Abstract

The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention highlights the importance of improving the timeliness, usefulness, and quality of national suicide surveillance systems, and expanding local capacity to collect relevant data. This article describes the background, methods, process data, and implications from the first-of-its-kind community-based surveillance system for suicidal and self-injurious behavior developed by the White Mountain Apache Tribe with assistance from Johns Hopkins University. The system enables local, detailed, and real-time data collection beyond clinical settings, with in-person follow-up to facilitate connections to care. Total reporting and the proportion of individuals seeking treatment have increased over time, suggesting that this innovative surveillance system is feasible, useful, and serves as a model for other communities and the field of suicide prevention.

Suicide is a tragic event that shocks and reverberates through families and communities. In the general population, suicide deaths in children and adolescents are rare, increase in frequency in adolescence and early adulthood, and peak in late adulthood.1 However, patterns differ among American Indian (AI) populations, in which suicide peaks among youths and is less prevalent in older individuals. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for AI persons aged 15 to 24 years, and suicide rates among AI persons aged 10 to 24 years are the highest of any US racial/ethnic group.2,3 Although suicide rates vary considerably across tribes, youth suicide is one of the AI population’s most serious health disparities.4

To reduce rates of suicidal behavior, the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention5 strongly recommends to

increase the timeliness and usefulness of national surveillance systems relevant to suicide prevention and improve the ability to collect, analyze, and use this information for action through improved timeliness of reporting vital records data, increased usefulness and quality of suicide-related data, as well as the expansion of state/territorial, tribal, and local public health capacity to routinely collect, analyze, report, and use suicide-related data to implement prevention efforts and inform policy decisions.5(p79)

Existing national and regional surveillance systems6–10 are limited by (1) data collection only in clinical settings or through coroners’ reports, (2) lack of detail in data collection, and (3) delays in data reporting, which impede timely prevention and intervention development and research programs.

To address high rates of suicide in youths, the White Mountain Apache Tribe (WMAT, or Apache), with technical support from the Johns Hopkins University Center for American Indian Health (JHU), developed a community-based suicide surveillance system that has evolved to include community-based reporting of suicidal and related behavior, engagement and referral of affected individuals, and the development of prevention strategies reflecting patterns of suicidal behavior on the reservation. The system received a Bronze Psychiatric Services Achievement Award in 2011 from the American Psychiatric Association in recognition of an innovative community–academic partnership to implement suicide surveillance and prevention.11 It also received a National Behavioral Health Achievement Award for Community Mobilization in Suicide Prevention from the Indian Health Service (IHS) in 2012.

Our goal is to (1) describe the background and history of the surveillance system; (2) outline the system’s methods, including terms and definitions, surveillance system protocol and data collection forms, surveillance team roles and training, data management, and confidentiality; (3) review process data from 2007 to 2011; and (4) discuss implications for suicide prevention and public health surveillance among AIs and other at-risk populations.

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

The rural Fort Apache Indian Reservation (approximately 17 100 enrolled members) encompasses 1.7 million acres in northeastern Arizona and is governed by an elected WMAT Council. The Apaches experience substantial behavioral and mental health disparities, including high rates of school dropout, single-parent households, poverty, substandard housing conditions, adolescent pregnancy, and substance use.12–15 For more than 3 decades, tribal leaders have embraced a public health approach to these challenges, and have openly engaged in community–academic partnerships. The White Mountain Apache Suicide Surveillance and Prevention System (henceforth abbreviated as the Apache Surveillance System or the system) is a prime example.

The Apache Surveillance System was established by tribal resolution in 2001, after a spike of 11 suicide deaths, a number of which were in youths younger than 20 years of age. All reservation-based first responders (e.g., emergency, fire and police departments, and emergency medical service personnel) were mandated to report any observed or documented suicide ideation, attempts, and deaths by any person on the reservation to a central Suicide Prevention Task Force, now referred to as the Celebrating Life team. An annotated timeline for how the system evolved is illustrated in the box on page e2. In summary, its development has advanced in 2 major ways: (1) refinement of data collection and (2) the scope of the tribal mandate. Data collection updates include translating paper and pencil forms to Internet-based data management for real-time tracking and reporting, updating variables to reflect community understanding of risk factors and current nomenclature for suicidal behavior,17 and corroborating data with community sources (police, IHS, and local providers and emergency responders) and through in-person validation with reported individuals. Tribal mandate updates include reporting by all persons, departments, and schools within the WMAT jurisdiction, in-person follow-up and facilitated treatment referral by the Celebrating Life team, and addition of nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) and binge substance use to the list of reportable behaviors. All surveillance system protocol changes are vetted through the WMAT Council and Health Board and require formal approval.

