Abstract

The pollen wall, an essential structure for pollen function, consists of two layers, an inner intine and an outer exine. The latter is further divided into sexine and nexine. Many genes involved in sexine development have been reported, in which the MYB transcription factor Male Sterile 188 (MS188) specifies sexine in Arabidopsis. However, nexine formation remains poorly understood. Here we report the knockout of TRANSPOSABLE ELEMENT SILENCING VIA AT-HOOK (TEK) leads to nexine absence in Arabidopsis. TEK encodes an AT-hook nuclear localized family protein highly expressed in tapetum during the tetrad stage. Absence of nexine in tek disrupts the deposition of intine without affecting sexine formation. We find that ABORTED MICROSPORES directly regulates the expression of TEK and MS188 in tapetum for the nexine and sexine formation, respectively. Our data show that a transcriptional cascade in the tapetum specifies the development of pollen wall.

The nexine is a conserved layer of the pollen wall in land plants. The authors show that the AHL family protein TRANSPOSABLE ELEMENT SILENCING VIA AT-HOOK (TEK) is necessary for nexine formation in Arabidopsis, acting downstream of the transcription factor ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS).

The nexine is a conserved layer of the pollen wall in land plants. The authors show that the AHL family protein TRANSPOSABLE ELEMENT SILENCING VIA AT-HOOK (TEK) is necessary for nexine formation in Arabidopsis, acting downstream of the transcription factor ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS).

The multilayered, structurally complex walls typical of angiosperm pollen grains exhibit a greater level of organizational complexity than those of any other cell type1. The main roles of the pollen wall are in guiding the male gametophyte development in anthers, protecting the pollen from various environmental stresses and functioning in cell–cell recognition during pollination1,2,3. The vast morphological diversity exhibited by pollen walls is the basis of the discipline of palynology and there is much interest in understanding how this diversity has arisen4. The pollen wall consists of a specialized outer exine, composed of sporopollenin, and an inner cellulosic intine. Sporopollenin is highly resistant to physical, chemical and biological degradation5,6. Based on cytological and molecular evidence, tapetum fills the role of sporopollenin biosynthesis for exine formation7,8,9,10,11,12. In angiosperms, the pollen exine is divided into sexine and nexine. The non-sculptured nexine is distinguished as a distinct layer between the sculptured sexine and an inner intine, which appears to be strongly conserved in seed plants13,14,15. However, apart from its morphological description, knowledge on the formation of the nexine and its function is rather meagre. Therefore, the recognition of nexine formation in pollen wall development not only provides insight into plant phylogeny but also reveals the gene-determined mechanisms that underlie the ontogeny of the major layers of the pollen wall.

Recently, well-characterized genes in which mutations cause male sterile phenotype have enriched our understanding of key events in pollen wall development. Most of them, which are highly expressed in the tapetum, are required for exine formation. In vitro enzyme activity analysis revealed that they synthesize polymers such as sporopollenin precursors16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The regulatory factors required for tapetum development and function are also important for the pollen wall formation11,12,23. Among them, five transcription factors form a genetic pathway (DYT1-TDF1-AMS-MS188-MS1) that regulates tapetum development and function24. In this pathway, DYSFUNCTIONAL TAPETUM1 (DYT1) encodes a bHLH transcription factor; DEFECTIVE in TAPETAL DEVELOPMENT and FUNCTION1 (TDF1) encodes a R2R3 MYB transcription factor, which both function in the early stages of tapetum development and are essential for the expression of tapetal genes25,26. ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS), an MYC class transcription factor, directly regulates the expression of ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter G26 (ABCG26, also named WBC27), which is a putative transporter of tetraketide sporopollenin precursors for exine formation12,27,28,29. MS188 encodes an R2R3 MYB transcription factor that specially affects sexine formation11.

Here we report the identification of an Arabidopsis mutant transposable element silencing via AT-hook (tek) that is associated with the formation of the nexine layer. The TEK encodes an AT-hook nuclear localized (AHL) protein and is highly expressed in the tapetal layer at tetrad stage. We show that AMS in the tapetum directly regulates TEK and MS188 for nexine and sexine layer formation, and that the presence of an intine layer depends on the formation of the nexine. These results establish a series of transcriptional events that eventually dictate the development of the different layers of the pollen wall.

