Abstract

Context:

Lifestyle factors such as tobacco smoking and alcohol use can affect the presentation and course of psoriasis. There is a paucity of data on this subject from India.

Aims:

To find out whether increased severity of psoriasis in adult Indian males is associated with tobacco smoking and alcohol use.

Settings and Design:

Cross-sectional study in the Department of Dermatology of a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital.

Subjects and Methods:

Male patients above 18 years of age attending a psoriasis clinic between March 2007 and May 2009 were studied. Severity of psoriasis (measured using Psoriasis Area and Severity Index – PASI) among smokers and non-smokers was compared. We also studied the correlation between severity of psoriasis and nicotine dependence (measured using Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence) and alcohol use disorders (measured using Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–AUDIT).

Statistical Analysis:

Z-test, Odd's ratio, Chi-square test, Spearman's correlation coefficient.

Results:

Of a total of 338 patients, 148 were smokers and 173 used to consume alcohol. Mean PASI score of smokers was more than that of non-smokers (Z-test, z = −2.617, P = 0.009). Those with severe psoriasis were more likely to be smokers (χ2 = 5.47, P = 0.02, OR = 1.8, Confidence Interval 1.09-2.962). There was a significant correlation between PASI scores and Fagerström score (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.164, P < 0.01). Mean PASI scores of persons who used to consume alcohol and those who did not were comparable.(Z-test, z = −0.458, P = 0.647). There was no association between severity of psoriasis and alcohol consumption.(χ2 = 0.255, P = 0.613, Odds Ratio = 1.14, CI 0.696-1.866). There was no correlation between PASI scores and AUDIT scores (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.024, P > 0.05).

Conclusions:

Increased severity of psoriasis among adult males is associated with tobacco smoking, but not with alcohol use.

Keywords: Alcohol drinking, psoriasis, severity, smoking

Introduction

What was known?

Only a few studies have been conducted on the association of smoking and alcohol use with severity of psoriasis.

They do not provide conclusive evidence.

Psoriasis is best viewed as a multi-factorial disease where there is an interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Importance of lifestyle factors such as smoking and alcohol use in its pathogenesis are being increasingly recognized.[1,2] Several studies have shown an association between smoking and psoriasis.[3,4,5,6,7] Alcohol consumption also has been reported to increase the risk of developing psoriasis.[5,8,9] However, there have been only a few published studies on the association of smoking[10,11] and alcoholism[12,13] with increased severity of psoriasis. Conclusions of various studies have differed, probably due to geographic and gender differences.[14] There are no studies on this subject from the Indian subcontinent. Hence, we decided to conduct a study on the relationship between the clinical severity of psoriasis with tobacco smoking and alcohol use.

Subjects and Methods

The setting of the study was a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in the public sector in the South Indian state of Kerala. The Department of Dermatology and Venereology conducts a twice-weekly clinic to provide care and support to patients with psoriasis. All patients who attend this clinic are systematically evaluated by either one of the first two authors with post-graduate degree in dermatology. We recorded the socio-demographic and clinical details in a specially designed proforma. Consecutive patients who attended the clinic between March 2007 and May 2009 participated in this cross-sectional study subject to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criterion was a definite diagnosis of psoriasis. The diagnosis was primarily clinical, supported by histopathology if required. Those less than 18 years of age and all females were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was taken from all patients.

We assessed the clinical severity of psoriasis using Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), on the first visit itself. History of tobacco smoking was taken. Patients were classified as smokers and non-smokers. The latter group included never smokers and past smokers (those who quit smoking at least 1 year earlier). We scored the intensity of smoking using Fagerström test for nicotine dependence.[15] This test is designed to assess the impact of nicotine use on the daily lives of patients. It has a range of scores between 0 and 10.

We also classified patients into those who used to consume alcohol and those who did not. Alcohol users included those who consumed alcohol daily or occasionally. Non-users included those who have never taken alcoholic drinks in the past and those who stopped consuming alcohol at least 1 year earlier. A score was calculated on harmful alcohol consumption using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).[16] This test has a range of scores from 0 to 40.

