Abstract

The phytotoxic fungal polyketides lasiodiplodin and resorcylide inhibit human blood coagulation factor XIIIa, mineralocorticoid receptors, and prostaglandin biosynthesis. These secondary metabolites belong to the 12-membered resorcylic acid lactone (RAL12) subclass of the benzenediol lactone (BDL) family. Identification of genomic loci for the biosynthesis of lasiodiplodin from Lasiodiplodia theobromae and resorcylide from Acremonium zeae revealed collaborating iterative polyketide synthase (iPKS) pairs whose efficient heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae provided a convenient access to the RAL12 scaffolds desmethyl-lasiodiplodin and trans-resorcylide, respectively. Lasiodiplodin production was reconstituted in the heterologous host by co-expressing an O-methyltransferase also encoded in the lasiodiplodin cluster, while a glutathione-S-transferase was found not to be necessary for heterologous production. Clarification of the biogenesis of known resorcylide congeners in the heterologous host helped to disentangle the roles that biosynthetic irregularities and chemical interconversions play in generating chemical diversity. Observation of 14-membered RAL homologues during in vivo heterologous biosynthesis of RAL12 metabolites revealed “stuttering” by fungal iPKSs. The close global and domain-level sequence similarities of the orthologous BDL synthases across different structural subclasses implicate repeated horizontal gene transfers and/or cluster losses in different fungal lineages. The absence of straightforward correlations between enzyme sequences and product structural features (the size of the macrocycle, the conformation of the exocyclic methyl group, or the extent of reduction by the hrPKS) suggest that BDL structural variety is the result of a select few mutations in key active site cavity positions.

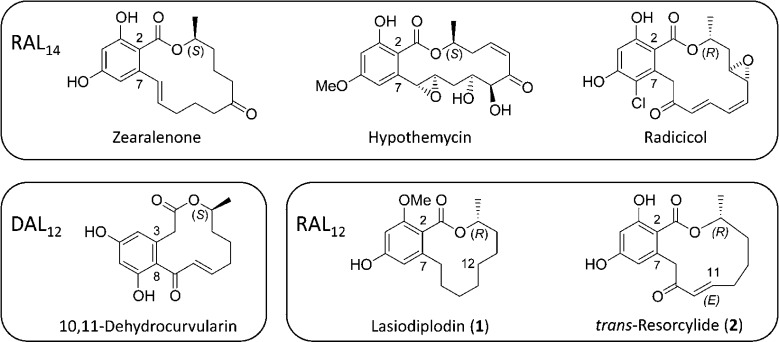

Benzenediol lactones (BDLs) are a growing class of fungal polyketide secondary metabolites defined by a 1,3-benzenediol moiety bridged by a macrocyclic lactone ring.1 The intramolecular aldol condensation that forms the benzenediol ring of BDLs may occur between C-2 and C-7 to yield resorcylic acid lactones (RALs) or between C-8 and C-3 to produce dihydroxyphenylacetic acid lactones (DALs).2,3 The best studied BDLs are RALs with a 14-membered macrocyclic ring (RAL14) such as zearalenone, hypothemycin, and radicicol and DALs with a 12-membered ring (DAL12) like 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (Figure 1). These BDLs are rich pharmacophores with an astonishing range of biological activities, including receptor agonist, mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitory, anti-inflammatory, and heat shock response and immune system modulatory activities.4,5

Figure 1.

Resorcylic acid and dihydroxyphenylacetic acid lactones.

The scaffolds of these fungal polyketides are biosynthesized by iterative polyketide synthases (iPKSs). These enzymes catalyze recursive, decarboxylative Claisen condensations of malonyl-CoA precursors to produce linear poly-β-ketoacyl intermediates using a single core set of ketoacyl synthase (KS), acyl transferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains. Further maturation of the polyketide chain requires additional domains. BDL biosynthesis initiates with the assembly of a variably reduced linear polyketide intermediate on a highly reducing iPKS (hrPKS). In addition to the core set of domains, hrPKSs feature ketoacyl reductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoyl reductase (ER) domains. These domains catalyze the formation of carbonyl, alcohol, alkene, or alkane functionalities by reducing the nascent β-ketones of the growing polyketide chain after each condensation, executing a cryptic biosynthetic program.6 The polyketide product of the hrPKS is directly transferred to a second, nonreducing iPKS (nrPKS) by the starter AT (SAT) domain of the nrPKS.6 After further elongations of the advanced starter unit without reduction, the product template (PT) domain of the nrPKS directs first ring closure by regiospecific aldol condensation. This condensation yields a resorcylic acid moiety (F-type folding, C2–C7 register) or a dihydroxyphenylacetic acid group (S-type folding, C8–C3 register).7,8 Finally, the C-terminal thioesterase (TE) domain of the nrPKS catalyzes product release by using an alcohol functionality of the polyketide chain as the nucleophile for the formation of the BDL macrolactone. Alternative nucleophiles may include an intramolecular enol to yield α-pyrones or water or alcohols from the media to form acyl resorcylic acids, acyl dihydroxyphenylacetic acids, and their esters.9,10 Thus, in contrast to most fungal polyketides that are assembled by a single iPKS, the biosynthesis of BDLs involves a collaborating hrPKS-nrPKS pair acting in sequence, forming a quasi-modular BDL synthase system.11−14 iPKSs that produce the RAL14 and DAL12 subclass of BDLs have been characterized in the producer fungi by gene disruptions11,12 and reconstituted both in vivo by heterologous expression in yeast and in vitro using isolated recombinant iPKS enzymes.13,15,16 However, the biosynthesis of the 12-membered RAL (RAL12) subclass of BDLs has not been characterized up till now, despite the important biological activities of these compounds and their potentially interesting biosynthetic mechanisms.

