Abstract

Introduction

Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is one of the most common complications after cardiac surgery. Patients who develop POAF have a prolonged stay in the intensive care unit and hospital and an increased risk of postoperative stroke. Many guidelines for the management of cardiac surgery patients, therefore, recommend perioperative administration of beta-blockers to prevent and treat POAF. Landiolol is an ultra-short acting beta-blocker, and some randomized controlled trials of landiolol administration for the prevention of POAF have been conducted in Japan. This meta-analysis evaluated the effectiveness of landiolol administration for the prevention of POAF after cardiac surgery.

Methods

The Medline/PubMed and BioMed Central databases were searched for randomized controlled trials comparing cardiac surgery patients who received perioperative landiolol with a control group (saline administration, no drug administration, or other treatment). Two independent reviewers selected the studies for inclusion. Data regarding POAF and safety outcomes were extracted. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Mantel–Haenszel method (fixed effects model).

Results

Six trials with a total of 560 patients were included in the meta-analysis. Landiolol administration significantly reduced the incidence of POAF after cardiac surgery (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.17–0.40). The effectiveness of landiolol administration was similar in three groups: all patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.17–0.43), patients who underwent CABG compared with a control group who received saline or nothing (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.17–0.45), and all patients who underwent cardiac surgery compared with a control group who received saline or nothing (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.17–0.42). Only two adverse events associated with landiolol administration were observed (2/302, 0.7%): hypotension in one patient and asthma in one patient.

Conclusion

Landiolol administration reduces the incidence of POAF after cardiac surgery and is well tolerated.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0116-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Beta-blocker, Cardiac surgery, Cardiology, Landiolol, Meta-analysis, Perioperative

Introduction

Although perioperative administration of beta-blockers is recommended in high-risk non-cardiac patients, routine administration of high-dose beta-blockers is not recommended in the absence of dose titration [1]. In cardiac surgery patients, beta-blockers should be administered perioperatively to all patients without contraindications to reduce the incidence and clinical sequelae of postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) [2–4].

Postoperative atrial fibrillation is one of the most common complications after cardiac surgery and is associated with postoperative stroke, prolonged stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital, and increased hospital costs [2–6]. Most guidelines for the management of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, including the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery [2], Canadian Cardiovascular Society Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines [3], and European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery/European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions Guidelines for Myocardial Revascularization [4], recommend perioperative administration of beta-blockers to prevent and treat POAF. As continuous administration during the high-risk period is necessary to prevent POAF, the ACCF/AHA guideline recommends preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative administration of beta-blockers [2]. However, many studies of the efficacy of beta-blocker therapy used oral administration, and the effectiveness of intravenous beta-blocker administration for the prevention of POAF remains unclear.

Landiolol hydrochloride, which is launched in Japan, is an ultra-short-acting beta-blocker with a very short half-life of approximately 4 min, a high beta1/beta2 selectivity ratio of about 255, and less of a negative inotropic effect than esmolol, which provides a response at 0–2 min after administration [7–11]. The selectivity ratio of landiolol is higher than other beta blockers, such as bisoprorol (13.5), atenolol (4.7), metoprolol (2.3) [12], and esmolol (42.5) [13], and is at least about six times greater than other beta blockers.

Some recent prospective studies found that low-dose landiolol administration during cardiac surgery prevented POAF. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the effectiveness and safety of landiolol administration for the prevention of POAF in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration [14] and the PRISMA group for reporting meta-analyses [15]. The analysis in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Sources and Search

The Medline/PubMed and BioMed Central databases were searched for reports of randomized trials that were published before December 1, 2013, in English. Searches were restricted to human clinical studies that were conducted as randomized controlled trials. The search terms used were “landiolol”, “prevention”, “postoperative atrial fibrillation”, “cardiac surgery”, and “randomized”.

Study Selection

Two independent reviewers selected the studies for inclusion, with any differences resolved by consensus. The reviewers first checked the titles and abstracts of the studies and then reviewed the full papers to obtain additional information. All reports of randomized controlled trials that compared patients who received landiolol with a control group who received saline, no treatment, or other treatment were considered. The POAF criteria had to be defined in the report, and only patients who were observed for POAF over at least 3 days were considered suitable for analysis.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The reviewers extracted the following data: patient characteristics, start of landiolol administration, duration of landiolol administration, type of surgery, definition of atrial fibrillation, landiolol dose, and incidence of POAF. Study validity was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool [16].

