Abstract

Background: When a parent is terminally ill, one of the major challenges facing families is informing children of the parent's condition and prognosis. This study describes four ways in which parents disclose information about a parent's life-threatening illness to their adolescent children.

Methods: We audio-recorded and transcribed 61 individual interviews with hospice patients who were recruited from a large hospice in northeastern Ohio, their spouses/partners, and their adolescent children. The interviews were coded and analyzed using a constant comparison approach.

Results and Conclusions: Families inform adolescents about the progression of a parent's terminal illness in characteristic ways that remain fairly consistent throughout the illness, and are aimed at easing the adolescents' burden and distress. The families engaged in the process of disclosure in one of four ways: measured telling, skirted telling, matter-of-fact telling, and inconsistent telling. These results will inform the development of interventions that assist families with disclosure and are tailored to each family's communication style.

Introduction

About 2.5 million (3.5%) children in the United States will experience the death of a parent before they reach the age of 18.1 The final phase of a parent's illness is exceptionally stressful for adolescents who are at risk for adverse psychological reactions such as anger, despair, and social isolation.2,3 Bereaved youth experience higher rates of mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder than normal population controls.4–7 Although adolescents experience the greatest distress prior to the parent's death,8–11 depression may occur for up to two years later.4,7

The high levels of distress experienced by adolescents during a parent's illness and adverse consequences following a parent's death make it important to identify family processes that contribute to the adolescents' adjustment. Levels of distress (anxiety and depression) have been highly correlated with children's and adolescents' perceptions of the surviving parent's level of openness in general communication. Raveis and Siegel12 found that the parent's ability to establish open communication with bereaved children and adolescents clearly influenced their ability to successfully adjust to the loss. Lower rates of depression and anxiety are associated with open communication with the surviving parent with boys reporting lower levels of depression than girls, and older children reporting less anxiety than younger children. Considerable clinical data and experience also support the finding that healthy adaptation to parental loss is more likely to occur when family relationships are characterized by sharing information and the open expression of anger, guilt, sadness, and feelings about the deceased.13–15

Informing the children of a parent's condition and prognosis is one of the major challenges that families face.16 Although much research has been conducted on how health care providers tell patients that they have life-threatening diagnoses and poor prognoses,17,18 little is known about how parents tell their children that one parent is seriously ill or dying. More research is needed in order to understand how families carry out this difficult task.16,19

Several qualitative studies have examined how children are told that a parent has cancer. One study revealed that most mothers disclosed their diagnosis after it was confirmed by biopsy, although some waited until after surgery, and some did not disclose the diagnosis at all. Many mothers in this study indicated that they would have welcomed help from health professionals in talking to their children about their cancer.20 Adolescents remember how they were told about their parent's illness21 and report that hearing about a parent's diagnosis was a serious and threatening event in their lives. Although few could remember the words used to share the information, all recalled that they were worried their parent might die.2,22,23. The most significant information they recalled was that their mothers might survive.24

Some research has examined the effects of disclosure of parental illness on child functioning. Experts have traditionally argued that if the illness of a parent is not disclosed, children will experience high levels of anxiety because they are aware that something is wrong but do not have the opportunity to discuss their feelings.25,26 The association between disclosure and child functioning, however, is complex. For example, children over the age of 11 who were given partial information about the parent's diagnosis of multiple sclerosis had more emotional distress than those children who were given explicit information or no information at all.26 In a five year study of 310 parents living with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and their adolescent children, knowledge of parental serostatus was associated with more problem behaviors at recruitment. Problem behaviors, however, decreased over time among adolescents who were aware of their parent's serostatus and increased among those who were not aware.27 Murphy's25 review of disclosure to children by HIV-infected mothers confirmed that disclosure was often followed by psychological distress, but that most children adjusted over time. The reviewer speculated that children's enduring distress may be related to poorly handled disclosures (e.g., the disclosure was not planned or the mother was overly emotional).

