Abstract

Sequencing-based analysis of single circulating tumor cells (CTCs) has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of metastatic cancer and improve clinical care. Technologies exist to enrich, identify, recover, and sequence single cells, but to enable systematic routine analysis of single CTCs from a range of cancer patients, there is a need to establish processes that efficiently integrate these specific operations. Such engineered processes should address challenges associated with the yield and viability of enriched CTCs, the robust identification of candidate single CTCs with minimal degradation of DNA, the bias in whole-genome amplification, and the efficient handling of candidate single CTCs or their amplified DNA products. Advances in methods for single-cell analysis and nanoscale technologies suggest opportunities to overcome these challenges, and could create integrated platforms that perform several of the unit operations together. Ultimately, technologies should be selected or adapted for optimal performance and compatibility in an integrated process.

Keywords: Microfluidics, single-cell sequencing, cancer genomics

Introduction

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are rare tumor cells found in the bloodstreams of cancer patients (~1 per 106 mononuclear cells) and are believed to be responsible for metastasis [1]. Many approaches for enriching CTCs from blood have developed over the past decade [2**]. These technologies have revealed that increased numbers of CTCs indicate poor prognosis for clinical outcome [3–5]. While the counting of CTCs may inform prognosis, further analysis of these cells may greatly advance our understanding of cancer. CTCs represent real-time, non-invasive biopsies of disseminated (or metastatic) cancer that may otherwise be difficult or impossible to access [6**]. Characterization of these cells could also include genomic analysis, pharmacological sensitivities, and assessments of metastatic potential. Such insights could help to elucidate mechanisms underlying metastasis, tumor evolution, heterogeneity, and resistance to therapy, and may inform clinical decision-making [7*].

Advances in sequencing technologies for single cells make genomic and transcriptomic analyses of CTCs tractable in principle, but there are limited examples to date. RNA sequencing of single prostate CTCs has revealed gene expression patterns of prostate cancer [8]. Targeted DNA sequencing of small panels of genes in single CTCs has revealed somatic mutations shared with primary and metastatic lesions [9]. Whole exome sequencing (WES) or whole genome sequencing (WGS) have recently been reported for CTCs [10*] and have also been described for single human primary tumor cells [11*,12]. One technical challenge facing systematic implementation of sequencing-based studies of CTCs is that the timely and efficient recovery of single CTCs at sufficient yields and purities for analysis remains difficult.

For sequencing-based analysis of CTCs, these cells must be enriched from blood, identified and recovered in a secondary enrichment step, and then prepared for sequencing. Here we discuss recent progress in each of the distinct operations that enable sequencing of single CTCs, and identify opportunities to improve the implementation of such processes. We first consider the technologies currently used to study CTCs. We then suggest ways to overcome the hurdles associated with systematic analysis of single CTCs.

Process for sequencing-based analysis of CTCs

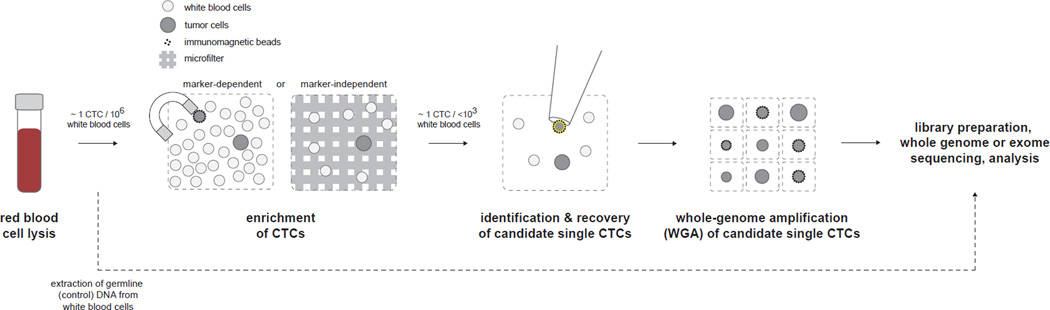

Analysis of CTCs begins with a blood draw (Figure 1). The blood is first depleted of red blood cells and subjected to an enrichment step. Enrichment aims to increase the purity of CTCs from ~1 per 106 mononuclear cells to ~1 per 1000 or fewer mononuclear cells. This increase in purity allows for candidate single CTCs to be identified and recovered. Subsequently, recovered CTCs can be subjected to whole-genome amplification (WGA) in order to generate sufficient quantities of DNA for sequencing-based analysis.

