Abstract

Bacterial chemotaxis is an important attribute that aids in establishing symbiosis between rhizobia and their legume hosts. Plant roots and seeds exude a spectrum of molecules into the soil to attract their bacterial symbionts. The alfalfa symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti possesses eight chemoreceptors to sense its environment and mediate chemotaxis toward its host. The methyl accepting chemotaxis protein McpU is one of the more abundant S. meliloti chemoreceptors and an important sensor for the potent attractant proline. We established a dominant role of McpU in sensing molecules exuded by alfalfa seeds. Mass spectrometry analysis determined that a single germinating seed exudes 3.72 nmol of proline, producing a millimolar concentration near the seed surface which can be detected by the chemosensory system of S. meliloti. Complementation analysis of the mcpU deletion strain verified McpU as the key proline sensor. A structure-based homology search identified tandem Cache (calcium channels and chemotaxis receptors) domains in the periplasmic region of McpU. Conserved residues Asp-155 and Asp-182 of the N-terminal Cache domain were determined to be important for proline sensing by evaluating mutant strains in capillary and swim plate assays. Differential scanning fluorimetry revealed interaction of the isolated periplasmic region of McpU (McpU40-284) with proline and the importance of Asp-182 in this interaction. Using isothermal titration calorimetry, we determined that proline binds with a Kd (dissociation constant) of 104 μM to McpU40-284, while binding was abolished when Asp-182 was substituted by Glu. Our results show that McpU is mediating chemotaxis toward host plants by direct proline sensing.

INTRODUCTION

Rapidly changing environmental conditions make soil a challenging environment for bacteria to persist. Motile soil bacteria use chemotaxis to navigate through the soil and to find optimal surroundings for survival. One important group of soil bacteria are symbiotic rhizobia, which fix atmospheric nitrogen to forms utilizable by its host plant. In particular, crop legumes, such as peas, soybeans, and alfalfa, form symbiotic relationships with Rhizobium leguminosarum, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and Sinorhizobium meliloti, respectively (1, 2). Symbiosis partners have evolved a complex and specific molecular dialogue through the exchange of chemical signals, which direct bacterial species to the roots of host plants (3, 4). The rhizosphere is a narrow zone of soil that is influenced by root secretions, while the spermosphere is defined as the zone of soil surrounding a germinating seed. Roots and seeds alike have been shown to exude different types of compounds for the ultimate purposes of successful establishment and proliferation of beneficial microbial communities (5, 6). Host plant exudates recruit symbiotic rhizobia by inducing positive chemotaxis, which allows microbes to accumulate in the rhizosphere (7). Various attractants are exuded from the roots of the S. meliloti host, alfalfa (Medicago sativa), including sugars, amino acids, carboxylic acids, and phenolic compounds (8–12), but knowledge of substances exuded by germinating seeds is greatly lacking (13–18). Information about how S. meliloti perceives seed-derived attractants may aid in symbiotic efficiency, and ultimately greater crop yield by enhancing the recruitment of S. meliloti to the spermosphere of germinating seeds.

Chemotaxis is directed movement based on the perception of chemical stimuli. S. meliloti and other soil bacteria from the Rhizobiaceae family such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and Rhizobium leguminosarum use their chemotactic trait to move toward roots of their host plants, while chemotaxis-compromised strains are outcompeted by wild-type bacteria (19–23). However, little is known about the specific role of individual chemoreceptors in this process. In R. leguminosarum, an mcpC chemoreceptor mutant is severely diminished in nodulation occupancy compared to the wild type (24). To date, there are no studies characterizing the specificity of a rhizobial chemoreceptor for host-derived signals.

Previous work has characterized important aspects of S. meliloti chemotaxis and how it differs from the Escherichia coli paradigm regarding the number and domain topology of chemoreceptors (9), the two-component regulatory system (25–27), and the unidirectional flagellar motor (28–31). Escherichia coli has four conventional chemoreceptors, called methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) and one unorthodox receptor, Aer (32). Aer and the four MCPs share a highly conserved, C-terminal signaling domain that forms a ternary complex with two cytoplasmic chemotaxis proteins, CheA, a histidine kinase, and CheW, an adaptor protein. In the absence of an attractant, CheA is autophosphorylated and subsequently transfers the phosphoryl group to the response regulator protein, CheY (33, 34). Phosphorylated CheY interacts with the cytoplasmic face of the flagellar motor and controls the swimming paths of bacteria (35–37). Orthodox MCPs have an N-terminal periplasmic ligand-binding domain, which have been extensively studied in E. coli, along with each chemoreceptor's repertoire of detected chemotactic stimuli (38–42).

S. meliloti has nine genes coding for putative chemoreceptors (9, 43). We have shown that eight of these receptors participate in chemotaxis, while the mcpS gene is not expressed when cells are motile, and presumably regulates processes other than chemotaxis (9, 44). Seven of the S. meliloti chemoreceptors are classical MCPs, McpT to McpZ, and one receptor, IcpA, lacks the conserved residues that typically serve as methyl-accepting sites to control adaptation. Six of the MCPs are located in the cytoplasmic membrane via two membrane-spanning regions, whereas McpY and IcpA lack such hydrophobic regions (9). All chemoreceptors vary in their ligand-binding domains; however, McpU, McpV, and McpX contain specialized domains such as Cache and TarH signaling domains (9), which are known to bind small molecules such as amino acids (45, 46). McpY possesses two Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domains, which typically sense redox potential, oxygen, or light (47). Deletion of individual receptor genes causes differential impairments in the chemotactic response toward various sugars, amino acids, and organic acids (9). The exact function of S. meliloti chemoreceptors and mode of attractant binding is not known, and the identification of ligands, and in particular, plant-borne signaling molecules, is a focus of our work.

McpU is one of the most strongly expressed chemoreceptors in S. meliloti and is a major sensor for the potent attractant proline (9). We show here that proline is sensed through direct binding to the periplasmic region of McpU. We also demonstrate that McpU mediates positive chemotaxis to host seed exudates and quantify the amount of proline exuded by germinating seeds. In conclusion, sensing of seed-derived proline by McpU plays a significant role in host plant recognition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Derivatives of E. coli K-12 and S. meliloti MV II-1 (48) and the plasmids used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | recA1 endA1 | 78 |

| M15/pREP4 | Kmr; lac ara gal mtlF recA uvr | Qiagen |

| S17-1 | recA endA thi hsdR RP4-2 Tc::Mu::Tn7; Tpr Spr | 56 |

| S. meliloti | ||

| BS182 | Smr; mcpU with codon 182 changed from GAT to GCC (D182A) | This study |

| BS183 | Smr; mcpU-EGFP gene with codon 182 changed from GAT to GCC (D182A) | This study |

| BS184 | Smr; mcpU with codon 155 changed from GAC to GCC (D155A) | This study |

| BS185 | Smr; mcpU-EGFP gene with codon 155 changed from GAC to GCC (D155A) | This study |

| BS187 | Smr; mcpU with codon 182 changed from GAT to GAG (D182E) | This study |

| RU11/001 | Smr; spontaneous streptomycin-resistant wild-type strain | 79 |

| RU11/828 | Smr; ΔmcpU | 9 |

| RU13/149 | Smr; ΔmcpS ΔmcpT ΔmcpU ΔmcpV ΔmcpW ΔmcpX ΔmcpY ΔmcpZ ΔicpA (Δ9) | 26 |

| RU13/285 | Smr; ΔmcpS ΔmcpT ΔmcpV ΔmcpW ΔmcpX ΔmcpY ΔmcpZ ΔicpA (Δ8); mcpU crossed-back into RU13/149 | This study |

| RU13/301 | Smr; mcpU-EGFP gene | 44 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | Cmr Tcr; source of lacIq | 80 |

| pBBR1-MCS2 | Kmr | 81 |

| pBS189 | Apr; lacIq fragment from pBS189 cloned into the SacI site of pBBR1-MCS2 | This study |

| pBS373 | Apr; 735-bp SphI/HindIII PCR fragment containing mcpU, 118 to 852 bp (aa 40 to 284) cloned into pQE30 | This study |

| pBS383 | Apr; 735-bp SphI/HindIII PCR fragment containing mcpU, 118 to 852 bp (aa 40 to 284), with mcpU codon 155 changed from GAC to GCC (D155A) cloned into pQE30 | This study |

| pBS384 | Apr; 735-bp SphI/HindIII PCR fragment containing mcpU, 118 to 852 bp (aa 40 to 284), with mcpU codon 182 changed from GAT to GCC (D182A) cloned into pQE30 | This study |

| pBS390 | Apr; 735-bp SphI/HindIII PCR fragment containing mcpU, 118 to 852 bp (aa 40 to 284), with mcpU codon 182 changed from GAT to GAG (D182E) cloned into pQE30 | This study |

| pBS1053 | 2,124-bp HindIII/XbaI PCR fragment containing mcpU cloned into pBS189 | This study |

| pK18mobsacB | Kmr; lacZ mob sacB | 82 |

| pQE30 | Apr; expression vector | Qiagen |

Media and growth conditions.

E. coli strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) (49) at 37°C. S. meliloti strains were grown in TYC (0.5% [wt/vol] tryptone, 0.3% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.13% CaCl2·6H2O [wt/vol]; pH 7.0) at 30°C (50). Motile cells for capillary assays were grown for 2 days in TYC, diluted 1:2 in 3 ml of TYC, and grown for 11 h. Cultures were then diluted 1:100 in 10 ml of RB minimal medium [6.1 mM K2HPO4, 3.9 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM NaCl, 0.01 mM Na2MoO4, 0.001 mM FeSO4, 20 μg of biotin/liter, 100 μg of thiamine/liter (11)], layered on Bromfield agar plates (27), and incubated at 30°C for 14 h to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.12 ± 0.02. All strains were motile and exhibited swimming characteristics as described by Meier et al. (9). The following antibiotics were used at the indicated final concentrations: for E. coli, ampicillin at 100 μg/ml and kanamycin at 50 μg/ml, and for S. meliloti, neomycin at 120 μg/ml and streptomycin at 600 μg/ml.

