Abstract

The objective of the study is to provide information about non disease specified outcome measures which evaluate disability in patients who have impairments in hand and upper extremity and to find the extent to which they are evaluating “disability” based on ICF hand Core Set (activity limitation and participation restriction). MEDLINE, CINAHL, GOOGLE SCHOLAR , OVID and SCIENCE DIRECT databases were systematically searched for studies on non disease specified outcome measures used to evaluate upper extremity function; only studies written in English were considered. We reviewed titles and abstracts of the identified studies to determine whether the studies met predefined eligibility criteria (eg, non disease specified out come measures used in hand injured patients). All the outcome measures which had eligibility included. After full text review ,7 non disease specified outcome measures in hand were identified. Studies were extracted, and the information retrieved from them. All the outcome measures which had incuded, were linked with ICF hand core set disability part (activity and participation). All of them only linked to 16 (42 %) components of ICF hand Core Set, which were most activity and less participation from ICF. None of the non disease specified out come measures in hand injuries cover all domains of disability from the ICF Hand Core Set.

Keywords: Hand, Outcome measure, Review, ICF, Disability

Introduction

The upper extremity is integral to activities of daily living, self-care, work, leisure, and social activities. Any injury that affects this part of the body can impair its structure and function. Impairment in hand can cause problems such as limitation in “range of movement” and/or “sensation and power”, which can lead to disability. Although disablity is one of the hot topics in literatures, there is no complete agreement on its definition, which, in turn led to difficulty in developing and measuring outcome measures.

Disability is the functional consequence of impairment and is defined as an alteration of an individual’s capacity to meet personal, social or occupational demands. The relationship between disability and impairment is not a linear one. An impaired individual may or may not have a disability. But in contrast, based on defnition of the ‘Americans with Disabilities’ Act [1], an individual with a disability does have a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. Also, some authors [2] argued that disability is an incapablity of doing an action .

The attempt to define the disability began in 1950. In these initial attempts, impairment of any given severity were considered as sufficient to result in disability in all circumstances, in spite of practicing rehabilitation before then. However, the conceptual frameworks for modeling disability, which considered effects of rehabilitation on disability, were not appeared until 1970s [3]. These conceptual frameworks allowed greater scientific inquiry into both disability and rehabilitation. In 1972, World Health organization (WHO) provided a medical model of illness to evaluate health care that resulted in the foundation of International Classification of Disease (ICD). However, in 1980, it changed its focus toward the consequences of diseases and developed the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps [4].

As environmental factors can play a critical role in disabilty [5], Nagi proposed a disability model that recognized the role of environment in explaning disability [6].

Later on, the International Classification of Function (ICF) were developed as revision of the ICIDH. The idea was to use less pejorative language (e.g., “participation” replaces “handicap” as a functional domain), incorporating environmental and personal factors as “contextual factors” that affect disability outcomes, and recognizing multiple levels and directions of potential causal relationship, [7, 8]. The ICF puts the notions of ‘health’ and ‘disability’ in a new light. It acknowledges that ” every human being can experience a decrement in health and thereby experience some degree of disability” [9].

Although disability is not something that only happens to a minority of humanity, ICF takes into account the social aspects of disability and does not see disability merely as a ‘medical’ or ‘biological’ dysfunction [10].

According to ICF category, there are two parts in defining health. Part 1 covers functioning and disability including body function and structure, activities, and participation. Part 2 deals with contextual factors and includes environmental and personal factors. The model conceives these components as separate but related constructs with dynamic interactions between health conditions [9]. Based on ICF, impairment is defined as a problem in the body function or structure that results in a significant deviation or loss. Activities refer to the execution of a task or action by an individual, and participation refers to involvement in a life situation [10]. Body functions and structures impairment are not necessarily coupled with activity limitations or participation restrictions. Sometimes, minor impairments can lead to substantial activity limitations or participation restrictions.

To ICF, disability is an umbrella term for activity limitations and participation restrictions [11]. Not all impairments result in disabilities, therefore a person can be disabled but not handicapped [12].