Figure 1.

Process for sequencing-based analysis of single CTCs. A blood draw is obtained and red blood cell (RBC) lysis is performed. Enrichment of CTCs is performed by a marker-dependent or marker-independent method. Candidate single CTCs are then identified and recovered and whole-genome amplification (WGA) is performed. The amplified DNA products are sequenced independently by whole genome or whole exome sequencing. In parallel, genomic DNA extracted from the bulk leukocytes of blood is sequenced to control for germline alterations.

Enrichment of CTCs from blood

There are two major classes of methods to enrich CTCs: ones that rely on the positive identification of known markers such as surface-expressed proteins, and ones that are independent of such markers. Each addresses a shortfall of the other. Marker-dependent methods may miss large tumor cells not expressing the targeted surface-expressed protein, and marker-independent methods may neglect cells clearly expressing tumor markers [13].

Marker-dependent methods typically use differences between the patterns of surface-expressed proteins for cancer and blood cells. These utilize antibodies—often coupled to nano- or microscale magnetic beads, micropatterned surfaces, or fluorophores—to selectively target cell-surface antigens. Examples include CellSearch (Janssen Diagnostics) [14], MagSweeper (Illumina) [8], IsoFlux (Fluxion Biosciences), flow sorting [15,16], and microfluidics systems such as a micromagnetic-microfluidic device [17], “nanovelcro” technology [18], and the posCTC-iChip [19*]. The posCTC-iChip, for instance, uses cell focusing and magnetophoretic separation to enrich immunomagnetically-labeled cells apart from those lacking this label [19*] (Figure 2a). EpCAM is the best characterized surface marker for enriching CTCs, though many of these technologies have been adapted to emphasize other markers such as CD146 or EGFR [15,20].

Figure 2.

Recent progress in methods used in the processing of single CTCs. (A) Schematic of CTC-iChip and demonstration of cell focusing and magnetophoretic sorting. SKBR3 (green, labeled with magnetic beads) and PC3-9 (red, unlabeled) cells are shown (i) after passing through 60 asymmetric focusing units, (ii) after alignment into a single stream, (iii) during magnetic deflection, and (iv) after complete separation. Adapted from [18*]. (B) Capture yields for cell lines expressing different levels of EpCAM when the iChip is operated in positive and negative selection modes. Adapted from [18*]. (C) Bright field and fluorescence images of two CTCs and one white blood cell (WBC) enriched using the Illumina MagSweeper and stained for EpCAM and CD45 expression. Scale bar = 20 microns. Adapted from [8]. (D) Schematic of laser microdissection of a single CTC (CMC = circulating melanoma cell) from the “nanovelcro” chip. Adapted from [17]. (E) Hierarchical clustering of copy number of single CTCs, primary tumor (PT), and metastasis (Met), to assess population substructure. mCTC1 represents the average copy number profile from all CTCs (black, balanced regions; red, underrepresented regions; green, overrepresented regions). Adapted from [9]. (F) Fluorescent micrographs are shown (left) of a white blood cell (WBC), an M229 melanoma cell, and two CTCs (CMC = circulating melanoma cell) from patients. Scale bar = 15 mm. Amplification products from WGA and PCR amplification using a primer for BRAF are shown (center). Sanger sequencing results of each individual cell are presented (right). Adapted from [17].

The realization that not all CTCs may express a known marker of interest [21,22], however, has prompted the development of marker-independent methods. These methods rely upon inherent differences in morphology or size between cancer and blood cells. Examples include density-gradient centrifugation [23], microfiltration [24,25], and microfluidics systems using Dean Flow Fractionation [26] and inertial focusing (i.e. negCTC-iChip [19*]). The CTC-iChip has demonstrated ability to operate in positive (marker-dependent) or negative (marker-independent) selection modes (Figure 2b). In some cases, depletion of cells expressing CD45 (a pan leukocyte marker) is used to enrich for other cell types irrespective of tumor marker expression [27]. The use of both types of technologies in series or in parallel for a given clinical sample should provide the best total enrichment of CTCs, and designed processes should allow incorporation of both methods.