Preparation of seed exudates.

The Medicago sativa cultivar “Guardsman II” (registration number CV-203, PI 639220) used in the present study was developed from the extensively studied cultivar “Iroquois” by the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station, New York State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY (48). Seeds (0.1 g, ∼47 ± 1 seeds) were placed in a 50-ml conical tube and washed four times with 35 ml of autoclaved, sterile-filtered water. Next, the seeds were washed once with 3 ml of 6% commercial bleach for 3 min and four times with 35 ml of autoclaved, sterile-filtered water under slow agitation. The seeds were then transferred to a 125-ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 20 ml of autoclaved, sterile-filtered water. The seeds were jostled to distribute them evenly at the bottom of the flask and germinated without shaking at 30°C for 24 h. After incubation, the germination efficiency was ca. 95% as determined by radicle emergence. To harvest the exudate, 19 ml of seed supernatant was removed from the flask, placed into a 50-ml conical tube, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The frozen sample was freeze-dried for 72 h and stored at −20°C. Seed exudates were tested for bacterial contamination by microscopic examination and by plating 20 μl on TYC plates, followed by incubation at 30°C for 24 h. Contaminated samples were not included in the present study.

Quantification of proline in alfalfa seed exudates by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

Seed exudate residue from three biological replicates was thawed to room temperature, resuspended in 1 ml of 0.1% formic acid in water and sonicated for 10 min. The samples were centrifuged at 3,450 × g for 10 min to remove insoluble material. Two 120-μl aliquots were removed from the supernatant of each biological replicate and transferred to separate 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 14,000 × g to pellet remaining insoluble material. A 100-μl aliquot of supernatant was then processed by using an “EZ:faast for Free Physiological Amino Acid Analysis by LC-MS” kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Briefly, EZ:faast consists of a solid-phase extraction step, followed by a derivatization and extraction of free amino acids. The derivatized amino acids were analyzed by LC-MS using the supplied EZ:faast AAA-MS on an Agilent 1100 series HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) coupled with an Applied Biosystems 3200 Q Trap LC-MS/MS System (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA). Calibration solutions were made separately from the Phenomenex kit with l-proline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Proline standard solutions ranging from 55 to 220 nmol/ml were derivatized alongside the exudate samples to establish the proline calibration curve. Using Analyst software (AB Sciex, Concord, Ontario, Canada) for data analysis, the peak area of the internal standard, homoarginine, was used to normalize the concentration of proline and given as average derived from three biological replicates, each processed twice, with duplicate injections.

Swim plate assay.

Swim plates containing RB minimal medium complemented with 10−4 M l-proline, 0.27% Bacto Agar, and various concentrations of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) were inoculated with 3-μl droplets of the test culture, followed by incubation at 30°C for 3 to 4 days (9).

Traditional capillary assays.

Traditional capillary assays were performed essentially as described by Adler (51), with minor modifications (9, 52). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature and suspended in RB minimal medium to an OD600 of 0.1. Closed U-shaped tubes (bent from 65-mm micropipettes; Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA) were placed between two glass plates. For each capillary, 400 μl of bacterial suspension was used to make a bacterial pond. Capillary tubes (1-μl disposable micropipettes; Drummond Microcaps) were sealed at one end and filled with attractant dissolved in RB minimal medium. The capillaries were inserted open end first into the bacterial pond and incubated for 2 h at 22.5°C. Capillaries were removed, the sealed end was cut off, and the complete content was transferred into 1 ml of RB minimal medium. Dilutions were plated in duplicate on TYC plates containing streptomycin. After incubation for 3 days at 30°C, the colonies were counted.

Agarose capillary assays.

Agarose capillary assays were performed essentially as described by Grimm and Harwood (53), with minor modifications. Dried seed exudate was thawed to room temperature, dissolved in acetone-water (7:3 [vol/vol]), and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min. The soluble fraction was concentrated to dryness, dissolved in RB to a concentration of 1.5 mg/ml, and diluted 1:10 in molten 1.1% low-melting-temperature agarose (NuSieve GTG). To fill the capillaries, 0.5-μl capillaries (Drummond Microcaps) with one end sealed were heated with a Bunsen burner, and the open end was placed into the molten mixture. The mixture was allowed to solidify, and the open end of the capillary was placed into a circular chemotaxis chamber formed by a microscope slide, a rubber O-ring with an inner diameter of 8.5 mm and a height of 1 mm (Sarstedt), and a coverslip. Cells were harvested and suspended in RB to an OD600 of 0.20. An 81-μl aliquot of S. meliloti suspension was placed in the chamber before the coverslip was in place. The open end of the capillary was observed at ×100 magnification under dark phase using a Nikon Optiphot-2. Pictures were taken using a Q-Imaging Micropublisher camera.

Hydrogel capillary assays.

Capillaries containing a cross-linked hydrogel instead of agarose were used because of their improved properties in preventing cells from entering the capillaries. The inner glass surfaces of 0.5-μl capillaries (Drummond Microcaps) were cleaned with a 3:1 solution of concentrated sulfuric acid, and 30% hydrogen peroxide before capillaries were treated with a 1% (vol/vol) solution of 3-(trichlorosilyl)propyl methacrylate (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in paraffin oil at room temperature for 10 min. After a thorough rinse with 100% ethanol and removal of residual ethanol in a nitrogen gas stream, the capillaries were baked at 95°C for 10 min. A 10% (wt/vol) solution of poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate with an average Mn of 6,000 (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) was mixed with 10% (wt/vol) Irgacure2959 (Sigma-Aldrich) in 70% ethanol at a ratio of 1:20 to form the hydrogel solution, which was subsequently pulled into the capillaries with a rubber suction bulb. After the capillaries were submerged in hydrogel solution, photopolymerization was performed for 20 s using a 365 nm, 18 W cm−2 OmniCure S1000 UV light source (EXFO Photonic Solutions, Inc., Vanier, Quebec, Canada). Hydrogel capillaries were soaked in distilled H2O for 5 h with five water exchanges and equilibrated with l-proline solutions using the same method. One end of each capillary was sealed with machine grease (Apiezon, Manchester, United Kingdom), and chemotaxis assays were carried out as described for the agarose capillary assays.

DNA methods and genetic manipulations.

S. meliloti DNA was isolated and purified as described previously (27). Plasmid DNA was purified with a Wizard Plus SV Miniprep system (Promega). DNA fragments or PCR products were purified from agarose gels using a Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up system (Promega). PCR amplification of chromosomal DNA was carried out according to published protocols (54). Deletion and codon replacement constructs were created by PCR and overlap extension PCR as described by Higuchi (55). These constructs were cloned into the suicide vector pK18mobsacB, which was then used to transform E. coli S17-1. The plasmid was conjugally transferred to S. meliloti by filter mating according to the method of Simon et al. (56). Allelic replacement was achieved by sequential selections on neomycin and 10% (wt/vol) sucrose as described previously (27). Confirmation of allelic replacement and elimination of the vector was obtained by gene-specific primer PCR and DNA sequencing.

Isolation of S. meliloti cell membranes.

S. meliloti strains BS183, BS185, RU11/001, and RU13/301 (Table 1) were grown in Sinorhizobium motility medium (RB minimal medium, 0.2% mannitol, 2% TY) (11, 57) to an OD600 of 0.26 ± 0.10. A portion (250 ml) of cell culture normalized to an OD600 of 0.26 was harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The cells were suspended in 20 ml of 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)–20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) plus 5 μg of DNase I/ml. After two passages through a French press at 20,000 lb/in2, the resulting extract was freed of unbroken cells by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 2 min. Broken cells were centrifuged at 200,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C, yielding the pellet as the membrane fraction. Membrane fractions were resuspended in 3.5 ml of 1 mM PMSF–20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and homogenized for use in immunoblots. Prior to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-gel electrophoresis, 40-μl portions of the samples were mixed with 25 μl of SDS sample buffer containing 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol. Prior to SDS-electrophoresis, the samples were heated to 100°C for 10 min.

Immunoblotting.

Homogenized membrane fractions were separated in 10% acrylamide gels, transferred to Trans-Blot nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and probed using monoclonal antibodies raised against green fluorescent protein (GFP; Living Colors GFP monoclonal antibody; Clontech, Mountain View, CA) at a 1:20,000 dilution. Blots were incubated with sheep anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-linked whole immunoglobulin (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA) diluted 1:40,000. Detection was achieved by enhanced chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) using Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham, Pittsburgh, PA). Films were scanned by using an Epson Perfection 1640SU and Corel Photo-Paint 10 software. Analysis of the scans was performed using ImageJ and Origin 8.1 software.

Expression and purification of McpU-PR.

The recombinant ligand-binding, periplasmic region of McpU (McpU-PR; McpU40-284) and its single amino acid substitution variants were overproduced from plasmid pBS373, pBS383, pBS384, and pBS390 in E. coli M15/pREP4 (Table 1). Three liters of cell culture were grown to an OD600 of 0.8 at 37°C in LB containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and 50 μg of kanamycin/ml, and gene expression was induced by 0.6 mM IPTG. Cultivation was continued for 4 h at 25°C until harvest. Cells were suspended in 50 ml of column buffer (500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mM NaPO4 [pH 7.0]) and lysed by three passages through a French pressure cell at 20,000 lb/in2 (SLM Aminco, Silver Spring, MD), and the soluble fraction was loaded onto a 5-ml NTA column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) charged with Ni2+. Protein was eluted from the column with elution buffer (500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mM NaPO4 [pH 7.0]). Pooled fractions were concentrated by ultrafiltration on regenerated cellulose membranes (10-kDa cutoff) and further purified by Äktaprime Plus gel filtration HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-300 HR (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The column was equilibrated and developed in 100 mM NaCl–50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) at 0.5 ml/min, and protein-containing fractions were combined and stored at 4°C.

