Abstract

Agriculturally important grasses such as rice, maize, and sugarcane are evolutionarily distant from Arabidopsis, yet some components of the floral induction process are highly conserved. Flowering in sugarcane is an important factor that negatively affects cane yield and reduces sugar/ethanol production from this important perennial bioenergy crop. Comparative studies have facilitated the identification and characterization of putative orthologs of key flowering time genes in sugarcane, a complex polyploid plant whose genome has yet to be sequenced completely. Using this approach we identified phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP) gene family members in sugarcane that are similar to the archetypical FT and TFL1 genes of Arabidopsis that play an essential role in controlling the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. Expression analysis of ScTFL1, which falls into the TFL1-clade of floral repressors, showed transcripts in developing leaves surrounding the shoot apex but not at the apex itself. ScFT1 was detected in immature leaves and apical regions of vegetatively growing plants and, after the floral transition, expression also occurred in mature leaves. Ectopic over-expression of ScTFL1 in Arabidopsis caused delayed flowering in Arabidopsis, as might be expected for a gene related to TFL1. In addition, lines with the latest flowering phenotype exhibited aerial rosette formation. Unexpectedly, over-expression of ScFT1, which has greatest similarity to the florigen-encoding FT, also caused a delay in flowering. This preliminary analysis of divergent sugarcane FT and TFL1 gene family members from Saccharum spp. suggests that their expression patterns and roles in the floral transition has diverged from the predicted role of similar PEBP family members.

Keywords: Saccharum spp., bioenergy crop, floral induction, FT-like genes, florigen orthologs, PEBP family

Introduction

Flowering time is a crucial and highly controlled mechanism in plants that has a direct impact on reproductive success and survival (Imaizumi and Kay, 2006). Moreover, the floral transition in crop plants is directly related to crop yield. In order to survive imminent seasonal changes, plants have developed core signaling pathways that integrate day-length perception with developmental reprogramming. Signals are initiated outside of the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and a response cascade is triggered, ultimately reaching the SAM where cellular changes occur, leading to the formation of reproductive structures instead of leaves. The study of flowering time mutants in Arabidopsis has been instrumental in defining six signaling pathways: photoperiodic, autonomous, vernalization, gibberellin, ambient temperature and age-dependent control (Fornara et al., 2010). FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT)/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1) are phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP) family members that are similar to mammalian PEBPs (Banfield et al., 1998; Ahn et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis, TFL1 is responsible for maintaining the inflorescence in an indeterminate state, with loss of TFL1 function resulting in the production of terminal flowers (Bradley et al., 1997). Although the TFL1 gene sequence is highly similar to FT, TFL1 acts antagonistically by delaying floral commitment (Hanzawa et al., 2005; Ahn et al., 2006). Whereas the FT protein interacts with the FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD) bZIP transcription factor at the SAM to promote flowering (Abe et al., 2005; Wigge et al., 2005), TFL1 protein similarly binds to FD to repress downstream genes such as APETALA 1 (AP1) and LEAFY (LFY) in the central zone of the meristem (Ratcliffe et al., 1999; Hanano and Goto, 2011). Opposite functions of TFL1 and floral meristem genes reflect their specific expression in separate domains. TFL1 is expressed in central cells of the SAM whereas the floral meristem genes are concentrated in the peripheral cells (Mandel et al., 1992; Kempin et al., 1995; Bradley et al., 1997). When floral meristem identity gene expression is reduced, flowers have shoot-like characteristics (Irish and Sussex, 1990; Schultz and Haughn, 1991, 1993; Huala and Sussex, 1992; Weigel et al., 1992; Bowman et al., 1993; Shannon and Meekswagner, 1993). Upon floral transition, TFL1 is up-regulated to maintain indeterminate inflorescence meristem and to counterbalance FT activity (Shannon and Meekswagner, 1991; Bradley et al., 1997; Ratcliffe et al., 1999; Conti and Bradley, 2007; Hanano and Goto, 2011; Jaeger et al., 2013).

Several structural and biochemical features of FT protein support the hypothesis that FT is a major component of the florigen that triggers floral evocation at the SAM (Taoka et al., 2013). FT is expressed in phloem-specific tissues under floral inductive long-day conditions (Takada and Goto, 2003; An et al., 2004) and is able to traffic long distances intercellularly from companion cells to the SAM (Jaeger and Wigge, 2007; Mathieu et al., 2007). Characterization of FT homologs that induce flowering in diverse species suggests that FT is a highly conserved florigen (Kojima et al., 2002; Lifschitz et al., 2006; Corbesier et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2007; Tamaki et al., 2007; Lazakis et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2011). For example, the rice FT ortholog, Heading date3 (Hd3a), is a mobile signal synthesized in leaves that is capable of reaching the SAM (Kojima et al., 2002; Tamaki et al., 2007); Zea mays CENTRORADIALIS8 (ZCN8) gene is expressed in the leaf and is able to induce flowering in Arabidopsis ft mutants when expressed under the control of a phloem-specific promoter (Lazakis et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2011); the tomato SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS (SFT) dependent graft-transmissible elements complement developmental defects in sft mutants and substitute long-day conditions in Arabidopsis (Lifschitz et al., 2006). In addition, the Beta vulgaris floral inducer FT2 (BvFT2) is needed for normal flower initiation in sugar beet (Pin et al., 2010).

Plants typically have more than one FT related homolog, and domain analysis suggests that variation in specific regions of the FT protein are responsible for alternative functions, such as floral repression (Hanzawa et al., 2005; Ahn et al., 2006; Pin et al., 2010; Blackman et al., 2011; Harig et al., 2012). These observations, and comparison of FT function in various plant species suggests that the ancestor of FT is a floral repressor (Karlgren et al., 2011; Harig et al., 2012). Augmenting the acknowledged role of FT in flowering time, recent discoveries associate FT function with other meristem-related mechanisms (Bohlenius et al., 2006; Shalit et al., 2009; Navarro et al., 2011), consolidating FT as a key mobile signal that is not only related to floral transition but also related to diverse developmental events in plants.

Perennial plants depend on the maintenance of growth through several seasons, balancing nutritional status, biomass accumulation, and alternating vegetative and reproductive growth over the years. Flowering time genes are largely conserved between annual and perennial plants (Albani and Coupland, 2010), however perennial plants also must account for plant age to coordinate competence to flower. In the perennial Arabis alpina, sensitivity to vernalization depends on plant age; a condition which the PEBP member gene, AaTFL1, sets as a threshold to control the age-dependent pathway to flowering (Wang et al., 2011; Bergonzi et al., 2013). In perennial sugarcane, a qualitative short-day plant, little is known about the genetic control of floral induction. The transition to reproductive growth is undesirable in commercial sugarcane cultivars because the production of floral structures redirects carbon assimilates from stalks to inflorescences and results in loss of accumulated sucrose (Berding and Hurney, 2005). Therefore understanding the genetic underpinnings of flowering time in sugarcane provides a basis for the development of new strategies to improve agronomic traits such as increased biomass and sugar production in this important food and bioenergy crop. Here we isolate and characterize two novel sugarcane PEBP members and show that they alter flowering time and floral architecture in Arabidopsis.

Materials and methods

Plant growth conditions and genotyping

Sugarcane plants, variety RB72 454, were grown in a greenhouse under either 14-h long-day conditions at 27°C with 10-h nights at 22°C, or 12-h short-day inductive conditions representing field conditions with 20-20-20 NPK fertilizer supplemented with micronutrients added as required. Arabidopsis plants, ecotype Columbia (Col-0), were cultivated in Conviron growth chambers under conditions of 16-h days at 23°C with 8-h nights at 21°C, with a light intensity of 120 μmolm−2s−1 and 60% humidity. Arabidopsis plants with segregating transgenes were genotyped using the Sigma REDExtract-N-Amp Plant PCR Kit (Sigma Biosciences) following manufacturer's instructions, and PCR was performed using kanamycin primers - KanrF: 5'-ATACTTTCTCGGCAGGAGCA-3' and KanrR: 5'-ACAAGCCGTTTTACGTTTGG-3'.