Results

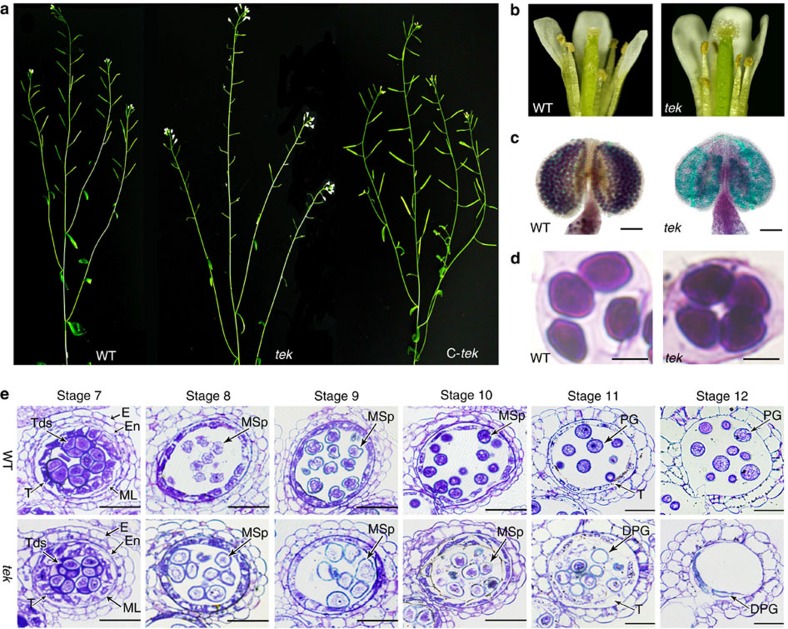

TEK knockout leads to male sterility

To identify genes essential for anther development, a sterile mutant was isolated in a collection of T-DNA-tagged lines30. The T-DNA is inserted in At2g42940 (see below), which was previously designated as TRANSPOSABLE ELEMENT SILENCING VIA AT-HOOK (TEK). Knockdown of TEK led to late flowering31. Here we focus on the mechanism of the male sterility of tek. The tek mutant was indistinguishable from wild type during vegetative growth, by its short siliques without seeds (Fig. 1a). No pollen was observed on the stamens and stigma of flowers (Fig. 1b) and Alexander’s staining showed that all pollen grains in the locule were aborted during the late stages of anther development (Fig. 1c). Each mutant tetrad contained four microspores that were similar to those of wild type, indicating that meiosis is normal in tek (Fig. 1d). Reciprocal crosses with wild type indicated that female fertility was not affected in the tek mutant. The fertile and sterile plants of F2 population segregated with 3:1 (281:95) ratio, indicating a single recessive sporophytic mutation for tek.

Figure 1. TEK knockout leads to the defective pollen development.

(a) The wild type (WT), tek plant with short siliques (tek) and complemented plant with normal siliques (C-tek). (b) The flower of wild type and tek. (c) Alexander’s staining of wild-type and tek anther. Scale bar, 100 μm. (d) The tetrad of wild type and tek. Scale bars, 10 um. (e) Sections of wild type and tek showing anther development from stage 7–12. DPG, degenerated pollen grain; E, epidermis; En, endothecium; ML, middle layer; MSp, microspore; PG, pollen grain; T, tapetum; Tds, tetrads. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Anther development in Arabidopsis can be divided into 14 well-ordered stages on the basis of morphological landmarks32. At stage 8, the microspores are released from tetrads. The tek microspores were rounder and larger than those of wild type. At stage 9, microspores of wild-type plant became vacuolated, whereas the cytoplasm of tek microspores was shrunken and disintegrated. During stage 10–12, microspores of wild type underwent asymmetric mitotic divisions and gradually developed into mature pollen grains. In the mutant, the microspore cytoplasm further degenerated and finally all microspores were aborted at stage 12 (Fig. 1e). These results show that the defective microspore production during microgametogenesis causes the complete male sterility of tek plant.

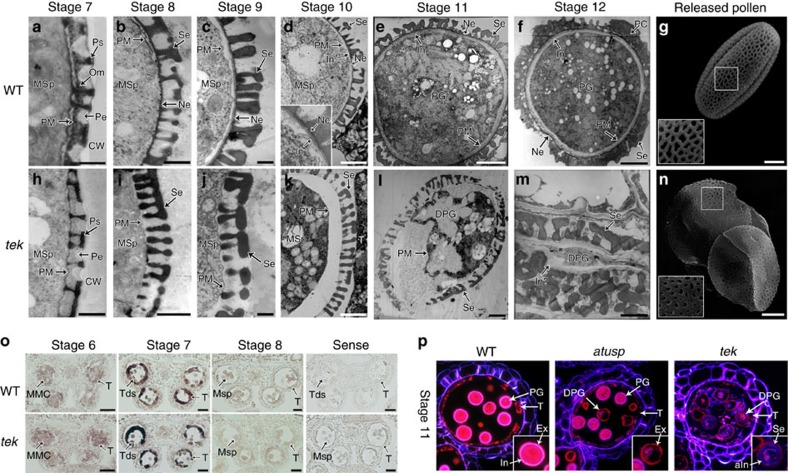

Nexine and intine layers are absent in tek

The pollen wall pattern is determined by several essential events at tetrad stage, including callose deposition, primexine matrix secretion and plasma membrane undulation33,34,35,36,37. These events were indistinguishable between wild type and tek. The pro-sexine could be observed in both wild type and tek. However, accumulation of osmiophilic materials was significantly reduced in periplasmic space on the surface of microspores in tek at later tetrad stage (Fig. 2a,h). When callose wall is totally dissolved at stage 8, the nexine layer was clearly present in wild type (Fig. 2b) but completely lacking in the tek microspores (Fig. 2i). In wild-type microspores, the intine layer between the nexine and the microspore plasma membrane could be clearly detected at stage 10 (Fig. 2d), and continues to increase in thicknesses as the pollen grains mature (Fig. 2e,f). In tek anthers, both the nexine and intine were absent despite the formation of a normal sexine (Fig. 2j). Later, the lack of nexine and intine in tek was more distinct (Fig. 2k,l). By stage 12, all pollen grains of the mutant had collapsed, with the framework of the sexine still visible. Some materials with low electronic density were also observed under the sexine layer (Fig. 2m). The surface pattern of the sexine layer in tek was similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 2g–n), although the shape of the reticulum was slightly different, perhaps as a result of pollen collapse. These results show that the tek mutant failed to develop both nexine and intine, causing microspore abortion and male sterility.

Figure 2. Nexine and intine layers are absent in tek (a–n).

TEM images of pollen wall development in wild type (a–f) and tek (h–m) from stage 7–12. (a,h) Later stage 7, showing the osmiophilic materials is reduced in tek; (b,i), stage 8, showing the nexine layer is absent in tek; (c,j), stage 9; (d,k), stage 10, showing the intine commenced in wild type; (e,l), stage 11, showing the degenerated tek pollen grain; (f,m), stage 12, showing the sexine and material analogues of intine still visible in tek. Scale bars, 500 nm (a–c and h–j); scale bars, 2 μm (d–f and k–m). Scanning electron microscopy of pollen grain of wild-type (g) and tek (n) showed the similar reticulate pattern. Scale bars, 5 μm. (o) AtUSP had its similar expression pattern in wild-type and tek anthers. Scale bars, 20 μm. (p) Cytochemical staining of semi-thin sections of wild-type, atusp/+ and tek. All wild-type pollens showed a pink fluorescent ring of the intine layer, while the half pollens of atusp/+ showed the absence of intine layer. A dim blue fluorescent ring was detected in the degraded pollen of tek. aIn, abnormal intine; Ca, callose wall; DPG, degenerated pollen grain; In, intine; In?, intine-like materials; MMC, microspores mother cell; MSp, microspore; Ne, nexine; PC, pollen coat; Pe, primexine; PG, pollen grain; PM, plasma membrane; Ps, pro-sexine; Se, sexine; T, tapetum; Tds, tetrads.