Whereas most studies on disclosure have addressed a parent's chronic illness, four have focused on the disclosure of the imminent death of a parent. Rosenheim and Reicher's28 seminal study revealed that anxiety was significantly lower among children who were informed about the parent's life-threatening cancer diagnosis than those who were not informed. MacPherson19 found that the spectrum of disclosure ranged from neither parent talking about the impending death to both parents actively preparing the children for the death. The well parent often followed the lead of the ill parent until the imminence of death necessitated disclosure. Buchwald and colleagues29 found that the ways in which adolescents were informed about the parent's prognosis ranged from saying nothing to saying the parent may die. The adolescents speculated that their parent might die no matter what prognostic information they were given. Siegel et al.10 also reported discontinuities in families' communication practices. Whereas almost all bereaved children in their study were informed about the parent's cancer diagnosis, a sizable proportion reported no advance disclosure of the parent's probable death. Further, families rated highly by children on general communication were sometimes rated lower on communication about the parent's illness and death indicating a need for guidance on this specific issue. When there was more than one child in the family, parents almost always disclosed to all of the children in the family in a similar way and time. They suggested that future research move beyond the question of whether disclosure occurs, and focus on the content, timing, source, and circumstances of the disclosure.

The current study was designed to explore the complex and dynamic ways in which disclosure occurs when a parent is in hospice in order to better understand how to assist parents with the difficult challenge of informing children that a parent is seriously ill and/or dying. These findings are based on data obtained in an ongoing study (Adolescent Strategies Study) that aims to generate an explanatory model of the social processes used by adolescents and their parents to help the adolescent in the final months of the ill parent's life.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at Kent State University approved the study. Families of adolescents with a parent in hospice were recruited from a large hospice in northeastern Ohio. Adults in the hospice program were eligible to participate if they had children between the ages of 12 and 18, were able to speak, write, and understand English, and had the cognitive ability and physical stamina to complete an interview.

Research staff met regularly with the hospice staff prior to interdisciplinary team meetings to discuss the study, answer questions, and elicit help in recruiting participants who met study criteria. Contact information of potential participants was given to the research associate who called to screen potential participants and schedule the interviews with the ill parent, well parent, and adolescents.

Individual interviews were conducted in the participants' homes or in a private room at the hospice facility between December 2010 and July 2012. Interviews and field notes were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each transcript was reviewed for accuracy by the interviewer. Data were managed with the aid of the computer software program NVivo9 (QSR International Pty. Ltd., Doncaster, Australia). Each individual participant was given a $35.00 honorarium.

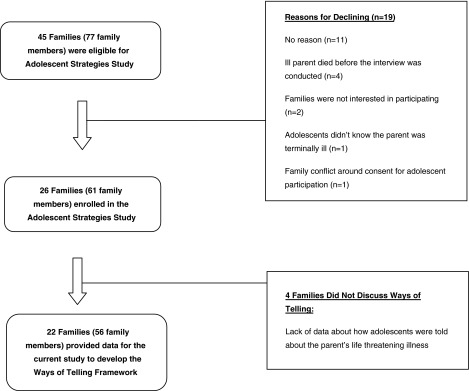

Forty-five families met inclusion criteria, and 26 participated in the Adolescent Strategies Study. Most of the families that declined to participate did not give a reason. Although the ill parents in 11 of the participating families were too ill to complete an interview, the spouse and/or adolescent participated. Parent surrogates, including grandparents or significant others acting in a parenting role, were included in the study. For the study reported here, 22 of the 26 participating families provided data that contributed to the Ways of Telling Framework described below. Figure 1 displays the number of families and family members who were eligible for the Adolescent Strategies Study, the number of families and family members who participated in the Adolescent Strategies Study, and the number of families and family members who contributed data to the study reported here. The participant characteristics of the last group are described in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Study participants.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics of Families That Contributed Data to the Ways of Telling Framework (n=56)

| Adolescents N=26 | Ill parent N=10 | Well parent N=20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 10 (38.5%) | 6 (60%) | 4 (%) |

| Female | 16 (61.5%) | 4 (40%) | 16 (%) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean | 15 | 55 | 50 |

| Range | 12–18 | 40–62 | 34–60 |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| Catholic | 8 (31%) | ||

