Abstract

Objective

To assess the rate and type of maternal and infant complications among pregnant women receiving low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH).

Study Design

Retrospective study of pregnant women on LMWH referred to two university hematology clinics from January 2001 to December 2010. We recorded the number of pregnancies, indication, dose and dose adjustments for LMWH, pregnancy outcomes (live births, maternal and infant complications) and side effects of LMWH.

Results

There were 89 pregnancies in 76 women. The most common indication for LMWH was a history of adverse outcome of pregnancy associated with thrombophilia. LMWH was adjusted in 75% and 45% of pregnancies in women on therapeutic and prophylactic doses, respectively. Live birth rate was 97%. There were 25 maternal and 11 infant complications. Side effects were minimal and included decreased bone mineral density and bleeding.

Conclusion

LMWH use among pregnant women is associated with successful pregnancy outcomes. While side effects were minimal, maternal and infant complications occurred in 28% and 12% of cases, respectively.

Keywords: low-molecular weight heparin, pregnancy, anticoagulation, outcomes, pregnancy

Introduction

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) have largely replaced unfractionated heparin (UFH) for the prophylaxis and management of venous thromboembolism (VTE). The advantages of LMWH over UFH include an enhanced anti-Xa to anti-IIa ratio resulting in a more stable and predictable dose-response curve with no routine monitoring, and reduced risk of bleeding, osteoporosis and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) (1). In the context of pregnancy, LMWH is used for prophylaxis and treatment of VTE and may be used for prevention of systemic embolism in women with mechanical heart valves (2, 3). LMWH is also administered for VTE prophylaxis in women with high-risk hereditary thrombophilia (4) and has been prescribed in women with previous history of adverse outcomes of pregnancy (AOP) (5, 6).

Published guidelines recommend the use of LMWH for prophylaxis and treatment of VTE in pregnancy (4, 5). However, although widely used in pregnancy (7), LMWH remain an off- label indication. The type of LMWH used, dosing regimens, and target anti-Xa levels and frequency of anti-Xa monitoring are highly variable in the pregnant population and have been derived from pilot, observational studies and empirical evidence (1, 8). Additionally, the use of LMWH for prevention of recurrent pregnancy losses remains controversial in women with inherited and acquired thrombophilia (9, 10, 11, 12). Nevertheless, several studies have confirmed the safety of LMWH therapy during pregnancy and the low risk of potential maternal and infant side effects (7, 13). The purpose of our study was to evaluate the maternal and infant complications and side effects associated with the use of LMWH in pregnancy.

Methods

Study population and data collection

We retrospectively evaluated the electronic medical records of 89 pregnancies in 76 women who were referred to our hematology clinic for LMWH anticoagulation monitoring during pregnancy at two university medical centers (Mount Sinai Medical Center and New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical Center) from January 2001 to December of 2010. Data collected included: age, type of pregnancy defined as natural or with assisted reproductive technique (ART), indications and dosing regimen for LMWH (prophylactic or therapeutic) and post-partum thromboprophylaxis. Peripartum management of anticoagulation, type of anesthesia used and mode of delivery were recorded.

