Abstract

Serotonin (5-HT) is an intrinsic modulator of neural network excitation states in gastropod molluscs. 5-HT and related indole metabolites were measured in single, well-characterized serotonergic neurons of the feeding motor network of the predatory sea-slug Pleurobranchaea californica. Indole amounts were compared between paired hungry and satiated animals. Levels of 5-HT and its metabolite 5-HT-SO4 in the metacerebral giant neurons were observed in amounts approximately four-fold and two-fold, respectively, below unfed partners 24 h after a satiating meal. Intracellular levels of 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid and of free tryptophan did not differ significantly with hunger state. These data demonstrate that neurotransmitter levels and their metabolites can vary in goal-directed neural networks in a manner that follows internal state.

Keywords: serotonin, serotonin sulfate, Pleurobranchaea, appetite

Goal-directed neural networks, like those that mediate appetites for nutrients, can be under the control of both positive and negative afferent signals from the periphery. Those feedback signals, such as from gut and nutrient depots, may act in complex ways to regulate satiety state, acting to bias motor outputs toward or away from feeding expression. Thus, in mammals, hormone and metabolic signals from the periphery are integrated in the brain to promote or restrain food intake (Geary 2004; Riediger et al. 2004). However, little is known how satiation affects neurotransmitter levels in the central neurons of feeding-related neural networks. Neurotransmitter metabolism might well vary as cause and/or effect of satiety mechanisms. Gastropod molluscs provide useful model systems in which the neural circuitry of feeding and its control are relatively well characterized at the level of identified neurons that modulate pattern and gate feeding behavior. In these animals, identified serotonergic neurons that modulate excitability of feeding network elements are highly accessible, facilitating measures of 5-HT as well as related metabolites.

Serotonin is a modulatory neurotransmitter of the feeding motor network of gastropods that stimulates general arousal state and readiness to feed (Kupfermann et al. 1979; Palovcik et al. 1982). A major source of 5-HT in the feeding motor network is a bilateral pair of giant serotonergic neurons of the cerebral ganglia, often called the metacerebral giant neurons (MCGs). The MCGs are evolutionarily conserved in most opisthobranch and pulmonate gastropods (Pentreath et al. 1982), where they supply extensive serotonergic innervation of the feeding motor network in the buccal and cerebral ganglia, muscles of the feeding apparatus, esophagus and perioral chemosensory areas (Pentreath et al. 1973; Weiss et al. 1978; McCrohan and Benjamin 1980a; Moroz et al. 1997; Sudlow et al. 1998).

Metacerebral giant neurons’ electrical activity modulates excitation state of the feeding network (Pentreath et al. 1973; Weinreich et al. 1973; Berry and Pentreath 1976; Gillette and Davis 1977; Granzow and Kater 1977; Kupfermann et al. 1979; McCrohan and Benjamin 1980b; Kupfermann and Weiss 1981, 1982; Rosen et al. 1989; Kobatake et al. 1992; Arshavsky et al. 1993; Yeoman et al. 1996; Straub and Benjamin 2001). In the predatory sea-slug Pleurobranchaea californica (and probably most other snails), the MCGs are the only serotonergic neurons that project to the buccal ganglion (Sudlow et al. 1998; Newcomb et al. 2006), and are thus the only neuronal source of 5-HT for the feeding motor network in the buccal ganglion.

We tested whether indole levels in these neurons might fluctuate with hunger state by measuring indoleamine content of single MCGs from hungry and satiated Pleurobranchaea. We found that satiation is accompanied by a marked decrease in intracellular concentrations of 5-HT and its catabolite serotonin sulfate (5-HT-SO4), but not of the 5-HT precursor tryptophan (Trp) or the catabolite 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA).

