Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

To explore ovarian cancer survivors’ experiences of self-advocacy in symptom management.

Research Approach

Descriptive, qualitative.

Setting

A public café in an urban setting.

Participants

13 ovarian cancer survivors aged 26–69 years with a mean age of 51.31.

Methodologic Approach

Five focus groups were formed. Focus group discussions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The content was analyzed using the constant comparison method with axial coding. In-depth interviews with 5 of the 13 participants occurred via telephone one to five months after each focus group meeting to clarify and expand on identified themes. Preliminary findings were shared with all participants for validation.

Findings

Two major themes emerged from the data: (a) knowing who I am and keeping my psyche intact, and (b) knowing what I need and fighting for it. Exemplar quotations illustrate the diverse dimensions of self-advocacy. In addition, a working female-centric definition of self-advocacy was attained.

Conclusions

Women have varying experiences with cancer- and treatment-related symptoms, but share a common process for recognizing and meeting their needs. Self-advocacy was defined as a process of learning one’s needs and priorities as a cancer survivor and negotiating with healthcare teams, social supports, and other survivors to meet these needs.

Interpretation

This phenomenologic process identified key dimensions and a preliminary definition of self-advocacy that nurses can recognize and support when patients seek and receive care consistent with their own needs and preferences.

Knowledge Translation

Self-advocacy among female cancer survivors is a process of recognizing one’s needs and priorities and fighting for them within their cancer care and life. Practitioners can support female cancer survivors through the process of self-advocacy by providing them with skills and resources in making informed choices for themselves.

Cancer survivors, defined as anyone with a history of a cancer diagnosis, are increasingly required to play an active role in their health care because of growing emphasis on patient-centered care, complex healthcare structures, and long-term survivorship (Hewitt, Greenfield, & Stovall, 2006; Johnson, 2011). Understanding how patients engage in and manage their care throughout all stages of cancer survivorship becomes crucially important in developing effective support programs for patients (Hibbard & Cunningham, 2008). One area of cancer survivorship, symptom management, requires significant work and input from survivors.

Self-advocacy is increasingly recognized by providers, researchers, and policymakers as a means of increasing the capacity for patient-centered care. As often as self-advocacy is quoted as a desirable patient characteristic, little definition or clarification is provided, leaving this concept dramatically oversimplified and misrepresented in clinical practice and research (Sinding, Miller, Hudak, Keller-Olaman, & Sussman, 2012). However, the idea of promoting self-advocacy has face validity for helping patients with cancer navigate their disease trajectory (Walsh-Burke & Marcusen, 1999) and has potential value for improving symptom management, healthcare use, and quality of life, as demonstrated in noncancer populations (Brashers, Haas, & Neidig, 1999). Because of self-advocacy’s understudied but frequently referenced potential to improve the lives of cancer survivors, a thorough analysis of the concept from the perspective of the patient with cancer is necessary. Understanding how and why survivors advocate for themselves and the impact of self-advocacy on their ability to manage symptoms can influence how healthcare providers support survivors and facilitate patient engagement and empowerment. Female cancer survivors have distinctive experiences of self-advocacy because of their unique cancer-related symptoms and their gender-specific experiences of health care (Greimel & Freidl, 2000; Miaskowski, 2004; Street, 2002). Patients with ovarian cancer, in particular, are in high need of advocacy regarding symptom management because of their high symptom burden, intensity of treatment options, and frequency of recurrence (Donovan, Hartenbach, & Method, 2005; Elit et al., 2010). Therefore, one of the purposes of this study is to address these shortcomings in the definition of advocacy by using a qualitative approach to understand and describe the experience of self-advocacy from the perspective of female survivors. Findings will help guide future conceptualizations in research, practice, and policy.