| Protestant | 5 (19%) | ||

| Jehovah's Witness | 1 ( 4%) | ||

| None | 5 (19%) | ||

| No response | 7 (27%) | ||

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 20 (77%) | ||

| African American | 4 (15%) | ||

| Mixed race | 1 ( 4%) | ||

| No response | 1 ( 4%) | ||

| Current family annual income (n=22) | |||

| Under $10,000 | 5 (23%) | ||

| $10,001-$30,000 | 5 (23%) | ||

| $30,001- $50,000 | 3 (13%) | ||

| Over $50,001 | 7 (32%) | ||

| No response | 2 (9%) | ||

| Diagnosis (n=22) | |||

| Cancer | 17 (77%) | ||

| ALS | 1 (5%) | ||

| MS | 1 (5%) | ||

| Pulmonary disease | 1 (5%) | ||

| Mad cow | 1 (5%) | ||

| No response | 1 (5%) | ||

| Time from Interview to parent's death (days) | |||

| Mean | 41 | ||

| Range | 0–183 | ||

Note: The ill parent in four families died within one week of the interview. One parent died during the adolescent's interview.

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Analysis

Most participants spontaneously shared stories of incidents in which parents informed the adolescents of the ill parent's impending death. After analyzing the first few transcripts, the team noted that disclosure was a salient shared problem and decided that an in-depth analysis of this topic was warranted. Subsequent participants were asked to describe specific incidents in which adolescents were told that their parent was seriously ill or dying. All data in the transcripts related to disclosure were highlighted, extracted, and analyzed using constant comparison methods30,31 in order to describe common processes for telling adolescents of the illness or impending death of a parent.

Several procedures were used to enhance the trustworthiness of the findings. The perspectives of the parents and adolescents were obtained. The analysis was conducted by a interdisciplinary research team that included nursing and social work. Peer debriefing and discussion of emerging findings occurred at weekly team meetings. All methodological and analytic decisions were documented in an audit trail.

Results

The descriptions of the disclosures by the ill parent, well parent, and adolescent(s) were generally consistent. The families had characteristic ways of disclosing that did not vary significantly across time. For example, parents tended to disclose the imminence of the death in the same way they had disclosed the initial diagnosis of the illness. The families differed considerably, however, in how they handled disclosures to the adolescents, and their disclosures often reflected how they interacted or communicated before the illness.

We concluded, therefore, that families inform adolescents about the progression of a parent's life-threatening illness in characteristic ways that remain fairly consistent throughout the illness. When asked how she shared information about her husband's illness with her adolescent children, one mother stated, “[You should] keep the lines communication open and be honest. But that starts very young, it doesn't just happen when somebody gets sick, you gotta live like that first because a lot of families keep secrets.” The framework we developed to describe the processes of disclosure of a parent's illness/imminent death to adolescents includes four different ways of telling. We argue that all four ways are based on the shared purpose of making the disclosure “easier to swallow” for the adolescents.

Making it “easier to swallow”

All the families attempted to tell the adolescents about the parent's serious illness and imminent death in ways that spared them worry, burden, or emotional distress. When delivering “bad news,” the parents tried to “soften the blow” with assurances that the parent was going to heaven, affirmations of the parents' love for the adolescent, guarantees that the family would be “okay,” and proclamations that the well parent would “be there” for the adolescent. The parents tried to comfort the adolescents or assuage their concerns. For example, one father told his adolescent daughter, “You know, we love you, but I am sick again.” We used one family's phrase, “making it easier to swallow,” to label the overarching goal of the families in disclosing the parent's illness.

The families engaged in the process of “making it easier to swallow” in one of four ways: measured telling, skirted telling, matter-of-fact telling, and inconsistent telling. How the families disclosed, the interactions that comprised disclosures, the strategies used by the parents and the adolescents during disclosures, and the outcomes of the disclosures are described for each of the four ways of telling and are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ways of Telling Adolescents That a Parent Is Seriously Ill or Dying

| Ways of telling | Interactions | Strategies | Participant quotes | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skirted telling:Beating around the bush | Complicit | Parents | Generally positive | |

| Talking about the death in generalities | “We are all going to die.” | |||

| Hinting that something was seriously wrong with the ill parent but not stating it directly | “I haven't told her. I say something leaning toward it [in case] he doesn't make it.” | |||

