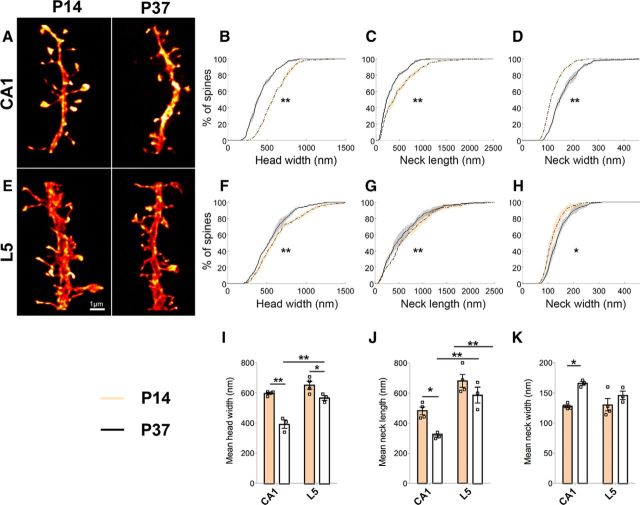

Figure 1.

During development, spine heads become smaller and spine necks become shorter and wider. A, E, Dendritic segments from CA1 (A) and L5 pyramidal cells (E) examined at P14 and P37. B–D, F–H, Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests of the cumulative frequency distributions show that for both CA1 (B–D) and L5 pyramidal cells (F–H), the distribution profiles of spine head widths (p < 0.001 for CA1; p < 0.02 for L5), neck lengths (p < 0.01) and neck widths (p < 0.001) significantly differ between the two ages. Here, whether the P value is considered significant or not is corrected for using the false discovery rate method, which controls false positives during multiple comparisons. Using two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparisons, mean differences in these parameters also show age and brain region-specific differences in the magnitude of the effects. I, For head width, age effect: F(1,10) = 49.94, p < 0.0001; region effect: F(1,10) = 31.16, p = 0.0002; age × region interaction: F(1,10) = 8.79, p = 0.01. J, For neck length, age effect: F(1,10) = 12.25, p = 0.006; region effect: F(1,10) = 40.14, p < 0.0001. K, For neck width, age-specific effect (F(1,10) = 14.61, p = 0.003) only in CA1 (p ≤ 0.01). Shaded areas around lines show interanimal variability. In bar graphs, data are represented as mean ± SEM, where n = number of animals. Scale bar, 1 μm. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.