Intine deposition is dependent on the presence of nexine

Intine development is gametophytically controlled38,39,40. To understand how the sporophytic gene TEK affects the development of intine, we analysed the expression of an intine related gene in tek. Arabidopsis UDP-sugar pyrophosphorylase (AtUSP) was reported to play a critical role in intine synthesis40. The expression level of AtUSP in tek was similar to that of wild type (Supplementary Table 1). In situ hybridization confirmed that the expression pattern of AtUSP was not affected in tek (Fig. 2o). We used Tinopal and diethyloxadicarbocyanine iodide (DiOC2) to stain the intine and exine, respectively (Fig. 2p). In wild type, the intine showed a distinct fluorescent ring between the exine and cytoplasm of pollen. In the locule of atusp/+, half of the microspores (atusp) are abnormal (Supplementary Fig. 1). The fluorescent ring of intine was not observed in the atusp pollen (Fig. 2p). In tek, a dim fluorescent ring (aIn) appeared between exine and cytoplasm of pollen. It is likely to be that the materials required for intine formation can be synthesized in tek microspores. However, the deposition of intine is affected by the absence of nexine in tek microspores, suggesting that intine deposition relies on the presence of the nexine layer.

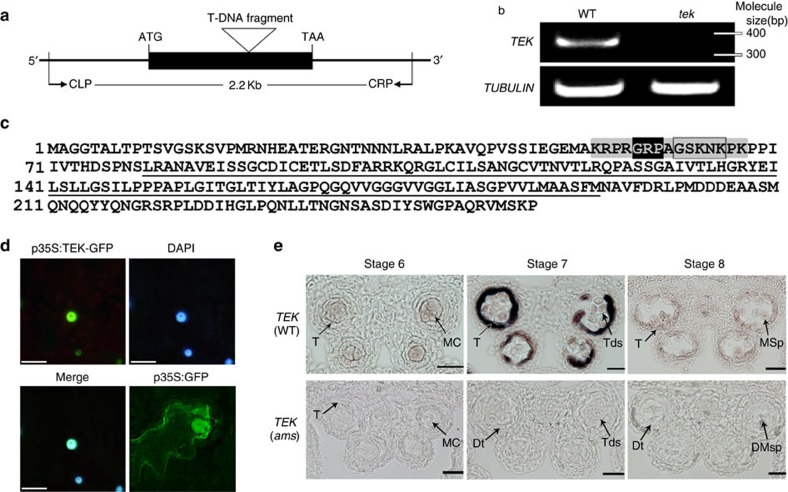

TEK is highly expressed in tapetal cells at tetrad stage

To ascertain the insert location of T-DNA tag, thermal asymmetric interlaced TAIL–PCR41 was carried out and a genomic DNA fragment flanking the left border of T-DNA was recovered. Sequencing of the TAIL–PCR product showed that the T-DNA was inserted in the only exon of At2g42940, which completely abolished the expression of At2g42940 (Fig. 3b). For genetic complementation, we cloned the 2,277-bp genomic region, including the promoter and 3′-untranslated region of At2g42940 from wild type and transformed it into the tek/+ heterozygous plants. Of the 20 transgenic plants with tek/tek genotype, 19 plants showed the normal fertility (Fig. 1a). Our results demonstrated that At2g42940 was TEK and the phenotypes were caused by the disruption of At2g42940.

Figure 3. TEK is highly expressed in tapetal cells in anther.

(a) TEK (At2g42940) contained only one exon (black box). The T-DNA insertion site was indicated and DNA fragment for complementation was outlined by primers CLP and CRP. (b) The TEK transcript could not be detected in tek inflorescence. (c) Amino acid sequence of TEK contained the PPC domain (underlined) and the AT-hook motif (grey) within GRP motif (black) and type I AT-hook motif (boxed); (d) the fluorescence co-localization of p35S:TEK-GFP and DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) indicated TEK was located to the nuclear. The p35S:GFP was used as a control. Scale bars, 10 μm. (e) TEK transcript was mainly detected in tapetal cell at stage 7 in wild-type, whereas this signal could not be detected in ams mutant. Stage 5–7, scale bars, 20 μm; Stage 8–11, scale bars, 50 μm.

TEK encodes an AHL protein with a type I AT-hook motif for matrix attachment region binding and a PPC (Plants and Prokaryotes Conserved) domain evolutionarily conserved in the plant kingdom (Fig. 3c). In Arabidopsis, AHL family contains 29 members of 2 subgroups42 and TEK (AHL16) forms a distinct clade in subgroup I (Supplementary Fig. 2b). TEK homologues exist in both monocots and dicots. In some plants, such as rice and Medicago, there was only one closely related homologue, while two homologues were identified in Populus and soybean (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Arabidopsis AHL family was reported to be located in the nucleus43. We transformed tobacco leaves with p35S:TEK-GFP and found that the fluorescence of the TEK-GFP protein was co-localized with the 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining in nuclei (Fig. 3d), indicating that TEK is localized in the nuclear region.

Reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT–PCR) analysis showed that TEK was widely expressed in flowers, roots and stems, with relatively low expression in leaves (Supplementary Fig. 2a). As TEK functions in anther development, we carried out in situ hybridization to detect its spatial and temporal expression pattern in wild-type anthers (Fig. 3e). During meiosis (stage 6), a weak hybridization signal was observed in microspore mother cells and tapetum. At the tetrad stage (stage 7), the maximum hybridization signal was seen in the tapetal cells with weak signal in the tetrads. At stage 8, with the microspores released from the tetrad, TEK expression was dramatically reduced in both tapetum and microspores. Thereafter, a hybridization signal was no longer observed. The expression pattern of TEK is in agreement with its function for pollen wall formation during anther development.