BOX 1—Timeline of an American Indian Tribally Initiated Suicide Prevention System, 1993–2011

| Recognizing suicide as a preventable public health problem |

| • In December 1993, in the midst of a youth suicide epidemic on the Apache reservation, tribal leaders petitioned John Hopkins University (JHU; Baltimore, MD), which had a 15-year history in the community jointly working with the Tribe to eradicate childhood mortality because of infectious diseases, for help to reduce the tragic deaths of many tribal youths. |

| • In January 1994, a meeting was held at JHU, which kicked off several years of work on the issue. |

| • JHU public and mental health experts assisted by conducting a quantitative and qualitative analysis of suicides for a 4-year period (1990–1993), which were identified as the “epidemic” years by the Tribal Health Authority (now called the Division of Health) and the Apache Police Department.16 |

| • Between 1994 and 2001, White Mountain Apache Tribe (WMAT) experienced a decrease in suicide deaths. However in the first 6 months of 2001, the WMAT had another spike in suicide, with the deaths of 11 individuals, many of whom were youths. |

| Determining ongoing surveillance was the best first step of a public health approach |

| • In January 2001, the Tribal Council established a Suicide Prevention Task Force in response to this public health crisis, now referred to as the Celebrating Life team. It provided its leadership the authority to begin to educate the community and to collect and track data on suicide attempts and deaths—creating a suicide registry or surveillance system. |

| • Reports were made using a uniform paper intake form adapted from a suicide report form used by the Indian Health Service. |

| Garnering support among key stakeholders to pass community-based surveillance |

| • In February 2006, the tribal resolution that required (mandated) all community members to report the suicide ideation, attempt, or death of another community member to the Celebrating Life team was passed. |

| Maintaining and adapting the system over time |

| • In 2002, tribal members identified youth suicide as a priority issue for the Native American Research Centers for Health (NARCH) partnership to address during the NARCH III grant submission period (submitted June 2003, funded September 2004). Two of the goals of the grant were to computerize the surveillance system and expand the variables collected. |

| • In 2006, tribal stakeholders added the in-person follow-up and referral process. In addition, they expanded the surveillance system to include NSSI because many incidents originally reported as “attempts” were subsequently identified as nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) by the Celebrating Life team after direct follow-up with individuals. |

| • In 2010, binge substance use was added as discreet reportable behaviors with or without co-occurrence of other forms of self-injury because the follow-up process also identified that substance abuse was frequently co-occurring with intentional self-injury. |

METHODS

Definitions for reportable behaviors are modeled on the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment (C-CASA).17 Suicide is a death resulting from intentional self-inflicted injury as determined by the local medical examiner or authorized law enforcement official. Suicide attempt is intentional self-injury with intent to die. (Aborted and interrupted suicide attempts are included as part of this category). Suicidal ideation is thoughts to take one’s own life with or without preparatory action. NSSI is intentional self-injury without intent to die. Binge substance use (not part of the C-CASA system) is locally defined as consuming substances with the intention of modifying consciousness and resulting in severe consequence, including being found unresponsive or requiring emergency department (ED) treatment.

System Protocol and Data Collection Forms

Overview.

The surveillance system functions as follows: (1) When an initial report (intake) is made to the surveillance system, a Celebrating Life team member seeks out the reported individual to complete an in-person interview (follow-up). Follow-ups take place at the person’s home or another private setting. In the case of a suicide death, police records are the primary source of information. (2) The Celebrating Life team, with support from the JHU Technical Assistance team, reviews the information and reaches consensus on final coding (confirmation). (3) The Celebrating Life team refers the individual to appropriate services (referral).

