Abstract

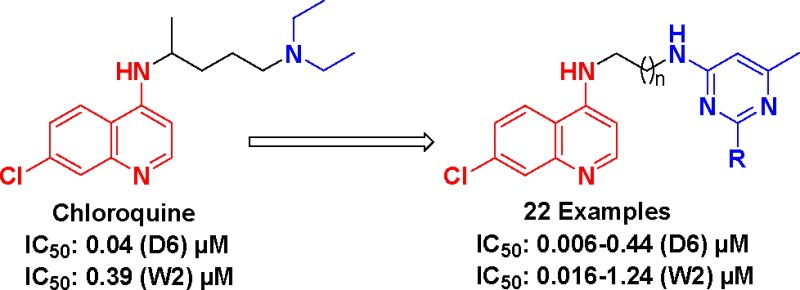

A class of hybrid molecules consisting of 4-aminoquinoline and pyrimidine were synthesized and tested for antimalarial activity against both chloroquine (CQ)-sensitive (D6) and chloroquine (CQ)-resistant (W2) strains of Plasmodium falciparum through an in vitro assay. Eleven hybrids showed better antimalarial activity against both CQ-sensitive and CQ-resistant strains of P. falciparum in comparison to standard drug CQ. Four molecules were more potent (7–8-fold) than CQ in D6 strain, and eight molecules were found to be 5–25-fold more active against resistant strain (W2). Several compounds did not show any cytotoxicity up to a high concentration (60 μM), others exhibited mild toxicities, but the selective index for the antimalarial activity was very high for most of these hybrids. Two compounds selected for in vivo evaluation have shown excellent activity (po) in a mouse model of Plasmodium berghei without any apparent toxicity. The X-ray crystal structure of one of the compounds was also determined.

Keywords: 4-aminoquinoline, pyrimidine, antimalarial

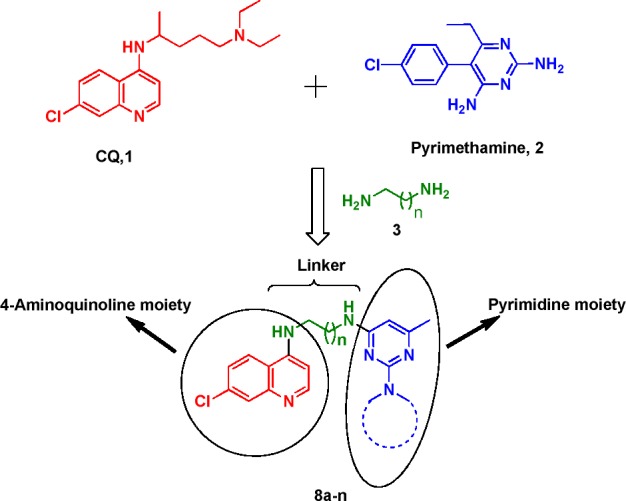

In terms of human deaths per year, malaria is the third most infectious disease after HIV and tuberculosis.1 According to the World malaria report 2011, there were 216 million cases of malaria in 106 endemic countries and territories in the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 225 million episodes of malaria occur annually with 0.7–1.0 million deaths a year, and over 85% of deaths are of children below the age of 5 years in sub-Saharan Africa.2Plasmodium falciparum is the most virulent species of the malaria parasite and is responsible for most of the malaria-related deaths.3,4 The 4-aminoquinoline class of therapeutics remains a frontline drug of choice for combating malaria even after several decades of drug development efforts.5 The success of this antimalarial pharmacophore is based on its excellent clinical efficacy, ease of administration, low toxicity, and cheap synthesis.5 These features make this pharmacophore so interesting that it is very difficult to abandon. However, a worldwide increase of P. falciparum-resistant strains6 has severely circumscribed the choice of traditionally used chloroquine (CQ, 1), while amodiaquine was abandoned due to its severe toxic effects (Figure 1). However, despite this global diffusion of resistance at an alarming speed, 4-aminoquinoline derivatives continue to be the most sought out antimalarial agents for chemical modification. To overcome the problem of drug resistance, combination therapy has been used with limited success,7 and recently, the concept of hybrid molecules has been introduced in an anticipation that these kind of molecules may overcome drug resistance problems.8−10 In hybrid molecules, two or more pharmacophores are linked together covalently, and it is believed that these compounds act by inhibiting simultaneously two conventional targets. This multiple target strategy led to the discovery of various hybrid molecules including 4-aminoquinoline-trioxane-,10 4-aminoquinoline-triazine-,11,12 4-aminoquinoline-isatin-,13 4-aminoquinoline-ferrocene-,14 and, more recently, 4-aminoquinoline-based mannich bases.15 It is important to mention here that some of these hybrid compounds have also entered into clinical trials.9