Isolation and cloning of FT/TFL1 homologs from sugarcane leaves

Mature and immature leaf tissues from sugarcane plants under inductive and non-inductive conditions were collected for total RNA extraction (TRIzol Reagent) and genomic DNA as previously described (Colasanti et al., 1998). For RNA assays, complementary cDNA was synthesized using the qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta Bioscences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequences were amplified using specific primers designed at the UTR region of the genes: ScTFL1F: 5'-GTCCGATTAGCTTGCTGCAT-3'; ScTFL1R: 5'-GGCCATGCTCATAACTTTGG-3'; ScFT1F: 5'-ATATGGCTAATGACTCCCTGACG-3'; ScFT1R: 5'-CTGGACATGAGGGGTAGGTAAAT-3'. Genomic and complementary ScTFL1/ScFT1 sequences were cloned to the CloneJET PCR Cloning Gene (Thermo Scientific) and sequenced.

Phylogenetic analysis of the ScTFL1 and ScFT1 candidates with orthologs of related species

Deduced amino acid sequences of sugarcane ScTFL1/ScFT1 compared to homologs from other species were aligned with translated sequences for Arabidopsis TFL1 and FT; ZCN1, ZCN2, and ZCN8 (maize); RCN1 and Hd3a (rice); NtFT1 to NtFT4 (tobacco); and BvFT1 and BvFT2 (sugar beet), using the software BioEdit 7.1.3.0 (Hall, 1999). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by MEGA software, version 4.0 (Tamura et al., 2007), with the neighbor-joining comparison model (Saitou and Nei, 1987), p-distance method and pair-wise deletion. Bootstrap values from 1000 replicates were used to assess the robustness of the trees (Felsenstein, 1985). Phylogenetic analysis that included the deduced amino acid sequences of incomplete sugarcane genes was corrected by deleting positions with gaps from the alignment. Gene structure information for homologs was accessed at the Phytozome 9.1 genome database available online (www.phytozome.net).

Construction of overexpression vector and arabidopsis transformation

Candidate genes for TFL1 and FT amplified from sugarcane leaf RNA were cloned into Gateway entry vector pDONR-221 using the BP recombination reaction and the subsequent products were recombined with the destination vector pK2GW7 by a LR clonase originating from the expression vector 35S::ScTFL1 and 35S::ScFT1. Gateway sites were added to the sequencing primers for cloning purposes as follows:

ScTFL1gatF: 5'-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGTCCGATTAGCTTG-CTGCAT-3' and ScTFL1gatR: 5'-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGGCCATG-CTCATAACTTTGG-3' and ScFT1gatF: 5'-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGC-TATATGGCTAATGACTCCCTGACG-3' and ScFT1gatR: 5'-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAA-GAAAGCTGGGTCTGGACATGAGGGGTAGGTAAAT-3'. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101::pMP90 containing the over-expression constructs were introduced into Arabidopsis plants by floral dip (Clough and Bent, 1998). Agrobacterium containing ScTFL1 and ScFT1 over-expression constructs were introduced to the Columbia (Col-0) ecotype. Fifty T1 individuals overexpressing ScTFL1 and 18 T1 lines carrying the 35S::ScFT1 construct germinated on MS plates supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and resistant seedlings were transplanted to soil to obtain T2 seeds. Segregation analysis showed that 20 and 14 T2 lines, respectively, had single insertions of the 35S::ScTFL1 and 35S::ScFT1 transgenes (X2 test, p < 0.05). All individuals with the transgene showed the late flowering phenotype whereas segregants without the transgene flowered normally. Ten individuals from four independent single insertion lines each that were homozygous for the transgene were selected for phenotypic analyses of ScTFL1 and ScFT1 overexpression. Flowering time was scored by counting the number of rosette leaves at the appearance of the first floral bud in primary inflorescences.

Gene expression analysis using semi-quantitative and quantitative RT-PCR

Gene and transgene expression analysis was carried out using semi-quantitative RT-PCR and real time RT-PCR. For ScTFL1 and ScFT1 expression analysis, RNA was extracted as described above from sugarcane mature leaves, immature leaves and the SAM enriched region. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared using qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. ScTFL1 primers were designed to assess transgene expression in the ScTFL1 transgenic lines: ScTFL1qRTF: 5'- GACTTGCGGTCTTTCTTCACA -3'; ScTFL1qRTR: 5'- AGGCATCTGTTGTCCCAGGT -3'. Expression of the ScFT1 gene in transgenic plants was assessed by qRT-PCR analysis with the primers ScFT1qPCR-F (GGCTAATGACTCCCTGACGA) and ScFT1qPCR-R (CCATCCCTT CAAACACTGGT). PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences) and an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real Time PCR instrument were used, and data was analyzed by the Pfaffl method with efficiency correction to obtain fold difference in expression (Pfaffl, 2001). Three biological replicates of three technical replicates were analyzed. Actin8 (ActinrtF: 5'-GCCGATGCTGATGACATTCA-3' and ActinrtR: 5'-CTCCAGCGAATCCAGCCTTA-3') and ScGAPDH (ScGAPDHF: 5'-CACGGCCACTGGAAGCA-3' and ScGAPDHR: 5'-TCCTCAGGGTTCCTGATGCC-3') were used for normalization and the calibrator was the average ΔCt for the independent line with lower expression level. Statistical significance is reported by the Student's t-test with P < 0.05.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

At least three inflorescences per plant were harvested from ScTFL1 over-expressed plants and images were captured with a Hitachi Tabletop TM-1000 Scanning Electron Microscope. Dimension bars were added using the ImageJ software (Abràmoff et al., 2004).

Results

Isolation of a TFL1 homolog from saccharum spp. and expression analysis in different tissues

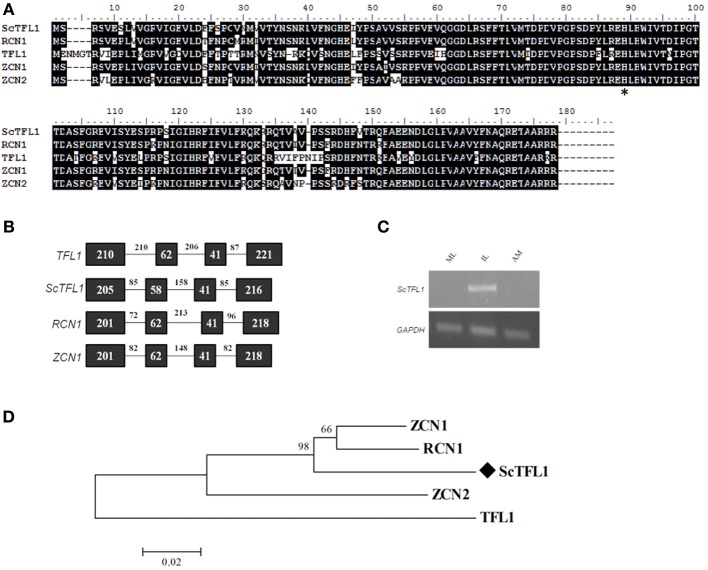

Candidates for FT/TFL1 gene family members were identified in the sugarcane EST database, SUCEST (Vettore et al., 2001; Coelho et al., 2013). A complete sequence for a TFL1-like subfamily candidate was identified and termed ScTFL1. The deduced ScTFL1 protein had highest similarity to maize genes ZCN1 and ZCN2 proteins (93 and 84% amino acid identity, respectively), 92% identity to rice RCN1, and 70% identity to Arabidopsis TFL1 (Figure 1A). ScTFL1 sequence is more similar to the rice and maize homologs compared to Arabidopsis (Figure 1D). The founding member of this family, Arabidopsis TFL1, is highly conserved between species, and homologs have been reported in several different species (Hecht et al., 2005; Danilevskaya et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2010; Mauro-Herrera et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Sequence conservation among TFL-like genes. (A) Alignment of the ScTFL1 candidate with homologs from different species: Arabidopsis TFL1; rice RCN1; and maize ZCN1. Asterisk (*) highlights the amino acid residue conserved in all TFL1 homologs. (B) TFL1 gene structure conservation among TFL1 homologs, consisting of four exons and three introns. Boxes represent exons and lines, introns. Numbers indicate size of each exon and intron. (C) Expression pattern of ScTFL1 in different tissues by semi-quantitative PCR; sugarcane GAPDH endogenous control was used as control. IL: apex-surrounding immature leaves; ML, mature leaves; AM, apical meristem. (D) Evolutionary relationship of TFL1 homologs. Amino acid sequences from different species were aligned using ClustalW, the evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). Bootstrap values from 1000 replications were used to assess the robustness of the trees. Sugarcane TFL1 candidate gene is highlighted by a diamond symbol (♦) and TFL1 homologs from related species are deposited at the Genbank database. Accession numbers: ZCN1 (ABX11003.1), ZCN2 (ABX11004.1), RCN1 (ABA95827.1), and TFL1 (AED90661.1), ScTFL1 (KJ496328).

