Abstract

Temporarily implanted devices, such as drug-loaded contact lenses, are emerging as the preferred treatment method for ocular diseases like glaucoma. Localizing the delivery of glaucoma drugs, such as timolol maleate (TM), can minimize adverse effects caused by systemic administration. Although eye drops and drug-soaked lenses allow for local treatment, their utility is limited by burst release and a lack of sustained therapeutic delivery. Additionally, wet transportation and storage of drug-soaked lenses result in drug loss due to elution from the lenses. Here we present a nanodiamond (ND)-embedded contact lens capable of lysozyme-triggered release of TM for sustained therapy. We find that ND-embedded lenses composed of enzyme-cleavable polymers allow for controlled and sustained release of TM in the presence of lysozyme. Retention of drug activity is verified in primary human trabecular meshwork cells. These results demonstrate the translational potential of an ND-embedded lens capable of drug sequestration and enzyme activation.

Keywords: nanomedicine, contact lens, nanodiamond, drug delivery, biomaterials

Glaucoma will affect approximately 79.6 million people worldwide by 2020.1 Although there are a variety of nonsurgical treatment options, one of the biggest barriers to treatment success is patient compliance.2 Recent advances in the design of biomaterials aim to improve drug delivery by controlling the timing and location of drug release.3−6 These advances are being adapted to ocular drug delivery systems that may improve patient adherence through the use of therapeutic contact lenses.7−9 Unlike eye drops and drug-soaked lenses, which show burst release profiles, novel contact lenses made through molecular imprinting or embedded microparticles maintain a local therapeutic dosage for a longer time.10−13 Utilizing these types of therapeutic contact lenses would lead to lower required dosage and less frequent drug application, thereby improving patient adherence.

A clinically effective drug delivery system must also address the challenges of commercial manufacturing and distribution. Most soft contact lenses, made of poly-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (polyHEMA), must be shipped and stored wet to avoid becoming brittle. However, this can cause drug-loaded contact lenses to elute drugs prematurely, rendering the drug delivery system ineffective. This has necessitated the development of smarter delivery systems, which release their therapeutic payload under artificial or biological stimuli.14−17 One potential biological stimulus is lysozyme, an enzyme in lacrimal fluid capable of catalyzing the hydrolysis of 1,4-β-glycosidic bonds in peptidoglycans and chitodextrins.18 The goal of this work is to develop a lysozyme-triggered drug delivery system capable of delivering a drug in a controlled fashion.

Recently, nanomaterials have mediated marked advances in biomedical imaging and drug delivery.19−27 In particular, nanoparticles are effective vehicles for ocular delivery of bioactive molecules, such as small molecule therapeutics and nucleic acids.28 Uniquely faceted detonation nanodiamond (ND) particles have been utilized for numerous applications in biomedical imaging, sensing and therapeutic delivery.29−32 The uniquely faceted surface architecture of NDs enables particle dispersal, coordinates water molecules around the surface, and allows potent and reversible drug binding. These mechanisms have mediated marked improvements to applications such as drug delivery and biomedical imaging in multiple models.31,33−35 In addition to being highly effective nanocarriers, ND biocompatibility has been observed in many in vitro and in vivo studies.31,33,36 Comparing controls and mice treated with high doses of NDs or NDs carrying chemotherapeutics, there are no significant differences in hematological or serum markers of inflammation and toxicity.33 Additionally, histological analysis of the kidney, liver and spleen found no differences between NDs and PBS controls.31 Although the ocular compatibility of NDs has not been evaluated, carbon nanohorns, a related and similarly sized material, do not induce any clinical abnormalities on eye irritation tests in rabbits.37

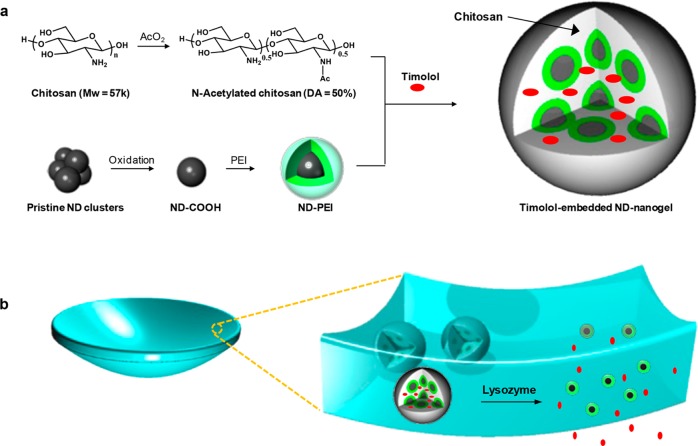

Nanodiamonds have previously been incorporated into polymer matrices to improve mechanical properties and/or elute therapeutic compounds.38−40 In addition, previous reports have demonstrated the ability to create and utilize optically transparent ND films.41 These developments support the fabrication of an ND-based contact lens for controlled delivery of ocular therapeutics. In the design presented in this work, individual NDs are coated with polyethyleneimine (PEI) and then cross-linked with an enzyme-cleavable polysaccharide, chitosan, forming a ND-nanogel loaded with timolol maleate (TM) (Figure 1a). These ND-nanogels are then embedded within a polyHEMA matrix and cast into contact lenses (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of our lysozyme-activated drug eluting contact lens. (a) Drug-loaded ND-nanogels are synthesized by cross-linking PEI-coated NDs and partially N-acetylated chitosan (MW = 57 kDa; degree of N-acetylation = 50%) in the presence of timolol maleate. The ND-nanogels are then embedded in a hydrogel and cast into enzyme-responsive contact lenses. (b) Exposure to lacrimal fluid lysozyme cleaves the N-acetylated chitosan, degrading the ND-nanogels and releasing the entrapped timolol maleate while leaving the lens intact.