Identification and recovery of candidate single CTCs from enriched sample

The existing technologies for enrichment provide various degrees of purity and total numbers of cells depending on the operation. The contaminating cells are white blood cells that vary in number. Some analytical characterizations of these mixtures can inform the presence and purity of tumor cells; such methods include xenotransplantation [15], PCR for select mutations [28,29], FISH [30,31], intracellular staining [3], or qRT-PCR for expression of cancer-related genes [32–34]. One challenge with these impure samples for genome-scale sequencing, however, is that the degree of purity makes the identification of mutations in the genome difficult. Further purification of these mixtures to single CTCs could overcome this issue. Clearly, the methods used for this secondary purification must maintain the integrity of cells’ DNA in order to be compatible with sequencing.

When marker-based approaches are used for enrichment, immunofluorescence staining [31] can identify live cells likely to be CTCs without impacting the ability to sequence the cells. For epithelial cancers, immunofluorescence staining for EpCAM and absence of CD45—proteins expressed on the surface of epithelial cells and leukocytes, respectively—are often used to identify candidate CTCs (Figure 2c). This approach, however, becomes more challenging when CTCs are enriched by marker-independent approaches. In such cases, methods including intracellular staining [24], FISH [30,31], or cytopathology [35] are commonly relied upon to identify CTCs independent of surface marker expression, but these sacrifice cell viability and may therefore affect the sequencing of such cells. For instance, the use of CellSave Preservative Tubes (Janssen Diagnostics) for fixation reportedly impacts the quality of DNA isolated from single cells [36]. Single CTCs, however, have been successfully sequenced following intracellular staining [10*].

Methods for the recovery of candidate single CTCs include micromanipulation [9], flow cytometry [15], and laser microdissection [18]. The choice of method depends in part on whether the enriched mixture of cells are in suspension, deposited on a surface, or trapped (i.e. in pores of a microfilter). For an enriched mixture of cells in suspension, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) has been used for rapid, single CTC recovery [15], but this technology may be less reliable in recovering rare cells and may reduce yield due to dead volumes or cell aggregation. Alternatively, cells in suspension can be deposited onto a surface for imaging-based identification (Figure 2c) and micromanipulation. Micromanipulation is precise, involves visualization of the cell, and performs a controlled recovery, but can be slow (~30 s – 1 min per cell) and therefore low throughput relative to FACS. For cells bound to solid substrates, such as electrospun PLGA nanofibers in the “nanovelcro” chip [18], laser microdissection has been used to recover candidate single CTCs (Figure 2d).

Whole-genome amplification and sequencing of candidate single CTCs

An average cell contains ~6 pg of DNA. Nanograms of DNA, however, are required for the construction of sequencing libraries. Whole-genome amplification is therefore needed to amplify genomic DNA from 1,000 to 1,000,000-fold. Multiple displacement amplification (MDA) is the most common method for WGA, though other methods have also been developed recently [37]. There are limited examples to date for CTCs amplified by WGA. In one recent study, single CTCs were amplified and analyzed by array CGH for copy number alterations [9] (Figure 2e). In another, single circulating melanoma cells were amplified and subjected to Sanger sequencing of BRAF [18] (Figure 2f). A recent paper reported the variability in success rates of WGA of single CTCs [36]. Single-cell WGS and WES have been performed on WGA products from human primary tumor cells and recently CTCs [10*–12]. Examples of single-cell RNA sequencing of CTCs also exist and these reverse-transcribe RNA into cDNA prior to whole-transcriptome amplification (WTA), library preparation, and sequencing [8]. The overall process flow is similar in principle, with the exception of the reverse transcription and amplification of cDNA as opposed to gDNA.

Process engineering to improve yield and viability of CTCs

Low yield and viability of enriched CTCs are major impediments to routine and systematic analysis of CTCs beyond enumeration. Improvements in these metrics would enable more complete profiling of CTCs on a greater number and diversity of cancer patients at more points in time throughout treatment. High yields of cells could also allow for more assays to be performed in addition to or in parallel with sequencing, depending on compatibility. If healthy CTCs were plentiful after enrichment, for instance, some might be expanded and assayed for drug response or gene expression, while others could be sequenced by WGS or WES to identify somatic alterations.

