Abstract

Background:

Epidural opioids acting through the spinal cord receptors improve the quality and duration of analgesia along with dose-sparing effect with the local anesthetics. The present study compared the efficacy and safety profile of epidurally administered butorphanol and fentanyl combined with bupivacaine (B).

Materials and Methods:

A total of 75 adult patients of either sex of American Society of Anesthesiologist physical status I and II, aged 20-60 years, undergoing lower abdominal under epidural anesthesia were enrolled into the study. Patients were randomly divided into three groups of 25 each: B, bupivacaine and butorphanol (BB) and bupivacaine + fentanyl (BF). B (0.5%) 20 ml was administered epidurally in all the three groups with the addition of 1 mg butorphanol in BB group and 100 μg fentanyl in the BF group. The hemodynamic parameters as well as various block characteristics including onset, completion, level and duration of sensory analgesia as well as onset, completion and regression of motor block were observed and compared. Adverse events and post-operative visual analgesia scale scores were also noted and compared. Data was analyzed using ANOVA with post-hoc significance, Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. Value of P < 0.05 was considered significant and P < 0.001 as highly significant.

Results:

The demographic profile of patients was comparable in all the three groups. Onset and completion of sensory analgesia was earliest in BF group, followed by BB and B group. The duration of analgesia was significantly prolonged in BB group followed by BF as compared with group B. Addition of butorphanol and fentanyl to B had no effect on the time of onset, completion and regression of motor block. No serious cardio-respiratory side effects were observed in any group.

Conclusions:

Butorphanol and fentanyl as epidural adjuvants are equally safe and provide comparable stable hemodynamics, early onset and establishment of sensory anesthesia. Butorphanol provides a significantly prolonged post-operative analgesia.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, butorphanol, epidural anesthesia, fentanyl, lower abdominal surgery

INTRODUCTION

Narcotic analgesics are commonly used as adjuncts to local anesthetics (LA) in epidural anesthesia. They hasten the onset, improve the quality of the block as well as prolong the duration of analgesia. However, the parent drug (morphine) that was initially employed for epidural analgesia had low lipid solubility and a long latency. Its use has been associated with the occurrence of undesirable side effects as pruritus, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention and respiratory depression.[1] The search for a better molecule is still going on. Butorphanol is a lipid-soluble narcotic with weak μ-receptor agonist and antagonist activity and strong k-receptor agonism.[2] It has strong analgesic and sedative properties without respiratory depression. Butorphanol has been frequently used for post-operative analgesia and labor analgesia.[3,4] Fentanyl is a highly lipid-soluble, strong μ-receptor agonist and phenyl piperidine derivative with a rapid onset and short duration of action.[5] Previous studies have compared the two narcotics for post-operative epidural analgesia.[6,7,8] None of studies have compared fentanyl and butorphanol as adjuncts for intraoperative epidural anesthesia. The present study was undertaken to compare the safety and efficacy of epidural butorphanol versus epidural fentanyl for lower abdominal surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institute's Ethical Committee approval and informed consent from the patients, 75 adult patients of either sex of American Society of Anesthesiologist grade I or II in the age group of 20-60 years, undergoing lower abdominal and lower limb surgery under epidural anesthesia were enrolled into the study. Exclusion criteria included patient's refusal, spinal deformity, bleeding diathesis, sepsis, significant cardiorespiratory and hepatic, renal and neurological disease. Patients were familiarized with visual analgesia scale (VAS) scoring pre-operatively and taught to grade their pain on the scale.

Ranitidine 150 mg and alprazolam 0.25 mg orally were given as premedicants 2 h before the surgery. In the operating room, the patient was connected to a multichannel monitor showing electrocardiography, heart rate (HR), non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry (SpO2) and respiratory rate (RR). A peripheral venous access with 18G cannula was secured. The patients were pre-loaded with Ringer's lactate 10 ml/kg over 15-20 min prior to epidural block. With proper positioning and under all aseptic precautions epidural space was identified in L3-4 intervertebral space using 18G Tuohy's needle with the loss of resistance to air technique. Epidural catheter was threaded 3-4 cm inside the epidural space and fixed.