Results and Discussion

ND-Nanogel Synthesis and Characterization

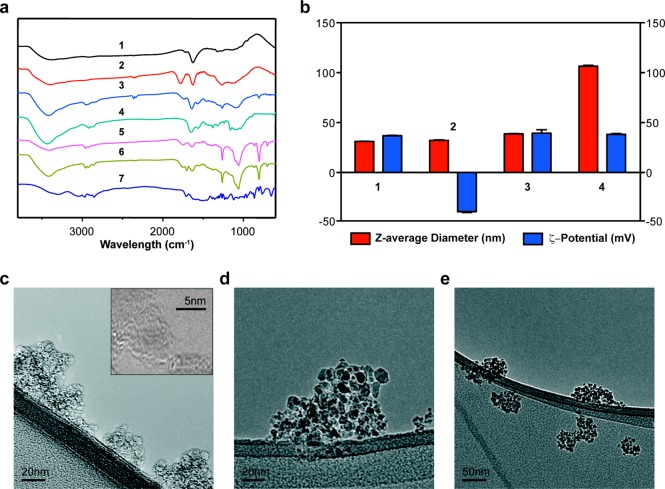

For optimal contact lens fabrication and to ensure clinical-grade optical clarity, the NDs must be well dispersed in the gel matrix. Electrostatic and covalent interactions, which are mediated by surface graphitic carbon, cause primary diamond particles (∼5 nm) to spontaneously form clusters of up to 200 nm. The graphitic carbon can be eliminated by oxidation in air at 420 °C.42,43 In addition, this method improves the homogeneity of the surface chemical groups, converting them into carboxylic acids and cyclic acid anhydrides.44 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra of the heat-treated NDs shows a C=O stretching peak from carboxylic acid at 1775 cm–1, indicating successful oxidation (Figure 2a). ζ-potential measurement shows a shift from an average of +36.8 mV for the pristine NDs to −40.7 mV for the air oxidized NDs due to surface carboxylic acid groups (Figure 2b). The air oxidized NDs, which form a stable colloidal solution, have an average particle size of 32.2 nm on dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Characterization of ND-nanogel during synthesis. (a) FT-IR spectra of (1) pristine ND, (2) oxidized ND, (3) ND-PEI, (4) N-acetylated chitosan, (5) ND-nanogel, (6) timolol [TM]-loaded ND-nanogel, and (7) timolol. (b) Particle size (red-colored bars) and ζ-potential (blue-colored bars) distributions of (1) pristine ND, (2) oxidized ND, (3) ND-PEI, and (4) TM-loaded ND-nanogel. TEM images of (c) pristine ND, (d) ND-PEI, and (e) TM-loaded ND-nanogel.

To increase the surface density and accessibility of reactive groups, the oxidized NDs are then coated with highly branched PEI-800 using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS). FTIR of the ND-PEI is indicative of covalent attachment of ND-surface carboxylic acids to amines on the PEI, showing peaks at 3380, 2950, 2825, 1640, and 1560 cm–1 (Figure 2a). Compared to oxidized NDs, ND-PEI show a slight increase in size (∼6 nm) and a change in the average ζ-potential to +39.4 mV (Figure 2b). Furthermore, comparing the TEM images of pristine NDs and ND-PEI shows that ND-PEI particles are larger, smoother and more electron-dense than the pristine particles (Figure 2c,d). This work presents a novel method for dispersion and stabilization of reactive NDs in water, facilitating the biological or chemical functionalization of NDs.

The next step in the production of the ND-embedded contact lens is the synthesis of the ND-nanogels by cross-linking ND-PEI clusters with N-acetylated chitosan to form a lysozyme degradable nanogel. Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide composed of d-glucosamine and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine coupled with 1,4-β-glycosidic bonds that can be cleaved by lysozyme. The rate at which chitosan is degraded by lysozyme is dependent on the degree of acetylation (DA), with increased acetylation associated with more rapid degradation.45 Prior to coupling to ND-PEI, chitosan is acetylated to 50% DA (elemental analysis) using acetic acid according to the protocol by Ren et al.(45) (Supporting Information Figure S1). ND-PEI is first modified with succinic anhydride and then coupled to acetylated chitosan using EDC/NHS in the presence of TM. This generates the drug-encapsulated, enzyme-cleavable ND-nanogels. Although the chitosan could have been directly coupled to the ND surface, the PEI layer allows for more effective lysozyme cleavage and TM release. FTIR analysis of the ND-nanogel demonstrates the characteristic peaks for amide bonds and amines, which is consistent with the presence of chitosan and PEI (Figure 2a). For the ND-nanogels, the peaks for amide bonds and primary amine groups from chitosan cannot be distinguished because they overlap with the characteristic peaks of PEI. The entrapment of drug is confirmed by the presence of characteristic peaks for TM at 2967, 2853, 1705, and 1375 cm–1 (Figure 2a). In addition, DLS data demonstrates that the ND-nanogels have an average diameter of 106.5 nm (Figure 2b), which is consistent with TEM images showing that each nanogel is a network of individual NDs (Figure 2e).

