Abstract

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) is a relatively rare tumor, but is characterized by high rates of recurrence, morbidity, and mortality. Choice of treatment modality is generally influenced by lesion size, grade, and focality. Radical nephroureterectomy with bladder cuff excision is the gold-standard management of UTUC, although an organ-sparing approach may be beneficial in selected patients. Conservative endoscopic management of UTUC in appropriate patients has a favorable impact on quality of life and health care costs when compared with patients who progress to dialysis-dependent renal failure. Careful ureteroscopic surveillance following endoscopic management of UTUC is essential.

Key words: Upper tract urothelial carcinoma, Tumor grade, Nephron-sparing endoscopic treatment, Topical adjuvant chemo-immunotherapy, Oncologic outcomes

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) accounts for < 5% of all cases of urothelial neoplasia, but is a very morbid disease, with recurrence rates up to 90%1–9 and 5-year survival rates ranging from 30% to 60%.10 Radical nephroureterectomy (NU) with bladder-cuff excision has been the traditional treatment for UTUC because of its high rate of recurrence. However, given the morbidity of nephrectomy and the risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) or dialysis-dependent renal failure, as well as the risk of contralateral tumors,11–14 a nephron-sparing approach may be preferable in selected patients.

Diagnosis

Patients with UTUC commonly present with hematuria and occasionally report flank pain, and 10% to 15% have incidental lesions detected on radiographic evaluation. Upper tract imaging may include ultrasound, intravenous urography (IVU), retrograde ureteropyelography, or computed tomography (CT) scanning. IVU has poor sensitivity and specificity for detection of such tumors, and retrograde ureteropyelography has a 25% false-negative rate.15,16 CT scanning is 90% sensitive, but it understages invasive tumors in 59% of cases.17 Urine cytology examination is also unreliable in the diagnosis of UTUC, with low sensitivity and a specificity of 60%,17 although it is more accurate in detecting high-grade lesions.18,19

When UTUC is suspected, ureteroscopy provides the most valuable diagnostic information, allowing close visual inspection and biopsy. In their study of 40 tumors, El-Hakim and colleagues demonstrated that ureteroscopic appearance was only 70% accurate in determining the grade of UTUC lesions,20 whereas the specificity of ureteroscopic-guided biopsy for determining tumor grade ranges from 75% to 92%.17 Accurate assessment of tumor grade is important because of its significant association with recurrence rate, reported to be 100% in patients with high-grade tumors, and 60% in low-grade tumors.1

Staging

A potential problem with endoscopic biopsy of upper tract tumors is the lack of reliability in primary tumor staging. An accurate determination of depth of invasion is essential when considering conservative therapy. In bladder cancer, accurate staging is one of the goals of transurethral resection, with a proper resection of the bladder wall including muscularis propria. This is difficult to achieve in upper tract lesions because of the markedly diminished upper tract collecting system wall thickness, and the small size of ureteroscopically obtained biopsy specimens. Other currently available staging modalities, including CT scanning and endoluminal ultrasound, are also inaccurate in assessing depth of tumor penetration. Therefore, a combination of radiographic studies, ureteroscopic appearance, and biopsy tumor grade is necessary to provide the surgeon with the most accurate preoperative staging information. This is facilitated by a good correlation between the biopsy grade of the lesion and the tumor stage.2–4,20 Keeley and colleagues reported that, out of 30 low and low-moderate grade ureteroscopic specimens, 26 (87%) were found to be low-stage (Ta-T1) disease on final pathology.3

Patient Selection

Initial experience with nephronsparing surgery (NSS) for UTUC was limited to patients with imperative indications such as a solitary kidney, bilateral disease, significant perioperative risk, or severe renal insufficiency. Many authors continue to advocate endoscopic treatment only in imperative situations5–8,21,22 because of high 3-year recurrence rates. However, growing experience with NSS for non-imperative indications, coupled with improved technology and risk stratification, may result in widespread expansion of endoscopic treatment to patients with normal contralateral kidneys.1,9,23