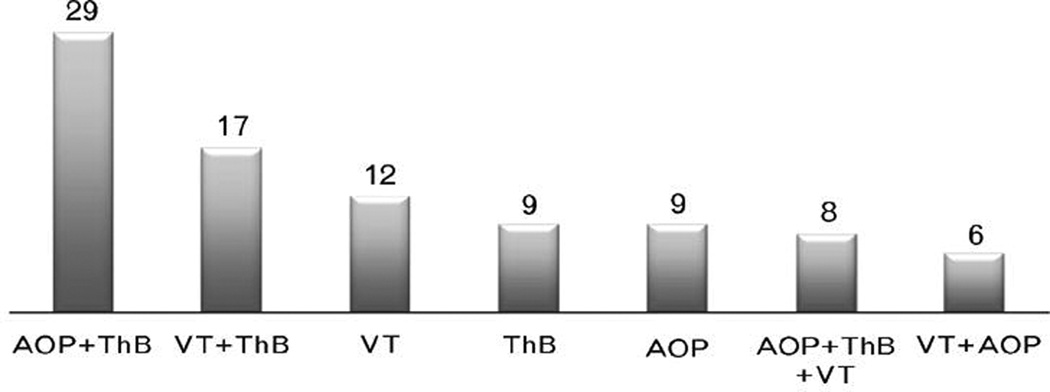

Anticoagulation was used for a variety of indications including a new diagnosis or history of vascular thrombosis (VT) (arterial and/or venous), inherited or acquired thrombophilia, a history of adverse outcomes of pregnancy (AOP), or a combination of the above indications (Figure 1). Vascular thrombosis (VT) was classified as venous: deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) and/or pulmonary embolism (PE) or as arterial thrombosis: stroke. Thrombophilia was classified as either inherited or acquired. Inherited thrombophilia included deficiencies in antithrombin (AT), protein C and S, and Factor V Leiden, and prothrombin gene G20210A mutations. Acquired thrombophilia was characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies defined as anti-cardiolipin antibodies (IgG >20 GPL and/or IgM >20 MPL) and/or anti-Beta 2 glycoprotein 1 IgG or IgM above the 90th percentile and/or positive lupus anticoagulant (LAC) in two different occasions at least 12 weeks apart (14). Previous history of AOP included recurrent unexplained pregnancy losses, preeclampsia, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, placental abruption, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and stillbirth.

Figure 1.

Adverse Outcomes of Pregnancy and Thrombophilia (AOP + ThB); Vascular Thrombosis and Thrombophilia (VT + ThB); Vascular Thrombosis (Arterial and/or Venous)(VT); History of Adverse Outcomes of Pregnancy (AOP); Thrombophilia (ThB); Vascular Thrombosis, Thrombophilia and History of Adverse Outcomes of Pregnancy (VT + ThB + AOP); Vascular Thrombosis and History of Adverse Outcomes of Pregnancy (VT+ AOP

The dosing regimen was classified as prophylactic (40 mg subcutaneously (SC) once daily for enoxaparin or 5000 IU SC for dalteparin) or therapeutic (1 mg/kg SC every 12 hours for enoxaparin). Therapeutic LMWH was administered in women who were on chronic anticoagulation prior to the pregnancy for primary thromboprophylaxis of arterial embolism or for secondary thromboprophylaxis of venous thromboembolism.

Anti-Xa activity was measured 4 hours after LMWH administration. The anti-Xa activity range in both institutions is between 0.6–1.1 IU/ml and between 0.2–0.5 IU/ml for the therapeutic and prophylactic dose, respectively using the appropriate calibrator. Dose adjustments of LMWH were performed when the anti-Xa activity was outside the reference range.

The primary outcome measures were the frequency of maternal and infant complications. Maternal complications included anemia, hypertension, pre-eclampsia, bleeding, pre-term labor and venous thromboembolism. Infant complications included intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), congenital defects, and seizures Side effects of LMWH examined were bleeding, allergic reactions, thrombocytopenia, and decreased bone mineral density among those women who underwent bone mineral densitometry testing.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (including mean, standard deviation, median, range, frequency, percent) were calculated to characterize the study cohort. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used, as appropriate, to evaluate the association between type of dosing regimen (i.e., treatment vs. prophylactic dose) and 1) maternal complications, 2) infant complications, 3) dosing adjustment, 4) type of pregnancy (natural/ART), and 5) adverse pregnancy outcomes. All p-values are two-sided with statistical significance evaluated at the 0.05 alpha level. All analyses were performed in SPSS Version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