Thermal denaturation studies.

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) experiments were performed using an ABI 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). l-Proline was dissolved in 20 mM imidazole–500 mM NaCl–20 mM NaPO4 (pH 6.4) and used at final concentrations of 100 μM, 1 mM, and 10 mM. McpU-PR (the wild type and its variants) and SYPRO Orange (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) were diluted in the same buffer to final concentrations of 10 μM and a final SYPRO Orange concentration of 0.7× (from a 5,000× stock). Experiments with 30-μl reaction mixtures for all conditions were performed in duplicate. A temperature gradient was applied from 10 to 85°C with a 30-s equilibration at each half degree centigrade. Fluorescence was quantified using the preset FRET parameters (excitation, 490 nm; emission, 530 nm) and normalized to the lowest and highest intensities for each data set. Melting temperatures were determined by data analysis with XLfit from IDBusiness Solutions (Guildford, United Kingdom).

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC).

McpU-PR and McpU-PR/D182E in 100 mM NaCl–50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) were concentrated to 812 μM using a 10-kDa regenerated cellulose membrane in a 50-ml Amicon filter unit and a 10-kDa Centricon centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Measurements were made on a VP-ITC microcalorimeter (MicroCal, Northampton, MA) at 22°C. The protein was placed in the sample cell and titrated with 10-μl injections of 9.8 mM l-proline that had been dissolved in the flowthrough of the protein filtration step. The flowthrough fraction was titrated with the same concentration of l-proline to produce a baseline that was subtracted from the protein titration. The data analysis was carried out using the “one binding site” model of the MicroCal version of Origin 8.1 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

RESULTS

McpU mediates S. meliloti chemotaxis toward seed exudate of its host Medicago sativa.

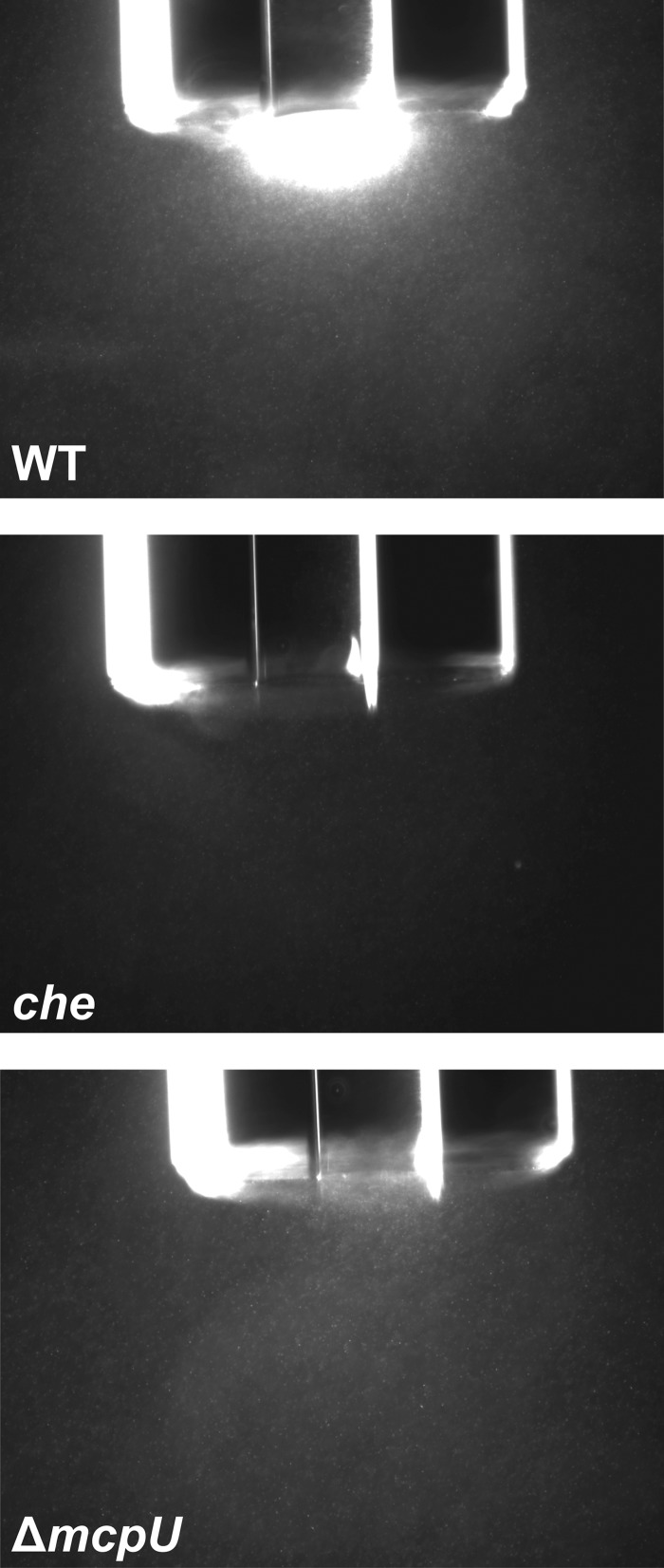

Chemotaxis of rhizobacteria in the soil toward host plant roots is important in establishing symbiosis (58, 59). Since McpU is a major receptor in S. meliloti chemotaxis (9, 44), we analyzed the reaction of the wild type (WT; RU11/001), a strain lacking mcpU (ΔmcpU; RU11/828), and a che strain (ΔmcpS ΔmcpT ΔmcpU ΔmcpV ΔmcpW ΔmcpX ΔmcpY ΔmcpZ ΔicpA [Δ9]; RU13/149) toward exudates of Medicago sativa (alfalfa) seeds. Exudates were prepared from surface-sterilized germinating seeds and tested with motile cell populations in qualitative agarose capillary assays. The wild-type strain revealed a strong positive response toward seed exudate as detected by the accumulation of cells at the mouth of the capillary (Fig. 1, top), while a strain lacking all nine chemoreceptors genes (RU13/149) showed a complete lack of cell accumulation and is therefore defined as chemotaxis negative (che; Fig. 1, middle). In comparison, the mcpU deletion strain exhibited a very weak, but still visible response, observed as the faint accumulation of cells at the capillary opening (Fig. 1, bottom). The strongly diminished response of the ΔmcpU strain indicates that McpU is a principal chemoreceptor for attractant components in alfalfa seed exudates.

FIG 1.

Chemotactic responses of S. meliloti wild type (WT, RU11/001), mcpU deletion (ΔmcpU, RU11/828) and che strain (RU13/149, ΔmcpS ΔmcpT ΔmcpU ΔmcpV ΔmcpW ΔmcpX ΔmcpY ΔmcpZ ΔicpA [Δ9]) toward alfalfa seed exudate. Strains from the early log phase in RB were tested with agarose capillaries containing 0.15 mg of alfalfa seed exudate/ml in RB solidified with 1% agarose. Photographs were taken at ×100 magnification under dark-field microscopy after 10 min for the wild type and after 20 min for the mcpU and che deletion strains, respectively.

The potent chemoattractant proline is exuded by germinating alfalfa seeds.

Since capillary assays revealed that McpU is an important chemoreceptor for host seed exudates and previous studies recognized McpU as a major proline sensor (9), we analyzed the amount of proline exuded by germinating alfalfa seeds. Three biological replicates of surface-sterilized seeds were germinated, and exudates were harvested and processed with the Phenomenex EZ:faast kit. The data analysis after LC-MS revealed that 1.75 ± 0.24 μmol of proline are exuded by 1 g of seeds (201 μg/g of seed), which equals an amount of 3.72 nmol of proline per alfalfa seed. With an average seed volume of 2.17 μl, the concentration of exuded proline at the seed surface is predicted to be 1.71 mM, which would then be allowed to diffuse from the seed into the spermosphere. Millimolar concentrations of proline have been reported to elicit an attractant response from S. meliloti (9, 11). In conclusion, proline is secreted by germinating alfalfa seeds in concentrations detectable by the chemotaxis system of S. meliloti.

McpU mediates chemotaxis of S. meliloti toward proline.