Methods

Wild caught Pleurobranchaea californica were maintained for one to several weeks without feeding in aquaria in artificial sea water at 13°C. Feeding thresholds of satiated animals largely recover during a week’s deprivation (Davis et al. 1974). The term ‘hunger’ is defined and used here in terms of ‘readiness to feed’, which is multiply influenced by satiation state, learning, hormonal state, and general health. We manipulated satiation state in these studies and measured readiness to feed as chemosensory thresholds for proboscis extension and biting. Sixteen subjects were matched in pairs for size and thresholds and separated into experimental (satiated) and control groups. Feeding thresholds were measured as previous (Davis et al. 1974; Gillette et al. 2000), by recording those dilutions of betaine (trimethylglycine) at which proboscis extension and biting responses were observed during application to the oral veil of 1.5 mL volumes in ascending 10-fold concentrations from 10−6 to 10−1 mol/L over 10 s with a pasteur pipette. Betaine is the single most potent feeding stimulant (Gillette et al. 2000), and an abundant osmolyte of Pleurobranchaea’s invertebrate prey. Animal sizes determined by sea-water displacement ranged 80–500 mL. Experimental animals were fed with squid flesh until rejection occurred (usually 10–50% of body weight).

The day following satiation, cerebropleural ganglia were dissected out under cold anesthesia (2–4°C, at which animals become torpid), and somata of the MCGs of the feeding motor network identified visually by their position and large size were isolated by hand dissection. MCG somata were taken from each animal for analysis and measures were averaged for each pair when possible. In eight cases, one of the pair was damaged during the isolation: five from satiated and three from hungry animals. Thus, measures were obtained from 24 individual isolated somata. Of the complete cell pairs, 5-HT measures among pair members were significantly more similar to each other than to the whole population (correlation coefficient = 0.932; p = 0.0034, one-tailed). Isolated soma volumes were estimated as spheres from their diameters measured with an ocular micrometer of a dissecting microscope. Individual somata were transferred to a small amount of pH 8.7 borate buffer solution in 360 nL stainless steel vials and rapidly frozen with dry ice for subsequent analysis within 4 h. The buffer was prepared with 3.0 g boric acid (H3BO3; Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA or Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 9.2 g sodium borate (Na2B4O7·10 H2O; Fisher Scientific or Sigma) dissolved in 1 L ultrapure Millipore water (Milli-Q filtration system; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Immediately prior to analysis, the same buffer was delivered through a capillary syringe connected into the nanovial until a flat solution top was observed under microscope for a total sample volume of ca. 360 nL.

The analysis of indoles was performed by capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced wavelength-resolved fluorescence detection (CE-LIF), a technique developed for precise quantitation of the indoles in individual neurons (Fuller et al. 1998; Park et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 2001; Stuart et al. 2003, 2004). This system allows sensitive detection and spectral identification of species that naturally fluoresce with 257 nm excitation, including tyrosine, Trp, serotonin, and dopamine. Briefly, the detection end of a fused-silica capillary 800-mm long, 50 μm-inner diameter/140 μm-outer diameter (Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ, USA) was directed into a sheath flow assembly, where the core stream was excited by a frequency-doubled, liquid-cooled argon ion laser (Innova 300 FrED; Coherent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) operating at 257 nm. Both sheath flow and running buffer were pH 8.7 borate buffers. The sheath flow rate was about 0.5 mm/s. Laser power was 0.5 mW at the sheath flow cell. Collection optics were orthogonal to the excitation beam, focusing fluorescence emission to a f/2.2 CP 140 imaging spectrograph (Instruments SA, Edison, NJ, USA) and then onto a 1024 × 256 detector array, liquid-nitrogen-cooled scientific charge coupled device (EEV 15-11; Essex, UK). Sample injection was performed electrokinetically at 2.1 kV (current ca. 2.4 μA) for 10 s from a 360 nL stainless steel micro vial, and about 3 nL sample was injected into the capillary. The separation voltage was maintained at 21 kV (current ca. 25 μA). All experiments were performed at 22°C. The capillary was rinsed daily with 0.1 mol/L NaOH, water and running buffer (pH 8.7), 5 min each. Between runs the capillary was rinsed for 5 min with the running buffer. Fluorescence emission from 260 to 710 nm was processed and viewed in MATLAB (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) on a PC.