Tumor grade, focality, size, and location should all be considered when selecting patients for NSS. Given the aforementioned difficulties in establishing depth of invasion, and the significant correlation between tumor grade and stage, tumor grade is a very important factor for predicting the aggressiveness of UTUC. Unifocal lesions < 1.5 cm in diameter can usually be treated ureteroscopically regardless of location.3 Multifocal disease and lesions > 1.5 cm are more likely to recur, however, possibly because of incomplete resection.3,24 Keeley and colleagues observed a strong correlation between tumor size and treatment success in 38 patients (41 renal units) treated ureteroscopically.3 Only 36% of renal units with tumors > 1.5 cm in diameter were rendered tumor free, compared with 91% of those with tumors < 1.5 cm in diameter. A retrospective study of 34 patients undergoing percutaneous resection reported a higher risk of recurrence for patients with multifocal tumors (62.5%) when compared with patients with unifocal tumors (38.5%).24 Van der Poel and colleagues reported a positive correlation between ureteral location and more aggressive behavior, observing a higher rate of invasion through the ureteral wall in proximal tumors than their distal counterparts, suggesting that proximal tumors may be less amenable to endoscopic treatment.10

Treatment

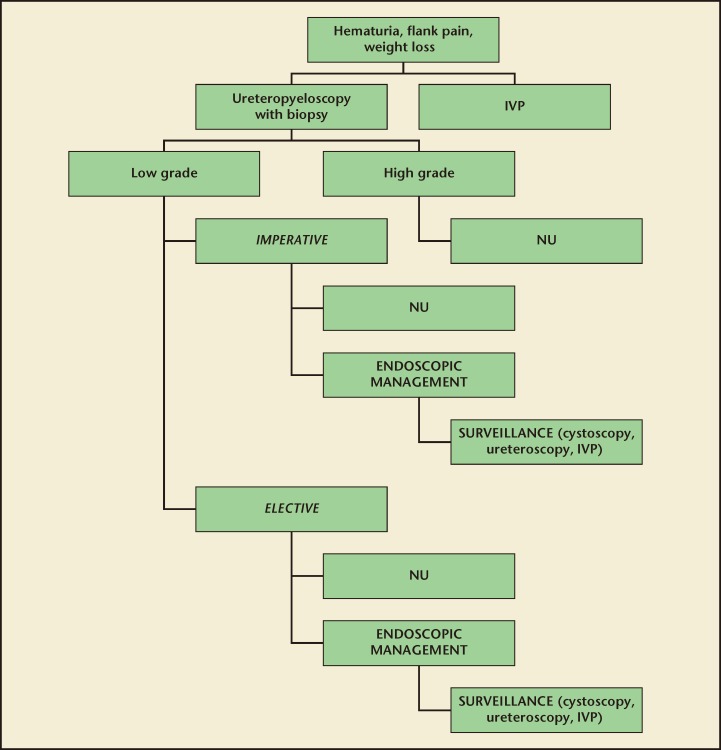

Of all UTUCs, approximately 75% are located in the collecting system of the kidney, and the remaining 25% occur in the ureter.25,26 Options for NSS depend on tumor location and size, and include partial nephrectomy, segmental ureterectomy, and endoscopic resection (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Management plan for upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. IVP, intravenous pyelogram; NU, nephroureterectomy.

Partial Nephrectomy

Partial nephrectomy may be a reasonable nephron-sparing strategy when an endoscopic approach is not feasible because of tumor size, tumor location (polar), or high tumor grade and stage.27 Goals of the operation must include achieving negative surgical margins and preserving residual function of the renal unit.