Contact Lens Synthesis and Characterization

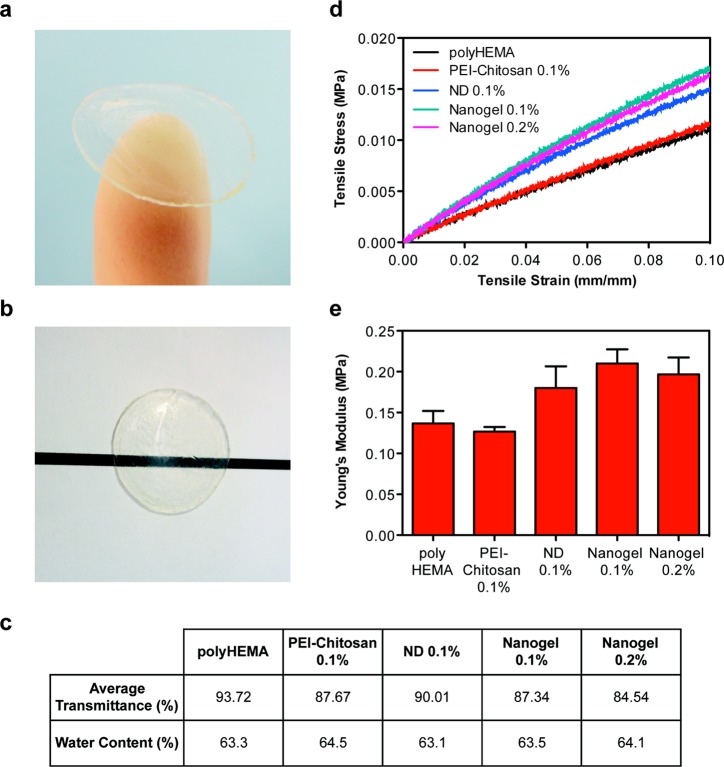

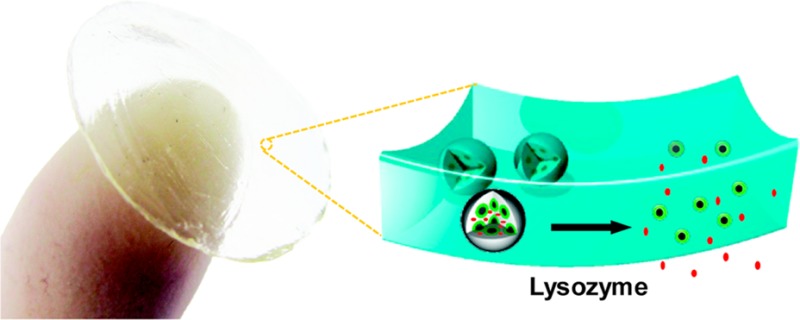

To serve as an effective ocular drug delivery platform, the ND-nanogels are incorporated into a polyHEMA matrix and cast into contact lenses (Figure 3a). Briefly, the drug-loaded ND-nanogels were dispersed by ultrasonication in a solution of HEMA before adding methacrylic acid (5% v/v), ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (0.25% v/v) and a photoinitiator (Darocur, 0.2% v/v). This composition is commonly used to make soft contact lenses and has an average pore size of 34.7 Å,43 which is suitable for lysozyme (30 × 30 × 45 Å) penetration. In addition to porosity, the optical clarity and water content of polyHEMA gels make them ideal for soft contact lenses. The addition of the ND-nanogels to polyHEMA does not induce any visible alterations in the lens optical characteristics (Figure 3b). The polyHEMA contact lens shows an average transmission of 93.8% prior to ND-nanogel loading. The addition of 0.1% pristine ND, 0.1% ND-nanogel or 0.2% ND-nanogel does not lower this average transmission by more than 10% (Figure 3c). The 0.2% ND-nanogel shows a transmittance of 84.5%.

Figure 3.

Characterization of physical properties of contact lenses. (a) ND-nanogels can be embedded into polyHEMA gels and cast into contact lenses. (b) ND-nanogel embedded lenses maintain optical transparency. (c) Comparison of average visible light transmittance (400–700 nm) and water content of polyHEMA lenses without additives, with 0.1% (w/w) PEI-chitosan, with 0.1% (w/w) pristine ND, with 0.1% (w/w) ND-nanogel or 0.2% (w/w) ND-nanogel. (d) Tensile stress–strain curves comparing polyHEMA lenses without additives, with 0.1% (w/w) PEI-chitosan, with 0.1% (w/w) pristine ND, with 0.1% (w/w) ND-nanogel or 0.2% (w/w) ND-nanogel. (e) Young’s modulus of the polyHEMA lenses without additives, with 0.1% (w/w) PEI-chitosan, with 0.1% (w/w) pristine ND, with 0.1% (w/w) ND-nanogel or 0.2% (w/w) ND-nanogel, as determined by the first 5% of the stress–strain curve slope.