Standard calibration curves for each analyte, except 5-HT-SO4 (which was not available at the time of these measures) were generated on each day of sample analysis, both before and after samples are run, as previously described (Fuller et al. 1998). Three mixtures of standards (including 5-HT, Trp and 5-HIAA) were prepared in physiological saline (1 mL total volume for each mixture) in a concentration range of approximately 0.1–30 μmol/L. Linear calibration curves (R2 > 0.98) were created for each compound, relating the known concentration of each compound to the total signal count from the fluorescence detector. The limit of detection for 5-HT is 7–10 amol. CE-LIF analyses were carried out blindly, where the control and experimental identities were unknown to the individuals acquiring and analyzing single cell measures.

Results

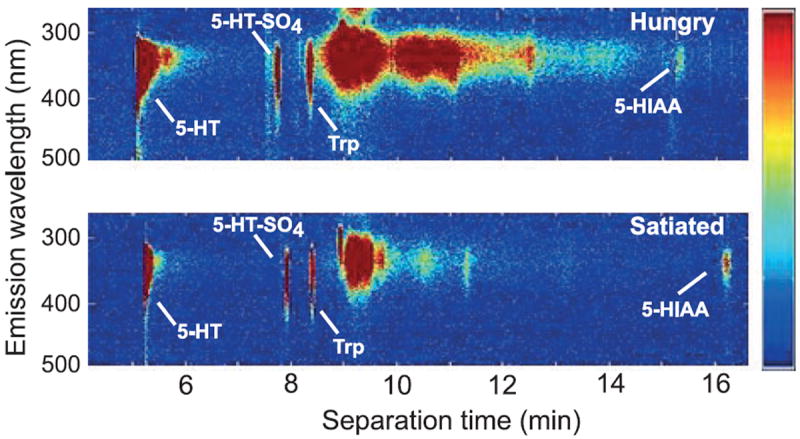

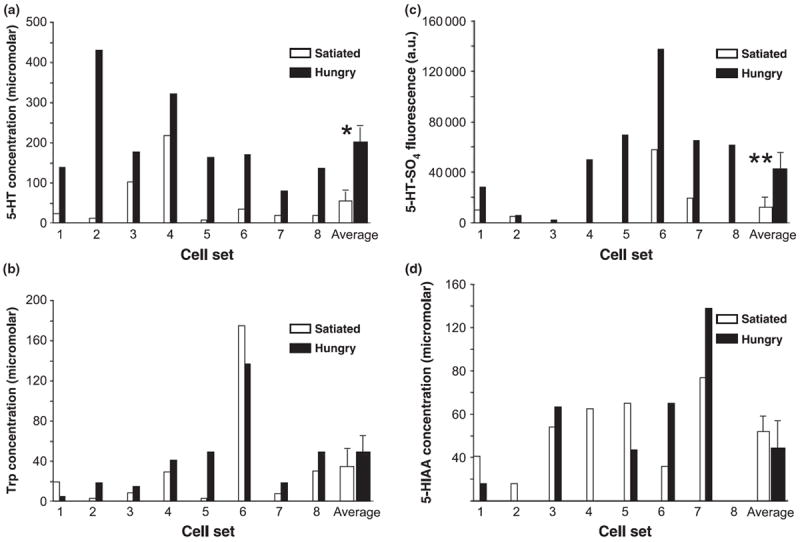

Paired wavelength-resolved electropherograms of MCG neurons from hungry animals and their satiated partners exhibited striking differences in both 5-HT and 5-HT-SO4 amounts (Fig. 1). Quantified results are shown for 5-HT, its precursor Trp, 5-HT-SO4 and 5-HIAA in Fig. 2. For each of the pair sets, 5-HT levels were higher in MCGs of hungry partners compared with satiated partners (Fig. 2a). 5-HT concentrations in MCGs of hungry animals averaged nearly four-fold greater than those of satiated animals (202 ± 25.8 μmol/L SEM vs. 54.3 ± 40.6 μmol/L); p < 0.008, two-tailed paired t-test). In contrast, values for MCG Trp levels showed no relationship to the hunger status (p > 0.4, two-tailed paired t-test; Fig. 2b).

Fig. 1.

