Abstract

This paper examines the differences in drug offers and recent drug use between Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth residing in rural communities, and the relationship between drug offers and drug use of Hawaiian youth in these communities. Two hundred forty nine youth (194 Hawaiian youth) from 7 different middle or intermediate schools completed a survey focused on the social context of drug offers. Hawaiian youth in the study received significantly more offers from peers and family, and had significantly higher rates of recent alcohol and marijuana use, compared with non-Hawaiian youth. Logistic regression analysis indicated that the social context differentially influenced drug use of Hawaiian youth, with family drug offers and context influencing overall drug use and the use of the widest variety of substances. Implications for prevention practices are discussed.

Keywords: Culture, Drug offers, Drug use, Hawaiian, Youth

Research has indicated that present-day Native Hawaiians have suffered far more from socioeconomic stress (Hawai‘i Department of Health, 2005) and health disparities (Liu, Blaisdell, & Aitaoto, 2008; Tsark, Blaisdell, & Aluli, 1998) compared with their non-Hawaiian counterparts. At particular risk are Hawaiians who reside in rural communities in Hawai‘i (i.e., communities predominantly on islands other than O‘ahu), as they have been shown to have a higher prevalence of physical and mental illness and substance abuse than those from urban areas (Waitzfelder, Engel, & Gilbert, 1998). Despite these problems, there have been relatively few studies focused on this population (Mokuau, Garlock-Tuiali‘i, & Lee, 2008), creating a large gap in the health-related research literature for Indigenous and Pacific peoples. The etiology, prevention, and treatment of drug use are among the many needed research areas for this population (Rehuher, Hiramatsu, & Helm, 2008).

The purposes of this study are to examine the differences in drug use between Hawaiian and Non-Hawaiian middle school students in rural communities, and to explore the relationship between drug offers and drug use of Native Hawaiian youth in these communities. A recently developed survey called the Hawaiian Youth Drug Offers Survey (Okamoto, Helm, Giroux, Edwards, & Kulis, 2010) was used to predict overall drug use and the use of alcohol, cigarette, marijuana, and “hard drugs” for Hawaiian youth. The purpose of this process was to identify the most salient environmental factors that influence drug use for these youth. The findings from this study have implications for culturallytailored prevention programs for Hawaiian youth in rural communities, as well as for other Pacific Islander and Indigenous youth populations.

Drug Use Epidemiology of Native Hawaiian Youth

Several epidemiological studies have indicated that Native Hawaiian youth have an early initiation and high rates of drug use, and suffer adverse psychosocial and behavioral consequences as a result of their use. Compared with various ethnic groups, Native Hawaiian youth have some of the highest alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use rates (Glanz, Maskarinec, & Carlin, 2005; Kim, Ziedonis, & Chen, 2007; Lai & Saka, 2005; Makini et al., 2001; Mayeda, Hishinuma, Nishimura, Garcia-Santiago, & Mark, 2006; Wong, Klingle, & Price, 2004). Data also suggest an increased risk of substance abuse for middle-school aged Native Hawaiian youth as they enter high school. Using a large epidemiological data set (N = 23,972), Wong et al. found that 80% of Native Hawaiian youth had tried alcohol by the 10th grade. They also found that these youth had the highest percentage of lifetime cigarette (64%) and marijuana (52%) use compared with other ethnocultural groups in Hawai‘i. Further, Mayeda et al. found that rates of marijuana and alcohol use were significantly higher for Native Hawaiian girls than boys, pointing to gender differences in the risk for drug use within this population.

In terms of drug use onset, Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano, Goebert, and Nishimura (2004) found that a higher proportion of these youth initiated alcohol use by age 12 compared with Caucasian and other Asian Pacific Islander youth. Using statewide data from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey, Lai and Saka (2005) compared drug use initiation between Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth. Compared with non-Hawaiian youth, they found that a higher percentage of Native Hawaiian youth smoked their first cigarette (9.7 versus 5.9), drank their first sip of alcohol (20.4 versus 14.1), and tried marijuana (5.9 versus 2.8) before age 11.

Substance use has been linked with various psychosocial and behavioral consequences for Hawaiian youth. For example, it has been related to unsafe sexual practices (Ramisetty-Mikler et al., 2004), suicidal behavior (Else, Andrade, & Nahulu, 2007; Yuen, Nahulu, Hishinuma, & Miyamoto, 2000), poorer academic achievement (Hishinuma et al., 2006), and increases in school absences, suspensions, and infractions (Hishinuma et al., 2006) with this youth population. Further, compared with other ethnic groups, Wong et al. (2004) found that Hawaiian youth reported the highest need for drug and alcohol treatment, particularly treatment related to alcohol and marijuana use. Drug and alcohol treatment needs were found to be particularly high within rural Hawaiian communities (Withy, Andaya, Mikami, & Yamada, 2007). In sum, research has clearly indicated that substance use is a problem for Hawaiian youth. While the existing epidemiological literature has indicated the prevalence, gender differences, and adverse consequences of substance use for Hawaiian youth, there have been fewer studies focused on the etiology of drug use for these youth.

