Abstract

Mutations in the transcription factor Pdx1 cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young 4 (MODY4). Islet transduction with dominant negative Pdx1 (RIPDN79PDX1) impairs mitochondrial metabolism and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). Transcript profiling revealed suppression of nuclear encoded mitochondrial factor A (TFAM). Herein, we show that Pdx1 suppression in adult mice reduces islet TFAM expression coinciding with hyperglycaemia. We define TFAM as a direct target of Pdx1 both in rat INS1 cells and human islets. Adenoviral overexpression of TFAM along with RIPDN79PDX1 in isolated rat islets rescued mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number and restored respiratory chain activity as well as glucose-induced ATP synthesis and insulin secretion. CGP37157, which blocks the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, restored ATP generation and GSIS in RIPDN79PDX1 islets, thereby bypassing the transcriptional defect. Thus, the genetic control by the β-cell specific factor Pdx1 of the ubiquitous gene TFAM maintains β-cell mtDNA vital for ATP production and normal GSIS.

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria are the site of cellular energy provision and control not only vital functions but also specialized processes such as insulin secretion in the pancreatic β-cells (Maechler and C.B., 2001; Wiederkehr and Wollheim, 2008). Normal glucose homeostasis depends on the efficient adaptation of insulin secretion rates to the actual blood glucose concentration. The β-cell is poised to funnel glucose-derived metabolites to the mitochondria through its unique gene expression profile, permitting the generation of ATP and other factors coupling metabolism to insulin exocytosis (Gauthier et al., 2008; Jensen et al., 2008; Wiederkehr and Wollheim, 2006). The end product of glycolysis in the β-cell is pyruvate, which is transferred to the mitochondria leading to the generation of NADH and FADH2 (Ishihara et al., 1999). Oxidation of these reducing equivalents drives proton pumping of respiratory chain complexes, resulting in hyperpolarisation of the electrical potential and mitochondrial matrix alkalinization (Wiederkehr et al., 2009). These changes accelerate mitochondrial ATP synthesis, resulting in the closure of ATP-sensitive K+ channels at the plasma membrane causing depolarization and calcium influx (Hiriart and Aguilar-Bryan, 2008). The rise in cytosolic Ca2+, apart from triggering insulin exocytosis, is relayed to the mitochondrial matrix where the activity of dehydrogenases is stimulated thereby reinforcing the generation of metabolic coupling factors (Wiederkehr and Wollheim, 2008).

The respiratory chain function is critically dependent on both nuclear and mitochondrial gene transcription. In fact, 13 of the many polypeptide subunits of complex I, III, IV and V are encoded by the mtDNA whereas subunits of complex II (succinate dehydrogenase) are nuclear encoded. Mutations or deletions in the mitochondrial genome lead to a rare form of diabetes, maternally inherited diabetes (MID) (Maassen et al., 2005) illustrating the importance of mitochondria in β-cell function. Stability and transcriptional activity of mtDNA is predominantly controlled by a nuclear-encoded factor, mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) (Falkenberg et al., 2007; Scarpulla, 2008). The vital function of TFAM is illustrated by the lethal phenotype of the global TFAM ablation in the mouse. Organ-targeted depletion of TFAM has substantiated the importance of mitochondrial metabolism in various cell types, including cardiomyocytes and β-cells (Larsson and Rustin, 2001; Silva et al., 2000). Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction accelerates biological aging and a polymorphism in the tfam gene has been associated with familial Alzheimer’s disease (Belin et al., 2007). Conversely, mice overexpressing TFAM are protected from age-dependent impairment of brain performance by preserving mitochondrial function in microglia (Hayashi et al., 2008).

The pancreatic homeodomain transcription factor, Pdx1 is considered a β-cell master gene important for its embryonic development and differentiated function (Oliver-Krasinski and Stoffers, 2008; Servitja and Ferrer, 2004). Homozygous null mutations in the pdx1 gene result in pancreas agenesis whereas heterozygocity is associated with maturity onset diabetes of the young 4 (MODY4) (Oliver-Krasinski and Stoffers, 2008). A recent genome-wide linkage and admixture mapping of Type 2 diabetes includes Pdx1 as a candidate gene in Afro-American subjects (Elbein et al., 2009). Pdx1+/− mutant mice display impaired insulin secretion and late onset β-cell apoptosis (Brissova et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2003). Both defects were recapitulated using an in vitro rat islet model expressing a dominant negative variant of Pdx1 lacking the main transactivation domain (DN79PDX1) (Gauthier et al., 2004). The blunted glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) was linked to impaired mitochondrial function, a consequence of decreased transcription of mtDNA encoded enzyme subunits of the respiratory chain. Remarkably, TFAM transcript levels were markedly suppressed suggesting that Pdx1 may regulate transcription of mtDNA encoded genes via regulation of TFAM (Gauthier et al., 2004). Here, we tested whether TFAM expression and/or normalisation of mitochondrial calcium signals can restore mitochondrial function and metabolism-secretion coupling in Pdx1 loss-of-function islets.

RESULTS

TFAM expression is regulated by Pdx1 in vivo

To investigate whether TFAM is a target of Pdx1, studies were performed in a transgenic mouse model that allows the conditional doxycycline-dependent suppression of Pdx1 in adult animals (Holland et al., 2005; Holland et al., 2002). Doxycycline was administered to 6-month-old male mice for 14 consecutive days. This resulted in the expected massive reduction of Pdx1 expression (decreased by 90%) and marked increase in blood glucose secondary to β-cell dysfunction (Figure 1). The transcript level of the nuclear encoded gene TFAM was also reduced by 55%. As consequence, there was a suppression of ND1, a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) encoded subunit of respiratory chain complex I NADH DH (Figure 1B). These results recapitulate in an in vivo model our earlier observations in rat islets transduced with a dominant-negative variant of Pdx1 (Gauthier et al., 2004). TFAM transcript levels were also assessed in islets isolated from PDX1+/− mice (Brissova et al., 2002). Surprisingly, Pdx1 mRNA levels were only marginally decreased by 23±5 % relative to control littermates with a minute non-significant decrease in TFAM mRNA (10±4 %, n=5). Thus, it appears that Pdx1 expression levels in this model of heterozygous mice (Brissova et al., 2002) are higher than the expected 50 %, resulting in only minor changes in TFAM transcript.