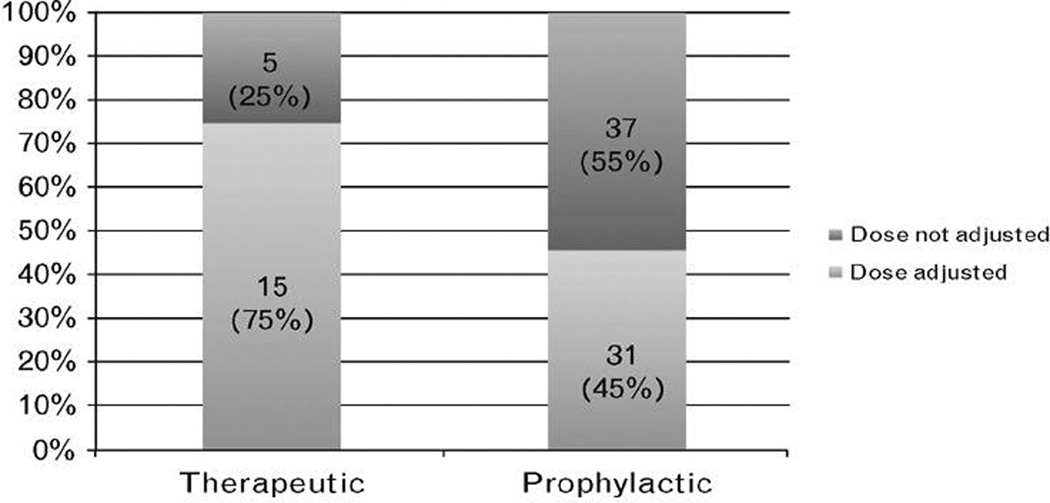

A total of 89 pregnancies in 76 women were analyzed. The mean age was 35 years and one third of the pregnancies were achieved with assisted reproductive techniques (ART) (Table 1). Indications for the use of LMWH are shown in Figure 1. The main indication for the use of LMWH was a previous history of AOP with an identified thrombophilia. LMWH dose adjustments are shown in Figure 2. Nearly three quarters of the pregnancies in women who received treatment dose LMWH and half of pregnancies in those who received prophylactic dose required dose increments during the course of pregnancy. Women who received prophylactic dose LMWH were less likely to have their dose adjusted compared to women on the therapeutic dose (44.9% vs. 75.0%, respectively, P=0.02).

Table 1.

| Number of women | 76 |

| Number of pregnancies | 89 |

| Mean age (year, range) | 35 (23–48) |

| Type pregnanciesa | |

| Natural (%) | 64 (72%) |

| Assisted reproductive techniques (%) | 22 (25%) |

There was no information on the type of pregnancies in three cases.

Figure 2.

Dose adjustment for LMWH was required in 75% and 45% of pregnant women on therapeutic and prophylactic doses, respectively.

LMWH was replaced by UFH in the third trimester (at approximately 36 weeks of gestation) in more than half of the pregnancies (Table 2). LMWH was switched to UFH (5000 units SC every 12 hours) in 59% of pregnancies in women receiving the prophylactic dose and in 58% of pregnancies in women receiving the therapeutic dose, respectively, P= 0.99). The therapeutic UFH dose was calculated as 250 IU/kg SC every 12 hours or continuous infusion of 18 IU/kg/h. Therapeutic SC UFH was stopped 24 hours prior to delivery while IV UFH was discontinued 4 hours prior to labor induction.

Table 2.

| Pregnancies in which LMWH was switched to UFH in the third trimester | 47 (52) | |

| Type of anesthesiaa | General anesthesia | 3 |

| Regional anesthesia | 66 | |

| Type of delivery (%)b | Spontaneous vaginal delivery (%) | 21 (23) |

| Unplanned C-section (%) | 8 (9) | |

| Induced vaginal delivery (%) | 25 (28) | |

| Planned C-section (%) | (29) |

LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin, UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Information was not available regarding type of anesthesia in 21 pregnancies.

Information was not available regarding method of delivery in nine pregnancies.

There were 5 pregnancies in 4 patients with hereditary antithrombin (AT) deficiency; in all these pregnancies AT replacement was administered at the time of delivery. One pregnant woman with hereditary AT deficiency received recombinant human AT (AT alfa-ATryn) as part of a clinical trial, another with hereditary AT deficiency received ATIII-DAF/DI (a plasma derived AT) also on a clinical trial and the other 3 pregnancies in 2 patients with hereditary AT deficiency were managed with plasma derived AT (Thrombate) at the time of delivery.