Figure 1.

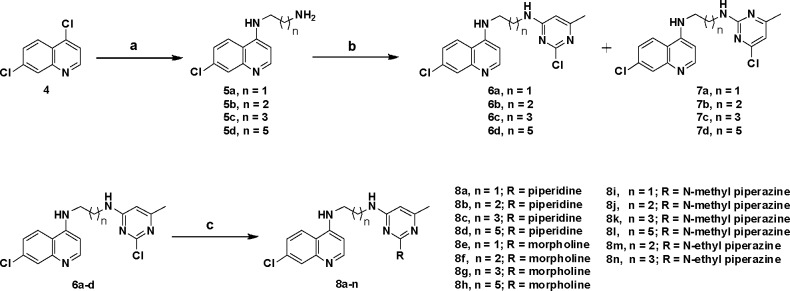

Synthesis of 4-aminoquinoline-pyrimidine hybrids under present investigation.

The pyrimidine-based compounds are well-known for their wide range of biological activity such as fungicidal,16 herbicidal,17 analgesic,18 anti-inflammatory,19 antitumor,20 and antimalarial21 activities apart from their role in the nucleic acid synthesis.22 The pyrimethamine (2), a pyrimidine analogue, has been used for the treatment of malaria with limited success.23

On the basis of these observations and in continuation of our efforts to develop new structurally diverse molecular scaffolds for the treatment of malaria,24−26 we proposed to link 4-aminoquinoline and pyrimidine entities together via flexible linear-chained diaminoalkane (3) linkers (Figure 1), so that the molecule has enough flexibility to fit in the binding site of the target, and as a result, this kind of hybrid molecules may show better antimalarial activity. It is important to mention here that Chauhan et al. reported the synthesis of 4-aminoquinoline-pyrimidine conjugates in which 4-aminoquinoline and pyrimidine moieties were linked through an aromatic ring,27 and some of these compounds have shown moderate activity.

The 4-aminoquinoline-pyrimidine conjugates were synthesized using a three-step procedure as outlined in Scheme 1.28 The commercially available starting material 4,7-dichloroquinoline (4) was reacted with an excess of aliphatic linear chain diaminoalkanes via a SNAr type of reaction in neat conditions as reported in the literature to afford substituted 4-aminoquinolines (5a–d) with free terminal amino groups in good to excellent yield.29 These intermediates (5a–d) on reaction with commercially available 2,4-dichloro-6-methyl-pyrimidine yielded two regioisomers viz. 6a–d in major and 7a–d in minor yield. The major regioisomers 6a–d were subjected to nucleophilic substitution with different cyclic secondary amines at an elevated temperature in DMF as the solvent to yield 4-aminoquinoline-pyrimidine conjugates (8a–n) in excellent yield. The crystal structure of one of the conjugate 8f was also determined.

Scheme 1.