To make the ICF applicable in practice and to allow a user-friendly description of functioning and disability, ICF Core Sets have been developed. It facilitates the description of functioning in clinical practice by providing lists of categories that are relevant for specific health conditions and health care contexts [13]. The comprehensive ICF Core Set for Hand Conditions has been adopted and validated in a national multicenter study and its main purpose was to guide multidisciplinary assessments in treatment and rehabilitation of the hand-injured patients. Core Set contains a set of 117 ICF categories [14].

In the therapeutic process, hand therapists determine which impairments are contributing to disability and design a treatment plan. They need to evaluate changes in impairment and disability over time to know whether treatments are efficacious. They also need to demonstrate to others that their treatment resulted in a clinically important improvement [15].

Impairment evaluation is done routinely in hand clinics (like evaluation of range of motion with goniometer or sensation with monofilament) [16]. However, disability is influenced not only by impairment but by patient related subjective factors [17]. Therefore, an outcome assessment tool should measure both of these separately. Such outcome tools can measure the effectiveness of treatment regimens and rehabilitation protocols more precisely.

With this development in understanding, an outcome measure that contains the meaning of disability in ICF hand Core Set is now needed. There are self-repoted questionnaires that purported to evaluate disability in hand injuries. Some of these questionnaires target general hand conditions (Non disease specified) and some target specific conditions like rheumatoid arthritis questionnaire. To know how much the concepts of ICF is being considered in them, linking to ICF codes were done [18–23]. Since according to ICF, disability is an activity limitation and participation restriction, in order to evaluate disability in hand, the questionaries must be linked with activity and participation part of ICF hand core sets.

In the recent years, various subjective hand function (disease specified or non disease specified) questionnaires have been developed to improve the quality of evaluation [24, 25].

The aim of this review is to find the extent to which available non disease specified outcome measures in hand injured patients are evaluating “disability based on ICF hand Core Set” (activity limitation and participation restriction).

Methods

Study Design

This review was done in two steps. In the first step, literature was reviewed to identify the non disease specified outcome measures in hand injuries. As the self-report outcome measures can provide subjective information of patients to assist in decision making in therapeutic process [26], we only included self-report outcome measures. In the second step, the selected measures were examined to find the extent to which their items are linked with ICF hand Core Set and meanings of disability (activity and participation as coded “d”).

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

First, the MEDLINE, CINAHL, OVID and SCIENCE DIRECT databases were searched. The following keywords or Mesh-terms were combined with “OR” then by “AND”; “upper extremity”, “hand”, “arm”, “assessment”, “measure”, “measurement”, “instrument”, “test”, “evaluation”, “outcome”, “scale”.

Then, the names of previously identified measures were entered in a database by combination with: “function”, “activity”, “activities”, “performance” and “ICF”. Studies with Non-human population, languages other than English or with no full text available and studies, which used disease specified outcome measures were excluded. Applying the same general and specific eligibility criteria, the abstracts also were checked. Then, the full texts were reviewed and the same criteria were used. Finally from 2380 articles, 2130 articles were excluded after going through their title and abstract. Full texts of 79 articles were reviewed. After this full text review, 7 non-diseases specified outcome measures in hand were identified.

Data Extraction and Results

Measures and Their Purpose

After reviewing the studies, seven non diseases specified outcome measures in hand disorders were selected. They were analyzed to find out their authors’ purpose of developing them. They were evaluated further to find out the extent to which they matched with ICF definition of disability (part of activity and participation in hand core Set) (Table 1).

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH), [27] was developed to assess body function, participation and two types of activities (single tasks and total)[28]. It has 30 items that address arm-specific symptoms and disability during the preceding week. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale. The overall score is scaled from 0 (no disability) to 100 (most sever disability). The majority of the questions are concerned with functional activities requiring use of the upper extremities, and the remaining questions include the followings: 2 items specifically relating to pain, 3 questions relating to other symptoms, one question addresses social life, one is directly related to work, one is related to sleeping, and one item aims to determine the patients perceptions of their own capabilities. It contains two modular parts: work and leisure with 8 items.

Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ) [29] is a questionnaire composed of 37 items to evaluate body function, activity and participation [28, 30]. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The overall score is ranged from 0 (most sever disability) to 100 (no disability). It is specifically related to the hand and is categorized under the following six domains: 1) overall hand function, 2) activity of daily living, 3) pain, 4) work performance, 5) aesthetics, and 6) patient satisfaction of hand functioning.

Table 1.

Description of the data of the questionaires

| Measure | Target population | Number of scales | Number of items | Range of scores | Studied populations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASH [27] | Upper-extremity Musculoskeletal conditions | 1 | 30 + 8 | 0-100 | Shoulder and hand/wrist Disorders, acute hand/wrist Trauma, diverse hand/wrist Surgery |

| MHQ [29] | All types of hand/wrist conditions | 6 (ADL, pain, work, function, Aesthetics, Satisfaction) | 37 | 0-100 | Hand/wrist disorders referred for Surgery |

| HAT [39] | All types of hand/wrist conditions | 7 (ADL, Fine hand skill, pain, Extension, Neurotic, Symptom, gross grasp Aesthetic) | 30 | 0-100 | Hand/wrist disorders |

| MAM-16 [36, 39] | All type of hand impairment | 1 | 16 | 0 -100 | Variety hand impairment |

| POS-hand/arm [37] | Hand and arm disorders | 2 | 13 | 0 - 100 | Pre and post surgery |

| PEM [39] | Hand impairment | 3 (symptom, Function, satisfaction) | 19 | Percent of total | Hand/wrist disorders Function and outcome |

| ABILHAND [38] | Manual hand ability | ADL | 23 | RA |

Each of the categories of MHQ is subdivided into right and left hand specific items, with the exception of the pain and the work performance categories. It contains a set of questions on bilateral task performance.

-

3)

Hand Assessment Tool (HAT) [31], is a questionnaire composed of 14 items specifically related to the task performance of hand and wrist during past week. It was developed to address a full range of activities for patients with injuries specific to the hand and wrist [32–34]. It is categorized under 7 domains; 1) firm grip, 2) fine hand skills, 3) pain, 4) extension, 5) neurotic symptoms, 6) gross grasp, and 7) aesthetic. The HAT does not calculate a separate right and left hand score; however, hand dominance and location of injury are noted on evaluation. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The total score is ranged between 0–100 and calculated by formula with higher score representing greater activity limitation.

-

4)

Manual ability measure (MAM) [35], was developed as a task oriented and patient centered tool that measures manual ability. It is a Rasch-built questionnaire with 16 items representing common tasks to tap into full range of functional use of the hand(s). Functional use of hand, or manual ability can be measured by this questionnaire. However, it has no participation items [31]. Items are answered on a 4-point Likert scale, that 4 is considered as “easy performing” and 0 as “never do”. The overall score is scaled from 0 (most sever disability) to 64 (no disability).

-

5)

The patient’s outcome of surgery hand/arm (POS-Hand arm) [36] was designed specifically to evaluate the outcome of surgery [35]; [28]. It can be used before and after surgery to evaluate grip strength and range of motion. It includes 29 items that create three scales: physical activity (12 items), symptom (12 items), psychological functioning and cosmetic appearance (5 items). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The overall score is scaled from 0 to 100 and are calculated by formula. Summing the items generates three summary scale scores. Then, these scores are transformed to a 0–100 scale. Higher score indicates better health.

-

6)

ABILHAND [37] was developed as a Rasch-built measure to measure manual ability. It includes 23 items and is scored as 4-point likert scale, that 0 is considered as no activity and 4 as fully and easily performing activity. It considers ability as the capacity of a person as a whole to execute activities. It was designed with a simple layout with items in a visual analogue form. Items include extended activities of daily living, such as cooking, office work, and handiwork. The overall score is scaled from NA (not applicable), 0 (most sever disability) to 46 (no disability).