Among RAL12, lasiodiplodin (Figure 1) and its congeners (12-, 13- or 14-hydroxy-, 13-oxo-, and 3-O-desmethyl-lasiodiplodin) have been isolated from the tropical/subtropical plant pathogen Lasiodiplodia theobromae (syns. Botryodiplodia theobromae and Diplodia gossypina, teleomorph Botryosphaeria rodina).17−19 Lasiodiplodins have also been identified from Syncephalastrum racemosum(20) and various plant biomass sources potentially inhabited by fungi.21 Lasiodiplodin congeners are plant growth regulators that induce potato microtuber formation.17,18 They are also phytotoxic by blocking the electron transport chain in thylakoids at multiple targets that are different from those of current herbicides.19 In addition to its phytotoxic activities, 3-O-desmethyl-lasiodiplodin inhibits prostaglandin biosynthesis21 and displays nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor inhibitory activity.22 Lasiodiplodin has been reported to have antileukemic activities.23

Another RAL12, trans-resorcylide (Figure 1), and its congeners (cis-resorcylide, 11-hydorxyresorcylide enantiomers, and their methyl esters) have been isolated from Penicillium spp.,24Pyrenophora teres,25 and Acremonium (Sarocladium) zeae.26 Resorcylides are phytotoxic as demonstrated in leaf-puncture wound assays and inhibit seedling root elongation.24−26trans-Resorcylide (but not the cis isomer) is a specific inhibitor of 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase, a key enzyme in prostaglandin catabolism.27cis-R-(−)-Resorcylide specifically inhibits blood coagulation factor XIIIa and may be advantageous to enhance fibrinolysis and resolve blood clots.28

The polyketide origin and the intermediacy of 9-hydroxydecanoic acid in the biosynthesis of lasiodiplodins have been demonstrated by feeding labeled precursors to L. theobromae.29 Moreover, hydroxylation at the C-11 position in 11-hydroxylasiodiplodin was shown to occur after the completion of lasiodiplodin assembly on the iPKS. Fittingly, 7,9-dihydroxydecanoic acid was not utilized as a precursor by the producer fungus.29

In this work, we have cloned and sequenced the lasiodiplodin biosynthetic cluster from L. theobromae NBRC 31059 and the trans-resorcylide biosynthetic locus from Acremonium zeae NRRL 45893. We reconstituted the production of trans-resorcylide and its congeners and lasiodiplodin and some of its congeners in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by heterologous expression of the collaborating hrPKS-nrPKS gene pairs and tailoring enzymes if necessary. We have also isolated minor lasiodiplodin and resorcylide congeners revealing in vivo stuttering of iterative hrPKS and nrPKS enzymes in heterologous expression systems.

Results and Discussion

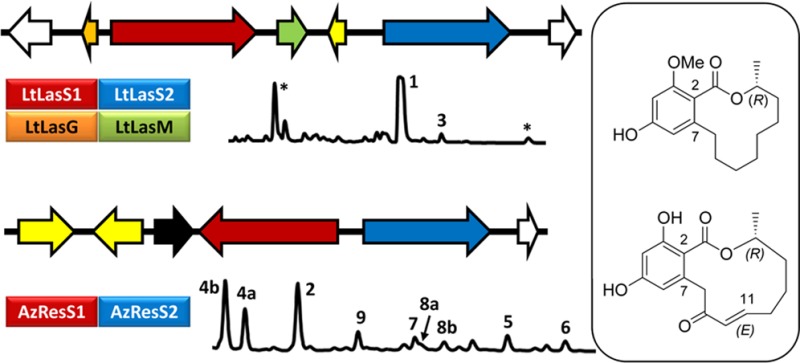

Isolation of the Lasiodiplodin and Resorcylide Biosynthetic Loci

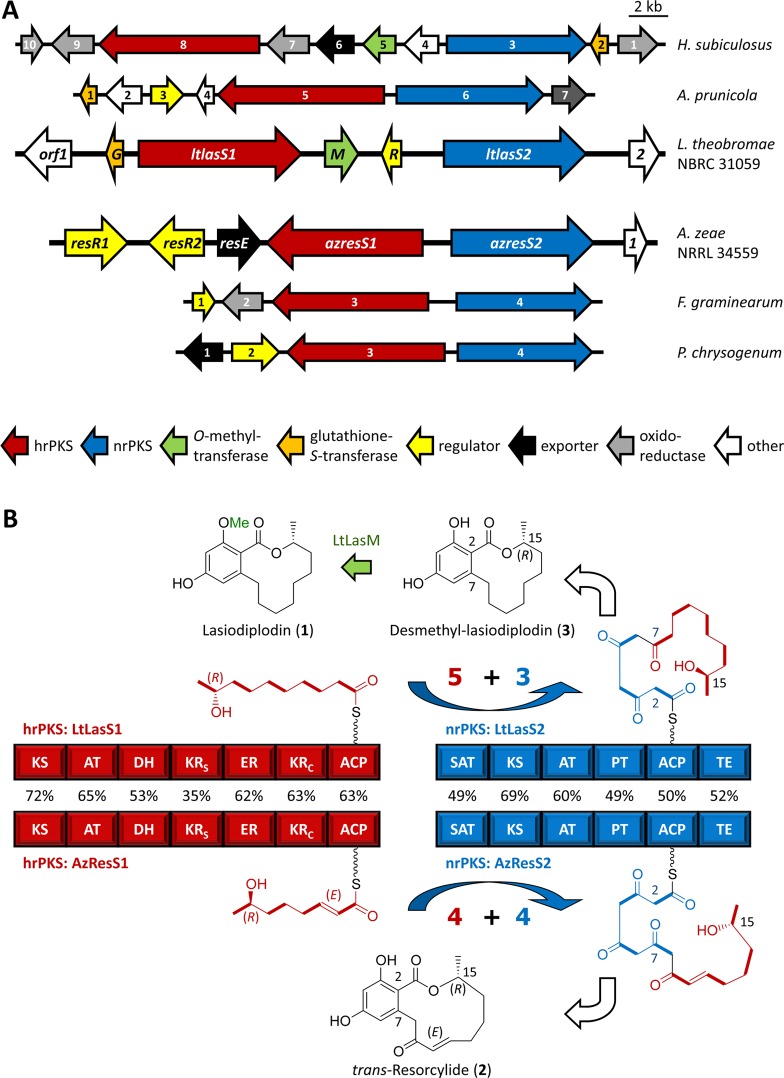

On the basis of established precedents for RAL14 and DAL12 production in fungi,11−14 we hypothesized that the biosynthesis of the RAL12 phytotoxins lasiodiplodin and resorcylide may involve collaborating iPKSs. In the absence of genome sequences for any RAL12 producers, we utilized our previously described PCR-based strategy14 to clone the lasiodiplodin and the resorcylide biosynthetic gene clusters. The resulting 30.1-kb (L. theobromae) and 28.4-kb (A. zeae) genomic loci encode putative proteins for one hrPKS-nrPKS pair each (LtLasS1-LtLasS2 and AzResS1-AzResS2, respectively, Figure 2A, Supplementary Table S2). The predicted lasiodiplodin cluster also features genes for a deduced O-methyltransferase (LtLasM), a putative glutathione-S-transferase (LtLasG), and a basic region leucine zipper domain family protein (LtLasR, Figure 2A, Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Results). In addition to the iPKSs, the resorcylide cluster also encodes a predicted major facilitator superfamily transporter (AzResE) and a pair of GAL4-like transcriptional regulators (AzResR1 and AzResR2, Figure 2A, Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Results). The predicted protein products of the surrounding genes of the two loci play no apparent roles in lasiodiplodin or resorcylide biosynthesis.