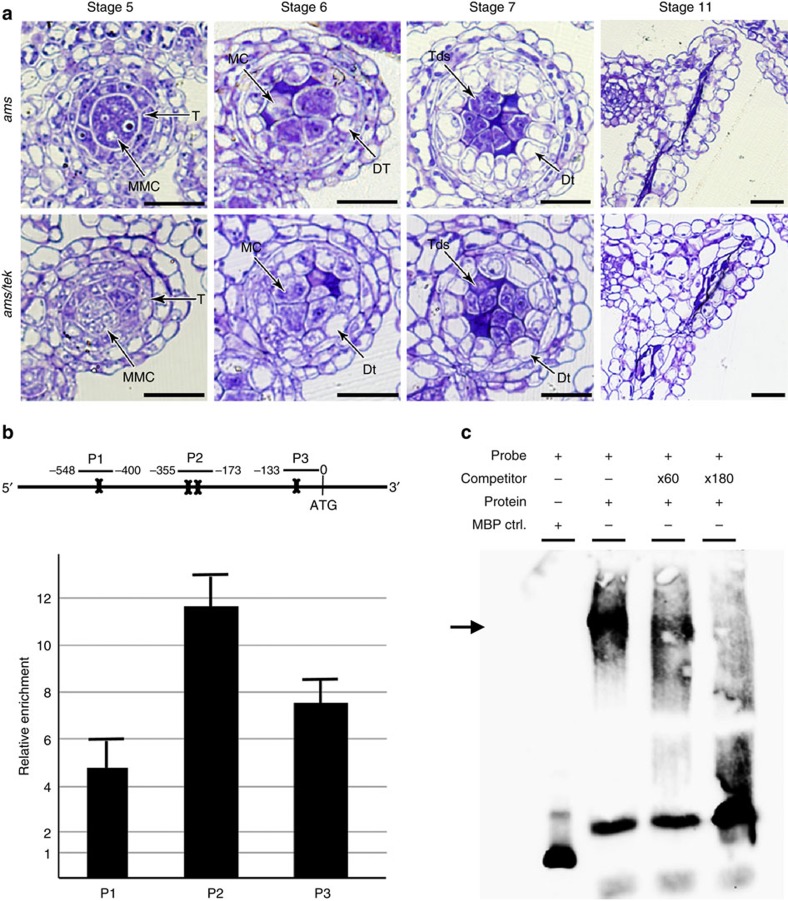

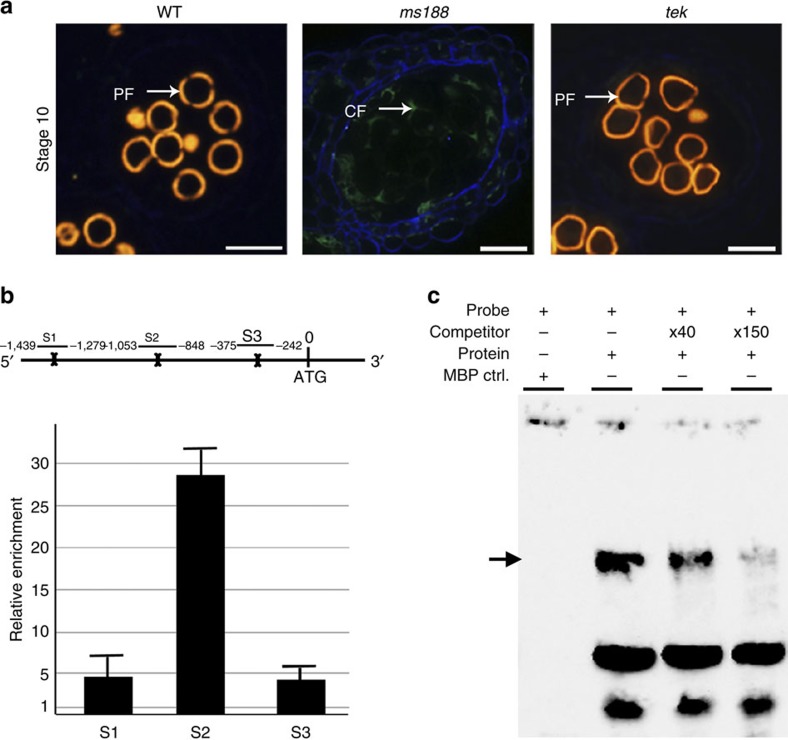

AMS directly binds the promoters of TEK and MS188

In the tapetum of Arabidopsis, there is a genetic pathway of DYT1-TDF1-AMS- MYB103-MS1, which is essential for tapetum development and function24. As TEK is mainly expressed in the tapetum at stage 7 (Fig. 3e), we performed in situ hybridization using TEK probe to further understand its position of the genetic pathway. We found that TEK signal could not be detected in ams anther, whereas the expression of TEK is not affected in ms188, supporting the hypothesis that TEK expression was under the regulation of AMS (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 4). We constructed double mutant of ams tek (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). The ams tek plant showed male sterile phenotype with normal vegetative growth (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The defective phenotype of tapetal development in the double mutant was similar to ams (Fig. 4a). These results show that TEK genetically acts downstream of AMS in the tapetum.

Figure 4. AMS directly binds to the promoter of TEK.

(a) Sections of anther development show the phenotype of ams tek double mutant is similar with ams, indicating TEK functions downstream of AMS. DMSp, degenerated microspores; Dt, degenerated tapetum; MC, meiotic cell. Scale bars, 20 μm. (b) The TEK promoter region contains four predicted E-boxes (bone). The enrichments of TEK promoter were confirmed by ChIP–quantitative PCR (qPCR) with the primer sets (P1, P2, P3). Fold enrichment calculations from two replicates qPCR assays in three independent ChIP experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (n=3). (c) EMSA assay shows AMS can bind to P2 fragment in the TEK promoter. Non-labelled competitors are able to reduce the visible shift significantly (arrow).