-

7)

Patient evaluation measure (PEM) [38, 39] was developed to assess outcome of treatment in a visual analogue form. It contains three domains: 1) treatment with 5 items, 2) profile of hand health with 11 items, and 3) overall assessment with 3 items. Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale from that 1 is considered as strong or normal and 7 is considered as weak or absent result. The PEM score is calculated by summing the values for each item in subscales two and three and expressing it as a percentage of maximum possible score (0–98 that the higher score means the higher disability).

Linking to ICF

In the next step, the selected items of measures were linked to ICF hand Core Set. Hand Core set contains 117 components and 38 (32 %) of them refer to the Activities and Participation category [40]. This category was chosen to evaluate disability. The result has been shown in Tables 2 and 3. It provides a propitiate view on the extent they matched with the framework of the ICF hand Core Set. The Linking was done based on the rules of linking [41, 42].

Table 2.

Linking outcome measures to Disability (activity and participation) category of ICF Hand Core Set

| Codes | Activity and participation | DASH | MHQ | MAM16 | POS | HAT | ABILHAND | PEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d170 | Writing | 2 | 16 | 2h | 1 | |||

| d230 | Carrying out daily routine | 23,9 | 8b | |||||

| d360 | Using communication devices and techniques | 10 | 2d | |||||

| d410 | Changing basic body position | |||||||

| d420 | Transferring oneself | |||||||

| d430 | Lifting and carrying objects | 10 | 24 | 9 | ||||

| d4400 | Picking up | 17,12 | 2 | 2a | ||||

| d4401 | Grasping | 13,18 | 2h2 | 4 | 7b | |||

| d4402 | Manipulating | 16 | 14,19,22 | 3,4,5,10,11,12,14 | 2b | 2,6 | 1,3,6,7,10,11,12,14,15,16,20 | |

| d4403 | Releasing | |||||||

| d4408 | Fine hand use, other specified | 27 | 8,9 | 2d | 2 | 2,3,4,7,8,16,17,18,19 | ||

| d4450 | Pulling | |||||||

| d4451 | Pushing | 5 | ||||||

| d4452 | Reaching | 6 | ||||||

| d4453 | Turning or twisting the hands or arms | 1,3,12 | 11,16,21 | 12,13,7 | 2c,2f,2g2,2g,2i | 3,7,5 | 1,5,8,9,13 | |

| d4454 | Throwing | |||||||

| d4455 | Catching | |||||||

| d4458 | Hand and arm use, other specified | 12,14 | 6,15 | 5,6,7,11,13,14,17,18 | ||||

| d455 | Moving around | |||||||

| d465 | Moving around using equipment | |||||||

| d470 | Using transportation | 20 | ||||||

| d475 | Driving | |||||||

| d510 | Washing oneself | 13,14 | 26 | 20 | ||||

| d520 | Caring for body parts | |||||||

| d530 | Toileting | 2j | 8 | |||||

| d540 | Dressing | 15 | 2e,2f | 10,12,16,18 | ||||

| d550 | Eating | 23 | 1 | |||||

| d560 | Drinking | |||||||

| d570 | Looking after one’s health | |||||||

| d620 | Acquisition of goods and services | |||||||

| d630 | Preparing meals | 4 | ||||||

| d640 | Doing housework | 23,7 | 25 | 8b | ||||

| d650 | Caring for household objects | |||||||

| d660 | Assisting others | |||||||

| d7 | Interpersonal interactions and relationships | 22,21 | ||||||

| d810/ d839 | Education | |||||||

| d840/ d859 | Work and employment | 23,4w,3w, 2w,1w | 1-5w | 9b | ||||

| d920 | Recreation and leisure | 17,18,19,1s,2s,3s,4s | 13 |

30 of 38 DASH (78 %) to 16 (42 %)ICF disabilities

20 of 37(54 %) MHQ to 10(26 %) ICF disabilities

All of MAM-16 to 8(21 %) ICF disabilities

12 of 29(41 %) POS to 9(23 %) ICF disabilities

10 of 14(71 %) HAT to 7 (18 %)ICF disabilities

All of ABIL HAND (20 ta manual ability in RA) to 6(16 %) ICF disabilities

4 of 19 PEM to 4 ICF disabilities

Table 3.

