Abstract

Type 1 phototherapeutic agents based on diarylamines were assessed for free radical generation and evaluated in vitro for cell death efficacy in the U937 leukemia cancer cell line. All of the compounds were found to produce copious free radicals upon photoexcitation with UV-A and/or UV–B light, as determined by electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy. Among the diarylamines, the most potent compounds were acridan (4) and 9-phenylacridan (5), with IC50 values of 0.68 μM and 0.17 μM, respectively.

Keywords: Diarylamines, ROS, type 1, type 2, photosensitizers, radicals, ESR

The hallmark of phototherapy is its ability to destroy lesions with minimal or negligible effect on normal tissues. Furthermore, the cosmetic effect achieved after phototherapy of head and neck and skin cancers has been remarkable.1,2 As is commonly known, phototherapeutic agents operate via two principal mechanisms, type 1 and type 2,3−5 and all the clinically used photosensitizers operate via a type 2 process mediated by singlet oxygen. We have been directing our efforts on the development of novel type 1 phototherapeutic agents to complement the currently used type 2 (PDT) agents and enhance the phototherapy arsenal. Type 1 agents encompass wider classes of compounds than those of type 2 because type 1 photosensitzers can cause cell death either via direct interaction of the excited photosensitizer with the tissue or indirectly through the generation of secondary reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as the superoxide radical anion, hydroxyl radical, hydroperoxyl radical, or hydrogen peroxide.6 Type 1 photosensitizers can be excited using any wavelength of light; albeit, visible light is preferred for clinical use. In the type 2 process, the energy of the excited photosensitizer is first transferred to the oxygen to generate reactive singlet oxygen that causes cell death. The type 2 process requires the light of wavelength 600–700 nm (red light) range for efficient generation of singlet oxygen.

In the previous paper7 on type 1 photosensitizers, we reported that sulfenamides, which contain a labile S–N bond, underwent photofragmentation to produce S- and N-centered radicals, and that the N-centered radicals formed initially upon photofragmentation could either induce cell death directly or, in the presence of oxygen, form stable nitroxyl radicals along with ROS. It has been shown that aromatic nitroxyl radicals can intercalate into DNA and cause single strand breakage.8 Interestingly, aliphatic nitroxyl radicals, in contrast, are known to be cell protectors against oxidative stress.9 The results of this study on sufenamides,7 and previous ESR and laser flash photolysis studies on diraylamines,10−16 prompted us to investigate whether diarylamines by themselves would be useful as a type 1 phototherapeutic agent. Accordingly, in this paper, we report the cell viability and ESR results of various diarylamines 1–12 exposed to UV-A/UV-B light (Figure 1). Interestingly, the phototoxicity of amitriptyline, a tertiary diarylamine akin to 7, is due to the effect of superoxide anion,17 which can be postulated to have been generated via the type 1 process. The diarylamines 1–4, 6, 8, 9, 10, and 11 were purchased from commercial sources. The amines 5, 7, and 12 were prepared by published methods.18−20

Figure 1.

Structures of Diarylamines.

The cancer cell viability assays with the diarylamines above in the absence and presence of light were carried out by the same procedure as described in our previous paper.7 The compounds were dissolved in DMSO (8 mM) and diluted with the cell culture media such that the amount of the DMSO exposed to the cells remained below 0.5% (64 mM). The IC50 values (50% decrease in cell viability after exposure to light for 20 min) are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Cell Viability (IC50) of Diarylamines.

| photosensitizer | IC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|

| 1 | N.D.b |

| 2 | 5.56 ± 1.15 |

| 3 | N.D.b |

| 4 | 0.68 ± 0.11 |

| 5 | 0.17 ± 0.01 |

| 6 | N.D.b |

| 7 | N.D.b |

| 8 | 14.5 ± 1.54 |

| 9 | 1.39 ± 0.11 |

| 10 | N.D.b |

| 11 | 2.58 ± 1.14 |

| 12 | N.D.b |

Average of at least three independent runs.

Not determined due to the lack of difference between dark-toxicity and phototoxicity in the entire concentration range.