The data collection forms were copyrighted by the Apache in 2010; the most recently approved versions are included as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org.

Intake.

The intake report is typically made by the individual who observed or became knowledgeable of a person with self-injurious behavior (i.e., medical, school and social service personnel, first responders, religious leaders, family members, and peers). The majority of reports are made in real time; however, some are made well after the event. The intake form is submitted to the Celebrating Life team via hard copy, fax, or over the phone. Data gathered on the intake form include the reporter’s information (e.g., name, contact information, date of report, relationship to individual), the affected individual’s demographic characteristics (e.g., name, contact information, age, gender, educational status, and marital status), behavior details (e.g., date, suicidal, or self-injurious behavior type, geographic location of the event, method, concurrent substance use, and previous suicidal behavior), and follow-up information (e.g., if taken to ED, arrest, hospitalization). Reports are accepted even if incomplete; the Celebrating Life team gathers missing data during the follow-up visit.

Follow-up.

The follow-up visit with the reported individual gathers details about the event and other relevant information, including confirmed behavior intent and type; further details about the event (e.g., function of and precipitants for behavior, impact of friends’ and family members’ suicides and attempts); mental health and substance use history; service utilization; and other risk and potential protective factors (e.g., involvement in traditional and religious activities).

Celebrating Life team members attempt to complete the follow-up within 24 hours of intake report receipt. If the individual is not located, the Celebrating Life team will make repeated attempts for up to 90 days for youths younger than 20 years (longer limit because of higher risk) and 30 days for adults (maximum of 4 attempts to find). For minors not reported through the school system, efforts are made by the Celebrating Life team to talk with the parent(s) or legal guardian(s) before or at the same time as youths to inform them of the report and gather additional information about the event. When parents or guardians are unavailable, the mandate dictates the Celebrating Life team still interview youths, if willing. For minors reported through the schools, the school contacts the parents about the follow-up, and permission is sought before the visit can occur.

Suicide.

The death by suicide form is completed by the Celebrating Life team from information in the police report. The Celebrating Life team does not currently interview family members or friends of the deceased out of respect for the family during this time of mourning, as taught by their cultural practices. Data gathered on the suicide form include demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, living, status, and children), suicide details (e.g., date, method, location and time of death, concurrent substance use, and suspected precipitant[s]), and service utilization (e.g., history of residential care, treatment before death).

Confirmation.

The system’s confirmation protocol is designed to minimize misclassification. Behaviors are confirmed with information obtained from in-person follow-up, and can be supplemented by information from police reports, IHS medical records, local providers, and first responders. The Celebrating Life team reviews all gathered information and reaches consensus on final event classification. Classification of the event is based on stated intent, congruence of method with intent, lethality of method, reported function of the behavior, and concurrent substance use. When no other source contradicts the individual’s report, the classification is based on the individual’s report. When there are contradictions among data gathered, a review of all data is conducted, and a consensus procedure is initiated to determine the event classification.

Referral.

The Celebrating Life team refers all reported individuals to Apache Behavioral Health Services (ABHS), the local community mental health center mandated by the Apache to evaluate reported individuals for appropriate services. Referrals occur immediately when a report is received by the system. When the Celebrating Life team conducts the in-person follow-up, they check whether the youths or family have connected with ABHS, and make an additional referral if necessary. For minors, parents or guardians are notified, if available, of the referral by the Celebrating Life team to facilitate treatment. If minors seek treatment elsewhere or express disinterest, the Celebrating Life team is still required by the mandate to complete the ABHS referral, but will also facilitate connection to other local care providers (e.g., traditional healer, church, IHS social services and mental health, and private providers).

Team Roles and Training

Celebrating Life team.

Since the surveillance system’s inception, 12 staff members, 5 of whom are current, have been trained as part of the Celebrating Life team. They are tasked with

educating community members and departments about the system and reporting procedures through regular in-services,

supplying and collecting intake forms,

contacting all reported individuals for follow-up and facilitating contact with ABHS and other preferred providers,

online data entry,

distributing quarterly and annual surveillance data to the WMAT Council and local IHS hospital, and

liaising with community stakeholders to interpret data and develop prevention programming.