Current CTC processes enrich only ~ 1 – 100 CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood, and typically examine ~7.5 mL of blood per patient. Blood donations, meanwhile, safely acquire ~ 1 pint (~ 473 mL). If the amount of blood processed for CTCs were increased even to just 30 mL, the yield could be improved 4-fold. Processing of greater amounts of blood could further improve this yield.

Intuition from chemical engineering would suggest a continuous-flow process could enrich CTCs from blood in-line with the circulatory system of a patient. Such perfusion-based enrichment might be analogous to dialysis of blood and permit enrichment of CTCs from the entire volume of blood of a patient (~10 pints). This method might allow for ~600 to 6,000 CTCs to be enriched at any point in time (assuming ~ 1 – 100 CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood), but likely could not involve the addition of enrichment reagents to blood. Further, the half-life of CTCs in blood is reportedly ~24h [31], suggesting that CTCs may be continuously shed from tumors. Integration of enrichment for longer durations might therefore also yield a greater number of CTCs of higher viability and possibly exhibit clinical benefit for the patient. Such perfusion-based enrichment methods, however, would need to be developed and demonstrate clear benefits to guide the treatment of patients in order to gain regulatory approval.

Another way to improve yield may be to couple marker-dependent and marker-independent enrichment methods. For instance, the flow-through of one enrichment method could feed the input to the other. This configuration could enable the capture of CTCs missed by the respective techniques and improve both the yield and diversity enriched. Additionally, expanding the number of markers targeted in marker-dependent enrichment of CTCs could improve yield and diversity. Recent reports have demonstrated enrichment of important subsets of CTCs via a panel of different surface markers [15]. Characterization of RNA or protein expression in cells enriched by marker-independent approaches could lead to new marker discovery for both marker-dependent enrichment and identification.

An artificial way to increase yield would be to expand CTCs by microculture following enrichment. Successful microculture of CTCs, however, is challenging with cell viability only maintaining for short periods of time (< 2 weeks) in vitro. This result could be partly due to the apoptotic state of some CTCs [38,39], but more generally may be related to the challenges of expanding of human primary cells. Recently, new methods have been reported to sustain viability of human primary cells in vitro [40] and these, along with inhibitors of apoptosis, may lead to improved success in the expansion of CTCs. Another option for the expansion of CTCs would be propagation in mice (xenograft models), as previously demonstrated [15]. Xenotransplantation, however, is of low-throughput, low success rate (i.e. tumor initiating capability), and does not permit direct observation of single-cell growth (i.e. selection bias).

Improved recovery of candidate CTCs without compromising sequencing

In the absence of methods to sustain viability of CTCs, recovery (and lysis) should be performed quickly before cells lose viability or undergo apoptosis, resulting in degradation of genomic DNA. This operation could be accomplished by rapid selection and recovery of candidate single CTCs to a reaction chamber or PCR plate for WGA, or simultaneous lysis and WGA of compartmentalized single cells followed by recovery of the WGA products likely to be derived from CTCs. Alternatively, better methods for cell preservation could be explored. Regardless, robust selection of candidate single CTCs or the amplified DNA products derived from candidate single CTCs, respectively, would be needed. After all, one would not want to pay to make libraries (~ $75 / library) and sequence (~ $2000 / 120x WES or 10x WGS) cells that are not CTCs.

When candidate cells need to be selected and recovered, characterization compatible with sequencing must be done prior to WGA, but could also be done post-WGA to build additional confidence in the selection prior to library preparation and WES or WGS. For amplified DNA products, this could be done before and after WGA. For pre-WGA approaches, methods independent of surface marker expression (beyond immunophenotyping of cell surface markers) are needed to identify a more complete repertoire of enriched CTCs. Imaging-based approaches that probe the intracellular environment of live cells could be promising. For instance, molecular beacons could be used to assess RNA expression in live cells [41] (i.e. PSA expression in prostate CTCs [31]), or indicators of altered metabolism in glycolytic tumor cells [42] (i.e. fluorescent glucose analogs or pH indicators) could be examined. Should in vitro viability of CTCs be improved, additional live-cell assays could identify (and functionally characterize) candidate single CTCs. For instance, microengraving in an array of subnanoliter wells could be used to evaluate protein secretion from thousands of single cells over ~1–3 hr timescales [43] (i.e. PSA secretion from prostate CTCs) or image cytometry could be used to assess cell motility and single-cell growth kinetics under hypoxic conditions.