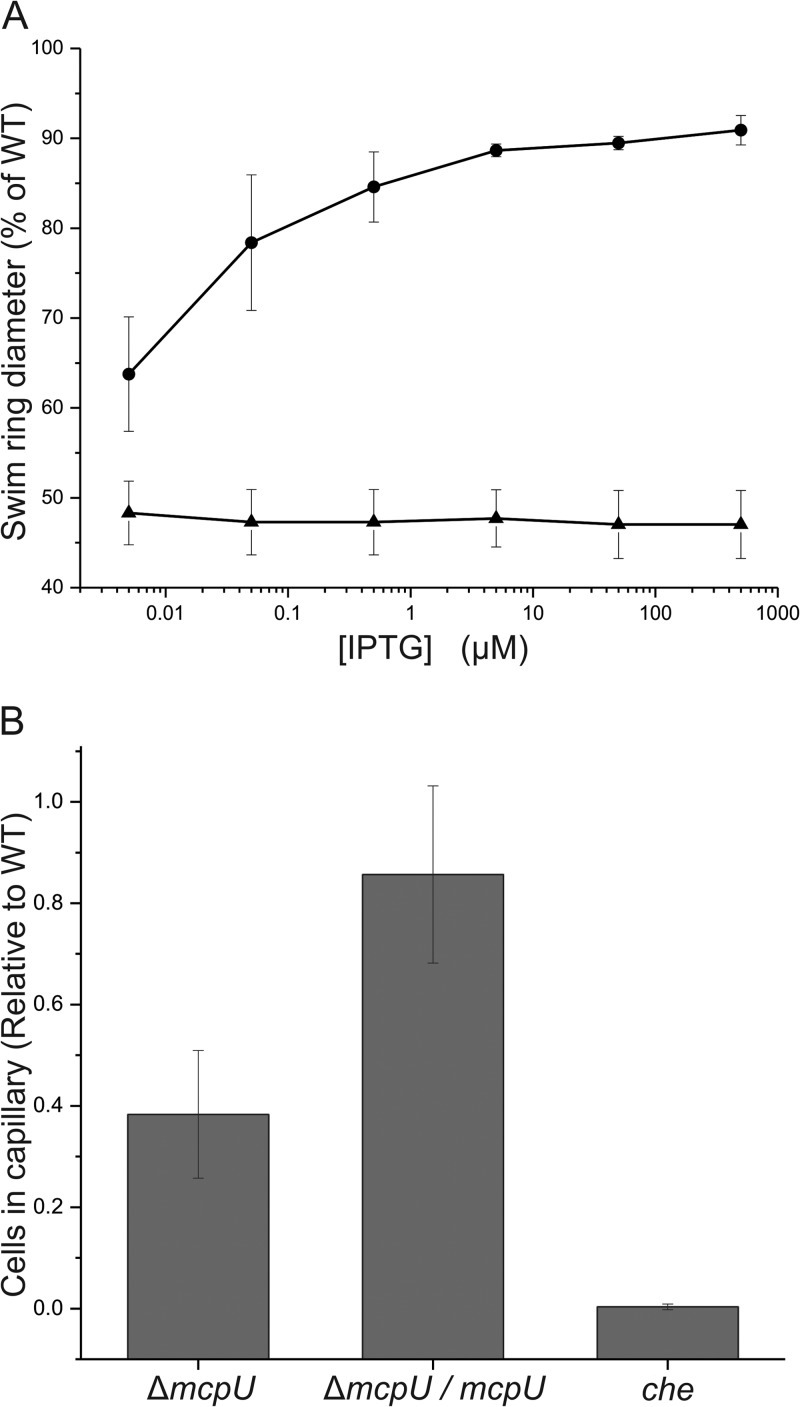

In a previous study, we analyzed the chemotaxis behavior of single chemoreceptor deletion strains and identified McpU as a major receptor for the strong attractant proline (9). To further assess the importance of McpU for the attraction of S. meliloti to proline, we constructed the broad-host-range plasmid pBS1053, which allows controlled expression of mcpU from an inducible lac promoter by the addition of various concentrations of IPTG. We first performed a quantitative swim plate assay with 10−4 M proline (l-proline was used in all studies) as the sole carbon source. After 5 days of incubation at 30°C, the wild type formed a swim ring with a diameter of 80 mm, while the swim ring produced by the mcpU deletion strain was 47% of the wild-type swim ring (Fig. 2A). In comparison, a che strain formed a ring on proline swim plates, which had a diameter of 27% of the wild-type swim ring size (9). In the absence of the inducer IPTG, the complemented strain (ΔmcpU/mcpU) formed a ring larger than that of the deletion strain (64% of the wild type). The observed partial complementation demonstrates that McpU is already expressed under these conditions, which can be explained by basal leakiness of the E. coli lac promoter/LacIq repressor system. The swim ring size of the complemented strain increased with increasing ITPG concentration, reaching a plateau between 5 and 500 μM ITPG with a maximum of 91% of the wild-type swim ring at 500 μM IPTG (Fig. 2). Higher concentrations of IPTG had a marginally inhibitory effect on swim ring size (data not shown). To serve as a second assessment, we quantified the response of S. meliloti strains to proline in a traditional capillary assay. This test is considered the gold standard of chemotaxis assays because of its ability to quantify cell numbers in a capillary, thus allowing for accurate classification of tested chemicals. When the response of wild-type cells to 10 mM proline was tested, 1.1 × 106 cells accumulated in the 1-μl capillary after 2 h of incubation at room temperature. The che strain exhibited a negligible response compared to the wild type, while the response of the mcpU deletion strain was 38% of the wild-type response (Fig. 2B). When the complemented strain was grown in the presence of 500 μM IPTG, which caused optimal recovery of proline sensing on swim plates (Fig. 2A), it attained 86% of the wild-type response (Fig. 3B). Taken together, both assays provided consistent results showing that the response of S. meliloti to proline is greatly dependent on McpU. Furthermore, proline taxis can be restored by the expression of mcpU in trans.

FIG 2.

Complementation of the chemotactic response of the S. meliloti mcpU deletion strain to proline. (A) Quantitative proline swim plate assay with increasing amounts of IPTG. Strains RU11/828 (▲) and RU11/828 with pBS1053 (●) were pipetted onto RB plates containing 10−4 M proline with various concentrations of IPTG to induce expression of mcpU under the control of the lac promoter from plasmid pBS1053. The percentages of the wild-type swim diameter on 0.27% agar are the means of three replicates, each performed in duplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviations from the mean. (B) Quantitative capillary assay of the mcpU deletion strain (ΔmcpU, RU11/828), the complemented strain (ΔmcpU/mcpU, RU11/828 with pBS1053) induced with 500 μM IPTG, and the chemotaxis-negative strain (che, RU13/149) with 10 mM proline. The results for each strain are the means of three experiments, each in triplicate. The means of each strain were normalized to the number of wild-type cells per capillary. Error bars represent the standard deviations from the mean.

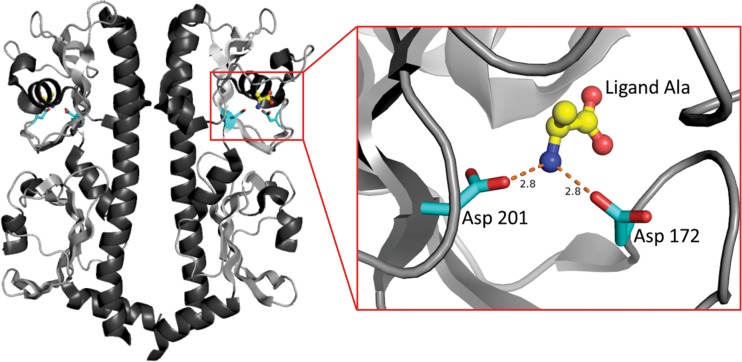

FIG 3.

Identification of McpU residues involved in proline sensing using the structure of the Vibrio cholerae McpN as a model. The structure of the periplasmic amino-terminal domain of the McpN dimer (Protein Data Bank code 3C8C) is oriented to display the tandem Cache domains of V. cholerae McpN. The view on the right provides a close up of the alanine ligand in the binding pocket of the N-terminal Cache domain on the monomer on the right. Two aspartate residues (Asp172 and Asp201) likely coordinate the ligand. The corresponding residues in S. meliloti McpU, Asp155 and Asp182, were chosen for further studies.

A structure-based homology search identifies the ligand-binding site in McpU.

The periplasmic region of McpU contains a conserved Cache (calcium channels and chemotaxis receptors; [45]) signaling domain (amino acid residues 149 to 226; [60, 61]) and a less well-conserved TarH domain (residues 106 to 144; [61]). Members of the Cache family are widespread in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms and are predicted to bind small molecules, including amino acids (45). A homologue search in the RCSB Protein Data Bank revealed that the periplasmic region of McpU (McpU-PR, residues 40 to 284) shares the greatest sequence identity (26%) with the sensor domain of McpN from Vibrio cholerae. The structure of the McpN sensor domain (residues 61 to 300, Protein Data Bank code 3C8C) appears as a homodimer (Fig. 3). Each polypeptide chain has an N-proximal α-helix that loops over into two consecutive Cache domains. Zooming in on either of the N-proximal Cache domains (close up in Fig. 3) reveals the ligand alanine in the binding pocket formed by the domains. The carboxyl groups of two aspartate residues, Asp-172 and Asp-201, coordinate the ligand via hydrogen bonds between the oxygen atoms and the amino group of the ligand. Alignment of McpU-PR and McpN-PR revealed a 34% identity in the region of the McpN tandem Cache domains, whereas the regions outside the tandem cache domains have only 16% identity (62), corroborating the presence of tandem Cache domains in McpU-PR. The amino acid sequence of the McpU periplasmic region was submitted for three dimensional-structure-based homology modeling in the SWISS-MODEL Workspace (63). A model was constructed with McpU-PR residues 7 to 245 based on the McpN template (3C8C) of V. cholerae. When the homology model of McpU-PR was superimposed with the structure of the McpN sensor domain, two aspartate residues, namely, Asp-155 and Asp-182, were conserved in the same positions as the two ligand-coordinating residues in McpN. This finding allows the prediction that the ligand binding pocket of V. cholerae McpN and S. meliloti McpU is conserved and that McpU coordinates proline in a similar manner that McpN uses to bind the ligand alanine.

Single-point mutations in the ligand-binding pocket of McpU cause a diminished chemotaxis response to proline.

