Abstract

Background

Low-dose aspirin is widely used for the prevention of cardiovascular events. The prevalence of gastroduodenal injuries and the risk factor profile including gastroprotective drug therapy needs to be clarified in Japanese patients taking daily aspirin for cardioprotection.

Methods

This Management of Aspirin-induced Gastro-Intestinal Complications (MAGIC) study was conducted with a prospective nationwide, multicenter, real-world registry of Japanese patients at high-risk of cardiovascular diseases who were taking regular aspirin (75–325 mg) for 1 month or more. All patients underwent endoscopic examination for detection of gastroduodenal ulcer and mucosal erosion. The risk factor profiles including the concurrent drug therapy were compared for those patients with gastroduodenal problems and those without.

Results

Gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion were detected in 6.5, and 29.2 % of the 1,454 patients receiving aspirin, respectively. H. pylori infection was associated with an increased risk for ulcer: OR 1.83 (1.18–2.88 p = 0.0082). Risk of erosion was lower with enteric-coated aspirin than with buffered aspirin: odds ratio (OR) 0.47 (0.32–0.70, p = 0.0002). Patients receiving proton pump inhibitors had lower risks for both gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion: OR 0.34 (0.15–0.68, p = 0.0050) and 0.32 (0.22–0.46, p < 0.0001), respectively. However, those receiving histamine 2-receptor antagonists had reduced risks for erosion but not for ulcer: OR 0.49 (0.36–0.68, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion are common in Japanese patients taking low dose aspirin for cardioprotection. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the risk of gastroduodenal mucosal injury.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00535-013-0839-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Low-dose aspirin, Gastroduodenal ulcer, Gastroduodenal erosion, Endoscopy, Cardiovascular patients

Introduction

Antiplatelet drug therapy reduces the risk of cardiovascular (CV) diseases in various patient populations. Aspirin use is supported with clinical evidence [1–3], but can cause adverse events, such as gastrointestinal (GI) injuries, even with a low-dose regimen [4]. According to meta-analyses, aspirin therapy increases the risk of GI bleeding by 2.7-fold as compared with results for a control arm, while it reduces the risk of major CV events by approximately 20 % [5]. These complications of GI bleeding are more complex than previously thought. Indeed, the risk of CV events increases in patients who have experienced major bleeding events within a year. Thus, GI bleeding may lead to a higher incidence of subsequent thrombotic events. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends the use of low-dose aspirin (75–325 mg) for patients having a 10-year CV-event risk of 10 % or greater [6]. The US Preventive Services Task Force also recommends prophylactic aspirin therapy to be limited to patients with a 5-year CV risk of 3 % or greater, claiming that prophylaxis may not be beneficial for patients at low CV-event risk because the net clinical benefit is not high enough [7].

A limited amount of data is available for calculating the net clinical benefit in Japanese patients. Although it may not be directly comparable, data of the Western populations have indicated the overall relative risk of upper GI complications was 2.2 to 3.1 times higher in aspirin users than in non-aspirin users [8], whereas the odds ratio (OR) of upper GI bleeding was 5.5 in Japanese aspirin users [9]. The higher risk of GI bleeding in Japanese patients might be due to the higher prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in the elderly and those who smoke tobacco [9, 10].

We conducted the Management of Aspirin-induced Gastrointestinal Complications (MAGIC) study to determine the prevalence of endoscopic gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion in Japanese patients receiving regular aspirin for cardioprotection, and to clarify the risk factor profile including the concurrent use of gastroprotective drugs. This paper reports the baseline data obtained at the entry of this study.

Methods

Study design

This MAGIC study was conducted as an observational study in Japan. The details of the study design were published elsewhere [11]. Described briefly, the study consisted of high-risk CV patients taking low-dose aspirin for cardioprotection that were consecutively recruited from 63 nationwide institutions between April 2007 and September 2009. It was each investigator’s discretion to judge “high risk of CV patients”. Gastroduodenal ulcers and erosions were detected by endoscopy at enrollment. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board in each institution. All participants signed the written informed consent. The present paper reports the baseline data of the enrollment.

Study population

The study population included patients with CV disease taking aspirin (75–330 mg daily) for at least 1 month. It included participants aged 20 years or older, and excluded those with serious hepatic, renal or pulmonary disorders, active cancer, hypersensitivity to aspirin or salicylate derivatives, pregnancy, possible pregnancy or pregnancy being planned, and prior surgical resection of esophagus, stomach, or duodenum.

Baseline demographic information

Upon the study entry, data on each patient’s age, sex, underlying CV disease (e.g., coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and atrial fibrillation), comorbidities (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome), smoking habit, alcohol and coffee consumption, aspirin dosage and formulations (buffered or enteric coated), use of concomitant drugs, and history of upper GI ulcer were collected. All the participants were tested for the presence of H. pylori antibody after signing informed consent. H. pylori antibody in blood sample was measured using Anti-H. pylori IgG assay kit (SRL Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The H. pylori antibody was considered positive if the antibody level was ≥10 U/mL. The information on history of H. pylori eradication was collected from the patient medical records, where the eradication therapy was not well defined. Therefore, the results of eradication therapy were excluded from analysis. Antiulcer drugs included proton pump inhibitors (PPI), histamine 2-receptor antagonists (H2RA), cytoprotective antiulcer drugs, or prostaglandin analog (PGA).

Endoscopic assessment

Gastroduodenal ulcers or erosions were detected by endoscopy and the diagnosis was confirmed by the endoscopic evaluation committee (see Appendix). Gastroduodenal ulcer was defined by a mucosal break of 5 mm or greater in diameter with unequivocal depth, and erosion by mucosal change covered with white necrotic substance of less than 5 mm in diameter. The longer diameter of the lesion was measured as a standard of the length that opened biopsy forceps of 6 mm.

