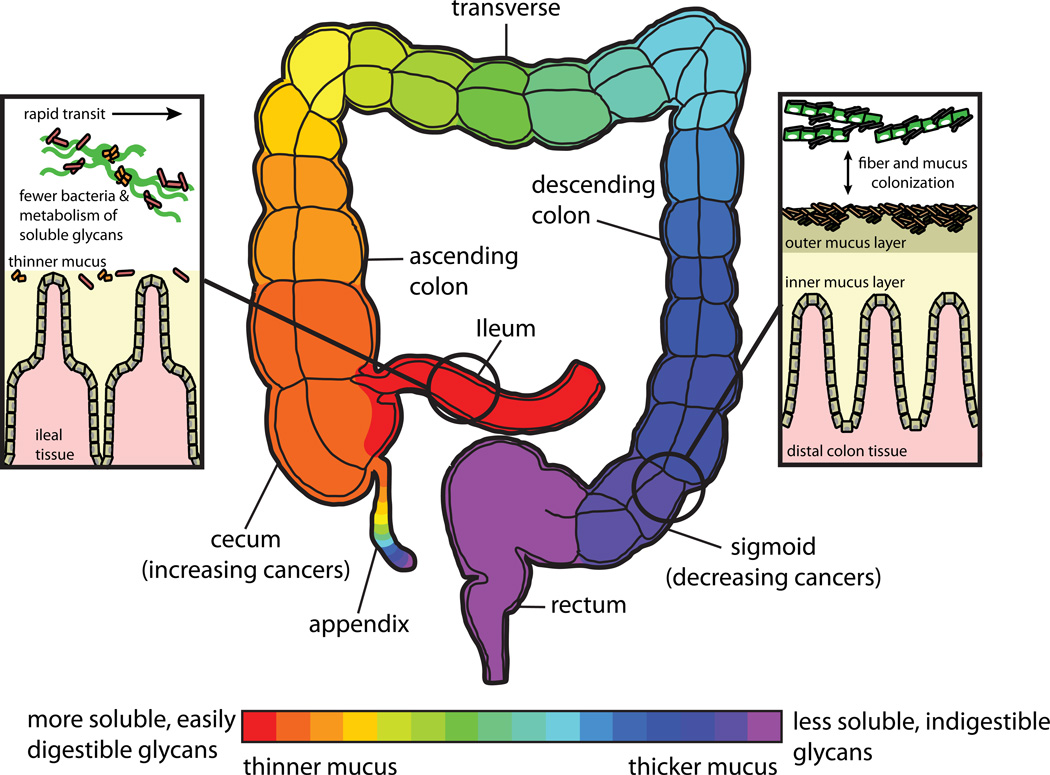

Fig. 3. Glycan utilization along the length of the gut and its potential health effects.

A schematic of the human ileum and colon that is color-coded to reflect potential glycan gradients (schematized according to the color bar at the bottom). The solubility and digestibility of dietary glycans that transit the lumen are variable and therefore each glycan is likely digested at a different rate. The thickness of intestinal mucus also follows a longitudinal gradient along the gut, but may be reciprocal to that of glycan digestibility, with greatest thickness present in the sigmoid colon and rectum where mostly insoluble/indigestible glycans are likely to be present121. The insets on the left and the right show schematics of the luminal and mucosal niches in the ileum and distal (sigmoid) colon. In the ileum, the mucus layer is relatively thin, transit time of contents is more rapid and bacteria are likely to target more soluble and rapidly digestible glycans, such as inulin and different oligosaccharide side-chains, such as α-arabinans and β-galactans, that are commonly attached to pectin (rhamnogalacturonan) backbones. In contrast, the distal colon has a much thicker mucus layer, transit time is slower and the residual glycans that fuel bacterial growth are likely to be less soluble and therefore take longer to degrade. Note the presence of inner and outer mucus layers, with bacterial colonization largely present in just the outer layer122. A possible reason for the increased mucus thickness in the distal gut may be to shield the epithelium from the more prolonged exposure to larger numbers of bacteria, which have more time to proliferate given the slower transit rate. It is widely accepted that increased dietary fibre intake is beneficial for colon health. In light of this idea, it is interesting that the incidence of colon cancers in several developed countries in North America, Europe and Asia are showing decreased abundance in the distal colon, and are increasing in more proximal regions over the last several decades123–126. One explanation offered for this phenomenon involves changing dietary habits in these societies, specifically reduced fiber intake and increased consumption of fat and animal protein. This trend could alter the microbiota or its metabolism in more distal regions, leading to carcinogenesis by several possible mechanisms (reduced transit time, increased production of toxic metabolites, or decreased production of protective metabolites like butyrate).