To analyse whether AMS directly regulates TEK expression in vivo, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis. AMS was reported to bind to the sequence containing E-box (CANNTG)12. There are four E-box motifs in the TEK promoter region (−29 to −24, −236 to −231, −262 to −257 and −506 to −501) (Fig. 4b). Polyclonal antibodes against AMS was used for ChIP with wild-type inflorescence. Enrichments were detected with three primer sets in TEK promoters, showing that TEK was positively enriched in +AB (antibody) compared with –Ab samples (Fig. 4b). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was further performed to confirm the quantitative ChIP–PCR results in vitro. The full-length AMS was cloned into the pMAL plasmid and the recombinant AMS protein was purified from the supernatant. AMS protein can bind to the TEK promoter fragment (−294 to −12) with the supershift band. A 60-fold and a 180-fold excess of unlabelled TEK promoter fragment gradually competed for AMS and significantly reduced the supershifted band. In the negative control, no parallel shift band was detected with the maltose binding protein (MBP) tag only (Fig. 4c). These data show that AMS directly binds to the E-box regions in TEK promoter, suggesting AMS might regulate TEK expression for nexine formation.

Sexine autofluorescence can be directly observed under the ultraviolet light. In wild-type and tek, the autofluorescence was clearly observed, indicating the existence of the sexine layer. However, this autofluorescence can not be detected in the ms188 mutant (Fig. 5a), further supporting the previous transmission electron microscopic (TEM) observation11 that the sexine layer is completely abolished in ms188. Previous data showed that MS188 was not expressed in ams mutants, and that the phenotypes of ms188 ams double mutants were similar to those of ams instead of ms188 (ref. 24). Using ChIP and EMSA analysis, we found that AMS can also bind to the MS188 promoter (Fig. 5b,c). In addition, the expression of TEK and MS188 was not affected by each other (Supplementary Fig. 4). Microarray data show that genes responsible for the sexine are not affected by TEK (Supplementary Table 1). Thus, these results suggest that sexine and nexine formation are independent, although both are under control of AMS in the tapetum.

Figure 5. AMS directly binds to the promoter of MS188.

(a) Cytochemical staining of anther sections show autofluorescence of sexine in wild-type and tek but not in ms188. CF, callose fluorescence; PF, pollen wall autofluorescence. Scale bars, 20 μm. (b) The enrichments of MS188 promoter were confirmed by ChIP–quantitative PCR (qPCR) with the primer sets (S1, S2, S3), suggesting MS188 is a direct target of AMS. Fold enrichment calculations from two replicates qPCR assays in three independent ChIP experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (n=3). (c) EMSA assay shows AMS is able to bind to S2 fragment in the MS188 promoter. Non-labelled competitors are able to reduce the visible shift significantly (arrow).

Discussion

Nexine is a conserved structure of the pollen wall in vascular land plants based on the observation under TEM4,13,14,15. In this work, TEM analysis showed that osmiophilic materials were accumulated in periplasmic space on the surface of microspores in wild type. Later, the nexine layer was quickly formed surrounding the microspore surface after microspore released from the tetrad. However, the nexine formation had not been detected in tek and sexine failed to adhere or anchor to the microspore surface. In addition, the intine was absent in tek; however, the intine gene expression was not affected and the materials for intine formation seemed to be synthesized. These results indicate that TEK acts as a regulator controlling nexine formation during pollen development. The intine formation is gametophytically controlled38,39,40. However, the TEK gene was expressed in the tapetum under sporophytic control. Thus, we suppose that the intine formation depends on the presence of the nexine, which is consistent with the fact that the intine is formed after the nexine during the pollen wall development. This work provides a potential material for further investigation of nexine formation and function.

TEK encodes a member of the AHL family protein. It is reported to function in the maintenance of genome integrity by silencing transposable element and repeat-containing genes in Ler ecotype31. However, the function of TEK in relation to pollen development has not been investigated. Our results demonstrate that TEK is essential for nexine formation. The members of the AHL family, including AHL16 (TEK), AHL21 (GIK), AHL25 (AGF1) and AHL15 (AGF2), were reported to maintain genome integrity. They also act as a molecular node to regulate the downstream gene expression through binding to the cis-acting sequence44,45. TEK is likely to regulate the expression of genes essential for the nexine formation. The identification of these target genes of TEK should facilitate the understanding of the nexine composition and function.

Recent investigations revealed that several tapetal-specific genes participated in exine formation, such as ACOS5, CYP703A2/704B1, TKPR1/2, LAP5/6 and MS2 for sporopollenin biosynthesis16,17,18,19,20,21,22 and ABCG26 for precursor transportation27,28,29. However, the molecular mechanisms how these tapetal genes regulate exine development are not clear. As regulatory genes were identifed in tapetal genetic pathway (DYT1-TDF1-AMS-MS188-MS1), the identification of other pollen wall-related genes would further reveal elaborate mechanism for tapetum to control the synthesis and transportation of exine materials. In this work, we found that AMS can directly bind to TEK promoter, showing that the regulatory pathway (DYT1-TDF1-AMS-TEK) in tapetum is required for nexine layer formation. On the other hand, MS188 is the key regulator for sexine formation. Therefore, the direct binding of AMS to MS188 promoter represents the tapetal regulatory pathway (DYT1-TDF1-AMS-MS188) for sexine layer formation. These two genetic pathways in the tapetum strongly confirm the previous studies that exine, including both sexine and nexine, is sporophytically controlled by the tapetum8,9,10,11,12.