All of the active diarylamines displayed dose-dependent

and light

exposure time dependent decrease in cell viability. It should be noted

that DMSO itself exhibited cytotoxicity only at high concentration

and at long exposure time to light.7 Representative

cell viability dose–response graphs for the three most active

diarylamines 4, 5, and 11 are

shown in Figures 2–4. Diphenylamine (1) is inactive under

the photolytic conditions employed herein. Connecting the two phenyl

groups with a single bond (compound 2) resulted in a

moderately active compound with an IC50 of about 5 μM.

Insertion of a methylene bridge between the nitrogen and the phenyl

ring (compound 3) completely abrogated the activity.

In sharp contrast, insertion of a methylene bridge between the two

phenyl rings (acridan, 4) resulted in a very potent compound

with an IC50 of about 0.68 μM. Introduction of the

phenyl group in the 9-position in acridan (compound 5) resulted in the most potent compound with IC50 of 0.17

μM. As would be expected, introduction of a carbonyl group at

the 9-position (compound 6) abrogated the activity due

to the deactivating effect of the carbonyl group toward free radical

formation.21 Likewise, N-methylation of

acridan (compound 7) also obviated the activity, clearly

indicating the requirement of the NH group for activity. Replacement

of the methylene group in acridan with oxygen or sulfur produced varied

results. Phenoxazine (8) is weakly active, whereas phenothiazine

(9) is highly active. Indeed, the phenothiazine is one

of the three most potent compounds, with an IC50 of about

1.39 μM. Replacement of the NH group in phenothiazine with a

sulfur atom (compound 13) completely abrogated the activity, confirming that the

nitrogen-centered radical is indeed required for activity. This inactivity

is consistent with the fact that no radicals could be detected by

ESR with 13b or with the parent

thianthrene (13a).22 Insertion of an ethylene bridge between the two phenyl

rings (compound 10) resulted in inactive compound. In

contrast, insertion of a vinylene bridge (compound 11) produced a very active compound with an IC50 of about

2.58 μM. Surprisingly, introduction of an azo bridge (compound 12) completely abrogated the activity.

completely abrogated the activity, confirming that the

nitrogen-centered radical is indeed required for activity. This inactivity

is consistent with the fact that no radicals could be detected by

ESR with 13b or with the parent

thianthrene (13a).22 Insertion of an ethylene bridge between the two phenyl

rings (compound 10) resulted in inactive compound. In

contrast, insertion of a vinylene bridge (compound 11) produced a very active compound with an IC50 of about

2.58 μM. Surprisingly, introduction of an azo bridge (compound 12) completely abrogated the activity.

Figure 2.

Cell viability graph of acridan (4): blue, no light exposure; red, 20 min light exposure.

Figure 4.

Cell viability graph of dibenzazepine 11: blue, no light exposure; red, 20 min light exposure.

Figure 3.

Cell viability graph of 9-phenylacridan (5): blue, no light exposure; red, 20 min light exposure.

All of the diarylamines generated copious free radicals upon photoexcitation, as confirmed by ESR spectroscopy. The properties, lifetimes, and further transformations of the initially formed N-centered radical are obviously dependent on the structure of the corresponding diarylamine from which they had originated. Because most of the free radicals are short-lived, a spin trapping agent, 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO), was used to trap radical species in the ESR studies for some of the compounds. The DMPO spin adducts are relatively stable nitroxides with unique ESR spin parameters and spectral patterns depending on the type of free radicals added to the carbon atom at the 2-position (i.e., the β-carbon) in DMPO.23,24 However, some of the amines, such as 1, 8, 9, and 10, have been shown to produce stable nitroxyl radicals or radical cations10,11 that would not require spin trapping. For illustrative purposes, representative ESR spectra of two of the active compounds, viz., acridan (4) and the azepine 11, are shown in Figures 5 and 6, respectively. It should be noted that the ESR spectrum of photolyzed acridan (4) was obtained in the presence of DMPO but that of the photolyzed azepine 11 was determined without DMPO because the lifetime of the radical (t1/2 = 20 s) from the photolysis of 11 was sufficiently long. The complete discussion of the ESR measurement and spectral analyses of the diarylamines 1–12 will be published separately.

Figure 5.