Study organization

The study design was formulated by the Organizing Committee (see Appendix), and data were collected through an Internet-based system.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables between two groups were analyzed with Fisher’s exact test, and the means of unpaired continuous variables, by Welch’s t test. The prevalence and 95 % confidence interval (CI) were estimated by using the binomial distribution. The risk of gastroduodenal ulcer or erosion was estimated by the OR with 95 % CI by using univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. In the multivariate model, the odds ratio was adjusted by suspected risk factors such as age, sex, current tobacco smoking, alcohol use, diabetes mellitus, the presence of H. pylori antibody, and history of peptic ulcer, and uses of enteric-coated aspirin, PPI, H2RA, cytoprotective antiulcer drugs. A p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed by using the software R 2.14.0 (R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Role of the funding source

The sponsor foundation had no role on the study design, selection of study institutions, selection of the committee members, data analyses, or the writing of the manuscript.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the patients

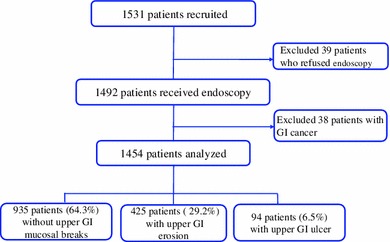

Among 1,531 patients who were consented and enrolled in the present study, 39 patients refused endoscopy and withdrew the consent, and remaining 1,492 patients received endoscopy. Data of 1,454 participants were used for analysis excluding those of 38 patients for gastric cancer, esophageal cancer, or colon cancer (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study patients

The mean participants’ age was 68.1 ± 9.5 years, and 73.5 % of the participants were male. Aspirin was received daily for a mean duration of 4.6 ± 4.4 years (Table 1). A total of 89.4 % received enteric-coated aspirin and 10.6 %, buffered aspirin. The majority of the patients took 100 mg daily of enteric-coated aspirin (92.8 %), and 81 mg daily of buffered aspirin (96.2 %). Other NSAIDs were concomitantly used in only 6.5 %.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Total (n = 1454) |

AMB (n = 935) (64.3 %) |

Erosion (n = 425) (29.2 %) |

p valuea | Ulcer n = 94 (6.5 %) |

p valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 68.1 ± 9.5 | 68.8 ± 9.5 | 67.3 ± 9.3 | 0.0060 | 65.1 ± 10.2 | 0.0009 |

| Men (%) | 1068 (73.5) | 669 (71.6) | 320 (75.3) | 0.1678 | 79 (84.0) | 0.0103 |

| Body weight (kg) | 62.6 ± 11.0 | 62.0 ± 11.1 | 63.3 ± 10.6 | 0.0522 | 64.4 ± 12.2 | 0.0722 |

| Height (cm) | 161.4 ± 8.5 | 160.9 ± 8.5 | 162.3 ± 8.4 | 0.0047 | 162.4 ± 7.9 | 0.0689 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.9 ± 3.2 | 23.9 ± 3.2 | 24.0 ± 3.1 | 0.6021 | 24.3 ± 3.4 | 0.2780 |

| Underlying disease | ||||||

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 626 (43.1) | 395 (42.2) | 192 (45.2) | 0.3160 | 39 (41.5) | 0.9132 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 711 (48.9) | 458 (49.0) | 199 (46.8) | 0.4825 | 54 (57.4) | 0.1301 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 155 (10.7) | 108 (11.6) | 41 (9.6) | 0.3489 | 6 (6.4) | 0.1662 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Hypertension (%) | 1053 (72.4) | 674 (72.1) | 306 (72.0) | 1.0000 | 73 (77.7) | 0.2763 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 830 (57.1) | 522 (55.8) | 253 (59.5) | 0.2148 | 55 (58.5) | 0.6635 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 416 (28.6) | 249 (26.6) | 137 (32.2) | 0.0378 | 30 (31.9) | 0.2749 |

| Metabolic syndrome (%) | 779 (53.6) | 489 (52.3) | 235 (55.3) | 0.3192 | 55 (58.5) | 0.2789 |

| H. pylori antibody positive (%) | 700 (48.1) | 509 (54.4) | 132 (31.1) | <0.0001 | 59 (62.8) | 0.1546 |

| Others concurrent disease (%) | 650 (44.7) | 429 (45.9) | 180 (42.4) | 0.2395 | 41 (43.6) | 0.7448 |

| Previous history of peptic ulcer (%) | 311 (21.4) | 202 (21.6) | 83 (19.5) | 0.4292 | 26 (27.7) | 0.1925 |

| Habit | ||||||

| Current tobacco smoking (%) | 151 (10.4) | 100 (10.7) | 32 (7.5) | 0.0752 | 19 (20.2) | 0.0102 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 591 (40.6) | 364 (38.9) | 181 (42.6) | 0.2103 | 46 (48.9) | 0.0611 |

| Coffee consumption (%) | 767 (52.8) | 482 (51.6) | 233 (54.8) | 0.2663 | 52 (55.3) | 0.5169 |

| Aspirin use | ||||||

| Enteric-coated aspirin (%) | 1300 (89.4) | 861 (92.1) | 361 (84.9) | 0.0001 | 78 (83.0) | 0.0063 |

| Duration of aspirin use (year) | 4.6 ± 4.4 | 4.5 ± 4.4 | 4.7 ± 4.4 | 0.4679 | 5.0 ± 4.7 | 0.2924 |

| Concomitant drug | ||||||

| Other antiplatelet (%) | 355 (24.4) | 228 (24.4) | 107 (25.2) | 0.7860 | 20 (21.3) | 0.6128 |

| Anticoagulant (%) | 175 (12.0) | 125 (13.4) | 43 (10.1) | 0.1092 | 7 (7.4) | 0.1077 |

| Other NSAID (%) | 94 (6.5) | 60 (6.4) | 31 (7.3) | 0.5593 | 3 (3.2) | 0.2642 |

| Antihypertensive drug (%) | 1084 (74.6) | 701 (75.0) | 312 (73.4) | 0.5464 | 71 (75.5) | 1.0000 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 754 (51.9) | 478 (51.1) | 219 (51.5) | 0.4390 | 57 (60.6) | 1.0000 |

| Lipid-lowering drug (%) | 753 (51.8) | 478 (51.1) | 219 (51.5) | 0.9069 | 56 (59.6) | 0.1299 |

| HMG-Co A reductase inhibitor | 682 (46.9) | 430 (46.0) | 201 (47.3) | 0.6815 | 51 (54.3) | 0.1303 |

| Antidiabetic drug (%) | 275 (18.9) | 160 (17.1) | 94 (22.1) | 0.0297 | 21 (22.3) | 0.2027 |

A total of 1454 participants were categorized into three groups by endoscopy: the group with absence of mucosal break (AMB), the group with gastroduodenal erosion (erosion), and the group with gastroduodenal ulcer (ulcer). The proportion of participants in each demographic category was examined among the three groups. Categorical variables were tested with Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables with Welch’s two sample t-test

AMB absence of mucosal break

a p value between AMB and erosion

b p value between AMB and ulcer

Baseline prevalence of gastroduodenal injury

The point prevalence of gastroduodenal ulcer was 6.5 % and erosion, 29.2 % (Table 1).

Among 94 patients with ulcer, the majority had gastric ulcer (80 cases, 85.1 %), following duodenal ulcer (10 cases, 10.6 %) and gastroduodenal ulcers (4 cases, 4.3 %).