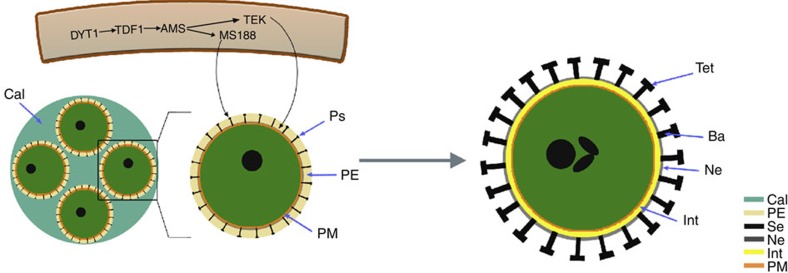

The molecular cloning of TEK and identification of the genetic pathways for pollen wall formation allow us to further understand the pollen wall development (Fig. 6). As both the key regulators Male Sterile 188 (MS188) and TEK for sexine and nexine formation, respectively, are directly targeted by AMS, the formation of sexine and nexine probably initiates at the same time inside the tetrad. TEM analysis showed the absence of sexine in ms188 mutant with normal nexine layer11 and the normal sexine in tek mutant without nexine. In addition, the expression of MS188 is independent of TEK. All these suggest that these two layers are independently formed, although both of them are under regulation of AMS. The nexine layer is already formed when microspores are released from the tetrad, while sporopollenin continues to accumulate outside the nexine to form the mature sexine. The intine is formed after the nexine, which can be observed at stage 10. We propose that the nexine may play a role in protecting the released microspore until the intine is formed and act as a template for the accumulation of materials during intine formation.

Figure 6. Diagrammatic representation of the pollen wall development.

The AMS activated the expression of MS188 and TEK in tapetum. In tetrad, four microspores were surrounded by callose. The materials produced in tapetum were transported to form the pro-sexine and nexine in the primexine. The mature pollen wall contains sexine (bacula and tectum), nexine and intine layers. Ba, bacula; Cals, callose; Int, intine; Ne, nexine; PE, primexine; PM, plasmamembrane; Ps, pro-sexine; SE, sexine; Tet, tectum.

Methods

Plant material

Arabidopsis, ecotype Columbia-0, was the source of both the wild-type and mutant plants. Plants were grown under long-day conditions (16-h of light/8-h of dark) in a growth room at ~22 °C. The tek mutant was isolated from T-DNA lines provided by Dr Zu-hua He. The herbicide Basta was used to monitor the segregation of the T-DNA inserts.

Microscopy

Plants were photographed with a Cybershot T-20 digital camera (Sony, Japan). Flower images were taken using a dissecting microscope with an DP70 digital camera (Olympus, Japan). Alexander’s solution was made by the following reagents46: ethanol, 10 ml; 1% malachite green in 95% ethanol, 1 ml; distilled water, 50 ml; glycerol 25 ml; phenol, 5 g; chloral hydrate, 5 g; acid fuchsin 1% in water, 5 ml; orange G, 1% in water 0.5 ml and glacial acetic acid, 1–4 ml. Staining the anthers overnight at room temperature. Plant material for the semi-thin sections was prepared and embedded in Spurr’s resin47. Semi-thin sections were prepared by cutting the plant material into 1-μm thick sections, and then were stained and photographed by bright-field microscopy. For intine layer observation, the sections were stained with Toluidine blue 5 min (10 mg ml−1), Tinapol 15 min (10 μg ml−1) (Sigma, USA) and DiOC2 5 min (5 μl ml−1) (Sigma). For scanning electron microscopic examination, fresh pollen grains were coated with 8 nm of gold and observed under JSM-840 microscopy (JEOL, Japan). For TEM observation, the same-stage buds of wild type and mutant grown at the same condition were dissected to avoid experimental deviation. Arabidopsis buds from the inflorescence were fixed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (v/v), then washed several times before being dehydrated through a series of acetone/water mixtures. Finally, the flower buds were embedded into the fresh mixed resin and polymerized in molds (60 °C, 24 h)37. Ultrathin sections (70–100 nm thick) were observed using TEM microscopy (JEOL, Japan). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence was detected under an IX70 inverted microscope system (Olympus).

Identification and complementation of the TEK gene

The identification of the T-DNA insertion was performed using primers that specifically amplify the BAR gene of T-DNA (Bar-F and Bar-R). For TAIL–PCR, the T-DNA left border primer (AtLB1, AtLB2 and AtLB3), and genomic DNA of the mutant plants were used. Identification of the T-DNA insertion site was analysed with AtLB3 and plant-specific primers (ILP and IRP). A DNA fragment of 2,277 bp, including 725 bp upstream and 778 bp downstream sequences, was amplified by primers of CLP-F and CRP-R using KOD polymerase (Takara Biotechnology, Japan). The fragment was cloned into a pCAMBIA1300 binary vector (CAMBIA, Australia) and verified by sequencing. The plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and then introduced into the heterozygous mutant plants. Transformants were selected using 20 mg l−1 hygromycin. The backgrounds of the transformants were verified by primers of AtLB3, IRP, CLPV-F and CRPV-R. Oligonucleotide sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Expression analysis and in situ hybridization

Full-length complementary DNA of the TEK cloned from wild-type plants without the stop codon was cloned for the GFP fusion with primers GFP-F and GFP-R. The PCR product was cloned into the PMON530 vector with enhanced GFP and transformed into newly formed tobacco leaves with injection48; the GFP fluorescence of transgenic plants was observed with a Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope. For RT–PCR, RNA was extracted from the root, stem, rosette leaves, 21-day-old seedlings and inflorescences using a Trizol kit (Invitrogen, USA). RT–PCR for 28 cycles was used to analyse the expression level of the TEK gene by primers (RTTEK-F and RTTEK-R). Non-radioactive RNA in situ hybridization was performed with using the Digoxigenin RNA Labeling Kit (Roche, USA) and the PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche). A 450-bp TEK cDNA fragment was amplified using TEK-specific primers (TEK-F and TEK-R). A 417-bp fragment was amplified using AtMYB103-specific primers (MS188-F and MS188-R). A 334-bp fragment was amplified using AtUSP-specific primers (USP-F and USP-R). The PCR products were cloned into the pbluescriptSK vector and confirmed by sequencing. Plasmid DNA were completely digested and used as the template for transcription with T3 or T7 RNA polymerase, respectively49. Oligonucleotide sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Microarrays