The Social Context of Drug Offers and Drug Use for Native Youth Populations

Over the past decade, several studies have focused on the social context of drug offers and drug use for Native youth populations. Much of this literature has focused on the influence of various offerer subgroups (e.g., peers and family) on the drug-using behaviors of these youth (e.g., Alexander, Allen, Crawford, & McCormick, 1999; Helm et al., 2008; Kulis, Okamoto, Dixon-Rayle, & Sen, 2006; Waller, Okamoto, Miles, & Hurdle, 2003). The influence of the family context on drug use has been described as a unique aspect of Native youth. For example, Waller et al. and Hurdle, Okamoto, and Miles (2003) used qualitative methods to describe how same-generation family members of American Indian youth, such as cousins or siblings, interacted with each other in multiple settings (e.g., home, school, and community). Waller et al. argued that the closeness and intensity of interactions across these different social contexts functioned to intensify both risk and protection related to drug use of these youth. Expanding upon these findings, Kulis et al. found that drug offers from parents predicted alcohol and cigarette use, while offers from cousins predicted marijuana use of Southwestern American Indian youth. Similar findings have been reported for Native Hawaiian youth. Based on a large multi-island sample in Hawai‘i, Goebert et al. (2000) found that overall recent family support (defined as feelings and experiences related to emotional support and reliance on family relationships within the past 6 months) led to a twofold decrease in the risk for substance abuse of Native Hawaiian youth, while Makini et al. (2001) found that overall recent family support was associated with fewer episodes of binge drinking for these youth.

Finally, some research has found gender differences in the social context of drug use for Native youth (Dixon Rayle et al., 2006; Okamoto, Kulis, Helm, Edwards, & Giroux, 2010). These studies found that both American Indian and Native Hawaiian girls were exposed significantly more to drug offer situations from various subgroups (e.g., cousins, peers, and adult family members), compared with their male counterparts. Further, girls in these studies also found it more difficult to refuse drugs in the majority of these situations. Aside from a few studies, there has been a lack of research focused on the social context of drug use for Hawaiian youth, thereby creating a lack of understanding of the causal environmental factors related to drug use of these youth.

Relevance of the Study

In recent years, there has been a national priority in understanding health disparities of ethnic minority populations, including differences in drug abuse and addiction between minority and non-minority populations (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2009). Along this vein, the present study focused on differences in early drug use between Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth, which have implications for informing the research literatures of both Indigenous and Pacific Islander youth. Research on Indigenous youth populations has indicated higher substance use rates compared with non-Indigenous youth (Wallace et al., 2003), while specific information on the substance use of Pacific Islander youth is largely unknown since the population is typically collapsed with Asian American youth in research studies (Liu et al., 2008; Mokuau et al., 2008). Combining Asian American and Pacific Islander populations in drug research has been described as problematic, since lower rates of drug use for Asian Americans often diminish the higher rates of Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians (Mayeda et al., 2006). Further, while other studies have operationalized and systematically examined the social contexts of drug offers and their relationship to drug use of indigenous youth populations (e.g., Kulis et al., 2006), this study is one of the first to examine this relationship specifically with Native Hawaiian youth. By understanding the unique social contexts related to drug use for Native Hawaiian youth, prevention interventions can focus on equipping these youth with relevant and realistic skills to manage and resist demands to use drugs and alcohol.

Research Questions

This study focused on two primary research questions and one secondary research question:

What are the differences in drug offers and recent drug use between Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth residing in rural communities?

- What is the relationship between drug offers and drug use for rural Native Hawaiian youth?

-

2aDo these offers have differential effects on drug use based on gender?

-

2a

Method

Participants and Procedures

Active parental consent was required for all students participating in the study. Three hundred and four students from 7 different middle or intermediate schools on the Island of Hawai‘i were offered to participate in the study and returned parental consent forms prior to survey administration. Thirty students (10%) received parental consent to participate in the study, but were absent on the day of survey administration in their respective schools. Twenty five students (8%) returned parental consent forms in which parents refused to allow their child to participate in the study. Subsequently, 249 youth (82% of those offered to participate in the study) completed the HYDOS. Schools participating in the survey were geographically focused within two of the three school complex areas in the Department of Education on the Island of Hawai‘i, and comprised 88% of the public middle or intermediate schools within the two complexes, and 47% of all public middle or intermediate schools on the island. Consistent with rural definitions from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Hawai‘i Rural Health Association (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2009; Withy et al., 2007), the schools also were located in areas with populations of less than 50,000. One hundred ninety four of the youth either self–identified or were documented in school records as “Hawaiian/Part Hawaiian,” while fifty-five of the youth identified as an ethnicity other than “Hawaiian/Part Hawaiian.” Of the latter youth, the majority identified as Filipino (44%), followed by Other Pacific Islander (15%), White (13%), Hispanic/Latino/Spanish (9%), Japanese (7%), Portuguese (7%), Chinese (4%), and Samoan (2%). In terms of grade level, the majority of youth were in 7th grade (47%), followed by 8th grade (27%) and 6th grade (25%). Seventy-one percent of all participating youth received free or reduced cost lunch through the federally-subsidized school lunch program for low income families. This was higher than the mean percentage for all schools participating in the study (M = 58%, SD = 10.3; Accountability Resource Center Hawai‘i, 2007)

Consistent with models of school-community-university partnerships in youth research (e.g., Spoth, 2007), youth were recruited for the study in collaboration with school-based research liaisons. These were school staff members, such as school counselors or health teachers, who were responsible for promoting and describing the study, distributing and collecting parental permission forms, and identifying space within their respective schools for survey administration. Liaisons were asked to focus their recruitment efforts on Hawaiian or Part Hawaiian youth in their respective schools. Youth who returned signed parental permission forms on or prior to the day of the survey administration were given youth assent forms to complete. All parts of the survey were read aloud to students to aid in the comprehension of the survey items. This may have also had the secondary outcome of mitigating respondent fatigue. All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Hawai‘i Pacific University, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, and the State of Hawai‘i Department of Education.