Plant PEBP proteins are general regulators of signaling complexes, as shown by the tomato SELF PRUNNING (SFP) protein, a TFL1 homolog that acts through interaction with different proteins (Pnueli et al., 2001). The PEBP family consists of three gene subfamilies named MOTHER-of-FT (MFT)-like, TFL1-like and FT-like (Chardon and Damerval, 2005). In sugarcane, eight candidate PEBP gene family members were identified by in silico analysis in the sugarcane database and found to belong to several different subfamilies; one MFT-like gene, one TFL1-like and six FT-like candidates (Coelho et al., 2013). Six members of the TFL1-like subfamily were reported in maize, ZCN1 to ZCN6 (Danilevskaya et al., 2010), and four members were identified in rice: Oscen1 to Oscen4 (Nakagawa et al., 2002). Completion of the sugarcane genome sequence likely will reveal more PEBP members in this species.

Comparing the deduced ScTFL1 amino acid sequence to known TFL1-like homologs from other plant species shows that they all share a histidine residue at position 89 (H89) (Figure 1A); in Arabidopsis this residue is at a key position that determines whether TFL1 or FT act as a floral repressor or promoter, respectively (Hanzawa et al., 2005). The gene structure of ScTFL1 is similar to the related TFL1 orthologs, consisting of three introns and four exons of similar sizes. (Figure 1B). The fourth exon contains a specific region, segment B, that is critical for FT to function as a floral promoter or TFL1 as a floral repressor (Ahn et al., 2006). Residues Gln140, Asp144 and Glu141 (found in FT, TFL1, and BFT, respectively) of segment B may have an important function in determining FT-like or TFL1-like activity (Ahn et al., 2006; Yoo et al., 2010). This segment forms an external loop that varies in TFL1 but not in FT, and it seems that the opposite activity in flower induction is derived from hydrogen bond formation near the binding pocket in TFL1 but not in FT, suggesting that this segment is crucial for the co-activation of specific, yet-to-be identified FT/TFL1 interactors (Ahn et al., 2006; Pin et al., 2010; Taoka et al., 2011; Harig et al., 2012; Taoka et al., 2013). Consistent with this, FT has a tyrosine residue at position 85 (Y85), a key difference that specifies FT function as a floral promoter in Arabidopsis (Hanzawa et al., 2005), although in some species it has been reported that the FT-likes containing the Y85 residue may act as a floral repressor if there is variation in segment B.

We determined the expression pattern of ScTFL1 at the vegetative apical meristem region, mature leaves and the immature leaves surrounding the meristem in 7-month old sugarcane plants. ScTFL1 is expressed in the young leaves that enfold the meristem, however no transcript was detected in the shoot apical region. (Figure 1C). In Arabidopsis, TFL1 is expressed in young axillary meristems and is later confined to the central core of the meristem (Conti and Bradley, 2007). The ScTFL1 expression pattern suggests that this gene acts in regions adjacent to the meristem in vegetative sugarcane plants. Similarly, in maize, which is an annual plant, ZCN1 and ZCN2 are expressed in both vegetative and reproductive phases, with ZCN1 mRNA detected in vascular bundles of leaf primordia and ZCN2 in leaf axils of shoot apices (Danilevskaya et al., 2010).

Ectopic expression of ScTFL1 alters flowering time and maintains indeterminate fate of inflorescence meristems in transgenic arabidopsis plants

To understand the role played by this sugarcane TFL1 homolog, we examined transgenic Arabidopsis plants over-expressing the ScTFL1 driven by the constitutive 35S CaMV promoter. More than 40 transgenic lines were isolated and found to flower later than wild-type; four independent T2 lines homozygous for the transgene (ScTFL1-5; ScTFL1-6; ScTFL1-11, and ScTFL1-41) were selected for further analysis. The prolonged vegetative phase was manifested as an increase in the number of rosette leaves in all transgenic lines, ranging from 15.4 to 17.7 leaves on average, compared to the 11.4 leaves in Col-0 plants (Table 1). All four lines had ectopic expression of the ScTFL1 transgene, however the differences in flowering time did not correlate with the level of exogenous transcript (Supplemental Figure 1A). Otherwise there were no morphologic differences in vegetative structures, such as the serrated leaves that were reported from over-expression of the BROTHER of FT and TFL1 (BFT) gene in Arabidopsis (Yoo et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Flowering characteristics of four 35S::ScTFL1 independent transgenic lines.

| Plant genotype | Days to flowering | Number of leaves | Number of plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Col-0 wild-type | 32 | 11.4 ± 0.54 | 5 |

| ScTFL1-5 | 41 | 15.4 ± 1.35a | 10 |

| ScTFL1-6 | 41 | 14.3 ± 1.34a | 10 |

| ScTFL1-11 | 41 | 15.2 ± 1.73a | 10 |

| ScTFL1-41 | 47 | 17.7 ± 1.60a | 10 |

Indicates statistically different from wild-type with p > 0.05 by student t-test.