Peri-partum management of anticoagulation, anesthesia (regional versus general) used and modes of delivery (vaginal versus cesarean section [C-section]) are shown in Table 2. Post-partum thromboprophylaxis was administered in 83% of the women. Regional anesthesia was used in 73% of the pregnancies. Induced delivery occurred in 57% (Table 2).

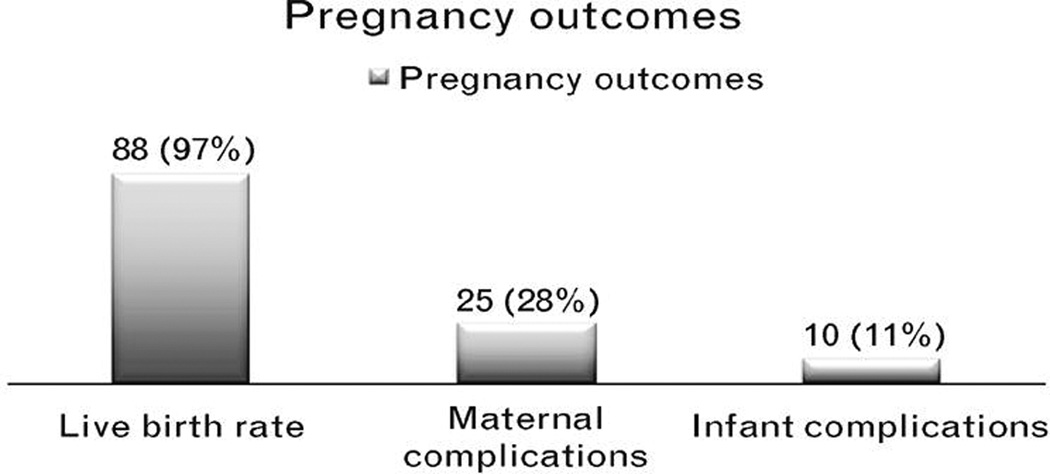

There were 25 maternal and 11 infant complications (Figure 3). Women who had maternal complications were on average 3 years older than women without complications (37 vs. 34.5 yr, p=0.02). Maternal complications were identical for women receiving therapeutic and prophylactic dose LMWH (30.0% vs. 29.9%, respectively, P=0.99). Two women on post-partum thromboprophylaxis developed pulmonary embolism (one within 72 hours after a C- section and another approximately 8 weeks after C-section). Infant complications tended to be more prevalent among women receiving therapeutic compared to prophylactic dose (21.1% vs. 9.1%, respectively, P=0.15; trend indicated). Infant complications were similar regardless whether the pregnancy was achieved naturally or with ART (14.3%vs. 11.1%, respectively; P=0.70). The 21 pregnancies with ART comprised 17 IVF and 4IUI pregnancies. Maternal age did not affect the incidence of infant complications.

Figure 3.

The most common maternal complication was hypertension and the most common infant complication was intrauterine growth restriction. There was one death due to umbilical cord accident.

The most common side effect was decreased bone mineral density (BMD) in 8 women, followed by bleeding (n=6), and thrombocytopenia (n=1). Decreased BMD was less prevalent among women receiving therapeutic dose than prophylactic dose (16.7% vs. 33.3% respectively, P=0.63). However, this analysis is underpowered as there were no BMD examinations performed in 63 pregnancies and there were no pre-pregnancy BMD examinations performed for comparison. None of the bleeding complications were major. However there was 1 woman with a clinically significant vaginal bleeding (due to subchorionic hematoma) in the first trimester that required temporary interruption of prophylactic LMWH. One woman developed mild thrombocytopenia.

Discussion

Our study among pregnant women with a broad variety of indications for LMWH anticoagulation demonstrated a high live birth rate. While side effects were minimal, there were several maternal and infant complications associated with the use of LMWH. We also found that dose adjustments were required in 75% of pregnant women on therapeutic LMWH, and in 45% of women on prophylactic dose during the second and third trimester of pregnancy.

