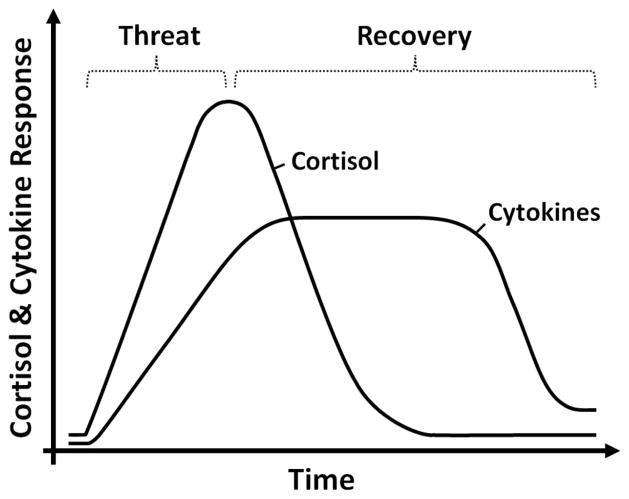

Figure 2.

Cortisol and proinflammatory cytokine responses to social cues indicating possible danger. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and inflammatory system coordinate to keep an individual physically safe and biologically healthy. Increases in HPA axis activity and the associated release of cortisol prepare an individual for “fight-or-flight” when he or she is exposed to cues indicating the presence of socially threatening conspecifics. This initial cortisol response has a strong anti-inflammatory effect, which allows the organism to react to the impending threat without being hampered by the onset of sickness behaviors, such as fatigue and social-behavioral withdrawal. As cues of the social threat wane, the body up-regulates the inflammatory response to accelerate wound healing and limit infection caused by possible injury. Glucocorticoid resistance allows for elevations in systemic inflammation to occur together with, or closely after, increases in cortisol. Although these dynamics are adaptive during actual, intermittent physical threat, prolonged activation of the HPA axis and inflammatory response caused by persistent actual or perceived threat is biologically costly and can increase a person’s risk for several inflammation-related conditions including asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, metabolic syndrome, and (possibly) certain cancers.