Segmental Ureterectomy

Tumors of the distal ureter are more common than those of the mid and proximal ureter.26 Distal ureterectomy with reimplantation is often employed for patients with high-grade, invasive, or bulky tumors of the distal ureter that are not amenable to endoscopic ablation. Depending on the length of resected ureter, this procedure may require concomitant psoas hitch or Boari bladder flap. Although the open approach has traditionally been described for distal ureteral resection, early reports of success with both laparoscopic and robotic techniques indicate that these are feasible options in selected patients.28–30

Endoscopic Management

The two alternative endoscopic approaches for lesions localized in the renal collecting system are retrograde (ureteroscopic) and antegrade (percutaneous). Choice of treatment is again influenced by lesion size, location, and focality.

Retrograde Ureteropyeloscopy

The ureteroscopic approach is usually preferred for tumors < 1.5 cm. Retrograde ureteropyeloscopy can be performed with either rigid or flexible instruments. It is important, and often difficult, to visually differentiate inflammation or guidewire trauma from carcinoma in situ (CIS) or low-grade Ta disease.31 A retrograde pyelogram is performed through a flexible ureteroscope, followed by careful ureteroscopy. The lesion is biopsied and a sample sent for pathologic analysis. Debulking of the lesion to its base is then achieved using cold-cup forceps or a stone basket. Given the thin wall of the proximal ureter and renal pelvis, no attempt should be made to resect these regions deeply. The base of the lesion is subsequently ablated using monopolar electrocautery or a surgical laser (Nd:YAG or Ho:YAG).

The principal advantages of this resection technique are low invasiveness and maintenance of a closed system, which should reduce the risk of tumor spillage.32 The small size of ureteroscopic instruments, relatively small working channels with decreased irrigant flow, and a small visual field, however, make ureteroscopic resection technically difficult. This increases the risk of overlooking multifocal tumors and performing an inadequate resection, resulting in incorrect staging and suboptimal treatment. Other disadvantages include the inability to treat large lesions in a single session, difficulty accessing lower pole lesions, and the possibility of pyelolymphatic tumor seeding.3,33

Complications of ureteroscopic management occur in 8% to 13% of cases and are mostly minor, including perforation (1%–4%) and ureteral stricture (4.9%–13.6%).34 Perforation can be managed by ureteral stenting or percutaneous drainage; strictures are often successfully managed by stenting, laser incision, or balloon dilatation. In the rare case of avulsion, immediate surgical exploration is necessary for collecting system reconstruction.

Percutaneous Nephroureteroscopy. Although more invasive than retrograde ureteroscopy, the percutaneous antegrade approach is preferred for larger tumors (> 1.5 cm) of the renal pelvis and proximal ureter.32 The advantages of this approach include the ability to use larger instruments and better visualization, facilitating complete resection of large tumors, deeper biopsies, and better staging (Figure 2). This approach also uses lower intramural pressure than ureteroscopy,35 and may be employed in patients with urinary diversions.36 The primary disadvantage of the percutaneous approach is the necessary violation of urothelial integrity and increased risk of tumor spillage. Though exceedingly rare, isolated cases of tumor seeding of the nephrostomy tract have been described.37

Figure 2.

Nephroscopic view through the resectoscope of a urothelial carcinoma prior to resection should be even with the normal mucosa to avoid injury to large superficial vessels beneath the tumor.

If there is a single tumor in a calyx, direct access into that calyx is preferred. If the tumor is in the renal pelvis or there are multiple tumors, an upper calyx is chosen for access. A percutaneous tract is established using standard techniques; it is important to use a large sheath (30 Fr or higher) to keep intrapelvic pressures at minimum. The resection is then performed in a manner similar to the ureteroscopic approach, although the percutaneous method allows for use of an electrosurgical loop for larger tumors.