ESR spectrum of photolyzed acridan (4) with DMPO in benzene solution (deoxygenated with nitrogen gas for 5 min): (a) before irradiation; (b) after irradiation for 2 min. The starred peaks are DMPO/acridan spin adducts (g = 2.0041) with the following splitting paramters: aNσ = 1.423; aHβ = 2.111 mT.

Figure 6.

. ESR spectrum of 5H-dibenz[b,f]azepine (11) without DMPO in benzene solution: (a) sample without deoxygenation; (b) sample purged with nitrogen for 5-min: nitrogen-centered radical (g = 2.0015) with the following fitting parameters: aN = 0.84, aH(2) = 0.42, aH(4) = 0.22, aH(4) = 0.11 mT; the numbers in the parentheses refer to the number of equivalent protons.

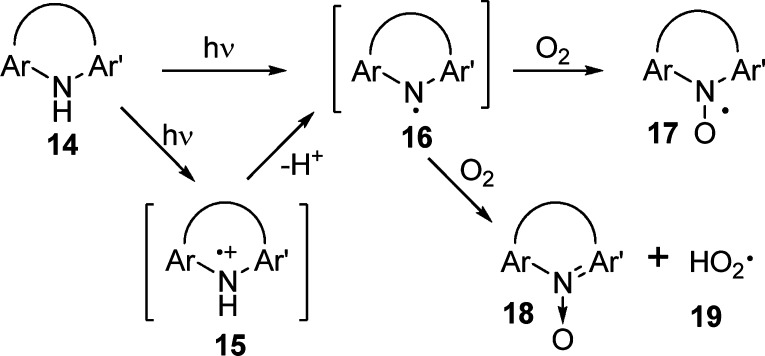

As reported previously,11,16 the laser flash photolysis and ESR studies of diarylamines 14 initially yield the aminyl radical cations 15 or aminyl radicals 16 as primary photoproducts depending on the rigidity of the molecule (Scheme 1). For example, the highly rigid carbazole yields only the radical cation 15 initially, whereas phenothiazine (9) yields only the aminyl radical 16. Acridan (4) gives predominantly the radical cation 15 along with a small amount of the radical 16. Nevertheless, the radical cation 15 is eventually converted to the aminyl radical 16 upon deprotonation, and the resulting aminyl radical 16 may induce tissue damage directly or undergo further reaction with oxygen to form the nitroxyl radical 17 and the hydroperoxyl radical 19.10,11,25

Scheme 1.

The differences in activity among the diarylamines can be rationalized on the basis of transition states leading to the formation of reactive intermediates. In the case of diphenyamine (1) versus carbazole (2), the difference could be attributed to better electron delocalization of the N-centered radical (or radical cation) in carbazole compared to diphenylamine, and the ability of planar carbazole to intercalate in the DNA framework. The sharp difference in cell viability between dihydrophenanthridine (3) and acridan (4) can be explained by the mechanism outlined in Scheme 2. In the case of acridan, the nitroxyl radical may undergo facile hydrogen abstraction by the superoxide anion radical to generate stable acridine nitrone (23) and hydroperoxyl radical (19) via the benzhydryl 1,4-diradical 24. Indeed, the formation of benzhydryl radical upon photolysis of N-methylacridan (7) has been reported.12 The fact that 9-phenylacridan (5) is more active than acridan (4) provides further support for the mechanism outlined in Schemes 1 and 2. The hydroperoxyl radical 19 is known to be lethal to cells.8 In contrast, hydrogen abstraction from dihydrophenathrene nitroxyl radical 24 will yield the benzyl 1,2-diradical 25, which is less stable than the benzhydryl radical 21. In addition, the two unpaired electrons adjacent to each other in 25 induce strong electron repulsion, and any rearrangement of the diradical 25 to the corresponding 1,4-diradical will result in loss of aromaticity. Thus, the transition state for the formation of 25 and, hence, the formation of hydroperoxyl radical should be strongly disfavored.

Scheme 2.