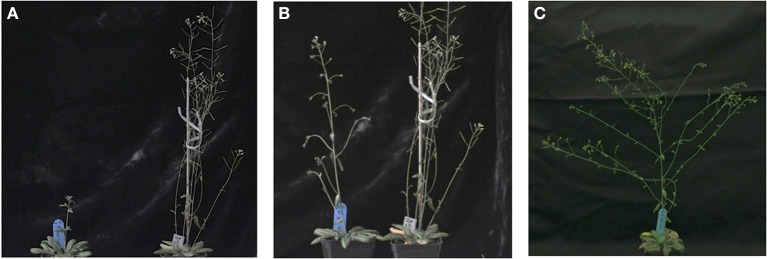

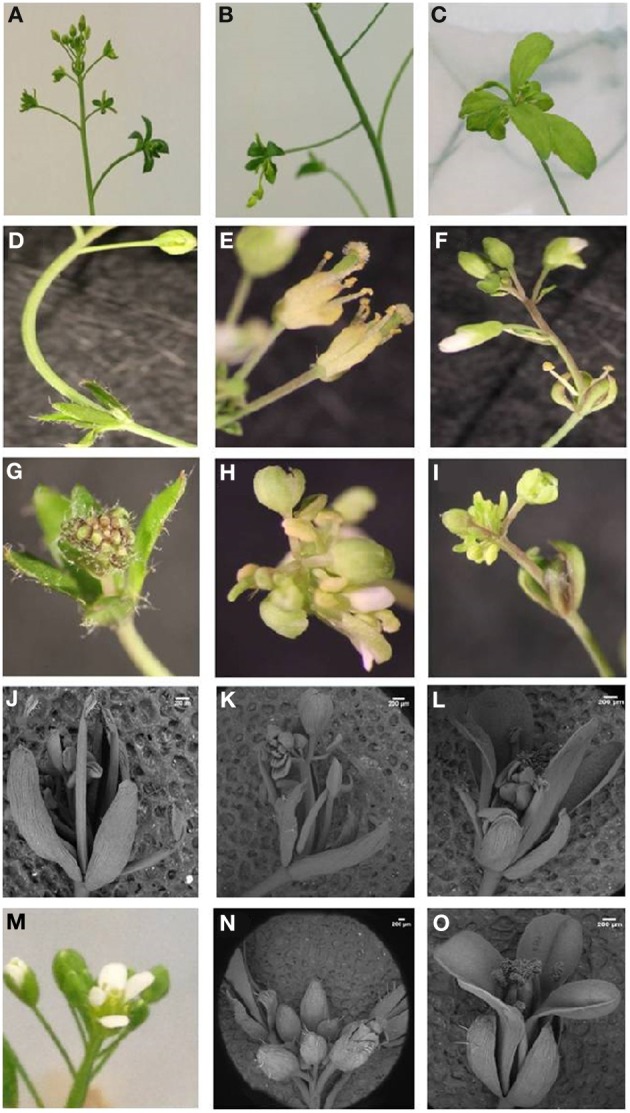

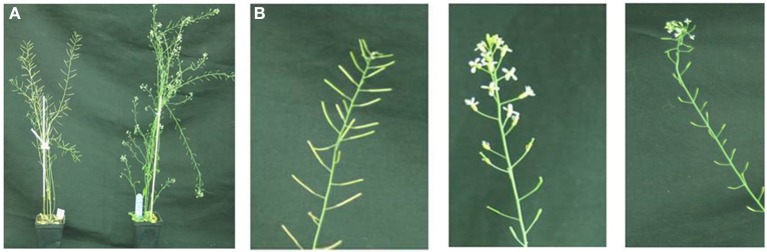

With regard to reproductive development, ectopic expression of ScTFL1 altered flowering time (Table 1; Supplemental Figure 2) but also affected the formation of the inflorescence structures, as typified in the most severe line, ScTFL1-41 (Figure 2A). The other late flowering lines examined, ScTFL1-5, -6 and -11, showed similar defects in reproductive architecture, although to a lesser extent than the most severe line ScTFL1-41 which was also exhibited the latest flowering. In addition ScTFL1-41 plants had a highly branched phenotype (Figures 2B,C), shoot-like inflorescences, aerial rosettes, abnormal flower formation (Figure 3), and prolonged life cycle (>64 days). A similar phenotype was reported in Arabidopsis over-expressing TFL1 and TFL1-like BFT, and their respective rice and maize homologs; i.e., in developmental phases were delayed and similar effects on plant architecture were observed (Ratcliffe et al., 1998, 1999; Jensen et al., 2001; Nakagawa et al., 2002; Danilevskaya et al., 2010; Yoo et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

Ectopic ScTFL1 expression affects inflorescence architecture in transgenic Arabidopsis. (A) Growth of 35S::ScTLF1-41 transgenic plants (left) and Col-0 (right) under long-day conditions after 50 days; and (B) 55 days; and (C) 64 days of germination, at this point Col-0 wild-type plants have completed the life cycle. All plants are in the Col-0 background.

Figure 3.

ScTFL1 transgenic plants phenotypes. (A–D) Examples of aerial rosettes phenotype of 35S::ScTFL1 lines. (E–I) Abnormal flower formation in emerging floral buds. (J–L) Scanning electronic microscopy (SEM) showing floral buds emerging from 35S::ScTF1 inflorescences. (M–O) Wild-type flower and inflorescences. Scale bars: 200 μm.

ScFT1 is a putative FT ortholog that delays flowering in arabidopsis

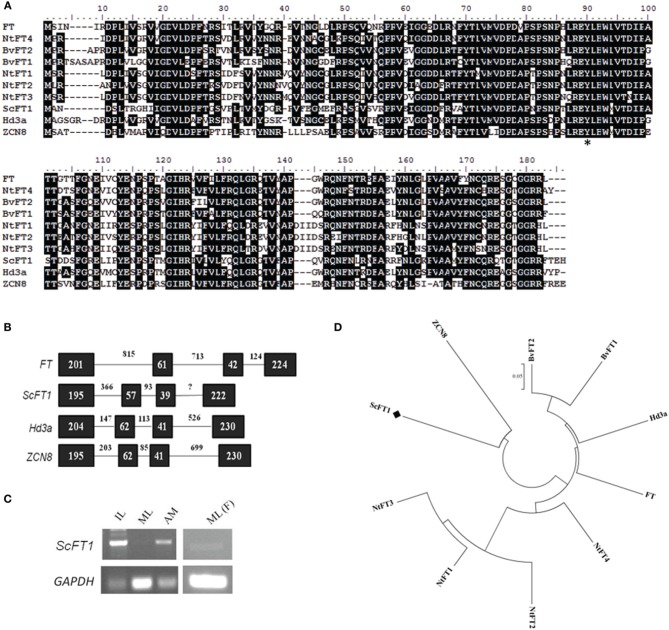

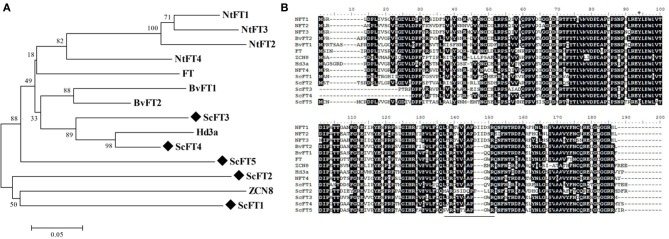

In parallel with the characterization of ScTFL1, we isolated ScFT1 from mature sugarcane plants and compared the sequence and expression pattern to Arabidopsis FT and other homologs. Comparison of the ScFT1 deduced protein with FT homologs from different species (Figure 4A) showed it to be 59% identical to Arabidopsis FT, 59% to rice Hd3a; 57% to maize ZCN8; 62% to sugar beet BvFT2 and 61% to tobacco NtFT4. Sugar beet and tobacco candidates that act antagonistically to flowering had less similarity to ScFT1: NtFT1, -2, -3 were 57, 54, and 54%, respectively, and the sugar beet BvFT1, 59%.

Figure 4.

Sequence conservation among FT-like genes. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of ScFT1 candidate with homologs from different species: Arabidopsis FT, rice Hd3a; and maize ZCN8; tobacco NtFT1-4; sugar beet BvFT1/2. Asterisk (*) highlights the amino acid residue conservation in all FT homologs. (B) Evolutionary relationship of TFL1 homologs. (C) Expression pattern of ScFT1 of different tissues by semi-quantitative PCR, IL: apex-surrounding immature leaves; ML, mature leaves; AM, apical meristem; ML(F), mature leaves of mature flowering plants. (D) Amino acid sequences from different species were aligned using ClustalW, the evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. Bootstrap values from 1000 replications were used to assess the robustness of the trees. Accession numbers: BvFT1 (ADM92608.1), BvFT2 (ADM92610.1), NtFT1 (AFS17369.1), NtFT2 (AFS17370.1), NtFT3 (AFS17371.1), NtFT4 (AFS17372.1), FT (BAA77838.1), Hd3a (BAB61030.1), ZCN8 (ABX11010.1), ScFT1 (KJ496327).

Phylogenetic analysis of FT-like proteins showed that the FT-like floral repressors from tobacco clade together and the floral promoter NtFT4 clades with the FT-like floral promoters, FT and Hd3a (Figure 4D). As sugarcane and maize are more closely related to each other than to other species examined it is not unexpected that ScFT1 clades with maize ZCN8, but not to other FT-like proteins, such as FT and Hd3a. Despite the finding that ZCN8 does not clade with FT-like floral promoters, the strong association of ZCN8 with a maize flowering time QTL and its ability to complement an Arabidopsis ft mutant suggests that it acts as a floral promoter in maize (Lazakis et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2011). Similar to all PEBP family members, the ScFT1 gene consists of four exons and three introns, with similar exon sizes but largely varying the number of nucleotides in the introns (Figure 4B).