Background

Ovarian cancer is responsible for 50% of all deaths from gynecologic cancer in the United States, with 22,280 new cases of and 15,500 deaths from ovarian cancer estimated in 2012 (American Cancer Society, 2012). On average, women on active treatment experience 12 concurrent symptoms, many of which are severe and poorly controlled (Donovan et al., 2005; Wenzel et al., 2002). Common symptoms among women with ovarian cancer include fatigue, pain, peripheral neuropathy, bowel disturbances, sleep problems, and memory concerns. This high symptom burden, along with often late-stage diagnosis, aggressive surgery and chemotherapy, and fear and uncertainty because of a high rate of recurrence, requires expert symptom management to maintain the patient’s quality of life.

Several symptom management interventions have attempted to increase patients’ abilities to manage their symptoms, although the success of these interventions varies widely (Badger, Segrin, Meek, Lopez, & Bonham, 2005; Bakitas et al., 2009; Given et al., 2010; Heidrich et al., 2009; Lee, Chiou, Chang, & Hayter, 2011; Sherwood et al., 2005; Sikorskii et al., 2007). It has been argued that the success of symptom management interventions may depend on a patient’s ability to advocate for him or herself by recognizing, communicating, and acting to improve the symptoms (Donovan et al., 2005; Hibbard, Stockard, Mahoney, & Tusler, 2004).

The concept of self-advocacy refers to a distinct type of advocacy in which an individual or group supports and defends their interests either in the face of a threat or proactively to meet their needs. Originating and extensively studied within the adolescent, disability, and HIV/AIDS populations, this concept was adopted by the field of cancer survivorship and is largely touted by practitioners, federal agencies, and researchers as an important skill for cancer survivors to have (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Hewitt et al., 2006; Hoffman & Stovall, 2006; Walsh-Burke & Marcusen, 1999). However, a lack of clarity on what self-advocacy is and what factors support it prevents organized understanding and application of the concept. As a result, the concept is largely unexamined and discourse is disjointed. Without a conceptual understanding, universal operationalization necessary for research and clinical practice is not possible.

A concept analysis by Hagan and Donovan (2012) identified self-advocacy in cancer survivorship as an internalization of key antecedent characteristics, skills, and resources into essential cognitions (creating a new normal, prioritizing needs and wants, and having a sense of empowerment), actions (navigating the healthcare system, building teamwork with healthcare teams, and engaging in mindful nonadherence), and supports (seeking and providing support and advancing cancer awareness and policies) to meet the challenges of cancer. However, to date, self-advocacy within the context of symptom management has not been studied, nor has the perspective of female cancer survivors been adequately captured.

Therefore, another purpose of this study is to explore self-advocacy among patients with ovarian cancer who are experiencing cancer-related symptoms and begin to identify factors associated with self-advocacy. This study will inform and enrich the concept of self-advocacy by using a phenomenologic methodology of exploring survivors’ understanding of what self-advocacy is, how and why they do or do not self-advocate, and what helps or hinders them in that process.

Methods

Design

Focus groups combined with in-depth interviews were used in this qualitative study to explore the experiences of women with ovarian cancer regarding symptom management and self-advocacy. Focus group sessions were conducted in a private, secluded meeting room of a café in Pittsburgh, PA. In-depth interviews were conducted via telephone with five participants (one from each focus group) one to five months after the focus group meetings to provide an in-depth explanation of individuals’ experiences described during focus group sessions.

A focus group allows individual experiences to inform the understanding of an abstract concept such as self-advocacy. Findings help develop an emergent theoretical and conceptual definition of what this phenomenon means in the context of female cancer survivors’ lives, including how they understand it, if and how they experience it, and the challenges and benefits of participating in it. A group context of well-structured and systematically analyzed focus groups is congruent with phenomenologic research and actually stimulates conversation with the possibility for new perspectives to arise (Bradbury-Jones, Sambrook, & Irvine, 2009). The qualitative rigor of this study is addressed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Qualitative Rigor