Another important parameter in the design of therapeutic contact lenses is water content. In addition to affecting lysozyme penetration and drug elution, water content dictates the oxygen permeability of the lens. Adding ND-nanogels, pristine NDs or PEI-chitosan causes little impact on the water content of the lens, with values ranging from 63.3% to 64.5% (Figure 3c). Additionally, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) shows that the surfaces of polyHEMA and ND-nanogel embedded lenses are similar (Supporting Information Figure S2). The only observable difference between the two lenses is the presence of approximately 100 nm ND-nanogels on the drug eluting lens surface. Given that the additives comprise only 0.1% (w/w) of the total lens mass, it is expected that the bulk characteristics of the gel would remain largely unchanged.

As contact lenses are subjected to innumerable mechanical stresses during the course of insertion, use and removal, the mechanical properties of the lens matrix are important design considerations. Previous reports on polymer matrices with embedded NDs have demonstrated an enhancement in mechanical properties with the addition of a small amount of diamond.29 Tensile testing of the contact lenses demonstrates that the addition of 0.1% (w/w) pristine NDs to the polyHEMA lens boosts the Young’s modulus by 31% (Figure 3d,e). The contact lenses containing the drug-loaded ND-nanogels (0.1 and 0.2% w/w) show 40–50% improvement in Young’s modulus up to approximately 0.2 MPa. In contrast, the control lenses containing PEI-Chitosan (0.1% w/w) show no alteration in mechanical properties. Combined, these results indicate that the incorporation of ND particles into the contact lens reinforces the polymer matrix, improving tensile strength and boosting elastic modulus. At 0.2 MPa, the ND-embedded hydrogels are still less stiff than commercial polyHEMA lenses (∼0.5 MPa). The lack of professional lens fabrication equipment may explain this discrepancy. Nevertheless, NDs make an attractive lens nanofiller due to their ability to improve tensile strength without altering overall lens thickness. Soft contact lens design is a challenging balancing act between lens mechanical strength and oxygen diffusion. Thicker lenses are stronger but they limit the amount of oxygen that reaches the cornea. By incorporating NDs into the lens matrix, more durable lenses could be produced without sacrificing lens thickness or user comfort.

Enzyme-Triggered Drug Delivery

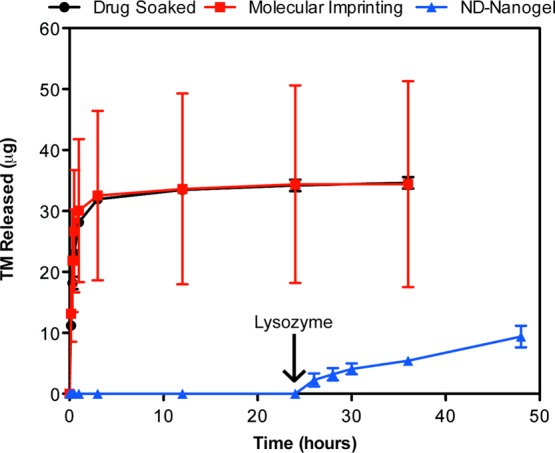

While the ND-nanogels improve matrix mechanical properties, the end goal of these studies is to produce a contact lens that releases TM in a controlled manner. To this end, the elution of TM was studied in three different types of contact lenses: ND-nanogel lenses, TM-soaked lenses and molecularly imprinted lenses.9 TM released from contact lenses was first purified by HPLC and then quantified using its absorbance in the visible range. Both the drug-soaked and molecularly imprinted contact lenses show almost complete release of TM within the first hour (Figure 4). In contrast, in the absence of lysozyme, TM release from the ND-nanogel lens is undetectable. After treatment with lysozyme, the cumulative drug release from the ND-nanogel lens is 9.41 μg over 24 h (Figure 4). Some variability in the TM release profile, including some burst release, is observed after 48 h of lysozyme treatment. This is likely due to variation in the size and depth of ND-nanogels within the polymer matrix and could likely be eliminated with minimal optimization and the utilization of commercial-grade lens fabrication equipment. However, the behavior after 48 h is less concerning because therapeutic lenses are commonly worn for a 24-h period. Additionally, TM release is not associated with ND release from the lens, as determined by tracking fluorescently labeled ND-PEI (Supporting Information Figure S3). Although NDs have previously been shown to be biocompatible, the stable retention of NDs is an additional safety assurance to users.

Figure 4.

Enzyme-triggered drug release. Drug-eluting profiles from drug-soaked (black line), molecularly imprinted (red line) and ND nanogel-embedded contact lenses (blue line) in saline solution at 37 °C as determined by HPLC analysis of TM. Lysozyme (2.7 mg/mL) in PBS was added after 24 h of incubation (N = 3 for each type of lens).

For the ND-nanogel lens to find clinical utility, it must be able to elute a sufficient amount of drug over 24 h. The recommended starting dosage of TM is 2 drops of 0.25% solution per day. Assuming a typical eye drop volume of 25 μL and bioavailability of 1%, the total dosage would be 1.7 μg/day.46 Because the thickness of the lenses generated here are 7-times as thick as a standard contact lens (700 μm vs 100 μm) the amount of drug released must be scaled. Taking the fractional mass released as inversely proportional to the square of the lens thickness, the commercial version of the ND-nanogel lens will release about 0.192 μg/day or 11.3% of the standard dosage. However, a recent pharmacodynamics study using dogs showed that drug-soaked lenses releasing 20% of the standard eye drop dosage are capable of achieving the same efficacy as the eye drops.47 Hence, further optimization of the ND-nanogel lens would produce a clinically relevant and commercially viable product.