Expression analysis in sugarcane showed that ScFT1 transcript is present in mature leaves of vegetative phase plants, although it was expressed in immature leaves and SAM of the same plants. Interestingly, ScFT1 transcript was detected in mature leaves of flowering plants (Figure 4C), suggesting a possible role in post-floral transition plants.

Transgenic plants overexpressing ScFT1 delayed flowering and caused abnormal silique development

Sugarcane ScFT1 was over-expressed in Arabidopsis to test whether this FT-like candidate is involved in controlling flowering time. Four independent transgenic lines were selected for flowering time analysis and shown to over-express the transgene (Supplemental Figure 1B). Unexpectedly, in all cases ScFT1 over-expression resulted in late flowering plants, with an average range of 16.1–24.5 rosette leaves, compared to the 11.4 rosette leaves of Col-0 wild-type (Table 2). The most severe effect on flowering time was observed in ScFT1-3, which had a significantly higher transgene expression than the other three lines (Supplemental Figure 1B).

Table 2.

Flowering characteristics of four 35S::ScFT1 independent transgenic lines.

| Plant genotype | Days to flowering | Number of leaves | Number of plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Col-0 wild-type | 32 | 11.4 ± 0.54 | 5 |

| ScFT1-1 | 37 | 16.1 ± 0.87a | 10 |

| ScFT1-2 | 37 | 17.3 ± 2.16a | 10 |

| ScFT1-3 | 46 | 24.5 ± 1.84a | 9 |

| ScFT1-4 | 37 | 19.6 ± 1.41a | 10 |

Indicates statistically different from wild-type with p > 0.05 by student t-test.

In addition to later flowering, all ScFT1 over-expressing lines often exhibited defects in floral organ formation. Unlike ScTFL1 lines, where the latest flowering phenotype was associated with defects in reproductive structures, the ScFT1 over-expressing line with the most severe reproductive abnormalities was ScFT1-1, which consistently had a high number of sterile flowers and formed abnormally shorter siliques (Figure 5A). Furthermore, most siliques had abnormal development, leading to poor seed set and mostly sterile plants. In ScFT1 transgenic lines, open flowers did not self-fertilize and siliques did not develop from fertilized carpels, which may explain the shorter siliques (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Ectopic expression of ScFT1-1 affects flowering time and silique development. (A) Comparison of development timing of ScFT1-1 (right) with Col-0 wild-type plant (left). (B) Close-up at the siliques from Col-0 (left), ScFT1-1 flowers (middle), and abnormal siliques (right).

These results suggest that ScFT1 may be involved in meristem activities that control flowering time and production of fertile organs, although further analysis is required to understand the effects of ScFT1 overexpression in meristem development. Other studies have reported that loss of FT-like function caused meristem-associated abnormalities (Bohlenius et al., 2006; Shalit et al., 2009; Krieger et al., 2010; Danilevskaya et al., 2011; Navarro et al., 2011).

Yet to be characterized ScFT-like genes may be involved in sugarcane floral induction

ScFT1 is the only full-length FT-like candidate we were able to isolate from the sugarcane genome. Four other incomplete sequences were identified in the sugarcane EST database (SUCEST), which we designate ScFT2, ScFT3, ScFt4, and ScFT5. Of the candidates that were analyzed, ScFT2 is most closely related to FT-like candidates maize ZCN8 and ScFT1. The ScFT3 and ScFT4 putative homologs clade with all floral promoter FT-like genes, Hd3a, FT, and BvFT1 (Figure 6A), indicating that we cannot rule out the possibility that one or both of them may act as florigen in sugarcane. Functional characterization of these candidates will enlighten this hypothesis. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that ScFT3 and ScFT4 clade with floral promoters, given the high degree of similarity of segment B compared to other FT floral promoting proteins (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Sequence analysis of ScFT protein candidates with other FT homologs. (A) Amino acid sequences from different species were aligned to five ScFT-like candidates using ClustalW. (B) Phylogenetic tree of FT homologs. Bootstrap values from 1000 replications were used to assess the robustness of the tree. Sugarcane ScFT-like candidate genes are highlighted by a diamond symbol (♦) and FT homolog from related species are deposited at the Genbank database. A black line highlights segment (B). Accession numbers: BvFT1 (ADM92608.1), BvFT2 (ADM92610.1), NtFT1 (AFS17369.1), NtFT2 (AFS17370.1), NtFT3 (AFS17371.1), NtFT4 (AFS17372.1), FT (BAA77838.1), Hd3a (BAB61030.1), ZCN8 (ABX11010.1).

Discussion

ScTFL1 maintains meristem indeterminacy in arabidopsis, suggesting a similar role in sugarcane

Although extreme late flowering is a negative agronomic trait in many crops, it is of great advantage in commercial sugarcane plants, where a non-flowering phenotype is a highly desirable trait that is the objective of many sugarcane-breeding programs (Berding and Hurney, 2005; Van Heerden et al., 2010). Maintaining sugarcane plants in a vegetative state prevents the loss of sugar accumulation in the stalks that would result from precocious flowering, especially in the tropics where day-length is inductive for floral transition throughout the year.

As a first step in elucidating the molecular mechanisms that control flowering in sugarcane we isolated FT/TFL1 gene family homologs of key flowering time genes first characterized in Arabidopsis. Two of these genes, ScTFL1 and ScFT1, were analyzed for their role in flowering by ectopic expression in Arabidopsis. We have validated this technique previously by showing that over-expression of another monocot flowering gene, the maize FT-like gene ZCN8, had a dramatic effect on Arabidopsis flowering (Lazakis et al., 2011). Similarly ectopic expression of FT/TFL related genes have been demonstrated for diverse plant species (Jensen et al., 2001; Nakagawa et al., 2002; Mimida et al., 2009; Pin et al., 2010; Karlgren et al., 2011; Klintenas et al., 2012).

Late flowering was observed in Arabidopsis plants over-expressing ScTFL1. This suggests that ScTFL1 acts by extending the duration of growth phases and maintenance of the inflorescence meristem in sugarcane. The latest flowering ScTFL1 overexpressing plants also had abnormal floral organ structures, which may be due to an imbalance between TFL1 and AP1 expression. This leads to floral reversion to vegetative structures, triggering the appearance of floral buds inside the aerial rosettes, resulting in enhanced indeterminate growth. In wild-type plants, AP1 down-regulates TFL1 in floral meristems and, in turn, TFL1 maintains indeterminate growth of the vegetative center (Ratcliffe et al., 1999). Although complete inhibition of flowering has not been observed in any single mutants in Arabidopsis, this is not the case for double mutants. Floral transition is never completed in pennywise and pound-foolish (pny pnf) double mutants (Smith et al., 2004). Loss of both of these duplicate BELL homeobox genes results in ectopic TFL1 expression at high levels in the vasculature, the same site of FT expression. This indicates that ectopic overexpression of TFL1 can result in a non-flowering phenotype.

The altered architecture of the ScTFL1-41 is similar to that observed in the Arabidopsis late-flowering ecotype, Sy-0, which also has aerial rosettes formation in flowering stems (Grbic and Bleecker, 1996). Aerial rosette formation is often related to loss of floral meristem identity genes responsible for signal transduction of the AP1 gene, an integrator of all flowering pathways that determines floral organ formation. By the time AP1 is expressed, floral determination is initiated and plants continue to flower independent of environmental signals (Hempel et al., 1997). Grbic and Bleecker (1996) suggested that this phenotype is a result of the interaction of two main dominant genes, AERIAL ROSETTE (ART) and ENHANCER OF AERIAL ROSETTE (EAR). Mutant phenotypes of aerial rosette 1 (art1) are a consequence of a delay from the vegetative (V) to reproductive (R) phase transitions, resulting in the formation of a new type of metamer consisting of V1 → V2* → R* → R, in which aerial rosettes are formed by the V2* stage (Poduska et al., 2003). Similar to this, 35S::TFL1 plants also have a prolonged vegetative phase and produce aerial rosettes (Ratcliffe et al., 1998, 1999). Aerial rosette formation also was reported when another BELL gene, ATH1, was over-expressed in Arabidopsis (Proveniers et al., 2007).