Figure 2.

Biosynthesis of BDLs. (A) Biosynthetic loci for lasiodiplodin from L. theobromae, trans-resorcylide from A. zeae, hypothemycin from H. subiculosus, zearalenone from F. graminearum, and orphan BDL biosynthetic loci from A. prunicola and P. chrysogenum. (B) Models for lasiodiplodin and trans-resorcylide biosynthesis. 5 + 3 and 4 + 4 indicate the number of malonate-derived C2 units (C–C bonds shown in bold) inserted by the hrPKS vs the nrPKS (“division of labor” or “split” by the collaborating iPKSs). Percentages show protein sequence identities for the indicated domains. KRS, ketoreductase structural subdomain; KRC, ketoreductase catalytic subdomain. For detailed annotations, see Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

The sequenced lasiodiplodin and resorcylide loci show no synteny with the complete genomes of the closest relatives of the producer fungi in the JGI MycoCosm or with BDL clusters in GenBank whose iPKSs display the highest identities to LtLasS and AzResS (Figure 2A, Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Nevertheless, orthologous iPKS pairs are present in these fungi in different genomic contexts. Fusarium graminearum and Hypomyces subiculosus are the producers of the known RAL14 zearalenone and hypothemycin, respectively.11,13 Although Aplosporella prunicola and Penicillium chrysogenum are not known to produce BDLs, their orphan BDL loci are predicted here to encode the biosynthesis of RALs.2

Heterologous Production of Desmethyl-lasiodiplodin and trans-Resorcylide

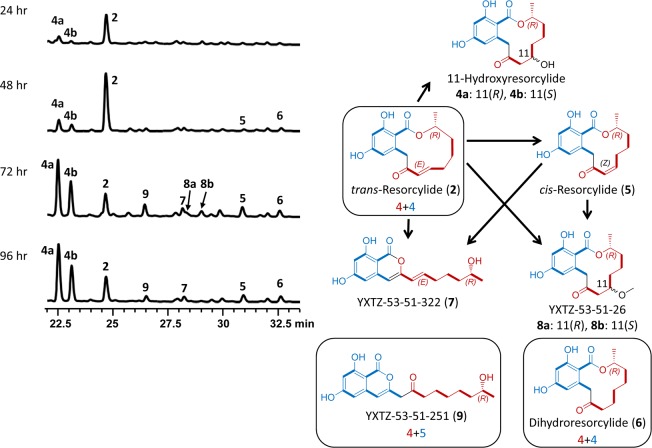

To establish cluster identity in the absence of available transformation systems for L. theobromae and A. zeae, heterologous production of lasiodiplodin and resorcylide was attempted.13,15,16,30 Thus, intron-less versions of the ltlasS1 and the ltlasS2 genes on one hand and those of the azresS1 and azresS2 on the other were introduced into S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA using YEpADH2p-derived expression vectors.14,16,31 The expected RAL12 products, desmethyl-lasiodiplodin (3) and trans-resorcylide (2) were produced in good yields by the recombinant strains (isolated yields: 10 mg/L for 3 and 8 mg/L for 2) (Figures 3 and 4). Minor BDL and isocoumarin products were also observed in both fermentations (see below).

Figure 3.

Reconstitution of lasiodiplodin biosynthesis in vivo. Product profiles (HPLC traces recorded at 300 nm) of S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA31 co-transformed with the genes for the indicated L. theobromae proteins. ∗, yeast metabolites unrelated to the iPKS products.

Figure 4.

Time-course analysis and interconversion of resorcylide congeners. Product profiles (HPLC traces recorded at 300 nm) of S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA31 co-transformed with azresS1 and azresS2 and induced for BDL production for the indicated amount of time.

In the absence of their hrPKS partners, heterologous hosts expressing BDL nrPKSs have been observed to produce acyl resorcylic or acyl dihydroxyphenylacetic acids by the chance utilization of various short chain fatty acyl thioesters.10,14,32 However, we have detected no such products in fermentations with S. cerevisiae strains expressing LtLasS2 or AzResS2 alone (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S1). Supplementation of these cultures with various short chain (C6–C12) fatty acids did not lead to the production of polyketides either. The lack of utilization of host-derived or supplemented fatty acids may be due to the more stringent substrate selectivity of these nrPKSs or, in the case of the fed substrates, excessive catabolism or a failure in uptake/compartmentalization by the yeast host.

Comparative Bioinformatic and Functional Analysis of the RAL12 iPKSs

The predicted LtLasS1 and AzResS1 enzymes are orthologous (Figure 2B) and share identical domain composition (KS-AT-DH-KRS-ER-KRC-ACP) with each other and the characterized BDL hrPKSs.11−14 These hrPKSs synthesize the starter acyl chains whose lengths determine the sizes of the bridging macrocycles of BDLs, while their variably reduced β-carbons dictate the shape and reactivity of these macrolactones. AzResS1 is expected to yield the tetraketide 7(R)-hydroxyoct-2(E)-enoic acid (Figure 2B), the C-7 enantiomer of the tetraketide biosynthesized by the dehydrocurvularin hrPKS AtCurS1.14 LtLasS1 is predicted to produce the pentaketide 9(R)-hydroxydecanoic acid, a reduced analogue of the radicicol/monocillin II pentaketide advanced starter unit.12,16 These hydroxycarboxylic acid products remain parked on the hrPKS as acyl-ACP thioesters pending transfer to the BDL nrPKS,6 with any acids released by infrequent spontaneous hydrolysis expected to be catabolized by the host. Accordingly, expression of LtLasS1 or AzResS1 in S. cerevisiae without their cognate nrPKS partners did not yield any detectable shunt metabolites (results not shown).