| Providing ambiguous information to allow the adolescents to interpret it as they wished | “I let her detect whatever she wants without spilling the beans.” | |||

| Going along with the adolescents when they denied the reality of the imminent death | “She plans her wedding around me.” | |||

| Providing limited information | “She knows it is pulmonary, it's breathing, I haven't told her [it's cancer].” | |||

| Talking about the death as a possibility rather than an eventuality | “If I die, when I die …” | |||

| Waiting for the adolescents to bring up the illness | “I figure when she is ready to talk about it she will talk about it.” | |||

| Allowing the adolescents to avoid talking about the illness or imminent death | “If she doesn't want to talk to me about it, I am not going to bug her, I am not going to press her …” | |||

| Adolescents | ||||

| Circumventing discussion of the illness or impending death | “I try to avoid the situation.” | |||

| Informing the parents they did not want to discuss the illness | “I just don't want to talk about it.” | |||

| Acting as if the parent was not dying | “Mom is not going nowhere …” | |||

| Measure telling:Being kept in the loop | Transactional | Parents | Positive | |

| Taking time to absorb information before sharing it with the adolescent | “When we get information we would digest it and then decide how much of this do they need to know.” | |||

| Preparing for the disclosures | “I kept running scenarios through in my mind of conversations and how I am going to say things.” | |||

| Making reasoned choices about what information to tell | “You don't have to tell them every dirty detail or every horrible thing that is happening, but it is their right to know the guts of it.” | |||

| Discussing plans for disclosure with a spouse | “We were both sitting there saying how are we going to do this one, how are we going to tell them this one …” | |||

| Embracing the adolescents “right” to know | “You have every right to know.” | |||

| Giving information to the adolescents gradually | “I didn't try to explain it any further than that, I just let it sink in.” | |||

| Adolescents | ||||

| Considering what information they wanted or needed | “They [siblings] talk together and try to puzzle it out and decide we need to go to the top [parents] on this one.” | |||

| Proactively letting their parents know what information they were ready to hear | “They will bring things up when they are ready to hear …” | |||

| Indicating that they could endure bad news | “Both [adolescents] were matter-of-fact…I can see they are handling it.” | |||

| Returning to their parents with questions after a disclosure | “She started talking about this stupid band and she went back to it a little bit later.” | |||

| Matter-of-fact telling:Having a conversation | Instructive | Parents | Neutral | |

| Laying out the realities of the parent's illness | “[I wanted] to make sure everyone knows what is going on.” | |||

| Discussing the future practical implications of the illness/impending death | “You've got to learn to save your money.” | |||

| Presenting decisions that needed to be made | “What do you think about me being cremated and donating my body parts?” | |||

| Adolescents | ||||

| Revealing to parents that they understand the realities of the illness | “He's sick, he's in bad shape, he goes to bed, he watches TV.” | |||

| Inconsistent telling: Not knowing what is going on | Conflictual | Parents | Negative | |

| Giving mixed-messages | “I tell them he has three or four weeks left but I don't tell them he is dying.” | |||

| Telling the adolescents they did not have information when they did | “We don't know anything.” | |||

| Giving information that differed from that provided by other family members | “My brother, I think, said 4 weeks, and my mom told me 6 months.” | |||

| Vacillating between not telling any information and telling dire information “straight-out” | “He kind of hinted toward it in a joking fashion.” | |||

| Adolescents | ||||

| Accepting that the parent has a serious illness by not acknowledging the parent was dying | “We kind of had an idea that this was not something that was going to turn itself around …” |

Measured telling: Being kept in the loop

Seven families engaged in a type of disclosure that we labeled “measured telling.” Measured telling occurred when parent(s) told adolescent(s) about the serious illness or imminent death of the ill parent in a way that was thoughtfully considered. The term “measured” was chosen because the parents carefully and rationally determined the nature, the amount, and the timing of disclosures, taking into account the adolescent's age and emotional state. Although several participants espoused being “brutally honest,” in reality they disclosed information to their adolescents in a way that was methodical and restrained. For example, several had taken time to “digest” information they received from medical providers before sharing the information with the adolescents. The parents had discussed their disclosure plan with each other, other family members, and, in a few cases, health care professionals. A few parents had prayed about the disclosure beforehand. The adolescents felt well-informed but not overwhelmed. One adolescent said, “To be told and to feel like you weren't being left out even if you didn't completely understand what was going on, just to know you were still being informed about everything and being kept in the loop …”