A test dose of 3 ml of 1.5% lignocaine with adrenaline was given after initial negative aspiration for blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Then, 20 ml of 0.5% plain bupivacaine (B) alone or along with one of the two study drugs was injected into the epidural space. Patients were randomly divided by computer generated random numbers into three groups of 25 each: B, bupivacaine and butorphanol (BB) and bupivacaine + fentanyl (BF). B (0.5%) 20 ml was administered epidurally in all the three groups with the addition of 1 mg butorphanol in BB group and 100 μg fentanyl in the BF group. The study drugs were prepared by a trained anesthesia technician and the anesthesiologist giving the epidural block and making the observations in the intra-operative as well as the post-operative period was unaware of the drug used. The hemodynamic parameters including HR, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), RR and SpO2 were monitored and noted every 5 min for the first 20 min and then every 10 min until the end of surgery. The various block characteristics were observed including:

Onset of analgesia: It was taken as the time from injection of LA solution up to feeling of warmth or loss of pin — prick sensation in any dermatome.

Completion of analgesia: It was taken as the time from initial onset of analgesia up to the time when analgesia attained its maximum dermatomal level, with no further rise for 5 min.

Level of analgesia: It was assessed in the midline from symphysis pubis going upward and the highest dermatome showing analgesia was taken as level of analgesia.

-

Quality of analgesia: It was graded as follows:

Good — When there was no complaint of pain or discomfort during the procedure.

Fair — When pain or discomfort was felt only during specific stage of procedure, like traction on viscera/peritoneum.

Poor — When the patient complained of pain during the surgery and needed top up with epidural LA.

Onset of motor block: Time from the injection of LA solution up to the time when the patient felt the heaviness in the lower limbs.

Completion of motor block: Time between the initial onset of motor block until the time when the patient was unable to move his or her toes or raise lower limbs.

Regression of motor block: Time when the patient was unable to move his or her toes or lower limbs until the time when the patient started moving his or her toes or lower limbs.

Sensory block was assessed by pin-prick method using a blunt needle at 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30 and 60 min post-drug injection into the epidural space. The motor block was measured at 0, 10, 20 and 30 min post-drug administration and every 30 min post-surgery until the regression of the motor block. The surgical procedure was started 30 min after the drug injection.

In the post-operative period, pain scores were assessed on the VAS scale every hour till 6 h and then every 2 h till 24 h. Vitals were recorded at the same time intervals as pain scores. Duration of analgesia was taken as the time from the onset of analgesia up to the time when the VAS reached 5. Patient was then given the rescue analgesic (Tramadol 100 mg in 10 ml normal saline) through the epidural catheter and study in that patient ceased. The epidural catheter was kept for 24 h in the post-operative period and post-operative analgesia was maintained with epidural top ups with Tramadol 100 mg in 10 ml normal saline on patient demand. Complications such as, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, headache, pruritus, respiratory depression was noted and treated accordingly.

Statistical analysis

The data collected was subjected to statistical analysis using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 13). During the planning stage of the study, the sample size was calculated with the help of power analysis. Assuming type I error of 0.05 and a type II error of 0.1 to detect 30 min difference in post-operative analgesia so as to yield a power of 80%, a sample size of 21 patients was calculated for each group. The inclusion of 25 patients in each group was done for better validation of results. Data is expressed as mean with a standard deviation. Discrete data is expressed as frequency with percentage of total. Normal distribution was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using ANOVA with post hoc analysis using Bonferroni test. Chi-square test and Fischer exact test were used to compare discrete variables between the groups. A P < 0.05 was considered as a significant difference and P < 0.0001 as highly significant.

RESULTS

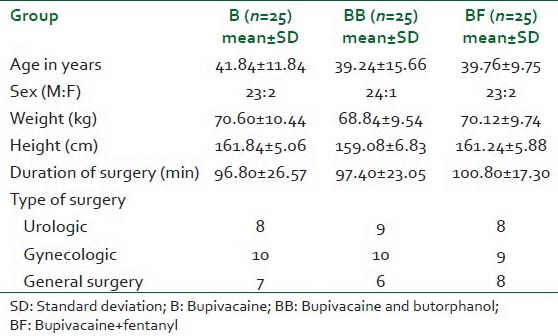

The three groups were comparable with regard to age, weight, height and gender distribution of the patients, duration and type of the surgery [Table 1]. Pre-operative HR, SBP, DBP, MAP, RR and SpO2 were also comparable in the groups. There was no statistically significant change in the hemodynamic parameters in any group throughout the study period.

Table 1.