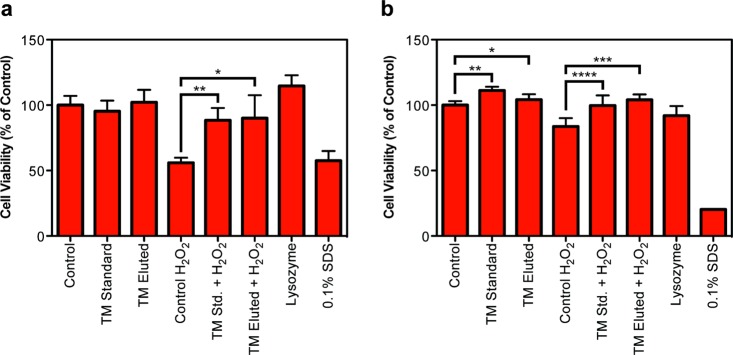

Biological Activity of Released Drug

To produce a functional drug delivery system, the TM released from the lens must retain its activity. Confirmation of the biological activity of TM is determined based on its antioxidant capacity.48 Pretreatment of primary human trabecular meshwork cells with TM will protect cells against oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. The heterogeneous nature of primary cells serves as suitable test bed for ND-lens efficacy. Cell viability is assessed using two separate assays – absorbance-based XTT, which measures mitochondrial enzyme activity, and fluorescence-based CellTiter-Blue, which measures mitochondrial, cytoplasmic and microsomal enzyme activity. Cells pretreated with TM eluted from the ND-nanogel embedded contact lens (1 μg/mL) or a standard solution of TM (1 μg/mL) prior to the addition of hydrogen peroxide show improved viability using both the XTT (Figure 5a, p < 0.005) and CellTiter-Blue (Figure 5b, p < 0.0005) assays. Importantly, there is no difference in cell viability between the standard and lens-eluted TM.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of TM using primary human trabecular meshwork cells. Cells were treated with control, standard TM (1 μg/mL) or ND-nanogel-eluted TM (1 μg/mL) prior to incubation with 20 μM H2O2 to induce oxidative cell death. (a) XTT cell viability assay (N = 8; *p = 4.2 × 10–8, **p = 6.0 × 10–5). (b) CellTiter-Blue cell viability assay (N = 6; *p = 0.033, **p = 1.0 × 10–6, ***p = 3.3 × 10–5, ****p = 0.0024).

Conclusion

These studies have demonstrated that the ND-nanogel embedded contact lens serves as an effective device for the enzyme-triggered delivery of timolol (TM). The ND-nanogels sequester TM prior to lysozyme activation and subsequently allow sustained drug release. This eliminates the uncontrolled release observed with other lens types, thus facilitating large-scale manufacturing, storage and distribution. As a nanofiller, ND also improves the mechanical properties of our lens. Optical clarity, water content and oxygen permeability are maintained at practical levels. Most importantly, eluted TM from our ND-nanogel lens retains drug activity as verified by an in vitro model.

In addition, this work has provided a new method for generating a stable, aqueous colloid of reactive NDs through the covalent conjugation of PEI. ND-PEI can be readily functionalized using aqueous chemistry, making it ideal for reactions where organic solvents cannot be used.

The system developed here, based on NDs, provides a new platform for the development of hydrogels capable of enzyme-triggered drug release. The contact lens device is capable of mediating therapeutic elution from the ND-nanogel via lysozyme-dependent polysaccharide degradation. Since drug loading is achieved by entrapment, therapeutics other than TM can be easily incorporated for lysozyme-triggered delivery for the eye and other regions. Furthermore, the same approach can be applied to other biological systems by replacing chitosan with a different enzyme-cleavable polysaccharide. This polysaccharide can be conjugated to the ND surface via similar facile synthesis method. By utilizing NDs in this novel approach to enzyme-triggered drug delivery, we are able to achieve enhanced mechanical performance in addition to effective drug delivery. Notably, nanodiamonds, which are byproducts of existing mining and refining operations, can be processed into uniform particles with truncated octahedral structures using straightforward methodologies like ball milling, acid washing, and ultrasonication. Therefore, their availability and scalability make them favorable materials for the synthesis of therapeutic contact lenses and other drug-eluting materials.

Materials and Methods

Preparation and Characterization of Timolol-Loaded ND-Nanogel

N-Acetylation of chitosan (Chitosan-10, degree of acetylation (DA) 15%, MW = 57 kDa, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) was performed as previously described.45 Chitosan was first dissolved in 3% (v/v) acetic acid solution before the addition of methanol. Acetic anhydride was added to this solution, stirred at room temperature overnight and then neutralized with 1 mol/L NaOH to yield a white precipitate. The collected precipitate was washed with water in wash/centrifugation cycles and lyophilized to give a white powder. The degree of N-acetylation (DA) of chitosan was calculated from elemental analysis.