Increased axillary branching of the ScTFL1 transgenic plants is similar to the effects observed when other TFL1 homologs are over-expressed in Arabidopsis. It was suggested that this phenotype may be a consequence of interaction of TFL1 with hormones, since plant hormones such as auxin, cytokinin and strigolactone play a role in the branching and outgrowth of plants (McSteen, 2009; Danilevskaya et al., 2010). The TFL1 protein complex was reported previously, and the external loop seems to be the site for co-repressors/co-activators to bind and trigger developmental responses. Nevertheless, these co-repressors/co-activators have not yet been identified (Taoka et al., 2013), raising the possibility that plant hormone activity could be connected to the mechanisms by which ScTFL1 results in the observed phenotypes.

Mechanisms of TFL1 function are less clear than that of FT; moreover TFL1 function may vary among annual and perennial plants. TFL1 was reported to act in an age-dependent flowering pathway in the perennial Arabis alpina. In these plants, AaTFL1 is responsible for the maintenance of vegetative growth of young plants, even under inductive conditions, preventing all axillary meristems from becoming determined. As the shoot ages, AaTFL1 sets an increasing flowering threshold and the plant is able to develop perennial traits (Wang et al., 2011). In perennial ryegrass, the TFL1 homolog LpTFL1 is up-regulated in the apex once the temperature and day-length increases, allowing for lateral branching, and consequently, the promotion of tillering (Jensen et al., 2001). It is possible that ScTFL1 acts in a similar manner in perennial sugarcane, perhaps explaining the expression of this gene in leaves surrounding the peripheral regions of the meristem of vegetatively growing plants. Further studies of the expression pattern of ScTFL1 at the shoot apex and surrounding developing leaves of mature flowering plants may provide insights about this possibility.

ScFT1 may control flowering time and inflorescence formation in sugarcane

Evolutionary analysis of the PEBP family suggests that FT-like and TFL1-like subfamilies arose from a common TFL1-like ancestor, and that the FT-like floral promoter evolved within the angiosperm clade (Karlgren et al., 2011; Klintenas et al., 2012). Therefore it is possible that floral repressor activity of FT-like genes persists among angiosperms, as has been reported for tobacco (Harig et al., 2012) and sugar beet (Pin et al., 2010).

The present work suggests that ScFT1 functions as a floral repressor in sugarcane. Strikingly, expression of ScFT1 varies under non-inductive and inductive conditions. Under non-inductive long-day conditions, ScFT1 is expressed in both immature leaves and the apical meristem region, but is not detected in mature leaves. Under inductive short day conditions, however, ScFT1 is expressed in mature leaves, which are the source of the florigen signal. Together with the late flowering phenotype observed in the overexpressing Arabidopsis lines, this could indicate that ScFT1 is associated with an anti-florigen signal that originates in mature leaves under floral inductive conditions to counter-balance the florigen signal.

The effect of ScFT1 overexpression on silique development is similar to that observed in Arabidopsis dyt1 mutants; DYSFUNCTIONAL TAPETUM1 (DYT1) is involved in tapetum differentiation and function and, without functional DYT1, normal anther development is interrupted, generating plants with very small siliques (Zhang et al., 2006). BEL1 and SHORT INTEGUMENT (SIN1) control ovule development in Arabidopsis as bel1 mutants transform ovule integuments into carpels due to ectopic expression of AGAMOUS (AG) in these tissues (Ray et al., 1994). Alterations of bel1 mutants include increased axillary buds, delayed senescence and short abnormal siliques formation, similar to what we observe in ScFT1 plants (Robinson-Beers et al., 1992). Loss of SIN1 also affects flowering time, resulting in an increased number of rosette leaves and coflorescence branches. SIN1 is epistatic to TFL1 and may act in an independent pathway to suppress, at least in part, the tfl1 phenotype (Ray et al., 1996).

All FT-like proteins involved in floral promotion have a conserved segment B region encoded in the fourth exon that is essential for these homologs to act as florigens in diverse plant species (Ahn et al., 2006; Pin et al., 2010; Harig et al., 2012). Segment B of ScFT1 varies in three amino acid residues compared to the FT and Hd3a floral proteins. In sugar beet variation of three amino acids in segment B of two FT-like proteins is sufficient for them to act antagonistically (Pin et al., 2010). Comparison of partial sequences of several ScFT-like genes from the sugarcane EST database (SUCEST) indicates that ScFT3 and ScFT4 candidates may be involved in the floral promotion, considering the sequence conservation and phylogenetic relationship to FT-like homolog subfamilies. Full-length transcripts need to be characterized to evaluate the effect of sequence plasticity and divergence of functions of sugarcane FT-like genes.

Recent discoveries suggest that FT-like proteins act not only as floral repressors but also in diverse developmental events, such as potato tuberization (Navarro et al., 2011), seasonal control of growth cessation in poplar trees (Bohlenius et al., 2006), termination of meristem growth and fruit yield in tomato (Shalit et al., 2009; Krieger et al., 2010), plant architecture in maize (Danilevskaya et al., 2011), and stomatal control in Arabidopsis (Kinoshita et al., 2011). Together these different activities raise a fundamental question about whether FT-like proteins function as versatile mobile signals orchestrating diverse processes in plant development rather than solely acting as a florigen (Taoka et al., 2013).

Author contributions

Carla P. Coelho and Joseph Colasanti designed the experiments and organized the manuscript. Carla P. Coelho and Mark A. A. Minow performed the experiments. Antonio Chalfun-Júnior and Joseph Colasanti edited the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Mucci and Tannis Slimmon for the expert plant care provided at the Phytotron Facility of the University of Guelph, as well as The Programa de Doutorado Sanduiche no Exterior (PDSE—CAPES) and the National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) who provided doctoral scholarships for Carla Coelho. Research in JCs lab is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fpls.2014.00221/abstract

Expression analysis of the transgenes in Arabidopsis independent lines. (A) ScTFL1 expression relative to Arabidopsis ACTIN8 expression in the lines ScTFL1-5, ScTFL1-6, ScTFL1-11, and ScTFL1-41. (B) ScFT1 expression relative to ACTIN8 expression in the lines ScFT1-1, ScFT1-2, ScFT3, and ScFT4. Error bars denote relative quantity maximum and minimum values from triplicate biological samples, with each sample a pool of five plantlets.

Ectopic ScTFL1 expression affects flowering in four independent lines of transgenic Arabidopsis, under long-day conditions after 43 days. (A) 35S::ScTLF1-5; (B) 35S::ScTFL1-6; (C) 35S::ScTFL1-11; (D) 35S::ScTFL1-41. Transgenic plants are on the right plants and Col-0 wild-type plants are on the left in all panels.