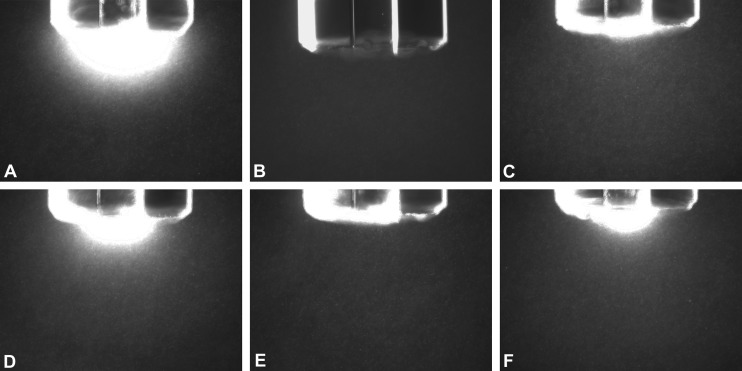

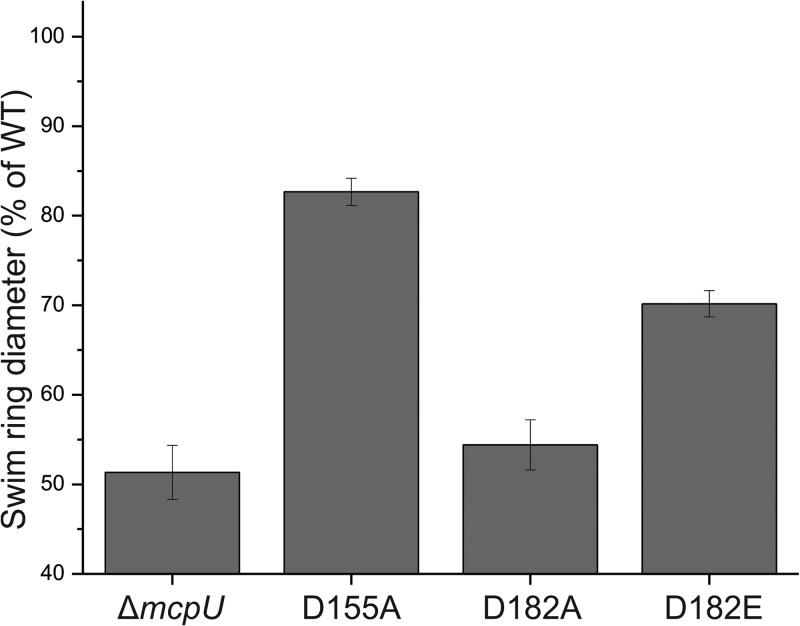

Homology modeling predicted two conserved aspartate residues in McpU-PR to be involved in ligand sensing. To elucidate the role of these residues in chemotaxis toward proline, we created S. meliloti mutants carrying single point mutations in position 155 and 182. Initially, we made alanine substitutions and analyzed the behavior of the resulting mutants in comparison to appropriate control strains in hydrogel capillary assays. The hydrogel capillary assay is an improved variation of the agarose capillary assay used earlier (Fig. 1). Wild-type cells (RU11/001) strongly accumulated around the mouth of the capillary filled with 1 mM proline (Fig. 4A), whereas the che (RU13/149) and the mcpU deletion (RU11/828) strains displayed no or a strongly reduced response to proline, respectively (Fig. 4B and C). Strain BS184 (McpUD155A) exhibited a weaker response compared to the wild type, yet considerably stronger than that of the mcpU deletion strain (RU11/828) (Fig. 4D). In contrast, the response of strain BS182 (McpUD182A) to proline was almost abolished (Fig. 4E). Therefore, we introduced a glutamate residue in position 182, which we predicted to be a less detrimental substitution. The resulting strain, BS187 (McpUD182E) exhibited an intermediary response (Fig. 4F), which was weaker than the wild type but stronger than the mcpU deletion strain. To quantify the importance of aspartate residues 155 and 182 for proline taxis, we performed proline swim plate assays with the mutant strains and compared their behavior to the wild type (Fig. 5). All mutant strains exhibited a diminished response to proline, with the order of response ranking as ΔmcpU < McpUD182A < McpUD182E < McpUD155A < wild type, correlating with the results obtained from the hydrogel capillary assays.

FIG 4.

Chemotactic responses of S. meliloti mcpU mutant strains toward proline in hydrogel capillaries. (A) Wild type (RU11/001); (B) che deletion strain (RU13/149); (C) ΔmcpU strain (RU11/828); (D) McpUD155A strain (BS184); (E) McpUD182A strain (BS182); (F) McpUD182E strain (BS187). Strains from early log phase in RB were tested with hydrogel capillaries containing 1 mM proline. Photographs were taken at ×100 magnification under dark-field microscopy after 20 min.

FIG 5.

Chemotactic responses of S. meliloti mcpU mutant strains toward proline in a quantitative swim plate assay compared to the wild-type strain. The mcpU deletion strain (ΔmcpU, RU11/828), McpUD155A (D155A, BS184), McpUD182A (D182A, BS182), and McpUD182E (D182E, BS187) strains were pipetted onto RB plates containing 10−4 M proline. The percentages of the wild-type swim diameter on 0.27% agar are the means of three replicates, each performed in duplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviations from the mean.

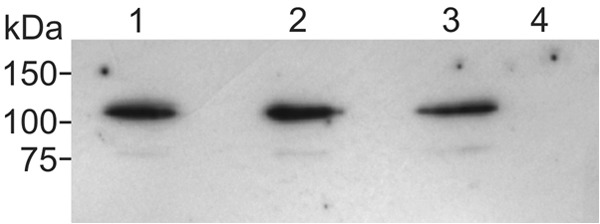

To verify that the altered chemotactic responses of the mutant strains are not caused by reduced levels of mutant McpU protein, we assessed the expression of McpU variant proteins in S. meliloti using immunoblots. Since antibodies directly targeting McpU were not available, we created mutants strains with corresponding variants of McpU-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in its native chromosomal locus for McpUD155A and McpUD182A (Table 1) and compared their expression and incorporation in S. meliloti cell membranes with that of McpU-EGFP (44) using a commercially available monoclonal anti-GFP antibody. Full-length McpU-EGFP fusion variant proteins (101 kDa) were present in isolated membranes at similar levels compared to wild-type McpU-EGFP (Fig. 6). Band intensities from three independent blots quantified as 114 and 91% for McpUD155A-EGFP and McpUD182A-EGFP, respectively, compared to McpU-EGFP. Since there is no correlation between the attractant response of the mutant strains (Fig. 4) and the respective band intensities of variant protein (Fig. 6), we concluded that both aspartate residues in McpU-PR are involved in proline sensing, with Asp-182 being more important than Asp-155.

FIG 6.

Immunoblot analysis of McpU and McpU-variant EGFP fusions in S. meliloti membrane fractions. S. meliloti cells were fractionated, and equal volumes of membrane fractions were electrophoretically separated, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and detected with anti-GFP monoclonal antibody. Lane 1, BS183 (McpUD182A-EGFP); lane 2, RU13/301 (McpU-EGFP); lane 3, BS185 (McpUD155A-EGFP); lane 4, RU11/001 (WT).

Proline interacts with the periplasmic region of McpU involving Asp-182.

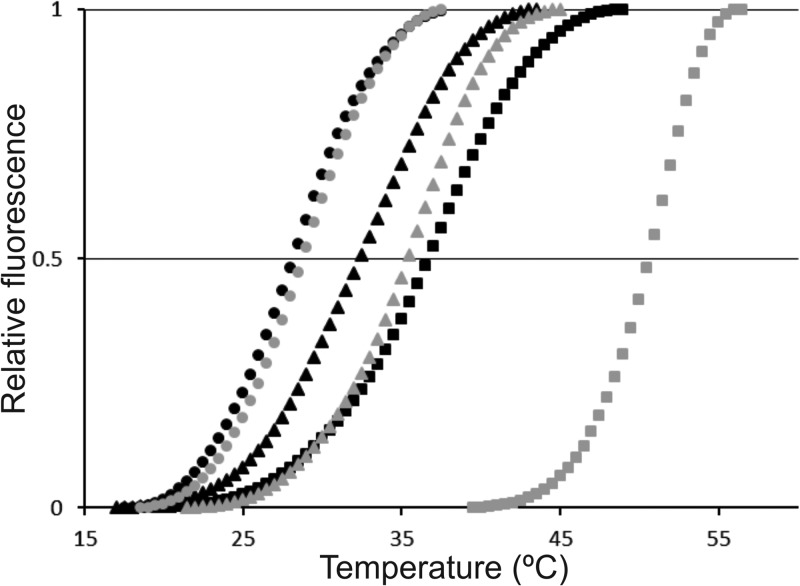

To test the interaction of proline with the isolated sensing domain in vitro, we overexpressed and purified McpU-PR and its single amino acid variants McpU-PRD182A and McpUD182E fused N-terminally to a His6 tag using affinity and size exclusion chromatography. Next, we monitored the thermal unfolding of isolated proteins in the presence of the fluorescent dye SYPRO orange, which binds to the hydrophobic parts of proteins as they unfold. This technique, named differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF), enables the identification of ligands that bind and stabilize purified proteins (64). Characteristically, the transition midpoint, Tm, shifts to higher temperatures upon binding of a low-molecular weight ligand. We determined the Tm of McpU-PR as 37°C, which shifted upon addition of 10 mM proline to 52°C (Fig. 7). The drastic Tm increase of McpU-PR in the presence of proline indicates that it stabilizes the protein through direct interaction. Furthermore, we observed a promotion of McpU-PR stability at lower concentrations of proline (1.0 and 0.1 mM; data not shown). When we tested the protein variants, we found that McpU-PRD182A has a Tm of 29°C, which is 8°C lower than that of McpU-PR, indicative of reduced protein stability. In the presence of proline, no change in Tm was observed, demonstrating lack of interaction. For McpU-PRD182E, the Tm in the absence of proline was 34°C, which only marginally increased by 2 to 36°C. Although the general stability of McpU-PRD182E appears to be comparable to the wild-type protein, the small increase of Tm in the presence of proline infers a relatively weak interaction. Altogether, proline directly interacts with the sensing domain of McpU, while mutations in the binding pocket that affect ligand coordination reduce the affinity between receptor and proline.

