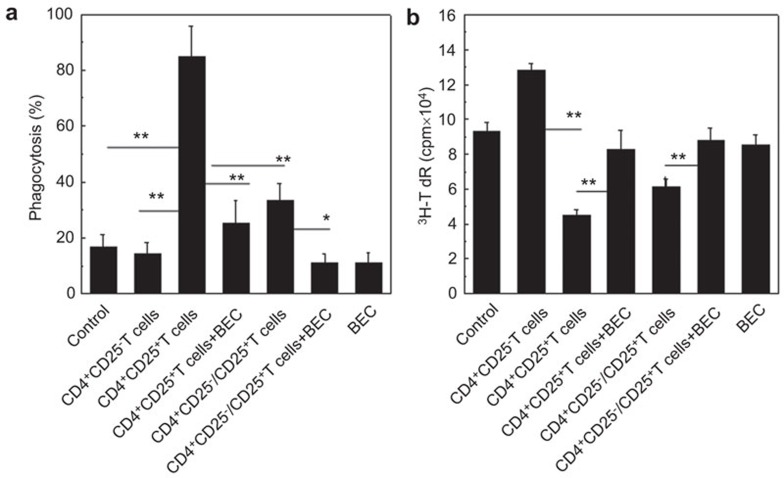

The development of M2 macrophages is dependent on the arginase pathway. To investigate the role of the arginase pathway in the induction of recipient M2-like macrophages by allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs, we treated NOD-scid mice daily with 0.2% S-(2-boronoethyl)-l-cysteine (BEC), an arginase inhibitor. The BEC was administered in the drinking water starting at day −1 of the adoptive transfer of the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs until the end of the experiment (day 3). The results indicated that BEC treatment could significantly reverse the enhanced phagocytosis of cRBCs by F4/80+ macrophages and the decreased immunogenicity of recipient F4/80+ macrophages that was induced by the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs in the NOD-scid mice (Figure 6). These data demonstrate that the development of recipient M2-like macrophages that is induced by the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs is dependent on the arginase pathway.

Figure 6.

Recipient M2-like macrophages induced by allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs are dependent on arginase signaling pathways. (a) Phagocytosis of cRBCs by recipient macrophages of NOD-scid mice that received either the donor allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs or the CD4+CD25+ Tregs and the arginase inhibitor, BEC, as detected by FCM. (b) The immunogenicity of the recipient macrophages was assessed by MLR. The proliferation of BALB/c CD4+ T cells induced by the allogeneic donor macrophages that were isolated from the NOD-scid mice that received no cells, CD4+CD25− T cells, or CD4+CD25+ T cells either alone or in combination with BEC or BEC alone was determined by 3H-TdR incorporation in vitro. The data are the mean±s.d. (N=5). One representative of two independent experiments with similar results was shown. **P<0.01 compared among the indicated groups. BEC, S-(2-boronoethyl)-l-cysteine; cRBC, chicken red blood cell; FCM, flow cytometry; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Discussion

The functional polarization of macrophages into M1 or M2 cells is a simplified conceptual framework that describes the plasticity of mononuclear phagocytes.35,38,39 As demonstrated by our studies and those of others, syngeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs have been shown to be critical for the induction of the macrophage phenotype switch both in vivo and in vitro.14,15 In this study, the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs caused significant phenotypic and functional alterations of the resident macrophages in the recipient NOD-scid mice to an M2-like phenotype. This study collectively showed that the allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs and CD4+CD25− Teffs could induce host M2 and M1 macrophages, respectively. Therefore, the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs could regulate the recipient immune response by promoting the differentiation of M2-like macrophages.

It has been reported that M2 macrophages may be induced by IL-10, TGF-β, IL-4 or/and IL-13.30,40,41,42 M2 macrophages produce high levels of arginase I, which efficiently converts L-arginine into urea and ornithine.3,4 In this model, the recipient resident macrophages expressed high levels of IL-10 and low levels of IFN-γ, IL-12 and TNF-α when the mice received the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs cells, whereas injection of allogeneic donor CD4+CD25− Teffs caused the recipient macrophages to produce more IFN-γ, IL-12 and TNF-α in the NOD-scid mice. Furthermore, the enhanced phagocytosis and decreased antigen-presenting ability of the host resident macrophages that were induced by the allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs could be rescued by the arginase inhibitor, BEC, in vivo.7,8,9,11,30,43,44 These data provide metabolic enzyme evidence for the presence of polarized recipient M2-like macrophages and further suggest that the induction of M2-like macrophages by donor allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs is significantly dependent on arginase signaling pathways.

In summary, allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs could directly induce a phenotypic and functional switch of the recipient resident macrophages in vivo, which is distinct from the allogeneic donor CD4+ Teffs. In this study, our data offer direct evidence to support the fact that allogeneic donor CD4+CD25+ Tregs induce host M2-like macrophage polarity, whereas allogeneic CD4+ Teffs promote host M1-like macrophages in vivo, which is dependent on the arginase signaling pathway. Therefore, this evidence indicates that either allogeneic donor or recipient CD4+ T cell subsets may mediate the reciprocal induction pathways for recipient or graft M1 and M2 macrophages. The antagonistic effects of donor allogeneic CD4+CD25+ Tregs and CD4+ Teffs on recipient macrophages may contribute to the maintenance or induction of immune tolerance during transplantation.

Author contributions

Xuelian Hu participated in the research design, performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Guangwei Liu participated in the research design, performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Yuzhu Hou participated in the performance of the experiments. Jianfeng Shi participated in the performance of the experiments. Linnan Zhu participated in the performance of the experiments. Di Jin participated in the performance of the experiments involving the mouse models. Jianxia peng participated in the performance of the research and reagent preparation. Yong Zhao participated in the research design, data analysis and the writing of the manuscript. Xuelian Hu and Guangwei Liu contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs Shuping Zhou and Zeqing Niu for their kind review of the manuscript, Ms Jing Wang, Mr Yabing Liu and Ms Xiaoqiu Liu for their expert technical assistance, Ms Qinghuan Li and Jianxia Peng for their excellent laboratory management and Mr Baisheng Ren for his outstanding animal husbandry. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (C81072396, U0832003, YZ; C31171407 and 81273201, GL), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2010CB945301, YZ) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences for Distinguished Young Scientists (KSCX2-EW-Q-7, GL)..

The authors have declared that no conflict of interests exists.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cellar & Molecular Immunology's website (http://www.nature.com/cmi)

Supplementary Information

References

- Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafei M, Hsieh J, Zehntner S, Li M, Forner K, Birman E, et al. A granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-15 fusokine induces a regulatory B cell population with immune suppressive properties. Nat Med. 2009;15:1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/nm.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G, Pan PY, Eisenstein S, Divino CM, Lowell CA, Takai T, et al. Paired immunoglobin-like receptor-B regulates the suppressive function and fate of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunity. 2011;34:385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda E, Ho V, Ruschmann J, Antignano F, Hamilton M, Rauh MJ, et al. SHIP represses the generation of IL-3-induced M2 macrophages by inhibiting IL-4 production from basophils. J Immunol. 2009;183:3652–3660. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varin A, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: immune function and cellular biology. Immunobiology. 2009;214:630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber T, Ehlers S, Heitmann L, Rausch A, Mages J, Murray PJ, et al. Autocrine IL-10 induces hallmarks of alternative activation in macrophages and suppresses antituberculosis effector mechanisms without compromising T cell immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183:1301–1312. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Hirota K, Yoshitomi H, Maeda S, Teradaira S, Akizuki S, et al. Complement drives Th17 cell differentiation and triggers autoimmune arthritis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1135–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegaard JI, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Goforth MH, Morel CR, Subramanian V, Mukundan L, et al. Macrophage-specific PPARgamma controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature. 2007;447:1116–1120. doi: 10.1038/nature05894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser DM. The many faces of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:209–212. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taams LS, van Amelsfort JM, Tiemessen MM, Jacobs KM, de Jong EC, Akbar AN, et al. Modulation of monocyte/macrophage function by human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemessen MM, Jagger AL, Evans HG, van Herwijnen MJ, John S, Taams LS. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of human monocytes/macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19446–19451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706832104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Ma H, Qiu L, Li L, Cao Y, Ma J, et al. Phenotypic and functional switch of macrophages induced by regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in mice. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89:130–142. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johrens K, Franke A, Dietel M, Anagnostopoulos I. Non-neoplastic TdT-positive cells in bone marrow trephines with acute myeloid leukaemia before and after treatment express myeloid molecules. Pathobiology. 2011;78:35–40. doi: 10.1159/000322974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Adrian FJ, Jahnke W, Cowan-Jacob SW, Li AG, Iacob RE, et al. Targeting Bcr-Abl by combining allosteric with ATP-binding-site inhibitors. Nature. 2010;463:501–506. doi: 10.1038/nature08675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawara I, Shlomchik WD, Jones A, Zou W, Nieves E, Liu C, et al. A crucial role for host APCs in the induction of donor CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell-mediated suppression of experimental graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2010;185:3866–3872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peggs KS, Mackinnon S. Exploiting graft-versus-tumour responses using donor leukocyte infusions. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2001;14:723–739. doi: 10.1053/beha.2001.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korngold R. Pathophysiology of graft-versus-host disease directed to minor histocompatibility antigens. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;7 Suppl 1:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Terenzi A, Castellino F, Bonifacio E, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3921–3928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani AR, Storb RF. Separation of graft-vs.-tumor effects from graft-vs.-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Autoimmun. 2008;30:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Burns S, Huang G, Boyd K, Proia RL, Flavell RA, et al. The receptor S1P1 overrides regulatory T cell-mediated immune suppression through Akt-mTOR. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:769–777. doi: 10.1038/ni.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Zhao L, Wang H, Sun L, Yi H, Zhao Y. Presence of functional mouse regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in xenogeneic neonatal porcine thymus-grafted athymic mice. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2841–2850. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joerink M, Ribeiro CM, Stet RJ, Hermsen T, Savelkoul HF, Wiegertjes GF. Head kidney-derived macrophages of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) show plasticity and functional polarization upon differential stimulation. J Immunol. 2006;177:61–69. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Ma H, Jiang L, Peng J, Zhao Y. The immunity of splenic and peritoneal F4/80+ resident macrophages in mouse mixed allogeneic chimeras. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007;85:1125–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhao L, Sun Z, Sun L, Zhang B, Zhao Y. A potential side effect of cyclosporin A: inhibition of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in mice. Transplantation. 2006;82:1484–1492. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000246312.89689.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Xia XP, Gong SL, Zhao Y. The macrophage heterogeneity: difference between mouse peritoneal exudate and splenic F4/80+ macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:341–352. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha P, Clements VK, Bunt SK, Albelda SM, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Cross-talk between myeloid-derived suppressor cells and macrophages subverts tumor immunity toward a type 2 response. J Immunol. 2007;179:977–983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony RM, Urban JF, Jr, Alem F, Hamed HA, Rozo CT, Boucher JL, et al. Memory TH2 cells induce alternatively activated macrophages to mediate protection against nematode parasites. Nat Med. 2006;12:955–960. doi: 10.1038/nm1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng M, Huntley D, Huang IF, Foye-Jackson O, Wang L, Sarkissian A, et al. Alternatively activated macrophages in intestinal helminth infection: effects on concurrent bacterial colitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:4721–4731. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A, Ohnishi H, Okazawa H, Nakazawa S, Ikeda H, Motegi S, et al. Positive regulation of phagocytosis by SIRPbeta and its signaling mechanism in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29450–29460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh MJ, Ho V, Pereira C, Sham A, Sly LM, Lam V, et al. SHIP represses the generation of alternatively activated macrophages. Immunity. 2005;23:361–374. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GW, Ma HX, Wu Y, Zhao Y. The nonopsonic allogeneic cell phagocytosis of macrophages detected by flow cytometry and two photon fluorescence microscope. Transpl Immunol. 2006;16:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ginderachter JA, Meerschaut S, Liu Y, Brys L, de Groeve K, Hassanzadeh Ghassabeh G, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) ligands reverse CTL suppression by alternatively activated (M2) macrophages in cancer. Blood. 2006;108:525–535. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Yang K, Burns S, Shrestha S, Chi H. The S1P1–mTOR axis directs the reciprocal differentiation of TH1 and Treg cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1047–1056. doi: 10.1038/ni.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzachanis D, Berezovskaya A, Nadler LM, Boussiotis VA. Blockade of B7/CD28 in mixed lymphocyte reaction cultures results in the generation of alternatively activated macrophages, which suppress T-cell responses. Blood. 2002;99:1465–1473. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol. 2006;177:7303–7311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoves S, Krause SW, Schutz C, Halbritter D, Scholmerich J, Herfarth H, et al. Monocyte-derived human macrophages mediate anergy in allogeneic T cells and induce regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:2691–2698. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes G, Beschin A, Ghassabeh GH, de Baetselier P. Alternatively activated macrophages in protozoan infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke P, Gallagher I, Nair MG, Zang X, Brombacher F, Mohrs M, et al. Alternative activation is an innate response to injury that requires CD4+ T cells to be sustained during chronic infection. J Immunol. 2007;179:3926–3936. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Funaba M, Chen Y, Tsujimoto M. Activin A functions as a Th2 cytokine in the promotion of the alternative activation of macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;177:6787–6794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Locati M. Orchestration of macrophage polarization. Blood. 2009;114:3135–3136. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta C, Rimoldi M, Raes G, Brys L, Ghezzi P, Di Liberto D, et al. Tolerance and M2 (alternative) macrophage polarization are related processes orchestrated by p50 nuclear factor kappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14978–14983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809784106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.