The Z-test was used to compare PASI scores of smokers and non-smokers as well as drinkers and non-drinkers. Patients were divided into four quartiles based on the severity of psoriasis as denoted by their PASI score. Patients with PASI score above the third quartile were defined as those with more-severe psoriasis and the others as less-severe psoriasis. Smoking and alcohol use status of those with more-severe psoriasis were compared with those with less-severe psoriasis using the Chi-square test. Furthermore, the mean Fagerström score and AUDIT score of those with more-severe psoriasis were compared with those with less-severe psoriasis using the Z-test. A P < 0.05 was considered significant in the statistical analysis. Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to identify any correlation between the PASI score and Fagerström score as well as between the PASI score and the AUDIT score.

Results

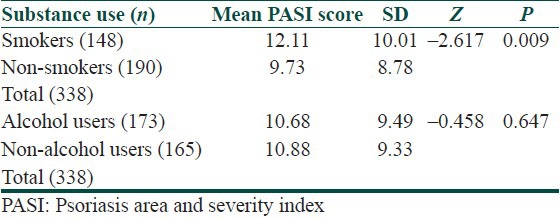

Out of the total 500 patients who attended the clinic during the study period, 338 patients who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the study. Those excluded consisted of 148 females and 14 males younger than 18 years of age. The age of the participants varied from 20 years to 80 years. Chronic plaque type of psoriasis was the commonest type (303/338; 89.64%). There were 148 smokers and 190 non-smokers. A total of 173 patients used to consume alcohol, whereas 165 did not. The mean PASI score was 12.11(SD 10.01) among smokers and 9.73 (SD 8.78) among non-smokers. (Z-test, z = −2.617, P = 0.009). [Table 1]. The mean PASI score was 10.68 (SD 9.49) among those who used alcohol and 10.88 (SD 9.33) among non-users. (Z-test, z = −0.458, P = 0.647).

Table 1.

Mean psoriasis area and severity index scores in relation with smoking and alcohol use

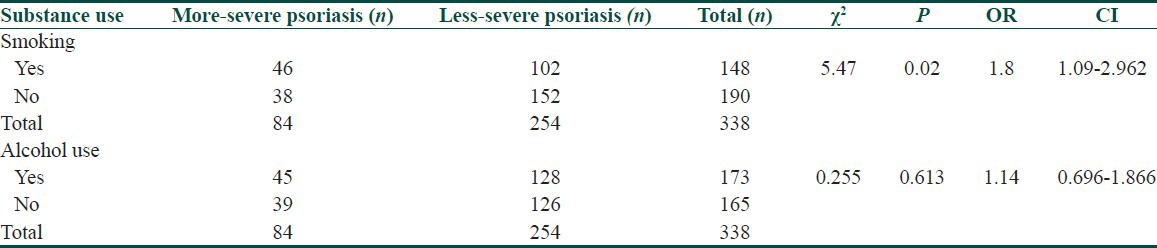

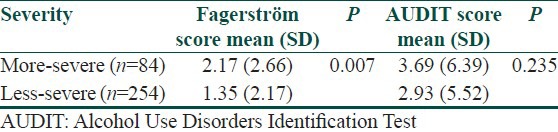

Eighty-four patients who had PASI above the third quartile were considered to have more-severe psoriasis. Their PASI was 13.88 or more. The remaining 254 patients with PASI scores less than 13.88 were considered to have less-severe disease. There was an association between severity of psoriasis and smoking status (χ2 = 5.47, P = 0.02, OR = 1.8 with CI[1.09, 2.962]), whereas there was no association between severity of psoriasis and alcoholic status. (χ2 = 0.255, P = 0.613, OR = 1.14, CI 0.696, 1.866) [Table 2]. Mean Fagerström scores of 84 patients with more-severe psoriasis was 2.17 (SD 2.66) whereas that of 254 patients with less-severe psoriasis was 1.35 (SD 2.17) (Z-test, z = −2.711, P = 0.007) [Table 3]. Mean AUDIT scores of 84 patients with more-severe psoriasis was 3.69 (SD 6.39) whereas that of 254 patients with less-severe psoriasis was 2.93 (SD 5.52) (Z-test, z = −1.186, P = 0.235).

Table 2.

Association of smoking and alcohol use with severity of psoriasis

Table 3.

Relationship between severity of psoriasis with Fagerström score and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test score

There was a positive correlation between PASI scores and Fagerström scores (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.164, P < 0.01). There was no correlation between PASI scores and AUDIT scores (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.024, P > 0.05).