Figure 1. Reduced TFAM expression and hyperglycemia ensue subsequent to doxycycline-mediated repression of Pdx1 in vivo.

A: Pdx1tTA/tTA; TgPdx1 transgenic mice bearing a conditionally doxycycline-repressed pdx1 transgene were given a single intraperitenal injection of doxycycline (100 mg/kg in final volume of 250 ul of water) followed by 14 days of treatment in the drinking water. Fasting blood glucose was measured daily using a Precision Xceed apparatus. B: Pdx1, TFAM and NADDH ND1 mRNA levels were then determined by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to the housekeeping gene, cyclophilin. Values are derived from three independent pairs of animals and are presented as fold repression as compared to control non-doxycycline treated mice. **P<0.01.

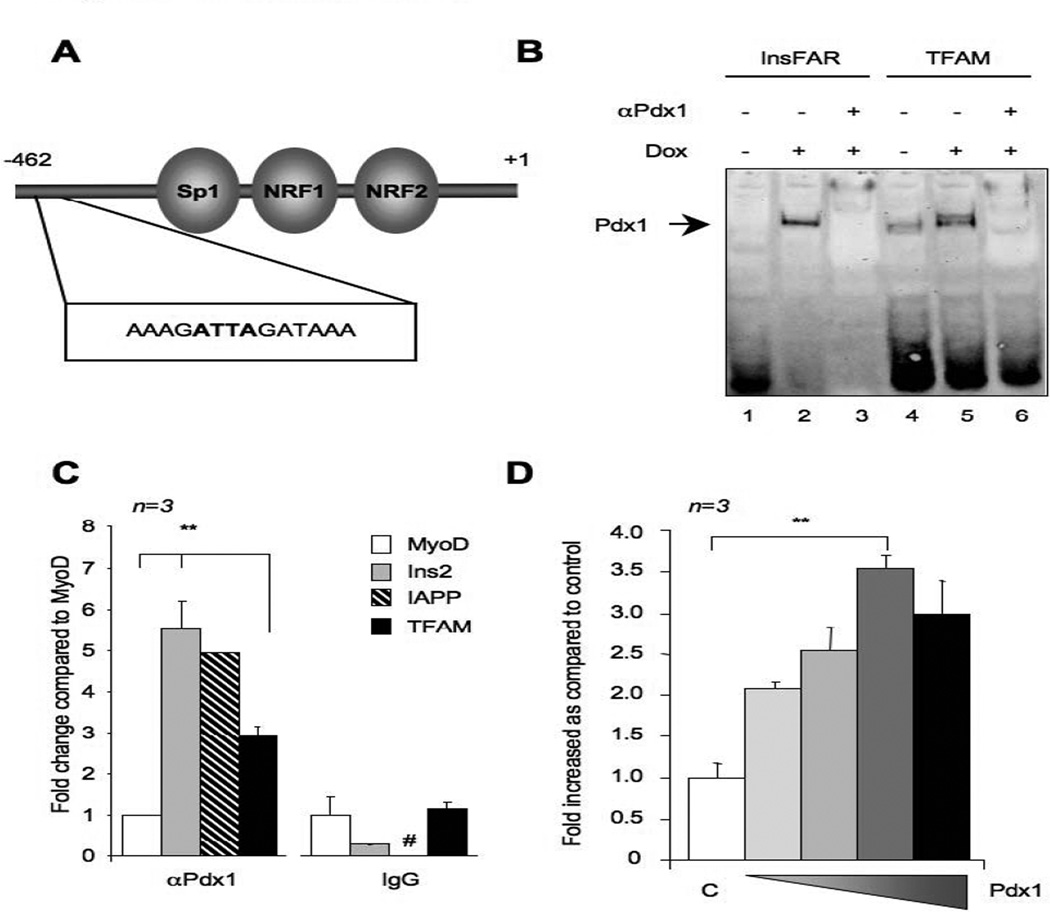

Pdx1 controls TFAM transcriptional activity

As our previous in vitro studies were performed with rat islets, we next performed an in silico scan of the rat tfam gene promoter for putative Pdx1 binding sites. A single homeobox consensus core sequence was identified at position -462 with respect to the transcriptional start site (Figure 2A). Using an INS-1 cell line permitting DOX inducible over expression of Pdx1 (Wang et al., 2001), we performed electromobility shift assays (EMSA). Nuclear extracts from cells induced with DOX revealed a retarded complex with the known InsFAR target sequence of the insulin gene promoter (Figure 2B, lane 2). Specificity of the complex was demonstrated using a Pdx1 antibody, which inhibited the protein-DNA interaction (Figure 2B, lane 3). Under non-induced conditions a band was visible using the putative Pdx1 binding domain of the TFAM promoter (Figure 2B, lane 4). This complex was more abundant when Pdx1 was over-expressed (Figure 2B, lane 5). This band disappeared in the presence of anti-Pdx1 serum (Figure 2B, lane 6). To substantiate the binding of Pdx1 to the tfam gene promoter in intact cells, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments were performed in the Pdx1-over expressing INS-1 cells. As Pdx1 binds to the gene promoters of insulin and iapp, a 5-fold enrichment was observed when the promoters were amplified from the immuno precipitates. Enrichment was also observed for the tfam gene promoter while MyoD remained unaltered (Figure 2C). The impact of Pdx1 on tfam transcription was assessed in heterologous BHK-21 cells. Transient co-transfections with increasing amounts of a Pdx1 expression plasmid evoked a dose-dependent enhancement of a TFAM promoter/luciferase construct (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Pdx1 interacts and transactivates the rat tfam gene promoter.

A: Schematic representation of the proximal rat tfam gene promoter (-462 to +1) and three of its interacting regulators (Sp1, NRF1 and NRF2) that are essential for transcription of the gene. The putative Pdx1 binding site is shown in the box below. Bold nucleotides represent the core recognition sequence of Pdx1. B: Non-radioactive EMSA using either a biotin-labelled INSFLAT element or the putative Pdx1 binding site of the TFAM promoter. Six ug of nuclear extracts isolated from a clonal INS-1 cell line that conditionally expresses Pdx1 in the presence of doxycycline (rαβ-Pdx1-21) (Wang et al., 2001) were incubated with labelled oligonucleotides. Specificity of the Pdx1 complexes was confirmed by the addition of anti-Pdx1 serum in lanes 3 and 6. C: ChIP assay shown as histograms representing the relative binding of the Pdx1 protein to the TFAM promoter in rαβ-Pdx1-21 treated with doxycycline. After cross-linking, immunoprecipitations were performed with anti-Pdx1 as indicated in the experimental procedures. A non-specific IgG immunoprecipitation was also performed as negative control. Binding capacity to the MyoD (negative control), Ins2 and IAPP (positive controls) as well as to the TFAM promoter was analysed by real-time RT-PCR. Binding intensity data were normalized to MyoD (non-specific binding) and are presented as the mean±S.E.M. for at least three independent experiments. D: Effect of Pdx1 on the transcriptional activation of the tfam gene promoter. Co-transfection studies using BHK-21 cells were performed with a TFAM promoter/luciferase reporter construct and increasing amounts of a Pdx1 expression vector (0.125, 0.25, 0.5 and 1 ug). The pSV-β-galactosidase control vector was used as internal control to normalize for transfection efficiency (approximately 15%). Data are presented as fold induction of basal luciferase activity and expressed as the mean ± SEM of 4-5 independent experiments. ** denotes P<0.01.

Next, we verified Pdx1 binding to the tfam gene promoter in human islets. In silico, nine putative binding sites were identified in the human TFAM promoter (Figure 3A). Of these, TFAM2, 4, 6 and 8 exhibited bona fide interactions with Pdx1 as demonstrated by ChIP experiments (Figure 3B). Taken together, these results clearly show that Pdx1 binds to the TFAM promoter and activates its transcription.

Figure 3. Pdx1 binds to the human tfam gene promoter.

A: Putative Pdx1 binding sites identified in the 5’flanking region of the human tfam gene. Bold nucleotides correspond to the core recognition sequence of Pdx1. Location of each sequence relative to the transcriptional initiation site is provided in brackets. B: Histograms representing the relative binding of the Pdx1 protein to the TFAM promoter in human islets. After cross-linking, immunoprecipitations were performed with anti-Pdx1 as indicated in the experimental procedures. Binding capacity to the Actin B (ActB, negative control), insulin (Ins, positive control) and the TFAM (TFAM1 to 9) promoter was analysed by real-time RT-PCR. Binding intensity data were normalized to ActB (non-specific binding) and are presented as the mean±S.E.M. for at least three independent experiments. * denotes P < 0.05.

TFAM rescues mitochondrial gene expression and copy number

To evaluate whether TFAM is a key factor linking Pdx1 to mitochondrial function as suggested previously (Gauthier et al., 2004), rat islets were infected with a TFAM encoding adenovirus (AdrTFAM). Increasing concentrations of the virus resulted in graded overexpression of TFAM mRNA (Figure 4A). The overexpressed TFAM protein was correctly targeted to the mitochondria, and was absent from the cytosolic fraction (Figure 4B). Further experiments were conducted with the lower viral concentration. Such transduced islets were used to monitor the expression of the mtDNA encoded respiratory chain complex 1 subunit ND1. In islets infected with AdRIPDN79PDX1, the ND1 transcript was decreased by 60% (Figure 4C; (Gauthier et al., 2004)). Under these experimental conditions, we have shown that DN79PDX1 protein levels are 10-fold higher than those of endogenous Pdx1 (Gauthier et al., 2004). TFAM increased ND1 mRNA partially correcting the defect of islets expressing DN79PDX1 but failed to augment ND1 expression in control islets (Figure 4C). In contrast, TFAM overexpression did not attenuate the increase of the nuclear encoded succinate dehydrogenase transcript, which is upregulated by DN79PDX1 (Gauthier et al., 2004). Apart from regulating mtDNA transcription, TFAM is known to control copy number of the mitochondrial genome (Ekstrand et al., 2004; Scarpulla, 2008). Consistent with these findings, islets expressing DN79PDX1 exhibited a 35% decrease in ND1 mtDNA while the nuclear gene succinate dehydrogenase remained constant. TFAM expression protected against DN79PDX1-mediated lowering of ND1 DNA confirming the role of TFAM in stabilising mtDNA (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Adenoviral-mediated overexpression of TFAM in DN79PDX1 expressing rat islets partially restores NADH DH ND1 transcript levels.

Rat islets were transduced with either 4 or 17 X 105 viral particles/islet of AdrTFAM and cultured for 48 hours. RNA as well as cytosolic and mitochondrial protein fractions were subsequently isolated and levels of TFAM transcript (A) and protein (B) were estimated by real time RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. C: Expression levels of NADH DH ND1 and succinate dehydrogenase (SUC DH) were evaluated by real time RT-PCR in islets infected with the indicated adenoviral constructs. Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene cyclophilin and compared to islets infected with AdCaLacZ. Data are the means ± SE of 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate. * denotes P < 0.05.

Figure 5. Mitochondrial DNA copy number is decreased in islets expressing DN79PDX1 and is restored by TFAM.

Rat islets were transduced with the indicated adenoviruses (4 X 105 viral particles/islet) and genomic DNA (nuclear and mitochondrial) was isolated 48 hours post infection. Real time PCR was then performed in order to evaluate gene copy number of NADH DH ND1 (mitochondrial) and SUC DH (nuclear). Values were normalized to the housekeeping gene cyclophilin and compared to islets infected with AdCaLacZ. Data are the means ± SE of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. * denotes P < 0.01.

TFAM restores metabolism-secretion coupling

Glucose-induced ATP generation in the β-cell is a measure of respiratory chain activity (Wiederkehr and Wollheim, 2008). ATP was monitored in living cells using cytosolic luciferase as previously described (Gauthier et al., 2004). Islets expressing DN79PDX1 displayed a markedly reduced ATP response to 16.5 mM glucose relative to control islets (75% reduction; Figure 6A). Overexpression of TFAM did not change glucose-evoked ATP generation under control conditions but restored ATP responses in islets transduced with AdRIPDN79PDX1 (Figure 6A). TFAM was able to completely normalise defective GSIS of the DN79PDX1 expressing islets (Figure 6B). Of note, viral infection over 48 hours did not alter islet insulin content (data not shown). These results suggest a link between mitochondrial metabolism and Pdx1 action, most probably mediated through TFAM expression.

Figure 6. Overexpression of TFAM in DN79Pdx1-infected islets restores both glucose-induced ATP production and insulin secretion.

Rat islets were infected with the indicated adenoviruses (4 X 105 viral particles/islet) along with the adenoviral construct encoding the ATP-sensitive bioluminescence probe luciferase and cultured for 48 hours. A: Cytosolic ATP production in response to 16.5 mM glucose was then determined over a period of 25 min. Luminescence was recorded in a FLUOstar Optima apparatus. Islets were equilibrated in KRBH buffer for 30 min prior to initiation of recording. Glucose (stripped bar) and azide (grey bar) were added at indicated times. Results are the mean ± SE of at least 4 experiments performed in duplicates. B: Insulin secretion was assessed in 30 min static incubations in response to 2.5 mM (white bars) or 16.5 mM glucose (black bars). Insulin released in KRBH was quantified by EIA and expressed as a percentage of total cellular insulin content. Results are the mean ± SE from 4 independent experiments performed in duplicates. **, P < 0.01.

CGP37157 rescues signalling and insulin secretion

Impaired ATP synthesis and GSIS are associated with lowered cytosolic and mitochondrial calcium responses. Mitochondrial calcium serves as a potentiating signal in mitochondrial energy metabolism (Wiederkehr and Wollheim, 2008). Lowered mitochondrial calcium could therefore contribute to the observed defect in metabolism secretion coupling of islets with impaired Pdx1 function. Indeed, expression of DN79PDX1 in islets lowered the mitochondrial calcium response to glucose (Figure 7A, B). During glucose stimulation mitochondrial calcium enters through the calcium uniporter, while extrusion of the ion occurs mainly via the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (mNCE). The benzothiazepine CGP37157 blocks mNCE and amplifies the action of glucose on mitochondrial Ca2+ and increases GSIS (Lee et al., 2003). Acute addition of CGP37157 to Pdx1-deficient islets restored the effect of glucose on mitochondrial Ca2+ (Figure 7A right panel and B). This rise in calcium should accelerate oxidative metabolism and promote ATP synthesis. Consistent with this premise, addition of CGP37157 to DN79PDX1 expressing islets resulted in complete normalization of glucose-induced ATP generation (Figure 7C). In parallel, the attenuated GSIS observed in islets transduced with RIPDN79PDX1 was restored (Figure 7D). At the low CGP37157 concentration (0.1 μM) applied, the compound did not affect mitochondrial calcium, cytosolic ATP responses nor enhance insulin secretion from control islets.

Figure 7. CGP37157 restores the defective mitochondrial calcium response, ATP production and insulin secretion of rat islets expressing DN79PDX1.

Rat islets were co-infected with the adenovirus rAd-CAG-mitoAequorin for the measurement of mitochondrial calcium and either LacZ AdlacZ (control) or AdRIPDN79PDX1 adenovirus. A, left panel: Expression of DN79PDX1 (grey trace) reduces the mitochondrial calcium response to glucose when compared to control islets infected with AdlacZ virus (black trace). A, right panel: Comparison of the mitochondrial calcium response to glucose of islets expressing DN79PDX1 in the presence (black trace) and absence (grey trace) of 0.1 uM CGP37157. CGP37157 was added 2 minutes prior to glucose as indicated. B: During the 5 minutes following initiation of the glucose response the mitochondrial calcium concentration above basal was integrated and expressed as the % of the AdLacZ infected control islets. C: Isolated rat islets were infected with the indicated adenoviruses (4 X 105 viral particles/islet) along with the adenoviral construct encoding the ATP-sensitive bioluminescence probe luciferase and cultured for 48 hours. 0.1 uM CGP37157 was added just prior to ATP measurement. Cytosolic ATP production in response to 16.5 mM glucose was evaluated over a period of 25 min. Islets were equilibrated in KRBH buffer for 30 min and luminescence was subsequently recorded in a FLUOstar Optima apparatus. Glucose (stripped bar) and azide (grey bar) were added at indicated times. Results are the mean ± SE of at least 4 experiments performed in duplicates. D: Insulin secretion was assessed in 30 min static incubations in response to 2.5 mM or 16.5 mM glucose in the presence or absence of 0.1 uM CGP37157. Insulin released in KRBH was quantified by EIA and expressed as a percentage of total cellular insulin content. Results are the mean ± SE from 4 independent experiments performed in duplicates. **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is the unexpected transcriptional control of the ubiquitously expressed nuclear encoded mitochondrial transcription factor TFAM by Pdx1 in the β-cell. Pax4, another β-cell-enriched transcription factor controls the widely expressed genes c-myc and bcl-xl (Brun et al., 2004). In this manner, β-cell function and survival is ensured through the appropriation of non-selective cellular regulators. We demonstrate that acute suppression of Pdx1 in adult mice down regulates TFAM, which based on our results, should contribute to impaired insulin secretion and hyperglycemia in these animals (Holland et al., 2005; Holland et al., 2002). In contrast, TFAM mRNA was not significantly reduced when Pdx1 transcript levels were only modestly decreased by 23% in Pdx1+/− mouse islets (Brissova et al., 2002). This discrepancy may be related to a gene dosage effect of Pdx1 depletion. In good agreement with the results obtained in acutely Pdx1 depleted mice, rat islets transduced with a dominant negative variant of Pdx1 (DN79PDX1) displayed a 50 to 60% reduction in TFAM mRNA levels (Gauthier et al., 2004).

We have demonstrated direct binding of Pdx1 to the human and the rat tfam gene promoter. Moreover, Pdx1 induced transcriptional activation of the rat promoter. These results make it unlikely that DN79PDX1 effects TFAM expression in a non-specific manner. The latter is substantiated by the maintained expression of other homeodomain transcription factor targets such as the Pax4 regulated bcl-xl gene (Brun et al., 2004; Gauthier et al., 2004). Expression of this gene is also normal in another Pdx1 heterozygous mouse model (Johnson et al., 2003). Interestingly, several Pdx1 binding sites were revealed up to 3 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site in the human promoter, whereas only a single site was found in the rat gene. It appears that the basal transcriptional control of TFAM is exerted through the binding of NRF1, NRF2 and SP1 as well as hStaf/ZNF143 to the proximal promoter region (Gerard et al., 2007; Scarpulla, 2008), while Pdx1 binding further upstream may confer β-cell autonomous regulation.

Our earlier work suggested that 56 transcripts were downregulated in Pdx1-deficient rat islets, including the mtDNA-encoded polypeptides of the respiratory chain such as the Nd1 subunit of complex I (Gauthier et al., 2004). TFAM overexpression practically normalized Nd1 mRNA levels. In contrast, the adaptive elevated transcript of the nuclear encoded succinate dehydrogenase remained high, perhaps explained by the relatively short islet culture period (48 hrs). TFAM is known not only to control mtDNA transcription but also to stabilize the mitochondrial genome by substituting histone function (Ekstrand et al., 2004; Scarpulla, 2008). Indeed, we found that the decreased nd1 gene copy number in DN79PDX1 islets was restored after TFAM overexpression. Remarkably, the sole overexpression of TFAM in islets with deficient Pdx1 function completely restored glucose-induced ATP generation as well as insulin secretion. These results establish TFAM regulation as the causal link between loss of Pdx1 function and defective respiratory chain activity.

β-cell specific ablation of TFAM results in defective insulin secretion and time dependent loss of β-cell mass (Silva et al., 2000). Similarly, pdx1+/− mice develop hyperglycaemia and age dependent β-cell apoptosis in vivo correlating with increased susceptibility to cell death in vitro (Johnson et al., 2003). Such susceptibility was also inferred from the gene profile of DN79PDX1 islets with increased caspase-3 and decreased Bcl-2 mRNA levels (Gauthier et al., 2004). It is of interest in this context, that TFAM transcript levels in rat insulinoma INS-1E cells are 4 times higher than those of rat islets and liver (B.R.G. and C.B.W, unpublished results). This may contribute to the resistance of INS-1E cells to palmitate-induced apoptosis compared to primary β-cells (Lai et al., 2008). Along the same line, TFAM overexpression has been reported to protect cardiomyocytes from glucose-induced oxidative stress by increasing mtDNA copy number and preserving respiratory chain function (Suarez et al., 2008). Similarly, TFAM transgenic mice are protected from age-dependent memory impairment and mitochondrial DNA damage in brain microglia (Hayashi et al., 2008). Of note, a TFAM genetic variant has been associated with Alzheimer’s disease in several populations (Belin et al., 2007; Bertram et al., 2007). The published results together with our findings strongly implicate TFAM in the preservation of mitochondrial function.

This conclusion is substantiated by the acute restoration by CGP37157 of mitochondrial calcium elevation and ATP generation in glucose-stimulated Pdx1 deficient islets. It is of particular interest that glucose-induced insulin secretion was completely normalized by this inhibitor of the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger demonstrating that the rise in mitochondrial calcium can compensate for reduced levels of mtDNA encoded respiratory chain complex subunits. CGP37157 was previously shown to enhance GSIS (Lee et al., 2003) as well as hyperpolarizing the mitochondrial membrane potential and generating NAD(P)H (Luciani et al., 2007). Despite evidence of mitochondrial activation in the latter study, Luciani et al., reported dose-dependent inhibition of voltage-gated Ca2+ influx in mouse islet β-cells. At 0.1 μM CGP37157, GSIS but not calcium signalling was inhibited. This contrasts markedly, with the unaltered GSIS in control islets exposed to CGP37157 observed in the present study. Whatever the reason for this discrepancy on insulin secretion, under conditions of limited mitochondrial function, CGP37157 appears to facilitate glucose action in the β-cell by restoring the mitochondrial calcium signalling and ATP synthesis. A similar beneficial effect of CGP37157 on ATP synthesis and hormone-mediated calcium signalling was reported in skin fibroblasts from patients with isolated mitochondrial complex I mutations (Visch et al., 2004). Likewise, a mutation in the mtDNA encoded tRNALys causes a global impairment of mitochondrial protein synthesis, resulting in deficits in both respiratory chain function and in oxidative phosphorylation manifested as myoclonic epilepsy. In cells expressing this mutation, treatment with CGP37157 dramatically restored not only the calcium signal but also ATP generation (Brini et al., 1999).

Pdx1 is undisputed as the crucial transcription factor required for pancreas development and maintenance of differentiated β-cell function, in particular normal glucose regulation of insulin secretion. The present work establishes a direct link between Pdx1 transcriptional activity and mitochondrial signal generation in the moment-to-moment control of insulin release. The latter is achieved through the product of the nuclear gene TFAM that ensures mitochondrial DNA stability and transcription. TFAM down-regulation as a consequence of Pdx1 deficiency can be overcome either by genetic restoration of TFAM expression or by pharmacological enhancement of mitochondrial calcium signalling. Both of these approaches normalize glucose-stimulated insulin secretion caused by Pdx1 loss of function. In view of our results, screening of TFAM genetic variants might be warranted in Type 2 diabetic patients with impaired insulin secretion.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Rats and transgenic mice

7-week-old male Wistar rats (250 g) were purchased from Elevage Janvier (Le Genest-St-Isle, France). Pdx1tTA/tTA; TgPdx1 transgenic mice bearing a conditionally DOX-repressed pdx1 transgene were obtained from Dr Raymond MacDonald (University of Southwestern Medical Center, TX, USA). A detailed description on the generation of these mice is provided in references (Holland et al., 2005; Holland et al., 2002). Doxycycline was initially administered to 6 month-old males by a single intraperitoneal injection (100 mg/kg in final volume of 250 ul of water) and was subsequently maintained in the drinking water (1g DOX/L) for 14 consecutive days. Glycaemia was monitored daily using a Precision Xceed apparatus (Abbott AG, Baar, CH). Hyperglycaemic animals were sacrificed and pancreas extracted for islet isolation.

Islet isolation and cell culture

Pancreatic islets were isolated by collagenase digestion, handpicked and maintained in 11.1 mM glucose/RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Brunschwig AG, Basel, Switzerland), 100 Units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma Basel, Switzerland) (Ishihara et al., 1999). INS-1 cells conditionally expressing Pdx1 (Wang et al., 2001) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Brunschwig AG, Basel, Switzerland) and other additions as described previously (Asfari et al., 1992). Pdx1 expression was induced by the addition of DOX to the media.

Recombinant adenoviral construction and islet transduction

The rat TFAM (rTFAM) cDNA was amplified from poly(A) RNA isolated from liver. The 730 bp amplicon generated using oligonucleotides spanning the START codon (5’-CGC TAG CAT GGC GCT GTT CCG GGG AAT G-3’; NheI site shown in italic and START codon underlined) and STOP codon (5’-CTC TAG ATT AAT TCT CAG AGA TGT C-3’; XbaI site shown in italic and STOP codon underlined) was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega Corp, Madison, WI, USA). Positive clones were sequenced to confirm integrity of the coding region. The rTFAM cDNA was then excised using the restriction enzymes NheI and XbaI, gel purified and subcloned into the NheI/XbaI sites of the pCMV/DLDU6 vector. The latter vector was derived from pDLDU6 (Brun et al., 2007) by cloning the CMV promoter DNA fragment into the MluI/PmeI sites. The CMV/TFAM cassette was subsequently transferred into the Adeno-X viral DNA and recombinant adenovirus (AdrTFAM) were produced according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.). The recombinant adenovirus AdRIPDN79PDX1 harbouring the rat insulin 1 promoter and coding sequence of DN79PDX1 was previously described (Gauthier et al., 2004). AdCAlacZ, containing the bacterial β-galactosidase cDNA, was used as a control adenovirus (Ishihara et al., 1999). Eighteen hours post-isolation, islets were infected with various amounts of recombinant adenoviruses (AdCaLacZ, 4 X 105 viral particles/islet; AdRIPDN79PDX1, 4 X 105 viral particles/islet and 4 and 17 X 105 viral particles/islet for AdrTFAM) for 90 min, washed and cultured in RPMI medium for an additional 48 hours.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and 1 μg was converted into cDNA as previously described (Gauthier et al., 1999). Genomic DNA was isolated from rat islets using the Qiagen DNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Primers were designed using the Primer Express Software (Applera Europe, Rotkreuz, CH) and sequences can be obtained upon request. The same primers for succinate dehydrogenase, NADH ND1 and cyclophilin were used to amplify genomic DNA and cDNA. Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applera Europe) and PCR products were quantified fluorometrically using the SYBR Green Core Reagent kit. Three distinct amplifications were performed in duplicates for each transcript and mean values were normalized to the mean value of the reference mRNA cyclophilin.

Immunoblot analysis

Mitochondrial and cytosolic protein extract fractions (10 and 20 μg) isolated from either AdLac-Z or AdrTFAM-infected islets were resolved on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred electrophoretically to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 3% Topblock and 0.4% Tween-20 in PBS for 1 h and then left overnight at 4°C in the presence of a rabbit TFAM antibody (kindly provided by Dr. N.G. Larsson, Karolinska Institute, Sweden) at a 1:5000 dilution. A goat anti-rabbit IgG antiserum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:4000) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, CH) was then added for 60 min and immunoreactive products were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico, Pierce, Rockford, IL) following by exposure to X-OMAT Kodak films (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY) for less than 1 min.

Electromobility shift assay (EMSA)

Non-radioactive EMSA was performed using the LightShift chemiluminescent kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL USA). Briefly, 6 ug of nuclear extracts purified from non-induced and doxycycline-induced Pdx1 conditionally expressing INS-1 cells were incubated with either a double stranded biotinylated INSFLAT element of the rat insulin promoter (5’-CCG ATC TTG TTA ATA ATC TAA TTA CC-3’) or with the putative Pdx1 binding site of the rat TFAM promoter (5’-CCA AAG ATT AGA TAA ACA AAG CGA TAC ATT T-3’). Subsequent to electrophoresis, the gel was blotted unto a PVDF membrane and DNA/protein complexes were revealed using a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate as outlined by the manufacturer.

ChIP assay

ChIP assays were performed as described by Parrizas et al. (Parrizas et al., 2003). Briefly, formaldehyde-cross-linked chromatin extracts were prepared from either INS-1 cells conditionally expressing Pdx1 (rαβ-Pdx1-21; 4 X 106 cells/condition) (Wang et al., 2001) or from human islets (1000-2000 islets/condition) and fragmented by sonication. Chromatin extracts (10 ug) were first pre-cleared with Protein G-sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, SE) for 1 hour. After centrifugation (10 g for 2 min at 4 °C) 10% of each supernatant was kept as input while the remaining samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a goat anti-Pdx1 serum (1/500 dilution for human samples and 1:200 for INS-1E samples) kindly provided by Dr Christopher Wright (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA). A rabbit IgG (#sc-2027; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was also used as negative control. DNA/protein/antibody complexes were then incubated for 2 hours with Protein G sepharose beads and subsequently washed sequentially in a low-salt buffer, high-salt buffer, LiCl buffer and finally Tris/EDTA buffer. DNA/protein complexes were then eluted from the beads using a solution containing 1% SDS and 0.1 M NaHCO3. Proteins were eliminated using 400 μg of proteinase K (Qiagen AG, Basel, CH) by incubation at 45 °C for 2 hours. DNA samples were then purified using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen AG). The PCR primers used for analysis of Pdx1 binding to the human and rat tfam gene promoters can be obtained upon request. PCR products were verified on 2% ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels and/or analysed by real-time PCR using an ABI 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applera Europe).

Transient transfection assays

The proximal rat tfam gene promoter was amplified from genomic DNA isolated from pancreatic islets using the following primers: rTFAM-PROM-5’, 5’-AAA GAT TAG ATA AAC AAA GC-3’ and rTFAM-PROM-3’, 5’CAG GGG CTT GTT ATC ATG CC-3’. The amplicon was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega Corp) and sequenced to confirm integrity of the 5’-flanking region. The tfam gene promoter fragment was then excised using the restriction enzyme EcoR1, made blunt ended using the Klenow fragment of the DNA polymerase I, gel purified and subcloned into the SmaI restriction site of the pGL3-Basic luciferase reporter vector (pTFAM/LUC) (Pomega Corp). The BHK-21 cell line was transiently transfected using the calcium phosphate precipitation technique as described previously (Gauthier et al., 2002). Three ug of pTFAM/LUC were co-transfected with increasing amount of a Pdx1 expression vector (0.125, 0.25, 0.5 and 1 ug). The pSV-β-Galactosidase vector (1 ug) (Promega Corp) was used as internal control to normalize for transfection efficiency (approximately 15%) in all experiments. Values correspond to the mean and standard error of at least 4-5 individual transfections performed in duplicates. Results are presented as fold induction of the control sample obtained from cells transfected with empty expression vector.

Insulin secretion assay and ATP measurement

Islets were washed in Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate-HEPES buffer (KRBH; 140 mM NaCl, 3.6 mM KCl, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES, 0.1% BSA) and incubated at 37°C for 60 min in the same buffer supplemented with 2.5 mM glucose. Subsequently, insulin secretion from 15 size-matched islets per condition was measured over a period of 30 min in KRBH containing the indicated stimulators. In some instances 0.1 μM CGP37157 was added to the reaction. Total insulin content was extracted using acid ethanol. Insulin was detected using the rat insulin enzyme immunoassay kit as described by the manufacturer (SPI-BIO/Bertin Pharma Biotech Division; Brunschwig, Basel, CH). Secreted insulin was expressed as percentage of total cellular insulin content.

Alterations in cytosolic ATP levels in response to 16.5 mM glucose, or 0.1 μM CGP37157/16.5 mM glucose were monitored using the adenoviral construct AdCAGLuc encoding the ATP-sensitive bioluminescence probe luciferase (Ishihara et al., 2003). Islets were preincubated at 37°C for 30 min in KRBH before the addition of 2.5 mM glucose and 500 μM beetle luciferin (Promega, Madison, WI). Changes in ATP were then recorded using a FLUOstar Optima apparatus (BMG Labtechnologies) as previously described by Merglen et al. (Merglen et al., 2004).

Mitochondrial calcium measurements

Mitochondrial calcium signals were measured using an adenovirus expressing mitochondrially targeted Aequorin as described previously (Brun et al., 2004). Rat islets were co-infected with Ad-CAG-mitoAequorin (4 × 107 pfu/ml) along with either a control AdLacZ virus or the AdRIPDN79PDX1. After infection islets were washed and seeded onto A431 matrix-coated cover slips. Two days after infection the islets were analysed as previously described (Brun et al., 2004). Where indicated, 0.1 μM CGP37157 was added prior to glucose stimulation.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean+/− SE. Where indicated, the statistical significance of the differences between groups was estimated by Student’s t-test. * and ** indicate statistical significance with p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Dominique Duhamel, Eve Julie Sarret, Dale Brighouse and Nicole Aebischer. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant no. 32-66907.01 (C.B.W. and B.R.G.), 310000-116750/1 (C.B.W., A.W. and B.R.G.) and 310030-119763 (B.R.G.) as well as by a European-Community-funded project under framework program 6 (EuroDia; LSHM-CT-2006-518153).

Abbreviations

- Pdx1

Pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1

- MODY

Maturity onset diabetes of the young

- DOX

Doxycycline

- KRBH

Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate-HEPES buffer

- GSIS

glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- IAPP

islet amyloid polypeptide

- EMSA

electron mobility shift assay

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Asfari M, Janjic D, Meda P, Li G, Halban PA, Wollheim CB. Establishment of 2-mercaptoethanol-dependent differentiated insulin-secreting cell lines. Endocrinology. 1992;130:167–178. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.1.1370150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin AC, Bjork BF, Westerlund M, Galter D, Sydow O, Lind C, Pernold K, Rosvall L, Hakansson A, Winblad B, Nissbrandt H, Graff C, Olson L. Association study of two genetic variants in mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2007;39:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brini M, Pinton P, King MP, Davidson M, Schon EA, Rizzuto R. A calcium signaling defect in the pathogenesis of a mitochondrial DNA inherited oxidative phosphorylation deficiency. Nat Med. 1999;5:951–954. doi: 10.1038/11396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissova M, Shiota M, Nicholson WE, Gannon M, Knobel SM, Piston DW, Wright CV, Powers AC. Reduction in pancreatic transcription factor PDX-1 impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11225–11232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun T, Duhamel DL, Hu He KH, Wollheim CB, Gauthier BR. The transcription factor Pax4 acts as a survival gene in the insulinoma INS1E cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:4261–4271. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun T, Franklin I, St-Onge L, Biason-Lauber A, Schoenle E, Wollheim CB, Gauthier BR. The diabetes-linked transcription factor Pax4 promotes beta-cell proliferation and survival in rat and human islets. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1123–1135. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand MI, Falkenberg M, Rantanen A, Park CB, Gaspari M, Hultenby K, Rustin P, Gustafsson CM, Larsson NG. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mtDNA copy number in mammals. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:935–944. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbein SC, Das SK, Hallman DM, Hanis CL, Hasstedt SJ. Genome-wide linkage and admixture mapping of type 2 diabetes in African American families from the American Diabetes Association GENNID (Genetics of NIDDM) Study Cohort. Diabetes. 2009;58:268–274. doi: 10.2337/db08-0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenberg M, Larsson NG, Gustafsson CM. DNA replication and transcription in mammalian mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:679–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.152028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier B, Robb M, McPherson R. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene expression during differentiation of human preadipocytes to adipocytes in primary culture. Atherosclerosis. 1999;142:301–307. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier BR, Brun T, Sarret EJ, Ishihara H, Schaad O, Descombes P, Wollheim CB. Oligonucleotide microarray analysis reveals PDX1 as an essential regulator of mitochondrial metabolism in rat islets. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31121–31130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier BR, Duhamel DL, Iezzi M, Theander S, Saltel F, Fukuda M, Wehrle-Haller B, Wollheim CB. Synaptotagmin VII splice variants {alpha}, {beta}, and {delta} are expressed in pancreatic {beta}-cells and regulate insulin exocytosis. Faseb J. 2008;22:194–206. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8333com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier BR, Schwitzgebel VM, Zaiko M, Mamin A, Ritz-Laser B, Philippe J. Hepatic Nuclear Factor-3 (HNF-3 or Foxa2) Regulates Glucagon Gene Transcription by Binding to the G1 and G2 Promoter Elements. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:170–183. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard MA, Krol A, Carbon P. Transcription factor hStaf/ZNF143 is required for expression of the human TFAM gene. Gene. 2007;401:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Yoshida M, Yamato M, Ide T, Wu Z, Ochi-Shindou M, Kanki T, Kang D, Sunagawa K, Tsutsui H, Nakanishi H. Reverse of age-dependent memory impairment and mitochondrial DNA damage in microglia by an overexpression of human mitochondrial transcription factor a in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8624–8634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1957-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiriart M, Aguilar-Bryan L. Channel regulation of glucose sensing in the pancreatic {beta}-cell. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1298–E1306. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90493.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AM, Gonez LJ, Naselli G, Macdonald RJ, Harrison LC. Conditional expression demonstrates the role of the homeodomain transcription factor Pdx1 in maintenance and regeneration of beta-cells in the adult pancreas. Diabetes. 2005;54:2586–2595. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AM, Hale MA, Kagami H, Hammer RE, MacDonald RJ. Experimental control of pancreatic development and maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12236–12241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192255099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara H, Maechler P, Gjinovci A, Herrera PL, Wollheim CB. Islet beta-cell secretion determines glucagon release from neighbouring alpha-cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:330–335. doi: 10.1038/ncb951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara H, Wang H, Drewes LR, Wollheim CB. Overexpression of monocarboxylate transporter and lactate dehydrogenase alters insulin secretory responses to pyruvate and lactate in beta cells. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1621–1629. doi: 10.1172/JCI7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MV, Joseph JW, Ronnebaum SM, Burgess SC, Sherry AD, Newgard CB. Metabolic cycling in control of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1287–E1297. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90604.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, Ahmed NT, Luciani DS, Han Z, Tran H, Fujita J, Misler S, Edlund H, Polonsky KS. Increased islet apoptosis in Pdx1+/− mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1147–1160. doi: 10.1172/JCI16537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai E, Bikopoulos G, Wheeler MB, Rozakis-Adcock M, Volchuk A. Differential activation of ER stress and apoptosis in response to chronically elevated free fatty acids in pancreatic beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E540–E550. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00478.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson NG, Rustin P. Animal models for respiratory chain disease. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:578–581. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Miles PD, Vargas L, Luan P, Glasco S, Kushnareva Y, Kornbrust ES, Grako KA, Wollheim CB, Maechler P, Olefsky JM, Anderson CM. Inhibition of mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchanger increases mitochondrial metabolism and potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in rat pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2003;52:965–973. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciani DS, Ao P, Hu X, Warnock GL, Johnson JD. Voltage-gated Ca(2+) influx and insulin secretion in human and mouse beta-cells are impaired by the mitochondrial Na(+)/Ca(2+) exchange inhibitor CGP-37157. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;576:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maassen JA, Janssen GM, t Hart LM. Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial diabetes (MIDD) Ann Med. 2005;37:213–221. doi: 10.1080/07853890510007188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maechler M, CB W. Mitochondrial functioning in normal and diabetic beta cells. Nature. 2001;414:807–812. doi: 10.1038/414807a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merglen A, Theander S, Rubi B, Chaffard G, Wollheim CB, Maechler P. Glucose sensitivity and metabolism-secretion coupling studied during two-year continuous culture in INS-1E insulinoma cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:667–678. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Krasinski JM, Stoffers DA. On the origin of the beta-cell. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1998–2021. doi: 10.1101/gad.1670808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrizas M, Boj SF, Luco RF, Maestro MA, Ferrer J. Chromatin immunoprecipitation using isolated islets of Langerhans. Methods Mol Med. 2003;83:61–71. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-377-1:061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional paradigms in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:611–638. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servitja JM, Ferrer J. Transcriptional networks controlling pancreatic development and beta cell function. Diabetologia. 2004;47:597–613. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JP, Kohler M, Graff C, Oldfors A, Magnuson MA, Berggren PO, Larsson NG. Impaired insulin secretion and beta-cell loss in tissue-specific knockout mice with mitochondrial diabetes. Nat Genet. 2000;26:336–340. doi: 10.1038/81649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez J, Hu Y, Makino A, Fricovsky E, Wang H, Dillmann WH. Alterations in mitochondrial function and cytosolic calcium induced by hyperglycemia are restored by mitochondrial transcription factor A in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1561–C1568. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00076.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visch HJ, Rutter GA, Koopman WJ, Koenderink JB, Verkaart S, de Groot T, Varadi A, Mitchell KJ, van den Heuvel LP, Smeitink JA, Willems PH. Inhibition of mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchange restores agonist-induced ATP production and Ca2+ handling in human complex I deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40328–40336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Maechler P, Ritz-Laser B, Hagenfeldt KA, Ishihara H, Philippe J, Wollheim CB. Pdx1 level defines pancreatic gene expression pattern and cell lineage differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25279–25286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederkehr A, Park KS, Dupont O, Demaurex N, Pozzan T, Cline GW, Wollheim CB. Matrix alkalinization: a novel mitochondrial signal for sustained pancreatic beta-cell activation. EMBO J. 2009;28:417–428. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederkehr A, Wollheim CB. Minireview: implication of mitochondria in insulin secretion and action. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2643–2649. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederkehr A, Wollheim CB. Impact of mitochondrial calcium on the coupling of metabolism to insulin secretion in the pancreatic beta-cell. Cell Calcium. 2008;44:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]