The interactions between parents and adolescents in measured telling are best described as transactional. The parents continually assessed the adolescents' responses to information they were given and adapted their telling accordingly. The adolescents, in turn, communicated either directly or indirectly to their parents about how much information they wanted and how they wanted to receive it. Measured telling, therefore, involved continual adjustments by the parents based on the adolescents' communication of their needs.

The parents and the adolescents used a number of strategies for measured telling. The parents took time to absorb information before sharing it with the adolescent, prepared for the disclosures, made reasoned choices about what information to impart, discussed plans for disclosure with a spouse, embraced the adolescents “right” to know, and gave information to the adolescents gradually. The adolescents, in turn, considered what information they wanted or needed, proactively let their parents know what information they were ready to hear, indicated that they could endure bad news, and returned to their parents with questions after a disclosure.

The outcomes of measured telling were always positive. The parents were proud of how they had disclosed the illness/imminent death, and the adolescents were satisfied with how the disclosure occurred. Several participants stressed that measured telling engendered trust in the family. A few participants suggested that the way their families handled disclosure could serve as a model for other families in similar situations. The adolescents were gratified that their parents shared important information with them. One stated, “It was really nice to know that we knew everything, and they weren't holding anything back.”

Skirted telling: Beating around the bush

Six families engaged in a type of disclosure that we labeled “skirted telling.” Skirted telling occurred when parent(s) told the adolescent(s) about the illness/imminent death of the parent in a way that was indirect or ambiguous. The parents did not hide the truth or lie to the adolescents, but avoided revealing information “straight out.” The participants who used skirted telling talked about “letting it slip in,” “not spilling the beans,” “talking in general,” “saying some things here, saying some things there,” or “not sharing too much.” The term “skirted” was chosen because the families bypassed the more difficult information in order to make the disclosure easier for the adolescents. One ill father described how he and his wife told their adolescent daughter about his impending death: “We kind of beat around the bush. We told her I wasn't going to do chemo no more, that it wasn't working. We didn't tell her that the doctor told me that I had 6 to 8 months.”

The interactions between parents and adolescents in skirted telling are best described as complicit. The parents and the adolescents seemed to have an unspoken agreement that the parents should not share the most dire information. One well mother explained: “She [her adolescent daughter] doesn't want to hear it, and I don't want to be sharing too much with her.” The parents hesitated to tell “the whole truth,” and the adolescents let the parents know that they did not want to hear “the whole truth.” The parents and the adolescents were therefore “on the same page” about how disclosure should occur. One ill father described how all family members referred to trips they would take together the following spring, although it was unlikely that he would be alive. Referring to his adolescent daughter, he revealed, “I might be tricking her [his daughter] and she might be tricking me.”

The parents and the adolescents used a number of strategies for skirted telling. The parents talked about the death in generalities, hinted that something was seriously wrong with the ill parent but did not state it, provided ambiguous information to allow the adolescents to interpret it as they wished, “went along with” the adolescents when they denied the reality of the imminent death, provided limited information, talked about the death as a possibility rather than an eventuality, waited for the adolescents to bring up the illness, and allowed the adolescents to avoid talking about the illness or imminent death. The adolescents who engaged in skirted telling circumvented discussion of the illness or impending death, informed their parents they did not want to discuss the illness, and acted as if the parent was not dying.

The outcomes of skirted telling were generally positive. Because both the parents and the adolescents welcomed telling that was indirect or ambiguous, they did not experience discord in relation to disclosure. The parents felt they were allowing the adolescents to live as normally as possible, and the adolescents were content with the information they received. In one family, skirted telling resulted in an adolescent “being told everything” by a sibling. Most of the families, however, revealed no negative repercussions related to skirted telling.