Freeze-dried pristine NDs were air oxidized at 420 °C for 2.5 h. The NDs were then dissolved in anhydrous DMSO and ultrasonicated for 30 min. EDC (Sigma) and NHS (Sigma) were added to the oxidized NDs in DMSO. After stirring for 1 h, excess polyethylenimine (PEI, MW = 800, Sigma) was added to the solution and it stirred overnight. The product was washed with water in consecutive washing/centrifugation cycles. ND-PEIs were conjugated with excess succinic acid to yield carboxylated ND-PEIs. Amide cross-linking reaction was performed between N-acetylated chitosan and NHS-activated ND-PEI in the presence of timolol, yielding timolol-loaded ND-nanogel. All functionalized NDs were confirmed by FTIR (Nexus 870 spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet)). TEM images were taken using a 200 kV JEOL JEM-2100F TEM. Hydrodynamic size and ζ-potential measurements were performed using Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, U.K.) with NDs in deionized water at 50 μg/mL.

Preparation of ND-Embedded Contact Lenses

The contact lenses were prepared by free-radical copolymerization. ND-nanogels were suspended in 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA, Sigma) solution before the addition of methacrylic acid (MAA, 5% v/v, Sigma), ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, 0.25% v/v, Sigma) and 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone (Darocur photoinitiator, 0.2% v/v, Sigma). The monomer solution was poured into an aluminum mold with 0.50 mm center thickness. Polymerization was initiated with UV irradiation (6.5 mW/cm2 at 365 nm). The gel was soaked in deionized water for 4 h and discs (12 mm diameter) were punched out with a cork borer. The lenses were then immersed in 0.9% NaCl solution for 2 days to remove unreacted monomers and initiator. Molecularly imprinted contact lenses and drug-soaked lenses were manufactured as previously described.9 Drug loading was done by soaking in 0.02 mM of timolol solution for 3 days.

Characterization of Contact Lenses

NDs were imaged on a 200 kV JEOL JEM-2100F TEM. NDs (5 μg/mL) in deionized water were pipetted onto lacey carbon on copper TEM grids (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) and the solvent was removed after deposition for 3 min. SEM images were obtained using a Hitachi S-4800-II. Samples were lyophilized before being coated twice with 5 nm thick OsO4 using an osmium plasma coater (Structure Probe, Inc.). Rectangular specimens were placed on Instron 5533 and tested with three 10% length preload cycle stretches before an ultimate strength test. The modulus of elasticity of each lens was calculated by using the initial 5% slope from the stress–strain graph. The water content of contact lenses was calculated by the ratio of the weight of water in the hydrogel to the total weight of the hydrogel.

Determining Timolol-Release Profiles

The release of timolol at 37.8 °C from hydrogels was measured in triplicates over 72 h in 5 mL of saline or artificial lacrimal fluid (6.78 g/L NaCl, 2.18 g/L NaHCO3, 1.38 g/L KCl, 0.084 g/L CaCl2, pH 7.2). Timolol-release profile was carried out using a Varian high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Milford, MA). A mixture of 0.1 M PBS (pH 2.8)/methanol (40:60) delivered at 1.0 mL/min was used as the mobile phase. The peak area at 295 nm was used for calculation.

Culturing of Human Trabecular Meshwork Cells (HTM)

Primary HTM cells (P10879, Innoprot) were propagated in fibroblast growth medium-2 (CC-3132 Lonza) with the provided supplement kit and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). At 80% confluence, the cells were trypsinized for subculturing or for experiment. After 4 days of lysozyme addition to the hydrogel, the eluate, which contained timolol, was used for the experiments.

Determination of Cell Viability via XTT Assay

The eluate was diluted to a timolol concentration of 1 μg/mL before being applied to the HTM cells (P5) for 10 min. Hydrogen peroxide (0.2 μM) was then applied for 15 min. The XTT media was prepared by adding 1.5 mL of XTT (Invitrogen) solution (1 mg/mL XTT in PBS) and 6.46 μL of menadione (Enzo Life Sciences, 10 mg/mL ethanol) to 8.5 mL of media. For the assay, 50 μL of XTT media was added to 100 μL of fresh media in each well. PBS washing was done once in between these steps. The plate was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C, shaken and read at 450 nm with a spectrophotometer. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the control wells.

Determination of Cell viability via CellTiter-Blue Assay

The eluate was diluted to a timolol concentration of 1 μg/mL before being applied to the HTM cells (P4) for 10 min. Hydrogen peroxide (20 μM) was then applied for 30 min. A volume of 20 μL CellTiter-Blue (Promega) was then added to each well containing 100 μL of media. The plate was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C and read at 560 nm/590 nm (emission/excitation). Cell viability is expressed as a percentage of the control wells.

Statistical Methods

All statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel. All p-values were obtained using two-tailed students t test with a minimum of 6 replicates.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation CAREER Award (CMMI-0846323), Center for Scalable and Integrated NanoManufacturing (DMI-0327077), CMMI-0856492, DMR-1105060, V Foundation for Cancer Research Scholars Award, Wallace H. Coulter Foundation Translational Research Award, Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening (SLAS) Endowed Fellowship, Beckman Coulter, and National Cancer Institute Grant U54CA151880. (The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health). K. Zhang gratefully acknowledges individual fellowship support provided by Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR). L. Moore gratefully acknowledges individual fellowship support from the National Cancer Institute (1F30CA174156).

Supporting Information Available

FT-IR spectra of chitosan and N-acetylated chitosan; SEM images of HEMA lens and ND-nanogel embedded lens; fluorescence spectral scan to detect dye-labeled NDs in eluted lens solution. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Author Present Address

∇ Division of Oral Biology and Medicine and Division of Advanced Prosthodontics, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles, California, 90095.