Demographic data

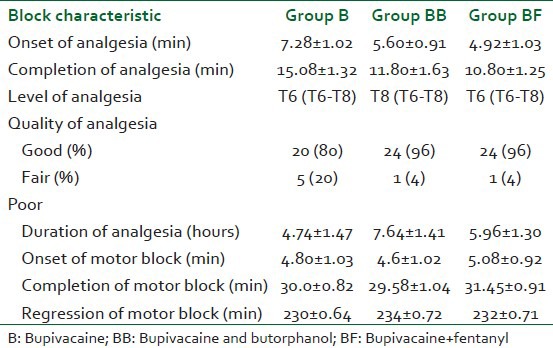

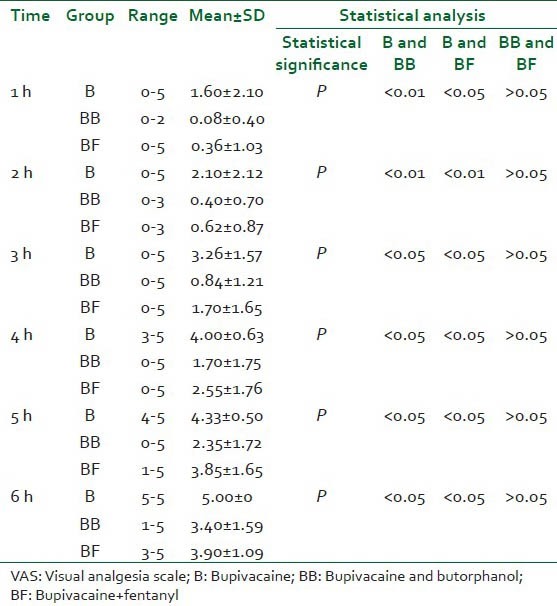

The onset and completion of analgesia was hastened with the addition of both butorphanol and fentanyl. There was a statistically significant difference in the onset and completion of analgesia between group B and group BB and group B and BF (P < 0.05) [Table 2]. However, this difference was not significant between group BB and group BF. Level of analgesia was comparable in all the three groups (P > 0.05). The addition of opioids improved the quality of the block as well. The difference in the quality of analgesia was statistically significant between group B and BB and group B and BF (P < 0.05) and non-significant between group BB and BF (P > 0.05) [Table 2]. There was no case of epidural failure and no patient required epidural top-up with LA in the intraoperative period. The mean time of onset, completion and regression of motor block was comparable in all the three groups. The pain scores were significantly less in group BB and BF as compared to group B while there was no difference in the VAS scores between group BB and BF (P > 0.05) throughout the study period [Table 3]. The duration of sensory analgesia was prolonged with the addition of butorphanol and fentanyl. The difference in the duration of analgesia in all the three groups was found to be statistically highly significant. Sedation scores were higher in group BB as compared with group BF and group B. Mean value of OAA/S was 4.90 ± 0.54, 4.00 ± 0.60 and 4.70 ± 0.64 in group B, group BB and group BF. The difference in the OAA/S score was statistically significant between group B and BB as well as between group BB and group BF (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

The block characteristics in all the three groups

Table 3.

The mean post-operative pain scores (VAS) at different time interval in all the three groups

Few minor side effects were observed during the study period. The incidence of nausea and vomiting was 8% in group B, 4% in group BB and 12% in group BF. Pruritus was observed in 25% cases in group BF as compared with 2% in group BB. Respiratory depression was not observed in any patient. No patient had urinary retention.

DISCUSSION

Opioids as epidural adjuvants to LA improve the quality of the block and provide a dose-sparing effect.[10,11] We chose to investigate fentanyl, a μ-receptor agonist and butorphanol, a strong k-receptor agonist and a weak μ-receptor agonist-antagonist administered epidurally along with B for intra-operative and post-operative analgesia.

Our results demonstrate that the addition of fentanyl and butorphanol to B quickens the onset as well as completion of analgesia. Administration of 20 ml of 0.5% plain B showed latency of 6-11 min (mean 7.28) and the analgesia was completed in 12-18 min (mean 15.08), consistent with the study by Moore et al.[12] Addition of 1 mg butorphanol to 20 ml 0.5% plain B reduced the latency of onset of analgesia to 5-9 min and the completion of analgesia occurred earlier (9-14 min; mean 11.80). Abboud et al.[13] studied epidural butorphanol for the relief of post-operative pain after caesarean section and reported the time of onset of pain relief with 1 mg butorphanol to be 15 min. Mok et al.[14] compared epidural butorphanol and morphine for the relief of post-operative pain and reported the onset of pain relief at 15 min with 4 mg butorphanol and peak pain relief at 30 min. the difference observed is probably due to the fact that the authors had used butorphanol dissolved in normal saline in the post-operative period, when the patient complained of moderate to severe pain and while in our study, 1 mg butorphanol was administered along with 20 ml 0.5% plain B before the start of surgery. The onset of analgesia was more rapid (4-8 min; mean 4.92) and was completed in 8-13 min (mean 10.80) with the addition of 100 μg fentanyl to 20 ml 0.5% plain B. Cousins and Mather[15] reported the time of onset of analgesia with epidural fentanyl 100 μg to be 4-10 min.