The most common maternal and infant complications were hypertension and intrauterine growth restriction, respectively. Of note, there was no relationship between the dose of LMWH and the occurrence of maternal complications. However, there was a trend towards a greater number of infant complications in the pregnancies managed with therapeutic dose LMWH. We were not able to identify any variable that could account for this finding. On the other hand, in contrast to what is described in the literature, we did not find any relationship between the type of pregnancy (ART or natural) and the rate of infant complications. (18

There were very few side effects related to the use of LMWH with decreased bone mineral density (BMD) being the most prevalent. However, our study was underpowered to analyze for decreased BMD as the majority of our pregnant women did not have BMD examinations. A recent study suggested that the use of long-term prophylactic LMWH in pregnancy was not associated with a significant decrease in BMD [19]; however it remains unclear whether therapeutic dose of LMWH is a risk factor for osteoporosis. In our hematology practice we routinely advise our pregnant women on LMWH to take calcium and vitamin D3 to minimize this side effect.

In approximately half of pregnancies, LMWH was switched to UFH in the third trimester of pregnancy mainly because of concern for potential spinal hematoma during regional anesthesia. (15) Regional anesthesia was administered in more than two-thirds of the deliveries and there were no complications recorded. In a recent study, 61% of women who had a singleton birth in a vaginal delivery received epidural or spinal anesthesia (16). About one third of the pregnancies were delivered via cesarean section, which is in concordance with the rate of cesarean sections performed in the United States (17).

Our study has several strengths. In contrast to published studies we evaluated a population of pregnant women who received LMWH for a variety of clinical indications ranging from thrombophilia, history of vascular thrombosis, to previous AOP or combinations of these disorders. We believe our study is more representative of “real world” practice at a tertiary care hematology setting. This is illustrated by the 5 pregnancies in 4 women with hereditary AT deficiency all of whom received AT replacement at the time of delivery, another patient with two mechanical heart valves (mitral and aortic), and a 44-year old woman with a myeloproliferative neoplasm who is homozygote for the JAK2V617F.

Recent national society guidelines recommend monitoring of anti-Xa activity in pregnant women managed with therapeutic dose of LMWH (4). In our study, dose adjustments occurred more frequently (75%) with therapeutic doses of LMWH and in 45% of pregnancies on prophylactic LMWH. These findings suggest that monitoring anti-Xa activity (targeting anti-Xa level between 0.2–0.5 IU/ml) may also be required even with prophylactic use of LMWH during pregnancy. This may be related to the known increase in glomerular filtration rate and rate of elimination of LMWH that occurs as the pregnancy progresses (20). Roeters van Lennep et al recently reported that although prophylaxis with LMWH during pregnancy and post-partum was safe, the risk of pregnancy-related VTE was considerable in women at high risk for VTE. The authors suggested that prophylactic dose of LMWH may not be sufficient for these pregnant women (21). Indeed, two women in our study developed post-partum venous thrombosis while receiving prophylactic doses of LMWH.

Our study has important limitations including its retrospective design, the relatively small sample size, and performance in a single hematology clinic practice. It is important to note that our pregnant women were very closely followed in our hematology clinics with the majority of them monitored on a monthly basis. Close communication with the referring obstetrician was maintained during the antepartum and peripartum period. Finally, the average age of 35 years of our pregnant women is 10 years older than the average age (25 years) of pregnant women in the US (22), reflecting a referral bias of our study population.

In conclusion, LMWH use among pregnant women with various indications for anticoagulation was associated with successful pregnancy outcomes in the vast majority of cases. While side effects were minimal, maternal and fetal complications occurred in 28% and 12% of cases, respectively. Our findings suggest that monitoring for anti-Xa activity needs to be considered when using prophylactic dose of LMWH in pregnancy, as almost half of our pregnant women receiving prophylaxis required dose adjustments. Further multicenter prospective studies and international registries of pregnant women on LMWH are necessary to broaden our knowledge in optimizing the care of women who require anticoagulation during pregnancy.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Paul Christos was partially supported by the following grant: Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC) (UL1-RR024996).