Mean age was unexpectedly lower in the erosion (67.3 ± 9.3 years) and ulcer groups (65.1 ± 10.2 years) than in the group absent of mucosal break (AMB) (68.8 ± 9.5 years) (p = 0.0060 and p = 0.0009, respectively). In comparison with the AMB group, the ulcer group had greater proportions of male patients and current smokers (p = 0.0103 and p = 0.0102, respectively). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was higher (p = 0.0378), and that of H. pylori antibody positive was lower only in the erosion group (p < 0.0001). Use of enteric-coated aspirin was significantly lower in the erosion group (84.9 %) and in the ulcer group (83.0 %) than in the AMB group (92.1 %) (p = 0.0001 and p = 0.0063, respectively).

Risk of gastroduodenal injury

According to risk analysis (Tables 2, 3), current smoking and H. pylori antibody positive were significant risk factors for ulcer: OR = 1.87 (1.03–3.25, p = 0.0321) and OR = 1.83 (95 % CI 1.18–2.88, p = 0.0082), respectively. However, a reduced risk of erosion was found with H. pylori antibody positive: OR = 0.34 (0.26–0.44, p < 0.0001), and a reduced risk of ulcer was found in the elderly population (>65 years old): OR = 0.60 (0.39–0.94, p = 0.0246). The risk for erosion but not for ulcer was significantly lower in use of enteric-coated aspirin (OR = 0.47, 0.32–0.70, p = 0.0002) than in use of buffered aspirin (OR = 0.57, 0.32–1.05, p = 0.0569).

Table 2.

Factors associated with risk of gastroduodenal ulcer

| Factor | Unadjusted OR | p value | Adjusted OR | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥65 years | 0.58 (0.38–0.88) | 0.0109 | 0.60 (0.39–0.94) | 0.0246 |

| Men | 1.94 (1.14–3.55) | 0.0212 | 1.45 (0.81–2.74) | 0.2261 |

| Current tobacco smoking | 2.20 (1.24–3.71) | 0.0047 | 1.87 (1.03–3.25) | 0.0321 |

| Alcohol use | 1.44 (0.94–2.20) | 0.0891 | 1.18 (0.75–1.86) | 0.4736 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.25 (0.79–1.94) | 0.3331 | 1.12 (0.52–2.22) | 0.7526 |

| H. pylori antibody positive | 1.87 (1.21–2.91) | 0.0050 | 1.83 (1.18–2.88) | 0.0082 |

| History of peptic ulcer | 1.48 (0.91–2.34) | 0.1063 | 1.52 (0.91–2.47) | 0.0988 |

| Enteric-coated aspirin | 0.53 (0.31–0.97) | 0.0285 | 0.57 (0.32–1.05) | 0.0569 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 0.37 (0.17–0.74) | 0.0091 | 0.34 (0.15–0.68) | 0.0050 |

| H2-receptor antagonist | 0.80 (0.45–1.35) | 0.4251 | 0.62 (0.34–1.06) | 0.0967 |

| Cytoprotective drug | 0.93 (0.51–1.61) | 0.8158 | 0.84 (0.45–1.48) | 0.5703 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 0.95 (0.62–1.46) | 0.8211 | 0.87 (0.55–1.34) | 0.5214 |

| HMG-Co A reductase inhibitor | 1.36 (0.90–2.09) | 0.1489 | 1.38 (0.90–2.14) | 0.1450 |

| Antidiabetic drug | 1.25 (0.74–2.04) | 0.3801 | 1.20 (0.55–2.78) | 0.6527 |

Factors associated with gastroduodenal injuries suggestive in Table 1, with significant difference and established for gastroduodenal injuries according to previous studies, were examined for risk of gastroduodenal ulcer using data of 1423 participants excluding those without H. pylori information. Risk of gastroduodenal ulcer was estimated by the odds ratio with 95 % confidential interval using a monovariate (“Unadjusted”) or multivariate (“Adjusted”, which adjusted by all listed variables) logistic regression model

Table 3.

Factors associated with risk of gastroduodenal erosion

| Factor | Unadjusted OR | p value | Adjusted OR | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥65 years | 0.82 (0.64–1.05) | 0.1210 | 0.83 (0.64–1.09) | 0.1768 |

| Men | 1.23 (0.94–1.61) | 0.1290 | 1.25 (0.93–1.70) | 0.1413 |

| Current tobacco smoking | 0.69 (0.45–1.04) | 0.0857 | 0.65 (0.41–1.01) | 0.0597 |

| Alcohol use | 1.19 (0.94–1.50) | 0.1497 | 1.14 (0.87–1.48) | 0.3447 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.30 (1.00–1.67) | 0.0465 | 1.06 (0.69–1.60) | 0.7917 |

| H. pylori antibody positive | 0.38 (0.29–0.48) | <0.0001 | 0.34 (0.26–0.44) | <0.0001 |

| History of peptic ulcer | 0.94 (0.70–1.25) | 0.6599 | 1.05 (0.77–1.43) | 0.7597 |

| Enteric-coated aspirin | 0.47 (0.33–0.67) | <0.0001 | 0.47 (0.32–0.70) | 0.0002 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 0.44 (0.32–0.61) | <0.0001 | 0.32 (0.22–0.46) | <0.0001 |

| H2-receptor antagonist | 0.60 (0.44–0.81) | 0.0010 | 0.49 (0.36–0.68) | <0.0001 |

| Cytoprotective antiulcer drug | 1.12 (0.82–1.51) | 0.4776 | 1.01 (0.72–1.39) | 0.9592 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 1.12 (0.88–1.42) | 0.3496 | 1.21 (0.94–1.56) | 0.1339 |

| HMG-Co A reductase inhibitor | 1.03 (0.81–1.30) | 0.8159 | 1.05 (0.82–1.35) | 0.6838 |

| Antidiabetic drug | 1.34 (1.00–1.78) | 0.0484 | 1.27 (0.79–2.05) | 0.3289 |

Factors associated with gastroduodenal injuries suggestive in Table 1, with significant difference and established for gastroduodenal injuries according to previous studies, were examined for risk of gastroduodenal erosion using data of 1330 participants excluding those without H. pylori information and with ulcer. Risk of gastroduodenal erosion was estimated by the odds ratio with 95 % confidential interval using a monovariate (“Unadjusted”) or multivariate (“Adjusted”, which adjusted by all listed variables) logistic regression model

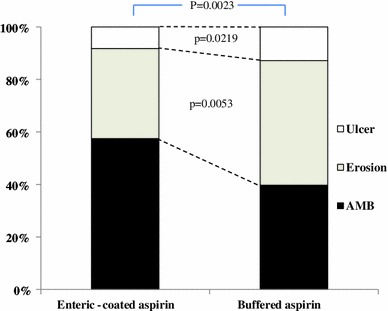

In the analysis of 690 patients not treated with antiulcer drugs, the prevalence of ulcer and erosion were significantly lower with use of enteric-coated aspirin (7.8 and 33.5 %, respectively) than with use of buffered aspirin (12.8 and 47.4 %, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Use of aspirin formulations and prevalence of gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion in patients not treated with antiulcer drugs. In 690 participants who were not treated with antiulcer drugs, prevalence of gastroduodenal erosion and ulcer were compared between patients receiving enteric-coated (88.7 %) and buffered aspirin (11.3 %). AMB absence of mucosal break