Author Present Address

⊗ The Jane and Jerry Weintraub Center for Reconstructive Biotechnology, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles, California, 90095.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Quigley H. A.; Broman A. T. The Number of People with Glaucoma Worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwitz J. H.; Glynn R. J.; Monane M.; Everitt D. E.; Gilden D.; Smith N.; Avorn J. Treatment for Glaucoma: Adherence by the Elderly. Am. J. Public Health 1993, 83, 711–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castleberry S.; Wang M.; Hammond P. T. Nanolayered siRNA Dressing for Sustained Localized Knockdown. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 5251–5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X.; Kim B.-S.; Kim S. R.; Hammond P. T.; Irvine D. J. Layer-by-Layer-Assembled Multilayer Films for Transcutaneous Drug and Vaccine Delivery. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 3719–3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso F.; Trau D.; Möhwald H.; Renneberg R. Enzyme Encapsulation in Layer-by-Layer Engineered Polymer Multilayer Capsules. Langmuir 2000, 16, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar]

- Moga K. A.; Bickford L. R.; Geil R. D.; Dunn S. S.; Pandya A. A.; Wang Y.; Fain J. H.; Archuleta C. F.; O’Neill A. T.; Desimone J. M. Rapidly-Dissolvable Microneedle Patches via a Highly Scalable and Reproducible Soft Lithography Approach. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 5060–5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciolino J. B.; Hoare T. R.; Iwata N. G.; Behlau I.; Dohlman C. H.; Langer R.; Kohane D. S. A Drug-Eluting Contact Lens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2009, 50, 3346–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram J. P.; Saluja S. S.; McKain J.; Lavik E. B. Sustained Delivery of Timolol Maleate from Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)/Poly(lactic acid) Microspheres for over 3 Months. J. Microencapsul. 2009, 26, 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratani H.; Fujiwara A.; Tamiya Y.; Mizutani Y.; Alvarez-Lorenzo C. Ocular Release of Timolol from Molecularly Imprinted Soft Contact Lenses. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 1293–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavik E.; Kuehn M. H.; Kwon Y. H. Novel Drug Delivery Systems for Glaucoma. Eye (London, U.K.) 2011, 25, 578–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Tyagi P.; Kadam R. S.; Holden C. A.; Kompella U. B. Hybrid Dendrimer hydrogel/PLGA Nanoparticle Platform Sustains Drug Delivery for One Week and Antiglaucoma Effects for Four Days Following One-Time Topical Administration. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7595–7606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.-Y.; Shih J.; Lo R.; Saati S.; Agrawal R.; Humayun M. S.; Tai Y.-C.; Meng E. An Electrochemical Intraocular Drug Delivery Device. Sens. Actuators, A 2008, 143, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Jones L.; Gu F. X. Nanomaterials for Ocular Drug Delivery. Macromol. Biosci. 2012, 12, 608–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppas N. A.; Hilt J. Z.; Khademhosseini A.; Langer R. Hydrogels in Biology and Medicine: From Molecular Principles to Bionanotechnology. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Aimetti A. A.; Machen A. J.; Anseth K. S. Poly(ethylene glycol) Hydrogels Formed by Thiol-Ene Photopolymerization for Enzyme-Responsive Protein Delivery. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6048–6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; Kim J.; Cezar C. A.; Huebsch N.; Lee K.; Bouhadir K.; Mooney D. J. Active Scaffolds for on-Demand Drug and Cell Delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 108, 67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H. J.; Chauhan A. Temperature Sensitive Contact Lenses for Triggered Ophthalmic Drug Delivery. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 2289–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocadlo D. J.; Davies G. J.; Laine R.; Withers S. G. Catalysis by Hen Egg-White Lysozyme Proceeds via a Covalent Intermediate. Nature 2001, 412, 835–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H.; Chu H.; Edalat F.; Cha J. M.; Sant S.; Kashyap A.; Ahari A. F.; Kwon C. H.; Nichol J. W.; Manoucheri S.; et al. Development of Functional Biomaterials with Micro- and Nanoscale Technologies for Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery Applications. J. Tissue Eng. Regener. Med. 2014, 8, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensign L. M.; Tang B. C.; Wang Y.-Y.; Tse T. A.; Hoen T.; Cone R.; Hanes J. Mucus-Penetrating Nanoparticles for Vaginal Drug Delivery Protect against Herpes Simplex Virus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 138ra79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrkach J.; Von Hoff D.; Mukkaram Ali M.; Andrianova E.; Auer J.; Campbell T.; De Witt D.; Figa M.; Figueiredo M.; Horhota A.; et al. Preclinical Development and Clinical Translation of a PSMA-Targeted Docetaxel Nanoparticle with a Differentiated Pharmacological Profile. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 128ra39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam K. R.; Walsh L. A.; Bock S. M.; Koval M.; Fischer K. E.; Ross R. F.; Desai T. A. Nanostructure-Mediated Transport of Biologics across Epithelial Tissue: Enhancing Permeability via Nanotopography. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow E. K.; Ho D. Cancer Nanomedicine: From Drug Delivery to Imaging. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 216rv4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Kim B. Y. S.; Rutka J. T.; Chan W. C. W. Advances and Challenges of Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2007, 4, 621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farokhzad O. C.; Langer R. Impact of Nanotechnology on Drug Delivery. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhorukov G. B.; Rogach A. L.; Zebli B.; Liedl T.; Skirtach A. G.; Köhler K.; Antipov A. A.; Gaponik N.; Susha A. S.; Winterhalter M.; et al. Nanoengineered Polymer Capsules: Tools for Detection, Controlled Delivery, and Site-Specific Manipulation. Small 2005, 1, 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin J. M.; Leonard A. D.; Pham T. T.; Sano D.; Marcano D. C.; Yan S.; Fiorentino S.; Milas Z. L.; Kosynkin D. V.; Price B. K.; et al. Effective Drug Delivery, in Vitro and in Vivo, by Carbon-Based Nanovectors Noncovalently Loaded with Unmodified Paclitaxel. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4621–4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diebold Y.; Calonge M. Applications of Nanoparticles in Ophthalmology. Prog. Retinal Eye Res. 2010, 29, 596–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Mochalin V. N.; Neitzel I.; Hazeli K.; Niu J.; Kontsos A.; Zhou J. G.; Lelkes P. I.; Gogotsi Y. Mechanical Properties and Biomineralization of Multifunctional Nanodiamond-PLLA Composites for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5067–5075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M.; Betz P.; Sun Y.; Gorb S. N.; Lindhorst T. K.; Krueger A. Saccharide-Modified Nanodiamond Conjugates for the Efficient Detection and Removal of Pathogenic Bacteria. Chemistry 2012, 18, 6485–6492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow E. K.; Zhang X.-Q.; Chen M.; Lam R.; Robinson E.; Huang H.; Schaffer D.; Osawa E.; Goga A.; Ho D. Nanodiamond Therapeutic Delivery Agents Mediate Enhanced Chemoresistant Tumor Treatment. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 73ra21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.-J.; Tzeng Y.-K.; Chang W.-W.; Cheng C.-A.; Kuo Y.; Chien C.-H.; Chang H.-C.; Yu J. Tracking the Engraftment and Regenerative Capabilities of Transplanted Lung Stem Cells Using Fluorescent Nanodiamonds. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 682–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore L.; Chow E. K.-H.; Osawa E.; Bishop J. M.; Ho D. Diamond-Lipid Hybrids Enhance Chemotherapeutic Tolerance and Mediate Tumor Regression. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 3532–3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O̅sawa E.; Ho D.; Huang H.; Korobov M. V.; Rozhkova N. N. Consequences of Strong and Diverse Electrostatic Potential Fields on the Surface of Detonation Nanodiamond Particles. Diamond Relat. Mater. 2009, 18, 904–909. [Google Scholar]

