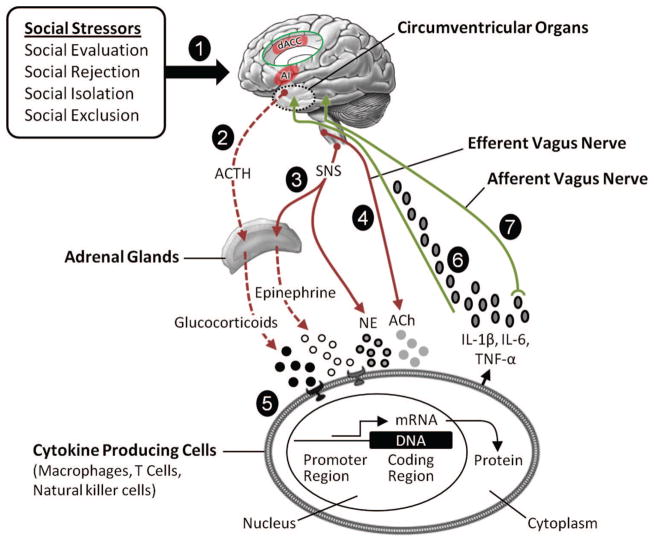

Figure 4.

Social signal transduction theory of depression. Social signal transduction theory of depression describes mechanisms that convert, or transduce, experiences of the external social environment into the internal biological environment of depression pathogenesis. (1) Social-environmental experiences indicating possible social threat or adversity (e.g., social evaluation, rejection, isolation, or exclusion) are represented neurally, especially in brain systems that process experiences of social and physical pain. Key nodes in this neural network include the anterior insula (AI) and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC, shown in the insert). These regions project to lower level brain areas (e.g., hypothalamus, brainstem autonomic control nuclei) that have the ability to initiate and modulate inflammatory activity via three pathways that involve (2) the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, (3) sympathetic nervous system (SNS), and (4) efferent vagus nerve. (5) Activation of these pathways leads to the production of glucocorticoids, epinephrine, norepinephrine (NE), and acetylcholine (ACh), which interact with receptors on cytokine-producing cells. Whereas glucocorticoids and acetylcholine have anti-inflammatory effects, epinephrine and norepinephrine activate intracellular transcription factors (e.g., nuclear factor-κB and activator protein 1) that bind to cis-regulatory DNA sequences to up-regulate inflammatory gene expression. When this occurs and immune response genes are expressed, DNA is transcribed into RNA and then translated into protein. The resulting change in cell function leads to the production of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin-1β [IL-1β], interleukin-6 [IL-6], tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α]) that signal the brain to induce cognitive, emotional, and behavioral alterations that include several hallmark symptoms of depression (e.g., sad mood, anhedonia, fatigue, psychomotor retardation, altered appetite and sleep, and social-behavioral withdrawal). Cytokines can exert these effects on the central nervous system by (6) passing through leaky or incomplete regions of the blood–brain barrier (e.g., circumventricular organs, organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis) and by (7) stimulating primary afferent nerve fibers in the vagus nerve, which relays information to brain systems that regulate mood, motor activity, motivation, sensitivity to social threat, and arousal. Although these neurocognitive and behavioral responses are adaptive during times of actual threat, as depicted in Figure 1, these social signal transduction pathways can also be initiated by purely symbolic, anticipated, or imagined threats—that is, situations that have not yet happened or that may never actually occur. Moreover, activation of these pathways can become self-promoting over time due to neuro-inflammatory sensitization and, as a result, remain engaged long after an actual threat has passed (see Figure 3). In such instances, these dynamics can increase risk for depression in the short-term and possibly promote physical disease, accelerate biological aging, and hasten mortality over the long run. ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; mRNA = messenger ribonucleic acid.