Antiulcer drug therapy

Anti-ulcer drugs were prescribed for gastroprotection in 52.5 %. PPI, H2RA, and cytoprotective antiulcer drugs or their combination were used with similar rates, whereas use of PGA or its combination was much lower. Use of PPI alone was lower in the erosion group (10.1 %) and in the ulcer group (7.4 %) than in the AMB group (20.6 %) (p < 0.0001, p = 0.0014, respectively). However, the difference in use of H2RA was detected only in the erosion group. Moreover, use of cytoprotective antiulcer drugs was higher in the erosion group (p = 0.0364). In analyses, risks of both ulcer and erosion were significantly reduced with PPI therapy (OR = 0.34, 0.15–0.68, p = 0.0050 and OR = 0.32, 0.22–0.46, p < 0.0001, respectively). However, in the H2RA therapy group the risk of erosion but not of ulcer was reduced (OR = 0.49, 0.36–0.68, p < 0.0001). No relation was found between therapy with cytoprotective drugs and those risks (Tables 2, 3, 4).

Table 4.

Relationship between aspirin-associated gastroduodenal injuries and antiulcer drug treatment

| Total n = 1454 |

AMB n = 935 (64.3) |

Erosion n = 425 (29.2) |

p valuea | Ulcer n = 94 (6.5) |

p valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No antiulcer drug (%) | 690 (47.5) | 390 (41.7) | 242 (56.9) | <0.0001 | 58 (61.7) | 0.0003 |

| PPI alone (%) | 243 (16.7) | 193 (20.6) | 43 (10.1) | <0.0001 | 7 (7.4) | 0.0014 |

| H2RA alone (%) | 263 (18.1) | 192 (20.5) | 58 (13.6) | 0.0025 | 13 (13.8) | 0.1367 |

| CAD alone (%) | 171 (11.8) | 98 (10.5) | 62 (14.6) | 0.0364 | 11 (11.7) | 0.7246 |

| PGA alone (%) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.5275 | 0 (0.0) | 1.0000 |

| PPI + H2RA (%) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.5275 | 0 (0.0) | 1.0000 |

| PPI + CAD (%) | 33 (2.3) | 26 (2.8) | 7 (1.6) | 0.2558 | 0 (0.0) | 0.1606 |

| PPI + PGA (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.0000 | 1 (1.1) | 0.0914 |

| CAD + PGA (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.3125 | 0 (0.0) | 1.0000 |

| H2RA + CAD (%) | 47 (3.2) | 34 (3.6) | 9 (2.1) | 0.1803 | 4 (4.3) | 0.7716 |

| PPI + H2RA + CAD (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.3125 | 0 (0.0) | 1.0000 |

Association of gastroduodenal injuries with concomitant use of antiulcer drug was analyzed using data of 1454 participants. The proportions of participants who received each category of antiulcer treatment were examined in the three groups of gastroduodenal conditions. Those in each treatment category were evaluated between the erosion group or the ulcer group versus the AMB group with Fisher’s exact test

PPI proton pump inhibitor, H2RA histamine 2-receptor antagonist, CAD cytoprotective antiulcer drug, PGA prostaglandin analog

a p value between AMB and Erosion

b p value between AMB and Ulcer

Upper GI cancer

Among 1,492 participants who received endoscopy, 37 participants (2.5 %, 95 % CI 1.75–3.40) had upper GI cancer, 4 patients (0.27 %, 0.07–0.68) had esophageal cancer, and 33 patients (2.21 %, 95 % CI 1.53–3.09) had gastric cancer. Additionally, colon cancer was found in one patient.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that endoscopic gastroduodenal injuries were prevalent (35.7 %) among low-dose aspirin users in Japan, similar to Western countries. However, significant differences were found between the two regions in the methods aspirin was prescribed and the risk factors and drug treatment for gastroduodenal injuries. Use of other NSAIDs (6.5 %) with aspirin was rare in the present study, while it is frequent in Western countries. In spite of the recommendations in the AHA consensus and Japanese guidelines [12, 13], the use of PPI treatment was relatively low (19 %) and was similar to the use of H2RA or cytoprotective antiulcer agents. Cytoprotective agents are not generally used in Western countries. The recent approval (2010) of PPI for the prevention of mucosal injury in Japan may be contributing to the low PPI use.

Prevalence of gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion

The prevalence of endoscopic gastroduodenal ulcer associated with low-dose aspirin (6.5 %) was lower in our study than in previous studies. The prevalence of ulcer and erosion were 18 and 42 %, respectively, among 101 Japanese patients with ischemic heart disease in the study of Nema et al. [14], while that of upper GI ulcer was 12.4 % in 305 Japanese patients in the study of Shiotani et al. [15]. According to Yeomans et al., the point prevalence was 11 % for endoscopic gastroduodenal ulcer and 63 % for erosion in 187 patients taking aspirin for at least 24 days [4]. Factors contributing to the lower prevalence of ulcer or erosion in our study may be as follows: (1) a total of 41 % of the participants were treated with PPI or H2RA; (2) concomitant use of other NSAIDs was much lower; and (3) the criterion for mucosal ulcer was a mucosal break of 5 mm or greater in diameter with unequivocal depth. Nonetheless, by our estimation the prevalence of low-dose aspirin-induced endoscopic gastroduodenal ulcer in Japan is approximately 5–10 % in clinical practice.

Risk factors for gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion

Clinically important risk factors for aspirin-associated upper GI bleeding include aging, history of peptic ulcer or GI bleeding, concomitant use of anticoagulants or NSAIDs, and H. pylori infection in Western populations [16]. However, a limited number of studies endoscopically examined ulcer risk factors [15, 17]. In a study of Shiotani et al. [17] aging, history of peptic ulcer, and concomitant use of antithrombotic drugs and NSAIDs were associated with peptic ulcer, but regular alcohol drinking, smoking, and H. pylori infection were not in 425 low-dose aspirin users. In our study, a history of peptic ulcer, and the concomitant use of anticoagulants and NSAIDs had little association with endoscopic gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion. The reason may include (1) elderly patients with high risk for peptic ulcer such as those taking concomitant anticoagulants and NSAIDs might not be recruited, and (2) the number of concomitant NSAID use in this study was small, which may lead to an underestimation of the risk.

