Abstract

Perpetrator and incident characteristics were studied in regard to incidents of emotional, physical, and sexual mistreatment of older adults (age 60 +) in national sample of older men and women. Random Digit Dialing (RDD) across geographic strata was used to compile a nationally representative sample; Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) was used to standardize collection of demographic, mistreatment, and perpetrator and incident characteristics data. The final sample size consisted of 5,777 older adults. Approximately one in ten adults reported at least one form of mistreatment, and the majority of incidents were not reported to authorities. Perpetrators of physical mistreatment against men had more “pathological” characteristics compared to perpetrators of physical mistreatment against women. Perpetrators of physical mistreatment (compared to emotional and sexual mistreatment) also evidenced increased likelihood of legal problems, psychological treatment, substance use during incident, living with victim, and being related to the victim. Implications for future research and social policy are discussed.

Elder mistreatment refers to intentional actions that result in harm or serious risk of harm to an elder by a caregiver, or failure by a caregiver to protect the elder from harm or meet the elder’s basic needs (National Research Council, 2003). The primary types of elder mistreatment include physical, emotional, and sexual mistreatment (e.g., Acierno et al., in press; Biggs, Manthorpe, Tinker, Doyle, & Erens, 2009; McCreadie et al., 2006). Nationally representative studies in the United States have begun to document the prevalence of elder mistreatment. The National Elder Mistreatment Incidence Study (Tatara, 1997) found that 449,924 persons aged 60 or older had been mistreated some way in 1996. Laumann, Leitsch, and Waite (2008) found among a sample of 3,005 individuals aged 57 to 85 that 9.0% reported verbal mistreatment; 0.2% reported physical mistreatment, and 3.5% reported financial mistreatment. Acierno and colleagues (in press) recently found among a sample of 5,777 older adults aged 60 and above that 5.1% report emotional mistreatment, 1.6% report physical mistreatment, and .6% report sexual mistreatment in the past year. These studies demonstrate that elder mistreatment is a relatively prevalent problem for older adults.

Elder mistreatment has been associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes. Amstadter and colleagues (in press) found that a recent history of physical mistreatment and emotional mistreatment were significantly related to poorer self-reported physical health among a large national sample of older adults. Stein and Barret-Connor (2000) similarly found in a large sample of older adults residing in southern California that a lifetime history of sexual mistreatment was associated with increased risk of arthritis, breast cancer, and thyroid disease. These findings echo a larger literature demonstrating an inverse relation between potentially traumatic event (PTE) exposure and physical health (Kendall-Tackett, 2009; Sledjski, Speisman, & Dierker, 2008). Research also suggests a relation between elder mistreatment and depression. Large surveys in Europe (Cooper et al., 2006; Garre-Olmo et al., 2009) and India (Chokkanathan & Lee, 2005) suggest that depression is greater among older adults who report elder mistreatment. One study in the United States conducted in the state of Iowa (Buri, Daly, Hartz, & Jogerst, 2006) also found a positive relation between elder mistreatment and depression, but in this study the relationship between mistreatment and depression was only found among older adults who did not receive help from a caregiver in completing the survey.

Given evidence of the negative outcomes associated with elder mistreatment, it is important to identify factors that may increase or decrease risk associated with victimization. There are some characteristics of the older adult that may increase risk for elder mistreatment. Marital status (being divorced or separated relative to widowed), health status (poorer health relative to fair or good health), and less participation in social activities have been shown to be associated with an increased likelihood of being mistreated (Biggs et al., 2009; Racic, Kusmuk, Kozomara, Debelnogic, & Tepic, 2006). Younger age may be a risk factor for verbal mistreatment and financial mistreatment (Laumann et al., 2008). Age also appears to interact with health status to predict mistreatment likelihood, such that younger aged elderly who are in poor health are more likely to be mistreated, particularly neglected (Biggs et al., 2009). Biological sex correlates with mistreatment, with elderly women more likely to be mistreated compared to elderly men (Biggs et al., 2009; Pillemer & Finkelhor, 1988; Yaffe, Weiss, Wolfson, & Lithwick, 2007). Among women, younger age (ages 50–59) is associated with increased rates of mistreatment relative to older ages (Klein, Tobin, Salomon, & Dubois, 2008). The type of mistreatment received also differs by age among women, with intimate mistreatment becoming less likely as women get older while risk for mistreatment from other family members increases (Klein et al., 2008).