Celebrating Life team members are Apaches, have a high school diploma, some college or a college degree, previous public health work experience, strong interpersonal skills, and knowledge of Apache and English languages. Currently, Celebrating Life team members are hired on a full-time basis, trained by JHU, and supported through grant funding.

The Celebrating Life team is uniquely suited to manage the Apache Surveillance System. As members of the community, they are knowledgeable and empathetic regarding potential risks and precipitants of suicidal and self-injurious behavior. They are facile in establishing a comfortable and trusting relationship during the follow-up visit with reported individuals and family members to ease data collection, provide support, and facilitate referrals. They effectively problem-solve barriers to compliance with referrals and enhance continuity of care. Follow-up visits often occur in the individual’s home and sometimes involve other family members. Celebrating Life team members are trained and skilled in creating a positive atmosphere during follow-up visits and engaging family members in referral and treatment plans.

Johns Hopkins University Technical Assistance Team.

At any time, up to 5 JHU mental and public health personnel, with training in psychiatry, psychology, social work, and public health, provide the following technical assistance:

training in suicidal and self-injurious behavior classification and coding difficult cases;

re-drafting forms to reflect new behaviors or variables of community concern;

managing and analyzing data;

disseminating methods and findings locally and nationally;

training in engagement, interview, and crisis management strategies;

stress management training and self-care;

working with community stakeholders to advance suicide prevention service and research programs based on findings; and

consulting with other tribes who are seeking to adopt a similar public health approach to suicide prevention.

Celebrating Life Team training and quality assurance procedures.

In addition to the previously mentioned training experience, Celebrating Life team members are trained in person by the local Celebrating Life team director and the Johns Hopkins Technical Assistance team in surveillance system protocols, working with an at-risk population, maintaining privacy and confidentiality, and human ethics standards. Supervision is conducted via weekly team meetings with the local Celebrating Life director, and via bimonthly conference calls and quarterly site visits with the Technical Assistance team. The protocol for completing surveillance forms is documented and updated as needed in a policies and procedures manual. Quality assurance is performed quarterly by the local Celebrating Life director by observing follow-up visits conducted by Celebrating Life team members.

Data Management

Intake, follow-up, and death by suicide forms are entered into a secure, online database and stored in a locked file cabinet in the local program office. The database is password protected and only accessible to team members. A double data entry system is used for validation and quality assurance. Senior members of the Celebrating Life and Technical Assistance teams perform monthly reviews to check for and address missing data. Trends pertaining to behaviors and sociodemographic characteristics are analyzed on a quarterly, semiannual, and annual basis, and reported to the WMAT Council and the clinical director and preventive medicine epidemiologist of the local IHS hospital. Year-to-year trends are monitored to advise tribal leadership and key stakeholders on pattern changes that may aid in early identification and intervention with those at risk. Data are interpreted iteratively between the Celebrating Life team, the JHU Technical Assistance team, and tribal leaders. Related presentations and articles are reviewed and approved by the WMAT Council and Health Advisory Board.

Confidentiality

As a sovereign nation, the White Mountain Apache Tribe has established that individuals with self-injurious behavior are reported to the surveillance system by tribal law, and not via individual consent. From a Western perspective, some may view the tribal mandate as disregarding an individual’s human rights. However, from an Apache tribal perspective, and perhaps other AI tribal perspectives, the tribal reporting mandate reflects the tribe’s collective will to address suicide and self-injurious behaviors as a serious and life-threatening public health problem that demands immediate, caring, and culturally appropriate follow-up and referral. The tribal leadership that created and has maintained this system values the importance of an individual’s health needs (and ultimately community health needs) over an individual’s right to privacy. Communal support and endorsement for the system is reflected by the fact that reports are made by individuals from a variety of backgrounds, not just professionals and agencies. The use of mandating reporting of self-injurious behavior as a public health approach to prevention is consistent with other reportable mandates. The expansion of the Apache’s public health approach to self-injurious behavior reflects the tribe’s dedication to give similar attention to mental health issues, as well as infectious diseases, child abuse, and neglect.

RESULTS

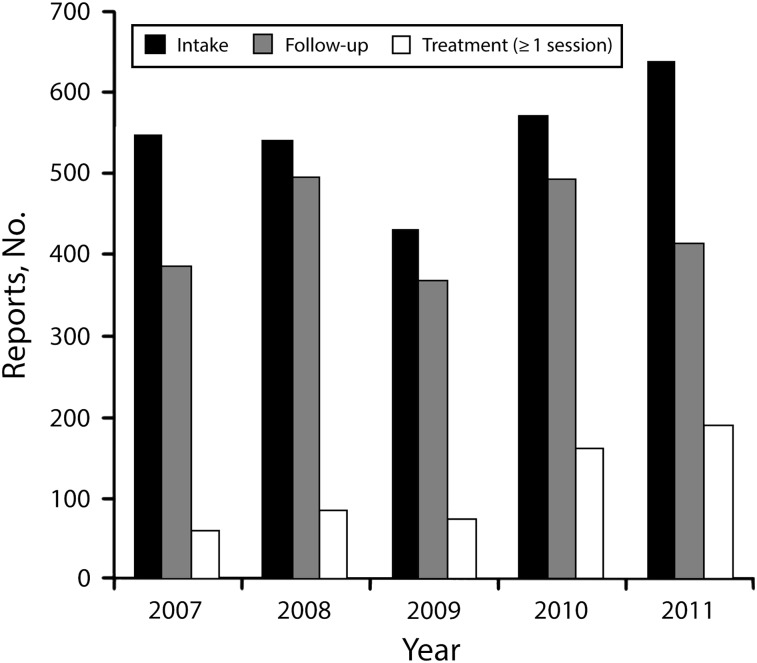

Process data from the surveillance system can help address important considerations for the field of suicide prevention and communities considering their own surveillance system (Figure 1). From 2007 to 2011, the total volume of intake forms received by the Apache Surveillance System for a community of approximately 17 100 members was 2640, including 976 for suicide ideation, 758 for NSSI, and 906 for suicide attempt. In the 5 most recent years, reports increased from 519 in 2007 to 627 in 2011, which, after taking population growth into account, suggests an overall increase in reporting rates. This increase appears to be related to greater awareness of the system and increasing willingness to report events, and not necessarily a worsening problem, because increases in reporting have been concentrated in lower severity behavior categories (e.g., suicide ideation and NSSI), which is indicative of perhaps increased community sensitivity to behaviors earlier in the progression of risk. Successful follow-ups (i.e., staff were able to find and interview the individual) have also increased from 19% in 2006 to an average of 80% of all intake reports during this time frame (2007–2011). This marked improvement is likely the result of the increased staffing ratio, the staff’s greater comfort and expertise in locating individuals in the community, and increased communal knowledge and acceptance of the surveillance system. Related to continuity of care and help-seeking, the proportion of individuals referred who subsequently reported seeking treatment has nearly doubled in 5 years from 39% in 2007 to 71% in 2011. We hypothesize that this increase may be attributed to more systematized training and protocols for local staff with regard to follow-up interviews and referral, increased communication and networking within the local mental health system supporting better continuity of care, and ongoing development of a comprehensive community-based suicide prevention program (i.e., universal, selective, and indicated levels) rolled out during this time frame, with support from consecutive Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration grants (5SM057835; 9SM059250).

FIGURE 1—

Apache Surveillance System process data: 2007–2011.

Rates of suicide death and attempts were last analyzed using surveillance data from 2001 to 2006 and published by the Journal in 2009.18 Because of the size of the population and the rarity of the behavior from a statistical standpoint, rates were analyzed for 5-year time periods. Data from 2007 to 2012 are currently under analysis, and because of the increased quality of follow-up and verification procedures, analyses will allow inferences about how the surveillance system may be affecting trends in behaviors across the suicide spectrum, including rates of death, attempts, and ideation, as well as nonsuicidal self-injury.

DISCUSSION

The WMAT has demonstrated the feasibility and utility of an innovative, mandated community-based surveillance system for suicidal and self-injurious behavior—the first of its kind in the United States and internationally. Overall, reporting has increased over time, suggesting greater awareness and implementation by the community at large. The local Celebrating Life team is successfully conducting in-person follow-up on reports and facilitated connections to care for the majority of individuals who evidence self-injurious behavior.