Measurement

Instrument

The Hawaiian Youth Drug Offers Survey (HYDOS) is comprised of 62 items which are intended to measure the frequency of exposure to offers for alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs and the perceived difficulty in dealing with these offers (Okamoto, Helm, et al., 2010). Using culturally “grounded” test development methods (Okamoto, Helm, et al., 2010), the survey originated from a series of gender-specific focus groups of Hawaiian youth (N = 47) on the Island of Hawai‘i. Focus group participants were asked to provide in-depth descriptions of situations where drugs or alcohol were offered to them, including details related to drug offerers, other individuals who were present during the offer situation, and location(s) and time(s) of the day where and when the offers occurred. Sixty-two short descriptions of drug offer scenarios were extracted from the focus group transcripts (see Table 1 for examples of these scenarios). They were organized such that survey participants could respond to each of them using two different Likert scales—(1) a frequency scale, which asked participants “How often have you been in a situation like this?” (0 = “Never”, 1 = “Once”, 2 = “2-3 times”, 3 = “4-10 times”, and 4 = “More than 10 times”) and (2) a difficulty scale, which asked participants “How difficult would it be for you to refuse drugs in this situation?” (0 = “Very Easy”, 1 = “Easy”, 2 = “Neither easy nor difficult”, 3 = “Difficult”, and 4 = “Very Difficult”).

Table 1.

The Hawaiian Youth Drug Offers Survey (Okamoto, Helm, et al., 2010)*

| Subscale 1: Peer Pressure (α = .93, Factor Loadings = 0.581 – 0.809) |

| There are two girls in your grade who are kind of tida and mean, and they use drugs. They try to encourage everyone to use. One day, they are in the bathroom making graffiti on the walls and smoking pakalolo. You walk in to use the bathroom, and they offer you some, but more like bully-tease you into trying. |

| Your friends bring Bacardi to school and mix it with juice. They are drinking it on campus during recess. They offer you some. |

| One of your friends uses drugs, but you haven't tried any yet. He/She tells you to try some weed, or you're a “chicken.” |

| On your school bus there are kids who bring beer in a soda can so it is not so obvious. They drink beer on the bus to and from school. One day, they ask you if you'd like to hang out with them. |

| You go to a community dance for kids. Some people are hanging out in the parking area drinking and using drugs. Your friend says to you, “Let's see what's going on in the parking lot.” |

| You go down to the beach where you see some of your friends, who happen to be smoking pakalolo. They notice you, and motion at you to join them. |

| During summer break, your friends invite you to go to the park with them. After a while, you end up going to someone's house, where your friends ask you if you want to smoke weed with them. |

| One of your classmates always hangs around with this group of older kids and they smoke weed every day. One day, your classmate asks you if you'd like to eat lunch with them. |

| Your friend's parents are away, so your friend has a party in the house. Some kids at the party brought “hards”, and are pouring shots for everyone. They pass one to you. |

|

Subscale 2: Family Offers and Context (α = .90, Factor Loadings = 0.452 – 0.821) |

| You have just left the movie theatre with two of your cousins. It is late in the evening and most of the stores around the theatre have closed. One of your cousins asks you if you'd like to smoke some weed. |

| Your older brother enters your bedroom, closes the door, and asks you if you'd like to smoke some weed. |

| You are at home having dinner with your family. Your parents are drinking beer with dinner, and your mom offers you some. |

| Your dad, uncles, papa, and dad's friends are making pulehu in the yard, and you are with them. Your mom is inside the house. They are drinking a lot of beer, probably already drunk. Your dad offers you a beer. |

| Your cousin who is in high school smokes cigarettes. He tells you, “smoking makes you look cool,” and then offers you one. |

| You're playing cards with you father. He's drinking a beer, and asks you if you'd like a sip. |

| You're camping with your ‘ohana, and your father and uncles are drinking beer by the fire. Your father turns to your uncle and, gesturing to you, says, “Go ahead and give him one.” |

| You're at the park with your older cousin. He takes out a pipe full of ice and says, “Try this.” |

| You're at a New Year's Eve Party with your ‘ohana, and your auntie's boyfriend offers you some of his beer. |

|

Subscale 3: Unanticipated Drug Offers (α = .91, Factor Loadings = 0.506 – 0.876) |

| Your best friend offers you marijuana. You don't know what might happen to your friendship if you say “no”. |

| You're at the mall with someone you just started dating. He/She pulls out a pipe, and asks you if you'd like to smoke some “ice.” |

| A group of high school boys are hanging out in the school parking lot after school, smoking weed. As you walk by them on the way to the bus, one of them says to you, “Hey, come over here.” |

| You're at the community recreational center after school. While in the locker room your best friend takes out some marijuana from his pocket and says “want some?” |

| Your older cousin is walking with you to the mall. He takes out some marijuana and says “don't tell my parents. You like some?” |

| You pass by some classmates before school who are standing in front of the cafeteria. One of them pulls out a container and says, “You like some weed?” |

Responses to items ranged from 0 = “Never”, 1 = “Once”, 2 = “2-3 times”, 3 = “4-10 times”, to 4 = “More than 10 times”