Aging was a risk factor for low-dose aspirin related gastroduodenal ulcer in many studies [4, 16, 17], whereas we observed that age >65 years old was associated a significant reduction in the risk of aspirin-associated ulcer. Furthermore in the analysis of 690 patients not treated with antiulcer drugs, the prevalence of ulcer was significantly lower in the elderly population (See the Supplementary table). The consensus of prior data is that risk of aspirin-associated ulcer increases with advancing age. This means that there may be a significant bias in our methodology or the Japanese may differ in gastric physiology from the rest of the world. In Japanese populations, the older generation has significantly reduced gastric acid secretion compared to younger generations due to atrophic gastritis [18]. Therefore, younger generations may have an inherently higher acid secretion and thus a higher risk of ulcers. However, the age-associated increase in atrophic gastritis is not specific gastritis is not a phenomenon which is specific to Japanese patients. Therefore, it is very likely to be a significant bias in our methodology that elderly patients with at high risk for peptic ulcer might not be recruited.

According to studies of Western populations, the presence of H. pylori infection is a significant risk for gastroduodenal ulcer [19]. Our study also demonstrated a twofold increase in ulcer risk in the presence versus the absence of H. pylori antibody. However, those results were conflicting with those of Shiotani et al. [15, 17] in Japanese populations where H. pylori infection was not associated with peptic ulcer in low-dose aspirin users. The findings may be affected by the study population and the definition of ulcer, which will be discussed in a separate section. In our study, the risk of erosion was significantly lower in the presence of H. pylori antibody. The cause and pathogenesis of aspirin-induced endoscopic gastroduodenal ulcer may be different from those of erosion in the presence of H. pylori infection.

Aspirin formulation

The prevalence of gastroduodenal injuries was significantly lower with enteric-coated aspirin than with buffered aspirin in our study. Others found that the risks of upper GI bleeding were similar among three forms of aspirin [20]. Although the prevalence of endoscopic gastroduodenal erosion was significantly lower with enteric-coated aspirin than with buffered aspirin, ulcer frequency was similar between the two formulations in the study of Nema et al. [21]. Dammann et al. [22] demonstrated that endoscopic gastroduodenal mucosal lesions were significantly less likely with enteric-coated aspirin (100 mg/day) than with plain aspirin, and the lesion score with coated aspirin was similar to that of placebo without aspirin. Further studies on the influence of aspirin formulation are needed in Japan.

Antiulcer drugs for prevention of gastroduodenal injury

Use of PPI was significantly less in the patients with ulcer or erosion, whereas use of H2RA was less in the patients with erosion, but not with ulcer. Use of cytoprotective drugs, which are widely prescribed in Japan, was higher in the patients with erosion. According to the risk analyses, only PPI presents reduced risks of both ulcer and erosion. The usefulness of PPI in the prevention of ulcers induced by low-dose aspirin is well established in Western countries and in Japan. In a comparative study by Yeomans et al. [23] the development of gastrointestinal ulcer was lower (1.6 %) with esomeprazole 20 mg/day than with placebo (5.4 %), demonstrating a reduction of 70 % in the 991 participants aged ≥60 years receiving low-dose aspirin for 26 weeks without preexisting endoscopic ulcers and without concomitant NSAIDs. Although their study design differed from ours, their findings support our study results. The effectiveness of PPI for the prevention of low-dose aspirin associated gastric or duodenal ulcers was demonstrated in a randomized comparative study by Sugano et al. [24] of a PPI, lansoprazole (15 mg/day), versus a cytoprotective antiulcer drug, gefarnate (100 mg/day), for secondary prevention. The recurrence of ulcers was 90 % lower with lansoprazole than with gefarnate for an administration of 12 months or longer. According to Taha et al. [25] H2RA treatment with famotidine for 20 weeks reduced the risk of aspirin-induced peptic ulcer by 80 %. However, the risk of gastroduodenal erosion but not of ulcer was significantly lower with H2RA in our study. Study design and the ethnicity of the study populations may have contributed to the difference in results between the two studies.

Definition of ulcer and erosion as surrogate marker

Endoscopic gastroduodenal ulcer has been suggested to be a useful surrogate marker for potentially serious aspirin adverse event such as GI bleeding [26]. However, as described by Graham [27], ulcers are often defined by a mucosal defect of “3 mm or more” or “5 mm or more” in diameter in clinical studies, but aspirin-induced ulcer is often difficult to distinguish from erosion. No internationally recognized clear definition of “ulcer” or “a method of measuring ulcer size” has been established. Our definition of endoscopic ulcer was a mucosal defect 5 mm or more in diameter. However, when an ulcer with a 10 mm or larger diameter is defined as a “large ulcer,” 25 % or more of ulcers were large ulcers in patients receiving H2RA or a cytoprotective antiulcer drug, but none of the ulcers were large ulcers in those receiving PPI in the present study (data not shown). Thus, the size of ulcers must be carefully defined for assessing effectiveness of antiulcer drugs in clinical studies that use endoscopically defined ulcers as the primary endpoint. A large cohort study is needed to clarify the risk factors of serious adverse events such as GI bleeding, and to verify endoscopically defined ulcer as a useful surrogate marker of GI bleeding in low-dose aspirin users.

Gastric cancer

This is the first study reporting the prevalence of gastric cancer diagnosed by endoscopy among aspirin users. Among 1,492 patients who received endoscopy, 37 patients had gastric cancer (2.5 %). Reports on the possible prevention of gastric cancer with aspirin have been published [28, 29], but it seems that more studies are necessary in the regions with a high prevalence of gastric cancer, such as Japan.

Limitation

We did not conduct the systematic screening in each hospital for patient recruitment. Our registry recruited patients taking preventive aspirin for high risk CV in clinical practice and gave informed consent to this study. Inclusion bias may be a potential limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Gastroduodenal ulcer and erosion are common among patients receiving low-dose aspirin for prophylaxis of CV disease in the Japanese population (35.7 %). Factors that increase risks of mucosal injuries are current tobacco smoking and the presence of H. pylori infection. The use of PPI is helpful to reduce the risk of ulcer and erosion. Furthermore, the association between endoscopic ulcer and serious complications such as GI bleeding should be clarified in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Professor David Y. Graham (of Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center at Houston, Texas, United States) for his helpful suggestions and to Koji Shimamoto, Hiroko Usami, and Yasuko Ueda for their assistance with laboratory work and statistical analyses. This study was sponsored by the Japan Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

SG received research grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Eisai, Boehringer Ingelheim, Otsuka, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and received honorarium for sitting on advisory panels from Eisai, Sanofi-Aventis, Otsuka, Bayer, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Astellas, Pfizer, Medtronics-Japan, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Takeda, Daiichi-Sankyo, Mochida, and MSD. KS received grants from AstraZeneca, Takeda, Astellas and Daiichi-Sankyo and also sat on advisory panels for AstraZeneca, and Takeda. YI received honorarium for lecturing from Sanofi-Aventis, Daiichi-Sankyo and Bayer, and sat on advisory panels for AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Sanofi-Aventis. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Organizing Committee

Yasuo Ikeda (Chair), Shinichiro Uchiyama, Yasushi Okada, Kazuyuki Shimada, Shinya Goto, Kentaro Sugano, Hideyuki Hiraishi, Naomi Uemura, Hideki Origasa.