The in vitro antimalarial activity of all of the conjugates was evaluated against both CQ-sensitive (D6 clone) and CQ-resistant (W2 clone) strains of P. falciparum, while mammalian cell cytotoxicity was determined against Vero, LLC-PK11, and HepG2 cells (Table 1) using the procedure as described earlier.30 Most of the compounds showed very promising antimalarial activity in the in vitro screening. Out of these, 11 compounds (8b,c, 8e,f, and 8h–n) have displayed better antimalarial activity (IC50 = 0.005–0.03 μM) against the CQ-sensitive strain, while 12 compounds (8b–f and 8h–n) have displayed better antimalarial activity (IC50 = 0.01–0.21 μM) against the CQ-resistant strains of P. falciparum, Four hybrids (8i, 8j, 8l, and 8m) showed 1.6–2.0-fold higher activity in comparison to pyrimethamine against both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant strains (D6 and W2) of P. falciparum, in contrast to pyrimethamine, which was inactive up to 19 μM concentration against W2 strain. Pyrimidine-based compounds N1-[6-methyl-2-(4-methyl-piperazin-1-yl)-pyrimidin-4-yl]-ethane-1,2-diamine and N-(7-chloro-quinolin-4-yl)-N′-[2-(4-ethyl-piperazin-1-yl)-6-methyl-pyrimidin-4-yl]-propane-1,3-diamine, an integral part of the most active compounds 8i and 8m showed appreciable activity against D6 strain (IC50 = 0.12 and 0.18 μM, respectively), while these compounds showed poor antimalarial activity (IC50 = 10 and 16 μM, respectively) against the drug-resistant (W2) strain. As evident from Table 1, these hybrids showed efficacy in the nanomolar range against both of the strains (D6 and W2), and it indicates an improved activity of the two molecules in the conjugate form as compared to the individual form.

Table 1. In Vitro Antimalarial Activity and Cytotoxicity of 4-Aminoquinoline-pyrimidine Hybridsa.

|

P. falciparum (D6 clone) |

P. falciparum (W2 clone) |

IC50 (μM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd no. | IC50 (μM)b | SI | IC50 (μM) | SI | VERO | LLC-PK11 | HepG2 |

| 6a | 0.16 ± 0.05 | >3.70 × 102 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | >1.20 × 102 | NC | NC | NC |

| 6b | 0.33 ± 0.02 | >1.84 × 102 | 0.70 ± 0.04 | >85 | NC | NC | NC |

| 6c | 0.12 ± 0.03 | >5.00 × 102 | 0.68 ± 0.01 | >88 | NC | NC | NC |

| 6d | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 74.3 | 0.54 ± 0.00 | 60.6 | 32.7 ± 1.8 | 15.8 ± 1.0 | 9.1 ± 0.2 |

| 7a | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 2.05 × 102 | 0.81 ± 0.10 | 53.1 | 43.0 ± 0.0 | 42.3 ± 0.7 | 43.0 ± 0.0 |

| 7b | 0.24 ± 0.03 | >2.50 × 102 | 1.17 ± 0.07 | >51.3 | NC | NC | NC |

| 7c | 0.17 ± 0.02 | >3.53 × 102 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | >94 | NC | NC | 46.4 ± 6.6 |

| 7d | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 3.53 × 102 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 85.2 | 49.4 ± 6.2 | 24.0 ± 0.6 | 8.1 ± 0.0 |

| 8a | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 8b | 0.02 ± 0.001 | >3.00 × 103 | 0.21 ± 0.003 | >2.85 × 102 | NC | NC | NC |

| 8c | 0.02 ± 0.002 | >3.00 × 103 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | >6.66 × 102 | NC | NC | NC |

| 8d | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 1.46 × 102 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 88 | 8.8 ± 0.5 | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 6.4 ± 0.3 |

| 8e | 0.02 ± 0.002 | >3.00 × 103 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | >4.44 × 102 | NC | NC | NC |

| 8f | 0.02 ± 0.00 | >3.00 × 103 | 0.05 ± 0.004 | >1.20 × 103 | NC | 35.7 ± 0.6 | 26.2 ± 4.8 |

| 8g | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 8h | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 5.03 × 102 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 1.07 × 102 | 15.1 ± 2.0 | 11.1 ± 1.3 | 6.4 ± 0.3 |