Measures

Dependent variables were youth reports of recent drug use, which were measured by how often, in the past 4 weeks, the respondent a) drank alcohol, b) smoked cigarettes, c) smoked marijuana, d) used “ice” (crystalmethamphetamine) and e) used other “hard drugs” (i.e., crack, cocaine, speed, crank, ecstasy, and/or sniffing glue or paint). Alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use were measured separately because they were described as drugs of choice for Hawaiian youth in prior research on the Island of Hawai‘i (Okamoto, Helm, Po‘a-Kekuawela, Chin, & Nebre, 2009; Okamoto, Helm, et al., 2010). “Ice” was measured separately from other “hard drugs” based on the described abuse and trafficking of the former drug on the Island of Hawai‘i (Affonso, Shibuya, & Frueh, 2007). An aggregated use of the five substances was also included as a dependent variable. Responses were organized on a five-point Likert scale (0 = “Never”, 1 = “Once”, 2 = “A few times”, 3 = “Once a week”, and 4 = “Almost every day”). The main independent variables were derived empirically through test development and validation procedures (Okamoto, Helm, et al., 2010). Respondents reported the frequency of encountering a variety of specific scenarios where drugs were offered or available to them. Exploratory factor analysis of the HYDOS items from the Hawaiian subsample (n = 194) indicated the presence of 3 factors accounting for 63% of the variance—(1) Peer Pressure (9 items), (2) Family Offers and Context (9 items), and (3) Unanticipated Drug Offers (6 items; see Table 1). “Peer Pressure” was comprised of offers in which peers or friends exerted substantial pressure to use drugs. “Family Offers and Context” consisted of situations where offers occurred in the presence of parents, cousins, aunts, or uncles. “Unanticipated Drug Offers” consisted of awkward and/or unpredicted drug offer situations. Offerers in these situations were not familiar to the respondent (e.g., someone “you just started dating”), or may have been withholding their drug use from the respondent (e.g., a cousin who asks the respondent “not to tell my parents” about smoking marijuana). Consistent with past test development research with Native youth populations (e.g., Okamoto, LeCroy, Dustman, Hohmann-Marriott, & Kulis, 2004), the factor structure was organized primarily around the presence of different offerer subgroups (e.g., family members, peers and friends), rather than by the presence of specific substances (e.g., marijuana, alcohol). Supporting the stability of the factor structure, items within each factor had consistently high communality estimates (.776-.983), and the overall structure reflected a high overdetermination of factors (6-9 items per factor with high factor loadings, see Table 1). Individual items with factor loadings of 0.45 or greater were retained for inclusion in each factor, except in the case of crossloaded items (i.e., those which loaded on two or more factors), which were not included in the factor structure. Further, internal consistency of the three HYDOS subscales was high (.90-.93; see Table 1). See Okamoto, Helm, et al. (2010) for a detailed description of the survey.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics, t-tests, and chi-square analyses were conducted to examine the differences in drug offers and drug use between Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth. Multivariate analyses were conducted with the Hawaiian subsample to examine the within group differences in the relationship between drug offers and drug use. More specifically, logistic regression analyses were used to explore the influence of peer pressure, family drug offers and context, and unanticipated drug offers on drug use, controlling for several demographic variables (i.e., age, SES, family structure, and gender). Several models also were created for comparative purposes using the full sample, with ethnicity (Hawaiian/non-Hawaiian) and/or interactions between ethnicity and each of the three HYDOS subscales as additional predictors. Because the outcomes were skewed toward infrequent or no use, logistic, rather than ordinary least squares regression was used to estimate better fitting models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and statistical tests of differences between the Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth are reported in Table 2. For the dependent variable outcomes and the three HYDOS subscales, both mean scores and the percentage of non-zero responses (i.e., those reporting any level of use of the substance and those encountering at least one of the drug offer scenarios) are presented. The percentage of non-zero responses functions as a proxy for exposure to drugs and drug offers in this study. In terms of recent drug use (i.e., within the past 4 weeks), the mean for both Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth ranged between 0 (indicating no use) and 1 (indicating use one time). Compared with non-Hawaiian youth, Hawaiian youth had significantly higher mean scores for the use of alcohol, t(162) = 3.85, p < .001, marijuana, t(121) = 2.14, p < .05, and of any substance, t(105) = 2.44, p < .05. Similarly, Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian respondents differed significantly in reporting any recent use of alcohol (31.6% versus 21.7%), χ2 (1, N = 245) = 7.63, p < .01, marijuana (14.5% versus 3.6%), χ2 (1, N = 248) = 4.76, p < .05, and of any substance (33.5% versus 18.2%), χ2 (1, N = 249) = 4.78, p < .05. Mean scores for Hawaiian youth participants were significantly higher than non-Hawaiian youth on all HYDOS subscales (Peer Pressure, t[226] = 3.45, p < .01; Family Drug Offers and Context, t[239] = 4.14, p < .001; Unanticipated Drug Offers, t[244] = 3.37, p < .01). However, when examining exposure to any of the items from each of the subscales, only exposure to items on the Family Drug Offers and Context subscale were significantly different between Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth (42.8% versus 23.6%), χ2 (1, N = 246) = 7.05, p < .01. There were no significant differences between Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth on any of the demographic variables (i.e., age, grade, SES, family structure, and gender). Crystalmethamphetamine use was highly skewed and rare in this study (only one participant reported having used it). Because of this, it was dropped as a separate dependent variable from the regression analyses.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 249)

| Hawaiian Youth | Non-Hawaiian Youth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (Percent) | Standard Deviation | Percent Non-zero^ | N | Mean (Percent) | Standard Deviation | Percent Non-zero^ | |

| Alcohol (last 4 weeks) | 190 | 0.63 | 1.06 | 31.6 | 55 | 0.20*** | 0.59 | 12.7** |

| Cigarettes (last 4 weeks) | 192 | 0.23 | 0.65 | 14.1 | 55 | 0.11 | 0.50 | 5.50 |

| Marijuana (last 4 weeks) | 193 | 0.29 | 0.78 | 14.5 | 55 | 0.09* | 0.55 | 3.60* |