While research is illuminating characteristics of the older adult that are associated with mistreatment, far less research has investigated incident characteristics and characteristics of the perpetrator that are involved in elder mistreatment cases. The perpetrator is frequently a spouse or other family member, whereas mistreatment by a care worker or a close friend happens comparatively less frequently (Biggs et al., 2009; Moon, Lawson, Carpiac, & Spaziano, 2006; Tatara, 1997; Zink & Fisher, 2007). For example, Biggs et al. (2009) found among a UK sample that 51% of elderly mistreatment was perpetrated by a spouse, 49% by another family member, compared to 18% by a care worker or close friend. Some data from a small sample of criminal cases suggest that sexual assault is most frequently perpetrated by younger males (aged 16–31), and that perpetrators of sexual mistreatment of the elderly generally have histories of prior criminal behavior (Jeary, 2005). Perpetrators of interpersonal mistreatment are more likely to be men, older, and living with the victim (Biggs et al., 2009). There is some evidence from a small sample of perpetrators who have admitted to elder mistreatment indicating that perpetrators of physical mistreatment are more likely to have a history of alcohol abuse and to have been the victim of physical mistreatment during childhood (Reay & Brown, 2001).

These data are beginning to elucidate characteristics of the perpetrator that are associated with elder mistreatment, but most of the samples from which the data are drawn are either limited in size or restricted to specific geographic locations (e.g., Campbell-Reay & Browne, 2001; Jeary, 2005; Racic et al., 2006; Yaffe et al., 2007). These limitations necessitate the investigation of characteristics of the perpetrator, and incident characteristics, in a large nationally representative sample. Further, there is little research investigating whether perpetrator characteristics interact with characteristics of the victim to increase the likelihood of certain types of mistreatment. For example, do perpetrator and incident characteristics (e.g., the incident being reported to the police, the perpetrator being a family member) differ between male and female victims of various forms of elder mistreatment? The present study sought to examine incident and perpetrator characteristics of the three main forms of elder maltreatment (i.e., physical, emotional, and sexual mistreatment) and to examine if these characteristics differ by sex of the victim in a large, nationally representative sample of US elderly adults.

Method

Sampling

The survey sample was derived using stratified random digit dialing (RDD) with an area probability sample based on Census-defined ‘size of place’ parameters (e.g., rural, urban). The continental US served as the sampling location. A systematic selection procedure (i.e., the ‘most recent birthday method’) was used to designate one respondent for each household sampled. Interviews were conducted in either English or Spanish, depending on participant preference. To increase participant privacy and protection, respondents were asked if they were in a place where they could talk privately, and sensitive questions were worded to elicit a “yes/no” response, rather than a description of the mistreatment event. This method yielded a representative sample (weighted based on age and sex to match 2005 Census estimates) of 5,777 older adults age 60 or above. Interviewers determined if the designated participant clearly possessed the cognitive capacity to consent to participation, and only these individuals were surveyed. This resulted in 105 cases deemed questionable in terms of ability to consent who were not interviewed. Interviewers used standardized computer assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) procedures to ask participants about a variety of mistreatment experiences, perpetrator and incident characteristics, and demographics. CATI incorporates complex ‘skip-out’ patterns which assures only relevant questions are asked of participants, greatly enhancing interview efficiency. Supervisors listening to real-time telephone interviews while monitoring the CATI interview on their own computer performed random checks of each interviewer’s assessment behavior and data-entry accuracy at least twice during each shift. If an error were detected, supervisors required its correction and discussed the error with the interviewer following the interview. If errors were detected again in following interviews, the interviewer was removed from the study. The field interviewing commenced on February 6, 2008. The cooperation rate was 69%, and was calculated according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research (2004) as the number of completed interviews, including those that screen out as ineligible, divided by the total number of completed interviews, including those that screen out as ineligible, terminated interviews, and refusals to interview. The final average interview length was approximately 16 minutes. For full methodological details see (Acierno et al., in press).

Variable Definitions

Demographic Variables of Participants

Standard demographic variables were assessed, including age (dichotomized into 60–70 and 71+), race/ethnicity, employment status (dichotomized into employed and unemployed), marital status (in three categories: married/cohabitating, single/divorced/separated, and widowed), income (categorized as an annual household income of $35,000 and below, and $35,001 and above), and sex (as male and female).