Endoscopic Evaluation Committee

Naomi Uemura (Chair), Takashi Kawai, Shinichi Nakamura, Chouitsu Sakamoto, Hidekazu Suzuki.

Event Ascertainment Committee

Shinichiro Uchiyama (Chair), Yasushi Okada, Kazuyuki Shimada, Shinya Goto.

Data Monitoring Committee

Saichi Hosoda (Chair), Yukito Shinohara, Toshifumi Hibi.

Data Coordinating Center

Hiroko Usami.

List of participating investigators

(National Center for Global Health and Medicine) Gastroenterology Junichi Akiyama, Naomi Uemura Cardiology Michiaki Hiroe, Osamu Okazaki (Hiroshima University) Clinical Neuroscience and Therapeutics Rie Hanaoka, Hiroki Imagawa, Shinobu Imagawa, Shosuke Kitamura, Takayasu Kuwahara, Taiji Matsuo, Sayaka Oba, Toshiho Ohtsuki, Toshiko Onitake, Youji Sanomura, Takayoshi Shisido, Akemi Takamura, Masana Tatsugami, Yoshihiro Wada, Shigeto Yoshida (Tokai University School of Medicine) Gastroenterology Jun Koike, Masashi Matsushima, Tetsuya Mine, Takayuki Shirai, Takayoshi Suzuki, Kenichi Watanabe Cardiology Shinya Goto, Teruhisa Tanabe, Koichiro Yoshioka Neurology Shigeharu Takagi Neurosurgery Mitsunori Matsumae (Tokyo Medical University Ibaraki Medical Center) Gastroenterology Tsuyoshi Hirayama, Tadashi Ikegami, Masanori Ito, Shinichi Ito, Junichi Iwamoto Cardiology Masamitsu Asano, Akihiro Fukuda, Shinji Okubo Neurology Suguru Nojima, Kaoru Yamazaki (Dokkyo Medical University Hospital) Gastroenterology Takafumi Hoshino, Jun Ishikawa, Kazunari Kanke, Mitsunori Maeda, Masakazu Nakano, Rieko Ogura, Yutaka Okamoto, Yasuyuki Saifuku, Takako Sasai, Makoto Suzuki, Akihiro Tajima, Keiichi Tominaga, Mariko Uchizono, Hidetaka Watanabe, Michiko Yamagata, Yoshimitsu Yamamoto, Kenji Yoshida Hypertension and Cardiorenal Medicine Shigeo Horinaka, Kimihiko Ishimura, Koichi Kono, Akihisa Yabe, Hiroshi Yagi Neurosurgery Yasuhisa Daimon, Atsuko Ebata, Hidehiro Takekawa (Uji Hospital) Gastroenterology Tadashi Higaki, Kennji Mayumi, Shohei Sawada, Kaoru Shirai, Nami Takeda (Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine) Gastroenterology Katsunori Iijima Cardiology Ryoji Koshida, Hiroaki Shimoaki, Morihiko Takeda (Keio University School of Medicine) Gastroenterology Rie Hanaoka, Hiroki Imagawa, Shinobu Imagawa, Shosuke Kitamura, Takayasu Kuwahara, Taiji Matsuo, Sayaka Oba, Toshiho Ohtsuki, Toshiko Onitake, Youji Sanomura, Takayoshi Shisido, Akemi Takamura, Masana Tatsugami, Yoshihiro Wada, Shigeto Yoshida (Hamamatsu University School of Medicine) Clinical Research Development Center Takahisa Furuta, Mutsuhiro Ikuma, Masafumi Nishino, Satoshi Osawa, Kenichi Yoshida Neurosurgery Hisaya Hiramatsu, Hiroki Namba Clinical pharmacology Kazuhiko Takeuti, Akiko Utsumi, Hiroshi Watanabe (Teine Keijinkai Hospital) Cardiology Mitsuharu Fukasawa, Akio Katanuma, Toshifumi Kin, Fukuo Komaba, Akira Kurita, Takeshi Matsui, Shinya Mitsui, Harutatsu Muto, Hiroyuki Nishimori, Masafumi Nomura, Maki Ohtsubo, Manabu Osanai, Hayato Shida, Kuniyuki, Takahashi, Tanaka Tanaka, Kei Yane (University of Toyama) 1st Dept. Internal Medicine Tomoki Kameyama, Naoya Kuwayama 2nd Dept. Internal Medicine Nozomi Fujii, Takashi Nozawa 3rd Dept. Internal Medicine Ayumu Hosokawa, Tohishiko Kudo, Takako Miyazaki, Tadahiro Orihara, Toshiro Sugiyama Neurology Akira Matsuki, Yoshiharu Taguchi, Shutaro Takashima, Kortaro Tanaka Neurosurgery Shunro Endo, Hideo Hamada, Nakamasa Hayashi, Tadakazu Hirai (Oji General Hospital) Gastroenterology Tadashi Doi, Akihito Fujimi, Yuji Kanisawa, Hideaki Ohta, Toshinori Okuda, Yasuhiro Sato Cardiology Tadashi Doi, Akihito Fujimi, Katsuhisa Ishii, Yuji Kanisawa, Nobuo Kato, Tomoaki Matsumoto, Hideaki Ohta, Hitoshi Ooiwa, Yasuhiro Sato, Daisuke Yoshida Neurosurgery Yoshifumi Horita, Shigeki Kashiwabawa, Takeshi Mikami (Fujita Health University) Gastroenterology Ichiro Hirata, Tomoyuki Shibata Cardiology Masatsugu Iwase, Yukio Ozaki, Masayoshi Sarai, Eiichi Watanabe Neurology Kunihiko Asakura, Hideo Hara, Takateru Mihara, Tatsuro Mutoh, Takako Takeuchi, Akihiro Ueda (Gunma University Hospital) Cardiology Masashi Arai, Yoshiaki Kaneko, Akihiko Nakano Neurology Koichi Okamoto Endoscopy and Endoscopic Surgery Hiroko Hosaka, Osamu Kawamura, Motoyasu Kusano, Yasuyuki Shimoyama (Kokura Memorial Hospital) Cardiology Yoshio Kazuno, Tomoharu Yoshida (Odate Municipal General Hospital) Gastroenterology Hitoshi Ogasawara Neurosurgery Masahiro Sasaki (Nakamura Memorial Hospital) Neurosurgery Jyoji Nakagawara, Yoshinobu Seo, Toshiiti Watanabe (Iwate Medical University) Neurology and geriatric Toshimi Chiba, Kuniko Watanabe, Hisashi Yonezawa (Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine) Gastroenterology Hitoshi Maruyama Cardiology Hiroshi Akazawa, Hiroshi Hasegawa, Naoki Ishio, Nakabumi Kuroda, Yoichi Kuwabara, Hideyuki Miyauchi, Taichi Murayama, Toshio Nagai, Keiichi Nakagawa, Tohru Oka, Satoshi Shindo, Ichiro Shiojima, Hiroyuki Takano, Toko Toko (Institute of Brain and Blood Vessels Mihara Memorial Hospital) Ban Mihara, Masaki Takao, Yutaka Tomita Gastroenterology Takayuki Takahashi (Tokyo Women’s Medical University) Gastroenterology Kenji Maruyama, Yoko Masuda, Shinichi Nakamura, Yoshio Uetsuka Cardiology Kagari Murasaki, Sono Tooi Neurology Tomomi Kimura (Nanpu Hospital) Gastroenterology Takako Imamura, Hiromitsu Karasumaru, Akio Matsuda, Tooru Niihara, Tatsuyuki Nioh, Syunji Shimaoka, Kotarou Tashiro Cardiology Kazuaki Kiyonaga, Shinichirou Toyoshima Neurosurgery Kazuhiro Kusumoto, Shunichi Yokoyama (Sapporo Medical University) 1st Internal Medicine Yoshiaki Arimura, Akira Goto, Akiyoshi Hashimoto, Masayo Hosokawa, Yoshinori Miyazaki, Hiroyuki Okuda, Kazuaki Shimamoto, Tokuma Tanuma, Nobuhiko Togashi, Kazufumi Tsuchihashi, Hiroyuki Yamamoto, Kentaro Yamashita Neurosurgery Masaki Saitoh (Kamiiida Daiichi General Hospital) Gastroenterology Kosuke Tachi Cardiology Satoshi Isobe (Nippon Medical University Hospital) Cardiology Hitoshi Takano (Jichi Medical University) Gastroenterology Hironari Ajibe, Tomosuke Hirasawa, Hiroyuki Osawa, Kiihi Satoh, Toru Yoshida Cardiology Kazuo Eguchi, Yukihiro Hojo, Satoshi Hoshide, Mitsunobu Murata, Masahisa Shimpo, Nozomu Takahashi, Shuichi Ueno, Keiji Yamamoto (Nayoro City General Hospital) Neurosurgery Hiroki Saito, Kazuhiro Sako.