Percent of items linked to ICF and ICF components are covered by measure

| Items linked | ICF covering | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | N | % | N | % |

| DASH | 30 | 78 | 16 | 42 |

| MHQ | 20 | 54 | 10 | 26 |

| HAT | 10 | 71 | 7 | 18 |

| MAM-16 | 16 | 100 | 8 | 21 |

| POS-hand/arm | 12 | 41 | 9 | 23 |

| PEM | 4 | 21 | 4 | 10 |

| ABILHAND | 23 | 100 | 6 | 16 |

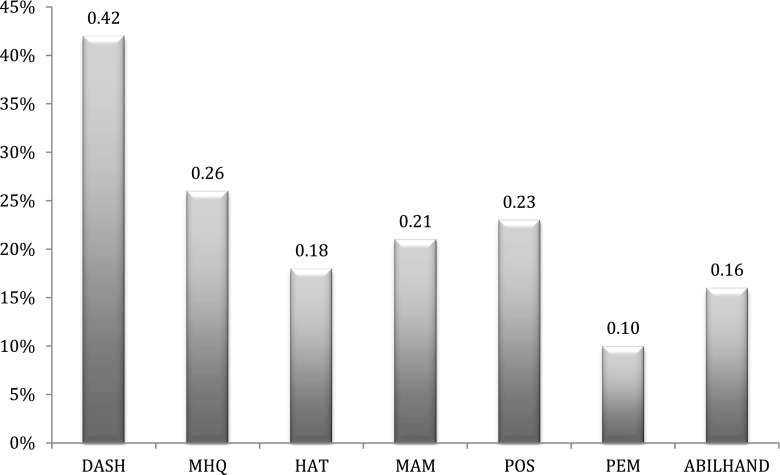

As shown in Table 3, DASH, MAM-16, POS Hand/Arm, MHQ, HAT linked to 16 components (42 %), to 8 components (21 %), 9 components (23 %), 10 components (26 %), 7 components (18 %) of ICF hand Core Set categories of activity and participation respectively. DASH and MHQ had the most covering to ICF hand Core Set part of activity and participation (Fig. 1). They are evaluating disability but not its entire domain.

Fig. 1.

Percent of ICF components covered by hand measurres

All of the items of ABILHAND and MAM-16 were covered by ICF components. In other measures, out of 38 items of DASH, 30 items (78 %), out of 37 of MHQ,20 items (54 %), out of 19 items of PEM, 4 items (21 %), out of 14 items of HAT, 10 items (71 %) , and out of 29 items of POS-HAND, 12 items (41 %) linked to ICF hand Core Set components of activity and participation categories.

16 (42 %) components of activity and participation of ICF hand Core Set were not considered in outcome measures (Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

The aim of this review was to find out the non disease specified outcome measures used in hand injuries to assess disability based on ICF(which considered as activity limitation and participation restriction) [43–45] and to evaluate to what extent their items linked with components of activity and participation category of ICF hand Core Set.

The review showed there is seven patient-report non-disease specified measures that are being used to access the disability in hand conditions; (DASH, MAM-16, POS Hand/Arm, MHQ, HAT, PEM, ABILHAND). The main results of this study can be categorised in three domains:

None of the measures are linked with all components of ICF.

The items in the measures that are not linked with activity and participation category of ICF, either belong to the other catgories or don’t link with ICF at all.

ICF contains some components that are not covered by any of the measures.

All of the measures only linked to 16 out of 38 (42 %) components of activity and participation from hand Core Set. DASH has the most (42 %) and PEM the least (10 %) linking to ICF components. The measures consider disability as activity limitation and participation restriction, therefore they do not merely assess disability. Previous studies conducted to link hand outcome measures [23, 46] in upper extremity also showed that none of them were fully linked to ICF. Furthermore, results of this study is in concurrence with other studies indicated that the most components of ICF addressed in the outcome measures are about activity [47] which is defined as the execution of a task or action( for example ABILHAND, MAM-16). Although, all the items of those measures are fully linked to ICF, but they only linked to 6 components of activity and participation. As their content mostly address task from ABILHAND (open a jar) and manual ability from Mam-16( buttoning a shirt), they cover the activity parts of ICF.