Matter-of-fact telling: Having a conversation

Five families engaged in a type of disclosure we labeled as “matter-of-fact telling.” Matter-of-fact telling occurred when parent(s) told adolescent(s) about the serious illness or imminent death of the ill parent in a way that was factual and unemotional. These disclosures revealed news about the ill parent but focused mainly on practical issues, such as explaining the parent's symptoms, revealing parental needs, and making practical decisions about funeral arrangements, type of burial, and organ donation. These disclosures were described as everyday conversations, rather than as watershed incidents in which parents “broke bad news” to adolescents. One adolescent stated, “It was just like having a conversation.” The parents were attempting to make the illness “easier to swallow” for the adolescents by alerting them to how the illness would affect their lives in practical, realistic ways, rather than making the illness “easier to swallow” by attending to their grief. The term “matter-of-fact” was chosen because the disclosures were straightforward and informative rather than emotional. One adolescent daughter said, “We [the family] don't discuss it; it is a day-to-day thing.”

The interactions between parents and adolescents in matter-of-fact telling were best described as instructive. The parents provided information that the adolescents “needed to know,” and the adolescents received the information dispassionately. Neither the parents nor the adolescents vividly recalled the disclosure incidents because they were embedded in daily conversations.

The parents and the adolescents used a number of strategies for matter-of-fact telling. The parents laid out the realities of the parent's illness, discussed the future practical implications of the illness/impending death, and presented decisions that needed to be made. The adolescents, in turn, revealed to their parents that they understood the realities of the illness and engaged in decision making to the extent they were able.

The outcomes of matter-of-fact telling were neutral. The families did not view these disclosures as either positive or negative; the conversations simply occurred. The utilitarian focus of the disclosures in these families seems to be related to a number of factors. In one family, the adolescent evidenced a developmental delay that limited her understanding of the ill parent's prognosis (e.g., “I don't know whether she comprehends all this stuff.”). A disruption of the relationship between the ill parent and the adolescent due to family discord or the absence of the parent from the child's life accounted for an adolescent's lack of emotional attachment to the dying parent in some cases (e.g., “I don't think they really love him.”). Poverty and family stressors took precedence over emotional grief work related to the ill parent's death in other families.

Inconsistent telling: Not knowing what is going on

Four families engaged in a type of disclosure that we have labeled “inconsistent telling.” Inconsistent telling occurred when parent(s) told adolescent(s) about the serious illness or impending death of the ill parent in ways that were changing and unpredictable. Inconsistent telling involved a mixture of not telling (e.g., “I didn't feel he was ready to hear.”), telling very directly (e.g., “I was flat out there.”), telling practical information (e.g., “I told them there is an oxygen machine coming.”), delays in telling (e.g., “They told us we were looking at the longest 2 weeks, and I didn't say anything to [son] right away.”), and telling information that was not true (e.g., “I kept telling him we do not know what was going on with your dad.”). No consistent patterns of disclosure could be discerned for these families. These families were also the only ones in which family members gave different versions of telling incidents during the interviews. For example, one mother and father disagreed about who was present when the father's serious illness was first disclosed. The adolescents and parents often could not recount specific details of disclosure incidents. The term “inconsistent” was chosen because parents disclosed the serious illness or impending death of the ill parent in ways that were shifting and seemingly capricious.

The interactions between parents and adolescents in inconsistent telling are best described as conflicted. The parents often misjudged what the adolescents wanted or needed to know about the ill parent (e.g., “I didn't know what was going on in his head.”), and the adolescents were dissatisfied with what they were told (e.g., “They never filled me in.”). The adolescents were often angry at their parents for how they handled disclosure (e.g., “A couple of times he got angry at me for leaving him out of the loop.”), and the parents were frustrated that the adolescents did not respond to disclosures as the parents had anticipated. The disclosures were often spontaneous and therefore caught the adolescents off guard.

The parents and the adolescents used a number of strategies for inconsistent telling. The parents gave mixed messages, told the adolescents they did not have information when they did, provided information that differed from that given by other family members, and vacillated between not revealing any information and relating dire information “straight-out.” The adolescents accepted that the parent had a serious illness but often did not acknowledge that the parent was dying.