(Hakodate Goryokaku Hospital) Gastroenterology Kaoru Kasahara, Toshihisa Kobayashi, Nobuaki Sugawara, Ryo Suzuki, Hiroyuki Takamaru, Hidenori Yamauchi, Atsushi Yawata Cardiology Hiroshi Oimatsu (Nihon University School of Medicine Itabashi Hospital) Gastroenterology and hepatology Shigeaki Mizuno, Junko Motoe Cardiology Masaaki Chiku, Satoshi Kunimoto, Kazumasa Miyake (Ichinomiya Municipal Hospital) Cardiology Chiyuki Chujyou, Youichi Iguchi, Shinichi Kanamori, Keiji Mizutani, Arihiro Nakano, Masako Oosawa, Tetsuo Shibata, Michiharu Yamada, Toshihiro Yamanaka (Kawasaki Medical School Hospital) Gastroenterology Akiko Shiotani Cardiology Yoji Neishi (NTT Medical Center Tokyo) Gastroenterology Nobuyuki Matsuhashi, Osamu Tagusari, Yumiko Yamaoka (Saitama Medical Center) Gastroenterology and hepatology Toru Aoyama, Katsuya Chinen, Shuko Isida, Kazuhito Kani, Junichi Kawashima, Naoya Miyagi, Shino Ono, Keiko Satou, Koji Yakabi, Masakatsu Yoshikawa Neurology Kyoichi Nomura Gastroenterology Madoka Hashimoto, Masayoshi Uehara (Seiseikai Kumamoto Hospital) Cardiology Junjiroh Koyama Neurology Toshiro Yonehara (Mie University Hospital) Cardiology Hiroshi Nakashima, Muneyoshi Tanimura, Akihiro Tsuji Neurology Akira Taniguchi Endoscopy and Endoscopic Surgery Ichiro Imoto, Kyosuke Tanaka Clinical Research Development Center Masakatsu Nishikawa (Sapporo City General Hospital) Gastroenterology Michio Nakamura, Shuji Nishikawa Cardiology Hiroyuki Fukuda Neurosurgery Masayoshi Takigami (Yokohama City University Medical Center) Cardiovascular Center Kiyoshi Hibi, Kazuo Kimura, Atsushi Kokawa, Kengo Tsukahara (National Hospital Organization Kagoshima Medical Center) Cerebrovascular disease Rikuzo Hamada, Naoko Tsubouchi (Hokkaido University Hospital) Gastroenterology Mototsugu Kato, Shouko Ono Cardiology Tomoo Furumoto, Daisuke Gotou, Naoki Ishimori, Nozomu Kawashima, Mamoru Sakakibara, Takamitsu Souma (Yokohama Sakae Kyosai Hospital) Neurosurgery Motohiro Nomura, Hiro Satoh, Hiroshi Shima (Komaki City Hospital) Cardiology Hajime Imai, Taizo Kondo, Akihiro Miyata, Itaru Ohyama (National Hospital Organization Yokohama Medical Center) Cardiology Kazunori Iwade, Shouzo Matsushima (Shimane University Faculty of Medicine) Gastroenterology Yuji Amano, Kenji Furuta, Norihisa Ishimura, Kenji Koshino, Masaharu Miki Neurology Hirokazu Bokura, Hiroaki Oguro, Shuhei Yamaguchi Cardiology Yutaka Ishibashi (Oita University Faculty of Medicine) Gastroenterology Tadayoshi Okimoto, Jin Tanahashi Cardiology Munenori Kotoku, Shigeru Naono, Takashi Sato, Akira Tamura (National Hospital Organization Kyushu Medical Center) Gastroenterology Naohiko Harada Hematology Toshiyasu Ogata, Yasushi Okada, Shinji Satoh (Teikyo University Hospital) Gastroenterology Takatsugu Yamamoto Cardiology Shuichi Ishikawa, Satoshi Koganezawa, Ken Kozuma, Yoshitaka Shiratori, Hidenori Watanabe (Kushiro City General Hospital) Neurosurgery Toshio Imaizumi, Kazuhiko Yonezawa (Shinshu University Hospital) Gastroenterology Yuichi Sato 1st Internal Medicine Yoshifusa Aizawa, Satoru Hirono Neurology Yasuhisa Akaiwa (Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital) Neurosurgery Kazuhiko Nishino (University of Yamanashi Faculty of Medicine) Neurosurgery Kazuya Kanemaru, Hiroyuki Kinouchi, Masao Sugita (University of Yamanashi Hospital) Gastroenterology Tadashi Sato (NTT Medical Center Sapporo) Gastroenterology Shigeru Furukawa, Akihito Kobayashi, Tatsumi Koshiyama, Kimitoshi Kubo, Ken Nishi, Amane Oota, Youko Tsukuda, Akiko Yokoyama Cardiology Shigeru Furukawa, Tetsuro Kohya, Noriyuki Miyamoto (Konan Kosei Hospital) Gastroenterology Yoji Sasaki Cardiology Shinichi Ishikawa (Ehime University Hospital) Gastroenterology Yoshiou Ikeda, Hidehiro Murakami, Akiyoshi Ogimoto Neurosurgery Hideaki Watanabe (Jichi Medical Unversity Saitama Medical Center) Gastroenterology Satohiro Matsumoto, Noriyoshi Sagihara Cardiology Kenshiro Arao, Shin-Ichi Momomura, Kenichi Sakakura (Tosei General Hospital) Gastroenterology Takao Hayasi, Tetsuo Matsuura, Keiichi Morita, Toyohiro Sakata, Yuko Simizu Cardiology Takahiro Kannbara, Yusuke Uemura (Saga University) Gastroenterology Yasuhisa Sakata, Ryo Shimoda, Seiji Tsunada Cardiology Shigemasa Hashimoto, Tadashi Yamamoto (Tsuchiya General Hospital) Gastroenterology Yasuhiko Hayashi, Shohei Ishimaru, Masaru Shimamoto, Seiji Touge Cardiology Tomoharu Kawase, Takehito Tokuyama (Okayama Medical Center) Gastroenterology Hiromi Matsubara, Yoshihiro Oofuji Cardiology Tomohiko Mannami (National Defense Medical College Hospital) Gastroenterology Ryota Hokari Cardiology Fumitaka Ohsuzu (Toda Chuo General Hospital) Gastroenterology Masataka Nishi Cardiology Tadashi Nagao, Takashi Uchiyama.