Options exist to characterize post-WGA products prior to construction of libraries for WGS or WES. Polymerase-chain reaction (PCR) followed by Sanger sequencing or quantitative-PCR (qPCR) for single-nucleotide variants would be cheap (< $10 / sample) options. For instance, 90% of pancreatic cancers harbor a KRAS mutation in codons 12 or 13 [44] and this could be probed. Nonetheless, one would not want to perform this for every single cell in the enriched mixture (~1 CTC per 1000 or fewer mononuclear cells). Pre-screening by lack of CD45 expression (a pan leukocyte marker) could help to identify the subset of cells or amplification products worthy of consideration.

Integrating enrichment, isolation, and recovery via nanoscale devices

The steps of the CTC process are currently done separately using different equipment. A seamlessly integrated platform to convert patient blood into sufficient quantities of DNA derived from many candidate single CTCs (of diverse marker expression and morphology) for sequencing would greatly empower systematic CTC analysis.

Nanoscale devices exist for enrichment of CTCs from blood [19*,45,46]; the isolation and characterization of thousands of single cells using an array of nanowells [47]; the sorting, encapsulation, and imaging of single cells within droplet microfluidic devices [48]; and the lysis, WGA, and recovery of amplification products using microfluidics technology either in specified chambers [49–51] or throughout an array of nanowells [52]. Such devices have yet to be coupled, however, for use in an integrated CTC process. Optical nanotweezers [53] may help to link particular steps by controlling precise manipulation of candidate single cells within integrated platforms. This, for instance, allows for placement of cells within specific reaction chambers for lysis and WGA that are connected to external reservoirs, making the recovery of amplification products straightforward.

Ultimately, DNA products need to be recovered to PCR plates for library preparation and sequencing. Library preparation and WES or WGS are quite commonplace nowadays, are amenable to automation by liquid handling systems, and are offered as services by core facilities and service companies. The most important need for systematic CTC analysis, therefore, is the optimization and development of an integrated platform to get to that stage from a single vial of blood. In the end, analytical methods are also needed to accurately interpret the sequencing data, but several options exist [54,55].

Outlook and conclusions

Sequencing-based analysis of single CTCs requires borrowing, innovating, and implementing concepts spanning multiple disciplines of science. Methods to sort, recover, and sequence single cells are not unique to the field of CTCs, and depend on principles extending well beyond biology. Further, the manipulation and study of limited numbers of rare cells is relevant in many contexts of clinical and scientific research, involving samples from fine needle aspirates of tumors to stem cells. Being cognizant of the advances in these areas and how they might apply to unit operations required in the study of CTCs could inform strategies to develop and adapt a process for systematic analysis of CTCs. After all, engineering intuition is needed to make sequencing-based analysis of single CTCs robust, scalable, and applicable to a greater number and diversity of cancer patients. Only then can the full power of CTC sequencing be realized with seamless integration in impactful studies to advance our understanding of cancer.

Highlights.

A process for sequencing single CTCs involves multiple defined operations

Current methods for enrichment fail to capture the entire repertoire of CTCs in blood

Cost of sequencing necessitates the identification and selection of candidate single CTCs without degrading DNA

Whole-genome amplification introduces biases that hinder sensitivity and specificity

Nanoscale technologies could be integrated to improve CTC analysis

Acknowledgements

V.A.A. was supported in part by a graduate fellowship from the National Science Foundation. J.C.L. is a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar. This work was supported in part by Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Glossary

- Circulating tumor cells

Tumor cells found in the bloodstream and believed to be responsible for metastasis

- Metastasis

The spread of cancer from the primary tumor to other sites in the body

- Whole-genome amplification (WGA)