- Manus L. M.; Mastarone D. J.; Waters E. A.; Zhang X. Q.; Schultz-Sikma E. A.; Macrenaris K. W.; Ho D.; Meade T. J. Gd(III)-Nanodiamond Conjugates for MRI Contrast Enhancement. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 484–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Hu W.; Li J.; Tao L.; Wei Y. A Comparative Study of Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene Oxide, and Nanodiamond. Toxicol. Res. (Cambridge, U.K.) 2012, 1, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki J.; Yudasaka M.; Azami T.; Kubo Y.; Iijima S. Toxicity of Single-Walled Carbon Nanohorns. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 213–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam R.; Chen M.; Pierstorff E.; Huang H.; Osawa E.; Ho D. Nanodiamond-Embedded Microfilm Devices for Localized Chemotherapeutic Elution. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 2095–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Mochalin V. N.; Neitzel I.; Knoke I. Y.; Han J.; Klug C. A.; Zhou J. G.; Lelkes P. I.; Gogotsi Y. Fluorescent PLLA-Nanodiamond Composites for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochalin V. N.; Shenderova O.; Ho D.; Gogotsi Y. The Properties and Applications of Nanodiamonds. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang P. K.; Loh K. P.; Wohland T.; Nesladek M.; Van Hove E. Supported Lipid Bilayer on Nanocrystalline Diamond: Dual Optical and Field-Effect Sensor for Membrane Disruption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L.; O̅sawa E.; Barnard A. Confirmation of the Electrostatic Self-Assembly of Nanodiamonds. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 958–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett Q.; Laycock B.; Garrett R. W.. Hydrogel Lens Monomer Constituents Modulate Protein Sorption. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2000, 41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.-C.; Huang C.-L. Preparation of Clear Colloidal Solutions of Detonation Nanodiamond in Organic Solvents. Colloids Surf., A 2010, 353, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ren D.; Yi H.; Wang W.; Ma X. The Enzymatic Degradation and Swelling Properties of Chitosan Matrices with Different Degrees of N-Acetylation. Carbohydr. Res. 2005, 340, 2403–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H. J.; Chauhan A. Extended Release of Timolol from Nanoparticle-Loaded Fornix Insert for Glaucoma Therapy. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C.-C.; Burke M. T.; Carbia B. E.; Plummer C.; Chauhan A. Extended Drug Delivery by Contact Lenses for Glaucoma Therapy. J. Controlled Release 2012, 162, 152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccà S. C.; La Maestra S.; Micale R. T.; Larghero P.; Travaini G.; Baluce B.; Izzotti A. Ability of Dorzolamide Hydrochloride and Timolol Maleate to Target Mitochondria in Glaucoma Therapy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 129, 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.