We thank Dr. Babette Weksler and Dr. Stephen M. Pastores for their valuable suggestions to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Support: None

Disclaimer: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Patel JP, Hunt BJ. Where do we go now with low molecular weight heparin use inobstetric care? J ThrombHaemost. 2008;6(9):1461–1467. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLintock C. Anticoagulant therapy in pregnant women with mechanical prostheticheart valves: No easy option. Thromb Res. 2011;127(Suppl 3):S56–S60. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(11)70016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yinon Y, Siu SC, Warshafsky C, Maxwell C, McLeod A, Colman JM, et al. Use of low molecular weight heparin in pregnant women with mechanical heart valves. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(9):1259–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates SM, Greer IA, Pabinger I, Sofaer S, Hirsh J American College of Chest Physicians. Venous thromboembolism, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition) Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):844S–886S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greer IA, Nelson-Piercy C. Low-molecular-weight heparins for thromboprophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy: A systematic review of safety and efficacy. Blood. 2005;106(2):401–407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rey E, Garneau P, David M, Gauthier R, Leduc L, Michon N, et al. Dalteparin for the prevention of recurrence of placental-mediated complications of pregnancy in women without thrombophilia: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(1):58–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deruelle P, Coulon C. The use of low-molecular-weight heparins in pregnancy—howsafe are they? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19(6):573–577. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282f10e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedrich E, Hameed AB. Fluctuations in anti-factor Xa levels with therapeutic enoxaparin anticoagulation in pregnancy. J Perinatol. 2010;30(4):253–257. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark P, Walker ID, Langhorne P, Crichton L, Thomson A, Greaves M, et al. Scottish Pregnancy Intervention Study (SPIN) collaborators. SPIN (Scottish Pregnancy Intervention) study: A multicenter, randomized controlled trial of low molecular-weight heparin and low-dose aspirin in women with recurrent miscarriage. Blood. 2010;115(21):4162–4167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-267252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaandorp SP, Goddijn M, van der Post JA, Hutten BA, Verhoeve HR, Hamulyak K, et al. Aspirin plus heparin or aspirin alone in women with recurrent miscarriage. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1586–1596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laskin CA, Spitzer KA, Clark CA, Crowther MR, Ginsberg JS, Hawker GA, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and aspirin for recurrent pregnancy loss: Results from the randomized, controlled HepASA trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(2):279–287. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080763). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visser J, Ulander VM, Helmerhorst FM, Lampinen K, Morin-Papunen L, Bloemenkamp KW, et al. Thromboprophylaxis for recurrent miscarriage in women with or without thrombophilia. HABENOX: A randomised multicentre trial. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(2):295–301. doi: 10.1160/TH10-05-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoro R, Iannaccaro P, Prejano S, Muleo G. Efficacy and safety of the long-termadministration of low-molecular-weight heparins in pregnancy. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2009;20(4):240–243. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e3283299c02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) . J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(2):295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Rowlingson JC, Enneking FK, Kopp SL, Benzon HT, et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine evidence-based guidelines (third edition) Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(1):64–101. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181c15c70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osterman MJ, Martin JA. Epidural and spinal anesthesia use during labor: 27-statereporting area, 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;59(5) 1,13, 16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macdorman M, Declercq E, Menacker F. Recent trends and patterns in cesarean and vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) deliveries in the United States. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38(2):179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fortunato A, Tosti E. The impact of in vitro fertilization on health of the children: Anupdate. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;154(2):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Templier G, Rodger MA. Heparin-induced osteoporosis and pregnancy. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14(5):403–407. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283061191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thornburg KL, Jacobson SL, Giraud GD, Morton MJ. Hemodynamic changes inpregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24(1):11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(00)80047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roeters van Lennep JE, Meijer E, Klumper FJ, Middeldorp JM, Bloemenkamp KW, Middeldorp S. Prophylaxis with low-dose low-molecular-weight heparin during pregnancy and postpartum: Is it effective? J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(3):473–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Delayed childbearing: More women are having their first child later in life. NCHS data brief, no 21. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. Aug, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]