The strengths of the tribally mandated Apache Surveillance System offer several opportunities for addressing the public health problem of suicide. First, the Apache system is uniquely able to gather accurate, real-time data to track trends and capture characteristics of suicidal behavior beyond clinical settings and coroner-level data to advance prevention strategies. Second, the comprehensive system (including suicide ideation, attempts, and deaths, and NSSI and binge drinking) allows for examination of the relationships among behaviors along the continuum of self-injury, providing a deeper understanding of patterns of suicide behavior across time, including potential contagion effects, in a population-based sample. Third, the system demonstrates how community mental health workers can play a key role in continuity of care for suicidal individuals, which is particularly important in rural and under-resourced communities with low access to mental health care. Fourth, the system provides an innovative model of collective consent to identify and assist persons engaging in suicidal and self-injurious behaviors—a population who often does not seek help and has trouble connecting with treatment—as part of a comprehensive public health response.

In parallel with these health system innovations, the Apache Surveillance System has resulted in high quality tribal specific data that are being utilized for a parallel program of community-based suicide prevention research (IHS/NIH: 1S06GM074004; U26IHS300286; U26IHS300414). For example, the system identified that suicidal youths were often first seen for their attempts in the ED, and medical chart review data indicated that 82% of youth attempters had an ED visit for any reason and 26% for a psychiatric reason in the year before their attempt, including suicidal thoughts or self-harm.18,19 Based on this knowledge, the community–academic partners developed and pilot tested an ED-linked intervention for this subgroup that has shown reductions in self-reported depression, negative cognitive thinking, and suicidal ideation, and increases in treatment-seeking (M. F. C, unpublished data). The important role of substance use in the spectrum of self-injury has also emerged from surveillance data,12,20 and led to further research to address its function and comorbidity among suicidal Apache youths.13

There are also notable limitations to the tribally mandated surveillance system. First, intake data are sometimes missing or erroneous because of third party reports directly from community members. However, the follow-up protocol allows for additional data to be collected or corrected if necessary. Second, upon follow-up, completing data collection and classifying the behavior can be challenging, especially when severe substance use is involved and reported individuals cannot remember events. Third, the uniqueness of the tribally mandated community-based surveillance system limits direct comparison with other surveillance system data. Fourth, because the system has been grant funded to date, there are periods when it is better resourced and staffed, but it is always under threat of not being sustainable. In response, the tribal–academic partners are currently working on a sustainability plan. Finally, mandated reporting may increase stigma for suicidal individuals; however, one may argue the tribe’s overt approach to treating suicide as a reportable disease to hasten individual treatment may ultimately de-stigmatize mental illness. Along the same vein, Western perception of the possible risks of disregarding individual privacy must be weighed against the larger threat of death by suicide and its reverberating impact on families, community, and Apache cultural and population survival. The most important evidence to date countering concerns about stigma and privacy are (1) reports to the system have increased over time and (2) Celebrating Life team members and other community stakeholders indicate that few individuals refuse follow-up. Finally, the fact that the tribe has nominated a trusted outside public health institution to monitor the system and train local staff to mastery in handling individual data and human confidentiality provides additional safeguards to protect confidentiality in a relatively small, tight-knit community.

Several components were critical to feasibility among the Apache and would need to be addressed by other communities seeking to replicate this system. First, the Apache leadership and key community members identified suicide as a preventable public health problem and were ready to address it. Second, the WMAT, as a sovereign nation, was able to mandate surveillance as the first step in a public health approach, and the cultural norms of the tribe support its members in embracing the concept of collective consent over individual concerns about privacy and confidentiality. Third, the size and close-knit structure of the Apache reservation community allow for potential reach of the entire population. With the current Apache population, the size of the reservation, and level of suicidal behavior, it is estimated that 5 to 7 full-time employed community mental health workers are needed at any one time, funded between 50% and 100%. Finally, a strong, long-term community–academic collaboration has facilitated the evolution of the system to address tribal needs and benefit from local expertise, research, and clinical knowledge. Academic partners currently provide approximately 20% total for consultation and supervision, with more time during startup. Additionally, a data analyst provides approximately 15% effort; however, some tribes may have this capacity locally.