While the LtLasS1 and AzResS1 DH domains are programmed not to reduce the β-hydroxy moiety at the diketide stage, the KR domains are expected to be active after each extension step. This program yields a secondary alcohol at the penultimate carbon of the polyketide chain that will be used by the TE domain of the nrPKS for macrolactone closure. The stereochemical outcome of the KR-catalyzed reduction of the nascent β-ketobutyryl-ACP after the first chain extension determines the configuration of the exocyclic methyl group of BDLs. This stereocenter is R in radicicol, but S in hypothemycin, zearalenone, and dehydrocurvularin (Figure 1), highlighting a strict and chain length specific stereocontrol exercised by these enzymes.16,30 The absolute configurations of the C-15 positions of the resorcylide congeners had not been determined previously from A. zeae NRRL 45893 but were assumed to be 15(S) based on resorcylides from Penicillium sp.24,26 However, total synthesis of S-dihydroresorcylide unambiguously showed that the natural dihydroresorcylide from A. zeae is in fact the C-15 epimer (i.e., 15R).33 Similarly, in contrast to earlier reports on the absolute configuration of C-15 being S,34 most lasiodiplodin congeners from L. theobromae have later been described to feature a 15R geometry.17 Considering these ambiguities, we have used optical rotation and circular dichroism data to unequivocally establish 15R as the configuration of the exocyclic methyl groups for both trans-resorcylide (2) and desmethyl-lasiodiplodin (3) isolated from recombinant yeast. In agreement, 2 from A. zeae and 1 and 3 from L. theobromae displayed optical rotations and/or specific Cotton effects identical to those of the recombinant products. Similarly, all congeners of trans-resorcylide and desmethyl-lasiodiplodin isolated from recombinant yeast strains (see below) yielded optical rotation values and specific Cotton effects with the same sign as those of 2 and 3. Global comparison of the amino acid sequences of the KRC domains of BDL hrPKSs and comparisons with KR signature motifs in bacterial modular PKSs were uninformative, preventing primary sequence-based predictions of the stereochemical programming of the KR reactions.14,35

The ER domain of LtLasS1 is unique among the characterized BDL synthase hrPKSs as this domain is programmed to generate an alkane functionality at the last extension. All other known BDL synthases, including AzResS1, are programmed not to act at this stage, and as a result, lasiodiplodins and the recently described opioid receptor binder neocosmosins36 are the only 12- or 14-membered BDLs that lack an (E) double bond at the Southern face of their unmodified polyketide scaffolds. Global alignments of the ER domains of the known BDL synthases again failed to account for this programming difference.

LtLasS2 and AzResS2 are orthologous to characterized BDL nrPKSs11−14 and feature identical domain compositions (SAT-KS-AT-PT-ACP-TE, Figure 2B). Their SAT domains37 transfer the pentaketide (LtLasS2) or the tetraketide (AzResS2) from the ACP of their cognate hrPKS partners to initiate three (LtLasS2) or four (AzResS1) additional chain extension cycles (Figure 2B). As in the majority of nrPKS SAT domains in GenBank, the LtLasS1 SAT domain features a Cys, His active site dyad (Cys121, His246), while a Ser, His dyad is present in the active site of all other characterized BDL nrPKS (AzResS1: Ser133, His258).37 Global comparisons of the BDL hrPKSs and nrPKSs and separate alignments of their KS domains fail to cluster these enzymes according to the number of the extension cycles they are expected to conduct, nor do the sequences of the nrPKS SAT domains provide immediate clues for their substrate length preferences. Thus, the length of the linear polyketide product intermediate (octaketide for lasiodiplodin, resorcylide, and dehydrocurvularin and nonaketide for hypothemycin, radicicol, and zearalenone) and consequently the size of the BDL macrocyclic ring remain unpredictable from primary sequences alone. Evolution of substrate and product specificities in these orthologous enzymes may involve keyhole surgery of binding pocket residues by Nature.2,38

Following the assembly of the linear polyketide chain, the nrPKS PT domains catalyze a regioselective aldol condensation that yields the BDL aromatic ring.7,8,39 PT domains in RAL synthases direct an ”F-type” folding3 of the polyketide and catalyze aldol condensation in the C2–C7 register. In contrast, DALs derive from an atypical C8–C3 cyclization, resulting from “S-type” folding3 of the nascent polyketide. Irrespective of the register of the aldol cyclization, all BDL PT domains fall into the same clade in multiple sequence alignments.7,14,39 However, the regiochemical outcome of the PT-catalyzed cyclizations can be predicted (and reprogrammed) using a set of three diagnostic residues.2 The PT domains of LtLasS2 and AzResS2 contain the expected Tyr, Phe, Leu signature for C2–C7 condensations (LtLasS2: Y1443, F1563, L1571; AzResS2: Y1540, F1664, L1672), leading to the formation of their resorcylic acid moieties.

Product release from LtLasS2 and AzResS2 is catalyzed by O–C bond-forming TE domains generating RAL12 macrocycles using 15-OH as the nucleophile.10,32 The biosynthesis of isocoumarin congeners 7 and 9 on the resorcylide nrPKS (see below) involves the attack of the C-9 enol on the TE oxoester intermediate, leading to α-pyrone formation.

Minor Congeners Reveal Stuttering in RAL12 Synthases

To our surprise, careful examination of fermentation extracts of S. cerevisiae [YEpLtLasS1, YEpLtLasS2] revealed two minor RAL14 products (10 and 11, Figure 3, isolated yields 0.3 and 0.1 mg/L, respectively). A minor product with the same planar structure as 10 has been described from Monocillium nordinii as “nordinone”.40 However, the steroid 11α-hydroxy-17,17-dimethyl-18-norandrosta-4,13-dien-3-one has a precedent for this name41 so we have renamed the 17(R) isomer of the RAL14 compound as lasicicol (10). Product 11 is the 17(R) isomer of the known semisynthetic estrogen antagonist S-zearalane.41 Both lasicicol (10) and epi-zearalane (11) are nonaketides, unlike lasiodiplodin, the major octaketide product of the LtLasS system. The presence of the C-9-oxo group in lasicicol and its absence in epi-zearalane indicates a different biosynthetic origin for the extra acetate equivalent incorporated into these compounds (Figure 3). Thus, biosynthetic precedents11−16 dictate that lasicicol is derived from the same pentaketide starter as lasiodiplodin, but extended with four malonate units by the LtLasS2 nrPKS (a 5 + 4 division between hrPKS and nrPKS for lasicicol, instead of a 5 + 3 split as in lasiodiplodin). In contrast, epi-zearalane is expected to be produced with a 6 + 3 split: a hrPKS-derived hexaketide extended with three malonates by the nrPKS. We have not detected the production of 10 and 11 in L. theobromae.

Investigation of S. cerevisiae [YEpAzRESS1, YEpAzRESS2] failed to reveal the production of resorcylide congener RAL14 products. However, a minor nonaketide isocoumarin product, YXTZ-53-51-251 (9) was apparent in extended fermentations (>72 h., isolated yield 0.7 mg/L, Figure 4). Product 9 is apparently derived from the “normal” tetraketide starter of resorcylides by the addition of five malonyl units. Thus this molecule originates from a 4 + 5 division between the hrPKS and nrPKS, as opposed to the 4 + 4 split for trans-resorcylide (2). We were unable to detect the production of 9 in A. zeae.

Therefore, both the hrPKS (for epi-zearalane in the lasiodiplodin system) and the nrPKS (for lasicicol in the lasiodiplodin system and 9 in the resorcylide system) of the BDLSs may be able to produce a homologous polyketide with one extra acetate equivalent, a process referred to as “stuttering” for modular PKSs.42 Stuttering may yield minor natural congeners or could be a programmed event that yields the main metabolite.42,43 Stuttering may be provoked by unnatural intermediates during combinatorial biosynthesis44 or result from imbalances in precursor supply during in vitro synthesis with purified enzymes.32 The biosynthesis of minor RAL14 products in our heterologous host but not in the native producer fungi may reflect the differential abundance of accessible malonyl-CoA precursors in these cells, and the influence of precursor load on iPKS chain length control.

Formation of Known RAL12 Congeners

The lasiodiplodin cluster includes two genes encoding potential tailoring enzymes. LtLasM is a 398-amino-acid protein similar to S-adenosylmethione-dependent O-methyltransferases (OMT) involved in secondary metabolism (pfam00891), including the H. subiculosus hypothemycin OMT. Co-expression of LtLasM with LtLasS1 and LtLasS2 in yeast led to the almost complete conversion of 3 to lasiodiplodin (1) (Figure 3, isolated yield of 10 mg/L). Thus, co-expression of LtLasS1, LtLasS2, and LtLasM is sufficient to reconstitute the biosynthesis of lasiodiplodin in the yeast heterologous host and confirms that LtLasM is the dedicated OMT responsible for the methylation of the C-3 phenolic alcohol. Interestingly, Hpm5, the OMT from the hypothemycin cluster methylates the C-5 phenolic hydroxyl of the corresponding RAL, providing an alternative site-specific processing enzyme for future combinatorial biosynthesis. Pairing of the LtLasM OMT with the resorcylide iPKSs did not yield methylated resorcylides, indicating that the presence of the resorcylate carboxylic acid moiety is not sufficient for substrate recognition with this enzyme (Supplementary Figure S1).

LtLasG is a putative glutathione-S-transferase. The orthologous Hpm2 from the hypothemycin cluster facilitates the isomerization of the 7′,8′-trans double bond of aigialomycin through conjugation with glutathione, and this process appears coupled to the excretion of the resulting cis-isomer, hypothemycin.13 Co-expression of LtLasG in S. cerevisiae [YEpLtLasS1, YEpLtLasS2] or in S. cerevisiae [YEpLtLasS1, YEpLtLasS2, YEpLtLasM] did not yield any new RAL, nor did it facilitate the accumulation of desmethyl-lasiodiplodin or lasiodiplodin in the culture supernatants (Figure 3). Pairing of LtLasG with the resorcylide iPKSs did not alter the product fingerprint in that system either (Supplementary Figure S1). Thus, the endogenous yeast transporters are versatile enough to export resorcylide and lasiodiplodin congeners (this work), as well as other natural and hybrid BDLs.2,13−16,32

The production of the 12-, 13-, or 14-hydroxy and the 13-keto congeners of lasiodiplodin that were isolated from L. theobromae fermentations but not from our recombinant yeast strains may be ascribed to oxidative tailoring of the primary products 3-O-desmethyl-lasiodiplodin and lasiodiplodin by additional enzymes encoded at different loci in the fungal genome and/or to spontaneous oxidations in fungal fermentations.29

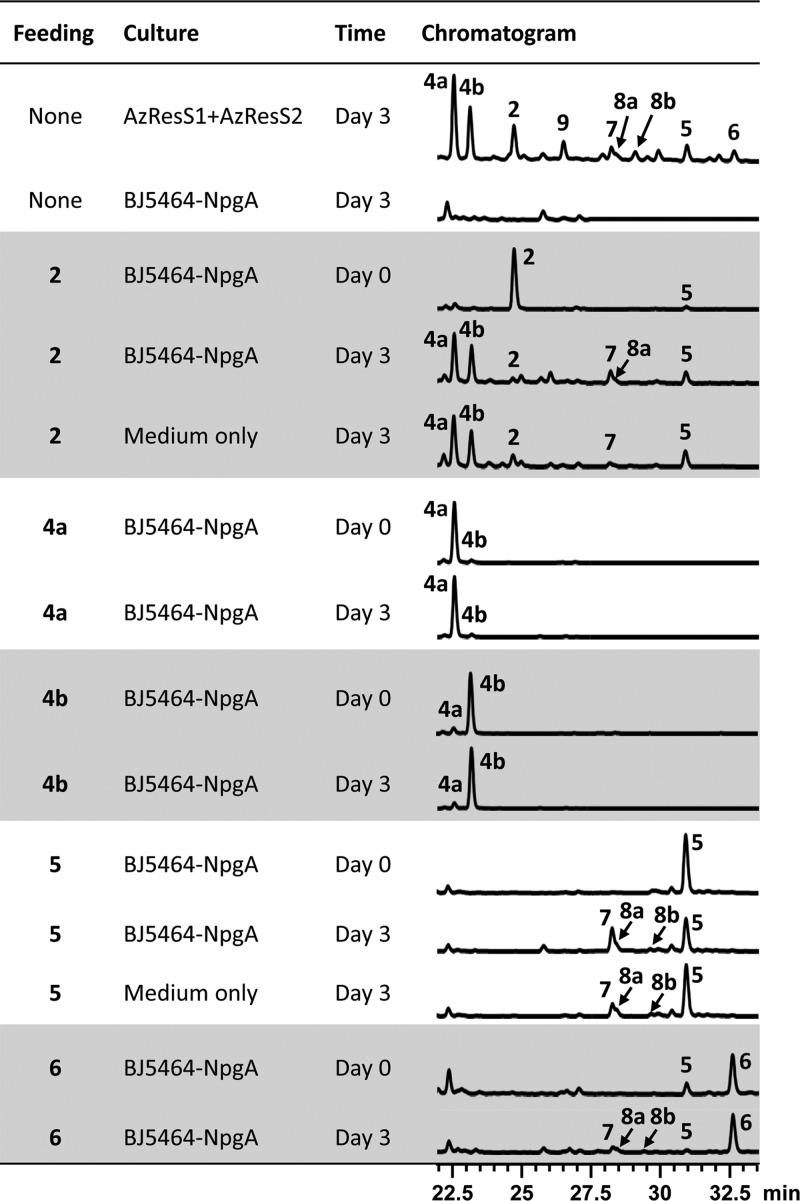

The resorcylide cluster contains no genes for the tailoring of trans-resorcylide (2), the apparent main product in the yeast host. Nevertheless, resorcylide congeners (cis-resorcylide 5, 11-hydorxyresorcylide enantiomers 4a and 4b, dihydroresorcylide 6, and 11-methoxyresorcylide enantiomers 8a and 8b) have been isolated from the producer fungi26 and were also recovered from our heterologous yeast producer strain (Figure 4). We also detected the production of small amounts of two isocoumarins, YXTZ-53-51-322 (7) and YXTZ-53-51-251 (9). A time-course analysis of the fermentation with S. cerevisiae co-expressing AzResS1 and AzResS2 (Figure 4) shows that trans-resorcylide (2) is the main product up till 48 h after the induction of polyketide production. However, 11-hydroxyresorcylides (4a and 4b) become dominant by 72 h, with congeners 5 to 9 accumulating at low yields. Extending the fermentation to 96 h and beyond did not alter the product ratios any further.

Incubation of purified 2 or 5 with the untransformed yeast host or with the uninoculated fermentation medium led to the gradual appearance of 7, 8a, and 8b (Figure 5). trans-Resorcylide 2 was readily converted to cis-resorcylide 5 regardless of the presence of the yeast host, but the reverse reaction (conversion of 5 to 2) was not observed. Hydroxyresorcylides 4a and 4b formed from trans-resorcylide (2) but not from cis-resorcylide (5) regardless of the presence of the yeast host. 11-Hydroxyresorcylides (4a and 4b) and dihydroresorcylide (6) remained stable in the presence of yeast cells or culture media. The appearance of minor amounts of 7, 8a, and 8b in incubations of 6 with or without the cells is probably due to the conversion of 5, present as a contaminant in our preparations of 6. Formation of isocoumarin 9 from purified 2, 4a, 4b, 5, or 6 was not detected in these bioconversion experiments (Figure 5). Taking these observations together, the biogenesis of the resorcylide congeners may be summarized as follows (Figure 4). The primary product of the AzResS1-AzResS2 PKS system is trans-resorcylide 2. cis-Resorcylide 5 is formed by the spontaneous isomerization of the enone in the presence of light.24 The appearance of the 11-hydroxyresorcylides (4a and 4b, respectively) in approximately 3:2 enantiomeric ratio in longer fermentations and in incubations of 2 with or without the yeast host indicates that water addition is spontaneous in the production medium. 11-Methoxyresorcylides 8a and 8b may be formed by methanol addition during workup of the extracts. Such conversions are precedented by the formation of 11-hydroxycurvularin and 11-methoxycurvularin enantiomers from 10,11-dehydrocurvularin in fermentations of Alternaria cinerariae and recombinant yeast.14 The isocoumarin 7 is produced from 2 by base-catalyzed enolization of the α-aryl ketone followed by attack of the resulting enol on the lactone, leading to the opening of the macrolactone ring and formation of the more thermodynamically stable α-pyrone ring. Dihydroresorcylide (6) is a genuine alternative biosynthetic product of AzResS1-AzResS2, originating by an off-program reduction at the tetraketide stage by the hrPKS ER domain. Finally, the isocoumarin 9 is a shunt product of the resorcylide iPKS system, resulting from a “stuttering” of the nrPKS (see earlier), followed by product release via α-pyrone formation.10

Figure 5.

(Bio)conversion of resorcylide congeners. Product profiles (HPLC traces recorded at 300 nm) of S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA31 cultures or media only, supplemented with the purified resorcylide congener at 0.025 mg mL-1 at Day 0 and incubated for the indicated amount of time.

Conclusions

Identification of the biosynthetic gene clusters for lasiodiplodin and resorcylide provides access, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, to the iPKS systems responsible for the production of the RAL12 subclass of BDLs. Exposing the apparent origins of resorcylide and lasiodiplodin congeners isolated from many fungal (and bulk plant material) sources helps to disentangle the roles that biosynthetic and chemical interconversions play in generating chemical diversity in these fungi. The close global sequence similarities of BDL synthases in the RAL14, DAL12, and RAL12 structural classes suggest that all BDL synthases are orthologous and have been the subject of repeated horizontal gene transfers and/or cluster losses during the evolution of different fungal lineages. The absence of straightforward correlations between primary amino acid sequences of key functional iPKS domains on one hand and BDL structural features (macrocyclic ring size, exocyclic methyl group conformation, or the extent of reduction at the macrolide β-carbons) on the other implicate that BDL structural variety emerges by a select few mutations in key active site cavity positions, as recently validated by us for PT domains2 and implied by combinatorial biosynthesis with alternative TE domains.10,45 Observation of RAL14 homologues during in vivo heterologous production of RAL12 metabolites extends previous observations of “stuttering” by modular PKSs43,44 to the realm of iPKSs in fungi. Together with earlier in vitro observations,32 stuttering in collaborating iPKSs indicates that precursor accessibility may override chain length control in both hrPKSs and nrPKSs. The successful heterologous production of BDLs foretells the possibility of combinatorial biosynthesis of novel BDL analogues and congeners by overexpression of heterologous iPKS pairs in various combinations, a possibility that we will address in a separate communication in due course. Such experiments will help to further exploit these interesting scaffolds against different human disease targets.

Methods

Strains and Culture Conditions

Acremonium zeae NRRL 45893 (Ascomycota, Sordariomycetes, Hypocreomycetidae, Hypocreales) and Lasiodiplodia theobromae NBRC 31059 (Ascomycota, Dothideomycetes, Botryosphaeriales, Botryosphaeriaceae) were maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Difco) at 28 °C. E. coli DH10B and plasmid pJET1.2 (Fermentas) were used for routine cloning and sequencing, while E. coli Epi300 and fosmid pCCFOS1 (Epicentre) were utilized for genomic library construction. The compatible yeast–E. coli shuttle vectors pRS425,46 YEpADH2p-FLAG-URA and YEpADH2p-FLAG-TRP14 were used to express BDL biosynthetic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA (MATα ura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 trp1 pep4::HIS3 prb1 Δ1.6R can1 GAL),31 as described.2,10,14

Cloning, Sequencing, and Sequence Analysis

Degenerate primer pairs14 were used to amplify KS- and AT-encoding regions of BDL iPKSs, using chromosomal DNA of A. zeae NRRL 45893 and L. theobromae NBRC 31059 as the templates. Specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) against amplicons encoding iPKS regions showing >50% identity to BDL iPKSs were used to screen libraries raised in pCC1FOS (Epicentre) by PCR. Fosmids AzP3B3, AzP22E9, AzP39H7, and AzP26A7 for A. zeae and separately fosmids LtP20C5, LtP40A8, and LtP69D4 for L. theobromae were mixed in equimolar ratios, and the two mixtures were sequenced using IonTorrent technology with the 314 chip (Life Technologies, Inc.). Initial assembly of the ∼200 bp reads was done with Newbler (Roche Diagnostics), followed by further iterations of assemblies with SeqMan NGen 3.1.2 (DNASTAR). Finishing was done using Sequencher 5.0 (GeneCodes Corp.), with further Sanger sequencing of the fosmids. HMM-based gene models were built with FGENESH (Softberry). The UMA algorithm was used to predict domain boundaries in PKSs.47

Production of Polyketides in Engineered Yeast Strains

Details of the construction of BDL expression plasmids are described in the Supplementary Methods. Three to five independent S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA transformants were used to survey polyketide production by each recombinant yeast strain. Fermentations with representative isolates were repeated at least three times to confirm results and scaled up to isolate products.2,14 Cultivation of yeast strains, bioconversion experiments, extraction of polyketides, and routine analysis of extracts by reversed phase HPLC were done as described.2,14 HPLC conditions for the analysis of resorcylide analogs were 5% CH3CN in H2O for 5 min, a linear 5–95% gradient of CH3CN in H2O over 10 min, and 95% CH3CN in H2O for 10 min; flow rate of 0.8 mL min–1; Kromasil C18 column (5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm); detection at 300 nm.

Chemical Characterization of Polyketide Products

Accurate mass measurements were performed with matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) on a Bruker Ultraflex III MALDI TOF-TOF instrument. Low-resolution mass measurements were done on an Agilent 6130 Single Quad LC-MS. 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR (COSY, HSQC, HMBC) spectra were obtained in CD3OD or C5D5N on a JEOL ECX-300 spectrometer. Optical rotations were recorded on a Rudolph Autopol IV polarimeter using a 10-cm microcell. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were acquired with a JASCO J-810 instrument. See the Supplementary Methods for details.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (MCB-0948751 to I.M.), the National Institutes of Health (AI065357 RM DP 008 to J.Z.), and the Elite Youth Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (to Y.X.). The authors are grateful to N. A. DaSilva (University of California, Irvine) for the strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA, Y. Tang (University of California, Los Angeles) for the YEpADH2p vectors, and Á. Somogyi (University of Arizona, Tucson) for the accurate mass measurements.

Supporting Information Available

Molecular cloning procedures, isolation and structure characterization for compounds 1—11, and additional bioinformatic analyses. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Accession Codes

The nucleotide sequence of the resorcylide and the lasiodiplodin loci appear in GenBank under accession numbers KJ434939 and KJ434938, respectively.

Author Contributions

# These authors contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Winssinger N.; Barluenga S. (2007) Chemistry and biology of resorcylic acid lactones. Chem. Commun. 2007, 22–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Zhou T.; Zhou Z.; Su S.; Roberts S. A.; Montfort W. R.; Zeng J.; Chen M.; Zhang W.; Zhan J.; Molnár I. (2013) Rational reprogramming of fungal polyketide first-ring cyclization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5398–5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R. (2001) A biosynthetic classification of fungal and streptomycete fused-ring aromatic polyketides. ChemBioChem 2, 612–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winssinger N.; Fontaine J. G.; Barluenga S. (2009) Hsp90 inhibition with resorcyclic acid lactones (RALs). Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 9, 1419–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer A.; Kennedy J.; Murli S.; Reid R.; Santi D. V. (2006) Targeted covalent inactivation of protein kinases by resorcylic acid lactone polyketides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4234–4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chooi Y. H.; Tang Y. (2012) Navigating the fungal polyketide chemical space: From genes to molecules. J. Org. Chem. 77, 9933–9953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Xu W.; Tang Y. (2010) Classification, prediction, and verification of the regioselectivity of fungal polyketide synthase product template domains. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22764–22773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. M.; Korman T. P.; Labonte J. W.; Vagstad A. L.; Hill E. A.; Kamari-Bidkorpeh O.; Tsai S. C.; Townsend C. A. (2009) Structural basis for biosynthetic programming of fungal aromatic polyketide cyclization. Nature 461, 1139–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Zhou H.; Wirz M.; Tang Y.; Boddy C. N. (2009) A thioesterase from an iterative fungal polyketide synthase shows macrocyclization and cross coupling activity and may play a role in controlling iterative cycling through product offloading. Biochemistry 48, 6288–6290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Zhou T.; Zhang S.; Xuan L. J.; Zhan J.; Molnár I. (2013) Thioesterase domains of fungal nonreducing polyketide synthases act as decision gates during combinatorial biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10783–10791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffoor I.; Trail F. (2006) Characterization of two polyketide synthase genes involved in zearalenone biosynthesis in Gibberella zeae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1793–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Xu Y.; Maine E. A.; Wijeratne E. M. K.; Espinosa-Artiles P.; Gunatilaka A. A. L.; Molnár I. (2008) Functional characterization of the biosynthesis of radicicol, an Hsp90 inhibitor resorcylic acid lactone from Chaetomium chiversii. Chem. Biol. 15, 1328–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves C. D.; Hu Z.; Reid R.; Kealey J. T. (2008) Genes for biosynthesis of the fungal polyketides hypothemycin from Hypomyces subiculosus and radicicol from Pochonia chlamydosporia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5121–5129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Espinosa-Artiles P.; Schubert V.; Xu Y. M.; Zhang W.; Lin M.; Gunatilaka A. A. L.; Süssmuth R.; Molnár I. (2013) Characterization of the biosynthetic genes for 10,11-dehydrocurvularin, a heat-shock response modulator anticancer fungal polyketide from Aspergillus terreus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 2038–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Qiao K.; Gao Z.; Meehan M. J.; Li J. W.; Zhao X.; Dorrestein P. C.; Vederas J. C.; Tang Y. (2010) Enzymatic synthesis of resorcylic acid lactones by cooperation of fungal iterative polyketide synthases involved in hypothemycin biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4530–4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Qiao K.; Gao Z.; Vederas J. C.; Tang Y. (2010) Insights into radicicol biosynthesis via heterologous synthesis of intermediates and analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41412–41421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.; Asai M.; Matsuura H.; Yoshihara T. (2000) Potato micro-tuber-inducing hydroxylasiodiplodins from Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Phytochemistry 54, 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; Takahashi K.; Matsuura H.; Yoshihara T. (2005) Novel potato micro-tuber-inducing compound, (3R,6S)-6-hydroxylasiodiplodin, from a strain of Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69, 1610–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga T. A. M.; Silva S. C.; Francisco A.-C.; Filho E. R.; Vieira P. C.; Fernandes J. B.; Silva M. F. G. F.; Mueller M. W.; Lotina-Hennsen B. (2007) Inhibition of photophosphorylation and electron transport chain in thylakoids by lasiodiplodin, a natural product from Botryosphaeria rhodina. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 4217–4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buayairaksa M.; Kanokmedhakul S.; Kanokmedhakul K.; Moosophon P.; Hahnvajanawong C.; Soytong K. (2011) Cytotoxic lasiodiplodin derivatives from the fungus Syncephalastrum racemosum. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 34, 2037–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X. S.; Ebizuka Y.; Noguchi H.; Kiuchi F.; Shibuya M.; Iitaka Y.; Seto H.; Sankawa U. (1991) Biologically active constituents of Arnebia euchroma: structure of arnebinol, an ansa-type monoterpenylbenzenoid with inhibitory activity on prostaglandin biosynthesis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 39, 2956–2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.-S.; Zhou R.; Gong J.-X.; Chen L.-L.; Kurtan T.; Shen X.; Guo Y.-W. (2011) Synthesis, modification, and evaluation of (R)-de-O-methyllasiodiplodin and analogs as nonsteroidal antagonists of mineralocorticoid receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21, 1171–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. H.; Hayashi N.; Okano M.; Hall I. H.; Wu R. Y.; McPhail A. T. (1982) Antitumor agents. Part 51. Lasiodiplodin, a potent antileukemic macrolide from Euphorbia splendens. Phytochemistry 21, 1119–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama H.; Sassa T.; Ikeda M. (1978) Structures of new plant growth inhibitors, trans- and cis-resorcylide. Agric. Biol. Chem. 42, 2407–2409. [Google Scholar]

- Nukina M.; Sassa T.; Oyama H.; Ikeda M. (1979) Structures and biological activities of fungal macrolides, pyrenolide and resorcylide. Koen Yoshishu - Tennen Yuki Kagobutsu Toronkai, 22nd 362–369. [Google Scholar]

- Poling S. M.; Wicklow D. T.; Rogers K. D.; Gloer J. B. (2008) Acremonium zeae, a protective endophyte of maize, produces dihydroresorcylide and 7-hydroxydihydroresorcylides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 3006–3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa T.; Nukina M.; Ikeda M. (1981) Electrophilic reactivities and biological activities of trans- and cis-resorcylides. Nippon Kagaku Kaishi 1981, 883–885. [Google Scholar]

- West R. R., Martinez T., Franklin H. R., Bishop P. D., and Rassing B. R. (1996) Cis-resorcylide, pharmaceutical composition containing it, and use thereof in the treatment of thrombosis and related disorders. (Zymogenetics, Inc., USA; Novo Nordisk A/S). Patent WO 9640671.

- Kashima T.; Takahashi K.; Matsuura H.; Nabeta K. (2009) Biosynthesis of resorcylic acid lactone (5S)-5-hydroxylasiodiplodin in Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73, 2522–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Gao Z.; Qiao K.; Wang J.; Vederas J. C.; Tang Y. (2012) A fungal ketoreductase domain that displays substrate-dependent stereospecificity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 331–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S. M.; Li J. W.; Choi J. W.; Zhou H.; Lee K. K.; Moorthie V. A.; Xie X.; Kealey J. T.; Da Silva N. A.; Vederas J. C.; Tang Y. (2009) Complete reconstitution of a highly reducing iterative polyketide synthase. Science 326, 589–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Zhan J.; Watanabe K.; Xie X.; Tang Y. (2008) A polyketide macrolactone synthase from the filamentous fungus Gibberella zeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6249–6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Ma W.; Xu L.; Deng F.; Guo Y. (2013) Efficient total synthesis of (S)-dihydroresorcylide, a bioactive twelve-membered macrolide. Chin. J. Chem. 31, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura H.; Nakamori K.; Omer E. A.; Hatakeyama C.; Yoshihara T.; Ichihara A. (1998) Three lasiodiplodins from Lasiodiplodia theobromae IFO 31059. Phytochemistry 49, 579–584. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Taylor C. A.; Piasecki S. K.; Keatinge-Clay A. T. (2010) Structural and functional analysis of A-type ketoreductases from the amphotericin modular polyketide synthase. Structure 18, 913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.; Radwan M. M.; Leon F.; Dale O. R.; Husni A. S.; Wu Y.; Lupien S.; Wang X.; Manly S. P.; Hill R. A.; Dugan F. M.; Cutler H. G.; Cutler S. J. (2013) Neocosmospora sp.-derived resorcylic acid lactones with in vitro binding affinity for human opioid and cannabinoid receptors. J. Nat. Prod. 76, 824–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. M.; Vagstad A. L.; Ehrlich K. C.; Townsend C. A. (2008) Starter unit specificity directs genome mining of polyketide synthase pathways in fungi. Bioorg. Chem. 36, 16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali S.; O’Hare H. M.; Weissman K. J. (2006) Broad substrate specificity of ketoreductases derived from modular polyketide synthases. ChemBioChem 7, 478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja M.; Chiang Y. M.; Chang S. L.; Praseuth M. B.; Entwistle R.; Sanchez J. F.; Lo H. C.; Yeh H. H.; Oakley B. R.; Wang C. C. (2012) Illuminating the diversity of aromatic polyketide synthases in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8212–8221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayer W. A.; Pena-Rodriguez L. (1987) Minor metabolites of Monocillium nordinii. Phytochemistry 26, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti E.; Cerutti S.; Forlani A. (1975) Action of an antiandrogen on ontogenesis in the rat. Boll. Chim. Farm. 114, 169–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss S. J.; Martin C. J.; Wilkinson B. (2004) Loss of co-linearity by modular polyketide synthases: A mechanism for the evolution of chemical diversity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 21, 575–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J.; Hertweck C. (2003) Iteration as programmed event during polyketide assembly; molecular analysis of the aureothin biosynthesis gene cluster. Chem. Biol. 10, 1225–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruheim P.; Borgos S. E. F.; Tsan P.; Sletta H.; Ellingsen T. E.; Lancelin J.-M.; Zotchev S. B. (2004) Chemical diversity of polyene macrolides produced by Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455 and recombinant strain ERD44 with genetically altered polyketide synthase NysC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 4120–4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagstad A. L.; Hill E. A.; Labonte J. W.; Townsend C. A. (2012) Characterization of a fungal thioesterase having Claisen cyclase and deacetylase activities in melanin biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 19, 1525–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson T. W.; Sikorski R. S.; Dante M.; Shero J. H.; Hieter P. (1992) Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110, 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udwary D. W.; Merski M.; Townsend C. A. (2002) A method for prediction of the locations of linker regions within large multifunctional proteins, and application to a type I polyketide synthase. J. Mol. Biol. 323, 585–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.