Enzymatic amplification of genomic DNA from a single cell or low amounts of DNA. Multiple displacement amplification is the main method of WGA. This reaction uses isothermal polymerase (e.g. phi 29) to replicate and displace strands that have been primed by random hexamers

- Whole-exome sequencing (WES)

Sequencing libraries are hybrid-selected using probes for exonic DNA (~1% of the genome that codes for proteins). This reduces the amount of sequencing needed to achieve a given target depth, and allows the coding region of the genome to be examined.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

- 1.Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet M, Connelly MC, Rao C, Tibbe AGJ, Uhr JW, Terstappen LWMM. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6897–6904. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu M, Stott S, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. Circulating tumor cells: approaches to isolation and characterization. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:373–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010021. An excellent analysis of detection strategies for CTCs and the range of approaches used for characterization.

- 3.Cristofanilli M, Hayes DF, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Matera J, Allard WJ, Miller MC, et al. Circulating tumor cells: a novel prognostic factor for newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1420–1430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen SJ, Punt CJA, Iannotti N, Saidman BH, Sabbath KD, Gabrail NY, Picus J, Morse M, Mitchell E, Miller MC, et al. Relationship of circulating tumor cells to tumor response, progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3213–3221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bono JS, Scher HI, Montgomery RB, Parker C, Miller MC, Tissing H, Doyle GV, Terstappen LWWM, Pienta KJ, Raghavan D. Circulating tumor cells predict survival benefit from treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6302–6309. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alix-Panabières C, Schwarzenbach H, Pantel K. Circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:199–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062310-094219. A recent review of the two prominent options for non-invasive biopsies of solid cancers: CTCs and circulating tumor DNA.

- 7. Garraway LA. Genomics-driven oncology: framework for an emerging paradigm. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1806–1814. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.8934. This paper describes the discovery, technology, and therapeutic development involved in translating genomic sequencing data into the deployment of targeted cancer therapies.

- 8.Cann GM, Gulzar ZG, Cooper S, Li R, Luo S, Tat M, Stuart S, Schroth G, Srinivas S, Ronaghi M, et al. mRNA-Seq of single prostate cancer circulating tumor cells reveals recapitulation of gene expression and pathways found in prostate cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heitzer E, Auer M, Gasch C, Pichler M, Ulz P, Hoffmann EM, Lax S, Waldispuehl-Geigl J, Mauermann O, Lackner C, et al. Complex tumor genomes inferred from single circulating tumor cells by array-CGH and next-generation sequencing. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2965–2975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ni X, Zhuo M, Su Z, Duan J, Gao Y, Wang Z, et al. Reproducible copy number variation patterns among single circulating tumor cells of lung cancer patients. PNAS. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320659110. This paper presents sequencing of single CTCs.

- 11. Hou Y, Song L, Zhu P, Zhang B, Tao Y, Xu X, Li F, Wu K, Liang J, Shao D, et al. Single-cell exome sequencing and monoclonal evolution of a JAK2-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell. 2012;148:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.028. This paper presents some of the challenges associated with the sequencing of DNA amplified by whole-genome amplification (WGA) from single cells.

- 12.Navin N, Kendall J, Troge J, Andrews P, Rodgers L, McIndoo J, Cook K, Stepansky A, Levy D, Esposito D, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhe X, Cher ML, Bonfil RD. Circulating tumor cells: finding the needle in the haystack. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:740–751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riethdorf S, Fritsche H, Müller V, Rau T, Schindlbeck C, Rack B, Janni W, Coith C, Beck K, Jänicke F, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a validation study of the CellSearch system. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:920–928. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang L, Ridgway LD, Wetzel MD, Ngo J, Yin W, Kumar D, Goodman JC, Groves MD, Marchetti D. The identification and characterization of breast cancer CTCs competent for brain metastasis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:180ra48. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Y, Fan L, Zheng J, Cui R, Liu W, He Y, Li X, Huang S. Detection of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients utilizing multiparameter flow cytometry and assessment of the prognosis of patients in different CTCs levels. Cytometry A. 2010;77:213–219. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang JH, Krause S, Tobin H, Mammoto A, Kanapathipillai M, Ingber DE. A combined micromagnetic-microfluidic device for rapid capture and culture of rare circulating tumor cells. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2175–2181. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40072c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou S, Zhao L, Shen Q, Yu J, Ng C, Kong X, Wu D, Song M, Shi X, Xu X, et al. Polymer nanofiber-embedded microchips for detection, isolation, and molecular analysis of single circulating melanoma cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:3379–3383. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ozkumur E, Shah AM, Ciciliano JC, Emmink BL, Miyamoto DT, Brachtel E, Yu M, Chen PI, Morgan B, Trautwein J, et al. Inertial focusing for tumor antigendependent and -independent sorting of rare circulating tumor cells. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:179ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005616. This paper reports a recent microfluidics technology capable of enriching CTCs via marker-dependent or marker-independent modes.