The Apache Surveillance System applies a novel public health approach to collect local data, inform suicide prevention strategies, and enhance continuity of care, which can be a model for other rural and disadvantaged communities. Local, trained Native community mental health workers comprising the Celebrating Life team are combining a rigorous approach with a compassionate mission to successfully address barriers to identification and service utilization. The system holds promise to prevent suicide both directly and indirectly and reduce medical costs and burden through use of local paraprofessionals to advance early identification, facilitate connections to care, increase community awareness, and inform targeted prevention and treatment interventions.

Acknowledgments

We respectfully acknowledge the White Mountain Apache Tribal Council and Health Board for their courage in addressing suicide and innovation in mandating community-based surveillance. We are grateful to the Native American Research Centers in Health (NARCH) initiative, which provided grant support for this project from the National Institute of General Medical Science and Indian Health Service (grant U26IHS300013; Study PI, J. W.; NARCH PI, M. C.).

We also acknowledge Elena Varipatis Baker and Britta Mullany for their past technical support to the system, Elizabeth Ballard for her assistance with the literature review, and most importantly the Apache Celebrating Life team for their tireless dedication to help their community.

Note. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Indian Health Service.

Human Participant Protection

The surveillance system is tribally mandated, which is the equivalent of institutional review board approval. Analyses in this article are covered under this approval.

References

- 1.Pelkonen M, Marttunen M. Child and adolescent suicide: epidemiology, risk factors, and approaches to prevention. Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5(4):243–265. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200305040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gary FA, Baker M, Grandbois DM. Perspectives on suicide prevention among American Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents: a call for help. Online J Issues Nurs. 2005;10(2):6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlow A, Walkup JT. Developing mental health services for Native American children. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1998;7(3):555–577. ix. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemp J, Bossarte RM. Surveillance of suicide and suicide attempts among veterans: addressing a national imperative. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):e4–e5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christiansen E, Jensen BF. Register for suicide attempts. Dan Med Bull. 2004;51(4):415–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang HC, Chen HS, Tai CW, Lee MB. National suicide surveillance system: experience in Taiwan. 2006 8th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (HEALTHCOM 2006) 2006:160–164. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulozzi LJ, Mercy J, Frazier L, Jr, Annest JL. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s national violent death reporting system: background and methodology. Inj Prev. 2004;10(1):47–52. doi: 10.1136/ip.2003.003434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry IJ, Corcoran P, Fitzgerald AP, Keeley HS, Reulbach U, Arensman E. The incidence and repetition of hospital-treated deliberate self harm: findings from the world’s first national registry. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver and bronze achievement awards. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(11):1390–1392. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlow A, Tingey L, Cwik M et al. Understanding the relationship between substance use and self-injury in American Indian youth. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):403–408. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.696757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tingey L, Cwik M, Goklish N et al. Exploring binge drinking and drug use among American Indians: data from adolescent focus groups. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):409–415. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.705204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.First Things First White Mountain Apache Tribe Regional Partnership Council. 2012 needs and assets report. Phoenix, AZ: Arizona Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginsburg GS, Baker EV, Mullany BC et al. Depressive symptoms among reservation-based pregnant American Indian adolescents. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(suppl 1):110–118. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wissow LS, Walkup J, Barlow A, Reid R, Kane S. Cluster and regional influences on suicide in a southwestern American Indian tribe. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(9):1115–1124. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia classification algorithm of suicide assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1035–1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullany B, Barlow A, Goklish N et al. Toward understanding suicide among youths: results from the White Mountain Apache tribally mandated suicide surveillance system, 2001-2006. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1840–1848. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballard ED, Tingey L, Lee A, Suttle R, Barlow A, Cwik M. Emergency department utilization among American Indian adolescents who made a suicide attempt: a screening opportunity. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(3):357–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cwik MF, Barlow A, Tingey L, Larzelere-Hinton F, Goklish N, Walkup JT. Nonsuicidal self-injury in an American Indian reservation community: results from the White Mountain Apache surveillance system, 2007–2008. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(9):860–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]