| Criterion | Application |

|---|---|

| Credibility | Training each reviewer in the qualitative methods of Morse (2008) and Saldana (2009) Debriefings between observers and principal investigator (PI) after each focus group Individual interviews, which increased engagement with key informants Constant comparison method of Morse (2008) Triangulation of transcripts, observer field notes, PI observations, and individual interview notes |

| Transferability | Broad sampling of women of various ages, disease statuses, and stages at diagnosis who described and endorsed similar definitions, themes, and subthemes of self-advocacy Thick description with exemplar quotations used to illustrate each subtheme Findings reflect a literature synthesis and content analysis of self-advocacy among cancer survivors conducted by the PI. |

| Dependability | Triangulation (see credibility) Audit trail of raters’ codes from each focus group, observers’ field notes, PI’s observations, and meeting notes after each rater meeting Member checking of final themes and subthemes by all participants PI used phenomenologic bracketing technique in an attempt to eliminate biases regarding the literature and personal beliefs. |

| Adequacy of data | Enough data collected until saturation achieved |

| Multiple raters | Two independent, trained raters separately coded each transcript. |

| Confirmability | Audit trail (see dependability) |

Participants

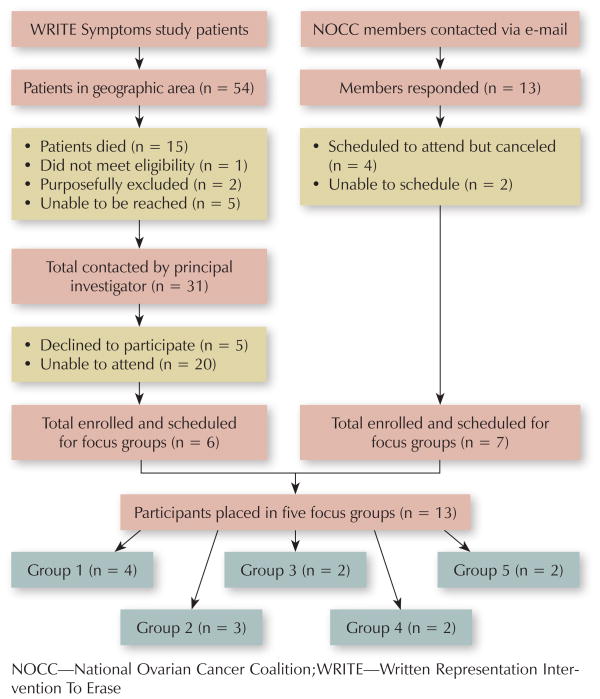

Participants were identified through an ongoing randomized clinical trial of the Written Representation Intervention To Erase (WRITE) Symptoms Web-based symptom management intervention and through the Pittsburgh chapter of the National Ovarian Cancer Coalition (NOCC). To maintain a broad sample of survivors, including a variety of stages at diagnosis and time since diagnosis, all women with a history of ovarian cancer were eligible to participate. Women known to be close to death by the WRITE Symptoms staff were not contacted to participate. Figure 1 provides more information on sampling and accrual. Of the overall sample, six women were recruited from the WRITE Symptoms study and seven were recruited from NOCC.

Figure 1.

Participant Recruitment Flow Chart

Procedures

Recruitment

The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol prior to recruitment. As mentioned, potential participants were recruited from the WRITE Symptoms study and the Pittsburgh chapter of NOCC.

Focus groups

The lead author was trained in Krueger and Casey’s (2009) focus group methodology by a qualitative expert from the School of Nursing at the University of Pittsburgh and led each focus group session. Throughout all prior contact and during each focus group, the lead author attempted to build rapport with each participant by using active listening skills and creating a welcoming, calm environment in which participants were encouraged to openly discuss their experiences and reflections of self-advocacy and symptom management. In accordance with Husserl’s phenomenologic epoché technique (Cohen, 1987; Husserl, 1970), the lead author attempted to fully bracket or purposefully set aside any preconceptions, biases, and assumptions about self-advocacy from the literature and personal beliefs prior to each contact with participants to allow the women’s lived experiences to guide the conversation. The lead author stressed that the women were the experts and that she was present to learn from their experiences and, consequently, would speak sparingly and rely on the women to exchange their experiences and direct the focus group conversation.