Complication rates of percutaneous resection range from 21.4% to 31%,38–40 and include bleeding requiring blood transfusion (37%),7 infection, ureteropelvic junction obstruction from stricture, adjacent organ injury, and pleural injury.41

Topical Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy. Given the benefit of intravesical chemotherapy and immunotherapy in reducing recurrence and progression of superficial bladder urothelial carcinoma, one might expect a similar benefit with UTUC.42,43 However, similar efficacy has not yet been clearly demonstrated in these patients for prevention of UTUC recurrence after NSS2,6,9,17,33,38,44 or as primary treatment for upper tract CIS.45 The most common agents employed are bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), mitomycin,46 thiotepa, epirubicin,39 and BCG/interferon.47 Commonly, BCG has been instilled after percutaneous procedures, whereas mitomycin has been preferred following ureteroscopic procedures.48 The agent can be infused through a nephrostomy tube via a retrograde ureteral catheter, or by reflux from the bladder with an indwelling double-J stent. Complication rates including local skin reaction, fever (84%),45 bladder irritability, urinary tract infections, and sepsis can be significant, particularly after BCG infusion.9,38,39

Mitomycin C has limited systemic absorption and, as demonstrated by Keeley and Bagley, appears to be a safe and modestly effective adjuvant treatment in select cases.46 They reported the use of mitomycin C on 19 patients (21 renal units) who underwent ureteroscopic ablation of UTUC. With a mean followup of 30 months, 35% of renal units had a complete response, 27% had a partial response, and 38% had no response.

Numerous studies have shown decreased recurrence rates with the use of BCG.8,38,45 Positive initial response of upper tract CIS, ranging from 60% to 100%, has been reported with the use of BCG as a primary treatment.49 Martínez-Piñeiro and associates demonstrated that patients with low-grade tumors treated with BCG had a significantly lower recurrence rate: 14% versus 50% who did not receive BCG.38 When patients with CIS are excluded, however, Rastinehad and colleagues found no overall oncologic benefit to the administration of adjuvant BCG.6 Clearly, the optimal use of adjuvant intracavitary therapies for UTUC remains undefined and will be the subject of future investigations.

Oncologic Outcomes

Many studies have reported oncologic outcomes similar to radical surgery using NSS in the treatment of UTUC.

Several series have validated the efficacy of segmental ureterectomy for ureteral UTUC, consistently reporting survival and recurrence rates comparable with or better than NU.50–52 Giannarini and associates reported long-term oncologic outcomes in a retrospective analysis of 43 patients with distal tumors treated with distal ureteral resection, bladder cuff excision, and ureteral reimplantation (19 pts) and NU (24 pts).50 Patient characteristics were similar in the two groups, although the NU patients had a higher incidence of T3 and high-grade tumors, and median follow-up was 58 months. The two groups demonstrated no significant differences in survival outcomes or bladder recurrence rates. Reported 5-year overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) were 64% and 52% in NSS patients, and 66% and 56% in NU patients, respectively. Only two patients in the NSS group had a subsequent ipsilateral upper tract recurrence.

A recently published Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) database study of 2044 patients with T1–T4 N0M0 ureteral UTUC also reported noninferior outcomes at a median follow-up of 30 months in patients treated with NSS.53 Surgeries performed were segmental ureterectomy (28% of patients), NU with bladder cuff excision (60%), and NU only (12%). Median patient age, tumor grade, and tumor stage distribution were statistically similar among the three groups. CSS at 5 years was also statistically similar-71.9% for segmental ureterectomy, 67.8% for NU, and 62.2% for NU with bladder cuff. When stratified according to primary tumor stage, there was still no significant difference in CSS. Although this study was unable to assess important outcomes such as recurrence rates and progression to NU in patients undergoing segmental ureterectomy, the authors concluded that NSS did not undermine cancer control and may be extended to patients with higher-stage tumors.

Partial nephrectomy can also produce acceptable oncologic outcomes in select patients. Goel and colleagues examined their experience with partial nephrectomy in 12 patients with UTUC.54 Mean patient age was 68.5 years and mean follow-up was 40.8 months. Six patients were found to have T3 disease, 2 with T2, 3 with T1, and 1 with Tis. OS was 86%, with 42% of patients experiencing disease recurrence, and 50% demonstrating evidence of progression.