The outcomes of inconsistent telling were generally negative. Many adolescents expressed anger when they heard the “bad news” (e.g., “He kind of turns around disgusted.”), and a few sought information from other sources (e.g., “I asked the nurse how much time he had left.”). The adolescents felt that they had received too much or not enough information. Although the parents attempted to make the news “easier to swallow,” they were often unsuccessful. The parents were aware that the adolescents were dissatisfied with how they were told about the parent's illness/impending death, but did not plan for future disclosures. All four families were experiencing discord or adversity (e.g., marital conflict, drug abuse, mental illness) in addition to the parent's impending death. Thus, disclosures generally occurred in the context of family chaos and conflict.

Discussion

The findings reveal that families with a parent who is seriously ill tell their adolescent children about the parent's illness and imminent death in characteristic ways that vary among families. Although many of the participants lauded being “open and direct,” the adolescents were informed in more complex and nuanced ways. The ways in which adolescents were informed were more related to ongoing family dynamics and circumstances than to characteristics or the stage of the illness. Families that functioned well tended to use measured telling; families that were especially child-centered used skirted telling; families that were estranged from the ill person used matter-of-fact telling; families that were troubled used inconsistent telling. Measured telling seemed to be the “model” for a healthy way of telling. The families that used skirted or matter-of-fact telling, however, were generally satisfied with the way they disclosed as these ways of telling were acceptable to both the parents and adolescents and were congruent with family circumstances.

Our results resonate with findings from other studies. The process we describe as measured telling, for example, supports MacPherson's19 conclusion that parents need to understand information about a parent's impending death and come to terms with it before they can talk with their children. Our study augments studies that emphasized the various ways in which adolescents were informed of a parent's life-threatening illness.10,29 Our results also confirm studies that found that although adolescents may not remember the words used to inform them about their parent's illness, they recall that they sought to determine whether their parent was going to die.2,22–24 The process we describe as skirted telling is reminiscent of research on how health care providers often discuss death in veiled terms, rather than directly address end-of-life issues.17

Our results provide robust examples of four ways that parents disclose information about a parent's life-threatening illness to their adolescent children. These findings suggest that clinicians who work with families in which one parent is at the end of life need to appreciate the family's unique relationships and situations when discussing issues of disclosure. For example, common clinical wisdom suggests that adolescents need a chance to grieve the loss of a parent. Some of the adolescents in this study, however, did not have a close relationship with the parent who was dying; their concerns were more practical than emotional. Similarly, although the rational and thoughtful approach of the families who engaged in measured telling seemed exemplary, the use of skirted telling worked well for the families who were particularly invested in not disrupting the adolescents' lives as the illness progressed. At least some of the families in the sample clearly struggled with disclosing information to the adolescents. Families who disclosed in inconsistent ways experienced negative consequences, such as intense anger in the adolescents and inadvertent telling by others outside the family. Clinicians, therefore, should be aware that families who use inconsistent telling may need assistance with disclosing in ways that meet the needs of both the parents and the adolescents and helps the adolescent cope with the loss of the parent.

Our study had several limitations. The participants' descriptions of the telling incidents were retrospective, thereby introducing recall bias. This limitation was offset to some degree by having multiple family members describe the same incident. Second, generalizability was limited because our sample was drawn from only one hospice facility. Third, our sample size did not allow us to explore how family characteristics (e.g., religious affiliation, race, family income) influence the ways of telling. A larger sample with robust representation from differ demographic groups would permit such exploration. Our sample size also prohibits us from making any claims that the number of families who described each way of telling reflects such a distribution in the general population or that the ways of telling we have identified are exhaustive.

In conclusion, our findings highlight the importance of recognizing the potential challenges for parents as they talk with their adolescent children about the parent's life-threatening illness and imminent death. These results can be used to inform the development of interventions in which health care professionals assist families with disclosure by tailoring strategies according to the family's communication styles.