Focus groups were held within a private, secluded room at a local café. This setting was selected to provide an open, informal, nonclinical setting in which women could reflect on their previous experiences. Food and drinks were provided to facilitate building a relaxed environment. The first author sat at a table with participants. Each participant was given a copy of the three research questions, a blank pad of paper and pen to make notes, and cue cards with “self-advocacy” written on them to remind the women of the focus of the discussion. The questions were

How do you go about trying to manage your symptoms?

What does the word “self-advocacy” mean to you?

Is there anything more you can tell me about self-advocacy or the process of managing your symptoms that you think I should know?

Prior to each focus group meeting, the women consented to participate with assurance of the anonymity and confidentiality of all data in the focus group, interview, and validation phases. Observers (predoctoral students and nurse researchers) were introduced to the participants and sat outside the table, listening and taking notes on the environment, body language, and tone of conversation.

A series of three open-ended questions were read aloud by the author for group discussion and conversation between participants was encouraged by the lead author through nonjudgmental body language and allowance of silence between participants’ responses. Questions were intentionally broad and open-ended to invite participants’ interpretation and encourage personal perspectives on the phenomena of interest. Focused questions were used to clarify or guide the discussion when necessary for understanding. Focus groups lasted 60–90 minutes. Recordings of the focus groups were transcribed by a nursing student and the lead author, checked by the lead author for accuracy with the observers’ notes, and entered into NVivo, version 9, a computer program for data management.

In-depth interviews with the five selected participants were conducted one to five months after the focus groups met and included questions requesting clarification and elaborations of specific experiences participants mentioned during the focus group, such as their decisional process for stopping treatment. The five participants were selected as key informants based on their personal reflections and/or descriptions of challenges of self-advocating during the focus group. The PI called each participant at a convenient time and asked specific questions based on their comments during the focus group meeting to uncover a deeper description of the phenomenon. The in-depth interviews lasted 30–50 minutes.

The validation phase consisted of mailing or e-mailing all 13 participants a one-page summary of the combined major themes and subthemes across all focus groups. Participants filled in a three-item survey with “yes” or “no” questions asking if they agreed with the results from their personal experience and from their focus group experience. An additional open-ended question asked participants if they would make any change to the themes and/or subthemes and what those changes would be. All participants were given $10 gift cards after they completed the focus group and validation phases. The five participants who completed in-depth interviews were given an additional $10 after completion the interview.

Data Analysis

Demographic and disease information was summarized using descriptive statistics. Content analysis of all qualitative data followed an iterative constant comparison approach using axial coding techniques from Strauss and Corbin (1990). The researchers individually reviewed and coded each focus group transcript.

Themes (the essence of the phenomena or abstracted entities that provide meaning and identity to the phenomena) and subthemes (a unit of information composed of events, happenings, or instances) were extracted from transcripts, discussed, and agreed on by the authors using an iterative process (Morse, 2008). Disagreements between the two authors were resolved through discussion and consensus. Saturation of themes and subthemes was reached after the final focus group.

In-depth interviews were reviewed for consistency with focus group findings. All returned validation sheets (n = 13) indicated agreement with the themes and subthemes. Final themes and categories were reviewed by the authors to ensure they were consistent, comprehensive, mutually exclusive, and representative of the focus group, in-depth interview, and validation findings.

Findings

The average age of participants was 51.31 years, with a range of 26–69 years, comparable to the national average of women with ovarian cancer (U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2012). The majority was Caucasian (n = 12, 92%), married (n = 6, 46%), had at least an associate’s degree (n = 10, 77%), and had family incomes greater than $40,000 per year (n = 7, 54%). Six women (46%) were working full- or part-time jobs, three (23%) were retired, and three (23%) were on health-related disability or unable to work because of illness.