| 8i | 0.005 ± 0.001 | >1.20 × 104 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | >2.00 × 103 | NC | NC | NC |

| 8j | 0.007 ± 0.00 | >8.57 × 103 | 0.06 ± 0.002 | >1.00 × 103 | NC | 34.6 ± 0.6 | 26.7 ± 0.9 |

| 8k | 0.02 ± 0.001 | >3.00 × 103 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | >3.00 × 103 | NC | 34.6 ± 0.6 | 29.5 ± 2.3 |

| 8l | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 1.48 × 103 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 6.50 × 102 | 10.4 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.4 |

| 8m | 0.006 ± 0.00 | >1.00 × 104 | 0.06 ± 0.001 | >1.00 × 103 | NC | NC | NC |

| 8n | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 1.62 × 103 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | 1.62 × 103 | 32.4 ± 0.5 | 10.7 ± 0.2 | 15.4 ± 0.6 |

| CQ | 0.04 ± 0.004 | >1.50 × 103 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | >1.52 × 102 | NC | NC | NC |

| artemisinin | 0.01 ± 0.001 | >6.00 × 103 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | >6.00 × 103 | NC | NC | NC |

| pyrimethamine | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 1.82 × 103 | NA | 18.2 ± 0.1 | NT | NT | |

| doxorubicin | 8.6 ± 0.4 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | ||||

IC50, the concentration that causes 50% growth inhibition; SI, selectivity index (IC50 for cytotoxicity to Vero cells/IC50 for antimalarial activity); and ND, not determined.

Average values of two independent experiments ± standard deviations (SDs). NA, not active up to highest tested concentration (19 μM). NC, no cytotoxicity up to 60 μM; NT, not tested; Vero, monkey kidney fibroblasts; LLC-PK11, pig kidney epithelial cells; and HepG2, human hepatoma cells.

The selectivity index of antimalarial activity (calculated as a ratio of IC50 for cytotoxicity to Vero cells and IC50 for antimalarial activity) was very high for most of these compounds as compared to standard drug CQ. The activity of compounds 8i, 8j, 8l, and 8m was 6–8-fold higher than CQ and 2-fold higher than artemisinin in CQ-sensitive strain, and the activity of compounds 8c, 8f, and 8i–n was 6–26-fold higher than CQ-resistant strains, while compounds 8l and 8n showed comparable activity as artemisinin in the CQ-resistant strain, revealing their strong potency. The comparison of antimalarial activity of 6a–d with 8a–n clearly showed that substitution of Cl from compounds 6a–d (IC50 = 0.12–0.44 μM for CQ-sensitive and 0.50–0.70 μM for CQ-resistant) with secondary amines (8b–f and 8h–n, IC50 = 0.005–0.06 μM for CQ-sensitive and 0.02–0.21 μM for CQ-resistant) improves the antimalarial activity of these compounds. The comparison of antimalarial activity of two groups of regioisomers 6a–d (IC50 = 0.12–0.44 μM for CQ-sensitive and 0.50–0.70 μM for CQ-resistant) and 7a–d (IC50 = 0.14–0.24 μM for CQ-sensitive and 0.58–1.17 μM for CQ-resistant) clearly indicates that both the regioisomers displayed more or less similar potency against both of the strains of P. falciparum. These results indicate that the point of attachment of the spacer to the pyrimidine nucleus may not have a great impact on activity profile. For a particular amino-substituted 4-aminoquinoline-pyrimidine hybrids (8a–d or 8e–h or 8i–l), a structure–activity relationship (SAR) study demonstrated no obvious trend of activity with increasing or decreasing carbon spacers from C2 to C6, but changing the amino groups for a particular C2 (8e and 8i), C3 (8b, 8f, 8j, and 8m), C4 (8c, 8k, and 8n), or C6 (8d, 8h, and 8l) spacer changes the activity significantly in a decreasing order of 4-ethyl piperazine > 4-methyl piperazine > morpholine > piperidine.