References

- Abe M., Kobayashi Y., Yamamoto S., Daimon Y., Yamaguchi A., Ikeda Y., et al. (2005). FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309, 1052–1056 10.1126/science.1115983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abràmoff M. D., Magalhães P. J., Ram S. J. (2004). Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Intern. 11, 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J. H., Miller D., Winter V. J., Banfield M. J., Lee J. H., Yoo S. Y., et al. (2006). A divergent external loop confers antagonistic activity on floral regulators FT and TFL1. Embo J. 25, 605–614 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albani M. C., Coupland G. (2010). Comparative analysis of flowering in annual and perennial plants, in Plant Development, ed Timmermans M. C. P. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 323–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H. L., Roussot C., Suarez-Lopez P., Corbesler L., Vincent C., Pineiro M., et al. (2004). CONSTANS acts in the phloem to regulate a systemic signal that induces photoperiodic flowering of Arabidopsis. Development 131, 3615–3626 10.1242/dev.01231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfield M. J., Barker J. J., Perry A. C. F., Brady R. L. (1998). Function from structure? The crystal structure of human phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein suggests a role in membrane signal transduction. Structure 6, 1245–1254 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00125-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berding N., Hurney A. P. (2005). Flowering and lodging, physiological-based traits affecting cane and sugar yield - What do we know of their control mechanisms and how do we manage them? Field Crops Res. 92, 261–275 10.1016/j.fcr.2005.01.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergonzi S., Albani M. C., Van Themaat E. V. L., Nordstrom K. J. V., Wang R. H., Schneeberger K., et al. (2013). Mechanisms of age-dependent response to winter temperature in perennial flowering of arabis alpina. Science 340, 1094–1097 10.1126/science.1234116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman B. K., Rasmussen D. A., Strasburg J. L., Raduski A. R., Burke J. M., Knapp S. J., et al. (2011). Contributions of flowering time genes to sunflower domestication and improvement. Genetics 187, 271–287 10.1534/genetics.110.121327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlenius H., Huang T., Charbonnel-Campaa L., Brunner A. M., Jansson S., Strauss S. H., et al. (2006). CO/FT regulatory module controls timing of flowering and seasonal growth cessation in trees. Science 312, 1040–1043 10.1126/science.1126038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. L., Alvarez J., Weigel D., Meyerowitz E. M., Smyth D. R. (1993). Control of flower development in arabidopsis-thaliana by apetala1 and interacting genes. Development 119, 721–743 [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D., Ratcliffe O., Vincent C., Carpenter R., Coen E. (1997). Inflorescence commitment and architecture in Arabidopsis. Science 275, 80–83 10.1126/science.275.5296.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardon F., Damerval C. (2005). Phylogenomic analysis of the PEBP gene family in cereals. J. Mol. Evol. 61, 579–590 10.1007/s00239-004-0179-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho C. P., Costa Netto A. P., Colasanti J., Chalfun-Junior A. (2013). A proposed model for the flowering signaling pathway of sugarcane under photoperiodic control. Genet. Mol. Res. 12, 1347–1359 10.4238/2013.April.25.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti J., Yuan Z., Sundaresan V. (1998). The indeterminate gene encodes a zinc finger protein and regulates a leaf-generated signal required for the transition to flowering in maize. Cell 93, 593–603 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81188-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti L., Bradley D. (2007). TERMINAL FLOWER1 is a mobile signal controlling Arabidopsis architecture. Plant Cell 19, 767–778 10.1105/tpc.106.049767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L., Vincent C., Jang S. H., Fornara F., Fan Q. Z., Searle I., et al. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316, 1030–1033 10.1126/science.1141752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilevskaya O. N., Meng X., Ananiev E. V. (2010). Concerted modification of flowering time and inflorescence architecture by ectopic expression of TFL1-like genes in maize. Plant Physiol. 153, 238–251 10.1104/pp.110.154211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilevskaya O. N., Meng X., McGonigle B., Muszyski M. G. (2011). Beyond flowering time. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1267–1270 10.4161/psb.6.9.16423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence-limits on phylogenies - an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornara F., De Montaigu A., Coupland G. (2010). SnapShot: control of Flowering in Arabidopsis. Cell 141, 550–550.e2 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grbic V., Bleecker A. B. (1996). Altered body plan is conferred on Arabidopsis plants carrying dominant alleles of two genes. Development 122, 2395–2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 [Google Scholar]

- Hanano S., Goto K. (2011). Arabidopsis TERMINAL FLOWER1 is involved in the regulation of flowering time and inflorescence development through transcriptional repression. Plant Cell 23, 3172–3184 10.1105/tpc.111.088641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y., Money T., Bradley D. (2005). A single amino acid converts a repressor to an activator of flowering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7748–7753 10.1073/pnas.0500932102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harig L., Beinecke F. A., Oltmanns J., Muth J., Muller O., Ruping B., et al. (2012). Proteins from the FLOWERING LOCUS T-like subclade of the PEBP family act antagonistically to regulate floral initiation in tobacco. Plant J. 72, 908–921 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht V., Foucher F., Ferrandiz C., Macknight R., Navarro C., Morin J., et al. (2005). Conservation of Arabidopsis flowering genes in model legumes. Plant Physiol. 137, 1420–1434 10.1104/pp.104.057018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel F. D., Weigel D., Mandel M. A., Ditta G., Zambryski P. C., Feldman L. J., et al. (1997). Floral determination and expression of floral regulatory genes in Arabidopsis. Development 124, 3845–3853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huala E., Sussex I. M. (1992). Leafy interacts with floral homeotic genes to regulate arabidopsis floral development. Plant Cell 4, 901–913 10.1105/tpc.4.8.901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi T., Kay S. A. (2006). Photoperiodic control of flowering: not only by coincidence. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 550–558 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish V. F., Sussex I. M. (1990). Function of the APETALA1 gene in Arabidopsis floral development. Plant Cell 2, 741–753 10.1105/tpc.2.8.741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger K. E., Pullen N., Lamzin S., Morris R. J., Wigge P. A. (2013). Interlocking Feedback loops govern the dynamic behavior of the floral transition in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 820–833 10.1105/tpc.113.109355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger K. E., Wigge P. A. (2007). FT protein acts as a long-range signal in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 17, 1050–1054 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen C. S., Salchert K., Nielsen K. K. (2001). A TERMINAL FLOWER1-Like gene from perennial ryegrass involved in floral transition and axillary meristem identity. Plant Physiol. 125, 1517–1528 10.1104/pp.125.3.1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlgren A., Gyllenstrand N., Kallman T., Sundstrom J. F., Moore D., Lascoux M., et al. (2011). Evolution of the PEBP gene family in plants: functional diversification in seed plant evolution. Plant Physiol. 156, 1967–1977 10.1104/pp.111.176206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempin S. A., Savidge B., Yanofsky M. F. (1995). Molecular-basis of the cauliflower phenotype in arabidopsis. Science 267, 522–525 10.1126/science.7824951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., Ono N., Hayashi Y., Morimoto S., Nakamura S., Soda M., et al. (2011). FLOWERING LOCUS T regulates stomatal opening. Curr. Biol. 21, 1232–1238 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klintenas M., Pin P. A., Benlloch R., Ingvarsson P. K., Nilsson O. (2012). Analysis of conifer FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER1-like genes provides evidence for dramatic biochemical evolution in the angiosperm FT lineage. New Phytol. 196, 1260–1273 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S., Takahashi Y., Kobayashi Y., Monna L., Sasaki T., Araki T., et al. (2002). Hd3a, a rice ortholog of the Arabidopsis FT gene, promotes transition to flowering downstream of Hd1 under short-day conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 1096–1105 10.1093/pcp/pcf156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger U., Lippman Z. B., Zamir D. (2010). The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 42, 459–U138 10.1038/ng.550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazakis C. M., Coneva V., Colasanti J. (2011). ZCN8 encodes a potential orthologue of Arabidopsis FT florigen that integrates both endogenous and photoperiod flowering signals in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 4833–4842 10.1093/jxb/err129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifschitz E., Eviatar T., Rozman A., Shalit A., Goldshmidt A., Amsellem Z., et al. (2006). The tomato FT ortholog triggers systemic signals that regulate growth and flowering and substitute for diverse environmental stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6398–6403 10.1073/pnas.0601620103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. K., Belanger H., Lee Y. J., Varkonyi-Gasic E., Taoka K. I., Miura E., et al. (2007). FLOWERING LOCUS T protein may act as the long-distance florigenic signal in the cucurbits. Plant Cell 19, 1488–1506 10.1105/tpc.107.051920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel M. A., Gustafsonbrown C., Savidge B., Yanofsky M. F. (1992). Molecular characterization of the arabidopsis floral homeotic gene apetala1. Nature 360, 273–277 10.1038/360273a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu J., Warthmann N., Kuttner F., Schmid M. (2007). Export of FT protein from phloem companion cells is sufficient for floral induction in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 17, 1055–1060 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro-Herrera M., Wang X., Barbier H., Brutnell T. P., Devos K. M., Doust A. N. (2013). Genetic control and comparative genomic analysis of flowering time in setaria (Poaceae). G3 (Bethesda). 3, 283–295 10.1534/g3.112.005207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSteen P. (2009). Hormonal regulation of branching in grasses. Plant Physiol. 149, 46–55 10.1104/pp.108.129056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Muszynski M. G., Danilevskaya O. N. (2011). The FT-Like ZCN8 gene functions as a floral activator and is involved in photoperiod sensitivity in maize. Plant Cell 23, 942–960 10.1105/tpc.110.081406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimida N., Kotoda N., Ueda T., Igarashi M., Hatsuyama Y., Iwanami H., et al. (2009). Four TFL1CEN-like genes on distinct linkage groups show different expression patterns to regulate vegetative and reproductive development in apple (malusdomestica borkh.). Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 394–412 10.1093/pcp/pcp001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M., Shimamoto K., Kyozuka J. (2002). Overexpression of RCN1 and RCN2, rice TERMINAL FLOWER 1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs, confers delay of phase transition and altered panicle morphology in rice. Plant J. 29, 743–750 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro C., Abelenda J. A., Cruz-Oro E., Cuellar C. A., Tamaki S., Silva J., et al. (2011). Control of flowering and storage organ formation in potato by FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nature 478, 119–U132 10.1038/nature10431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. (2001). A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin P. A., Benlloch R., Bonnet D., Wremerth-Weich E., Kraft T., Gielen J. J. L., et al. (2010). An antagonistic pair of FT homologs mediates the control of flowering time in sugar beet. Science 330, 1397–1400 10.1126/science.1197004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pnueli L., Gutfinger T., Hareven D., Ben-Naim O., Ron N., Adir N., et al. (2001). Tomato SP-interacting proteins define a conserved signaling system that regulates shoot architecture and flowering. Plant Cell 13, 2687–2702 10.1105/tpc.13.12.2687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poduska B., Humphrey T., Redweik A., Grbic V. (2003). The synergistic activation of FLOWERING LOCUS C by FRIGIDA and a new flowering gene AERIAL ROSETTE 1 underlies a novel morphology in Arabidopsis. Genetics 163, 1457–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proveniers M., Rutjens B., Brand M., Smeekens S. (2007). The Arabidopsis TALE homeobox gene ATH1 controls floral competency through positive regulation of FLC. Plant J. 52, 899–913 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe O. J., Amaya I., Vincent C. A., Rothstein S., Carpenter R., Coen E. S., et al. (1998). A common mechanism controls the life cycle and architecture of plants. Development 125, 1609–1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe O. J., Bradley D. J., Coen E. S. (1999). Separation of shoot and floral identity in Arabidopsis. Development 126, 1109–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A., Lang J. D., Golden T., Ray S. (1996). SHORT INTEGUMENT (SIN1), a gene required for ovule development in Arabidopsis, also controls flowering time. Development 122, 2631–2638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A., Robinson-Beers K., Ray S., Baker S. C., Lang J. D., Preuss D., et al. (1994). Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene bell (bel1) controls ovule development through negative regulation of agamous gene (AG). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5761–5765 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Beers K., Pruitt R. E., Gasser C. S. (1992). Ovule development in wild-type arabidopsis and 2 female-sterile mutants. Plant Cell 4, 1237–1249 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N., Nei M. (1987). The neighbor-joinig method - a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz E. A., Haughn G. W. (1991). Leafy, a homeotic gene that regulates inflorescence development in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 3, 771–781 10.1105/tpc.3.8.771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz E. A., Haughn G. W. (1993). Genetic-analysis of the floral initiation process (flip) in arabidopsis. Development 119, 745–765 [Google Scholar]