Women represented a variety of illness stages: Two women (15%) were currently receiving primary treatment, six women (46%) were receiving treatment for recurrent disease, and five women (39%) had no evidence of disease. Of the women in the recurrent phase, four had two or more recurrences. During the time of the focus group, eight participants (61%) were receiving treatment. Symptoms most often described during the focus groups included nausea, fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, and hair loss (discussed in all five focus groups) and depression and anxiety (discussed in three of five groups).

Themes and Subthemes

Major findings of this qualitative study are reported as the themes and subthemes abstracted from the focus groups, in-depth interviews, and participant validation. Women’s experience clustered into two major themes: (a) knowing who I am and keeping my psyche intact, and (b) knowing what I need and fighting for it. Both contained three subthemes.

Knowing who I am and keeping my psyche intact

The first theme demonstrates the intense internal process survivors engage in to advocate for themselves (see Table 2). Women’s ability to participate in the management of their many symptoms was related to their ability to maintain a confident, hopeful perspective about their cancer. Having a strong will (subtheme 1) summarized the motivation to stick with the arduous and ongoing demands of cancer treatment, survivorship, and symptom management. Women described this “will” as a determination to work to avoid death and fight for their survival. Keeping a positive attitude (subtheme 2) was mentioned by almost every woman, and described as a method of avoiding the negative aspects of their symptoms and fears of recurrence and death. Despite the collective belief in the importance of positive attitude, several women emphasized that attitude was not a sufficient means of keeping their cancer under control, but perhaps a means of reframing and focusing on what was good in their lives and what would help them deal with the challenges of cancer. Lastly, women described a feeling of being on the tipping point (subtheme 3) of holding their psyche together or falling apart. One woman described her spiritual and emotional distress that she hid from others and how she sometimes broke down in private. Coupled with this was the recognition that these temporary breakdowns were a part of the process of coming to terms with a life with cancer.

Table 2.

Subthemes and Quotations From Theme 1: Knowing Who I Am and Keeping My Psyche Intact

| Subtheme | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Having a strong will | “Strong will would be the word. Because no matter what … we’re just fighting to survive.” “Living is hard enough as it is, you have to be determined.” “You do what you have to do to get by, to get through it, to get to the end and not the end being underground.” |

| Keeping a positive attitude | “As soon as you go and put yourself in that negative mode, the cancer’s going to take over. So that’s how I get myself back out of it.” “I can’t sit here and wallow in self-pity because then I start getting depressed and, if I get depressed, I don’t do things, I can’t help my kids. I mean, I just can’t do anything.” |

| Being on the tipping point | “I’m just getting through it…. You don’t know what I’m doing behind the scenes and when I have my ‘boo-hoo’ times or when I’m kneeling beside the couch and I’m praying.” “You fake everybody out! You sit there and you act like everything’s fine but you’re scared.” |

Knowing what I need and fighting for it

The second theme expresses the women’s tenacity in seeking information, support, and teamwork to improve their symptoms (see Table 3). Knowing how and when to seek out information (subtheme 1) was key to this process. Although women reported receiving symptom management advice from healthcare providers, advocacy organizations, friends, and the Internet, they eventually discovered how to filter and manage the information to meet their needs and to support their symptom management goals.

Table 3.