| Crystalmeth (last 4 weeks) | 192 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.50 | 54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Other Hard Drugs (last 4 weeks) | 191 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 3.70 | 55 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 3.60 |

| Any Substance Use (last 4 weeks) | 193 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 33.5 | 55 | 0.10* | 0.36 | 18.2* |

| Peer Pressure | 194 | 0.34 | 0.70 | 43.3 | 55 | 0.13** | 0.27 | 41.8 |

| Family Offers/Context | 194 | 0.29 | 0.60 | 42.8 | 55 | 0.08*** | 0.21 | 23.6** |

| Unanticipated Drug Offers | 194 | 0.25 | 0.65 | 25.8 | 55 | 0.06** | 0.21 | 16.4 |

| Age | 193 | 11.92 | 0.85 | 55 | 11.69 | 0.88 | ||

| Grade | 193 | 7.05 | 0.73 | 55 | 6.89 | 0.71 | ||

| Gender (% female) | 192 | (57.2) | 55 | (65.5) | ||||

| Federal Lunch Participation (% yes) | 193 | (70.6) | 54 | (70.9) | ||||

| Two-Parent Household | 193 | (56.2) | 55 | (56.4) | ||||

Percentages represent those reporting any level of the behavior in the last 4 weeks

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001 from t-tests or chi-squared tests

Multivariate Analyses

The findings from the multivariate analyses using the full sample (with ethnicity as a predictor) produced similar results to those obtained from the Hawaiian subsample; therefore, only the latter model is presented. Logistic regression analysis results predicting recent substance use of Hawaiian youth are presented in Table 3. After controlling for several demographic variables, the analysis examines the influence of the HYDOS subscales on the use of specific substances, as well as any substance use, over the past 4 weeks. The regression results demonstrated that the Family Drug Offers and Context scale predicted recent alcohol use, the Peer Pressure and Family Drug Offers and Context scales predicted recent cigarette use, and the Unanticipated Drug Offers and Family Drug Offers and Context scales predicted recent marijuana use. Odds ratios for these relationships ranged from 17.44 to 2.75. The Family Drug Offers and Context Scale predicted the recent use of any substance (OR = 21.68). None of the independent variables were significant predictors of use of “hard drugs.”

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Substance Use of Native Hawaiian Youth in the Past 4 Weeks

| Alcohol (N = 188) | Cigarettes (N = 190) | Marijuana (N = 191) | “Hard Drugs” (N = 189) | Any Substance Use (N = 191) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | OR | B | OR | B | OR | B | OR | B | OR |

| Peer Pressure | 0.58 (0.57) | 1.78 | 1.46** (0.48) | 4.30 | 0.11 (0.48) | 1.12 | 0.88 (0.75) | 2.41 | 0.56 (0.56) | 1.75 |

| Family Offers/Context | 2.85** (0.79) | 17.28 | 1.00* (0.45) | 2.73 | 1.25* (0.49) | 3.49 | 0.97 (0.58) | 2.65 | 3.08** (0.82) | 21.68 |

| Unanticipated Drug Offers | 1.08 (0.63) | 2.94 | -0.96 (0.53) | 0.38 | 1.22* (0.54) | 3.39 | -0.35 (0.70) | 0.71 | 0.82 (0.57) | 2.28 |

| Age | 0.39 (0.25) | 1.48 | 0.06 (0.31) | 1.06 | 0.55 (0.35) | 1.73 | 0.70 (0.65) | 2.01 | 0.43 (0.24) | 1.54 |

| Federal Lunch Participation | -0.09 (0.48) | 0.91 | 0.40 (0.61) | 1.50 | 0.83 (0.69) | 2.30 | -0.35 (0.95) | 0.71 | -0.02 (0.46) | 0.98 |

| Two-Parent Household | -0.48 (0.43) | 0.62 | 0.12 (0.51) | 1.13 | -0.57 (0.56) | 0.57 | 1.21 (1.10) | 3.35 | -0.39 (0.42) | 0.68 |

| Gender (Male) | 0.61 (0.43) | 1.84 | -0.02 (0.53) | 0.98 | 0.60 (0.57) | 1.82 | 1.27 (1.10) | 3.56 | 0.72 (0.42) | 2.05 |

| Intercept | -5.22 | -3.19 | -9.31 | -13.62 | -5.67 | |||||

| χ 2 | 77.03 | 34.85 | 50.40 | 16.92 | 76.08 | |||||

| df | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.45 | |||||

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses

p < .05

p < .01

***p < .001

While none of the demographic variables (i.e., age, SES, family structure, and gender) were predictive of substance use in the model presented in Table 3, separate logistic regression models by gender (not presented) indicated that the Family Drug Offers and Context scale predicted alcohol use for both genders, but had a stronger effect for boys (B = 11.38, SE = 3.52, p < .01) than for girls (B = 1.79, SE = 0.78, p < .05). Further, the Peer Pressure scale was a significant predictor of cigarette use for boys only (B = 9.25, SE = 3.43, p < .01). These patterns of differential effects for boys and girls on the HYDOS subscales were confirmed by examining gender by subscale interactions using mean centered terms (models not presented). There were no significant gender differences in the effects of the three HYDOS subscales on use of marijuana, “hard drugs,” or the use of any substances.