Outcomes of studies examining endoscopic resection of UTUC are summarized in Table 1. Recurrence rates for endoscopically managed UTUC range widely, from 8% to 90%.1–3,5–9,21–24,38,42,55–59 The same is true of NU rates in patients failing endoscopic ablation, reported to range from 9.5% to 40%.9,23,38,39,44,55–59 CSS and OS of approximately 80% at 5 years have been reported in the majority of large series.

Table 1.

Endoscopic Management of UTUC Series

| Study | N | Mean Patient Age (y) | Mean Tumor Size | Lesion Location | Treatment | Median Follow-up (mo) | Recurrence Rate (%) | Mean Time to Recurrence (mo) | Rate of Progression to NU (%) | CSS (% at 5 y) | OS (% at 5 y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thompson RH et al 200861 | 83 patients | 71a | 0.9 cm | 44 kidney 38 ureter 1 both | 76 URS 7 PC | 55.2 | 55.4 | 6a | 33 | 85.4 | / |

| Rastinehad and Smith 200949 | 89 renal units | 70 | / | / | PC | 40.8 | 38 for high grade | 33.8 | 20 | / | 57.8 |

| Mugiya S et al 200658 | 7 patients | 75.3 | 1.3 cm | 5 kidney 2 ureter | URS | 32b | 61.9 | / | / | / | / |

| Rouprt M et al 200759 | 24 patients | 70a | 1.8 cm | Kidney | PC | 62 | 33 | / | 21 | 79.5 | / |

| Martínez-Pieiro JA et al 199638 | 54 patients | 62.2 | / | 20 kidney 22 ureter 12 multiple | 39 URS 18 PC 2 Combined | 30.7b | 25 | / | / | / | / |

| Elliott DS et al 199662 | 44 patients | 69.1 | 1 cm | 21 kidney 23 ureter | 37 URS 7 PC | 60b | 38.6 | 12 | 15 | / | 100 for G1, 80 for G2, 60 for G3 |

| Elliott DS et al 200123 | 21 patients | 69 | 1.1 cm | 8 kidney 13 ureter | URS | 73.2b | 33 | 6.5 | 19 | / | 66 |

| Krambeck AE et al 200721 | 37 patients | 74 | 1.4 cm | / | 26 URS 8 PC 3 Combined | 32.4 | 62 | 6a | / | 49.3 | / |

| Deligne E et al 200255 | 61 patients | 66.2 | < 3 cm | 42 kidney 19 ureter | 19 URS 37 PCN 5 Combined | 39.9b | 24 | / | 9.5 | 84 | 77 |

| Jabbour ME et al 200057 | 69 patients | 69 | > 1.5 cm | / | 8 URS 61 PCN | 48 | 25 | 12 | / | 95 | / |

aMedian.

bMean.

CSS, cancer-specific survival; NU, nephroureterectomy; OS, overall survival; PC, percutaneous approach; PCN, percutaneous nephrolithotomy; URS, ureteroscopic approach; UTUC, upper tract urothelial carcinoma.

Prognostic factors for recurrence and progression in patients undergoing NSS for UTUC have been identified. Iborra and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of 54 UTUC patients with normal contralateral kidneys treated with NSS.44 On univariate and multivariate analyses, tumor location in the renal pelvis and previous multi-focal bladder tumor were the strongest risk factors for recurrence and progression. Significant risk factors observed in other studies include grade 3 histology and greater than stage pTa tumors.57,60

Cost

From a cost perspective, NSS for management of UTUC is effective in reducing end-stage renal disease health care expenses. A recent study on 57 patients with UTUC analyzed the direct costs of endoscopic ablation versus NU/hemodialysis on patients with a solitary kidney.56 At 2-year follow-up, renal preservation was achieved in 81% of patients, with a CSS of 94.7%. The direct costs were calculated for ureteroscopic laser treatments, diagnostic ureteroscopy, laparoscopic NU with bladder cuff, and hemodialysis. In patients with imperative indications for renal preservation, the cost savings over a 5-year period ranged from three-fold to almost ten-fold when compared with the radical surgery cohort.