Mistreatment Variables

Emotional, physical, and sexual mistreatment were assessed. Descriptive parameters of the event were collected after respondents indicated that such an event had occurred.

Emotional mistreatment was defined as an affirmative answer to any one of the following: 1. “Has anyone ever verbally attacked, scolded, or yelled at you so that you felt afraid for your safety, threatened or intimidated?” 2. “Has anyone ever made you feel humiliated or embarrassed by calling you names such as stupid, or telling you that you or your opinion was worthless?” 3. “Has anyone ever forcefully or repeatedly asked you to do something so much that you felt harassed or coerced into doing something against your will?” 4. “Has anyone close to you ever completely refused to talk to you or ignored you for days at a time, even when you wanted to talk to them?”

Physical mistreatment was defined as an affirmative answer to any one of the following: 1. “Has anyone ever hit you with their hand or object, slapped you, or threatened you with a weapon?” 2. “Has anyone ever tried to restrain you by holding you down, tying you up, or locking you in your room or house?” 3. “Has anyone ever physically hurt you so that you suffered some degree of injury, including cuts, bruises, or other marks?”

Sexual mistreatment was defined as an affirmative answer to any one of the following three questions: 1. “Regardless of how long ago it happened or who made the advances, has anyone ever made you have sex or oral sex by using force or threatening to harm you or someone close to you?” 2a. (for females) “Has anyone ever touched your breasts or pubic area or made you touch his penis by using force or threat of force?” 2b. (for males) “Has anyone ever touched your pubic area or made you touch their pubic area by using force or threat of force?” 3a. (for females) “Has anyone ever forced you to undress or expose your breasts or pubic area when you didn’t want to?” 3b. (for males) “Has anyone ever forced you to undress or expose your pubic area when you didn’t want to?”

Perpetrator Characteristics

For each type of mistreatment, characteristics of the perpetrator and incident were assessed. Perpetrator and incident characteristics were chosen on the basis of previous research (Acierno, 2003).

Victim Dependent

To determine if the victim needed the perpetrator, they were asked, “Would you be able to live on your own if that person no longer lived with you?”

Daily Help

Participants were asked, “Did that person ever help you out with any day to day things, like shopping, taking medicines, driving you places, getting dressed, and that type of thing?”

Few Friends

Participants were asked about the social network of the perpetrator, “How many friends did that person have at the time of the incident, would you say: none, very few [1–3], some [4–6], or a lot [7+]?” Responses were categorized into less than three vs. four or more).

Unemployed

To determine if the perpetrator was unemployed, participants were asked, “Did that person have a job at the time of the incident?”

Legal Problems

The participant was asked, “Has that person ever been in trouble with the police?”

Counseling

The participant was also asked, “Has that person ever received inpatient or outpatient counseling for emotional problems?”

Substance Use

To determine if the perpetrator had problems with drugs or alcohol, participants were asked, “Did that person have a problem with alcohol or drugs at the time of the incident?”

Lived With

To determine if the victim lived with the perpetrator, they were asked, “Did that person live with you at the time of the incident, or does he/she live with you now?”

Relative

The victim’s relationship to the perpetrator was assessed by asking, “What was the person’s relationship to you?” Responses were categorized as being a relative or a non-relative.

Reported

The victim reporting mistreatment to police/authorities was assessed by asking, “Thinking about the most recent incident where someone [type of mistreatment], was this incident reported to the police or other authorities?”

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics were utilized to examine perpetrator characteristics for each type of mistreatment. To determine if men vs. women were more likely to experience each type of mistreatment a chi-square analysis was conducted. Next, to examine if perpetrator and incident characteristics differ by sex of the victim, chi-squares analyses were conducted. Given the low number of men who were sexually mistreated in the past year, chi-square analyses were not conducted for that type of mistreatment.

Results

Demographics of the Full Sample

Of the 5,777 older adults, the average age was 71.5 years (SD = 8.1), range of 60 to 97 years; 60.2% (3,477) of the older adults were women and 39.8% (2,300) were men. Of the total, about 56.8% (3,281) were married or cohabitating, 11.8% (677) were separated or divorced, 25.1% (1,450) were widowed, and 5.2% (303) were never married. Considering race in order of magnitude, 87.5% (4,876) indicated that they were White, 6.7% (386) Black, 2.3% (132) American Indian or Alaskan Native, 0.8% (49) Asian, 0.2% (13) Pacific Islander, and the remainder chose not to identify. Considering Ethnicity, 4.3% (245) indicated that they were of Hispanic or Latino origin.