The difference in activity between phenoxazine (8) and phenothiazine (9) could be attributed to the longer-lived N-centered radical (t1/2 = 1.0 s) compared to that of phenoxazine (t1/2 = 0.3 s).10 It was further shown that phenoxazine produced a neutral N-centered radical or radical cation, but not nitroxyl radical. In contrast, phenothiazine produced a mixture of nitroxyl and neutral N-centered radicals, confirming that nitroxyl radicals could cause cell death. The sharp differences in the activities among the tricyclic azepine series of compounds 10–12 can be explained by the mechanism outlined in Scheme 3. As in the case of dihydrophenanthrene, although the benzyl 1,4-diradical 27 is more stable than the 1,2-diradical 25, nevertheless, the rearrangement will still result in the loss of aromaticity. The photolysis of dibenzazepine 11 could result in the formation of stable azatropylium cation 29(7,26,27) and hydroperoxyl radical anion 19 via electron and hydrogen transfer to the oxygen. In the case of triazepine 12, the transition state leading to the formation of the cation 30 may not be possible due to the strong deactivating effect of the two sp2 nitrogens of the azo group. Except for diphenylamine and carbazole, the cell viability data of diarylamines parallels the activities of the previously reported sulfenamides7 derived from the corresponding diarylamines. The diarylamines in this work absorb in the UV-A/UV-B region. To be clinically useful, these diarylamines must not only absorb in the visible region but also display low systemic toxicity. Although anilines have been known to exhibit red cell and liver toxicity,28,29 interestingly, the diarylamines have been recently shown to play a beneficial role against oxidative stress.30

Scheme 3.

In this preliminary communication we have shown that the secondary diarylamino moiety could be a viable functional group for the design of suitable type 1 photosensitizers. We have demonstrated that the photolysis of diarylamines generates reactive species that destroy the cancer cells. The presence of the hydrogen atom on the nitrogen is a key requirement for activity. This observation is consistent with our previous work with sulfenamides7 and also with the mechanism outlined in Scheme 1, which supports the formation of nitrogen-centered radicals such as 16 as the initial reactive intermediate. The aminyl radical 16 itself or secondary ROS generated by the reaction of 16 with oxygen could cause cell death, but it remains to be established which of these reactive species is directly responsible for inducing cell death. Further work is in progress to enable the diarylamines to undergo photoexcitation in the visible region, to mitigate systemic toxicity, and to elucidate the precise mechanism of action of these type 1 photosensitizers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Richard Loomis and Dr. Gary Cantrell for insightful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

In vitro assay procedures and cell viability graphs of compounds 1–3, 6–10, 12, and 13a,b. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Nyst H. J.; Tan B. I.; Stewart F. A.; Balm A. J. M. Is Photodynamic Therapy a Good Alternative to Surgery and Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer?. Photodiagn. Photodyn Ther. 2009, 6, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney E.; Baker A.; Ahdout J.; Hanke C. W.; Moy R. L.; Kouba D. J. Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of Neoplasia, Inflammatory Disorders, and Photoaging. Dermatol. Surg. 2009, 35, 725–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. C. E.; Ortel B.; Hasan T.. Mechanisms of Photodynamic Therapy. In Photodynamic Therapy; Patrice T., Ed.; RSC: Cambridge, 2003; pp 19–57. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A. E.; Gallagher W. M.; Byrne A. T. Porphyrin and Non-porphyrin Photosensitizes in Oncology: Preclinical and Clinical Advances in Photodynamic Therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2009, 85, 1053–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmanto A. S.; Morgan P. E.; Hawkins C. L.; Davies M. J. Cellular Effects of Photogenerated Oxidants and Long-Lived, Reactive, Hydroperoxide Photoproducts. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1505–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A. A Review of progress in Clinical Photodynamic Therapy. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2005, 4, 283–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karwa A.; Poreddy A. R.; Asmelash B.; Lin T.-S.; Dorshow R. B.; Rajagopalan R. Type 1 Phototherapeutic Agents, Part I. Preparation and Cancer Cell Viability Studies of Novel Photolabile Sufenamides. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 828–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardman P.; Dennis M. F.; Everett S. A.; Patel K. B.; Stratford M. R. L.; Tracy M.. Radicals from One-electron Reduction of Nitro Compounds, Aromatic N-Oxides, and Quinones: The Kinetic Basis for Hypoxia-Selective, Bioreductive Drugs. In Free Radicals and Oxidative Stress: Environment, Drugs, and Food Additives; Rice-Evans C., Halliwell B., Gunt G. G., Eds.; Portland Press: London, 1995; pp–171–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S. M.; Wilson L.; Krishna C. M.; Leibman J.; DeGraff W.; Gamson J.; Samuni A.; Venzon D.; Mitchell J. B. Identification of Nitroxide Radioprotectors. Radiat. Res. 1992, 132, 87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T.-S.; Retsky J. ESR Studies of Photochemical Reactions of Diphenylamines, Phenothiazines and Phenoxazines. J. Phys. Chem. B 1986, 90, 2687–2689. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert B. C.; Chiu M. F.; Hanson P. Electron Spin Resonance of Some Heterocyclic Radicals Containing Elements of Group VI. J. Chem. Soc. [Sect. B]: Phys. Org. 1970, 9, 1700–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Rahn R.; Schroeder J.; Troe J.; Grellman K. H. Intensity-Dependent Ultraviolet Laser Flash Excitation of Diphenylamine in Methanol: A Two-Photon Ionization Mechansim Involving the Triplet State. J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 93, 7841–7856. [Google Scholar]