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The raw event rates of POAF were derived from the individual studies and 2 × 2 tables were constructed using the number of events and the total population of the trial. Analysis was based on the intention-to-treat principle. Binary outcomes of the individual studies were analyzed to compute individual and pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Heterogeneity was assessed and quantified with the I 2 statistic computed using the Cochran Q test. An I 2 value of <25% is considered good consistency, 25–50% is acceptable, and more than 50% is unacceptable. Pooled effect estimates among studies were analyzed using the Mantel–Haenszel method (fixed effects model) as every study yielded an identical result and the I 2 value was <50%.

To assess publication bias and other types of bias, funnel plots for log OR were created, where the log ORs were plotted against their standard errors. The symmetry of the funnel plots was tested using the Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test [17].

To assess the robustness of the conclusions of the analyses, one study was removed at a time to asses each study’s impact on the results. Furthermore, the data were analyzed in four groups: all randomized controlled studies, all coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) studies, CABG studies with control groups that received saline or nothing, and all cardiac surgery studies with control groups that received saline or nothing.

Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager, version 5.2 (RevMan; The Cochrane Collaboration 2013, The Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark) or SAS for Windows version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Search Results

The literature search returned six trials that evaluated the pharmacological prevention of POAF by landiolol administration published before December 1, 2013 (Table 1) [18–23]. These were all randomized controlled trials that compared landiolol administration with a control group, defined the POAF criteria used, and observed patients for POAF for more than 3 days, 7 days in five trials and 3 days in one trial. Therefore, all six studies were included in the final analysis.

Table 1.

Randomized controlled trials included in this meta-analysis, showing the number of patients, time of start of drug administration, and mean duration of drug administration

| Journal | Year | Patients, n | Start of drug administration | Mean duration of drug administration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landiolol | Control | ||||

| J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg [18] | 2011 | 70 | 70 | At the time of central anastomosis | 48 h |

| J Thorc Cardiovasc Surg [19] | 2012 | 77 | 34 | At the completion of central anastomosis | 72 h |

| J Cardiovasc Surg [20] | 2012 | 36 | 34 | In the ICU immediately after surgery | Until resumption of oral intake (50 h) |

| Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann [21] | 2013 | 68 | 68 | Immediately after induction of anesthesia | 48 h |

| Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg [22] | 2013 | 21 | 22 | At the start of ICU admission | Until resumption of oral intake (1.6 days) |

| Int Heart J [23] | 2012 | 30 | 30 | At the start of ICU admission | 72 h |

ICU intensive care unit

Study Characteristics

A total of 560 patients were randomly divided into two groups (302 to the landiolol group and 258 to the control group). All patients were Japanese. The number of patients enrolled in each study ranged from 43 to 140 (Table 1). Five studies included only patients who underwent CABG, and one study also included patients who underwent valvular surgery (Table 2). In the CABG studies, most patients were males. Most of the studies excluded patients with a history of arrhythmia, severe cardiac dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction <20%, <30%, or <40%), sinus bradycardia (resting heart rate <50 beats/min or <60 beats/min), and second- or third-degree atrioventricular block. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction before landiolol administration was within the normal range in all studies (range 54.1–64.0%). Heart rate were decreased about ten beats/min compared with control groups in four studies [18–20, 23], but it is not different in study compared with diltiazem [22]. Blood pressure is not different compared with control or diltiazem groups in five studies [18–20, 22, 23]. In one study [21], the values of heart rate and blood pressure were not described.

Table 2.

Details of the studies, types of surgery, characteristics of the treatment and control groups, and definitions of atrial fibrillation

| References | Groups | Surgery | Treatment group | Control group | Definition of atrial fibrillation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sezai et al. [18] | 2 | On-pump CABG | Landiolol | Placebo | ≥5 min or a requirement for treatment because of hemodynamic changes |

| Sezai et al. [19] | 3 | On-pump CABG | Landiolol | Placebo | ≥5 min or a requirement for treatment because of hemodynamic changes |

| Landiolol and oral bisoprolol | ≥5 min or a requirement for treatment because of hemodynamic changes | ||||

| Fujii et al. [20] | 2 | Off-pump CABG | Landiolol and oral carvedilol after extubation | No treatment and oral carvedilol after extubation | Irregular narrow-complex rhythm with absence of a discrete P wave lasting >10 min, or a requirement for treatment because of intolerable symptoms or hemodynamic deterioration |

| Ogawa et al. [21] | 2 | Off-pump CABG | Landiolol | No treatment | ≥10 min |

| Nagaoka et al. [22] | 2 | Off-pump CABG | Landiolol | Diltiazem | New-onset atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter requiring treatment or lasting >5 min |

| Sakaguchi et al. [23] | 2 | Valve replacement/valvuloplasty | Landiolol | No treatment | ≥1 min |

CABG coronary artery bypass grafting

Landiolol administration was started immediately after the induction of anesthesia, from the time of central anastomosis during surgery, or from the time of admission to the ICU. Landiolol was administered by continuous intravenous infusion at a dose of 0.5–10 µg/kg/min for 48–72 h (Table 1). Patients received a standard dose in two studies, and in the other studies they received a titrated dose to maintain a low heart rate (Table 3). Patients in the control groups received a placebo (saline) in two studies, diltiazem in one study, and no treatment in three studies. One study administered oral carvedilol after the end of landiolol administration (Tables 2, 3).