The quality of the sensory block was significantly improved with the addition of both the opioids to B. Majority of the patients in group BB and group BF had good quality of analgesia. No patient received any supplemental analgesic during the surgery.

The pain scores as assessed on the VAS were low and remained low for a significant time in the post-operative period with the addition of fentanyl or butorphanol to B [Table 3]. The duration of analgesia was also significantly prolonged with the addition of narcotics to LA. We observed duration of analgesia with 20 ml 0.5% B alone to be 2-7 h (mean 4.76) in consistent with other studies that given by Modig and Paalzov[16] (range 2.7-5 h; mean 4.3) and Paech et al.[17] (mean 5.2 h). The duration of analgesia was prolonged with the addition of 100 μg fentanyl (3-9 h; mean 5.96) in our study, consistent with that given by Cousins and Mather[15] (5.7 h) and Paech et al.[17] (5.2 h). The duration of analgesia was longest with B-butorphanol combination (5-10 h; mean 7.64). Various studies using epidural butorphanol for post-operative analgesia have reported the duration of analgesia to be 4-6 h, 5 h and 5.35 h with 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg and respectively.[13,18,19] Malik et al.[7] have also reported in their study that butorphanol provides a longer duration of analgesia than fentanyl, similar to our study.

Narcotic analgesics are well-known for the potential side effects such as pruritus, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention and respiratory depression.[20] Delayed respiratory depression is the most troublesome of these side effects and appears to be largely responsible for the reluctance of anesthesiologists to use intrathecal or epidural narcotics. This phenomenon is thought to be due to transport of drug in cerebrospinal fluid from the lumbar region to the fourth ventricle, with consequent depression of the medullary respiratory centers. The incidence of delayed respiratory depression appears to be greatest with poorly lipid-soluble narcotic drugs, like morphine.[21] Bromage[1] suggested that lipid-soluble, highly protein bound narcotic analgesics might be less likely to exhibit this phenomenon and this appears to be true for both butorphanol and fentanyl. The patients were continuously observed for respiratory depression with SpO2 (< 90%) and RR (< 10). No case of respiratory depression was observed in any group, consistent with other studies.[6,7,22,23] The incidence of pruritus was higher in group BF (25%) as compared to group (BB). Previous studies have documented the incidence of pruritus with epidural fentanyl to be 23%, 41% and 46.7%.[7,22,24] Pruritus has been observed in few patients receiving epidural butorphanol in previous studies, 1.4% and 3%.[7,25] Three cases in group BF and one in group BB had nausea. Two patients in group BF had vomiting and were administered injection ondansetron 4 mg intravenously slowly. These observations are comparable with those reported by Abboud et al.[13] and Naulty et al.[22] No patient had urinary retention in either of the groups, consistent with the study by Ackerman et al. The side-effect observed in the majority of patients with butorphanol was somnolence as observed by other authors as well.[7,13,22,23] The sedation caused by epidural butorphanol is often desirable in the perioperative period.