Closed buds collected from wild-type and tek mutant plants were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Three biological replicates of independently grown materials were used. Total RNA was amplified and labelled by Low RNA Input Linear Amplification kit (catalogue number 5184-3523, Agilent Technologies, USA), 5-(3-aminoallyl)-UTP (catalogue number AM8436, Ambion, USA), Cy3 NHS ester (catalogue number PA13105, GE Healthcare Biosciences, USA), Cy5 NHS ester (catalogue number PA15100, GE Healthcare Biosciences) followed the manufacturer’s instructions. Labelled cRNA were purified by RNeasy mini kit (catalogue number 74106, QIAGEN, Germany). Each 44 K Arabidopsis oligo microarray slide was hybridized with 825 ng Cy3-labelled cRNA and 825 ng Cy-5 labelled cRNA using Gene Expression Hybridization Kit (catalogue number 5188-5242, Agilent Technologies) in Hybridization Oven (catalogue number G2545A, Agilent Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were scanned by Agilent Microarray Scanner (catalogue number G2565BA, Agilent Technologies) and Feature Extraction software 10.7 (Agilent Technologies) with default settings. Raw data were normalized by Lowess (locally weighted scatter plot smoothing) algorithm, Gene Spring Software 11.0 (Agilent Technologies). The spots that displayed an expression ratio (tek/wild type) of <0.5 (for downregulated genes) and >2 (for upregulated genes), a Signal/Noise value >2.6 and a pValueLogRatio <0.05 in three independent experiments were selected.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP assay was performed according to ref. 50 with minor modifications. A total of 0.8–1.0 g inflorescence of wild-type plant were collected and crosslinked in the buffer containing formaldehyde. After isolating the nuclei and shearing the chromatin with ultrasonic, the majority of the DNA fragments have a size between 200–800 bp. After pre-immuneserum with sheared salmon sperm DNA/proteinA agarose mix (Millipore, USA) for 1 h, the supernatants were incubated with polyclonal antibody against AMS (GL Biochem, China) at 4 °C overnight with 1:100 dilution. Forty microlitres of magnetic beads protein G (Invitrogen) were added to precipitate the antibody–protein/DNA complexes. The DNA fragments were eluted after reverse crosslinking by boiling at 100 °C for 10 min. The remaining steps for purification of DNA were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR were performed on an ABI PRISM 7300 detection system (Applied Biosystems, USA) with SYBR Green I master mix (TOYOBO, Japan)51. All PCR experiments were performed as the following conditions: 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 62 °C for 1 min. Under the same conditions, we calculated the ΔCt values (Ct of each sample−Ct of the NoAb control) and took 2−ΔCt as the fold enrichment. The relevant primers were listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

To obtain purified AMS protein for the EMSA experiments, the full-length fragment of the AMS gene was amplified using the primer pairs AMSpMAL-F and AMSpMAL-R, and cloned into the pMAL-p5X vector (NEB, USA) to produce the (Maltose Binding Protein) MBP-AMS construct. Expression and purification of the fusion protein were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA fragment containing the E-box (CANNTG) in the TEK and MS188 regulatory region were generated by specific primers (ETEK-F/ETEK-R and EMS188-F/EMS188-R) that were used to generate a biotin-labelled and competitor probe, respectively. The EMSA assay was performed with a LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Reactions were performed in binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol), at room temperature for 20 min. The subsequent processes were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The image was caught by Tanon-5500 Chemiluminescent Imaging System (Tanon, China).

Protein structure prediction and phylogenetic analysis

The TEK protein sequence was used to search for TEK homologues using BLAST. Multiple sequence alignment of full-length protein sequences was performed using ClustalX 2.0. Phylogenetic trees were constructed and tested by MEGA3.1 based on the neighbour-joining method ( http://www.megasoftware.net/).

Author contributions

The project leader is Z.-N.Y. X.-F.U. contributed Figs 1, 2a–n,p, 3, 4a, 5a. Y.L. and X.-F.X. contributed Figs 4b,c, 5b,c. J.-N.G. contributed Fig. 2p and construction of the MBP-AMS fusion plasmid. J.Z. contributed Fig. 6. X.-F.X., J.Z. and Y.L. designed the experiments. Y.L. and J.Z. wrote the paper together. S.B. contributed to interpretation and discussion of the observations.

Additional information

Accession codes: Microarray data has been deposited in GEO repository under accession number GSE56497.

How to cite this article: Lou, Y. et al. The tapetal AHL family protein TEK determines nexine formation in the pollen wall. Nat. Commun. 5:3855 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4855 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2013CB945100), the National Science Foundation of China (31100227). We thank Professor Sheila McCormick and Professor Yunde Zhao for critical reading and revising of the manuscript.