Table 3.

Drug doses

| References | Groups | Landiolol dose | Control drug dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sezai et al. [18] | 2 | 2 µg/kg/min ci | Saline |

| Sezai et al. [19] | 3 | 5 µg/kg/min ci initially | Saline |

| 5 µg/kg/min ci and oral or nasogastric administration of bisoprolol (2.5 mg/day) from the day after surgery | |||

| Fujii et al. [20] | 2 | 6.3 µg/kg/min ci (mean value) followed by oral carvedilol (2.5–5 mg/day) | Oral carvedilol (2.5–5 mg/day) after extubation and resumption of oral intake |

| Ogawa et al. [21] | 2 | 3–5 µg/kg/min ci | No drug given |

| Nagaoka et al. [22] | 2 | 0.5–1 µg/kg/min ci | Diltiazem, 0.5–1 µg/kg/min ci |

| Sakaguchi et al. [23] | 2 | 10 µg/kg/min ci initially, titrated according to heart rate and blood pressure (2.5–10 µg/kg/min) | No drug given |

ci continuous infusion

All six studies had a single-center design with a small patient population. Only two had a double-blind study design, and the other four were open randomized studies. The results of all studies were published as full articles.

The assessment of study quality is shown in Table 4. Five studies described the method of randomization, of which four used concealed randomization. The overall risk of bias was low in all studies.

Table 4.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies

| References | Adequate sequence generation | Allocation concealment used | Blinding | Concurrent therapies similar | Incomplete outcome data addressed | Uniform and explicit outcome definitions | Free of selective outcome reporting | Free of other bias | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sezai et al. [18] | Yes (lottery method) | Yes (double-blind) | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Sezai et al. [19] | Yes (lottery method) | Yes (double-blind) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Fujii et al. [20] | Yes (computer-generated randomization table) | Yes (computed) | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Low |

| Ogawa et al. [21] | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Low |

| Nagaoka et al. [22] | Yes (computer-generated table) | Yes (computed) | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Low |

| Sakaguchi et al. [23] | Yes (coin toss method) | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Low |

Quantitative Data Synthesis

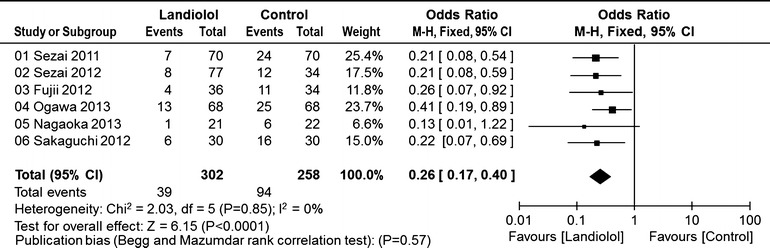

In all six randomized controlled studies, the incidence of POAF was significantly lower in patients who received landiolol than in the control group (39/302, 12.9% vs. 94/258, 36.4%; OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.17–0.40; P for effect <0.0001; P for heterogeneity = 0.85; I 2 = 0%; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pooled estimates of the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation in all randomized controlled studies

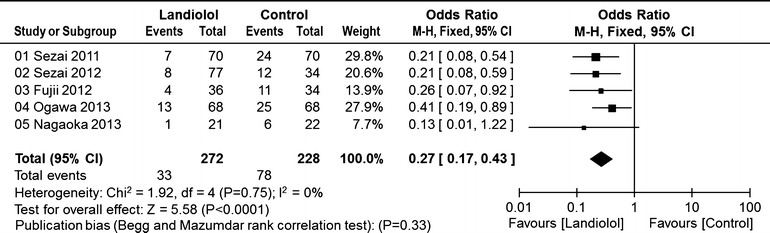

In the five CABG studies, the incidence of POAF was significantly lower in the landiolol group than in the control group (33/272, 12.1% vs. 78/228, 34.2%; OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.17–0.43; P for effect <0.0001; P for heterogeneity = 0.75; I 2 = 0%; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pooled estimates of the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation in randomized controlled studies of coronary artery bypass graft surgery