FIG 7.

DSF profiles for binding of proline to McpU-PR and McpU-PR variants. Protein stability was monitored as a function of fluorescence intensity. Proteins were tested at a concentration of 10 μM with or without 10 mM proline. McpU-PR (black squares), McpU-PR with proline (gray squares), McpU-PRD182A (black circles), McpU-PRD182A with proline (gray circles) McpU-PRD182E (black triangles), and McpU-PRD182E with proline (gray triangles).

Proline binds directly to McpU-PR.

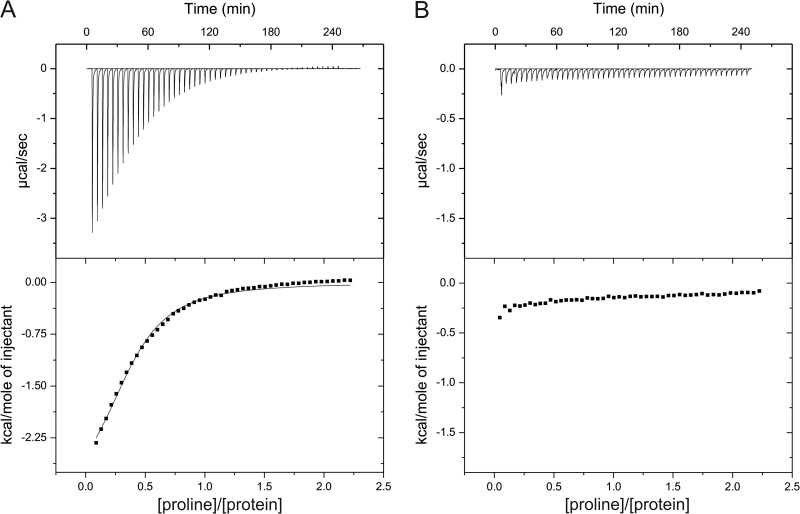

Next, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to quantitatively assess binding of proline to the sensing domain of McpU and its binding site variant (McpU-PRD182E). As shown in Fig. 8A, titration of McpU-PR with proline resulted in large exothermic heat signals that dissipate into heats of dilution. The affinity derived from the binding curve yielded a Kd (dissociation constant) of 104 μM, a value well within the range of reported bacterial chemoreceptor-ligand interactions (65–67). Titration of the McpU-PRD182E variant caused very small exothermic heat signals and earlier saturation of heat release (Fig. 8B). Due to the extremely weak interaction, a Kd was not derived. The ITC results confirm direct binding of proline to McpU and the importance of Asp-182 for ligand binding.

FIG 8.

ITC of McpU-PR and McpU-PRD182E with proline. Titration of McpU-PR (A) and McpU-PRD182E (B) was carried out at a protein concentration of 812 μM with 10-μl injections of 9.8 mM proline. Reference data were produced by titrating buffer with proline and subtracting the resulting heat of ligand dilution from the experimental curves shown. Upper panels show the raw titration data, and lower panels show the normalized and dilution corrected peak areas of the raw titration data. The data were fitted with the One-Set-of-Sites model of the MicroCal version of Origin7.

DISCUSSION

The symbiotic soil bacterium S. meliloti uses chemotaxis to optimize movements toward nutrients and host plant-secreted attractants (9–13). This early step in host interaction allows bacteria to effectively locate infection sites along emerging roots and therefore more effectively compete for nodulation (19, 58). Alfalfa roots release a spectrum of phytochemicals in the soil, including carbohydrates, amino acids, organic acids, fatty acids, sterols, growth factors, vitamins, and flavonoids, to initiate and modulate the dialogue with its microbial symbiont (14, 68, 69). Similarly, germinating seeds exude many organic compounds, and we have shown that alfalfa seed exudates elicit a prevailing chemotactic response from S. meliloti (Fig. 1). An early recruitment of the microbial symbiont to the growing root, e.g., during seed germination, appears to be a plausible strategy to maximize interaction. Although flavonoids have been suggested as host-specific attractants, they elicit only a weak chemotactic response (8, 59) and likely have a short diffusion range in aqueous soil due to their hydrophobic nature. Therefore, amino acids, organic acids, and sugars are more attractive candidates to function as recruiting agents, because they are hydrophilic, and many of these substances have been shown to serve as chemoattractants for S. meliloti (9, 11, 12).

In the present study, we rationally related proline exudation by germinating alfalfa seeds with S. meliloti chemotaxis toward proline. We found that proline is exuded from germinating alfalfa seeds in millimolar concentrations. It is known that plants exude most proteinogenic amino acids into the soil, where they can serve as biological sources of carbon and nitrogen for soil bacteria (70). In addition, certain amino acids, including proline and glutamate, function as osmoprotectants and are accumulated by a variety of bacteria during osmotic stress. This ability is particularly valuable in environments that are prone to significant variation in solute concentration, such as the rhizosphere (70, 71). Therefore, it is beneficial for microbes to seek higher concentrations of proline in the soil, and proline taxis has been reported for several soil bacteria, including Agrobacterium sp. strain H13-3, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and S. meliloti (11, 65, 72). Our current work and other studies presented that S. meliloti can sense and migrate toward proline in the micromolar to millimolar range (Fig. 2 and 4) (9, 11). Furthermore, preliminary analyses revealed a greater attraction of S. meliloti to host compared to nonhost legume seed exudates (data not shown). It would be interesting to see whether the capacity of host plants to exude amino acids such as proline has coevolved with the capability of bacterial symbionts to chemotactically react to these substances, thereby increasing symbiotic effectiveness. Studies are on the way to comparatively examine the secretomes of host and nonhost legumes.

Based on previous results, we focused our studies on McpU, one of eight chemoreceptors mediating S. meliloti chemotaxis. McpU is one of the more abundant chemoreceptors in S. meliloti (44), and capillary and swim plate assays of single deletion mutants identified McpU as major receptor for proline (9). We first investigated the reaction of an in-frame mcpU deletion strain toward exudates harvested from germinating alfalfa seeds and established that its chemotaxis response is strongly diminished (Fig. 1). Since proline is exuded in millimolar concentrations by germinating alfalfa seeds and proline elicits a strong chemotactic response of S. meliloti wild type but not the mcpU deletion strain (Fig. 2 and 4), we concluded that McpU is mediating chemotaxis toward host plants through proline sensing. However, proline is likely not the sole chemoattractant. The function of individual S. meliloti chemoreceptors for root colonization or nodulation has not been investigated. It will be interesting to see whether the mcpU deletion strain is impaired in its ability to induce nodule formation. It is worth mentioning that proline chemotaxis is not completely abolished in the ΔmcpU strain, which suggests an overlap in specificity by other chemoreceptors. It has been reported that at least three chemoreceptors in Pseudomonas putida have overlapping specificity for organic acids (14). In fact, S. meliloti McpX and McpY have been identified previously through capillary assays to contribute to proline taxis (9). McpX and McpU both possess Cache domains, which are known to bind small ligands such as amino acids (45), whereas McpY is a cytosolic protein with dual PAS (73) domains (9). Since detailed information about the proline-sensing characteristics of McpX and McpY is lacking, we can only speculate about their involvement in the recognition of plant-derived proline. Proline binding and/or cooperative signaling of receptor homodimers forming mixed trimers-of-dimers are among the possible explanations for the behavior of mcpX and mcpY receptor mutants. Behavioral studies of S. meliloti are hampered by the circumstance that chemoreceptor function appears to depend on the presence of a receptor ensemble (9). A strain bearing only a chromosomal copy of mcpU but lacking all other receptor genes (RU13/285) behaves like a che strain on swim plates and in the agarose capillary assay. In addition, overexpression of mcpU from pBS1053 in a strain lacking all chemoreceptors (RU13/149) failed to restore proline taxis (data not shown). One plausible hypothesis for this behavior is a reduced capability of an individual chemoreceptor to form a signaling cluster (44). This rules out the possibility of analyzing the sensing range of single chemoreceptor species in vivo without the influence of other chemoreceptors.

Bacterial chemoreceptors can bind attractants directly to their periplasmic domains or indirectly through periplasmic substrate-binding proteins (74). Our in vitro binding studies revealed that McpU binds proline directly to its periplasmic region (Fig. 7 and 8). Using ITC we determined the Kd to be 104 μM, which is within the range of Kd values obtained for proline binding to the periplasmic regions of McpC of B. subtilis and McpX of V. cholerae with 14 and 75 μM, respectively (65, 66). It is worth mentioning that McpU exhibited exothermic binding, similar to McpX, while McpC displayed endothermic binding. The structures of their periplasmic domains were modeled after V. cholerae McpN and proposed to have tandem Cache domains. Interestingly, McpC and McpX were shown to bind multiple amino acid ligands (65, 66). It remains to be seen whether similar binding characteristics hold true for McpU and to what extent these putative ligands are exuded by the alfalfa host.