Subthemes and Quotations From Theme 2: Knowing What I Need and Fighting for It

| Subtheme | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Knowing how and when to seek out information | “Knowledge is power, some of it you can handle and some of it you just can’t.” “They’re going to put me on this new inhibitor program and I’m reading more about it; I got all the details on it.” “You just want to be reassured all the time. ‘Nope, nothing in there…. Your numbers are good.’ I just needed that assurance. And now I don’t need that anymore.” |

| Being proactive to manage the healthcare team | “Any health issues, I get up there right away whether it’s a pain in my back, or you know, something with my eyes or whatever, you just [say] ‘Okay, here’s what we’re going to do, here’s what we’re not going to do,’ and that’s just it. And … I weigh options, of course.” “You don’t have to be the most intelligent person in the room but you have to know what’s best for you, and you have to find medical staff that’s going to understand that and relate to that.” |

| Taking advantage of support networks | “It’s like you’re part of a club now that you don’t want to be in, but you’re there so you might as well help each other as much as you can.” “Early on, you need people around you saying ‘this is what you should do’.” “Quite honestly, what has helped me more than anything is when I stop focusing on me and I start focusing on somebody else.” |

Women reported being proactive to manage the healthcare team (subtheme 2) by first recognizing their own priorities, beliefs, and values, and then using those as standards by which to make choices regarding their treatment and care. Women often described instances of self-advocacy as making informed, deliberate decisions to reduce their chemotherapy dosage or not take medications because of unwanted side effects. Women agreed that this ability developed during the course of survivorship, with newly diagnosed survivors less likely to be able to recognize opportunities for choices and less confident in speaking up with their healthcare team.

Finally, women were taking advantage of support networks (subtheme 3). Support networks provided invaluable outlets for women to learn how to advocate for themselves and to offer camaraderie to others learning how to advocate to improve their cancer- and treatment-related symptoms. Spoken of as a club or team, survivors depend on having informal groups of fellow survivors, family, and friends to learn the process of symptom management, including who to call and how to find out what their providers do not tell them. One woman, who identified herself as not a “touchy-feely” personality, described the intense connections she felt with women in her treatment rooms and support groups. Women often mentioned drawing strength from their family members, particularly their children, as a motivation for engaging in symptom management practices so that they could have increased quality of life with their family. Others talked about “sucking it up” with respect to chemotherapy-related symptoms to stay on treatment in the hopes of extending their lives. Five mothers of young children described their process of self-advocacy as “fighting for all you’re worth” to fulfill their role as a mother and their need to see their children grow up.

Overall, women experienced self-advocacy as requiring knowledge of self and needs to stand up for their preferences in symptom management. Advocating for oneself was defined as an attitude (strong will), a duty (personal responsibility), and something that evolves within an individual survivor as she realizes who she is and what she needs. Self-advocacy reflected the highly individualized contexts in which women advocate for their needs and values. For example, one woman described herself as a self-advocate because she negotiated a treatment plan with her oncologist that fit her needs, whereas another identified herself this way because she was able to put her symptom management needs above the needs of her family members.

Discussion

The lived experience of female cancer survivors’ experiences of self-advocacy and symptom management has not, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, previously been heard. The themes identified in this focus group study of women living with and managing symptoms highlight the complexities of women’s experience of self-advocacy. Although managing symptoms involves seeking out information, identifying management strategies, and working as a team with healthcare providers and fellow survivors, living with symptoms encompasses women’s attitudes, emotions, and psychological adjustments to being a cancer survivor and facing mortality. Balancing these distinct areas required women to constantly be negotiating symptom management as it relates to their physical, mental, and social well-being.

Women’s descriptions indicate that self-advocacy requires a survivor to define her personal preferences, weigh risks and benefits of treatment and management strategies based on her own priorities, and take initiative with her healthcare team to ensure they are meeting her needs. Women discussed problems and frustrations in trying to receive proper information and support from their healthcare providers, particularly noting a lack of clear symptom management recommendations.

A systematic review of the literature and concept analysis of cancer self-advocacy defined the concept of self-advocacy as a process of internalizing personal characteristics, learned skills, and formal support that allows survivors to act on their own behalf. Only after this internal process occurs can specific acts of self-advocacy occur (i.e., creating a new normal, making medical decisions based on personal values, negotiating with the healthcare team, and working with advocacy groups). This model of self-advocacy is reflected in the themes and voices of the women in the focus groups. Simply knowing how to manage and live with their symptoms was not enough for women; they had to internalize those abilities and, in so doing, infuse their personal values and beliefs into their symptom management processes. This deeply personal, critical reflection aimed at overcoming an obstacle is the essential element of self-advocacy and what differentiates this understudied concept from other behavioral concepts (e.g., self-efficacy, self-empowerment) (Richard & Shea, 2011).

Self-advocacy has gained much support from the clinical, research, and policy circles in cancer survivorship. LIVESTRONG (Shapiro et al., 2009), the Institute of Medicine (Hewitt et al., 2006), and a plethora of cancer advocacy organizations (Clark & Stovall, 1996; Hoffman & Stovall, 2006) recognize self-advocacy as a high-priority research and clinical imperative. Most efforts to promote self-advocacy among cancer survivors have focused on enhancing the communication, health literacy, and decision-making skills of survivors without addressing the patients’ internal needs, beliefs, and goals in understanding their disease and overcoming the obstacles it presents (Walsh-Burke & Marcusen, 1999).

Findings from the current study add to these efforts by providing a rich description and analysis of the lived experiences of self-advocacy among female cancer survivors. The major themes and subthemes can guide future research into self-advocacy and may represent potential targets for intervention to promote self-advocacy among women with ovarian cancer struggling with multiple symptoms.

Limitations

Recruitment issues arose early in the study, as many women were unable to schedule a time despite a desire to participate. The most common reasons given included cancer and disease burden (severe side effects and work and family scheduling issues). In addition, the audio recording from the fifth focus group was unable to be transcribed, although both authors were present at the gathering and discussed the findings directly after the focus group; both participants in that focus group validated the final findings. This sample represents a small, well-educated sample of ovarian cancer survivors likely to be less ill than survivors unable to attend the focus groups. However, women with various disease histories, stages at diagnoses, and current treatment provided for ample variation reflective of the broader ovarian cancer population and settings.

Implications for Nursing

Nurses and other oncology professionals can use the findings in both clinical and research capacities as ways of understanding how best to provide patient-centered support throughout the survivorship continuum. Although not included in the major themes of the focus groups, a noteworthy finding was that participants repeatedly mentioned the importance of knowledgeable, compassionate, skilled nurses in supporting their ability to self-advocate. Comfort in discussing symptoms with nurses allowed women to ask questions, seek support, and problem-solve about their symptoms. Women’s trust in nursing further exemplified the key role for nurses in supporting cancer survivors’ abilities to self-advocate.

Nursing upholds patient advocacy as a core responsibility (American Nurses Association, 2001). However, clinicians and researchers recognize that the ability to advocate for the needs and values of patients depends on patients’ abilities to recognize and name their priorities and how healthcare providers can support them. In addition, with survivorship extending beyond treatment to end of life, survivors often will be required to process evolving challenges on their own, outside of the traditional clinical setting. Therefore, a nurse’s duty to advocate on behalf of a patient is complimented and enhanced with a patient population capable of advocating for themselves.

Conclusions

This study provides a novel definition of self-advocacy from the lived experience of ovarian cancer survivors. By providing main themes and subthemes of how female survivors advocate for themselves, the findings add rich understanding and beginning conceptualizations of how women recognize their needs as survivors and then go about attaining them. Future research is needed to identify women at risk for poor self-advocacy and to develop interventions to support the unique processes women with cancer undergo in becoming advocates for themselves.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided through two University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing grants (#R01 NR010735 and #T32 NR0111972) and the Judith A. Erlen Nursing PhD Student Research Award.

Footnotes

For permission to post online, reprint, adapt, or reuse, pubpermissions@ons.org.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures, 2012. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association. The code of ethics. 2001 Retrieved from http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/EthicsStandards/CodeofEthicsforNurses.

- Badger T, Segrin C, Meek P, Lopez AM, Bonham E. Profiles of women with breast cancer: Who responds to a telephone counseling intervention. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2005;23(2–3):79–99. doi: 10.1300/j077v23n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, Ahles TA. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C, Sambrook S, Irvine F. The phenomenological focus group: An oxymoron? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65:663–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brashers DE, Haas SM, Neidig JL. The patient self-advocacy scale: Measuring patient involvement in health care decision-making interactions. Health Communication. 1999;11:97–121. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1102_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The national action plan for cancer survivorship. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivorship/what_cdc_is_doing/action_plan.htm.

- Clark EJ, Stovall EL. Advocacy: The cornerstone of cancer survivorship. Cancer Practice. 1996;4:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MZ. A historical overview of the phenomenologic movement. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1987;19:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1987.tb00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan HS, Hartenbach EM, Method MW. Patient-provider communication and perceived control for women experiencing multiple symptoms associated with ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005;99:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elit L, Charles C, Dimitry S, Tedford-Gold S, Gafni A, Gold I, Whelan T. It’s a choice to move forward: Women’s perceptions about treatment decision making in recurrent ovarian cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:318–325. doi: 10.1002/pon.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Given CW, Given BA, Sikorskii A, You M, Jeon S, Champion V, McCorkle R. Deconstruction of nurse-delivered patient self-management interventions for symptom management: Factors related to delivery enactment and response. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40:99–113. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9191-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greimel ER, Freidl W. Functioning in daily living and psychological well-being of female cancer patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;21:25–30. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan TH, Donovan HS. Self-advocacy and cancer survivorship: A concept analysis. 2012. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidrich SM, Brown RL, Egan JJ, Perez OA, Phelan CH, Yeom H, Ward SE. An individualized representational intervention to improve symptom management (IRIS) in older breast cancer survivors: Three pilot studies [Online exclusive] Oncology Nursing Forum. 2009;36:E133–E143. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E133-E143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Cunningham PJ. How engaged are consumers in their health and health care, and why does it matter? Research Briefs. 2008;8:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Service Research Journal. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B, Stovall E. Survivorship perspectives and advocacy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:5154–5159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husserl E. Logical investigations. New York, NY: Humanities Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MO. The shifting landscape of health care: Toward a model of health care empowerment. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:265–270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.189829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Chiou PY, Chang PH, Hayter M. A systematic review of the effectiveness of problem-solving approaches toward symptom management in cancer care. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011;20(1–2):73–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C. Gender differences in pain, fatigue, and depression in patients with cancer. Journal of National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2004;32:139–143. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Confusing categories and themes. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:727–728. doi: 10.1177/1049732308314930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2011;43:255–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro CL, McCabe MS, Syrjala KL, Friedman D, Jacobs LA, Ganz PA, Marcus AC. The LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center of Excellence Network. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2009;3:4–11. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood P, Given BA, Given CW, Champion VL, Doorenbos A, Azzouz F, Monahan PO. A cognitive behavioral intervention for symptom management in patients with advanced cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32:1190–1198. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.1190-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorskii A, Given CW, Given B, Jeon S, Decker V, Decker D, McCorkle R. Symptom management for cancer patients: A trial comparing two multimodal interventions. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinding C, Miller P, Hudak P, Keller-Olaman S, Sussman J. Of time and troubles: Patient involvement and the production of health care disparities. Health (London) 2012;16:400–417. doi: 10.1177/1363459311416833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Street RL., Jr Gender differences in health care provider-patient communication: Are they due to style, stereotypes, or accommodation? Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;48:201–206. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States cancer statistics: 1999–2008 incidence and mortality web-based report. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh-Burke K, Marcusen C. Self-advocacy training for cancer survivors: The Cancer Survival Toolbox. Cancer Practice. 1999;7:297–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.76008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel LB, Donnelly JP, Fowler JM, Habbal R, Taylor TH, Aziz N, Cella D. Resilience, reflection, and residual stress in ovarian cancer survivorship: A gynecologic oncology group study. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:142–153. doi: 10.1002/pon.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]