Emotional Mistreatment

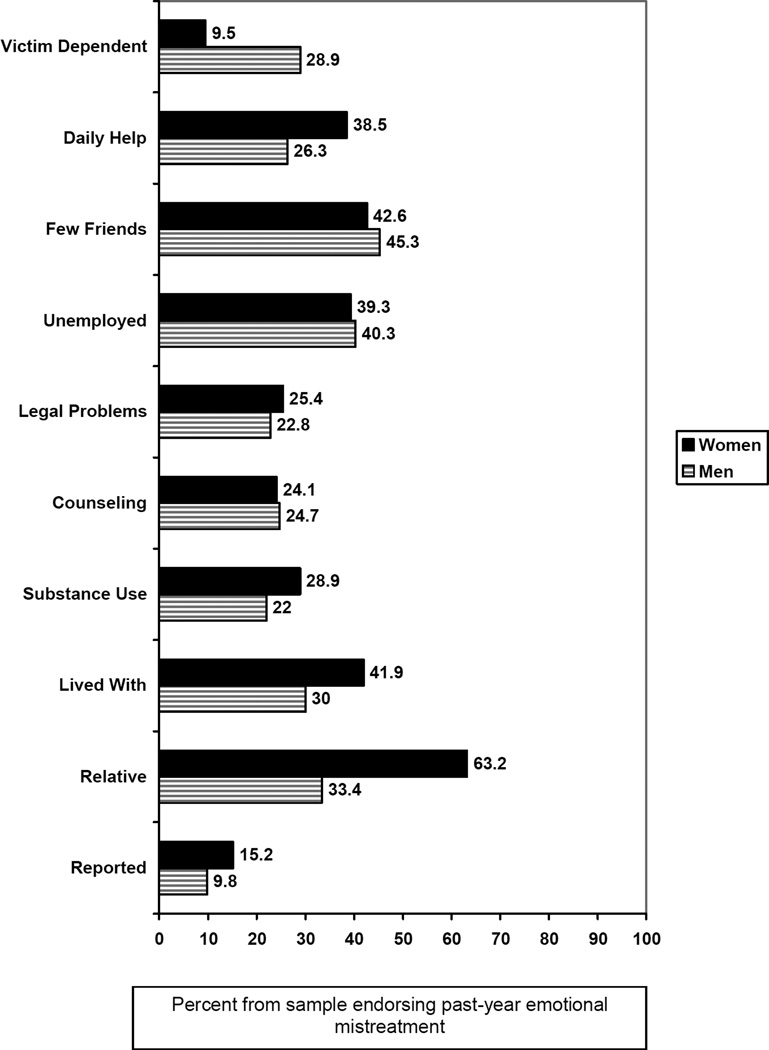

Overall prevalence of past-year emotional mistreatment in our sample of elder individuals was 4.6% (N=254). The prevalence of emotional mistreatment by sex was not significantly different (χ2 =1.98, p=.16). Descriptive statistics may be found in Figure 1, broken down by sex of the victim. Approximately one out of eight victims reported their emotional mistreatment to the police. With regard to perpetrator characteristics, approximately half of all victims said that the perpetrator was a family member or spouse and over one-third of perpetrators were residing with the victim (37.7%) and providing daily assistance at the time of mistreatment (34.2%). Around one-quarter of emotional mistreatment perpetrators had a prior history of legal problems (24.6%), received counseling for emotional problems (24.3%), and had reported problems with substance mistreatment (26.6%). A relatively large proportion, one out of seven victims, reported that they would be unable to live on their own without the assistance provided by the perpetrator.

Figure 1. Perpetrator and Incident Characteristics of Emotional Mistreatment by Victim Gender.

Perpetrator characteristics as reported by victims of past-year elder emotional mistreatment by gender. Characteristics include: victim being dependent on perpetrator for daily care, perpetrator providing daily instrumental help, perpetrator having fewer than 3 friends, perpetrator being unemployed, perpetrator having previous problems with the police, perpetrator having sought counseling, perpetrator having substance use problems, perpetrator living with the victim at the time of mistreatment, perpetrator being a spouse or family member of the victim, and victim reporting mistreatment to police/authorities. Note: Valid percentages are reported.