CONCLUSION

Addition of the opioids, i.e., butorphanol and fentanyl significantly quickens the onset and completion of analgesia and provide more effective and longer duration of analgesia as compared with B alone. A single bolus dose of butorphanol and fentanyl along with B given at the start of epidural anesthesia provides good intraoperative and post-operative analgesia. The administration of these drugs in the epidural space is devoid of serious cardio-respiratory side effects.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Bromage PR. The price of intraspinal narcotic analgesics: Basic constraints (editorial) Anaesth Analg. 1989;68:323–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt CO, Naulty JS, Malinow AM, Datta S, Ostheimer GW. Epidural butorphanol-bupivacaine for analgesia during labor and delivery. Anesth Analg. 1989;68:323–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharti N, Chari P. Epidural butorphanol-bupivacaine analgesia for postoperative pain relief after abdominal hysterectomy. J Clin Anesth. 2009;21:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrestha CK, Sharma KR, Shrestha RR. Comparative study of epidural administration of 10 ml of 0.1% bupivacaine with 2 mg butorphanol and 10 ml of 0.25% plain bupivacaine for analgesia during labor. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2007;46:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore RA, Bullingham RE, McQuay HJ, Hand CW, Aspel JB, Allen MC, et al. Dural permeability to narcotics: In vitro determination and application to extradural administration. Br J Anaesth. 1982;54:1117–28. doi: 10.1093/bja/54.10.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujinaga M, Mazze RI, Baden JM, Fantel AG, Shepard TH. Rat whole embryo culture: An in vitro model for testing nitrous oxide teratogenicity. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:401–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik P, Manchanda C, Malhotra N. Comparative evaluation of epidural fentanyl and butorphanol for post-operative analgesia. J Anesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2006;22:377–82. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szabova A, Sadhasivam S, Wang Y, Nick TG, Goldschneider K. Comparison of postoperative analgesia with epidural butorphanol/bupivacaine versus fentanyl/bupivacaine following pediatric urological procedures. J Opioid Manag. 2010;6:401–7. doi: 10.5055/jom.2010.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chernik DA, Gillings D, Laine H, Hendler J, Silver JM, Davidson AB, et al. Validity and reliability of the Observer's Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale: Study with intravenous midazolam. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10:244–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Singh A, Bakshi G, Singh K, et al. Admixture of clonidine and fentanyl to ropivacaine in epidural anesthesia for lower abdominal surgery. Anesth Essays Res. 2010;4:9–14. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.69299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajwa SJ, Arora V, Kaur J, Singh A, Parmar SS. Comparative evaluation of dexmedetomidine and fentanyl for epidural analgesia in lower limb orthopedic surgeries. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:365–70. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.87264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore DC, Bridenbaugh LD, Thompson GE, Balfour RI, Horton WG. Bupivacaine: A review of 11,080 cases. Anesth Analg. 1978;57:42–53. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abboud TK, Moore M, Zhu J, Murakawa K, Minehart M, Longhitano M, et al. Epidural butorphanol for the relief of post-operative pain after caesarean section. Anaesthesiol. 1986;65:A397. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mok MS, Tsai YJ, Ho WM. Efficacy of epidural butorphanol compared to morphine for the relief of post-operative pain. Anaesthesiol. 1986;65:A175. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cousins MJ, Mather LE. Intrathecal and epidural administration of opioids. Anesthesiology. 1984;61:276–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modig J, Paalzow L. A comparison of epidural morphine and epidural bupivacaine for postoperative pain relief. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1981;25:437–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1981.tb01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paech MJ, Westmore MD, Speirs HM. A double-blind comparison of epidural bupivacaine and bupivacaine-fentanyl for caesarean section. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1990;18:22–30. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9001800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan PH, Chou AK, Perng JS, Chung HC, Lee CC, Mok MS. Comparison of epidural butorphanol plus clonidine with butorphanol alone for postoperative pain relief. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 1997;35:91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta R, Kaur S, Singh S, Aujla KS. A comparison of Epidural Butorphanol and Tramadol for Postoperative Analgesia Using CSEA Technique. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:35–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafsson LL, Schildt B, Jacobsen K. Adverse effects of extradural and intrathecal opiates: Report of a nationwide survey in Sweden. Br J Anaesth. 1982;54:479–86. doi: 10.1093/bja/54.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camporesi EM, Nielsen CH, Bromage PR, Durant PA. Ventilatory CO2 sensitivity after intravenous and epidural morphine in volunteers. Anesth Analg. 1983;62:633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naulty JS, Johnson M, Burger GA, Datta S, Weiss JR, Morrison J, et al. Epidural fentanyl for post cesarean delivery pain management. Anesthesiol. 1983;59:415. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198512000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palacios QT, Jones MM, Hawkins JL, Adenwala JN, Longmire S, Hess KR, et al. Post-caesarean section analgesia: A comparison of epidural butorphanol and morphine. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38:24–30. doi: 10.1007/BF03009159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackerman WE, Juneja MM, Kaczorowski DM, Colclough GW. A comparison of the incidence of pruritus following epidural opioid administration in the parturient. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36:388–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03005335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunter JB, McAuliffe J, Gregg T, Weidner N, Varughese AM, Sweeney DM. Continuous epidural butorphanol relieves pruritus associated with epidural morphine infusions in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2000;10:167–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2000.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]