Single cell wavelength-resolved fluorescence capillary electropherograms from metacerebral giant neurons of paired hungry (upper) and satiated animals (lower). Besides the identifiable compounds 5-HT, 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA), serotonin sulfate and tryptophan (Trp), a broad band of fluorescence emission represents Trp- and Tyrosine-containing proteins with an intensity that varied from animal to animal but did not significantly correlate with hunger state. Slight differences in analyte position (e.g., 5-HIAA) between electropherograms result from small differences in flow rate between runs. The color scale shows relative intensity of fluorescence emission (scale bar on right).

Fig. 2.

Histograms of (a) serotonin (5-HT), (b) tryptophan (Trp), (c) serotonin sulfate (5-HT-SO4), and (d) 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5- HIAA) levels from metacerebral giant neurons of hungry and satiated animal pairs. 5-HT-SO4 levels are presented as fluorescence intensities (arbitrary units). Hungry animals had significantly higher levels of 5-HT and 5-HT-SO4 than their satiated partners, while neither 5-HIAA nor Trp tracked hunger status. *p < 0.008, two-tailed paired t-test; **p = 0.003, two-tailed paired t-test.

It was of appreciable interest to discover in post hoc analyses of the electropherograms that the signal originating from 5-HT-SO4 was also significantly more intense in hungry than satiated animals (Fig. 2c). At the time the measurements were initiated, the 5-HT-SO4 peak had not yet been identified and so calibrations had not been made using 5-HT-SO4 standards. Thus, fluorescence intensity, rather than concentration is shown. Using fluorescence intensity, cells of hungry animals showed an average 173% higher value for 5-HT-SO4 (p = 0.003, two-tailed paired t-test). The range of variation of 5-HT-SO4 values was quite large; nearly 35-fold for lowest to highest values of cells of hungry animals. As calibration curves for 5-HT-SO4 run in subsequent experiments were unremarkably linear (Stuart et al. 2004), this appears to be natural variation among animal donors and might perhaps reflect both higher and more variable 5-HT turnover rates in more active cells of hungry donors. Finally, there was also no significant difference in 5-HIAA levels as a function of hunger status (Fig. 2d; p > 0.3, two-tailed paired t-test).

Discussion

These results provide evidence for regulation of neurotransmitter levels in functionally relevant and identified neurons by behavioral state. Satiating hungry Pleurobranchaea markedly reduced the 5-HT content of important modulatory neurons of the feeding motor network, the MCGs. The simple observations raise significant questions concerning the relation of behavioral state to cellular neurotransmitter metabolism and function. How are 5-HT and 5-HT-SO4 regulated, and what are the consequences?

Serotonin levels might be regulated by metabotropic effects of pathways mediating satiation (e.g., Jing et al. 2007). Alternatively, there is an interesting possibility that there is a function of electrical activity of serotonergic cells, which is known to be lower in the less active feeding motor networks of satiated Aplysia (Kupfermann and Weiss 1982), and probably Pleurobranchaea as well. Indeed, Meulemans et al. (1987), using intracellular voltammetry in the MCG homologs of Aplysia, measured rapid increases in a signal in the voltage range for 5-HT oxidation following depolarization. While the methods used did not distinguish between 5-HT, its metabolites, or changes in bound vesicular 5-HT, the observations indicate that one or more of these pools is highly sensitive to electrical activity. Satiation in Pleurobranchaea and other gastropods arises primarily from bulk stretch of the gut (Susswein and Kupfermann 1975; Croll et al. 1987; Elliot and Benjamin 1989), via inputs that reconfigure the feeding motor network for inhibition of feeding command neurons (Davis et al. 1983), thereby reducing excitation state in the feeding network (London and Gillette 1986) and raising feeding thresholds. Thus, as the MCG is part of the feeding network, state-dependent change in 5-HT levels could be a function of the firing activity of the neuron itself.