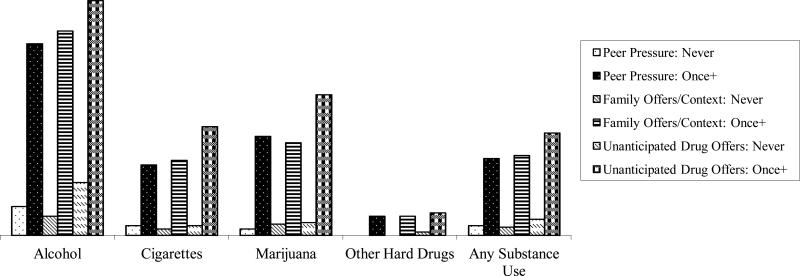

The size and direction of the effects presented in the regression analysis in Table 3 are further illustrated in Figure 1. Except for one instance, there were significant mean differences in drug use for those who were exposed at least once to drug offers on the HYDOS compared with those who were not exposed to them (all ps ≤ .01). “Hard drug” use of those exposed to unanticipated drug offers was not significantly different from those that were not exposed to them. Across all subscales, the largest mean differences occurred for alcohol use compared with the other substances.

Figure 1.

Mean Number of Times Hawaiian Youth Respondents Used Substances in the Last 4 Weeks as a Function of HYDOS Subscale Exposure (N = 194). “Any substance use” is the mean of the preceding four specific substances plus the use of “ice.”

Discussion

This study examined the differences in drug offers and drug use between Native Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth, and the influence of social and environmental factors on the drug-using behaviors of Native Hawaiian youth residing in rural communities. The majority of youth participants in the study appeared to be from low-income families. Further, the sample had a higher percentage of youth from low-income families compared with the total population within participating schools, which is most likely the result of oversampling for Native Hawaiian youth in this study. A higher percentage of Native Hawaiians live below the poverty threshold compared with the overall U.S. population (Harris & Jones, 2005). Consistent with other prevalence studies (Lai & Saka, 2005; Wong et al., 2004), Hawaiian youth in this study used alcohol and marijuana significantly more often than non-Hawaiian youth. Although overall recent drug use rates were low, Hawaiian youth in this study had significantly higher overall drug use rates, and used alcohol and marijuana at rates approximately three times higher than their non-Hawaiian counterparts. Most research has found that the lowest rates of youth substance use are in the Chinese and Japanese populations in Hawai‘i (e.g., Wong, Klingle, & Price, 2004; Mayeda et al., 2006). Because the non-Hawaiian subsample was primarily Filipino, the results are most likely not skewed because of ethnicity in this study. The higher rates of drug use for Hawaiian youth suggest that these youth may be at increased risk for drug abuse and drug-related health and behavioral problems as they enter adolescence. Further, Hawaiian youth had significantly higher mean scores than non-Hawaiian youth on all three subscales on the HYDOS—indicating more frequent encounters with all evaluated drug offer situations—and had a higher rate of exposure to at least one of the situations related to family drug offers and context. These findings suggest that family drug offers and context as described in the HYDOS are relatively unique to Hawaiian youth within the sampled schools.

Logistic regression results revealed that peer pressure, family drug offers and context, and unanticipated drug offers differentially influenced substance use of rural Hawaiian youth. They also revealed that family drug offers and context predicted the use of the widest variety of substances. Research has indicated that Native Hawaiian youth interact with a significantly greater number of family members than non-Hawaiian youth (Goebert et al., 2000). The findings from this study further suggest that these interactions significantly influence substance-using behaviors of rural Hawaiian youth. Similar findings have been reported with other indigenous youth populations (Kulis et al., 2006). The influence of family members on drug use in this study is also consistent with research which has found that family factors may intensify both risk and protection for drug use of Native youth populations (Okamoto et al., 2009; Waller et al., 2003). Family influence particularly affected alcohol use and the use of any substances in this study, as youth who had been exposed to family drug offers or context had odds of using alcohol or any substances many times higher than youth who did not receive offers from family members. These findings were further corroborated by examining the size and direction of effects in Figure 1. Overall, the findings indicated that drug offers within a familial context were particularly salient for rural Hawaiian youth, and were a strong predictor of drug use (particularly alcohol use) for these youth.

Finally, the findings revealed gender differences in the influence of family and peer offers on the use of alcohol and cigarettes, respectively. Although prior research indicated that rural Hawaiian girls are at higher risk for drug offers and report more difficulty in refusing drugs in offer situations (Okamoto, Kulis, et al., 2010), the social context may place rural Hawaiian boys at higher risk for actual drug use based on the present findings. The findings further suggest that the developmental and social context of drug use may be different for Hawaiian boys and girls, similar to research focused on other Native youth populations (e.g., Novins & Mitchell, 1998). More research is needed to examine the relationship between gender, drug offers, and drug use of rural Hawaiian youth.

Implications for Practice

To date, there have been very few drug prevention programs developed for these youth, and those that have been developed are in the initial stages of program development and evaluation (Edwards, Giroux, & Okamoto, 2010). For example, Hui Mālama O Ke Kai (Hishinuma et al., 2009) and the Pono Curriculum (Kim, Withy, Jackson, & Sekiguchi, 2007) both incorporate activities based on cultural metaphors and values, such as mālama ‘āina (caring for the land), or caring for ‘ohana (family). Both of these programs have been shown to modestly influence anti-drug use attitudes. The findings from the present study have implications for interventions with Hawaiian youth in rural communities. Because Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian youth from the same communities demonstrated several differences in exposure to drug offers and drug use, there is most likely a need for drug prevention programs that are culturally specific to Hawaiian worldviews, values, and beliefs in order to address these differences. Ideally, these programs would incorporate immediate and extended family members in their content and/or delivery, in order to maximize effectiveness. The findings also indicate that prevention of alcohol use is particularly important for rural Hawaiian youth. Thus, skills training might incorporate alcohol related problem situations involving cousins, aunts or uncles, and parents within a variety of realistic settings in order to promote drug resistance for these youth. The findings also suggest that drug prevention may need to engage family members as active participants. This might include school- or community-based group interventions with sets of same-generation family members (e.g., cousins and siblings), or community-based multiple family interventions (e.g., interventions incorporating sets of immediate and extended family members within a community). Resistance skills training should also focus on identifying peer-related settings and/or situations involving drug use, in order for rural Hawaiian youth to avoid exposure to drug offers.

This study contributes to a developing body of pre-prevention research focused on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use (Edwards et al., 2010; Okamoto, Kulis, et al., 2010; Okamoto, Helm, et al. 2010). Collectively, this body of research can inform existing evidence-based drug prevention programs through cultural adaptation efforts; however, the process of adapting existing interventions to unique cultural groups can be complex and difficult (Castro, Barrera, & Holleran-Steiker, 2010). Due to the cultural uniqueness of Native Hawaiians, Okamoto (2010) has argued for the development of a culturally grounded drug prevention program for these youth. Culturally grounded prevention is based on the norms, values, and beliefs of a specific population or subpopulation. While culturally grounded drug prevention programs can be costly to develop, they may be an important investment for this population, not only to address the disparate rates of substance use for Hawaiian youth (as demonstrated in this study), but also because a Hawaiian-focused drug prevention program could serve as a “template” for prevention adaptation efforts to other indigenous and Pacific Islander youth populations throughout the Pacific Rim.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations. Because active parental consent was required for participation in the study, it may have been influenced by a selection bias. Study feedback received from the participating schools indicated that some of the most high-risk students were not given parental consent to participate in the study. This might have affected the rates of drug use and exposure to drug offers reported in this study. The selection bias limited the ability for specific subgroup analyses (such as analysis of substance-using versus non-substance-using youth) in this study. The study was also limited in the measurement of drug use. Substance use was measured by number of uses, rather than total amount of drinking, therefore it is difficult to discern the amount of substances used or consumed by participants. Because survey questions were read aloud to participants, response reactivity (i.e., reporting lower than actual substance use) could have resulted from the perceived researcher's bias in reading of the items. Further, because the study was geographically focused on one island, the findings may lack generalizability to Hawaiian youth on other islands. Future research might examine the ecological context of drug offers across multiple islands within Hawai‘i in order to establish generalizable settings and situations. Finally, due to the length of the survey and time constraints in survey administration, additional items assessing the relationship of the survey responses to social desirability were not included. Respondents may have either downplayed or exaggerated their drug use and experience with drug offers, which was not assessed in the study.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations, this study has implications for understanding the culturally-specific drug use etiology and prevention practices of Native Hawaiian youth in rural communities. Using comparisons to a non-Hawaiian subsample, it validates the unique influence of family drug offers and context on drug use of rural Hawaiian youth, which has been described in earlier exploratory research (Okamoto et al., 2009; Okamoto, Helm, et al., 2010). Further, it is also consistent with research on other Native youth populations, which has highlighted familial influences in drug use (Hurdle et al., 2003; Waller et al., 2003). Future research might examine family drug offers and context more closely, in order to determine the influence of specific offerer subgroups (e.g., cousins, parents, etc.) and settings (e.g., family parties). Future research might also examine the causal factors related to the higher frequency of peer and unanticipated drug offers for rural Hawaiian youth, as compared with their non-Hawaiian counterparts.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01 DA019884), with supplemental funding from the Trustees’ Scholarly Endeavors Program, Hawai‘i Pacific University. Data analysis for this study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20 MD002316). A version of this article was presented at the 14th Annual Society for Social Work and Research conference in San Francisco, CA, January 2010.

Contributor Information

Scott K. Okamoto, School of Social Work, Hawai‘i Pacific University.

Stephen Kulis, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University.

Susana Helm, Department of Psychiatry, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Christopher Edwards, Healing Minds, LLC, Reno, NV.

Danielle Giroux, Clinical-Community Psychology Program, University of Alaska Anchorage..

References

- Accountability Resource Center Hawai‘i [November 21, 2008];School accountability: School status and improvement report. 2007 from http://arch.k12.hi.us/school/ssir/2007/hawaii.html.

- Affonso DD, Shibuya JY, Frueh BC. Talk-story: Perspectives of children, parents, and community leaders on community violence in rural Hawaii. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24(5):400–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CS, Allen P, Crawford MA, McCormick LK. Taking a first puff: Cigarette smoking experiences among ethnically diverse adolescents. Ethnicity & Health. 1999;4(4):245–257. doi: 10.1080/13557859998038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Holleran-Steiker L. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon Rayle A, Kulis S, Okamoto SK, Tann SS, LeCroy CW, Dustman P, et al. Who is offering and how often? Gender differences in drug offers among American Indian adolescents of the Southwest. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;26(3):296–317. doi: 10.1177/0272431606288551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Giroux D, Okamoto SK. A review of the literature on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use: Implications for research and practice. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9(3):153–172. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2010.500580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else IRN, Andrade NN, Nahulu LB. Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among Indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Studies. 2007;31:479–501. doi: 10.1080/07481180701244595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Maskarinec G, Carlin L. Ethnicity, sense of coherence, and tobacco use among adolescents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29(3):192–199. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2903_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebert D, Nahulu L, Hishinuma E, Bell C, Yuen N, Carlton B, et al. Cumulative effect of family environment on psychiatric symptomatology among multiethnic adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:34–42. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PM, Jones NA. We the people: Pacific Islanders in the United States. U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hawai‘i Department of Health . State of Hawai‘i primary care needs assessment data book 2005. Family Health Services Division, Hawai‘i Department of Health; Honolulu, HI: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Okamoto SK, Medeiros H, Chin CIH, Kawano KN, Po‘a-Kekuawela K, et al. Participatory drug prevention research in rural Hawai‘i with Native Hawaiian middle school students. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2008;2(4):307–313. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishinuma ES, Chang JY, Sy A, Greaney MF, Morris KA, Scronce AC, et al. Hui Mālama O Ke Kai: A positive prevention-based youth development program based on Native Hawaiian values and activities. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37(8):987–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Hishinuma ES, Else IRN, Chang JY, Goebert DA, Nishimura ST, Choi-Misailidis S, et al. Substance use as a robust correlate of school outcome measures for ethnically diverse adolescents of Asian/Pacific Islander ancestry. School Psychology Quarterly. 2006;21(3):286–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hurdle DE, Okamoto SK, Miles B. Family influences on alcohol and drug use by American Indian youth: Implications for prevention. Journal of Family Social Work. 2003;7(1):53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS, Ziedonis D, Chen K. Tobacco use and dependence in Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents: A review of the literature. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6(3/4):113–142. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R, Withy K, Jackson D, Sekaguchi L. Initial assessment of a culturally tailored substance abuse prevention program and applicability of the risk and protective model for adolescents of Hawai‘i. Hawai‘i Medical Journal. 2007;66:118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Okamoto SK, Dixon Rayle A, Sen S. Social contexts of drug offers among American Indian youth and their relationship to drug use: An exploratory study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12(1):30–44. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M, Saka S. [April 14, 2008];Hawaiian students compared with non-Hawaiian students on the 2003 Hawaii Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2005 from http://www.ksbe.edu/spi/PDFS/Reports/Demography_Well-being/yrbs/

- Liu DMKI, Blaisdell RK, Aitaoto N. Health disparities in Hawai‘i, Part 1. Hawai‘i Journal of Public Health. 2008;1(1):5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Makini GK, Hishinuma ES, Kim SP, Carlton BS, Miyamoto RH, Nahulu LB, et al. Risk and protective factors related to Native Hawaiian adolescent alcohol use. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2001;36(3):235–242. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda DT, Hishinuma ES, Nishimura ST, Garcia-Santiago O, Mark GY. Asian/Pacific Islander Youth Violence Prevention Center: Interpersonal violence and deviant behaviors among youth in Hawai‘i. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse . Five-year strategic plan 2009. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Novins DK, Mitchell CM. Factors associated with marijuana use among American Indian adolescents. Addiction. 1998;93:1693–1702. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931116937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK. Culturally grounded drug prevention for Native Hawaiian youth: Next steps for the Promoting Social Competence and Resilience Project; Grand rounds lecture presented at the John A. Burns School of Medicine; University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI. 2010, November. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Giroux D, Edwards C, Kulis S. The development and initial validation of the Hawaiian Youth Drug Offers Survey (HYDOS). Ethnicity & Health. 2010;15(1):73–92. doi: 10.1080/13557850903418828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Po‘a-Kekuawela K, Chin CIH, Nebre LH. Community risk and resiliency factors related to drug use of rural Native Hawaiian youth: An exploratory study. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2009;8(2):163–177. doi: 10.1080/15332640902897081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Edwards C, Giroux D. Gender differences in drug offers of rural Hawaiian youth: A mixed methods analysis. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work. 2010;25(3):291–306. doi: 10.1177/0886109910375210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, LeCroy CW, Dustman P, Hohmann-Marriott B, Kulis S. An ecological assessment of drug related problem situations for American Indian adolescents of the Southwest. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2004;4(3):47–63. doi: 10.1300/J160v04n03_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Goebert D, Nishimura S. Ethnic variation in drinking, drug use, and sexual behavior among adolescents in Hawaii. Journal of School Health. 2004;74:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehuher D, Hiramatsu T, Helm S. Evidence-based youth drug prevention. A critique with implications for practice-based contextually relevant prevention in Hawai‘i. Hawai‘i Journal of Public Health. 2008;1(1):52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R. Opportunities to meet challenges in rural prevention research: Findings from an evolving community-university partnership model. The Journal of Rural Health. 2007;23(suppl.):42–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsark J, Blaisdell R, Aluli NE, editors. The health of Native Hawaiians (special issue). Pacific Health Dialog. 1998;5:228–404. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Services data sets: Rural definitions. [June 28, 2009];2007 from http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/Ruraldefinitions/HI.pdf.

- Wallace JM, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM, Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students, 1976-2000. Addiction. 2003;98:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitzfelder BE, Engel CC, Gilbert FI. Substance abuse in Hawaii: Perspectives of key local human service organizations. Substance Abuse. 1998;19(1):7–22. doi: 10.1080/08897079809511369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller MA, Okamoto SK, Miles BW, Hurdle DE. Resiliency factors related to substance use/resistance: Perceptions of Native adolescents of the Southwest. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare. 2003;30(4):79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Withy K, Andaya JM, Mikami JS, Yamada S. Assessing health disparities in rural Hawaii using the Hoshin facilitation method. The Journal of Rural Health. 2007;23(1):84–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Klingle RS, Price RK. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents in California and Hawaii. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen NYC, Nahulu LB, Hishinuma ES, Miyamoto RH. Cultural identification and attempted suicide in Native Hawaiian adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(3):360–367. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200003000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]