The second result, showed that the activity limitations and participation restrictions are not yet fully considered by the measures. The measures contain items that can be linked to the body function and structure of ICF categories, for example “arm shoulder and pain” (DASH) and “how did your fingers move?” (MHQ) or environmental and personal factors, for example “ I was satisfied with appearance of my hand” (MHQ), Which are not considered as disability [48]. These results are supported by several studies [47, 49], which indicate that most of the outcome measures that are being used in hand therapy and surgery assess the body function and structure domains of ICF [17]. Most frequently research addressed in Body Functions, which consistent with studies on conditions such as hand osteoarthritis, scleroderma, Dupuytren’s contracture, systemic lupus erythematous, or digit amputations[11, 17, 50]. Although these aspects of functioning are important to be measured, but based on ICF, they are not considered as disability [51].

The final result indicated that ICF contains some of components from activity and participation category, which not considered in measures, like; Changing basic body position (d410), Catching (d4455) Preparing meals (d630) Moving around using equipment (d465). Reviewing the content of the ICF components that are not considered in measures, indicated that most of them which focused on the concepts (assisting others; d660, doing house work; d640) could be defined as participation. Also, based on ICF texonomy involvement in life situation is considered as participation [52]. Moreover, [44] participation is performing roles in the domains of social functioning, family, home, financial, work/education, or in a general domain.

Although, the ICF has defined activity and participation separately, they are considered as one category. It makes it difficult to clearly operationalize these different concepts in measurements [44, 53].

As impairment can be considered at the organ level, disability at the person level and handicapped at the social level [54], it is ideal to distinguish activity and participation meanings in ICF coding, e.g. a patient with a ulnar nerve lesion will have difficulties in doing key pinch activity and in this level he is disable, but based on personal (i.e. motivation) and environmental factors (i.e. using splint) he may or not have difficulty in opening the door with a key, that is done in social level and indicates his participation. The relation between impairment and activity limitation and participation restriction can show the efficiency of treatment, as the final goal of rehabilitation is ability in spite of impairments.

There appears to be no consensus on appropriate instruments to assess disability in patients with hand injuries [55]. It can be due to disagreement on defining disability. It is ideal to distinguish activity and participation components to know disability in personal level and social level [53]. This distinction can lead to the stablishment of the relation between impairment in organs with disability in personal or social level.

Therefore, controversies in disability definition were the most challenging parts of this study. Also, lack of distinction between activity and participation makes it difficult to identify that which one of them can be the direct consequence of impairments and wether both of them are affected by social and personal factors or not. It is preferred to characterize activity and participation to know appropriate description of disability and handicapped.

Acknowledgements

Authors are very grateful to Dr. David Ring associated professor of Harvard University for his valuable comments and feedbacks.

This review is part of PhD thesis about developing an ICF based disability questionaire in hand injuerd person.

Contributor Information

Maryam Farzad, Phone: +98-21-22180063, http://www.uswr.ac.ir.

Fereydoun Layeghi, Email: drlayeghi@yahoo.com.

Ali Asgari, http://www.khu.ir.

References

- 1.Lovett BJ (2012) Testing accommodations under the Amended Americans with disabilities act: the voice of empirical research. J Disab Pol Stud

- 2.Bot AG, Ring DC. Recovery after fracture of the distal radius. Hand Clin. 2012;28(2):235. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteneck G, Dijkers MP. Difficult to measure constructs: conceptual and methodological issues concerning participation and environmental factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11):S22–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Geneva (1994) International classification of impairments, disabilities, and handicaps: A manual of classification relating to the consequences of disease. (9241541261). ERIC Clearinghouse

- 5.Threats TT (2012) WHO‚ Äôs international classification of functioning, disability, and health: a framework for clinical and research outcomes. Outcomes in Speech-Language Pathology: Contemporary Theories, Models, and Practices