Evidence exists for 5-HT release as a function of pre-synaptic content in molluscan neurons (Fickbohm and Katz 2000; Marinesco and Carew, 2002; Marinesco et al. 2004), providing a potential mechanism for synaptic plasticity. Thus potentially, reduced 5-HT levels in MCGs of satiated animals would diminish 5-HT-dependent excitation of the feeding motor network by reducing spike-dependent release. The soma measures of 5-HT reported here are likely to be comparable to neuritic levels, both from diffusion and the high rates of orthograde transport of vesicular 5-HT reported in Aplysia (Goldberg et al. 1976). Moreover, 5-HT can be released from the molluscan neuron soma during stimulation (Miao et al. 2003). Future investigation may probe the relation of soma 5-HT measures to excitation/secretion efficacy.

The role of 5-HT-SO4 also remains for future investigation. Coincidence of its rise with 5-HT suggests increased 5-HT turnover in hungry animals. Previous CE-LIF measures found that 5-HT-SO4 is produced from 5-HT through sulfotransferase activity in neuropil, cell somas, and ganglion sheath, and that hemolymph 5-HT-SO4 oscillates in concentration with the diurnal activity rhythm of Pleurobranchaea (Stuart et al. 2003, 2004). In the previous report, 5-HT itself was undetectable in the hemolymph. The correlations of 5-HT-SO4 with changing 5-HT concentrations observed here raise the question of why 5-HT-SO4, but not the metabolite 5-HIAA, tracks internal state. Moreover, unlike 5-HT, 5-HT-SO4 has yet to demonstrate any electrogenic actions itself (Stuart et al. 2003), but might still be a factor in the regulation of 5-HT synthesis or breakdown, or could still play another distinct role. 5-HT-SO4 has been only recently identified as a 5-HT metabolite in molluscs (Stuart et al. 2003), and it is yet too early to dismiss it as a breakdown product with little physiological significance. The cost of its synthesis from 5-HT is two ATP molecules, assuming the arylsulfotransferase involved is similar to those previously characterized, and so requires similar co-factors including 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (Lansdon et al. 2004). Justification of this energetic expense cannot yet be determined beyond its probable usefulness as an indicator of general arousal state.

The associations and consequences of changing content of specific neurotransmitters with behavioral expression ask further elucidation at the level of the single neuron. Our results recall the inquiries of Lent et al. 1989, who showed that hungry leeches expressed higher levels of appetitive search, responsiveness to vibration, swimming, and feeding behaviors, all of which were 5-HT sensitive and coincided with higher levels of 5-HT in the CNS (Lent et al. 1989). Moreover, in desert locusts 11 of 13 neurotransmitters, including 5-HT, varied substantially between solitary and gregarious adult phases (Rogers et al. 2004), possibly because of changing neuronal concentrations. It remains for future investigations to determine whether content of 5-HT and other neurotransmitter molecules might vary state-dependently in the neurons of goal-directed neural networks in other invertebrates and vertebrates, as they do in Pleurobranchaea.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants MH59339, NS31609, IOB 04-47358 and DA018310A. We thank the director, Dennis Willows, and staff of the Friday Harbor Laboratories of the University of Washington where this work was initiated for their hospitality.

Abbreviations used

- 5-HIAA

5-hydroxyindole acetic acid

- 5-HT

serotonin

- 5-HT-SO4

serotonin sulfate

- CE-LIF

capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced wavelength-resolved fluorescence detection

- MCGs

metacerebral giant neurons

- Trp

tryptophan

References

- Arshavsky YI, Deliagina TG, Gamkrelidze GN, Orlovsky GN, Panchin YV, Popova LB, Shupliakov OV. Pharmacologically induced elements of the hunting and feeding behavior in the pteropod mollusk Clione limacina. I. Effects of GABA. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:512–521. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.2.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MS, Pentreath VW. Properties of a symmetric pair of serotonin-containing neurones in the cerebral ganglia of Planorbis. J Exp Biol. 1976;65:361–380. doi: 10.1242/jeb.65.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll RP, Albuquerque T, Fitzpatrick L. Hyperphagia resulting from gut denervation in the sea slug Pleurobranchaea. Behav Neural Biol. 1987;47:212–218. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(87)90341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis WJ, Mpitsos GJ, Pinneo JM. The behavioral hierarchy of Pleurobranchaea. I. The dominant position of the feeding behavior. J Comp Physiol. 1974;90:207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Davis WJ, Gillette R, Kovac MP, Croll RP, Matera E. Organization of synaptic inputs to paracerebral feeding command interneurons of Pleurobranchaea californica III. Modifications induced by experience. J Neurophysiol. 1983;49:1557–1572. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.49.6.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot CJH, Benjamin PR. Esophageal mechanoreceptors in the feeding system of the pond snail, Lymnaea stagnalis. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:727–736. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickbohm DJ, Katz PS. Paradoxical actions of the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan on the activity of identified serotonergic neurons in a simple motor circuit. J Neurosci. 2000;15:1622–1634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01622.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RR, Moroz LL, Gillette R, Sweedler JV. Single neuron analysis by capillary electrophoresis with fluorescence spectroscopy. Neuron. 1998;20:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary N. Endocrine controls of eating: CCK, leptin, and ghrelin. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:719–733. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette R, Davis WJ. The role of the metacerebral giant neuron in the feeding behavior of Pleurobranchaea. J Comp Physiol. 1977;116:129–159. [Google Scholar]

- Gillette R, Huang R-C, Hatcher N, Moroz LL. Cost-benefit analysis potential in feeding behavior of a predatory snail by integration of hunger, taste and pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3585–3590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DJ, Goldman JE, Schwartz JH. Alterations in amounts and rates of serotonin transported in an axon of the giant cerebral neurone of Aplysia californica. J Physiol (Lond) 1976;259:473–490. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granzow B, Kater SB. Identified higher-order neurons controlling the feeding motor program of Helisoma. Neuroscience. 1977;2:1049–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Jing J, Vilim FS, Horn CC, et al. From hunger to satiety: reconfiguration of a feeding network by Aplysia neuropeptide Y. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3490–3502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0334-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobatake E, Kawahara S, Yano M, Shimizu H. Control of feeding rhythm in the terrestrial slug Incilaria bilineata. Neurosci Res. 1992;13:257–265. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(92)90038-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfermann I, Weiss KR. The role of serotonin in arousal of feeding behavior of Aplysia. In: Jacobs B, Gelperin A, editors. Serotonin Neurotransmission and Behavior. Cambridge MIT Press; Cambridge: 1981. pp. 255–287. [Google Scholar]

- Kupfermann I, Weiss KR. Activity of an identified serotonergic neuron in free moving Aplysia correlates with behavioral arousal. Brain Res. 1982;241:334–337. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfermann I, Cohen JL, Mandelbaum DE, Schonberg M, Susswein AJ, Weiss KR. Functional role of serotonergic neuromodulation in Aplysia. Fed Proc. 1979;38:2095–2102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdon EB, Fisher AJ, Segel IH. Human 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthetase (isoform 1, brain): kinetic properties of the adenosine triphosphate sulfurylase and adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate kinase domains. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4356–4365. doi: 10.1021/bi049827m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lent CM, Dickinson MH, Marshall CG. Serotonin and leech feeding behavior: obligatory neuromodulation. Am Zool. 1989;29:1241–1254. [Google Scholar]