- 20.Mostert B, Kraan J, Bolt-de Vries J, van der Spoel P, Sieuwerts AM, Schutte M, Timmermans AM, Foekens R, Martens JWM, Gratama J-W, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer may improve through enrichment with anti-CD146. Breast Cancer Res Tr. 2011;127:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0879-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikolajczyk SD, Millar LS, Tsinberg P, Coutts SM, Zomorrodi M, Pham T, Bischoff FZ, Pircher TJ. Detection of EpCAM-negative and cytokeratin-negative circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood. J Oncol. 2011;2011:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2011/252361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng G, Herrler M, Burgess D, Manna E. Enrichment with anti-cytokeratin alone or combined with anti-EpCAM antibodies significantly increases the sensitivity for circulating tumor cell detection in metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R69. doi: 10.1186/bcr2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg R, Gertler R, Friederichs J, Fuehrer K, Dahm M, Phelps R, Thorban S, Nekarda H, Siewert JR. Comparison of two density gradient centrifugation systems for the enrichment of disseminated tumor cells in blood. Cytometry. 2002;49:150–158. doi: 10.1002/cyto.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desitter I, Guerrouahen B. A new device for rapid isolation by size and characterization of rare circulating tumor cells. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:427–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosokawa M, Hayata T, Fukuda Y, Arakaki A, Yoshino T, Tanaka T, Matsunaga T. Size-selective microcavity array for rapid and efficient detection of circulating tumor cells. Anal Chem. 2010;82:6629–6635. doi: 10.1021/ac101222x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou HW, Warkiani ME, Khoo BL, Li ZR, Soo RA, Tan DS-W, Lim W-T, Han J, Bhagat AAS, Lim CT. Isolation and retrieval of circulating tumor cells using centrifugal forces. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1259. doi: 10.1038/srep01259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang L, Lang JC, Balasubramanian P, Jatana KR, Schuller D, Agrawal A, Zborowski M, Chalmers JJ. Optimization of an enrichment process for circulating tumor cells from the blood of head and neck cancer patients through depletion of normal cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;102:521–534. doi: 10.1002/bit.22066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mostert B, Jiang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Wang H, Bolt-de Vries J, Biermann K, Kraan J, Lalmahomed Z, van Galen A, de Weerd V, et al. KRAS and BRAF mutation status in circulating colorectal tumor cells and their correlation with primary and metastatic tumor tissue. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:130–141. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maheswaran S, Sequist LV, Nagrath S, Ulkus L, Brannigan B, Collura CV, Inserra E, Diederichs S, Iafrate AJ, Bell DW, et al. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:366–377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leversha MA, Han J, Asgari Z, Danila DC, Lin O, Gonzalez-Espinoza R, Anand A, Lilja H, Heller G, Fleisher M, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of circulating tumor cells in metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2091–2097. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stott SL, Lee RJ, Nagrath S, Yu M, Miyamoto DT, Ulkus L, Inserra EJ, Ulman M, Springer S, Nakamura Z, et al. Isolation and characterization of circulating tumor cells from patients with localized and metastatic prostate cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:25ra23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smirnov DA. Global gene expression profiling of circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4993–4997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tewes M, Aktas B, Welt A, Mueller S, Hauch S, Kimmig R, Kasimir-Bauer S. Molecular profiling and predictive value of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: an option for monitoring response to breast cancer related therapies. Breast Cancer Res Tr. 2008;115:581–590. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strati A, Markou A, Parisi C, Politaki E, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V, Lianidou E. Gene expression profile of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer by RT-qPCR. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:422. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofman VJ, Ilie MI, Bonnetaud C, Selva E, Long E, Molina T, Vignaud JM, Flejou JF, Lantuejoul S, Piaton E, et al. Cytopathologic detection of circulating tumor cells using the isolation by size of epithelial tumor cell method: promises and pitfalls. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;135:146–156. doi: 10.1309/AJCP9X8OZBEIQVVI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swennenhuis JF, Reumers J, Thys K, Aerssens J, Terstappen LW. Efficiency of whole genome amplification of Single Circulating Tumor Cells enriched by CellSearch and sorted by FACS. Genome Med. 2013;5:106. doi: 10.1186/gm510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zong C, Lu S, Chapman AR, Xie XS. Genome-wide detection of single-nucleotide and copy-number variations of a single human cell. Science. 2012;338:1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1229164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kallergi G, Konstantinidis G, Markomanolaki H, Papadaki MA, Mavroudis D, Stournaras C, Georgoulias V, Agelaki S. Apoptotic circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in early and metastatic breast cancer patients. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1886–1895. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehes G, Witt A, Kubista E, Ambros PF. Circulating breast cancer cells are frequently apoptotic. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:17. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61667-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X, Ory V, Chapman S, Yuan H, Albanese C, Kallakury B, Timofeeva OA, Nealon C, Dakic A, Simic V, et al. ROCK inhibitor and feeder cells induce the conditional reprogramming of epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao G, Rhee WJ, Tsourkas A. Fluorescent probes for live-cell RNA detection. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;11:25–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adalsteinsson VA, Tahirova N, Tallapragada N, Yao X, Campion L, Angelini A, Douce TB, Huang C, Bowman B, Williamson CA, et al. Single cells from human primary colorectal tumors exhibit polyfunctional heterogeneity in secretions of ELR+ CXC chemokines. Integr Biol. 2013;5:1272–1281. doi: 10.1039/c3ib40059j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–1617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stott SL, Hsu C-H, Tsukrov DI, Yu M, Miyamoto DT, Waltman BA, Rothenberg SM, Shah AM, Smas ME, Korir GK, et al. Isolation of circulating tumor cells using a microvortex-generating herringbone-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:18392–18397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012539107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sollier E, Go DE, Che J, Gossett D, O'Byrne S, Weaver WM, Kummer N, Rettig M, Goldman J, Nickols N, et al. Size-selective collection of circulating tumor cells using vortex technology. Lab Chip. 2013 doi: 10.1039/c3lc50689d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Love JC, Ronan JL, Grotenbreg GM, van der Veen AG, Ploegh HL. A microengraving method for rapid selection of single cells producing antigen-specific antibodies. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:703–707. doi: 10.1038/nbt1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen A, Byvank T, Chang W-J, Bharde A, Vieira G, Miller BL, Chalmers JJ, Bashir R, Sooryakumar R. On-chip magnetic separation and encapsulation of cells in droplets. Lab Chip. 2013;13:1172–1181. doi: 10.1039/c2lc41201b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan HC, Wang J, Potanina A, Quake SR. Whole-genome molecular haplotyping of single cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;29:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lecault V, White AK, Singhal A, Hansen CL. Microfluidic single cell analysis: from promise to practice. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blainey PC, Mosier AC, Potanina A, Francis CA, Quake SR. Genome of a low-salinity ammonia-oxidizing archaeon determined by single-cell and metagenomic analysis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gole J, Gore A, Richards A, Chiu Y-J, Fung H-L, Bushman D, Chiang H-I, Chun J, Lo Y-H, Zhang K. Massively parallel polymerase cloning and genome sequencing of single cells using nanoliter microwells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nbt.2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiou PY, Ohta AT, Wu MC. Massively parallel manipulation of single cells and microparticles using optical images : Abstract : Nature. Nature. 2005;436:370–372. doi: 10.1038/nature03831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, Philippakis AA, del Angel G, Rivas MA, Hanna M, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, Gabriel S, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]