Among the most active compounds (8b–f and 8h–n), 8d, 8h, and 8l showed toxicity to all of the three cell lines (VERO, LLC-PK–11, and HepG2), but their selectivity index of antimalarial activity was considerably high (Table 1). In general, the cytotoxicity of the most of the conjugates appeared at much higher concentrations than the concentrations responsible for their antimalarial activity. Some of the hybrids were not cytotoxic at all up to the highest tested concentration of 60 μM, indicating their high selectivity index of antimalarial activity versus cytotoxicity to mammalian cells.

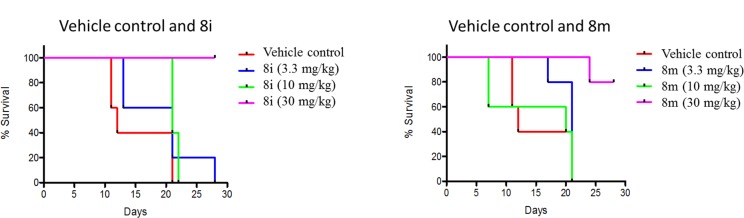

Two of the potent molecules 8i and 8m were selected for further in vivo evaluation. In vivo antimalarial activity was determined through oral route of administration in P. berghei–mouse malaria model. The compounds were administered to the P. berghei-infected mice, through oral gavage, once daily on days 0, 1, and 2 days postinfection and monitored for apparent signs of toxicity, parasitemia, and survival until day 28 postinfection (Table 2). Both compounds exhibited excellent in vivo antimalarial activity without any toxicity. The compound 8i was better active as compared to 8m and CQ, the control used in this study. Treatment with compound 8i, at three doses of 30 mg/kg, produced almost complete suppression of parasitemia and cured 80% of the treated mice, as compared to only 20% cured by 8m and no cure by CQ (Figure 2). Although CQ is a highly tolerated drug and produces cure in mice at higher doses, in the present in vivo study, the dose was selected to get the comparative results with the test compounds. The mechanistic studies involving inhibition of hemozoin formation (a potential target of CQ) and dihydrofolate reductase (a target for the pyrimethamine) and structural modification of the lead molecules are in progress, and results will be published in due course of time.

Table 2. In Vivo Antimalarial Activity of Selected 4-Aminoquinoline-pyrimidine Hybrids in the P. berghei–Mouse Malaria Model.

| % suppression

in parasitemiaa |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment (po) | dose (mg/kg × no. of days postinfection) | day 5 | day 7 | survivalb | MSTc | cured |

| vehicle | NA × 4 | 0/5 | 15.2 | 0/5 | ||

| CQ | 100 × 3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 5/5 | 28 | 0/5 |

| 8i | 3.3 × 3 | 23.5 | 35.2 | 1/5 | 19.2 | 0/5 |

| 8i | 10 × 3 | 97.0 | 2.0 | 0/5 | 21.4 | 0/5 |

| 8i | 30 × 3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 5/5 | 28 | 4/5 |

| 8m | 3.3 × 3 | 20.1 | 19.1 | 0/5 | 20.2 | 0/5 |

| 8m | 10 × 3 | 73.9 | 27.1 | 0/5 | 15.2 | 0/5 |

| 8m | 30 × 3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 4/5 | 27.2 | 1/5 |

The % suppression in parasitemia is calculated by considering the mean parasitemia in the vehicle control as 100%. Parasitemia suppression <80% is considered as nonsignificant.

Number of animals that survived on day 28/total animals in the group (the day of the death postinfection).

MST, mean survival time (days).

Number of mice without parasitemia (cured) until day 28 postinfection.

Figure 2.

Dose regime of compounds 8i and 8m.