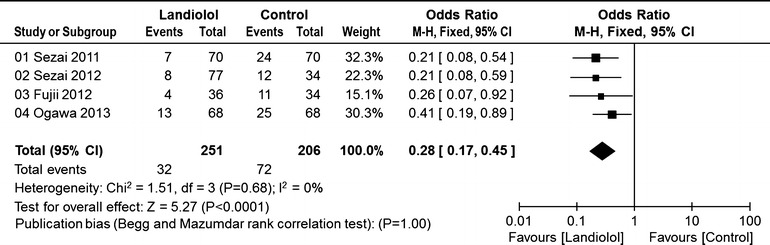

In the four CABG studies that compared a landiolol group with a control group that received saline or nothing, the incidence of POAF was significantly lower in the landiolol group than in the control group (32/251, 12.7% vs. 72/206, 34.9%; OR 0.28; 95% CI 0.17–0.45; P for effect <0.0001; P for heterogeneity = 0.68; I 2 = 0%; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pooled estimates of the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation in randomized controlled studies of coronary artery bypass graft surgery in which the control group received saline or nothing

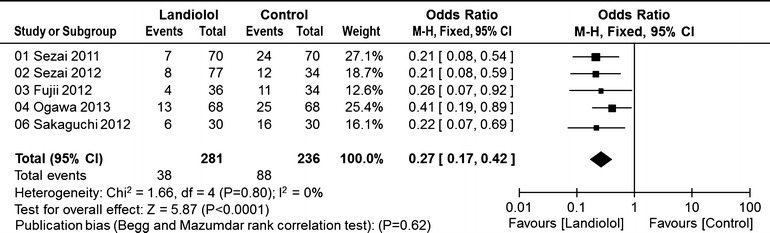

In the five cardiac surgery studies that compared a landiolol group with a control group that received saline or nothing, the incidence of POAF was significantly lower in the landiolol group than in the control group (38/281, 13.5% vs. 88/236, 37.2%; OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.17–0.42; P for effect <0.0001; P for heterogeneity = 0.80; I 2 = 0%; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Pooled estimates of the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation in randomized controlled studies of cardiac surgery in which the control group received saline or nothing

Safety analysis found that only two patients developed adverse events (2/302, 0.7%), including one case of hypotension and one case of exacerbation of asthma. Landiolol administration was immediately stopped in these patients, and they subsequently recovered.

Discussion

Beta-blockers are widely used during the perioperative period in cardiac surgery patients, but the clinical usefulness of intravenous beta-blocker administration remains unclear [2–6]. This meta-analysis found that landiolol administration significantly reduced the incidence of POAF following cardiac surgery. The effectiveness of landiolol administration was similar for both CABG and valvular surgery, indicating that this treatment is effective and safe in patients undergoing major cardiac surgery.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to clearly determine the effects of landiolol administration on other factors such as cerebral infarction, duration of ICU stay and hospitalization, and hospital cost, because analysis of these factors differed among studies. However, the PASCAL trial (UMIN-CTR Clinical Trial #UMIN000001442) [18], which was performed in double-blinded manner, revealed not only reduction of POAF but also reduction of the length of hospital stay. In addition, the anti-inflammation effects of landiolol were described in three trials [18, 19, 21]. Moreover, the impact of perioperative landiolol administration on prognosis is not clear. These issues should be further evaluated in a multicenter randomized controlled trial.

Beta-blockers provide credible protection against cardiovascular events and mortality in cardiac surgery patients. The ACCF/ACC guideline recommends that beta-blockers should be administered for at least 24 h before CABG in all patients without contraindications, should be reinstituted as soon as possible after CABG, and should be prescribed to all CABG patients at the time of hospital discharge [2]. The findings of this meta-analysis suggest that landiolol administration prevents POAF after cardiac surgery, but do not give a clear indication of the optimal time to start administration. At present, it seems beneficial to use an oral agent from 24 h before surgery, administer intravenous landiolol during surgery and after surgery until oral administration can be resumed, and then continue oral administration of beta-blockers, as indicated in the guideline. Further evidence will be needed to clarify the optimal time and dose of beta-blocker administration.

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that landiolol administration is effective and safe for the prevention of POAF. However, the treatment effect for conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm in cardiac surgery patients is not clear. The only randomized controlled trial evaluating the use of landiolol for the treatment of POAF found that landiolol administration resulted in earlier conversion to sinus rhythm than diltiazem administration and that landiolol was more effective for controlling the heart rate than diltiazem [24]. Adverse events, such as bradycardia and hypotension, are less common with landiolol than with diltiazem. The treatment effect of landiolol should therefore be studied further.

Limitations

This meta-analysis is limited by the lack of availability of all relevant data. Most studies did not include stroke rate, lengths of ICU and hospital stay, or treatment costs as end-points. Only two studies were performed in a blinded manner, and the remaining studies were open randomized controlled trials. All the studies were conducted at a single center. Only a few clinical studies were suitable for inclusion, and a further meta-analysis that includes more than ten trials would be useful.

Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that landiolol administration during surgery or immediately after ICU admission is effective for the prevention of POAF after cardiac surgery. Additional large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled parallel trials are necessary to confirm these positive results.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article or payment of the article processing charges. All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Atsuhiro Sakamoto received speaker’s fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Masafumi Kitakaze received speaker’s fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Toshimitsu Hamasaki declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The analysis in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College Of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2009;120:e169–e276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:e652–e735. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823c074e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell LB, CCS Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Committee Canadian Cardiovascular Society atrial fibrillation guidelines 2010: prevention and treatment of atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, et al. Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS); European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2501–2555. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Chami M, Kilgo FP, Thourani V, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation predicts long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass graft. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1370–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalavrouziotis D, Buth KJ, Ali IS. The impact of new-onset atrial fibrillation on in-hospital mortality following cardiac surgery. Chest. 2007;131:833–839. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plosker GL. Landiolol: a review of its use in intraoperative and postoperative tachyarrhythmias. Drugs. 2013;73:959–977. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iguchi S, Iwamura H, Nishizaki M, et al. Development of a highly cardioselective ultra short-acting beta-blocker, ONO-1101. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1992;40:1462–1469. doi: 10.1248/cpb.40.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugiyama A, Takahara A, Hashimoto K. Electrophysiologic, cardiohemodynamic and beta-blocking actions of a new ultra-short-acting beta blocker, ONO-1101, assessed by the in vivo canine model in comparison with esmolol. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34:70–77. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasao J, Tarver SD, Kindscher JD, Taneyama C, Benson KT, Goto H. In rabbits, landiolol, a new ultra-short-acting b-blocker, exerts a more potent negative chronotropic effect and less effect on blood pressure than esmolol. Can J Anesth. 2001;48:985–989. doi: 10.1007/BF03016588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshiya I, Ogawa R, Okumura F, et al. Clinical evaluation of landiolol hydrochloride (ONO-1101) on perioperative supraventricular tachyarrhythmia—a phase III, double-blind study in comparison with placebo [in Japanese] Rinsho Iyaku (J Clin Ther Med) 1997;13:4949–4978. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker JG. The selectivity of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists at the human beta1, beta 2 and beta 3 adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:317–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murao K, Yamada M, Yamada K, et al. An antagonistic effect of esmolol on beta-3 adrenoceptor in brown adipose tissue in rats. J Anesth. 2002;16:265–267. doi: 10.1007/s005400200039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (last accessed April 3, 2014).

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. http://ohg.cochrane.org/sites/ohg.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Risk%20of%20bias%20assessment%20tool.pdf (last accessed April 3, 2014).

- 17.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sezai A, Minami K, Nakai T, et al. Landiolol hydrochloride for prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting: new evidence from the PASCAL trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1478–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sezai A, Nakai T, Hata M, et al. Feasibility of landiolol and bisoprolol for prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting: a pilot study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujii M, Bessho R, Ochi M, et al. Effect of postoperative landiolol administration for atrial fibrillation after off pump coronary artery bypass surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2012;53:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogawa S, Okawa Y, Goto Y, et al. Perioperative use of a beta blocker in coronary artery bypass grafting. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2013;21:265–269. doi: 10.1177/0218492312451166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagaoka E, Arai H, Tamura K, Makita S, Miyagi N. Prevention of atrial fibrillation with ultra-low dose landiolol after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013. doi:10.5761/atcs.oa.12.02003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Sakaguchi M, Sasaki Y, Hirai H, et al. Efficacy of landiolol hydrochloride for prevention of atrial fibrillation after heart valve surgery. Int Heart J. 2012;53:359–363. doi: 10.1536/ihj.53.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakamoto A, Kitakaze M, Takamoto S, et al. Landiolol, an ultra-short-acting β1-blocker, more effectively terminates atrial fibrillation than diltiazem after open heart surgery: prospective, multicenter, randomized, open-label study (JL-KNIGHT study) Circ J. 2012;76:1097–1101. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.