Conclusions

Nephron-sparing approaches to the management of UTUC, including endoscopic ablation, are safe and effective when applied to selected patients. Ideal candidates should have small, unifocal, low-grade, Ta lesions, and patients meeting these criteria with a normal contralateral kidney should not be excluded from consideration. Benefits of endoscopic management include decreased surgical morbidity and renal preservation in the majority of cases, resulting in significantly reduced health care costs. Larger or higher-grade tumors may be treated endoscopically depending on the ability of the surgeon to achieve a complete resection, especially in patients with imperative indications, although recurrence and progression rates will be higher.

Main Points.

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) accounts for < 5% of all cases of urothelial neoplasia, but is a very morbid disease, with recurrence rates up to 90% and 5-year survival rates ranging from 30% to 60%.

Tumor grade, focality, size, and location should all be considered when selecting patients for nephron-sparing surgery (NSS). Given the difficulties in establishing depth of invasion, and the significant correlation between tumor grade and stage, tumor grade is a very important factor for predicting the aggressiveness of UTUC.

Of all UTUCs, approximately 75% are located in the collecting system of the kidney, and the remaining 25% occur in the ureter. Nephron-sparing approaches to the management of UTUC, including endoscopic ablation, are safe and effective when applied to select patients. Options for NSS depend on tumor location and size, and include partial nephrectomy, segmental ureterectomy, and endoscopic resection.

Benefits of endoscopic management include decreased surgical morbidity and renal preservation in the majority of cases, resulting in significantly reduced health care costs. Larger or higher-grade tumors may be treated endoscopically depending on the ability of the surgeon to achieve a complete resection, especially in patients with imperative indications, although recurrence and progression rates will be higher.