- Martin M.; Breheret E.; Tfibel F.; Lacourbas B. Two-Photon Stepwise Dissociation of Carbazole in Solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1980, 84, 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla D.; Rege de F.; Wan P.; Johnston L. J. Laser Flash Photolysis and Product Studies of the Photoionization of N-Methylacridan in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 10240–10246. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; McGimpsey W. G. One- and Two-Laser Photochemistry of Iminodibenzyl. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 9668–9672. [Google Scholar]

- Brede O.; Maroz A.; Hermann R.; Naumov S. Ionization of Cyclic Aromatic Amines by Free Electron Transfer: Products Are Governed by Molecule Flexibility. J. Phys. Chem. 2005, 109, 8081–8087-9672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola G.; Miolo G.; Vedaldi D.; Dall'Acqua F. In Vitro Studies of the Phototoxic Potential of the Antidepressant Drug Amitriptyline and Imipramine. Farmaco 2000, 55, 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta B.; Kar G. K.; Ray J. K. Direct Regioselective Phenylation of Acridine Derivatives with Phenyllithium. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 8641–8643. [Google Scholar]

- Charbit J. J.; Galy A. M.; Galy J. P.; Barbe J. Preparation of Some New N-Substituted 9,10-Dihydroacridine Derivatives. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1989, 34, 136–137. [Google Scholar]

- Allinger N. L.; Youngdale G. A. Aromatic and Pseudoaromatic Non-benzenoid Systems. III. The Synthesis of some Ten p-Electron Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R.; Rajagopalan R.; Schwarz J. Selective Functionalization of Doubly Coordinated Flexible Chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 2905–2907. [Google Scholar]

- Hopff H.; Gutenberg H. 2-Vinylthianthrene and Its Polymerization Products. Makromol. Chem. 1963, 60, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen E. G. Radical Addition Reactions of 5,5-Dimethyl-l-pyrroline-l-oxide. ESR Spin Trapping with a Cyclic Nitrone. J. Magn. Reson. 1973, 9, 510–512. [Google Scholar]

- Migita C. T.; Migita K. Spin Trapping of the Nitrogen Radicals. Chem. Lett. 2003, 32, 466–467. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. J.; Lin S. Q.; Shen S. Y.; Chen D. W.; Xu G. Z. Radical Mechanism in the Photoinduced Oxygen Transfer from Acridine N-Oxide to Cyclohexene. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A: Chem. 1989, 48, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cann M. C. Formation of Acridine from the reaction of Dibenz[b,f]azepine with Silver(I): Formation of an Aromatic Nitrenium Ion?. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 1112–1113. [Google Scholar]

- Bausch M. J.; Gostowski R. Homolytic and Heterolytic Bond Strengths. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 6260–6262. [Google Scholar]

- Eyer P. The Red Cell as a Sensitive Target for Activated Toxic Arylamines. Arch. Toxicol., Suppl. 1983, 6, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada A. Cytotoxicity of Aniline Derivatives. Igakkai Zasshi 1990, 99, 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Basto D.; Silva J. P.; Queiroz M. J.; Moreno A. J.; Coutinho O. P. Antioxidant Activity of Synthetic Diarylamiines: A Mitochondrial and Cellular Approach. Mitochondrion 2009, 9, 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.