In summary, a series of 4-aminoquinoline-pyrimidine hybrids were prepared in an attempt to search for more potent molecule that can be effective against both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant strains of P. falciparum. The in vitro antimalarial activity profile of these compounds indicates that in comparison to CQ, 11 hybrids (8b, 8c, 8e, 8f, 8h–n) showed better antimalarial activity, while in comparison to pyrimethamine, four hybrids (8i, 8j, 8l, and 8m) showed better activity against both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant (D6 and W2) of P. falciparum. Out of these hybrids, 8i, 8j, 8l, and 8m were 6–8 times more potent than CQ and 1.6–2.0 times more potent than pyrimethamine and artemisinin against the D6 strain. In the W2 strain, they were 6–26 times more potent than CQ and equally potent as artemisinin. In contrast, pyrimethamine was inactive against the drug-resistant strain. The pyrimethamine- and pyrimidine-based compounds are either not active or weakly active against W2 strain, while these hybrids showed nanomolar range activity against both the strains, which confirms and indicates the synergistic effect of covalent binding of pyrimidine to aminoquinolines.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to USIC-CIF, University of Delhi, for analytical data. We are thankful to Dr. Rajeev Gupta and Afsar Ali for solving the X-ray crystal structure. John Trott and Rajnish Sahu are acknowledged for technical support in the biological activity evaluation.

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic method and characterization of compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

D.S.R. conceived and designed the work; S.M. and U.C.R. performed the synthesis and characterization of the compounds; and S.I.K. and B.L.T. are responsible for evaluation of in vitro and in vivo antimalarial activity.

D.S.R. thanks Department of Science and Technology (SR/S1/OC-08/2008), New Delhi, India, and University of Delhi, Delhi, India, for financial support. S.M. is thankful to CSIR and U.C.R. is thankful to UGC, India, for the award of senior and junior research fellowship, respectively. S.I.K. is thankful to U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service Specific Cooperative Agreement No. 58-6408-2-0009, for partial support of this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Beckera K.; Hua Y.; Biller-Andorno N. Infectious diseases: A global challenge. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 296, 179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Malaria Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley R. J. Medical need, scientific opportunity and the drive for antimalarial drugs. Nature 2002, 415, 686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N.; Singh R.; Rawat D. S. Tetraoxanes: Synthetic and medicinal chemistry perspective. Med. Res. Rev. 2012, 32, 581–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouznetsov V. V.; Gomez-Barrio A. Recent developments in the design and synthesis of hybrid molecules based on aminoquinoline ring and their antiplasmodial evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3091–3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp A. M.; Norsten F.; Yi P.; Das D.; Phyo A. P.; Tarning J.; Lwin K. M.; Ariey F.; Hanpithithakpong W.; Lee S. J.; Ringwald P.; Silamut K.; Imwong M.; Chotivanich K.; Lim P.; Herdman T.; An S. S.; Yeung S.; Singhasivanon P.; Day N. P. J.; Lindegardh N.; Socheat D.; White N. J. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 455–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloland P. B.; Ettling M.; Meek S. Combination therapy for malaria in Africa: hype or hope?. Bull. World Health Org. 2000, 78, 1378–1388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert A.; Dechy-Cabaret O.; Cazelles J.; Meunier B. From mechanistic studies on artemisinin derivatives to new modular antimalarial drugs. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier B. Hybrid molecules with a dual mode of action: Dream or reality?. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechy-Cabaret O.; Benoit-Vical F.; Robert A.; Meunier B. Preparation and antimalarial activities of trioxaquines, new modular molecules with a trioxane skeleton linked to a 4-aminoquinoline. ChemBioChem 2000, 1, 281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar S.; Khan S. I.; Rawat D. S. Synthesis, antimalarial activity and cytotoxicity of 4-aminoquinoline-triazine conjugates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar S.; Khan S. I.; Rawat D. S. Synthesis of 4-aminoquinoline-1,2,3-triazole and 4-aminoquinoline-1,2,3-triazole-1,3,5-triazine hybrids as potential antimalarial agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2011, 78, 124–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiyanzu I.; Clarkson C.; Smith P. J.; Lehman J.; Gut J.; Rosenthal P. J.; Chibale K. Design, synthesis and anti-plasmodial evaluation in vitro of new 4-aminoquinoline isatin derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 3249–3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biot C.; Glorian G.; Maciejewski L. A.; Brocard J. S. Synthesis and antimalarial activity in vitro and in vivo of a new Ferrocene-Chloroquine analogue. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 3715–3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel N. I.; Chavain N.; Wang Y.; Friebolin W.; Maes L.; Pradines B.; Lanzer M.; Yardley V.; Brun R.; Herold-Mende C.; Biot C.; Toth K.; Davioud-Charvet E. Antimalarial versus cytotoxic properties of dual drugs derived from 4-aminoquinolines and mannich bases: Interaction with DNA. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3214–3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves S. L.; Pilkington B. L.; Russell S. E.; Worthington P. A. The synthesis of substituted pyridylpyrimidine fungicides using palladiumcatalysed cross-coupling reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. X.; Luo Y. P.; Xi Z.; Niu C. W.; He Y. Z.; Yang G. F. Design and syntheses of novel phthalazin-1(2H)-one derivatives as acetohydroxyacid synthase inhibitors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 9135–9139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnier G.; Canevar L.; Le R. J.; Douarec J. C.; Halstop S.; Daussy J. Triphenylpropylpiperazine derivatives as new potent analgetic substances. J. Med. Chem. 1972, 15, 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondhi S. M.; Singh N.; Johar M.; Kumar A. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities evaluation of some mono, bi and tricyclic pyrimidine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 6158–6166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos M. G.; John R. M.; Charles D. Nucleoside analogues and nucleobases in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2002, 3, 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn D. C.; Nijjar A.; Celatka C. A.; Mazitschek R.; Cortese J. F.; Tyndall E.; Liu H.; Fitzgerald M. M.; ÒShea T. J.; Danthi S.; Clardy J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 228–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qingyun R.; Xiaosong T.; Hongwu H. Efficient synthesis of fused pyrimidine derivatives with biological activity via aza-wittig reaction. Curr. Org. Synth. 2011, 8, 752–763. [Google Scholar]