(Yamaguchi University Hospital) Endoscopy and Endoscopic Surgery Shingo Higaki, Jun Nishikawa Cardiology Toshirou Miura (Shinshu University Hospital) Cardiology Hiroki Kasai Endoscopy Taiji Akamatsu (Research Institute for Brain and Blood Vessels-Akita) Stroke care unit Tsuyoshi Mukoujima, Akifumi Suzuki.

(Suzulan Clinic) Masahide Wada.

Footnotes

The MAGIC Study Group: Management of Aspirin-induced Gastrointestinal Complications.

Trial registration: UMIN000000750.

References

- 1.Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high-risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisman SM, Graham DY. Evaluation of the benefits and risks of low-dose aspirin in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2197–2202. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eidelman RS, Hebert PR, Weisman SM, Hennekens CH. An update on aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2006–2010. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–1860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, et al. AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: 2002 Update: Consensus Panel Guide to Comprehensive Risk Reduction for Adult Patients Without Coronary or Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Diseases. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation. 2002;106:388–391. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000020190.45892.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayden M, Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:161–172. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García Rodríguez LA, Hernández-Díaz S, de Abajo FJ. Association between aspirin and upper gastrointestinal complications: systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:563–571. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakamoto C, Sugano K, Ota S, et al. Case–control study on the association of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Japan. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:765–772. doi: 10.1007/s00228-006-0171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeomans ND, Lanas AI, Talley NJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers during treatment with vascular protective doses of aspirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:795–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiba T, Seno H, Marusawa H, Wakatsuki Y, Okazaki K. Host factors are important in determining clinical outcomes of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1743-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Origasa H, Goto S, Shimada K, MAGIC Investigators et al. Prospective cohort study of gastrointestinal complications and vascular diseases in patients taking aspirin: rationale and design of the MAGIC Study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2011;25:551–560. doi: 10.1007/s10557-011-6328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1502–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guidelines for EBM Based Clinical Practice of Gastric Ulcer. 2nd ed. Team on EBM Based Clinical Practice of Gastric Ulcer, editors, Jiho; 2007. p. 101–10 (in Japanese).

- 14.Nema H, Kato M, Katsurada T, et al. Endoscopic survey of low-dose-aspirin-induced gastroduodenal mucosal injuries in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(Suppl 2):S234–S236. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiotani A, Sakakibara T, Yamanaka Y, et al. Upper gastrointestinal ulcer in Japanese patients taking low-dose aspirin. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:126–131. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanas A, Scheiman J. Low-dose aspirin and upper gastrointestinal damage: epidemiology, prevention and treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:163–173. doi: 10.1185/030079907X162656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiotani A, Nishi R, Yamanaka Y, et al. Renin-angiotensin system associated with risk of upper GI mucosal injury induced by low dose aspirin: renin angiotensin system genes’ polymorphism. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:465–471. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiotani A, Sakakibara T, Yamanaka Y, et al. The preventive factors for aspirin-induced peptic ulcer: aspirin ulcer and corpus atrophy. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:717–725. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanas A, Fuentes J, Benito R, Serrano P, Bajador E, Sáinz R. Helicobacter pylori increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking low-dose aspirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:779–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Jurgelon JM, Sheehan J, Koff RS, Shapiro S. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet. 1996;348:1413–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)01254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nema H, Kato M, Katsurada T, et al. Investigation of gastric and duodenal mucosal defects caused by low-dose aspirin in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:130–132. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181580e8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dammann HG, Burkhardt F, Wolf N. Enteric costing of aspirin significantly decreases gastroduodenal mucosal lesions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1109–1114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeomans N, Lanas A, Labenz J, et al. Efficacy of esomeprazole (20 mg once daily) for reducing the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with continuous use of low-dose aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2465–2473. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugano K, Matsumoto Y, Itabashi T, et al. Lansoprazole for secondary prevention of gastric or duodenal ulcers associated with long-term low-dose aspirin therapy: results of a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, double-dummy, active-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:724–735. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taha AS, McCloskey C, Prasad R, Bezlyak V. Famotidine for the prevention of peptic ulcers and esophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin (FAMOUS): a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:119–125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore A, Bjarnason I, Cryer B, et al. Evidence for endoscopic ulcers as meaningful surrogate endpoint for clinically significant upper gastrointestinal harm. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1156–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham DY. Endoscopic ulcers are neither meaningful nor validated as a surrogate for clinically significant upper gastrointestinal harm. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1147–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothwell PM, Fowkes FG, Belch JF, Ogawa H, Warlow CP, Meade TW. Effect of daily aspirin on long-term risk of death due to cancer: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang P, Zhou Y, Chen B, et al. Aspirin use and the risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1533–1539. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.