In regard to differences in perpetrator and incident characteristics by sex of the victim, men who were emotionally mistreated were more likely to be dependent on the perpetrator compared to women who were emotionally mistreated (χ2 =4.53, p=.03). However, women victims were more likely to need help with daily activities (χ2 =9.42, p=.02) than were men victims, and to be perpetrated against from a family member (χ2 =20.63, p<.001). No other sex differences were found for the remaining perpetrator characteristics.

Physical Mistreatment

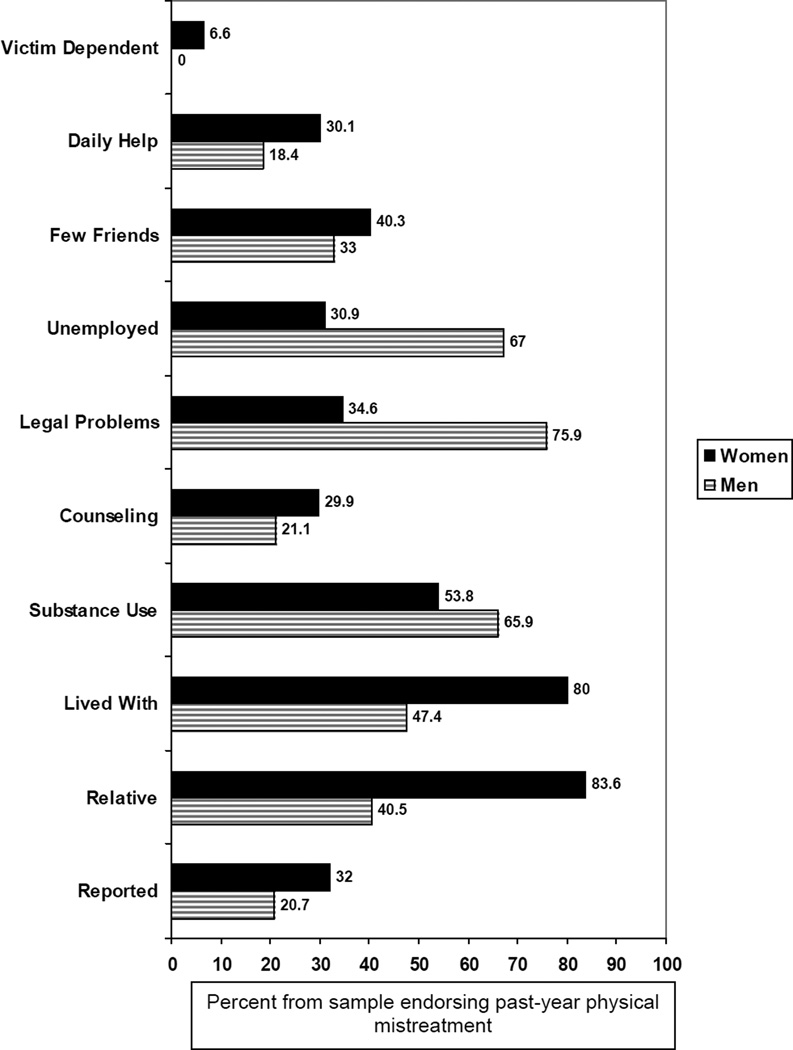

Overall prevalence of past-year physical mistreatment was substantially lower than that of emotional mistreatment, with 1.6% (N=86) reporting such experiences. Prevalence of emotional mistreatment did not differ by sex (χ2 =1.10, p=.29). Over one-quarter of victims reported their physical mistreatment to police. An overwhelming majority of perpetrators (74.9%) were related to the victim and lived with the victim (73.6%) at the time of assault. However, more than twice as many female victims (83%) than male victims (40.5%) reported that their perpetrator lived with them at the time of mistreatment. Interestingly, male victims of physical mistreatment were specifically likely to report that their perpetrator had substance use problems (65.9%), legal problems (75.9%), or were unemployed (67%) at the time of mistreatment. Refer to Figure 2 for additional descriptive statistics.

Figure 2. Perpetrator and Incident Characteristics of Physical Mistreatment by Victim Gender.

Perpetrator characteristics as reported by victims of past-year elder physical mistreatment by gender. Characteristics include: victim being dependent on perpetrator for daily care, perpetrator providing daily instrumental help, perpetrator having fewer than 3 friends, perpetrator being unemployed, perpetrator having previous problems with the police, perpetrator having sought counseling, perpetrator having substance use problems, perpetrator living with the victim at the time of mistreatment, perpetrator being a spouse or family member of the victim, and victim reporting mistreatment to police/authorities. Note: Valid percentages are reported.