References

- 1.Chen GL, Bagley DH. Ureteroscopic management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma in patients with normal contralateral kidneys. J Urol. 2000;164:1173–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daneshmand S, Quek ML, Huffman JL. Endoscopic management of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: long-term experience. Cancer. 2003;98:55–60. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeley FX , Jr, Bibbo M, Bagley DH. Ureteroscopic treatment and surveillance of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1997;157:1560–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy DM, Zincke H, Furlow WL. Primary grade 1 transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis and ureter. J Urol. 1980;123:629–631. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee BR, Jabbour ME, Marshall FF, et al. 13-year survival comparison of percutaneous and open nephroureterectomy approaches for management of transitional cell carcinoma of renal collecting system: equivalent outcomes. J Endourol. 1999;13:289–294. doi: 10.1089/end.1999.13.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rastinehad AR, Ost MC, Vanderbrink BA, et al. A 20-year experience with percutaneous resection of upper tract transitional carcinoma: is there an oncologic benefit with adjuvant bacillus Calmette Guérin therapy? Urology. 2009;73:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark PE, Streem SB, Geisinger MA. 13-year experience with percutaneous management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1999;161:772–775. discussion 775–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasavada SP, Streem SB, Novick AC. Definitive tumor resection and percutaneous bacille Calmette-Guérin for management of renal pelvic transitional cell carcinoma in solitary kidneys. Urology. 1995;45:381–386. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabbour ME, Smith DA. Primary percutaneous approach to upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am. 2000;27:739–750. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Poel HG, Antonini N, Van Tinteren H, Horenblas S. Upper urinary tract cancer: location is correlated with prognosis. Eur Urol. 2005;48:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:735–740. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Eng J Med. 2004;351:1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churchill DN, Torrance GW, Taylor DW, et al. Measurement of quality of life in end-stage renal disease: the time trade-off approach. Clin Invest Med. 1987;10:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodkin DA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Koenig KG, et al. Association of comorbid conditions and mortality in hemodialysis patients in Europe, Japan and United States: the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:3270–3277. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000100127.54107.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babaian RJ, Johnson DE. Primary carcinoma of the ureter. J Urol. 1980;123:527. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen GL, El-Gabry , Bagley DH. Surveillance of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: the role of ureteroscopy, retrograde pyelography, cytology and urinanalysis. J Urol. 2000;161:783. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)66913-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liatsikos EN, Dinlenc CZ, Kapoor R, Smith AD. Transitional-cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis: ureteroscopic and percutaneous approach. J Endourol. 2001;15:377–383. doi: 10.1089/089277901300189385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zincke H, Aguilo JJ, Farrow GM, et al. Significance of urinary cytology in the early detection of transitional cell cancer of the upper urinary tract. J Urol. 1976;116:781–783. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)59010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grace DA, Taylor WN, Taylor JN, Winter CC. Carcinoma of the renal pelvis: a 15-year review. J Urol. 1967;98:566–569. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)62933-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Hakim A, Weiss GH, Lee BR, Smith AD. Correlation of ureteroscopic appearance with histologic grade of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology. 2004;63:647–650. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.076. discussion 650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krambeck AE, Thompson HR, Lohse CM, et al. Imperative indications for conservative management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;178:792–797. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.056. discussion 796–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milner JE, Voelzke BB, Flanigan RC, et al. Urothelial-cell carcinoma and solitary kidney: outcomes with renalsparing management. J Endourol. 2006;20:800–807. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott DS, Segura JW, Lightner D, et al. Is nephroureterectomy necessary in all cases of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma? Long-term results of conservative endourologic management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma in individuals with a normal contralateral kidney. Urology. 2001;58:174–178. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palou J, Piovesan LF, Huguet J, et al. Percutaneous nephroscopic management of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: recurrence and long-term follow-up. J Urol. 2004;172:66–69. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132128.79974.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall MC, Womack S, Sagalowsky AI, et al. Prognostic factors, recurrence and survival in transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: a 30-year experience in 252 patients. Urology. 1998;52:594–601. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babaian RJ, Johnson DE. Primary carcinoma of the ureter. J Urol. 1980;123:357–359. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goel MC, Matin SF, Derweesh I, et al. Partial nephrectomy for renal urothelial tumors: clinical update. Urology. 2006;67:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roupr\ et, Harmon JD, Sanderson KM, et al. Laparoscopic distal ureterectomy and anastomosis for management of low-risk upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: preliminary results. Br J Urol. 2007;99:623–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uberoi J, Harnisch B, Sethi AS, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic distal ureterectomy and ureteral reimplantation with psoas hitch. J Endourol. 2007;21:368–373. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.9970. discussion 373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazeman E. Tumors of the upper urinary tract calyces, renal pelvis, and ureter. Eur Urol. 1976;2:120–126. doi: 10.1159/000471981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crouzet S, Berger A, Monga M, Desai M. Ureteroscopic management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma and ureteropelvic obstruction. Indian J Urol. 2008;24:526–531. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.44262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raman JD, Scherr DS. Management of patients with upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007;4:432–443. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen GL, Bagley DH. Ureteroscopic surgery for upper tract transitional-cell carcinoma: complications and management. J Endourol. 2001;15:399–404. doi: 10.1089/089277901300189420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soderdahl DW, Fabrizio MD, Rahman NU, et al. Endoscopic treatment of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2005;23:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scoffone CM, Cracco CM, Poggio M, et al. Treatment of the pyelocalyceal tumors with laser. Arch Esp Urol. 2008;61:1080–1087. doi: 10.4321/s0004-06142008000900018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irwin BH, Berger AK, Brandina R, et al. Complex percutaneous resections for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Endourol. 2010;24:367–370. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang A, Low RK, deVere White R. Nephrostomy tract tumor seeding following percutaneous manipulation of a ureteral carcinoma. J Urol. 1995;153:1041–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez-Piñeiro JA, García Matres MJ, Martínez-Piñeiro L. Endourological treatment of upper tract urothelial carcinomas: analysis of a series of 59 tumors. J Urol. 1996;156(2 Pt 1):377–385. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199608000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goel MC, Mahendra V, Roberts JG. Percutaneous management of renal pelvic urothelial tumors: longterm followup. J Urol. 2003;169:925–929. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000050242.68745.4d. discussion 929–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jarrett TW, Sweetser PM, Weiss GH, Smith AD. Percutaneous management of transitional cell carcinoma of the renal collecting system: 9-year experience. J Urol. 1995;154:1629–1635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Argyropoulos AN, Tolley DA. Upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: current treatment overview of minimally invasive approaches. BJU Int. 2007;99:982–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huncharek M, Geschwind JF, Witherspoon B, et al. Intravesical chemotherapy prophylaxis in primary superficial bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of 3703 patients from 11 randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:676–680. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huncharek M, McGarry R, Kupelnick B. Impact of intravesical chemotherapy on recurrence rate of recurrent superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: results of a meta-analysis. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:765–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iborra I, Solsona E, Casanova J, et al. Conservative elective treatment of upper urinary tract tumors: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for recurrence and progression. J Urol. 2003;169:82–85. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thalmann GN, Markwalder R, Walter B, Studer UE. Long-term experience with bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma in patients not eligible for surgery. J Urol. 2002;168:1381–1385. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keeley FX , Jr, Bagley DH. Adjuvant mitomycin C following endoscopic treatment of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1997;158:2074–2077. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)68157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katz MH, Lee MW, Gupta M. Setting a new standard for topical therapy of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma: BCG and interferon-alpha2b. J Endourol. 2007;21:374–377. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.9969. discussion 377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tawfiek ER, Bagley DH. Upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology. 1997;50:321–329. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rastinehad A, Smith A. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin for upper tract urothelial cancer: is there a role? J Endourol. 2009;23:563–568. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giannarini G, Schumacher MC, Thalmann GN, et al. Elective management of transitional cell carcinoma of the distal ureter: can kidney-sparing surgery be advised? BJU Int. 2007;100:264–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zungri E, Chéchile G, Algaba F, et al. Treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter: is the controversy justified? Eur Urol. 1990;17:276–280. doi: 10.1159/000464059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderstrom C, Johansson SL, Pettersson S, Wahlquist L. Carcinoma of the ureter: a clinicopathologic study of 49 cases. J Urol. 1989;142:280–283. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeldres C, Lughezzani G, Sun M, et al. Segmental ureterectomy can safely be performed in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter. J Urol. 2010;183:1324–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goel MC, Matin SF, Derweesh I, et al. Partial nephrectomy for renal urothelial tumors: clinical update. Urology. 2006;67:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deligne E, Colombel M, Badet L, et al. Conservative management of upper urinary tract tumors. Eur Urol. 2002;42:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pak RW, Moskowitz EJ, Bagley DH. What is the cost of maintaining a kidney in upper-tract transitional-cell carcinoma? An objective analysis of cost and survival. J Endourol. 2009;23:341–346. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jabbour ME, Desgrandchamps F, Cazin S, et al. Percutaneous management of grade II upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: the long-term outcome. J Urol. 2000;163:1105–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mugiya S, Ozono S, Nagata M, et al. Retrograde endoscopic laser therapy and ureteroscopic surveillance for transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. Int J Urol. 2006;13:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roupr\ et, Traxer O, Tligui M, et al. Upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: recurrence rate after percutaneous endoscopic resection. Eur Urol. 2007;51:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.019. discussion 714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson RH, Krambeck AE, Lohse CM, et al. Elective endoscopic management of transitional cell carcinoma first diagnosed in the upper urinary tract. BJU Int. 2008;102:1107–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson RH, Krambeck AE, Blute M. Endoscopic management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma in patients with normal contralateral kidneys. Urology. 2008;71:713–717. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elliott DS, Blute ML, Patterson DE, et al. Long-term follow-up of endoscopically treated upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology. 1996;47:819–825. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00043-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]