Since no structural data are available for McpU, we used the crystal structure of V. cholerae McpN complexed with alanine to model the ligand binding pocket and identify residues that coordinate proline (Fig. 3). Two conserved residues, Asp-155 and Asp-182 (Asp-172 and Asp-201 in McpN), in the N-terminal Cache domain were predicted to bind the ligand proline and were chosen for further phenotypic analyses. The moderate decrease in proline taxis caused by a mutation of Asp-155 to Ala indicates the involvement of this residue in proline binding. However, the effect is not as detrimental as an Asp-to-Ala mutation in position 182, which abolished proline taxis mediated by McpU and in vitro binding of proline to McpU-PRD182A (Fig. 4, 5, and 7). We hypothesize that a change in the side chain of residue 155 can be relatively promiscuous, while the nature of the residue in position 182 is critical for proper proline binding. This conclusion is supported by the less impaired phenotype of a strain carrying an Asp-to-Glu mutation in position 182, which conserves the carboxyl group of the side chain (Fig. 4 and 5). The carboxyl moiety of the glutamate residue likely allows coordination of the ligand via hydrogen bonds to the amino group of the ligand, and yet the increased length of the side chain possibly reduces the size of the binding pocket, thereby weakening ligand affinity. Reduced affinity of proline to McpU-PRD182E was confirmed by in vitro DSF and ITC binding analyses (Fig. 7 and 8). Additional information delivered by DSF was the moderate decrease in stability of the proteins with a variation in position 182. We found DSF to be a useful technique for monitoring interactions with proline. Although this technique does not provide Kd values, it can be beneficial as a first screen of mutant proteins or potential ligand interactions.

Chemoreceptor proteins vary in their genomic abundance, sequence, and domain topologies throughout the bacterial kingdom (67, 75). The number of MCPs in bacteria that establish pathogenic or symbiotic interactions with plant roots is typically high, e.g., 20 in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (76) and 36 in Bradyrhizobium japonicum (77). In this view, S. meliloti is an ideal model organism to study chemoreception of phytochemicals, because it only has eight receptors directing chemotaxis (9, 43). Four of these receptors have unannotated ligand-binding domains, while the remaining four contain either Cache or PAS domains (9). We showed that the Cache domain in McpU directly binds proline. McpU is the first chemoreceptor in S. meliloti or other rhizobial bacteria for which a host plant-derived ligand was identified. Furthermore, we presented the importance of proline sensing for the recognition of the S. meliloti host alfalfa. Lastly, we drew the conclusion that McpU has a major contribution in host recognition. It will be interesting to decipher the role of the remaining seven chemoreceptor proteins in host recognition, as we continue the search for, possibly unique, host plant-specific attractants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NSF grant MCB-1253234, the Kate and Jeffress Memorial Trust, and start-up funds from Virginia Tech to B.E.S.