- Shalit A., Rozman A., Goldshmidt A., Alvarez J. P., Bowman J. L., Eshed Y., et al. (2009). The flowering hormone florigen functions as a general systemic regulator of growth and termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8392–8397 10.1073/pnas.0810810106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon S., Meekswagner D. R. (1991). A mutation in the arabidopsis TFL1 gene affects inflorescence meristem development. Plant Cell 3, 877–892 10.1105/tpc.3.9.877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon S., Meekswagner D. R. (1993). Genetic interactions that regulate inflorescence development in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5, 639–655 10.1105/tpc.5.6.639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. M. S., Campbell B. C., Hake S. (2004). Competence to respond to floral inductive signals requires the homeobox genes PENNYWISE and POUND-FOOLISH. Curr. Biol. 14, 812–817 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada S., Goto K. (2003). TERMINAL FLOWER2, an Arabidopsis homolog of HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN1, counteracts the activation of FLOWERING LOCUS T by CONSTANS in the vascular tissues of leaves to regulate flowering time. Plant Cell 15, 2856–2865 10.1105/tpc.016345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki S., Matsuo S., Wong H. L., Yokoi S., Shimamoto K. (2007). Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316, 1033–1036 10.1126/science.1141753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007). MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka K., Ohki I., Tsuji H., Furuita K., Hayashi K., Yanase T., et al. (2011). 14-3-3 proteins act as intracellular receptors for rice Hd3a florigen. Nature 476, 332–U397 10.1038/nature10272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka K., Ohki I., Tsuji H., Kojima C., Shimamoto K. (2013). Structure and function of florigen and the receptor complex. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 287–294 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A., Massiah A. J., Thomas B. (2010). Conservation of Arabidopsis thaliana photoperiodic flowering time genes in onion (Allium cepa L.). Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1638–1647 10.1093/pcp/pcq120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heerden P. D. R., Donaldson R. A., Watt D. A., Singels A. (2010). Biomass accumulation in sugarcane: unravelling the factors underpinning reduced growth phenomena. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 2877–2887 10.1093/jxb/erq144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vettore A. L., Da Silva F. R., Kemper E. L., Arruda P. (2001). The libraries that made SUCEST. Genet. Mol. Biol. 24, 1–7 10.1590/S1415-47572001000100002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. H., Albani M. C., Vincent C., Bergonzi S., Luan M., Bai Y., et al. (2011). Aa TFL1 confers an age-dependent response to vernalization in perennial arabis alpina. Plant Cell 23, 1307–1321 10.1105/tpc.111.083451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D., Alvarez J., Smyth D. R., Yanofsky M. F., Meyerowitz E. M. (1992). Leafy controls floral meristem identity in arabidopsis. Cell 69, 843–859 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90295-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge P. A., Kim M. C., Jaeger K. E., Busch W., Schmid M., Lohmann J. U., et al. (2005). Integration of spatial and temporal information during floral induction in Arabidopsis. Science 309, 1056–1059 10.1126/science.1114358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S. J., Chung K. S., Jung S. H., Yoo S. Y., Lee J. S., Ahn J. H. (2010). BROTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (BFT) has TFL1-like activity and functions redundantly with TFL1 in inflorescence meristem development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 63, 241–253 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Sun Y. J., Timofejeva L., Chen C. B., Grossniklaus U., Ma H. (2006). Regulation of Arabidopsis tapetum development and function by dysfunctional tapetum1 (dyt1) encoding a putative bHLH transcription factor. Development 133, 3085–3095 10.1242/dev.02463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression analysis of the transgenes in Arabidopsis independent lines. (A) ScTFL1 expression relative to Arabidopsis ACTIN8 expression in the lines ScTFL1-5, ScTFL1-6, ScTFL1-11, and ScTFL1-41. (B) ScFT1 expression relative to ACTIN8 expression in the lines ScFT1-1, ScFT1-2, ScFT3, and ScFT4. Error bars denote relative quantity maximum and minimum values from triplicate biological samples, with each sample a pool of five plantlets.

Ectopic ScTFL1 expression affects flowering in four independent lines of transgenic Arabidopsis, under long-day conditions after 43 days. (A) 35S::ScTLF1-5; (B) 35S::ScTFL1-6; (C) 35S::ScTFL1-11; (D) 35S::ScTFL1-41. Transgenic plants are on the right plants and Col-0 wild-type plants are on the left in all panels.