References

- Scott R. J. in:Molecular and Cellular Aspects of Plant Reproduction eds Scott R. J., Stead M. A. 49–81University Press (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Zinkl G. M., Zwiebel B. I., Grier D. G. & Preuss D. Pollen-stigma adhesion in Arabidopsis: a species-specific interaction mediated by lipophilic molecules in the pollen exine. Development 126, 5431–5440 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariizumi T. et al. Disruption of the novel plant protein NEF1 affects lipid accumulation in the plastids of the tapetum and exine formation of pollen, resulting in male sterility in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 39, 170–181 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore S., Wortley A. H., Skvarla J. J. & Rowley J. R. Pollen wall development in flowering plants. New Phytol. 174, 483–498 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilford W. J., Schneider D. M., Labovitz J. & Opella S. J. High resolution solid state C NMR spectroscopy of sporopollenins from different plant taxa. Plant Physiol. 86, 134–136 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R. J., Spielmana M. & Dickinsonb H. G. Stamen structure and function. Plant Cell 16, 46–60 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J. Origin of exine. Nature 195, 1069–1071 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson H. G. & Heslop-Harrison J. Common mode of deposition for the sporopollenin of sexine and nexine. Nature 220, 926–927 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani C., De Beuckeleer M., Truettner J., Leemans J. & Goldberg R. B. Induction of male sterility in plants by achimeric ribonuclease gene. Nature 347, 737–741 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Piffanelli P., Ross J. H. E. & Murphy D. J. Biogenesis and function of the lipidic structures of pollen grains. Sex Plant Reprod. 11, 65–80 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. B. et al. Transcription factor AtMYB103 is required for anther development by regulating tapetum development, callose dissolution and exine formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 52, 528–538 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. et al. The ABORTED MICROSPORES regulatory network is required for postmeiotic male reproductive development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22, 91–107 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdtman G. Pollen walls and angiosperm phylogeny. Bot. Notiser. 113, 41–45 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- Hesse M. et al. Pollen terminology: An Illustrated Handbook Springer (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. & Ulrich S. The endexine: a frequently overlooked pollen wall layer and simple method for detection. Grana 49, 83–90 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- de Azevedo Souza C. et al. A novel fatty Acyl-CoA synthetase is required for pollen development and sporopollenin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 507–525 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morant M. et al. CYP703 is an ancient cytochrome P450 in land plants catalyzing in-chain hydroxylation of lauric acid to provide building blocks for sporopollenin synthesis in pollen. Plant Cell 19, 1473–1487 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobritsa A. A. et al. CYP704B1 is a long-chain fatty acid omega-hydroxylase essential for sporopollenin synthesis in pollen of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 151, 574–589 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobritsa A. A. et al. LAP5 and LAP6 encode anther-specific proteins with similarity to chalcone synthase essential for pollen exine development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 153, 937–955 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. et al. Male Sterile2 encodes a plastid-localized fatty acyl carrier protein reductase required for pollen exine development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157, 842–853 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grienenberger E. et al. Analysis of TETRAKETIDE α-PYRONE REDUCTASE function in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a previously unknown, but conserved, biochemical pathway in sporopollenin monomer biosynthesis. Plant Cell 22, 4067–4083 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. S. et al. LAP6/POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE A and LAP5/POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE B encode hydroxyalkyl-pyrone synthases required for pollen development and sporopollenin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22, 4045–4066 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. Molecular genetic analyses of microsporogenesis and microgametogenesis in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56, 393–434 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Lou Y., Xu X. & Yang Z. N. A genetic pathway for tapetum development and function in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 53, 892–900 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. et al. Regulation of Arabidopsis tapetum development and function by DYSFUNCTIONAL TAPETUM1 (DYT1) encoding a putative bHLH transcription factor. Development 133, 3085–3095 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. et al. Defective in Tapetal Development and Function 1 is essential for anther development and tapetal function for microspore maturation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 55, 266–277 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilichini T. D., Friedmann M. C., Samuels A. L. & Douglas C. J. ATP-binding cassette transporter G26 is required for male fertility and pollen exine formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154, 678–690 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. et al. An ABCG/WBC-type ABC transporter is essential for transport of sporopollenin precursors for exine formation in developing pollen. Plant J. 65, 181–193 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou X. Y. et al. WBC27, an adenosine tri-phosphate-binding cassette protein, controls pollen wall formation and patterning in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 53, 74–88 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin G. et al. Obtaining and analysis of flanking sequences from T-DNA transformants in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 165, 941–949 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. et al. A matrix protein silences transposons and repeats through interaction with retinoblastoma-associated proteins. Curr. Biol. 23, 345–350 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders P. M. et al. Anther developmental defects in Arabidopsis thaliana male-sterile mutants. Sex Plant Reprod. 11, 297–322 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J. Wall pattern formation in angiosperm microsporogenesis. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 25, 277–300 (1971). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon J. M. & Dickinson H. G. Determination of patterning in the pollen wall of Lilium henryi. J. Cell Sci. 63, 191–208 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore S. & Barnes S. Pollen wall morphogenesis in Tragopogon porrifolius (Compositae: Lactuceae) and its taxonomic significance. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 52, 233–246 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Southworth D. & Jernstedt J. A. Pollen exine development precedes microtubule rearrangement in Vigna unguiculata (Fabaceae): a model for pollen wall patterning. Protoplasma 187, 79–87 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. S. et al. No primexine and plasma membrane undulation is essential for primexine deposition and plasma membrane undulation during microsporogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158, 264–272 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yu M., Geng L. L. & Zhao J. The fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein gene, FLA3, is involved in microspore development of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 64, 482–497 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. et al. The polygalacturonase gene BcMF2 from Brassica campestris is associated with intine development. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 301–313 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr J. A., Storey K. K., Jung H. J., Somers D. A. & Gronwald J. W. UDP-sugar pyrophosphorylase is essential for pollen development in Arabidopsis. Planta 224, 520–532 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. G., Mitsukawa N., Oosumi T. & Whittier R. F. Efficient isolation and mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA insert junctions by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR. Plant J. 8, 457–463 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L. & Landsman D. AT-hook motifs identified in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 4413–4421 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto S. et al. Identification of a novel plant MAR DNA binding protein localized on chromosomal surfaces. Plant Mol. Biol. 56, 225–239 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K. H., Yu H. & Ito T. AGAMOUS controls GIANT KILLER, a multifunctional chromatin modifier in reproductive organ patterning and differentiation. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000251 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita A., Furumoto T., Ishida S. & Takahashi Y. AGF1, an AT-hook protein, is necessary for the negative feedback of AtGA3ox1 encoding GA 3-oxidase. Plant Physiol. 143, 1152–1162 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M. P. Differential staining of aborted and nonaborted pollen. Stain Technol. 44, 117–122 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen H. ,A. & Makaroff C. A. Ultrastructure of microsporogenesis and microgametogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. ecotype Wassilewskija (Brassicaceae). Protoplasma 185, 7–21 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Vionnet M. & Rostan O. [Idiopathic spontaneous hemoperitoneum]. Swiss Surg. 9, 184–186 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y. F. et al. RUPTURED POLLEN GRAIN1, a member of the MtN3/saliva gene family, is crucial for exine pattern formation and cell integrity of microspores in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147, 852–863 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C. et al. Chromatin techniques for plant cells. Plant J. 39, 776–789 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. et al. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 is essential for pollen wall pattern formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 162, 720–731 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary References