Abstract

Aim:

To demonstrate the gene expression profiles mediated by hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx), we characterized the molecular features of pathogenesis associated with HBx in a human liver cell model.

Methods:

We examined gene expression profiles in L-O2-X cells, an engineered L-O2 cell line that constitutively expresses HBx, relative to L-O2 cells using an Agilent 22 K human 70-mer oligonucleotide microarray representing more than 21,329 unique, well-characterized Homo sapiens genes. Western blot analysis and RNA interference (RNAi) targeting HBx mRNA validated the overexpression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and Bcl-2 in L-O2-X cells. Meanwhile, the BrdU incorporation assay was used to test cell proliferation mediated by upregulated cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2).

Results:

The microarray showed that the expression levels of 152 genes were remarkably altered; 82 of the genes were upregulated and 70 genes were downregulated in L-O2-X cells. The altered genes were associated with signal transduction pathways, cell cycle, metastasis, transcriptional regulation, immune response, metabolism, and other processes. PCNA and Bcl-2 were upregulated in L-O2-X cells. Furthermore, we found that COX-2 upregulation in L-O2-X cells enhanced proliferation using the BrdU incorporation assay, whereas indomethacin (an inhibitor of COX-2) abolished the promotion.

Conclusion:

Our findings provide new evidence that HBx is able to regulate many genes that may be involved in the carcinogenesis. These regulated genes mediated by HBx may serve as molecular targets for the prevention and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, HBx, microarray, COX-2, proliferation

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is one of the major risk factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)1. However, the mechanism of HBV-induced HCC remains unclear2. The HBV genome is a partially double-stranded DNA molecule with four open reading frames (ORFs) termed S, C, P, and X3. The X gene of HBV (HBx) encodes a 154 amino acid polypeptide that is essential for viral infection and replication and plays a crucial role in the development of HCC4. Although HBx does not bind to DNA, it exerts a pleiotropic effect on diverse cellular functions as a transcriptional co-activator. HBx exhibits many activities in vitro. In a cell culture system, HBx is able to activate the transcription of host genes, such as c-Myc, as well as viral genes5, 6. HBx is also involved in different cytoplasmic signaling pathways. The majority of HBx is localized in the cytoplasm, where it interacts with and stimulates protein kinases such as protein kinase C, Janus kinase/STAT, IKK, PI-3-K, stress-activated protein kinase/Jun N-terminal kinase, and protein kinase B/Akt. HBx induces centrosome hyperamplification and mitotic aberration by activation of the Ras-MEK-MAPK pathway, which may contribute to genomic instability during hepatocarcinogenesis7. HBx can transactivate various cellular transcriptional elements, such as AP-1, AP-2, NF-κB, and cAMP response element (CRE) sites. Consequently, HBx can affect the activities of various transcriptional elements in the host cell and elicit different cellular responses. Previously, we demonstrated that HBx upregulated both the expression and the activity of hTERT in hepatoma8. We also found that HBx was able to upregulate the expression of survivin, which suggests that survivin may be involved in the carcinogenesis of HCC that is mediated by HBx9. cDNA microarray is a powerful tool for identifying disease-related gene expression profiles in biological samples. Using cDNA microarray, we examined gene expression profiles in a model of hepatoma cells stably transfected with HBx10. These data from the hepatoma cell model showed progressive changes during tumor development. However, the mechanism of hepatoma mediated by HBx remains unclear.

In the present study, we examined the gene expression profiles of L-O2-X cells by cDNA microarray analysis. When compared with the gene expression profiles of H7402-X cells10, our findings provide new insight into the molecular mechanism of carcinogenesis mediated by HBx in human liver cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human liver L-O2 cell line (purchased from Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co Ltd, Nanjing, China), which originated histologically from normal human liver tissue that had been immortalized by stable transfection of the hTERT gene, was used previously9, 11, 12, 13. L-O2-P (cell line from L-O2 cells stably transfected with empty pcDNA3 plasmid) and L-O2-X (cell line from L-O2 cells stably transfected with the HBx gene) were established as described previously13. L-O2, L-O2-P, and L-O2-X cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO, USA) containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 10% fetal calf serum. Cultures were incubated in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Gene expression profiling analysis

An Agilent 22 K human 70-mer oligonucleotide microarray (CapitalBio Corp, China) containing more than 21 329 unique, well-characterized Homo sapiens genes was used. Double-stranded cDNAs (containing the T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence) were synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the CbcScript reverse transcriptase with cDNA synthesis system according to the manufacturer's protocol (CapitalBio Corp, China) with the T7 Oligo (dT). cDNA labeled with a fluorescent dye (Cy5 or Cy3-dCTP) was produced by Eberwine's linear RNA amplification method and the subsequent enzymatic reaction and was improved by CapitalBio. The Klenow enzyme labeling strategy was adopted after reverse transcription using CbcScript II reverse transcriptase. All procedures for hybridization and slide and image processing were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. The slides were washed, dried, and scanned using a confocal LuxScan™scanner and the obtained images were then analyzed using LuxScan™ 3.0 software (both from CapitalBio Corp, China). The procedures were repeated for a replicate experiment with independent hybridization and processing. For individual channel data extraction, faint spots for which the intensities were below 400 units after background subtraction in both channels (Cy3 and Cy5) were removed. A space- and intensity-dependent normalization based on a LOWESS program was employed. To avoid false positive results, multiple testing corrections were considered. In each experiment, three types of positive controls (Hex, four housekeeping genes, and eight yeast genes) and two types of negative controls (50% DMSO and twelve negative control sequences from the Operon Oligo database) were used. Each probe was printed in triplicate. Furthermore, we performed the fluorescence-exchange microarray analysis. We performed three independent cDNA microarray experiments to obtain more precise data. For two-color designs, intensity reproducibility was calculated both within and across the two different dyes to assess the impact of the dye on the resulting measurement. For within-dye calculations, the technical replicates of samples labeled with the same dye across the microarrays were considered, and for across-dyes calculations, all replicates for a given sample labeled with either dye were evaluated. Comparisons between the combinations of P values and fold-change thresholds were given, with the differentially expressed genes identified using a one-sample t-test of the sample B to sample A (B/A) ratio data, including five replicates for each site. Two P values (P<0.05 and P<0.01) and three fold-change (FC) thresholds (FC>1.5, FC>2.0 and FC>4.0) were acceptable in the microarray analysis.

RNA interference

The HBV X gene was cloned into pSilencer 3.0 to create pSilencer 3.0-X. The following primers were used: sense, 5′-GATCCCGGTCTTACATAAGAGGACTTTCAAGA GAAGTCCTCTTATGTAAGACCTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ antisense, 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAAGGTCTTACATAAGAGGAC TTCTCTTGAAAGTCCTCCTTATGTAAGACCGGG-3′ 9. The purified vector was transfected using Lipofectamine into L-O2-X cells for 36 h, as described previously9. The expression level of the HBx protein in L-O2-X cells was examined by Western blot analysis.

Treatment with an inhibitor of COX-2

According to the data, we found that the PTGS2 gene was upregulated in L-O2-X cells (Table 1). The PTGS2 gene encodes COX-214. Therefore, we investigated the effect of HBx on COX-2 using an inhibitor of COX-2. The L-O2, L-O2-P, and L-O2-X cells were cultured as described above in a 6-well plate for 24 h, and then the cells were re-cultured in serum free medium for 12 h. Briefly, L-O2-X cells were treated with 50 μmol/L indomethacin (indo, Sigma-Aldrich, USA, inhibitor of COX-2) for 2 h. The level of COX-2 in the treated L-O2 cells was examined by Western blot analysis. Meanwhile, the proliferation of L-O2-X cells treated with indo was examined by the BrdU incorporation assay.

Table 1. Gene expression profiles in L-O2-X cells compared with L-O2 cells by cDNA microarray. Each probe was printed in triplicate using a SmartArray™ microarrayer (CapitalBio Corp Beijing, China) in every slide. cDNA microarray was the fluorescence-exchange microarray. Three independent cDNA microarray analysis were performed.

| Accession No | Abbreviation | Up-or down-regulation | Ratio1 | Ratio2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle | ||||

| CR616879 | CCNA1 | ↑ | 3.0672 | 3.0644 |

| U03106 | CDKN1A | ↓ | 0.2809 | 0.2452 |

| CAG46598 | PCNA | ↑ | 2.7062 | 2.4293 |

| Apoptosis | ||||

| BC008678 | IL1B | ↓ | 0.4557 | 0.4570 |

| NM_001191 | BCL2L1 | ↑ | 2.8732 | 3.0117 |

| Signaling pathway | ||||

| BC023523 | *DGKA | ↓ | 0.4739 | 0.4493 |

| BC026331 | *ITPKA | ↓ | 0.4398 | 0.5029 |

| Y11312 | #PIK3C2B | ↑ | 2.3524 | 2.2097 |

| U15932 | *DUSP5 | ↓ | 0.4698 | 0.5024 |

| BX640908 | *EVI1 | ↑ | 2.2908 | 3.6488 |

| BC036092 | *MAX | ↑ | 2.0580 | 2.1085 |

| L11285 | #MAP2K2 | ↑ | 2.4983 | 2.7410 |

| BC037236 | *DUSP6 | ↓ | 0.3693 | 0.4193 |

| U67206 | #CASP7 | ↓ | 0.4484 | 0.4970 |

| AY054395 | *BDNF | ↑ | 2.4910 | 2.1162 |

| M68874 | #PLA2G4A | ↑ | 2.4025 | 2.5646 |

| X52479 | #PRKCA | ↑ | 5.2584 | 5.5842 |

| Y10256 | #MAP3K14 | ↑ | 2.2107 | 2.1948 |

| CR612719 | *GADD45A | ↓ | 0.3957 | 0.1692 |

| CR618407 | BMP2 | ↓ | 0.3782 | 0.4479 |

| M34057 | *LTBP1 | ↑ | 2.0486 | 2.3859 |

| S78825 | ID1 | ↓ | 0.4211 | 0.5100 |

| M31682 | *INHBB | ↑ | 2.3259 | 2.0402 |

| AF048722 | *PITX2 | ↓ | 0.4366 | 0.4842 |

| L38969 | *THBS3 | ↑ | 2.6254 | 2.3153 |

| BC027958 | *BMP5 | ↑ | 27.3978 | 14.6852 |

| CR749295 | *BTRC | ↓ | 0.4133 | 0.5503 |

| AY009401 | #WNT6 | ↑ | 2.2685 | 2.2062 |

| AF016507 | *CTBP2 | ↑ | 2.5090 | 2.4220 |

| AB027464 | #FZD10 | ↑ | 2.1476 | 2.2260 |

| AL110263 | *PDE1A | ↓ | 0.0585 | 0.0036 |

| CR541865 | *TNNC1 | ↑ | 4.7137 | 3.2209 |

| AK090868 | *GNAL | ↑ | 4.6538 | 2.9530 |

| J04164 | *IFITM1 | ↓ | 0.2604 | 0.3697 |

| AK000507 | *DDIT4 | ↓ | 0.2913 | 0.3634 |

| U36798 | *PDE3A | ↑ | 2.9651 | 2.4967 |

| Leukocyte transendothelial migration | ||||

| AL832088 | MMP2 | ↓ | 0.1769 | 0.1513 |

| Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | ||||

| Q99706 | *KIR2DL4 | ↑ | 3.1394 | 2.6300 |

| BC034689 | *ULBP2 | ↓ | 0.4308 | 0.4985 |

| BC035416 | *ULBP1 | ↑ | 2.3254 | 2.3926 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | ||||

| AF020351 | *NDUFS4 | ↓ | 0.3385 | 0.4096 |

| Transport | ||||

| U49248 | *ABCC2 | ↑ | 2.4615 | 3.0030 |

| X78338 | *ABCC1 | ↑ | 2.3313 | 3.4222 |

| Interaction | ||||

| X03168 | *VTN | ↑ | 2.3919 | 2.0326 |

| BC066552 | *LAMA4 | ↑ | 2.7738 | 2.0726 |

| NM_002985 | *CCL5 | ↑ | 2.3735 | 2.5161 |

| J03171 | *IFNAR1 | ↑ | 2.7647 | 2.2603 |

| L08096 | *TNFSF7 | ↓ | 0.3164 | 0.3183 |

| X04430 | IL6 | ↑ | 2.0441 | 2.0289 |

| L04270 | *LTBR | ↓ | 0.5413 | 0.4026 |

| BC047698 | *IL7 | ↑ | 2.6382 | 3.6129 |

| U31628 | *IL15RA | ↑ | 2.1865 | 1.9884 |

| BC030155 | *TNFRSF11B | ↓ | 0.3813 | 0.4669 |

| CR602522 | *EDN1 | ↑ | 3.8264 | 3.6028 |

| BC035618 | *SSTR1 | ↑ | 2.7734 | 2.7338 |

| BC034393 | *EDN2 | ↑ | 3.2057 | 1.6309 |

| Cell adhesion | ||||

| AB000712 | *CLDN4 | ↑ | 3.0259 | 3.0188 |

| AB037787 | *NLGN2 | ↓ | 0.4008 | 0.4931 |

| AK075334 | *MPZL1 | ↑ | 2.0453 | 2.3812 |

| AJ011497 | *CLDN7 | ↓ | 0.2295 | 0.2684 |

| AF125377 | *SNAI1 | ↓ | 0.4816 | 0.4511 |

| X02761 | *FN1 | ↓ | 0.0503 | 0.0659 |

| AK001655 | *PARVA | ↑ | 2.5954 | 1.9570 |

| AF070648 | *CAV1 | ↓ | 0.2474 | 0.3467 |

| BC005256 | *CAV2 | ↓ | 0.4596 | 0.2935 |

| BX641139 | *SHC3 | ↓ | 0.4779 | 0.4600 |

| Cell Communication | ||||

| AK056254 | *KRT4 | ↑ | 4.8146 | 3.3134 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | ||||