- London JA, Gillette R. Mechanism for food avoidance learning in the central pattern generator of feeding behavior of Pleurobranchaea californica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4058–4062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinesco S, Carew TJ. Serotonin release evoked by tail nerve stimulation in the CNS of Aplysia: Characterization and relationship to heterosynaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2299–2312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02299.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinesco S, Wickremasinghe N, Kolkman KE, Carew TJ. Serotonergic modulation in Aplysia. II. Cellular and behavioral consequences of increased serotonergic tone. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2487–2496. doi: 10.1152/jn.00210.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrohan CR, Benjamin PR. Patterns of activity and axonal projections of the cerebral giant cells of the snail Lymnaea stagnalis. J Exp Biol. 1980a;85:149–168. doi: 10.1242/jeb.85.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrohan CR, Benjamin PR. Synaptic relationships of the cerebral giant cells with motoneurones in the feeding system of Lymnaea stagnalis. J Exp Biol. 1980b;85:169–186. doi: 10.1242/jeb.85.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulemans A, Poulain B, Baux G, Tauc L. Changes in serotonin concentration in a living neurone: a study by on-line intracellular voltammetry. Brain Res. 1987;414:158–162. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Analysis of serotonin release from single neuron soma using capillary electrophoresis and laser-induced fluorescence with a pulsed deep-UV NeCu laser. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;377:1007–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz LL, Sudlow LC, Jing J, Gillette R. Serotonin-immunoreactivity in peripheral tissues of the opisthobranch molluscs Pleurobranchaea californica and Tritonia diomedea. J Comp Neurol. 1997;382:176–188. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970602)382:2<176::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb JM, Fickbohm CK, Katz PS. Comparative mapping of serotonin-immunoreactive neurons in the central nervous systems of nudibranch molluscs. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:485–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.21111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palovcik RR, Basberg BA, Ram JL. Behavioral state changes induced in Pleurobranchaea and Aplysia by serotonin. Behav Neural Biol. 1982;35:383–394. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(82)91034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YH, Zhang X, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Independent optimization of capillary electrophoresis separation and native fluorescence detection conditions for indolamine and cate-cholamine measurement. Anal Chem. 1999;71:4997–5002. doi: 10.1021/ac990659r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentreath VW, Osborne NN, Cottrell GA. Anatomy of giant serotonin-containing neurones in the cerebral ganglia of Helix pomatia and Limax maximus. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1973;143:1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00307447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentreath VW, Berry MS, Osborne NN. The serotonergic cerebral cells in gastropods. In: Osborne NN, editor. Biology of Serotonergic Transmission. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 1982. pp. 457–513. [Google Scholar]

- Riediger T, Bothe C, Becskei C, Lutz TA. Peptide YY directly inhibits ghrelin-activated neurons of the arcuate nucleus and reverses fasting-induced c-Fos expression. Neuroendocrinol. 2004;79:317–326. doi: 10.1159/000079842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SM, Matheson T, Sasaki K, Kendrick K, Simpson SJ, Burrows M. Substantial changes in central nervous system neurotransmitters and neuromodulators accompany phase change in the locust. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3603–3617. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen SC, Weiss KR, Goldstein RS, Kupfermann I. The role of a modulatory neuron in feeding and satiation in Aplysia: effects of lesioning of the serotonergic metacerebral cells. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1562–1578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01562.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub VA, Benjamin PR. Extrinsic modulation and motor pattern generation in a feeding network: a cellular study. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1767–1778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01767.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart JN, Zhang X, Jakubowski JA, Romanova EV, Sweedler JV. Serotonin catabolism depends upon location of release: characterization of sulfated and γ-glutamylated serotonin metabolites in Aplysia californica. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1358–1366. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart JN, Ebaugh JD, Copes AL, Hatcher N, Gillette R, Sweedler JV. Systemic serotonin sulfate in marine mollusks. J Neurochem. 2004;90:734–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudlow LC, Jing J, Moroz L, Gillette R. Serotonin immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the marine molluscs Pleurobranchaea californica and Tritonia diomedea. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:466–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susswein AJ, Kupfermann I. Bulk as a stimulus for satiation in Aplysia. Behav Biol. 1975;13:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(75)91903-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich D, McCaman MW, McCaman RE, Vaughn JE. Chemical, enzymatic, and ultrastructural characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine-containing neurons from the ganglia of Aplysia californica and Tritonia diomedia. J Neurochem. 1973;20:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss KR, Cohen JL, Kupfermann I. Modulatory control of buccal musculature by a serotonergic neuron (metacerebral cell) in Aplysia. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:181–203. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoman MS, Brierley MJ, Benjamin PR. Central pattern generator interneurons are targets for the modulatory serotonergic cerebral giant cells in the feeding system of Lymnaea. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:11–25. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Fuller RR, Dahlgren RL, Potgieter K, Gillette R, Sweedler JV. Neurotransmitter sampling and storage for capillary electrophoresis analysis. Fresenius’ J Anal Chem. 2001;369:206–211. doi: 10.1007/s002160000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]