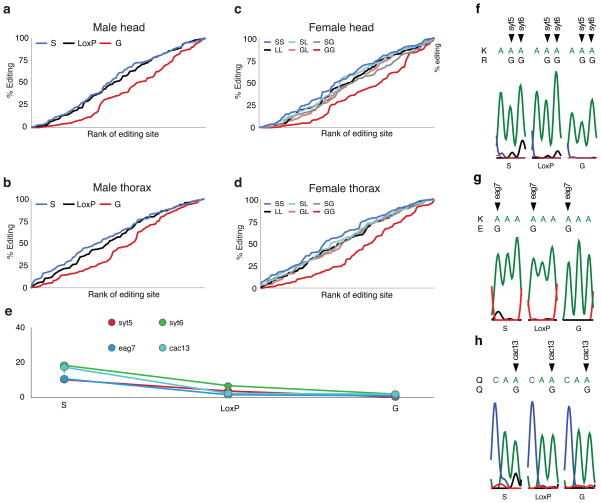

Figure 3. Hard-wiring of dAdar auto-editing modifies the quantitative pattern of RNA editing.

(a–b) Rank-ordered editing levels at 100 adenosines amplified from dAdarS, dAdarWTLoxP and dAdarG male head (a) and thorax tissues (b). Each population is rank-ordered independently to assess the relative abundance of adenosines edited at low, medium and high levels. Note the substantial downward shift in the rank ordering of editing sites amplified from dAdarG tissues compared to both dAdarWTLoxP and dAdarS. (c–d) Rank-ordered editing levels at 100 adenosines amplified from head (c) and thorax (d) tissue of the six female allelic dAdar combinations. Note the substantial downward shift in the rank ordering of editing sites amplified from dAdarG/G tissues compared to all other allelic combinations. (e–h) Editing levels at novel editing sites which were solely or predominantly detected in dAdarS hemi- and homozygotic backgrounds. All of the novel sites were detected at relatively low levels (e). Editing at Synaptotagmin-1 site 5 (syt5) (f) and eag site 7 (eag7) (g) lead to the amino acid substitutions K → R and K → E respectively. RNA editing at synaptotagmin-1 site 6 (syt6) (f) and cacophony site 13 (cac13) (h) result in synonymous changes. Data are derived from n ≥ 3 RT-PCRs for each adenosine. Error bars, s.e.m.