| BC000114 | *MATK | ↓ | 0.3410 | 0.4210 |

| BC036756 | *GNA13 | ↓ | 0.4721 | 0.4635 |

| BF965156 | RRAS | ↓ | 0.4435 | 0.4023 |

| M59911 | *ITGA3 | ↓ | 0.4539 | 0.4284 |

| AK125819 | *GSN | ↓ | 0.3614 | 0.2474 |

| X06256 | ITGA5 | ↓ | 0.3154 | 0.3152 |

| D45906 | *LIMK2 | ↓ | 0.3485 | 0.2934 |

| X53587 | *ITGB4 | ↓ | 0.3316 | 0.3682 |

| AK026977 | *MYH10 | ↑ | 2.2017 | 2.4169 |

| AL096719 | *PFN2 | ↑ | 2.2427 | 2.7714 |

| X17033 | *ITGA2 | ↓ | 0.2675 | 0.2783 |

| Metabolism | ||||

| AK127770 | *PDE9A | ↓ | 0.3546 | 0.5053 |

| X02994 | *ADA | ↓ | 0.4653 | 0.4197 |

| D12485 | *ENPP1 | ↑ | 2.5975 | 1.6024 |

| U67733 | *PDE2A | ↑ | 5.2929 | 3.2765 |

| BG682813 | *POLE4 | ↑ | 2.6344 | 1.7177 |

| X55740 | *NT5E | ↑ | 1.9939 | 2.5385 |

| AK123345 | *PKM2 | ↑ | 2.0849 | 2.2023 |

| AK074134 | *SLC27A3 | ↓ | 0.3055 | 0.3450 |

| D13643 | *DHCR24 | ↑ | 1.7296 | 2.5274 |

| D88308 | *SLC27A2 | ↑ | 2.7027 | 2.1881 |

| U34683 | *GSS | ↓ | 0.4683 | 0.4188 |

| X03674 | *G6PD | ↑ | 2.1507 | 2.5817 |

| L35546 | *GCLM | ↑ | 2.3915 | 3.9486 |

| CR614504 | *GSTM3 | ↑ | 2.3722 | 2.5401 |

| BC020744 | *AKR1C4 | ↑ | 4.6412 | 4.8338 |

| S70154 | *ACAT2 | ↓ | 0.0156 | 0.0041 |

| BC004102 | *ALDH3A1 | ↑ | 5.0622 | 5.3780 |

| AF030555 | *ACSL4 | ↓ | 0.4089 | 0.5404 |

| D13900 | *ECHS1 | ↓ | 0.4890 | 0.4808 |

| CR601714 | *ME1 | ↑ | 1.9955 | 2.1160 |

| AB031478 | *ACP6 | ↑ | 2.5841 | 2.1902 |

| AK025732 | *ASAH1 | ↑ | 2.1362 | 2.0824 |

| BC070060 | *SGPP1 | ↑ | 2.6498 | 1.7846 |

| AK095578 | *SPHK1 | ↓ | 0.2473 | 0.2105 |

| M15856 | *LPL | ↑ | 8.8089 | 12.5624 |

| M57892 | *CA6 | ↑ | 2.1346 | 3.0340 |

| D90282 | *CPS1 | ↑ | 2.2087 | 2.8370 |

| M12267 | *OAT | ↓ | 0.0393 | 0.1207 |

| BC011831 | *MMAB | ↑ | 2.4665 | 1.6824 |

| D63391 | *PAFAH1B3 | ↓ | 0.5393 | 0.4115 |

| BC001482 | *PISD | ↓ | 0.4591 | 0.5443 |

| AF523360 | *HNMT | ↑ | 3.3276 | 2.2063 |

| M61831 | *AHCY | ↓ | 0.4089 | 0.3775 |

| U89942 | LOXL2 | ↑ | 1.9654 | 2.1514 |

| AK131096 | *GALNS | ↓ | 0.4241 | 0.5482 |

| U03056 | *HYAL1 | ↓ | 0.2634 | 0.5182 |

| BC014139 | *ALPPL2 | ↓ | 0.2423 | 0.5194 |

| BC009647 | *ALPP | ↑ | 2.0290 | 2.3588 |

| M62783 | *NAGA | ↓ | 0.2378 | 0.3437 |

| U12778 | *ACADSB | ↓ | 0.4079 | 0.4722 |

| BC017338 | *FUCA1 | ↓ | 0.4378 | 0.3032 |

| AB016247 | *SC5DL | ↑ | 3.3849 | 3.2823 |

| AB015630 | *B3GNT3 | ↓ | 0.2042 | 0.2731 |

| AK095746 | *B3GNT4 | ↓ | 0.5518 | 0.4466 |

| BC017249 | *ENO3 | ↑ | 1.9912 | 2.6999 |

| D14697 | *FDPS | ↓ | 0.4835 | 0.4999 |

| AK096313 | *CARS | ↑ | 2.0912 | 2.1213 |

| X91257 | *SARS | ↑ | 2.1797 | 2.4608 |

| AK074524 | *GARS | ↑ | 1.9285 | 2.2692 |

| AK129934 | PCK2 | ↑ | 1.7061 | 2.7548 |

| NM_000963 | PTGS2 | ↑ | 3.4100 | 3.4133 |

| Hematopoietic cell lineage | ||||

| AK125531 | *CD24 | ↑ | 2.9598 | 2.3196 |

| M22324 | *ANPEP | ↓ | 0.2580 | 0.1899 |

| J03779 | *MME | ↓ | 0.3872 | 0.4473 |

| AK074082 | *EPOR | ↑ | 2.3909 | 2.4391 |

| Complement and coagulation cascades | ||||

| M14113 | *F8 | ↑ | 1.9940 | 2.5842 |

| M57729 | *C5 | ↑ | 3.3546 | 2.6310 |

| BX649164 | *SERPINE1 | ↓ | 0.1994 | 0.1417 |

| BC013575 | PLAU | ↓ | 0.3667 | 0.4330 |

| CR601067 | PLAUR | ↓ | 0.2728 | 0.2455 |

| J02931 | *F3 | ↑ | 2.5378 | 2.5057 |

| M14338 | *PROS1 | ↓ | 0.5346 | 0.4295 |

| BC005378 | *C4BPB | ↑ | 5.0472 | 4.1054 |

| Carbon fixation | ||||

| L12711 | *TKT | ↑ | 2.0682 | 2.2488 |

| Tight junction | ||||

| Z15108 | #PRKCZ | ↓ | 0.4353 | 0.4319 |

| AK025615 | *BCAT1 | ↑ | 4.2197 | 2.0964 |

| Long-term depression | ||||

| D26070 | *ITPR1 | ↑ | 3.6304 | 3.7319 |

| Axon guidance | ||||

| M57730 | *EFNA1 | ↑ | 2.4792 | 2.9131 |

| AF040990 | *ROBO1 | ↑ | 4.4963 | 2.7992 |

| CR749333 | *NRP1 | ↓ | 0.4256 | 0.5860 |

| Ribosome | ||||

| X69150 | *RPS18 | ↓ | 0.4647 | 0.3602 |

| Huntington's disease | ||||

| M55153 | *TGM2 | ↓ | 0.3356 | 0.2605 |

| Alzheimer's disease | ||||

| AF178532 | *BACE2 | ↓ | 0.3260 | 0.2350 |

| Neurodegenerative disorders | ||||

| AB020652 | *NEFH | ↓ | 0.1642 | 0.0152 |

Note: Genes marked * have not been reported to associate with HBx in literature. Genes marked # have been reported to indirectly associate with HBx in literature.

Western blot analysis

L-O2-X, L-O2-P, and L-O2 cells were lysed in protein lysis buffer (62.5 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol) and the protein concentration was determined using the 2-D Quant kit (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Following electro-transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, the membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in 0.1% Triton X 100-TBS (TTBS) and incubated overnight at 4°C with specific primary antibodies. The following primary antibodies were used as described previously9, 15: PCNA (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA, USA, 1:1000 dilution); Bcl-2 (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA, USA, 1:500 dilution); HBx (obtained from the Fox Chase Institute for Cancer Research, Philadelphia, Pa, USA, 1:50 000 dilution); COX-2 (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA, USA, 1:200 dilution); and β-actin (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA, USA, 1:1000 dilution). Staining was performed with an HRP-linked secondary antibody (GE Healthcare Bio-Science, USA). The protein bands were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit according to the manufacturer's specifications (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, USA).

BrdU incorporation assay

DNA synthesis was measured using a 5′-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma, USA) incorporation assay. Briefly, L-O2, L-O2-P, and L-O2-X cells were seeded in 24-well plates for 12 h, and then the cells were serum starved in defined medium overnight. Additionally, L-O2, L-O2-P, and L-O2-X cells were treated with 50 μmol/L indo for 4 h. The BrdU incorporation assay was performed according to a previously published protocol16. The BrdU labeling index was assessed by point counting through a Nikon TE200 inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using a 40×objective lens. A total of 700–800 nuclei were counted in 6–8 representative fields. The labeling index was expressed as the number of positively-labeled nuclei/total number of nuclei. All groups (n=3 in each group) were performed.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated independently, at least three times. Values are given as means±SD. The analyzed data from two groups were compared using Student's t test. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Differential expression profiles in L-O2-X cells

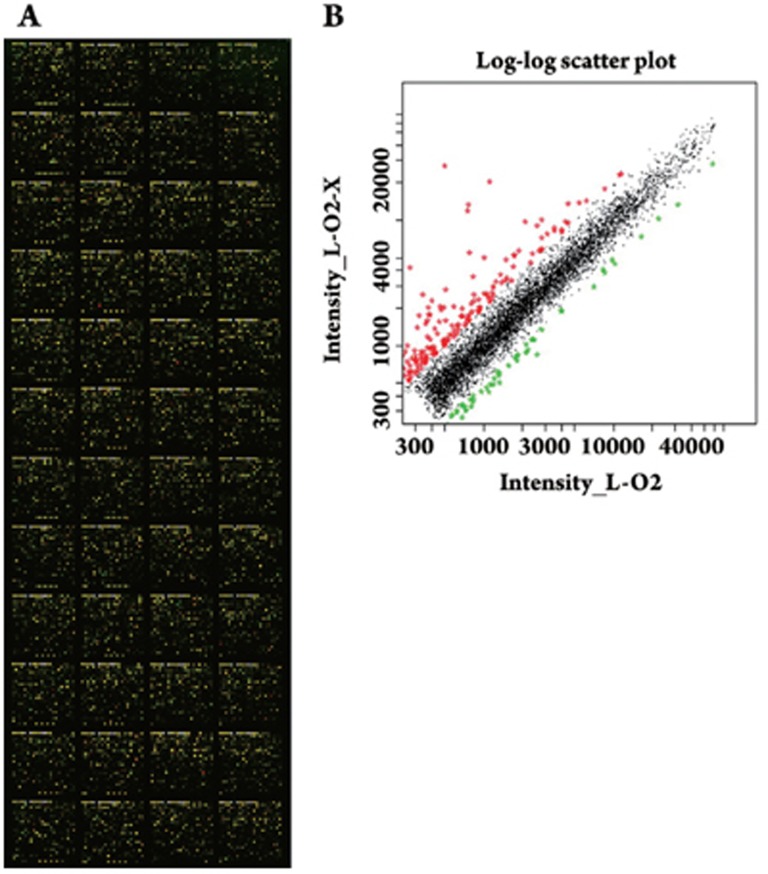

Previously, we investigated progressive changes in hepatoma cells stably transfected with HBx and found some differentially expressed genes10. However, those data only showed the distinctive gene pattern in the context of heptoma. To distinguish the differential expression of genes in normal human liver L-O2 cells and hepatoma cells mediated by HBx, we examined the differential expression profiles in L-O2-X cells by cDNA microarray analysis (Figure 1). The cDNA microarray showed that the expression levels of 152 genes were remarkably altered, 82 of those genes were upregulated and 70 genes were downregulated in the L-O2-X cells. The altered genes were associated with signal transduction pathways, cell cycle, metastasis, transcriptional regulation, immune response, metabolism, and other processes (Table 1). To avoid false positive results, each probe was printed in triplicate using a SmartArray™ microarrayer (CapitalBio Corp Beijing, China). The cDNA microarray used was the fluorescence-exchange microarray. Additionally, we performed three independent cDNA microarray analyses to get more precise data. In Table 1, the expression of the selected candidates was either up- or down-regulated by at least two folds. When compared with the differential expression profiles in H7402-X cells10, we found that the data from the differential expression profiles in L-O2-X cells differed substantially. Only three genes, PCNA, BMP2, and IL-6, were altered in both H7402-X cells and L-O2-X cells.

Figure 1.

Examination of the L-O2-X gene expression profiles by cDNA microarray analysis. (A) A scanning image of the hybridizing signals on gene chips showed high expression (red), low expression (green), and no expression changes (yellow) between L-O2 and L-O2-X cells. (B) Scatter plot graph of Cy3-labeled and Cy5-labeled probes hybridizing with the microarray. Each point on the plot represented a gene hybridization signal. The black points represented ratios that ranged from 0.5 to 2.0 and belonged to the no difference group. The red points represented the ratios that were >2.0 and the green points represented the ratios that were <0.5, both of which indicate that gene expression was most probably altered.

HBx was responsible for the upregulation of PCNA and Bcl-2

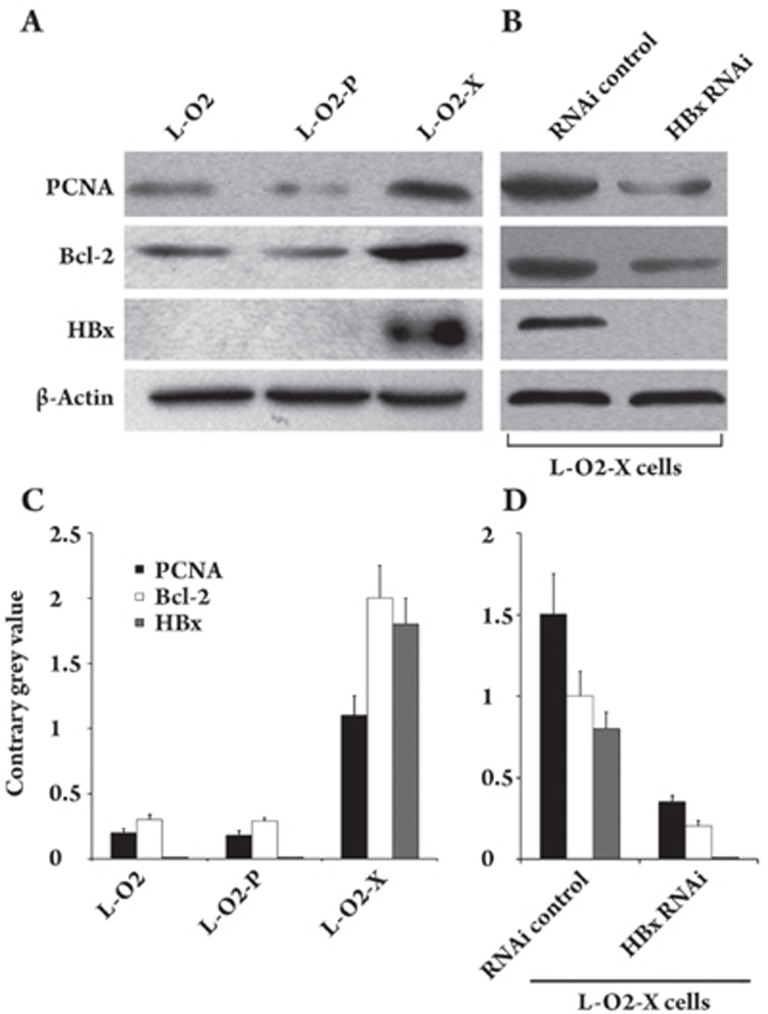

To further validate the candidate genes in the cDNA microarray and to preliminarily investigate the molecular alterations of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and Bcl-2 in the L-O2-X cell line, we examined the regulation of PCNA and Bcl-2 at the protein level by Western blot analysis. The data showed that the expression levels of PCNA and Bcl-2 were increased in L-O2-X cells (Figure 2A). We further confirmed the findings by applying Glyco BandScan software (PROZYME, San Leandro, CA, USA; Figure 2C). Moreover, we investigated the effect of HBx on the regulation of PCNA and Bcl-2 by RNA interference (RNAi) targeting HBx mRNA. After transfection, the RNAi resulted in the decrease of PCNA and Bcl-2 within 48 h (Figure 2B), suggesting that HBx was responsible for the upregulation of PCNA and Bcl-2. These data were further confirmed by Glyco BandScan software (PROZYME, San Leandro, CA, USA; Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

HBx upregulated the expression of PCNA and Bcl-2. (A) Western blot analysis showed that the expression levels of PCNA and Bcl-2 were upregulated in L-O2-X cells. HBx was detectable in L-O2-X cells. (B) PCNA, Bcl-2 and HBx protein were downregulated by transfection with pSilencer 3.0-X plasmid encoding silencing RNA, which targets HBx mRNA in L-O2-X cells. (C, D) The histogram shows the results from applying Glyco Band-Scan software.

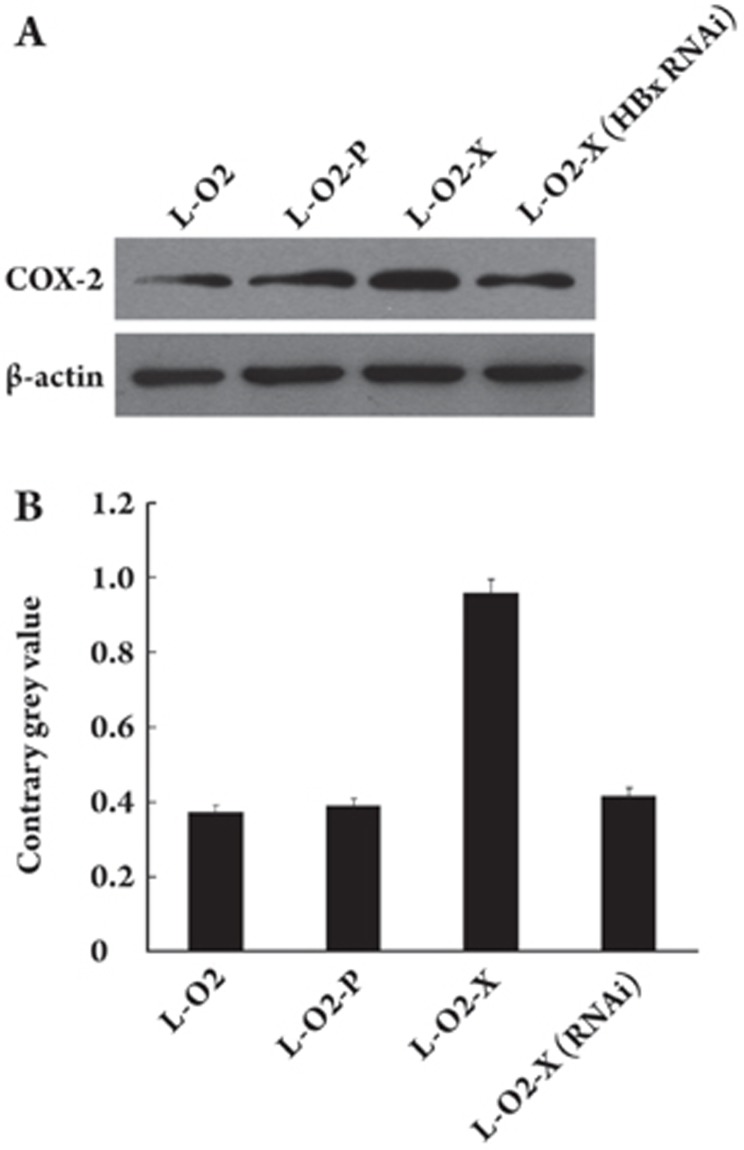

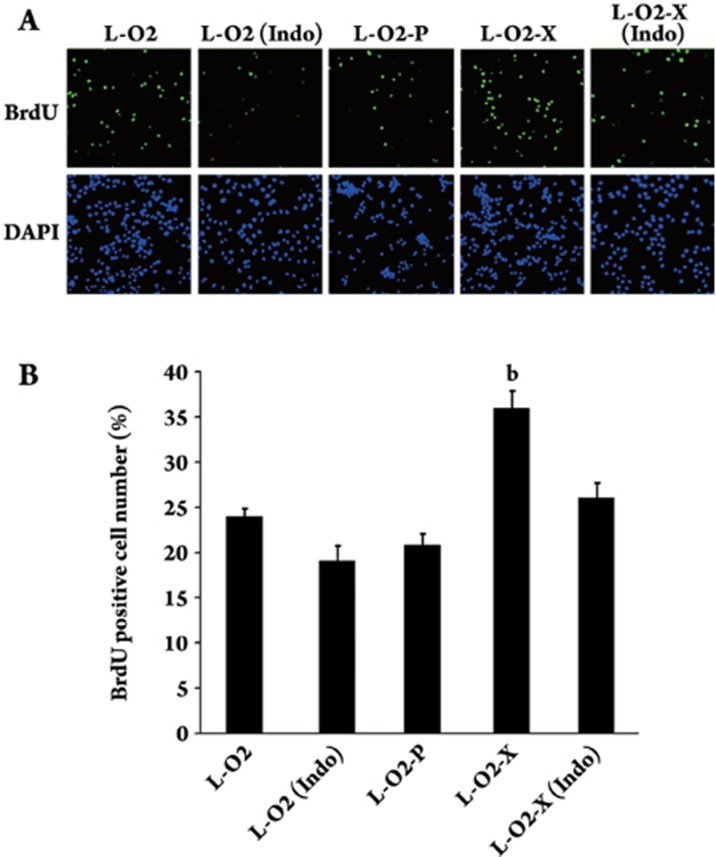

The upregulation of COX-2, mediated by HBx, contributed to the proliferation

As shown in Table 1, the COX-2 gene was upregulated in L-O2-X cells. We provided evidence by Western blot analysis that the expression of COX-2 at the protein level was higher in L-O2-X cells than in L-O2 cells (Figure 3A). The downregulation of HBx mediated by RNAi in L-O2-X cells abolished the upregulation of COX-2 (Figure 3A). We further confirmed the findings by applying Glyco BandScan software (PROZYME, San Leandro, CA, USA; Figure 3B). Next, we demonstrated the effect of COX-2 on proliferation using the BrdU incorporation assay. The data showed that the percentage of cells in the S phase significantly increased in L-O2-X cells (P<0.05, vs L-O2 cells, Student's t test). However, enhanced proliferation in L-O2-X cells was abolished by treatment with indomethacin (indo, an inhibitor of COX-2, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) (Figure 4), suggesting that HBx was able to upregulate COX-2, which contributed to the proliferation. No statistically significant difference was observed between L-O2 cells and cells transfected with empty pcDNA3 vector (termed L-O2-P).

Figure 3.

HBx was responsible for the upregulation of COX-2, as indicated by Western blotting. (A) COX-2 was upregulated in L-O2-X cells. Transfection with the pSilencer 3.0-X plasmid encoding silencing RNA, which targets HBx mRNA, could abolish the tendency. (B) The histogram shows the results of applying Glyco Band-Scan software.

Figure 4.

The upregulation of COX-2, mediated by HBx, contributed to proliferation and is shown by BrdU incorporation assay. Positive DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride hydrate, Sigma) staining was shown by blue fluorescence in the nuclei of cells. Green fluorescence showed the number of BrdU positive cells. (A) The BrdU incorporation assay showed that proliferation was higher in the L-O2-X cells relative to L-O2 cells (bP<0.05, L-O2-X vs L-O2 cells, Student's t test). (B) The histogram represents three independent experiments with standard errors, shown as error bars.

Discussion

HBx plays a crucial role in HBV-related pathogenesis. Some research groups have investigated the gene expression profiles associated with HBx. However, our data differ markedly from that data in these reports17, 18. HBx can lead to contradictory findings, largely because of the use of different cell types and transformed cells. In the present study, we chose an immortalized human liver cell line as a model to show the basic response of host cells to the HBx gene.

Using a cDNA microarray technique, we identified and classified the genes that were altered as a result of their involvement in an HBx-mediated process (Figure 1). Our findings showed that 82 genes were upregulated and 70 genes were downregulated in L-O2-X cells (Table 1). Most were involved in the cell cycle, signal pathways, metastasis, immune response, metabolism, and other processes. Table 1 shows that many genes that have not been reported to associate with HBx in the literature were found by microarray assay, which provides us with valuable clues for the further investigation of HBx. Our data showed that cyclin A1, PCNA and Bcl-2 were upregulated, whereas p21 was simultaneously downregulated. Furthermore, the altered expression of PCNA and Bcl-2 was verified by Western blot analysis (Figure 2). HBx upregulates PCNA by increasing the recruitment of CBP/p300 to endogenous PCNA promoters19. Our microarray data were consistent with this report. Cyclin A1, a member of the cyclin A family, is related to some types of carcinogenesis20. p21 is a negative regulator of the cell cycle. BCL-2 family members form hetero- or homodimers and act as anti- or pro-apoptotic regulators that are involved in a wide variety of cellular activities. Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) play important roles in controlling cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Defects in cell cycle regulation are common causes of the abnormal proliferation of cancer cells. Those proteins, which are mentioned above and are involved in the cell cycle and apoptosis, may greatly influence tumorigenesis. Another study indicates that many MAPK family members are upregulated in HBV-related HCC10, 21. Our present data showed that MAP2K2, MAP3K14 and MAX were upregulated, whereas Gadd45a was downregulated in L-O2-X cells; these changes may be related to rapid proliferation. All biological activities of c-Myc require its binding partner, Max22. c-Myc has been assigned roles in hepatocyte proliferation during liver development and regeneration, control of hepatic metabolism, and the dysregulated growth that occurs during heptocarcinogenesis23, 24, 25, 26. Therefore, the enhancement of Max may be consistent with the induction of c-Myc in L-O2-X cells to promote hepatocyte growth and proliferation. In our experiments, Gadd45a, a p53-regulated and DNA damage inducible protein, was downregulated. Gadd45 plays a role in G2-M arrest in response to DNA damage. Gadd45 can bind to multiple important cellular proteins such as PCNA, p21 protein, MTK/MEKK4 — an upstream activator of the JNK pathway — and Cdc2 protein kinase. Furthermore, some reports show that Gadd45 can inhibit cell transformation and tumor progression27, 28. Signaling by the Wnt family of secreted glycoproteins is essential both in normal embryonic cell-to-cell interactions and in the pathogenesis of a variety of diseases, including cancer29. First, Wnt proteins bind to receptors of the Frizzled and LRP families on the cell surface. Then, through several cytoplasmic relay components, the signal is transduced to activate transcription of Wnt target genes. Here, we found that both FZD10 (one of the Frizzled and LRP families) and CTBP2, which are involved in Wnt signaling, were increased. Additionally, BTRC, which may be a candidate for tumor-suppressive activities30, was decreased in L-O2-X cells. Indeed, RNA interference-mediated knockdown of CtBP2 (C-terminal binding protein family proteins) decreases cell invasion, and ectopic expression of CtBP2 enhances tumor cell migration and invasion. Importantly, the overexpression of FZD10 (a cell-surface receptor for molecules in the Wnt pathway) acts as a potential contributor to synovial sarcomas. Moreover, a humanized antibody against FZD10 might be a promising treatment for patients with tumors that overexpress FZD1031. Secreted-type glycoprotein WNTs can bind to FZD10 to transduce signals to the β-catenin-TCF pathway, the JNK pathway, or the calcium signaling pathway. Accordingly, variation in the Wnt pathway and other signals affected by the Wnt pathway that were seen in our study may contribute to the early carcinogenesis mediated by HBx.

Interactions between cells and their surrounding extracellular matrix are essential for the proper execution and regulation of survival, proliferation, cytoskeletal organization, and migration. Furthermore, cell-extracellular matrix contact regulates physiological and pathological processes, such as development, differentiation, and metastasis. Laminins, a family of extracellular matrix glycoproteins, are the major noncollagenous constituents of the basement membrane. Some reports suggest that a strong correlation between the high expression of LAMA4 (one of laminin family) and tumor invasion and metastasis indicates that it is a novel marker for the processes of tumor invasion and metastasis32. Our microarray data showed that LAMA4 was upregulated in L-O2-X cells. The chemokine RANTES (regulated on activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted; CCL5) is a member of the CC-chemokine family, a group of small proteins with a highly conserved structure33. Using the cDNA microarray technique, we found that CCL5 was highly expressed in L-O2-X cells. Other studies indicate that CCL5s are inflammatory mediators with pro-malignancy activities in breast cancer and that they are shown to mediate many types of tumor-promoting cross-talk between the tumor cells and cells of the tumor microenvironment. Tumor-derived CCL5 can inhibit the T cell response and enhance the growth of murine mammary carcinoma in vivo34. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces either differentiation or growth of a variety of cells and also plays a role in cell interaction. In our study, IL-6 was upregulated in L-O2-X cells relative to L-O2 cells. Binding of IL-6 to its receptor initiates cellular events including activation of JAK kinases and activation of ras-mediated signaling. In addition, it has been suggested that IL-6 participates in the malignant progression of prostate cancer35. Adhesion of tumor cells to host cell layers and subsequent migration are pivotal steps in cancer invasion and metastasis. Organization of the cytoskeleton and cell adhesion molecules plays an important role in this event. Some candidates in our study were related to these cell processes, including CLDN4, CLDN7, CAV1, and CAV2. The family of more than 20 claudin (CLDN) proteins comprises one of the major structural elements within the apical tight junction apparatus, a dynamic cellular nexus for maintenance of a luminal barrier, paracellular transport, and signal transduction. Loss of normal tight junction functions constitutes a hallmark of human carcinomas. CLDN4 proteins are maintained or elevated in breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, whereas CLDN7 proteins are diminished in head, neck, and breast tumors36. The down-regulation of caveolin-1 (encoded by CAV1) and caveolin-2 (encoded by CAV2) is found in various types of primary tumors and cancer cell lines, indicating that these are candidate tumor suppressor genes37, 38.

In our data, we also found that HBx greatly affected cellular metabolism, in which HBx upregulated the PTGS2 gene that encodes cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (Figure 3). COX-2 is overexpressed in various cancers, including esophageal, gastric, colon, and pancreatic cancers39. It is possible that both tumor- and stroma-derived COX-2 could influence tumor proliferation, angiogenesis and/or immune function. Using the BrdU incorporation assay, we observed that HBx enhanced the proliferation of L-O2 cells by upregulating COX-2 (Figure 4). Our findings are concurrent with a report that HBx induces COX-2 through the activation of NF-AT to promote tumor cell invasion and metastasis40. LOXL2 catalyzes the crosslinking of collagen and elastin in the extracellular matrix and is assumed to be involved in tumor progress and cell adhesion. Some findings support the presumption that LOXL2 plays a role in malignant transformation41, 42.

In this study, we found that only three genes, PCNA, BMP2 and IL-6, were altered in both H7402-X cells and L-O2-X cells. We considered the possibility that HBx may affect gene expression in different ways in hepatoma H7402 cells and L-O2 liver cells because the genetic background is different. The gene expression profiles mediated by HBx in L-O2 cells may reflect alterations in the early stage of carcinogenesis.

Our study has revealed some novel candidate genes by cDNA microarray analysis (Table 2) that provide new insight into the pathogenesis mediated by HBx. Consequently, an understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in this dynamic process will aid in identifying novel potential targets for earlier diagnosis and more specific therapies.

Table 2. Genes significantly altered in L-02-X cells and their classifications in signal pathway.

| Accession No | Abbreviation | Up-ordown- regulation | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle | |||

| CR616879 | CCNA1 | ↑ | cyclin A1 |

| U03106 | CDKN1A | ↓ | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21, Cip1) |

| CAG46598 | PCNA | ↑ | proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| Apoptosis | |||

| NM_001191 | BCL2L1 | ↑ | Bcl2 interacting mediator 1 of cell death |

| Signaling pathway | |||

| MAPK signaling pathway | |||

| BC036092 | MAX | ↑ | MAX protein |

| L11285 | MAP2K2 | ↑ | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 2 |

| M68874 | PLA2G4A | ↑ | Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) |

| X52479 | PRKCA | ↑ | PKC-alpha |

| Y10256 | MAP3K14 | ↑ | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 14 |

| CR612719 | GADD45A | ↓ | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible protein GADD45 alpha |

| Wnt signaling pathway | |||

| CR749295 | BTRC | ↓ | beta-transducin repeat containing |

| AY009401 | WNT6 | ↑ | wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 6 |

| AF016507 | CTBP2 | ↑ | C-terminal binding protein 2 |

| AB027464 | FZD10 | ↑ | frizzled homolog 10 |

| Interaction | |||

| BC066552 | LAMA4 | ↑ | laminin, alpha 4 |

| NM_002985 | CCL5 | ↑ | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 |

| X04430 | IL6 | ↑ | interleukin 6 |

| Cell adhesion | |||

| AB000712 | CLDN4 | ↑ | claudin 4 |

| AJ011497 | CLDN7 | ↓ | claudin 7 |

| AF070648 | CAV1 | ↓ | Caveolin-1 |

| BC005256 | CAV2 | ↓ | Caveolin-2 |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | |||

| U89942 | LOXL2 | ↑ | Lysyl oxidase related protein 2 |

| NM_000963 | PTGS2 | ↑ | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

Author contributions

Prof Xiao-dong ZHANG and Li-hong YE designed the research; Wei-ying ZHANG performed the research; Prof Rong XIANG discussed the research; Fu-qing XU and Chang-liang SHAN help to perform part of the research. Wei-ying ZHANG analyzed the data and wrote the paper. Prof Xiao-dong ZHANG revised the paper.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, No 2007CB914802, No 2007CB914804, No 2009CB521702), Chinese State Key Projects for High-Tech 863 Program (2006AA02A247),and the National Natural Science Foundation (No 30670959).

References

- Zhang XD, Zhang WY, Ye LH. Pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. Future Virol. 2006;1:637–47. [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson MA, Sun B, Satiroglu Tufan NL, Liu J, Pan J, Lian Z. Genetic mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:2593–604. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda K. Hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2000;32:225–37. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XD, Zhang H, Ye LH. Effects of hepatitis B virus X protein on the development of liver cancer. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkler FF, Koshy R. Hepatitis B virus transcriptional activators: mechanisms and possible role in oncogenesis. J Viral Hepat. 1996;3:109–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.1996.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su JM, Lai XM, Lan KH, Li CP, Chao Y, Yen SH, et al. X protein of hepatitis B virus functions as a transcriptional corepressor on the human telomerase promoter. Hepatology. 2007;46:402–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.21675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun C, Cho H, Kim SJ, Lee JH, Park SY, Chan GK, et al. Mitotic aberration coupled with centrosome amplification is induced by hepatitis B virus X oncoprotein via the Ras-mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen- activated protein pathway. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:159–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XD, Dong N, Zhang H, You JC, Wang HH, Ye LH. Effects of hepatitis B virus X protein on human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression and activity in hepatoma cells. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;145:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XD, Dong N, Yin LH, Cai N, Ma HT, You JC, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein upregulates survivin expression in hepatoma tissues. J Med Virol. 2005;77:374–81. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye LH, Dong N, Wang Q, Xu ZL, Cai N, Wang HH, et al. Progressive changes in hepatoma cells stably transfected with hepatitis B virus X gene. Intervirology. 2008;51:50–8. doi: 10.1159/000120289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Xing Z, Luan Z, Wu T, Wu X, Hu G. A specific splicing variant of SVH, a novel human armadillo repeat protein, is up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3775–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Wu T, Xu L, Liu A, Ji Y, Hu G. Upstream binding factor up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma is related to the survival and cisplatin-sensitivity of cancer cells. FASEB J. 2002;16:293–301. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0687com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Shan CL, Li N, Zhang X, Zhang XZ, Xu FQ, et al. Identification of a natural mutant of HBV X protein truncated 27 amino acids at the COOH terminal and its effect on liver cell proliferation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:473–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YD, Chen WD, Wang M, Yu D, Forman BM, Huang W. Farnesoid X receptor antagonizes nuclear factor kappaB in hepatic inflammatory response. Hepatology. 2008;48:1632–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.22519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang FZ, Sha L, Ye LH, Zhang XD. Promotion of cell proliferation by HBXIP via upregulation of human telomerase reverse transcriptase in human mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:83–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengronne A, Pasero P, Bensimon A, Schwob E. Monitoring S phase progression globally and locally using BrdU incorporation in TK (+) yeast strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1433–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng RK, Lau CY, Lee SM, Tsui SK, Fung KP, Waye MM. cDNA microarray analysis of early gene expression profiles associated with hepatitis B virus X protein-mediated hepatocarcinogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:827–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Zhang Z, Kim JW, Huang Y, Liang TJ. Altered proteolysis and global gene expression in hepatitis B virus X transgenic mouse liver. J Virol. 2006;80:1405–13. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1405-1413.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Pezzi E, Gómez-Gaviro MV, Gálvez BG, Mira E, Iñiguez MA, Fresno M, et al. The hepatitis B virus X protein promotes tumor cell invasion by inducing membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 expression. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1831–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI200215887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng KY, Noble ME, Skamnaki V, Brown NR, Lowe ED, Kontogiannis L, et al. The role of the phospho-CDK2/cyclinA recruitment site in substrate recognition. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23167–79. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XR, Huang J, Xu ZG, Qian BZ, Zhu ZD, Yan Q, et al. Insight into hepatocellular carcinogenesis at transcriptome level by comparing gene expression profiles of hepatocellular carcinoma with those of corresponding noncancerous liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15089–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241522398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood EM, Luscher B, Eisenman RN. Myc and max associate in vivo. Genes Dev. 1992;6:71–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier JJ, Doan TT, Daniels MC, Shurr JR, Kolls JK, Scott DK. c-Myc is required for the glucose-mediated induction of metabolic enzyme genes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6588–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Li Q, Dang CV, Lee LA. Induction of ribosomal genes and hepatocyte hypertrophy by adenovirus-mediated expression of c-Myc in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11198–202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200372597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riu E, Ferre T, Mas A, Hildago A, Franckhauser S, Bosch F. Overexpression of c-myc in diabetic mice restores altered expression of the transcription factor genes that regulate liver metabolism. Biochem J. 2002;368:931–7. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson NL, Mead JE, Braun L, Goyette M, Shank PR, Fausto N. Sequential protooncogene expression during rat liver regeneration. Cancer Res. 1986;46:3111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji JF, Wu Y, Zhan Q. Gadd45a function in suppressing cell transformation and tumor malignancy. Prog Biochem Biophys. 2006;12:1146–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q, Lord KA, Alamo IJ, Hollander MC, Carrier F, Ron D, et al. The gadd and MyD genes define a novel set of mammalian genes encoding acidic proteins that synergistically suppress cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2361–71. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R. Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res. 2005;15:28–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Suzuki M, Tanigami A, Ikenoue T, Omata M, Chiba T, et al. The BTRC gene, encoding a human F-box/WD40-repeat protein, maps to chromosome 10q24-q25. Genomics. 1999;58:104–5. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama S, Fukukawa C, Katagiri T, Okamoto T, Aoyama T, Oyaizu N, et al. erapeutic potential of antibodies against FZD10, a cell-surface protein, for synovial sarcomas. Oncogene. 2005;24:6201–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Ji G, Wu Y, Wan B, Yu L. LAMA4, highly expressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma from Chinese patients, is a novel marker of tumor invasion and metastasis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:705–14. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnik A, Yoshie O. Chemokines: a new classification system and their role in immunity. Immunity. 2000;12:121–7. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner JW, Uchida O, Kajiwara N, Kim EY, Patel AC, O'Sullivan MP, et al. CCL5-CCR5 interaction provides antiapoptotic signals for macrophage survival during viral infection. Nat Med. 2005;11:1180–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PC, Hobish A, Lin D L, Culig Z, Keller ET. Interleukin-6 and prostate cancer progression. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kominsky SL, Argani P, Korz D, Evron E, Raman V, Garrett E, et al. Loss of the tight junction protein claudin-7 correlates with histological grade in both ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Oncogene. 2003;22:2021–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiechen K, Diatchenko L, Agoulnik A, Scharff KM, Schober H, Arlt K, et al. Caveolin-1 is down-regulated in human ovarian carcinoma and acts as a candidate tumor suppressor gene. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1635–43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiucci G, Ravid D, Reich R, Liscovitch M. Caveolin-1 inhibits anchorage independent growth, anoikis and invasiveness in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:2365–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga T, Shibahara K, Kabashima A, Sumiyoshi Y, Kimura Y, Takahashi I, et al. Altered proteolysis and global gene expression in hepatitis B virus X transgenic mouse liver Hepatogastroenterology 2004511626–30.15532792 [Google Scholar]

- Cougot D, Wu Y, Cairo S, Caramel J, Renard CA, Lévy L, et al. The hepatitis B virus X protein functionally interacts with CREB-binding protein/p300 in the regulation of CREB-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4277–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost T, Pyritz V, Rathcke IO, Görögh T, Dünne AA, Werner JA. Reduction of LOX- and LOXL2-mRNA expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:1565–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Semjonow A, Csiszar K, Korsching E, Brandt B, Eltze E. Mapping of a deletion interval on 8p21–22 in prostate cancer by gene dosage PCR. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 2007;91:302–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]