We are indebted to Florian Schubot for sharing the ABI 7300 real-time PCR system, technical advice on the DSF, and support with protein modeling. The Virginia Tech Mass Spectrometry Incubator is maintained with funding from the Fralin Life Science Institute of Virginia Tech, as well as NIFA (Hatch grant 228344). We are indebted to the Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences New York State Agricultural Experiment Station for the donation of alfalfa seeds, Mahama Aziz Traore and Bahareh Behkam for help with the preparation of hydrogel capillaries, Veronika Meier for her help in the construction of RU13/285, Emily Koiner for the construction of pBS1053, and Katherine Broadway for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.van Rhijn P, Vanderleyden J. 1995. The Rhizobium-plant symbiosis. Microbiol. Rev. 59:124–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gage DJ. 2004. Infection and invasion of roots by symbiotic, nitrogen-fixing rhizobia during nodulation of temperate legumes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:280–300. 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.280-300.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bais HP, Weir TL, Perry LG, Gilroy S, Vivanco JM. 2006. The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57:233–266. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uren NC. 2007. Types, amounts, and possible functions of compounds released into the rhizosphere by soil-grown plants, p 19–40 In Pinton R, Varanini Z, Nannipiero P. (ed), The rhizosphere: biochemistry and organic substances at the soil-plant interface. CRC Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson EB. 2004. Microbial dynamics and interactions in the spermosphere. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42:271–309. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.121603.131041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berendsen RL, Pieterse CM, Bakker PA. 2012. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 17:478–486. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiltner L. 1904. Über neue Erfahrungen und Probleme auf dem Gebiete der Bodenbakteriologie. Arbeiten der Deutschen Landwirtschaftsgesellschaft 98:59–78 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dharmatilake AJ, Bauer WD. 1992. Chemotaxis of Rhizobium meliloti towards nodulation gene-inducing compounds from alfalfa roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1153–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier VM, Muschler P, Scharf BE. 2007. Functional analysis of nine putative chemoreceptor proteins in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 189:1816–1826. 10.1128/JB.00883-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burg D, Guillaume J, Tailliez R. 1982. Chemotaxis by Rhizobium meliloti. Microbiology 133:162–163 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Götz R, Limmer N, Ober K, Schmitt R. 1982. Motility and chemotaxis in two strains of Rhizobium with complex flagella. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:789–798 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malek W. 1989. Chemotaxis in Rhizobium meliloti strain L5.30. Microbiology 152:611–612 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartwig UA, Joseph CM, Phillips DA. 1991. Flavonoids released naturally from alfalfa seeds enhance growth rate of Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol. 95:797–803. 10.1104/pp.95.3.797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartwig UA, Maxwell CA, Joseph CM, Phillips DA. 1990. Chrysoeriol and luteolin released from alfalfa seeds induce nod genes in Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol. 92:116–122. 10.1104/pp.92.1.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartwig UA, Phillips DA. 1991. Release and modification of nod-gene-inducing flavonoids from alfalfa seeds. Plant Physiol. 95:804–807. 10.1104/pp.95.3.804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips DA, Wery J, Joseph CM, Jones AD, Teuber LR. 1995. Release of flavonoids and betaines from seeds of seven Medicago species. Crop Sci. 35:805–808. 10.2135/cropsci1995.0011183X003500030028x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips DA, Joseph CM, Maxwell CA. 1992. Trigonelline and stachydrine released from alfalfa seeds activate NodD2 protein in Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol. 99:1526–1531. 10.1104/pp.99.4.1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartwig UA, Maxwell CA, Joseph CM, Phillips DA. 1989. Interactions among flavonoid nod gene inducers released from alfalfa seeds and roots. Plant Physiol. 91:1138–1142. 10.1104/pp.91.3.1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulash M, Ames P, Larosiliere RC, Bergman K. 1984. Rhizobia are attracted to localized sites on legume roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:149–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawes MC, Smith LY. 1989. Requirement for chemotaxis in pathogenicity of Agrobacterium tumefaciens on roots of soil-grown pea plants. J. Bacteriol. 171:5668–5671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbour WM, Hattermann DR, Stacey G. 1991. Chemotaxis of Bradyrhizobium japonicum to soybean exudates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2635–2639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller LD, Yost CK, Hynes MF, Alexandre G. 2007. The major chemotaxis gene cluster of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae is essential for competitive nodulation. Mol. Microbiol. 63:348–362. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Althabegoiti MJ, Lopez-Garcia SL, Piccinetti C, Mongiardini EJ, Perez-Gimenez J, Quelas JI, Perticari A, Lodeiro AR. 2008. Strain selection for improvement of Bradyrhizobium japonicum competitiveness for nodulation of soybean. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 282:115–123. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yost CK, Rochepeau P, Hynes MF. 1998. Rhizobium leguminosarum contains a group of genes that appear to code for methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins. Microbiology 144:1945–1956. 10.1099/00221287-144-7-1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dogra G, Purschke FG, Wagner V, Haslbeck M, Kriehuber T, Hughes JG, Van Tassell ML, Gilbert C, Niemeyer M, Ray WK, Helm RF, Scharf BE. 2012. Sinorhizobium meliloti CheA complexed with CheS exhibits enhanced binding to CheY1, resulting in accelerated CheY1 dephosphorylation. J. Bacteriol. 194:1075–1087. 10.1128/JB.06505-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riepl H, Maurer T, Kalbitzer HR, Meier VM, Haslbeck M, Schmitt R, Scharf B. 2008. Interaction of CheY2 and CheY2-P with the cognate CheA kinase in the chemosensory-signaling chain of Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol. Microbiol. 69:1373–1384. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sourjik V, Schmitt R. 1996. Different roles of CheY1 and CheY2 in the chemotaxis of Rhizobium meliloti. Mol. Microbiol. 22:427–436. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.1291489.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scharf B. 2002. Real-time imaging of fluorescent flagellar filaments of Rhizobium lupini H13-3: flagellar rotation and pH-induced polymorphic transitions. J. Bacteriol. 184:5979–5986. 10.1128/JB.184.21.5979-5986.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eggenhofer E, Haslbeck M, Scharf B. 2004. MotE serves as a new chaperone specific for the periplasmic motility protein, MotC, in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol. Microbiol. 52:701–712. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04022.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eggenhofer E, Rachel R, Haslbeck M, Scharf B. 2006. MotD of Sinorhizobium meliloti and related alpha-proteobacteria is the flagellar-hook-length regulator and therefore reassigned as FliK. J. Bacteriol. 188:2144–2153. 10.1128/JB.188.6.2144-2153.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attmannspacher U, Scharf B, Schmitt R. 2005. Control of speed modulation (chemokinesis) in the unidirectional rotary motor of Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol. Microbiol. 56:708–718. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04565.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker MD, Wolanin PM, Stock JB. 2006. Signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis. Bioessays 28:9–22. 10.1002/bies.20343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukat GS, Lee BH, Mottonen JM, Stock AM, Stock JB. 1991. Roles of the highly conserved aspartate and lysine residues in the response regulator of bacterial chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 266:8348–8354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borkovich KA, Kaplan N, Hess JF, Simon MI. 1989. Transmembrane signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis involves ligand-dependent activation of phosphate group transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:1208–1212. 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welch M, Oosawa K, Aizawa S, Eisenbach M. 1993. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of a signal molecule to the flagellar switch of bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:8787–8791. 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scharf BE, Fahrner KA, Turner L, Berg HC. 1998. Control of direction of flagellar rotation in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:201–206. 10.1073/pnas.95.1.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alon U, Camarena L, Surette MG, Aguera y Arcas B, Liu Y, Leibler S, Stock JB. 1998. Response regulator output in bacterial chemotaxis. EMBO J. 17:4238–4248. 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grebe TW, Stock J. 1998. Bacterial chemotaxis: the five sensors of a bacterium. Curr. Biol. 8:R154–R157. 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)00098-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hazelbauer GL. 1988. The bacterial chemosensory system. Can. J. Microbiol. 34:466–474. 10.1139/m88-080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bibikov SI, Biran R, Rudd KE, Parkinson JS. 1997. A signal transducer for aerotaxis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:4075–4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hazelbauer GL, Falke JJ, Parkinson JS. 2008. Bacterial chemoreceptors: high-performance signaling in networked arrays. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33:9–19. 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazelbauer GL, Lai WC. 2010. Bacterial chemoreceptors: providing enhanced features to two-component signaling. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13:124–132. 10.1016/j.mib.2009.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galibert F, Finan TM, Long SR, Pühler A, Abola P, Ampe F, Barloy-Hubler F, Barnett MJ, Becker A, Boistard P, Bothe G, Boutry M, Bowser L, Buhrmester J, Cadieu E, Capela D, Chain P, Cowie A, Davis RW, Dreano S, Federspiel NA, Fisher RF, Gloux S, Godrie T, Goffeau A, Golding B, Gouzy J, Gurjal M, Hernandez-Lucas I, Hong A, Huizar L, Hyman RW, Jones T, Kahn D, Kahn ML, Kalman S, Keating DH, Kiss E, Komp C, Lelaure V, Masuy D, Palm C, Peck MC, Pohl TM, Portetelle D, Purnelle B, Ramsperger U, Surzycki R, Thebault P, Vandenbol M, Vorholter FJ, Weidner S, Wells DH, Wong K, Yeh KC, Batut J. 2001. The composite genome of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Science 293:668–672. 10.1126/science.1060966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meier VM, Scharf BE. 2009. Cellular localization of predicted transmembrane and soluble chemoreceptors in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 191:5724–5733. 10.1128/JB.01286-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anantharaman V, Aravind L. 2000. Cache: a signaling domain common to animal Ca2+-channel subunits and a class of prokaryotic chemotaxis receptors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:535–537. 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01672-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ulrich LE, Zhulin IB. 2005. Four-helix bundle: a ubiquitous sensory module in prokaryotic signal transduction. Bioinformatics 21(Suppl 3):iii45–iii48. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor BL, Zhulin IB. 1999. PAS domains: internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:479–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamberger W. 1979. An Ouchterlony double diffusion study on the interaction between legume lectins and rhizobial cell surface antigens. Arch. Microbiol. 121:83–90. 10.1007/BF00409209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bertani G. 1951. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 62:293–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Platzer J, Sterr W, Hausmann M, Schmitt R. 1997. Three genes of a motility operon and their role in flagellar rotary speed variation in Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 179:6391–6399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adler J. 1973. A method for measuring chemotaxis and use of the method to determine optimum conditions for chemotaxis by Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 74:77–91. 10.1099/00221287-74-1-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Götz R, Schmitt R. 1987. Rhizobium meliloti swims by unidirectional, intermittent rotation of right-handed flagellar helices. J. Bacteriol. 169:3146–3150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimm AC, Harwood CS. 1997. Chemotaxis of Pseudomonas spp. to the polyaromatic hydrocarbon naphthalene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4111–4115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sourjik V, Sterr W, Platzer J, Bos I, Haslbeck M, Schmitt R. 1998. Mapping of 41 chemotaxis, flagellar and motility genes to a single region of the Sinorhizobium meliloti chromosome. Gene 223:283–290. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00160-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higuchi R. 1989. Using PCR to engineer DNA, p 61–70 In Erlich HA. (ed), PCR technology: principles and applications for DNA amplification. Stockton Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon R, O'Connell M, Labes M, Pühler A. 1986. Plasmid vectors for the genetic analysis and manipulation of rhizobia and other gram-negative bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 118:640–659. 10.1016/0076-6879(86)18106-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rotter C, Mühlbacher S, Salamon D, Schmitt R, Scharf B. 2006. Rem, a new transcriptional activator of motility and chemotaxis in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 188:6932–6942. 10.1128/JB.01902-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ames P, Bergman K. 1981. Competitive advantage provided by bacterial motility in the formation of nodules by Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 148:728–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caetano-Anolles G, Wall LG, De Micheli AT, Macchi EM, Bauer WD, Favelukes G. 1988. Role of motility and chemotaxis in efficiency of nodulation by Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol. 86:1228–1235. 10.1104/pp.86.4.1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ulrich LE, Zhulin IB. 2009. The MiST2 database: a comprehensive genomics resource on microbial signal transduction. Nucleic Acids Res. 38(Database issue):D401–D407. 10.1093/nar/gkp940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer EL, Studholme DJ, Yeats C, Eddy SR. 2004. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:D138–D141. 10.1093/nar/gkh121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modeling. Bioinformatics 22:195–201. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M. 2007. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2:2212–2221. 10.1038/nprot.2007.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Glekas GD, Mulhern BJ, Kroc A, Duelfer KA, Lei V, Rao CV, Ordal GW. 2012. The Bacillus subtilis chemoreceptor McpC senses multiple ligands using two discrete mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 287:39412–39418. 10.1074/jbc.M112.413518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishiyama S, Suzuki D, Itoh Y, Suzuki K, Tajima H, Hyakutake A, Homma M, Butler-Wu SM, Camilli A, Kawagishi I. 2012. Mlp24 (McpX) of Vibrio cholerae implicated in pathogenicity functions as a chemoreceptor for multiple amino acids. Infect. Immun. 80:3170–3178. 10.1128/IAI.00039-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lacal J, Alfonso C, Liu X, Parales RE, Morel B, Conejero-Lara F, Rivas G, Duque E, Ramos JL, Krell T. 2010. Identification of a chemoreceptor for tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates: differential chemotactic response toward receptor ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 285:23126–23136. 10.1074/jbc.M110.110403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dakora FD, Joseph CM, Phillips DA. 1993. Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) root exudates contain isoflavonoids in the presence of Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Physiol. 101:819–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lipton DS, Blanchar RW, Blevins DG. 1987. Citrate, malate, and succinate concentration in exudates from P-sufficient and P-stressed Medicago sativa L. seedlings. Plant Physiol. 85:315–317. 10.1104/pp.85.2.315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moe LA. 2013. Amino acids in the rhizosphere: from plants to microbes. Am. J. Bot. 100:1692–1705. 10.3732/ajb.1300033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Csonka LN, Hanson AD. 1991. Prokaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 45:569–606. 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.003033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oku S, Komatsu A, Tajima T, Nakashimada Y, Kato J. 2012. Identification of chemotaxis sensory proteins for amino acids in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 and their involvement in chemotaxis to tomato root exudate and root colonization. Microbes Environ. 27:462–469. 10.1264/jsme2.ME12005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ponting CP, Aravind L. 1997. PAS: a multifunctional domain family comes to light. Curr. Biol. 7:R674–R677. 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00352-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neumann S, Hansen CH, Wingreen NS, Sourjik V. 2010. Differences in signaling by directly and indirectly binding ligands in bacterial chemotaxis. EMBO J. 29:3484–3495. 10.1038/emboj.2010.224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alexander RP, Zhulin IB. 2007. Evolutionary genomics reveals conserved structural determinants of signaling and adaptation in microbial chemoreceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:2885–2890. 10.1073/pnas.0609359104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wood DW, Setubal JC, Kaul R, Monks DE, Kitajima JP, Okura VK, Zhou Y, Chen L, Wood GE, Almeida NF, Jr, Woo L, Chen Y, Paulsen IT, Eisen JA, Karp PD, Bovee D, Chapman P, Clendenning J, Deatherage G, Gillet W, Grant C, Kutyavin T, Levy R, Li MJ, McClelland E, Palmieri A, Raymond C, Rouse G, Saenphimmachak C, Wu Z, Romero P, Gordon D, Zhang S, Yoo H, Tao Y, Biddle P, Jung M, Krespan W, Perry M, Gordon-Kamm B, Liao L, Kim S, Hendrick C, Zhao ZY, Dolan M, Chumley F, Tingey SV, Tomb JF, Gordon MP, Olson MV, Nester EW. 2001. The genome of the natural genetic engineer Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2317–2323. 10.1126/science.1066804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaneko T, Nakamura Y, Sato S, Minamisawa K, Uchiumi T, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Idesawa K, Iriguchi M, Kawashima K, Kohara M, Matsumoto M, Shimpo S, Tsuruoka H, Wada T, Yamada M, Tabata S. 2002. Complete genomic sequence of nitrogen-fixing symbiotic bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. DNA Res. 9:189–197. 10.1093/dnares/9.6.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hanahan D, Meselson M. 1983. Plasmid screening at high colony density. Methods Enzymol. 100:333–342. 10.1016/0076-6879(83)00066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pleier E, Schmitt R. 1991. Expression of two Rhizobium meliloti flagellin genes and their contribution to the complex filament structure. J. Bacteriol. 173:2077–2085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chang AC, Cohen SN. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, II, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jager W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Pühler A. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73. 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bachmann BJ. 1990. Linkage map of Escherichia coli K-12, edition 8. Microbiol. Rev. 54:130–197 (Erratum, 55:191, 1991) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Novick RP, Clowes RC, Cohen SN, Curtiss R, III, Datta N, Falkow S. 1976. Uniform nomenclature for bacterial plasmids: a proposal. Bacteriol. Rev. 40:168–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]