- 6.Nagi SZ (1976) An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. The Milbank Memorial Fund quarterly. Health and society, 439–467 [PubMed]

- 7.Jette AM. Toward a common language of disablement. J Gerontol A: Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(11):1165–1168. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ICF, WHO (2001) International classification of functioning, disability and health

- 10.Linton SJ. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine. 2000;25(9):1148–1156. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boonen A, Maksymowych WP. Measurement: function and mobility (focussing on the ICF framework) Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(5):605–624. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum P, Stewart D (2004) The World Health Organization international classification of functioning, disability, and health: A model to guide clinical thinking, practice and research in the field of cerebral palsy. Paper presented at the Seminars in Pediatric Neurology [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.er Disler Pet (1984) DISABILITY AND HANDICAP. to discuss approaches to the management of poverty, nor to provide a comprehensive text for the medically qualified; neither is this a guide line for people afflicted by both poverty and illness (many of whom would anyway be illiterate by virtue of their economic status). 87

- 14.Cieza A, Ewert T, Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G (2004) Development of ICF core sets for patients with chronic conditions. J Rehabil Med-Suppl 9–11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kus S, Oberhauser C, Cieza, A (2012) Validation of the brief international classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF) core set for hand conditions. J Hand Ther [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Chapman TT, Richard RL, Hedman TL, Renz EM, Wolf SE, Holcomb JB. Combat casualty hand burns: evaluating impairment and disability during recovery. J Hand Ther. 2008;21(2):150–159. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindra RR, Dias JJ, Heras-Palau C, Amadio PC, Chung KC, Burke FD. Assessing outcome after hand surgery: the current state. J Hand Surg Br Eur Vol. 2003;28(4):289–294. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(03)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlsson IK, Edberg AK, Wann-Hansson C. Hand-injured patients’ experiences of cold sensitivity and the consequences and adaptation for daily life: a qualitative study. J Hand Ther. 2010;23(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grunert BK, Devine CA, Matloub HS, Sanger JR, Yousif NJ, Anderson RC, Roell SM. Psychological adjustment following work-related hand injury: 18-month follow-up. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29(6):537. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafsson M, Ahlström G. Emotional distress and coping in the early stage of recovery following acute traumatic hand injury: A questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(5):557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jerosch-Herold C, Mason R, Chojnowski AJ. A qualitative study of the experiences and expectations of surgery in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Ther. 2008;21(1):54–62. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson TJ, Björnstig U. Persistent medical problems and permanent impairment five years after occupational injury. Scand J Public Health. 1995;23(2):121–128. doi: 10.1177/140349489502300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velstra IM, Ballert CS, Cieza A. A systematic literature review of outcome measures for upper extremity function using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health as reference. PM&R. 2011;3(9):846–860. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franchignoni F, Giordano A, Ferriero G. On dimensionality of the DASH. Mult Scler J. 2011;17(7):891–892. doi: 10.1177/1352458511406909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franchignoni F, Giordano A, Sartorio F, Vercelli S, Pascariello B, Ferriero G. Suggestions for refinement of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure (DASH): a factor analysis and Rasch validation study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(9):1370–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Oosterom FJT, Ettema AM, Mulder PGH, Hovius SER. Impairment and disability after severe hand injuries with multiple phalangeal fractures. J Hand Surg. 2007;32(1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C, Beaton D, Cole D, Davis A, Marx RG. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Head) Am J Indust Med. 1996;29(6):602–608. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van de Ven-Stevens L, Munneke M, Spauwen PHM, van der Linde H. Assessment of activities in patients with hand injury: a review of instruments in use. Hand Ther. 2007;12(1):4–14. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung KC, Hamill JB, Walters MR, Hayward RA. The Michigan hand outcomes questionnaire (MHQ): assessment of responsiveness to clinical change. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42(6):619. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199906000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung KC, Pillsbury MS, Walters MR, Hayward RA. Reliability and validity testing of the Michigan hand outcomes questionnaire. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(4):575. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naidu SH, Panchik D, Chinchilli VM. Development and validation of the hand assessment tool. J Hand Ther. 2009;22(3):250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alderman AK, Chung KC. Measuring outcomes in hand surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35(2):239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giladi AM, Chung KC (2012) Measuring outcomes in hand surgery. Clin Plast Surg [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Novak CB, Anastakis DJ, Beaton DE, Katz J. Patient-reported outcome after peripheral nerve injury. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(2):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CC, Granger CV, Peimer CA, Moy OJ, Wald S. Manual Ability Measure (MAM-16): a preliminary report on a new patient-centred and task-oriented outcome measure of hand function. J Hand Surg: Br Eur Vol. 2005;30(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cano SJ, Browne JP, Lamping DL, Roberts AHN, McGrouther DA, Black NA. The patient outcomes of surgery-hand/arm (POS-hand/arm): A new patient-based outcome measure. J Hand Surg: Br Eur Vol. 2004;29(5):477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penta M, Thonnard J-L, Tesio L. ABILHAND: a Rasch-built measure of manual ability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(9):1038–1042. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dias JJ, Bhowal B, Wildin CJ, Thompson JR. Assessing the outcome of disorders of the hand is the patient evaluation measure reliable, valid, responsive and without bias? J Bone Jt Surg Br Vol. 2001;83(2):235–240. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.10838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macey AC, Burke FD, Abbott K, Barton NJ, Bradbury E, Bradley A, Brown P. Outcomes of hand surgery. J Hand Surg: Br Eur Vol. 1995;20(6):841–855. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(95)80059-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coenen M, Cieza A, Stamm TA, Amann E, Kollerits B, Stucki G. Validation of the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) core set for rheumatoid arthritis from the patient perspective using focus groups. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(4):R84. doi: 10.1186/ar1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cieza A, Brockow T, Ewert T, Amman E, Kollerits B, Chatterji S, Stucki G. Linking health-status measurements to the international classification of functioning, disability and health. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34(5):205–210. doi: 10.1080/165019702760279189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stucki G. ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:212–218. doi: 10.1080/16501970510040263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: WHO; 2002. pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perenboom RJM, Chorus AMJ. Measuring participation according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(11–12):577–587. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000137081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whiteneck G (2006) Conceptual models of disability: past, present, and future. Paper presented at the Workshop on disability in America: A new look