Future research should investigate changes in disclosures over time and outcomes related to adolescent bereavement. Psychological outcomes could also be related to specific behavioral problems and other indicators for poor coping. Prospective longitudinal studies that include having the parents and adolescents keep journals during specific periods would provide more contemporary data. Retrospective studies should explore the surviving parent's thoughts and feelings about disclosure style after the death of the patient. Teens with divorced parents who have differing communication styles may be another population of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research [R21 NR012700], Denice Sheehan, Principal Investigator. We are grateful to the staff, patients, and families of Hospice of the Western Reserve, Cleveland, Ohio and The Gathering Place, Beachwood, Ohio for their time and effort in making this study possible. Thanks to Barb Juknialis for her skill and expertise in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.US Bureau of the Census: Statistical abstracts of the United States: 2000. 111thed Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beale EA, Sivesind D, Bruera E: Parents dying of cancer and their children. Palliat Support Care 2004;2:387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson P, Rangganadhan A: Losing a parent to cancer: A preliminary investigation into the needs of adolescents and young adults. Palliat Support Care 2010;8:255–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent D, Melhem N, Donohoe MB, Walker M: The incidence and course of depression in bereaved youth 21 months after the loss of a parent to suicide, accident, or sudden natural death. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:786–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerel J, Fristad MA, Verducci J, Weller RA, Weller EB: Childhood bereavement: Psychopathology in the 2 years postparental death. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;45:681–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melhem NM, Walker M, Moritz G, Brent DA: Antecedents and sequelae of sudden parental death in offspring and surviving caregivers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:403–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray LB, Weller RA, Fristad M, Weller EB: Depression in children and adolescents two months after the death of a parent. J Affect Disord 2011;135:277–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saldinger A, Cain AC, Porterfield K: Traumatic stress in adolescents anticipating parental death. Prev Res 2005;12:17–20 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel K, Mesagno FP, Karus D, et al. : Psychosocial adjustment of children with a terminally ill parent. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992;31:327–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel K, Karus D, Raveis VH: Adjustment of children facing the death of a parent due to cancer. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35:442–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dehlin LRLM: Adolescents' experiences of a parent's serious illness and death. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raveis VH, Siegel K: Children's psychological distress following the death of a parent. J Youth Adolescence 1999;28:165 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaffman M, Elizur E, Gluckson L: Bereavement reactions in children: Therapeutic implications. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 1987;24:65–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Worden JW: Children and Grief: When a Parent Dies. NY: Guilford Press, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black D, Urbanowicz MA: Family intervention with bereaved children. Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Disciplines 1987;28:467–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seccareccia D, Warnick A: When a parent is dying: Helping parents explain death to their children. Can Fam Physician 2008;54:1693–1694 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson WG, Kools S, Lyndon A: Dancing around death: Hospitalist–patient communication about serious illness. Qual Health Res 2013;23:3–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul CL, Clinton-McHarg T, Sanson-Fisher R, Douglas H, Webb G: Are we there yet? The state of the evidence base for guidelines on breaking bad news to cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2960–2966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacPherson C: Telling children their ill parent is dying: A study of the factors influencing the well parent. Mortality 2005;10:113–126 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes J, Kroll L, Burke O, Lee J, Jones A, Stein A: Qualitative interview study of communication between parents and children about maternal breast cancer. BMJ 2000;321:479–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan DK, Draucker CB: Interaction patterns between parents with advanced cancer and their adolescent children. Psycho-oncol 2011;20:1108–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy VL, Lloyd-Williams M: How children cope when a parent has advanced cancer. Psycho-oncol 2009;18:886–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finch A, Gibson F: How do young people find out about their parent's cancer diagnosis: A phenomenological study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2009;13:213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristjanson LJ, Chalmers KI, Woodgate R: Information and support needs of adolescent children of women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004;31:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy DA: HIV-positive mothers' disclosure of their serostatus to their young children: A review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008;13:105–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paliokosta E, Diareme S, Kolaitis G, et al. : Breaking bad news: Communication around parental multiple sclerosis with children. Fam Syst Health 2009;27:64–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee MB, Rotheram-Borus M: Parents' disclosure of HIV to their children. AIDS 2002;16:2201–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenheim E, Reicher R: Informing children about a parent's terminal illness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1985;26:995–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchwald D, Delmar C, Schantz-Laursen B: How children handle life when their mother or father is seriously ill and dying. Scand J Caring Sci 2012;26:228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaser BG: Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley: Sociology Press, 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaser BG, Straus AL: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine, 1967 [Google Scholar]