Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate the impact of a moderate zinc deficiency and a high intake of polyunsaturated fat on the mRNA expression of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα), peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), and mitochondrial Δ3Δ2-enoyl-CoA isomerase (ECI) in the liver. Weanling rats were assigned to five groups (eight animals each) and fed semi-synthetic, low-carbohydrate diets containing 7 or 50 mg Zn/kg (low-Zn (LZ) or high-Zn (HZ)) and 22% cocoa butter (CB) or 22% safflower (SF) oil for four weeks. One group each was fed the LZ-CB, LZ-SF, or HZ-SF diet free choice, and one group each was fed the HZ-CB and HZ-SF diets in restricted amounts according to intake of the respective LZ diets. The LZ diets markedly lowered growth and zinc concentrations in plasma and femur. Hepatic mRNA levels of PPARα, PPARγ, and ECI were not reduced by the moderate zinc deficiency. Overall, ECI-mRNA abundance was marginally higher in the SF-fed than in the CB-fed animals.

Keywords: zinc deficiency, PPARα, PPARγ, enoyl-CoA isomerase, cocoa butter, safflower oil, liver, rat

Introduction

Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are ligand-activated nuclear transcription factors that function as key regulators of lipid metabolism.1,2 Long-chain fatty acids, in particular polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and their metabolites, have been shown to be potent endogenous ligands of PPARs.3–7 PPARs bind to their target DNA sequences after formation of heterodimers with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) as a binding partner.4,5,8 Both the PPARs and RXR contain zinc finger structures in their DNA-binding domain that are essential for the binding of the nuclear response elements in the promoter region of their target genes.9–11 Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) is the major subtype in the liver, where it plays a central role in the regulation of fatty acid degradation.1–3 Pparα-deficient mice exhibit defective mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and ketone body production, and fatty livers in response to starvation.12–14 Transcript levels of Pparα and of PPARα target genes encoding key enzymes of fatty acid oxidation, including the mitochondrial Δ3,Δ2-enoyl-CoA-isomerase (Eci1 or Dci) gene, have been reported to be depressed in the liver of Zn-deficient young rats.15,16 The enzyme Δ3,Δ2-enoyl-CoA-isomerase (EC 5.3.3.8) is needed for the conversion of 3-cis-and 3-trans-enoyl-CoA esters of unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) to the 2-trans-enoyl-CoA esters for continued degradation of unsaturated fatty acids in the β-oxidation cycle.17,18 PPARγ as a transcription factor regulates mainly adipocyte differentiation and lipid storage.19,20 Pparγ-mRNA levels of thoracic aorta have been found to be significantly higher in Zn-depleted mice than in Zn-adequate and Zn-supplemented animals.21

The aim of our study was to investigate the impact of a moderate dietary Zn deficiency and a high intake of PUFA on the expression levels of Pparα, Pparγ, and Eci1 in the liver of weanling rats. The dietary content of available carbohydrates was restricted to impose a distinct preponderance of fatty acids as energy source. Safflower (SF) oil was chosen as a source rich in PUFA, and cocoa butter (CB) as a fat source rich in saturated fatty acids.

Methods and Materials

Animals, experimental design, and diets

A total of 40 male Wistar rats (Harlan-Winkelmann, Borchen, Germany) with an initial live weight of 50.8 ± 0.2 g (mean ± SD) were randomly allocated to five treatment groups. They were fed one of four semi-synthetic diets that were supplemented with 7.0 or 50 mg zinc/kg as Zn sulfate. Both the low-Zn (LZ) and high-Zn (HZ) diets contained either 22% CB or 22% SF oil. The feeding protocol in the five groups was as follows: (1) LZ-CB, fed the LZ-CB diet free choice; (2) HZ-CBR, fed the HZ-CB diet in restricted amounts according to intake of the LZ-CB diet on the previous day; (3) LZ-SF, fed the LZ-SF diet free choice; (4) HZ-SFR, fed the HZ-SF diet in restricted amounts according to intake of the LZ-SF diet on the previous day; and (5) HZ-SF, fed the HZ-SF diet free choice. All animals had free access to demineralized water. They were housed individually in polycarbonate cages (stainless-steel metal grids) under controlled environmental conditions (22°C, 60% rel. humidity, 12-hour light–dark cycle, lights on at 7.00 hours). All experimental treatments of the rats followed established guidelines for the care and handling of laboratory animals. Approval was obtained by the Animal Protection Authority of the State (II 25.3-19c20/15c GI 19/3).

Table 1 presents the composition of the experimental diets. After preparation, they were stored at 4°C. All diets contained 3% soybean oil as a source of essential fatty acids, and 28% cellulose as a diluent to restrict the energy density to a level comparable with that in a similar previous study22 and in the AIN-93 diet for rodents.23 Using tabulated values of the dietary components,24 the metabolizable energy (ME) content of the diets was calculated as 15.7 kJ/g, fat accounting for 59% and carbohydrates (starch and sucrose) for 22% of the ME. According to analysis, Zn concentrations in the LZ-CB, LZ-SF, HZ-CB, and HZ-SF diets (five replicates per diet) averaged 7.4 (SD, 0.6), 7.4 (0.7), 50.0 (6.9), and 50.5 (3.1), respectively. Based on the fatty acid composition reported in food tables,24 UFA accounted for about 40 and 86%, and linoleic acid for about 8 and 72% of the total fatty acids in the CB and SF diets, respectively.

Table 1.

Composition of the experimental diets.

| INGREDIENT | (g/kg) |

|---|---|

| Egg albumen powder | 200 |

| Corn starch | 67 |

| Sucrose | 100 |

| Cellulose | 280 |

| Soybean oil | 30 |

| L-Lysine + L-methionine (1:1) | 3 |

| Mineral mix* | 70 |

| Vitamin premix† | 10 |

| Zinc premix‡ | 20 |

| Fat supplement¶ | 220 |

| Sum | 1000 |

Notes:

Mineral mix (per kilogram diet): 17.88 g CaHPO4 × 2H2O, 10.02 g KH2PO4, 6.08 MgSO4 × 7H2O, 6.44 g CaCO3, 1.65 g NaCl, 0.81 g Na2CO3, 248.9 mg FeSO4 × 7H2O, 76.9 mg MnSO4 × H2O, 31.4 mg CuSO4 × 5H2O, 9.6 mg KCr(SO4)2 × 12H2O, 2.4 mg CoSO4 × 7H2O, 2.2 mg NaF, 0.8 mg Na2SeO3 × 5H2O, 0.5 mg KI, 0.5 mg Na2MoO4 × 2H2O, and corn starch ad 70 g.

Vitamin premix (per kilogram diet): 1.80 mg all trans retinol, 27.5 μg cholecalciferol; 40 mg RRR-α-tocopheryl acetate, 5.0 mg menadione; 6.0 mg thiamin HCl, 8.0 mg riboflavin, 2.4 mg folic acid, 40 mg niacin, 30 mg Ca-pantothenate, 10.0 mg pyridoxine, 0.1 mg cobalamin, 100 mg ascorbic acid, 2.0 mg d-biotin, 1,100 mg choline chloride, 100 mg myo-inositol, and corn starch ad 10 g.

Zinc premix (per kilogram diet): LZ diets, 30.8 mg ZnSO4 × 7H2O, corn starch ad 20 g; HZ diets, 219.9 mg ZnSO4 × 7H2O, corn starch ad 20 g.

Cocoa butter (CB) or safflower (SF) oil.

After four weeks, ending with a 10–12-hour overnight food withdrawal (starting at 23.30 hours), the animals were anesthetized in a carbon dioxide atmosphere. They were killed and exsanguinated by decapitation. Blood was collected in heparinized tubes to prepare plasma. Liver and right femur were immediately excised from the carcasses and weighed. A segment of the central liver lobe was removed under sterile conditions and frozen in liquid nitrogen for later RNA extraction. Tissues were stored at −80°C.

Analytical Methods

Zinc concentrations

Diet samples, liver samples, and femur bone were wet-ashed with 65% (w/v) HNO3 for 16 hours, and diluted with aqua bidest for Zn analysis by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (Unicam, Type 701). Zn analyses were replicated at least twice per sample, and accuracy was checked by standard samples of known Zn content. Plasma Zn concentrations were determined by hydride atomic absorption spectrometry (PU 9400, Phillips, Kassel, Germany) after dilution with 0.1 M HCl (1:20, v/v).

Liver triglycerides and plasma β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB)

Hepatic triglyceride concentration was determined as described previously.22 Briefly, total lipids were extracted in hexane:isopropanol and analyzed for triglycerides by a colorimetric assay kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The concentration of BHB in plasma of five animals per diet group was determined in duplicate by an assay kit (Autokit 3-HB; Wako Chemicals GmbH, Neuss, Germany).

Expression of the target genes in the liver

Total RNA content was extracted from pooled liver samples (50 mg from two animals each, three separate pools per diet group) by the acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform procedure.25 All steps were performed at +4°C under RNase-free conditions. Denatured RNA was sedimented by centrifugation (30 minutes, 14,000 × g, 2°C). Final RNA pellets were washed twice with 1 mL 70% (v/v) ethanol, vacuum-dried, dissolved in H2O-diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) solution, and stored in portions at −80°C.

RNA concentration was determined spectrometrically at 260 and 280 nm against H2O-DEPC. Purity of the RNA preparation was confirmed by gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Two different commercial kits were used for the reverse transcription of the harvested liver RNA: kit A, RevertAid™ First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas GmbH, St. Leon-Rot, Germany), using the oligo(dT) 18-primer, and kit B, iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA), using random hexamer primers. The procedural steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplification of the first-strand cDNA (2.0 μL) was performed in volumes of 50 μL, which contained 5.0 μL 10 × PCR buffer in 20 mM MgCl2 (Fermentas), 3.8 μL 2 mM dNTP mix (Fermentas), 1.0 U Taq polymerase (5 U/μL; Peqlab), 2.5 μL each for the specific forward and reverse primers (10 μM; MWG Biotech-AG), and 34.0 μL H2O-DEPC. The nucleotide sequences of the primer pairs were Pparα (accession number NM_013196, NCBI), forward 5′-acgatgctgtcctccttgat-3′, reverse 5′-cttcttgatgacctgcacga-3′; peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparγ) (NM_013124, NCBI), forward 5′-gagtctgtggggataaagcatc-3′, reverse 5′-gcgggaaggactttatgtatga-3′; mitochondrial short-chain enoyl-CoA isomerase (Eci1, synonym Dci) (X61184 or NM_017306, NCBI), forward 5′-caggataatggcggacaact-3′, reverse 5′-tacacgtgcagggacttctg-3′; and glycerol aldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) (NM_017008, NCBI), forward 5′-acgggaagctcactggcatg-3′, reverse 5′-ccaccaccctgttgctgtag-3′. The cDNA (in 2 μL containing about 1 μg for kit A and 0.7 μg for kit B) was amplified for 26–32 cycles (MyCycler, Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.).

The PCR products were electrophoresed on 1.5% ethidium bromide agarose gel. A base pair standard (GeneRuler DNA Ladder Plus, Fermentas) was included in the gel electrophoresis to check the length of the fragments. The spots were documented by means of a ChemiImager with a CCD video system and AlphaEase imaging software (Central Biotechnology Unit of the Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany) and digitalized by the software package GelScan 5.1 (BioSciTec GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). The amount of mRNA of the target genes (background-corrected) was normalized to the Gapdh-mRNA content and expressed as relative units. The final data were expressed as a multiple of the lowest mean of the target gene to emphasize the differences in gene expression.

Statistical analyses

The results of the five treatment groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using the IBM SPSS package, version 19 for Windows. Homogeneity of variance was verified by the Levene test. The Tukey HSD procedure was applied for post hoc comparisons among the five groups, the level of significance being set at P < 0.05. Standard errors of the mean (SEM) are based on the residual error of one-way ANOVA. Gene transcription levels obtained by the two test kits (A and B) were averaged per liver pool sample before ANOVA, because both test kits delivered similar mean expression levels of the target genes as indicated by the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Pparα-mRNA, r = 0.95, P = 0.012; Pparγ-mRNA, r = 0.55, P = 0.334; Eci1-mRNA, r = 0.93, P = 0.021).

Results

Food intake and growth of the animals

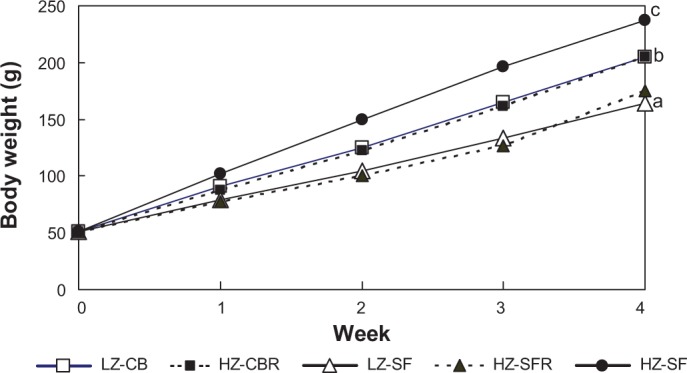

Food consumption in the three groups fed free choice was significantly affected by dietary Zn level and fat source (P < 0.001), and averaged 391, 277, and 428 g in LZ-CB, LZ-SF, and HZ-SF, respectively, during the four-week period. Final body weights of the weanling rats fed the LZ-CB and LZ-SF diets remained 14 and 31%, respectively, below that of the animals offered the HZ-SF diet free choice (P < 0.05; Fig. 1). Growth of the HZ-CBR and HZ-SFR groups, whose food allocation was restricted, was comparable to that of the animals fed the corresponding LZ diets free choice throughout the four-week period.

Figure 1.

Mean body weights of weanling rats fed different diets for four weeks.

Notes: Final body weights (week 4): significance of difference among diet groups by one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; pooled SEM = 4.9 g; a, b, c, mean values not sharing common letter significantly differ (P < 0.05; Tukey test).

Feeding protocol: LZ-CB, fed the LZ diet (7 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB free choice; HZ-CBR, fed the HZ diet (50 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-CB group; LZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice; HZ-SFR, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-SF group; and HZ-SF, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice.

Zinc status

Both dietary Zn level and fat source markedly affected plasma and femur Zn concentrations, whereas liver Zn concentrations remained closely comparable among diet groups (Table 2). Plasma Zn concentration of LZ-SF group was significantly lower than that of the LZ-CB group, and also significantly lower in the HZ-SFR than in the HZ-CBR group (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Zinc concentrations in plasma, femur, and liver of weanling rats fed different diets for four weeks.

| DIET GROUP | PLASMA Zn (μg/mL) |

FEMUR Zn (μg/g FRESH WT) |

LIVER Zn (μg/g FRESH WT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LZ-CB | 0.97b | 51b | 27.7a |

| HZ-CBR | 1.41d | 137d | 29.8a |

| LZ-SF | 0.63a | 39a† | 27.3a |

| HZ-SFR | 1.18c | 123c | 28.2a |

| HZ-SF | 1.08bc | 127cd | 29.2a |

| SEM‡ | 0.036 | 2.5 | 0.87 |

| P value¶ | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.258 |

Notes:

Means (n = 8) not sharing common superscript letters within columns significantly differ (P < 0.05; Tukey test).

n = 7.

Pooled standard error of the mean.

Significance of difference among diet groups by one-way ANOVA.

LZ-CB, fed the LZ diet (7 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB free choice; HZ-CBR, fed the HZ diet (50 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-CB group; LZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice; HZ-SFR, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-SF group; and HZ-SF, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice.

Plasma BHB and liver triglyceride concentrations

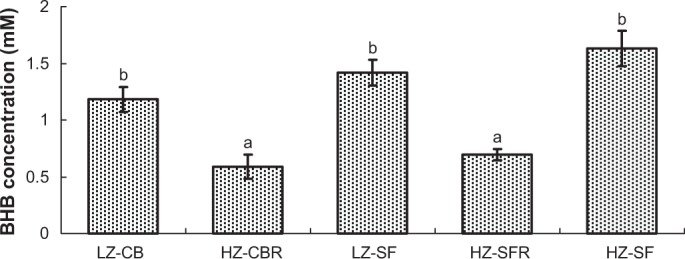

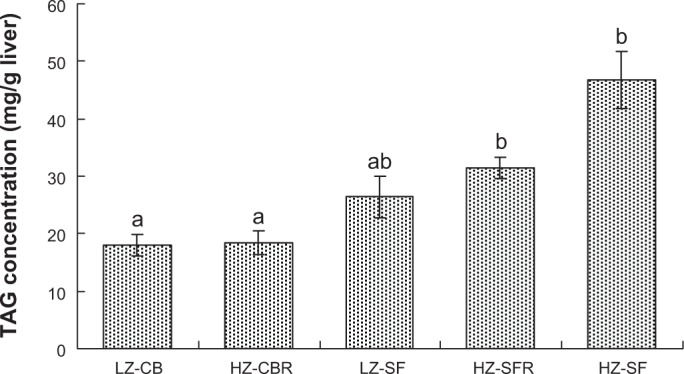

Plasma BHB concentrations at the end of the four-week experiment were approximately twofold (P < 0.05) lower in the HZ-CBR and HZ-SFR groups than in the three groups fed free choice (Fig. 2). Hepatic triglyceride (TAG) concentrations were not significantly altered by the dietary Zn supply (Fig. 3). Overall, the rats fed the SF diets displayed significantly higher TAG levels than those fed the CB diets (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Plasma BHB concentrations of weanling rats fed different diets for four weeks.

Notes: Plasma was obtained after an overnight food withdrawal for 10–12 hours (see the Methods and Materials section). Significance of difference among diet groups by one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001. error bars represent ± SEM (n = 5); a, b, means not sharing common letter significantly differ (P < 0.05; Tukey test after logarithmic transformation).

Feeding protocol: LZ-CB, fed the LZ diet (7 mg/kg diet) with 22% CB free choice; HZ-CBR, fed the HZ diet (50 mg/kg) with 22% CB in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-CB group; LZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice; HZ-SFR, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-SF group; and HZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice.

Figure 3.

Triglyceride (TAG) concentrations in the liver of weanling rats fed different diets for four weeks.

Notes: Significance of difference among diet groups by one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001. Error bars represent ± SEM (n = 8); a, b, means not sharing common letter significantly differ (P < 0.05; Tukey test).

Feeding protocol: LZ-CB, fed the LZ diet (7 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB free choice; HZ-CBR, fed the HZ diet (50 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-CB group; LZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice; HZ-SFR, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-SF group; and HZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice.

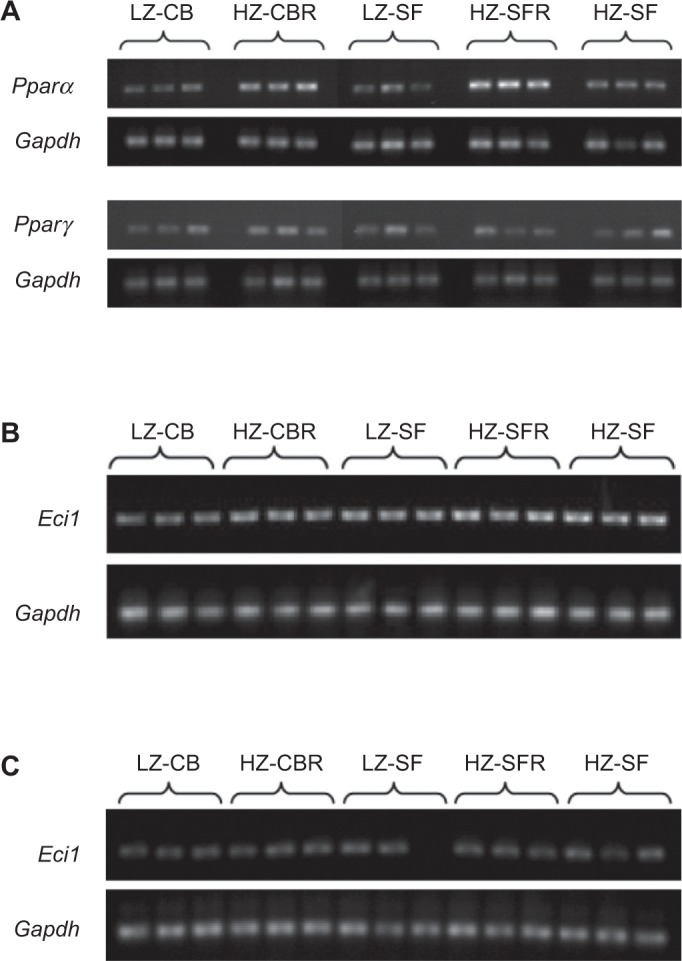

Gene expression of Pparα, Pparγ, and Eci1 in the liver

Figure 4 shows representative gel scans of the RT-PCR amplificates of the target genes in the liver of the five diet groups. The relative Pparα mRNA levels of the HZ-CBR and HZ-SFR groups were more than twice as high as those of the corresponding LZ group and the HZ-SF group fed free choice (Table 3). Pparγ transcript levels did not significantly differ among the five diet groups. Eci1-mRNA abundance was not significantly affected by the dietary Zn level, but there was a 1.6-fold difference between the LZ-CB and the HZ-SF groups (P < 0.05), suggesting a significant difference in response to the dietary fat source.

Figure 4.

Ethidium bromide fluorescence of the RT-PCR amplificates: (A) Pparα (test kit A) and Pparγ (test kit B), (B) Eci1 (test kit A), and (C) Eci1 (test kit B) together with the respective scans of Gapdh (see Analytical Methods section).

Feeding protocol: LZ-CB, fed the LZ diet (7 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB free choice; HZ-CBR, fed the HZ diet (50 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-CB group; LZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice; HZ-SFR, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-SF group; and HZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice.

Table 3.

Relative mRNA expression of Pparα, Pparγ, and mitochondrial Δ3, Δ2-enoyl-CoA-isomerase (Eci1) in the liver of weanling rats fed different diets for four weeks (combined analysis of two test kits; see the Analytical Methods section).

| DIET GROUP | Pparα | Pparγ | Eci1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LZ-CB* | 1.00a | 1.00a | 1.00a |

| HZ-CBR | 2.25b | 1.47a | 1.31ab |

| LZ-SF | 1.24a | 1.52a | 1.40ab |

| HZ-SFR | 2.68b | 1.52a | 1.36ab |

| HZ-SF | 1.24a | 1.55a | 1.60b |

| SEM† | 0.144 | 0.273 | 0.116 |

| Pvalue‡ | <0.001 | 0.599 | 0.050 |

Notes: Means (n = 3) not sharing common superscript letters within columns significantly differ (P < 0.05; Tukey test).

Lowest group mean value within group = 1.

Pooled standard error of the mean.

Significance of difference among diet groups by one-way ANOVA.

LZ-CB, fed the LZ diet (7 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB free choice; HZ-CBR, fed the HZ diet (50 mg Zn/kg) with 22% CB in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-CB group; LZ-SF, fed the LZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice; HZ-SFR, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil in restricted amounts according to intake in the LZ-SF group; and HZ-SF, fed the HZ diet with 22% SF oil free choice.

Discussion

Zn status

Depressed appetite and growth retardation are well-known early signs of alimentary Zn deficiency. Accordingly, the rats fed the LZ-CB and LZ-SF diets displayed markedly reduced food intakes as well as lower final body weights than those offered the HZ-SF diet free choice. There were, however, no conspicuous differences in the outer appearance of the animals other than body size. The deficient Zn status of the animals fed the LZ diets is clearly evident from the greatly reduced plasma and femur Zn concentrations relative to the values recorded for the animals consuming the HZ diets (Table 2). In the LZ-SF group, final body weights and Zn concentrations in plasma and femur were markedly lower (26, 35, and 23%, respectively) than in the LZ-CB group despite the same dietary Zn level, indicating an effect of fat source. It may be argued that the LZ-CB diet was consumed in higher amounts than the LZ-SF diet because of a preference for the CB-containing diet. This possibility, however, is not supported by the following observations. First, an interaction between dietary Zn level and fat type has been observed previously.22 Food intake, growth rate, and plasma Zn concentrations of weanling rats fed moderately Zn-deficient diets were reduced to a greater extent when their diet was enriched with sunflower oil as compared with beef tallow, whereas these diets were consumed in comparable amounts, and growth rates were comparable when the dietary Zn content was high.22 In support, numerous previous studies did not find a differential intake among Zn-adequate, high-fat (≥15%) diets supplemented with saturated versus unsaturated fats.22,26–29 Second, restriction of food intake per se does not lead to reduced plasma Zn concentrations. Plasma and femur Zn concentrations in the groups fed the HZ-SF diet either free choice or in restricted amounts were comparable (Table 2). This agrees with former studies showing that plasma or serum Zn concentrations are not altered when Zn-adequate diets are fed in restricted amounts as compared with ad libitum feeding.22,30–33 Finally, growth retardation because of an alimentary Zn deficit cannot be attributed to a loss of appetite as the primary cause. It has already been shown in 1970 that increasing the food intake of Zn-depleted young rats by force-feeding does not alleviate the growth arrest but instead quickly elicits severe signs of ill health and morbidity of the animals.34 Taken together, the evidence of the present study indicates a poorer Zn status of the rats fed the LZ-SF diet compared with those fed the LZ-CB diet despite comparable liver Zn concentrations, in agreement with previous studies.22,35 The underlying mechanism for this effect of fat source on Zn status awaits further research.

Gene expression and fatty acid metabolism

Fatty acids are an important energy source for the liver. The expression of hepatic genes coding for proteins and key enzymes involved in fatty acid catabolism in the liver is mediated by PPARα, the major PPAR transcription factor in hepatocytes.1–3 The expression of PPARα in the liver of rats and mice has been found to follow a diurnal rhythm.36–40 Oishi et al38 show that this circadian expression of Pparα is regulated directly by clock genes and is abolished in homozygous Clock mutant mice. But food plays a dominant role as a zeitgeber for circadian oscillations of gene expression in the liver and other peripheral tissues (see below).41 Pparα-mRNA must be translated first into its protein counterpart before it can serve its role as nuclear transcription factor and ultimately transactivate its numerous target genes, including those involved in lipid metabolism. In the liver of rats, PPARα protein levels closely followed the diurnal cycling of Pparα-mRNA levels suggesting an efficient translation of its mRNA.36 Yang et al42 also reported corresponding increases in the expression of PPARα at both the transcript and protein levels in the liver of Rheb1 null mice as a result of a pronounced decrease in food intake. These knockout mice exhibited increases in hepatic transcript levels of genes involved in β-oxidation and ketogenesis (including carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A, medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, and mitochondrial 3-hydroxy 3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase), and markedly elevated serum levels of BHB concentrations compared with normal control mice. These findings reflect responses at all levels of cell function from gene transcription in the nucleus to hepatic fatty acid catabolism. Activation of the transcriptional activity of PPARs is a highly complex regulatory process that involves ligand binding, release of corepressors, and binding of the nuclear receptor RXR and diverse coactivators.43–45 Recent studies suggest that natural ligands for PPARα in the liver are dietary and newly synthesized fatty acids,46,47 whereas plasma free fatty acids released by TAG lipolysis in adipose tissue activated hepatic PPARβ/δ.48 PPARα and PPARβ/δ presumably mediate the expression of similar target genes.48 The activated PPAR–RXR heterodimer binds to specific peroxisome-proliferator response elements (PPREs) of the target genes to initiate transcription. Functional PPREs have been identified for several of the targets of PPARα (including Cpt1A, Acadl, and Hmgcs2) but not for the auxiliary enzymes of UFA oxidation.2,49

In our study, the relative transcript levels of the Pparα gene in the liver of the rats fed the HZ CB and SF diets in restricted amounts were about twice as high as those in the animals fed the corresponding LZ diets free choice. This marked effect, however, cannot be attributed to the difference in dietary Zn supply. The Pparα-mRNA levels of the ad libitum-fed LZ-CB and LZ-SF groups were comparable to the level of the ad libitum-fed HZ-SF group, clearly indicating that the moderate Zn deficiency of the animals fed the LZ diets did not impair Pparα transcription. We instead conclude that the higher Pparα-mRNA abundance in the HZ-CBR and -SFR groups is the consequence of the feeding protocol. Both short-term starvation12,50,51 and chronic food restriction52,53 have been shown to alter hepatic PPARα expression. In agreement with our experiment, hepatic Pparα transcript levels in rats exposed to a 85% food restriction (12-hour light–dark cycle, but without restriction in time of food access) were about twofold higher after a 12-hour fasting period than in control animals fed the same diet free choice.53 Regarding our study, it must be considered that the restricted food allocation in the HZ-CBR and HZ-SFR groups caused the animals to adapt to a daytime feeding pattern. These rats had almost completely consumed their daily ration by 23.30 hours when food was removed for a 10–12-hour overnight fasting period before sacrifice at the end of the experiment. At that time, the animals fed free choice had eaten at most half of the amount of food that they had consumed on the previous day, thus imposing an unaccustomed metabolic stress on these animals because of the lack of food during their habitual night-time feeding. There was no difference in food intake pattern between the animals offered the Zn-deficient CB and SF diets and those receiving the HZ-SF diet free choice, which agrees with previous observations.54 I n rodents, as nocturnal animals who consume most of their food during the dark hours under a 12-hour light–dark cycle, Pparα-mRNA abundance in the liver reaches peak levels toward the end of the light phase, when energy homeostasis relies on fatty acid degradation and possibly on ketogenesis and gluconeogenesis, whereas nadir values are recorded at the beginning of the light cycle.36–40 This circadian rhythm has been shown to shift by approximately 12 hours when food access is restricted to daytime hours.39 Such a shift may have also occurred in the restrictedly fed rats of our study, and thus can explain the elevated Pparα transcript levels in these animals. This assumption is supported by plasma BHB concentrations (Fig. 2), which were approximately twofold higher in the ad libitum-fed rats than in the restrictedly fed animals, suggesting that the former animals were affected by the overnight food withdrawal to a greater extent than those accustomed to the habitual food shortage during the dark hours. Similarly, plasma ketone body concentrations after an overnight fast were about three times as high in Zn-deficient rats as in pair-fed control rats that had become meal eaters.55 Furthermore, rats that were continuously fed a Zn-supplemented diet showed much higher fasting plasma concentrations of free fatty acid than meal-eating rats.56

Previous studies15,16 found that the transcription levels of Pparα and of genes coding for proteins involved in fatty acid degradation, including the Eci1 gene, were markedly down-regulated in the liver of Zn-depleted young rats as compared with Zn-adequate control animals, whereas transcript levels of genes involved in de novo fatty acid synthesis were up-regulated along with increased hepatic TAG concentrations. These findings obviously conflict with our results, which indicate that the hepatic transcript levels of Pparα (Pparγ and Eci1 as well) were not reduced in the rats fed the LZ-CB and LZ-SF diets as compared with the animals fed the HZ-SF diet free choice. Prominent differences between our and the former studies15,16 concern diet composition, in particular zinc, carbohydrate, and fat content; and the feeding protocol. First, it could be argued that the rats offered the LZ-CB and LZ-SF diets were exposed only to a moderate Zn deficit, allowing considerable growth rates. Second, fat contributed about 60% and carbohydrates (starch and sucrose) only about 22% of ME intake in our study. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that hepatic de novo fatty acid synthesis was greatly depressed in our experiment. In support, in weanling rats fed very similar high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets, the hepatic activity of glucose-6- phosphate dehydrogenase, which belongs to the lipogenic enzyme family and closely correlates with the rate of fatty acid synthesis in the liver,57 was greatly reduced as compared with animals fed a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet.22 Third, the most decisive difference in the experimental protocols concerns the feeding regimen. In the former studies,15,16 the young rats were force-fed by intragastric tube to equalize the amount and frequency of intake of the Zn-deficient and Zn-supplemented diet. These diets were fed at a level (11.6 g dry matter/day) that exceeds amounts that Zn-depleted young rats have been observed to consume voluntarily,58 whereas the identical quantity of the Zn-adequate diet given to the control rats was evidently below the expected amount of free-choice intake and limited their weight gain to merely 2.4 g/d,15 a level that is about 40% below the gain (~4 g/d) in the LZ-SF group of our experiment at a similar body weight. Force-feeding of severely Zn-deficient diets above appetite is likely to stimulate energy storage, because the deficit of zinc inhibits cell division, nitrogen retention, and lean tissue growth.59–61 Hence, the metabolic response to forced overnutrition can be expected to induce lipogenesis and fatty livers, and induce a down-regulation of the transcription of Pparα and its target genes of the fatty acid oxidation pathway.62 In agreement with such a nutritional state, the livers of young rats force-fed Zn-deficient diets displayed markedly higher activities of lipogenic enzymes63 and increased triglyceride concentrations.58 In contrast, triglyceride concentrations in the liver of young rats offered Zn-deficient diets for voluntary consumption were not higher than in the liver of Zn-supplemented control animals fed ad libitum or restrictedly.22,58 In line with these former studies, hepatic TAG concentrations did not differ between the rats fed the LZ and HZ diets in our experiment (Fig. 3). On the other hand, chronic underfeeding is prone to enhance hepatic Pparα expression. In the liver of mice that were fed below appetite for seven days in a synchronized pair-feeding protocol (food access only during the 12-hour dark cycle before sacrifice the following morning), Pparα-mRNA abundance was more than threefold higher than in control animals receiving food ad libitum.52 Taken together, it may be presumed that the formerly observed marked difference in the transcription of Pparα and target genes encoding enzymes of fatty acid catabolism in the liver of force-fed Zn-deficient rats15,16 was not because of a deficit of zinc per se but instead was the consequence of feeding the Zn-deficient diet above and the Zn-supplemented diet below appetite of the animals, inducing metabolic states of over- and underfeeding, respectively.

Zinc is, beyond doubt, essential for the transcriptional activity of PPAR proteins. These nuclear transcription factors, and their heterodimeric binding partner RXR as well, contain Zn finger structures in their DNA-binding domain, which are critical for the polarity and specificity of the receptor element binding.10,11 The DNA-binding activity of PPARα and PPARγ proteins has been found to be impaired in cultures of Zn-deprived porcine vascular cells, and PPAR agonists could induce PPAR-binding activity only in Zn-sufficient cells.64 Furthermore, the DNA-binding activity of PPARγ was significantly reduced in the liver of Zn-deficient mice.21 The pivotal role of PPARα-mediated transcription of genes coding for proteins and enzymes involved in fat catabolism is clearly evident from studies with Pparα-null mice, which develop hypoglycemia, hypoketonemia, and fatty livers when they are exposed to starvation because of their inability to increase hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis.12–14 Similar metabolic symptoms have been observed in Eci1-deficient mice.65 Eci1 and Hmgcs2, the latter coding for the mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the hepatic synthesis of ketone bodies, are among the genes that are regulated by PPARα.2,14,49,66 In consideration of these metabolic findings, it can be hypothesized that an impaired transcriptional activity of the PPARα protein toward its target genes because of a deficit of zinc should adversely affect fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis in the liver, especially when fat is the preponderant source of energy and the intake of available carbohydrates is low as it was the case in our study. However, the metabolic evidence available from our experiment and that from previous research indicates that alimentary Zn deficiency does not compromise mitochondrial fatty acid degradation and ketogenesis. In our experiment, the hepatic Eci1-mRNA levels did not differ between the rats fed the LZ and HZ diets. This indirectly suggests that the activity of PPARα as nuclear transcription factor was not impaired by the mild Zn deficiency. Furthermore, plasma BHB concentrations after the overnight fasting period were comparable among the ad libitum-fed animals independent of the dietary Zn supply. In previous studies, severe Zn deficiency did not adversely affect fatty acid oxidation or ketogenesis. As early as in 1966, Theuer and Hoekstra67 reported that the oxidation of 14C-labeled palmitic acid administered to severely Zn-deficient weanling rats 14 hours after food withdrawal was not impaired as compared with Zn-adequate control animals. Also, the extent of β-oxidation of linoleic and α-linolenic acid, and serum BHB concentrations were higher in Zn-deficient pregnant and nonpregnant rats than in Zn-adequate control animals.68,69 Fasting plasma ketone body concentrations in Zn-depleted young rats were about three times as high as in Zn-supplemented pair-fed animals.55 Plasma BHB concentrations and oxidation of BHB in pregnant rats given a suboptimal zinc diet (6 μg Zn/g diet) were markedly higher than in Zn-sufficient controls.70 Both groups were in a negative energy balance because of the late stage of pregnancy, but there was no evidence of maternal hypoglycemia. Thus, our study is consistent with these former studies suggesting that zinc is not a critical nutrient in β-oxidation of fatty acids and ketogenesis.

In our experiment, the SF diet did not induce higher Pparα-mRNA levels than the CB diet despite a more than twofold higher intake of unsaturated fatty acids (predominantly linoleic acid). This finding agrees with previous studies showing that the transcription of the Pparα gene itself is much less responsive to the type of fatty acid intake than the transcriptional activity of the PPARα protein on its target genes.47,71,72 Remarkably, Eci1-mRNA levels were not related to Pparα-mRNA levels (r = 0.20, P > 0.05). Overall, the former were higher in the liver of the SF-fed animals, especially in the HZ-SF group (P < 0.05), than in the CB-fed groups, suggesting a moderate response to the dietary fat source. This agrees with previous studies reporting that rodents fed diets enriched with linoleic acid as compared with saturated fatty acids displayed elevated Eci1 transcript levels, even though the differences were not significant.73–75

In conclusion, the moderate Zn deficiency did not impair gene expression of Pparα, Pparγ, and Eci1 in the liver of weanling rats fed fat-enriched diets, in which CB and SF oil were the preponderant energy source (about 60% of the dietary ME). The observed elevated abundance of Pparα-mRNA in the restrictedly fed animals corroborates a sensitive response to changes in the feeding regimen. There was a notable increase in the hepatic Eci1 transcription in response to the SF oil-based diets. Plasma BHB levels suggest that β-oxidation of fatty acids and ketogenesis was not affected by the moderate Zn deficiency.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Andreas Müller for his advice in PCR methodology, to Dr. Erika Most for analytical help, and to Prof. Dr. Josef Pallauf and the ZBB unit for providing access to laboratory instruments.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

JJ and EW conceived and designed the experiment. JJ supervised the experiment and laboratory analyses. EW conducted the statistical analyses and wrote the draft of the manuscript. JJ made revisions in the Methods and Materials section. Both authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Joseph Zhou, Editor in Chief

FUNDING: The authors have no specific financial support or funding to report.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

DISCLOSURES AND ETHICS

As a requirement of publication the authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review The reviewers reported no competing interests

REFERENCES

- 1.Escher P, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: insight into multiple cellular functions. Mutat Res. 2000;448:121–38. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakhshandehroo M, Knoch B, Müller M, Kersten S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target genes. PPAR Res. 2010;20 doi: 10.1155/2010/612089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Göttlicher M, Widmark E, Li Q, Gustafsson JA. Fatty acids activate a chimera of the clofibric acid-activated receptor and the glucocorticoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4653–4657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Issemann I, Prince RA, Tugwood JD, Green S. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor:retinoid X receptor heterodimer is activated by fatty acids and fibrate hypolipidaemic drugs. J Mol Endocrinol. 1993;11:37–47. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0110037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller H, Dreyer C, Medin J, Mahfoudi A, Ozato K, Wahli W. Fatty acids and retinoids control lipid metabolism through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-retinoid X receptor heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2160–2164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kliewer SA, Sundseth SS, Jones SA, et al. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4318–4323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forman BM, Chen J, Evans RM. Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4312–4317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gearing KL, Göttlicher M, Teboul M, Widmark E, Gustafsson JA. Interaction of the peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor and retinoid X receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1440–1444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hihi AK, Michalik L, Wahli W. PPARs: transcriptional effectors of fatty acids and their derivatives. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:790–798. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8467-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee MS, Kliewer SA, Provencal J, Wright PE, Evans RM. Structure of the retinoid X receptor alpha DNA binding domain: a helix required for homodimeric DNA binding. Science. 1993;260:1117–1121. doi: 10.1126/science.8388124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu MH, Palmer CN, Song W, Griffin KJ, Johnson EF. A carboxyl-terminal extension of the zinc finger domain contributes to the specificity and polarity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27988–27997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kersten S, Seydoux J, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1489–1498. doi: 10.1172/JCI6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leone TC, Weinheimer CJ, Kelly DP. A critical role for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) in the cellular fasting response: the PPARα-null mouse as a model of fatty acid oxidation disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7473–7478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashimoto T, Cook WS, Qi C, Yeldandi AV, Reddy JK, Rao MS. Defect in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a-inducible fatty acid oxidation determines the severity of hepatic steatosis in response to fasting. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28918–28928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910350199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.tom Dieck H, Döring F, Roth H-P, Daniel H. Changes in rat hepatic gene expression in response to zinc deficiency as assessed by DNA arrays. J Nutr. 2003;133:1004–1010. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.tom Dieck H, Döring F, Fuchs D, Roth H-P, Daniel H. Transcriptome and proteome analysis identifies the pathways that increase hepatic lipid accumulation in zinc-deficient rats. J Nutr. 2005;135:199–205. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunau W-H, Dommes V, Schulz H. β-oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria, peroxisomes, and bacteria: a century of continued progress. Prog Lipid Res. 1995;34:267–342. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(95)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiltunen JK, Qin YM. β-oxidation—strategies for the metabolism of a wide variety of acyl-CoA esters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1484:117–128. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogue A, Spire C, Brun M, Claude N, Guillouzo A. Gene expression changes induced by PPAR gamma agonists in animal and human liver. PPAR Res. 2010;16 doi: 10.1155/2010/325183. doi: org/10.1155/2010/325183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu S, Matsusue K, Kashireddy P, et al. Adipocyte-specific gene expression and adipogenic steatosis in the mouse liver due to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ1 (PPARγ1) overexpression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:498–505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reiterer G, MacDonald R, Browning JD, et al. Zinc deficiency increases plasma lipids and atherosclerotic markers in LDL-receptor-deficient mice. J Nutr. 2005;135:2114–2118. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.9.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weigand E, Boesch-Saadatmandi C. Interaction between marginal zinc and high fat supply on lipid metabolism and growth of weanling rats. Lipids. 2012;47:291–302. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3629-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123:1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Souci SW, Fachmann W, Kraut H, editors. Food Composition and Nutrition Tables. 7th ed. Stuttgart: Medpharm Scientific Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercer SW, Trayhurn P. Effect of high fat diets on energy balance and thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue of lean and genetically obese ob/ob mice. J Nutr. 1987;117:2147–2153. doi: 10.1093/jn/117.12.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumamoto T, Ide Z. Comparative effects of α- and γ-linolenic acids on rat liver fatty acid oxidation. Lipids. 1998;33:647–654. doi: 10.1007/s11745-998-0252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimomura Y, Tamura T, Suzuki M. Less body fat accumulation in rats fed a safflower oil diet than in rats fed a beef tallow diet. J Nutr. 1990;120:1291–1296. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.11.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaqoob P, Sherrington EJ, Jeffery NM, et al. Comparison of the effects of a range of dietary lipids upon serum and tissue lipid composition in the rat. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;27:297–310. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(94)00065-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer TR, Briske-Anderson M, Johnson SB, Holman RT. Influence of reduced food intake on polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism in zinc-deficient rats. J Nutr. 1984;114:1224–1230. doi: 10.1093/jn/114.7.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneeman BO, Lacy D, Ney D, et al. Similar effects of zinc deficiency and restricted feeding on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in rats. J Nutr. 1986;116:1889–1895. doi: 10.1093/jn/116.10.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarz G, Pallauf J. Experimental zinc deficiency in growing rabbits and its influence on the zinc status of blood serum. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 1987;57:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koo SI, Lee CC. Effect of marginal zinc deficiency on lipoprotein lipase activities in postheparin plasma, skeletal muscle and adipose tissues in the rat. Lipids. 1989;24:132–136. doi: 10.1007/BF02535250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chesters JK, Quarterman J. Effects of zinc deficiency on food intake and feeding pattern of rats. Br J Nutr. 1970;24:1061–1069. doi: 10.1079/bjn19700109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weigand E. Fat source affects growth of weanling rats fed high-fat diets low in zinc. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2012;96:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2010.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemberger T, Saladin R, Vazquez M, et al. Expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene is stimulated by stress and follows a diurnal rhythm. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1764–1769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel DD, Knight BL, Wiggins D, Humphreys SM, Gibbons GF. Disturbances in the normal regulation of SREBP-sensitive genes in PPARα-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:328–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oishi K, Shirai H, Ishida N. CLOCK is involved in the circadian transactivation of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) in mice. Biochem J. 2005;386:575–581. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canaple L, Rambaud L, Dkhissi-Benyahya O, et al. Reciprocal regulation of BMAL1 and PPARα defines a novel positive feedback loop in the rodent liver circadian clock. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1715–1727. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang X, Downes M, Yu RT, et al. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell. 2006;126:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Damiola F, Minh NL, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2950–2961. doi: 10.1101/gad.183500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang W, Jiang W, Luo L, et al. Genetic deletion of Rheb1 in the brain reduces food intake and causes hypoglycemia with altered peripheral metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:1499–1510. doi: 10.3390/ijms15011499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burri L, Thoresen GH, Berge RK. The role of PPARα activation in liver and muscle. PPAR Res. 2010;11 doi: 10.1155/2010/542359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moreno M, Lombardi A, Silvestri E, et al. PPARs: Nuclear receptors controlled by, and controlling, nutrient handling through nuclear and cytosolic signaling. PPAR Res. 2010;10 doi: 10.1155/2010/435689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viswakarma N, Jia Y, Bai L, et al. Coactivators in PPAR-regulated gene expression. PPAR Res. 2010;21 doi: 10.1155/2010/250126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chakravarthy MV, Pan Z, Zhu Y, et al. “New” hepatic fat activates PPARα to maintain glucose, lipid, and cholesterol homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;1:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanderson LM, de Groot PJ, Hooiveld GJEJ, et al. Effect of synthetic dietary triglycerides: a novel research paradigm for nutrigenomics. PLoS One. 2008;3(2):e1681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanderson LM, Degenhardt T, Koppen A, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) but not PPARα serves as a plasma free fatty acid sensor in liver. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:6257–6267. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00370-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandard S, Müller M, Kersten S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a target genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:393–416. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Escher P, Braissant O, Basu-Modak A, Michalik L, Wahli W, Desvergne B. Rat PPARs: quantitative analysis in adult rat tissues and regulation in fasting and refeeding. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4195–4202. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanderson LM, Boekschoten MV, Desvergne B, Müller M, Kersten S. Transcriptional profiling reveals divergent roles of PPARα and PPARβ/δ in regulation of gene expression in mouse liver. Physiol Genomics. 2010;41:42–52. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00127.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sterchele PF, Sun H, Peterson RE, Vanden Heuvel JP. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α mRNA in rat liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;326:281–289. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takemori K, Kimura T, Shirasaki N, Inoue T, Masuno K, Ito H. Food restriction improves glucose and lipid metabolism through Sirt1 expression: a study using a new rat model with obesity and severe hypertension. Life Sci. 2011;88:1088–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reeves PG. Patters of food intake and self-selection of macronutrients in rats during short-term deprivation of dietary zinc. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:232–243. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(03)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quarterman J, Florence E. Observations on glucose tolerance and plasma levels of free fatty acids and insulin in the zinc-deficient rat. Br J Nutr. 1972;28:75–79. doi: 10.1079/bjn19720009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Florence E, Quarterman J. The effects of age, feeding pattern and sucrose on glucose tolerance, and plasma free fatty acids and insulin concentrations in the rat. Br J Nutr. 1972;28:63–74. doi: 10.1079/bjn19720008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salati SM, Amir-Ahmady B. Dietary regulation of expression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:121–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eder K, Kirchgessner M. Effects of zinc deficiency on concentrations of lipids in liver and plasma of rats. Trace Elem Electrolytes. 1996;13:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pallauf J, Kirchgessner M. Zinc deficiency as affecting the digestibility and utilization of nutrients. Arch Tierernähr. 1976;26:457–473. doi: 10.1080/17450397609426717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vallee BL, Falchuk KH. The biochemical basis of zinc physiology. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:79–118. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giugliano R, Millward DJ. The effects of severe zinc deficiency on protein turnover in muscle and thymus. Br J Nutr. 1987;57:139–155. doi: 10.1079/bjn19870017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Desvergne B, Michalik L, Wahli W. Transcriptional regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:465–514. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eder K, Kirchgessner M. Zinc deficiency and activities of lipogenic and glycolytic enzymes in liver of rats fed coconut oil or linseed oil. Lipids. 1995;30:63–69. doi: 10.1007/BF02537043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reiterer G, Toborek M, Hennig B. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors α and γ require zinc for their anti-inflammatory properties in porcine vascular endothelial cells. J Nutr. 2004;134:1711–1715. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.7.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Janssen U, Stoffel W. Disruption of mitochondrial β-oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids in the 3,2-trans-enoyl-CoA isomerase-deficient mouse. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19579–19584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodríguez JC, Gil-Gómez G, Hegardt FG, Haro D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor mediates induction of the mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase gene by fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18767–18772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Theuer RC, Hoekstra WG. Oxidation of 14C-labeled carbohydrate, fat and amino acid substrates by zinc-deficient rats. J Nutr. 1966;89:448–454. doi: 10.1093/jn/89.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cunnane SC, Yang J, Chen Z-Y. Low zinc intake increases apparent oxidation of linoleic and a-linolenic acids in the pregnant rat. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1993;71:205–210. doi: 10.1139/y93-032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cunnane SC, Yang J. Zinc deficiency impairs whole body accumulation of polyunsaturates and increases the utilization of [1-14C]linoleate for de novo lipid synthesis in pregnant rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;73:1246–1252. doi: 10.1139/y95-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greeley S, Sandstead HH. Oxidation of alanine and β-hydroxybutyrate in late gestation by zinc-restricted rats. J Nutr. 1983;113:1803–1810. doi: 10.1093/jn/113.9.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buettner R, Parhofer KG, Woenckhaus M, et al. Defining high-fat rat models: metabolic and molecular effects of different fat types. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;36:485–501. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hsu S-C, Huang CJ. Reduced fat mass in rats fed a high oleic acid-rich safflower diet is associated with changes in expression of hepatic PPARα and adipose SREB-1c-regulated genes. J Nutr. 2006;136:1779–1785. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.7.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ide T, Kobayashi H, Ashakumary L, et al. Comparative effects of perilla and fish oils on the activity and gene expression of fatty acid oxidation enzymes in rat liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1485:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takahashi Y, Kushiro M, Shinohara K, Ide T. Activity and mRNA levels of enzymes involved in hepatic fatty acid synthesis and oxidation in mice fed conjugated linoleic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1631:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martin PGP, Guillou H, Lasserre F, et al. Novel aspects of PPARα-medated regulation of lipid and xenobioti metabolism revealed through a nutrigenomic study. Hepatology. 2007;45:767–777. doi: 10.1002/hep.21510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]