- 46.Silva DA, Ferreira SR, Cotta MM, Noce KR, Stamm TA. Linking the disabilities of arm, shoulder, and hand to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health. J Hand Ther: Off J Am Soc Hand Ther. 2007;20(4):336. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metcalf C, Adams J, Burridge J, Yule V, Chappell P. A review of clinical upper limb assessments within the framework of the WHO ICF. Musculoskeletal Care. 2007;5(3):160–173. doi: 10.1002/msc.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jette AM. Toward a common language for function, disability, and health. Phys Ther. 2006;86(5):726–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szabo RM. Outcomes assessment in hand surgery: when are they meaningful? J Hand Surg. 2001;26(6):993–1002. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2001.29487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chung KC, Burns PB, Davis Sears E. Outcomes research in hand surgery: Where have we been and where should we go? J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(8):1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kjeken I, Dagfinrud H, Slatkowsky-Christensen B, Mowinckel P, Uhlig T, Kvien TK, Finset A. Activity limitations and participation restrictions in women with hand osteoarthritis: patients‚Äô descriptions and associations between dimensions of functioning. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(11):1633–1638. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Organization World Health (2001) International classification of functioning disability and health (ICF)

- 53.Jette AM, Haley SM, Kooyoomjian JT. Are the ICF activity and participation dimensions distinct? J Rehabil Med. 2003;35(3):145–149. doi: 10.1080/16501970310010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Badley EM. Enhancing the conceptual clarity of the activity and participation components of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2335–2345. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schoneveld K, MsC PT (2009) Clinimetric evaluation of measurement tools used in hand therapy to assess activity and participation. Practice 1:2 [DOI] [PubMed]