- Delfino R. T.; Santos-Filho O. A.; Figueroa-Villar J. D. Type 2 antifolates in the chemotherapy of falciparum malaria. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2002, 13, 727–741. [Google Scholar]

- Atheaya H.; Khan S. I.; Mamgain R.; Rawat D. S. Synthesis, thermal stability, antimalarial activity of symmetrically and asymmetrically substituted tetraoxanes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 1446–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N.; Khan S. I.; Beena; Rajalakshmi G.; Kumaradhas P.; Rawat D. S. Synthesis, antimalarial activity and cytotoxicity of substituted 3,6-diphenyl-[1,2,4,5]tetraoxanes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 5632–5638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N.; Khan S. I.; Atheaya H.; Mamgain R.; Rawat D. S. Iodine-catalyzed one-pot synthesis and antimalarial activity evaluation of symmetrically and asymmetrically substituted 3,6-diphenyl[1,2,4,5]tetraoxanes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2816–2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M.; Chaturvedi V.; Manju Y. K.; Bhatnagar S.; Srivastava K.; Puri S. K.; Chauhan P. M. S. Substituted quinolinyl chalcones and quinolinyl pyrimiines as a new class of anti-infective agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 2081–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat D. S.; Manohar S.; Rajesh U. C.. Aminoquinoline based hybrids and uses thereof. Indian Patent Application No. 661/DEL/2012.

- Natarajan J. K.; Alumasa J. N.; Yearick K.; Ekoue-Kovi K. A.; Casabianca L. B.; de Dios A. C.; Wolf C.; Roepe P. D. 4-N-, 4-S-, and 4-O-Chloroquine analogues: Influence of side chain length and quinolyl nitrogen pka on activity vs chloroquine resistant malaria. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 3466–3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M.; Khan S. I.; Tekwani B. L.; Jacob M. R.; Singh S.; Singh P. P.; Jain R. Synthesis, antimalarial, antileishmanial, and antimicrobial activities of some 8-quinolinamine analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 4458–4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.