Chi-square analyses revealed that compared to women victims, male victims were more likely to be perpetrated against by an unemployed individual (χ2 =3.79, p=.052), and by a perpetrator with a history of legal problems (χ2 =5.36, p=.02). Compared to male victims, female victims of physical mistreatment were more likely to be perpetrated against by a relative (χ2=7.80, p=.005), and a trend was found indicating that women were more likely to be perpetrated against by someone they lived with (χ2 =3.60, p=.06).

Sexual Mistreatment

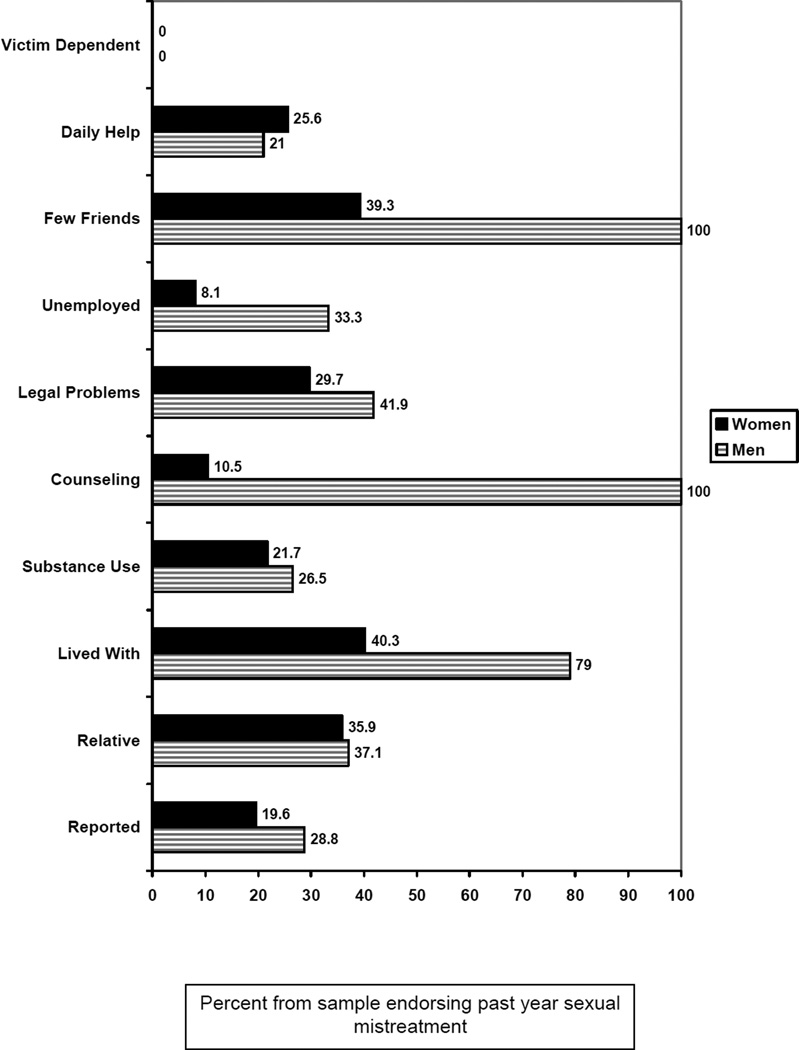

Prevalence of past-year sexual mistreatment in our elder sample was 0.6% (N=34). This form of mistreatment did differ by sex, with more women being victims compared to men (χ2 =5.40, p=.02). Of the participants with a recent history of sexual mistreatment, 21.4% reported the incident to police, with a higher proportion of men (28.8%) than women (19.6%) reporting. Just over one-third of perpetrators were related to the victim (36.1%) and approximately one-half (48%) were residing with the victim at the time of mistreatment. Approximately one-third of perpetrators had prior legal problems, whereas one in five (22.8%) had purported substance use problems. Fewer than ten percent of the perpetrators of sexual mistreatment incidents had ever received counseling for emotional problems. Additional descriptive information on perpetrator characteristics may be found in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Perpetrator and Incident Characteristics of Sexual Mistreatment by Victim Gender.

Perpetrator characteristics as reported by victims of past-year elder sexual mistreatment by gender. Characteristics include: victim being dependent on perpetrator for daily care, perpetrator providing daily instrumental help, perpetrator having fewer than 3 friends, perpetrator being unemployed, perpetrator having previous problems with the police, perpetrator having sought counseling, perpetrator having substance use problems, perpetrator living with the victim at the time of mistreatment, perpetrator being a spouse or family member of the victim, and victim reporting mistreatment to police/authorities. Note: Valid percentages are reported.

Discussion

Overall Findings

Given that the majority of research on perpetrator characteristics focuses on reported cases (e.g., Jeary, 2005; Reay & Brown, 2001), the present results extend the literature by presenting characteristics of cases that are often over-looked or unknown. Another methodological strength of this study was that mistreatment events were initially assessed independent of perpetrator status, thereby permitting specification of proportionate rates of stranger vs. family member mistreatment, whereas most prior research has focused on only one or the other form of victimization. Looking across types of mistreatment, most incidents were not reported to police (ranging from 73.0–86.8%). When comparing across types of mistreatment, a higher proportion of perpetrators of physical mistreatment (compared to emotional and sexual mistreatment) had problems with police, received psychological treatment, were using substances at the time of the incident, lived with the victim, and were related to the victim.

Gender Differences

In contrast to prior research (Biggs et al., 2009; Pillemer & Finkelhor, 1988; Yaffe et al., 2007) the present study did not find that elderly women were more likely to be mistreated compared to elderly men. However, key gender differences were found for characteristics of the incidents of mistreatment, and characteristics of the perpetrators of various forms of mistreatment. Three key differences were found by gender of victims of emotional mistreatment. Women were more likely than men to need daily help with activities (39% vs. 26%) and to be perpetrated against by a relative (63% vs. 52%). Men who were victims of emotional mistreatment were more likely to be dependent on the perpetrator (29% vs. 10%) than female victims.

Four key differences were found by gender of the victim of incidents of physical mistreatment. Perpetrators of physical mistreatment against men were more likely to be unemployed (67% vs. 31%) and to have had a history of legal problems (76% vs. 35%) compared to perpetrators of physical mistreatment against women. Women victims of physical mistreatment were more likely than men to live with the perpetrator (80% vs. 47%) and to be perpetrated against by a relative (84% vs. 41%).

As stated above, given the low number of male victims of sexual mistreatment, gender differences were not examined for this mistreatment type. Previous research suggests that perpetrators of sexual mistreatment of the elderly generally have histories of prior criminal behavior (Jeary, 2005). In the present sample, about one third of the perpetrators had a prior legal history. Interestingly, a majority of sexual mistreatment perpetrators were not related to the victim and did not live with them. This finding clearly indicates the need for future research in this area with larger samples in order to identify and study older adult victims of sexual mistreatment.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations; all data are self-report; a measure of cognitive functioning of the respondent was not included; we did not include individuals who did not have a home phone or who resided in institutions; and sex of the perpetrator was not assessed. Future research should be directed toward examining the relationship between these perpetrator characteristics and health and mental health conditions associated with elder mistreatment.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In comparison to other forms of interpersonal violence, elder mistreatment has received far less empirical investigation (Acierno, 2003), and therefore there is an even greater gap between empirical evidence informing public policy and clinical practice (Lachs & Pillemer, 2004). This gap is also likely influenced by the low number of the incidents that are reported to the authorities. Epidemiologic research, such as the present study, can help to increase awareness of the case characteristics of incidents of elder mistreatment that are not reported. In addition, longitudinal and experimental research designs are needed to demonstrate causality of the candidate risk factors identified in the present cross-sectional study. Research along these lines will provide more accurate and viable targets for intervention and prevention efforts.

The present study yielded several key findings. First, it appears that the profile of a perpetrator of physical mistreatment against an elderly man may be more “deviant” than a perpetrator against an elderly woman, who is more likely to be perpetrated against by someone with whom she lives. Second, in this study many perpetrators against both men and women were reported to be socially isolated. Third, the present data suggests that the incidence of probable substance use problems is likely higher in perpetrators of elder mistreatment than it is in the general population (ranging from 21–56% depending on the form of mistreatment vs. 11% in general population;(Kessler, Foster, Saunders, & Stang, 1995). These findings may help inform gender sensitive screening instruments to better identify, and hopefully prevent, incidents of elder mistreatment. From a societal level, campaigns focused on increasing awareness of elder mistreatment, correlates of elder mistreatment, and common perpetrator characteristics may help to decrease this important public health problem. Programs aimed at increasing social support and coping strategies, and decreasing the incidence of substance use disorders of caregivers of older adults may also be indicated.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported primarily by a grant from the National Institute of Justice (#2007-WG-BX-0009) as well as a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R21AG030667). Dr. Amstadter is supported by NIMH grant MH083469.

Footnotes

No Disclosures to Report

References

- Acierno R. Epidemiological assessment methodology. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Emotional, Physical, Sexual, Neglectful, and Financial Abuse in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Begle AM, Cisler JM, Hernandez MA, Muzzy W, Acierno R. Prevalence and correlates of poor self-rated health in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ca7ef2. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs S, Manthorpe J, Tinker A, Doyle M, Erens B. Mistreatment of older people in the United Kingdom: findings from the first national prevalence study. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect. 2009;21:1–14. doi: 10.1080/08946560802571870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buri H, Daly JM, Hartz AJ, Jogerst GJ. Factors associated with self-reported elder mistreatment in Iowa’s frailest elders. Research on Aging. 2006;28:562–581. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Reay AM, Browne KD. Risk factor characteristics in carers who physically abuse or neglect their elderly dependants. Aging & Mental Health. 2001;5:56–62. doi: 10.1080/13607860020020654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chokkanathan S, Lee AE. Elder mistreatment in urban India: A community based study. Journal of Elderly Abuse and Neglect. 2005;17(2):45–61. doi: 10.1300/j084v17n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Katona C, Fine-Soveri H, Topinková E, Carpenter GI, Livingston G. Indicators of elder abuse: A crossnational comparison of psychiatric morbidity and other determinants in the Ad-HOC Study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(6):489–497. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192498.18316.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garre-Olmo J, PLanas-Pujol X, Lopez-Pousa S, Juvinya D, Vila A, Vilalta-Franch J. Prevalence and risk factors of suspected elder abuse subtypes in people aged 75 and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(5):815–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeary K. Sexual abuse and sexual offending against elderly people: a focus on perpetrators and victims. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology. 2005;16:328–343. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett K. Psychological trauma and physical health: A psychoneuroimmunology approach to etiology of negative health effects and possible interventions. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2009;1(1):35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: educational attainment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1026–1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, Tobin T, Salomon A, Dubois J. Statewide profile of abuse of older women and the criminal justice response: Final report. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lachs M, Pillemer K. Elder abuse. The Lancet. 2004;364(9441):1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, Waite LJ. Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. Journal of Gerontology. 2008;63:S248–S254. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreadie C, O’Keeffe M, Manthorpe J, Tinker A, Doyle M, Hills A, et al. First steps: the UK national prevalence study of the mistreatment and abuse of older people. The Journal of Adult Protection. 2006;8:4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Moon A, Lawson K, Carpiac M, Spaziano E. Elder abuse and neglect among veterans in greater Los Angeles: Prevalence, types, and intervention outcomes. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2006;46:187–204. doi: 10.1300/J083v46n03_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Elder mistreatment: Abuse, neglect, and exploitation in aging America. Panel to review risk and prevalence of elder abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Finkelhor D. The prevalence of elder abuse: A random sample survey. Gerontologist. 1988;28:51–57. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racic M, Kusmuk S, Kozomara L, Debelnogic B, Tepic R. The prevalence of mistreatment among the elderly with mental disorders in primary health care settings. The Journal of Adult Protection. 2006;8:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Reay AMC, Brown KD. Risk factor characteristics in carers who physically abuse or neglect their elderly dependents. Aging and Mental Health. 2001;5:56–62. doi: 10.1080/13607860020020654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledjski EM, Speisman B, Dierker LC. Does number of lifetime traumas explain the relationship between PTSD and chronic medical conditions? Answers from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(4):341–349. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Barrett-Conor E. Sexual assault and physical health: Findings from a population-based study of older adults. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62:838–843. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatara T. The National Elder Abuse Incidence Study: Executive Summary. New York: Human Services Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 3rd edition. Lenexa, Kansas: AAPOR; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MJ, Weiss D, Wolfson D, Lithwick M. Detection and prevalence of abuse of older males: perspectives from family practice. Journal of Elderly Abuse and Neglect. 2007;19:47–60. doi: 10.1300/J084v19n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink T, Fisher BS. Older women living with intimate partner violence. Aging Health. 2007;3(2):257–265. [Google Scholar]