Discussion

Our findings revealed that the severity of psoriasis was more among smokers than among non-smokers. There was a positive correlation between nicotine dependence and severity of psoriasis. However, there was no association between alcohol use and severity of psoriasis.

There was an early report that cigarette smoking in men was associated with severity of psoriasis of the extremities.[17] Subsequently, an Italian study reported that cigarette smoking significantly increased the risk of clinically more-severe psoriasis.[10] Another study from Germany also reported a similar association.[5] A recent Swedish population-based case-control study showed an association between smoking and onset of psoriasis, but not with severity of disease.[11] The present report is the first one from India providing information on this subject.

The results of this study do not show an association between alcohol use and severity of psoriasis. In fact, the mean PASI score of those who used to consume alcohol was slightly lower than those who did not, though it was not statistically significant. There was an early report that severity of psoriasis was associated with alcohol use.[12] A population-based study from Sweden did not show an association between alcohol use and severity of psoriasis, although there was an association with onset of psoriasis among males.[11] A study from Germany showed association between alcohol use and severity of psoriasis in females, but not in males.[5] A recent UK study reported a modest association between weekly alcohol consumption and self-reported physical severity of psoriasis.[13]

While most of the previous studies used direct measures of smoking and alcohol use such as cigarette-years and number of drinks per day, we used Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence and AUDIT, respectively. These tools not only provide a measure of the intensity of substance use but also assess their impact on daily lives of patients and dependence. The quantitative data provided by them also enabled us to study the correlation between substance use and severity of psoriasis. Our findings revealed a positive correlation with nicotine dependence, whereas there was no correlation with alcohol use disorders.

The effect of smoking on psoriasis severity has been reported to be more among women.[10] Such an analysis was not possible in our study as we studied only adult males. The reason for excluding females in our study was the rarity of smoking and alcohol use among women in the Indian population.[18] None of the females or children attending our psoriasis clinic were smokers and only one female gave history of mild alcohol use.

Smoking could increase the release of chemotactic factors.[19] It also induces the overproduction of various mediators of inflammation.[20] These factors could play a role in the onset of psoriasis among susceptible individuals and may also increase its severity. It is also possible that a lowered quality of life, emotional problems, and difficulties in family life and social life may lead some patients to take to the habit of tobacco smoking.[21]

There are some limitations to our study. The cross-sectional design prevented us from concluding whether smoking is a cause or an effect of severe psoriasis. Similarly, the association with nicotine dependence demonstrated by us also could be because psoriatic patients take to smoking more than non-psoriatic patients. These questions can be answered by future studies using case-control or cohort designs. It may be possible that the presence of occasional smokers and alcohol users might have influenced the results of the comparison studies. However, as these people were part of the substance-using group, it would have resulted only in masking of an existing association. Despite this possible masking, the association with smoking is impressive in our study. However, it is possible that inclusion of occasional users might have masked an existing association with alcohol use. Another limitation is that, it is hard to generalize the findings of a hospital-based study to the community. This requires further population-based studies.

Despite these limitations, this study provides evidence that smoking, but not alcohol use, is associated with increased severity of psoriasis among adult male patients. Moreover, there is a demonstrable association between the severity of psoriasis with nicotine dependence. This should prompt researchers to generate further evidence on this topic of considerable public health importance. Meanwhile, it should alert clinicians about the modifiable lifestyle risk factors of patients with psoriasis.

What is new?

Smoking is associated with increased severity of psoriasis among adult males while alcohol use is not.

First published study on the topic from Indian subcontinent.

First study linking the effect of nicotine use on daily life of patients with severity of psoriasis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Naldi L. Epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2004;3:121–8. doi: 10.2174/1568010043343958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raychaudhuri SP, Gross J. Psoriasis risk factors: Role of lifestyle practices. Cutis. 2000;66:348–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, Papenfuss J, Hansen CB, Callis KP, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527–34. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, Belloni Fortina A, Peserico A, Virgili AR, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: Results from an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerdes S, Zahl VA, Weichenthal M, Mrowietz U. Smoking and alcohol intake in severely affected patients with psoriasis in Germany. Dermatology. 2010;220:38–43. doi: 10.1159/000265557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bø K, Thoresen M, Dalgard F. Smokers report more psoriasis, but not atopic dermatitis or hand eczema: Results from a Norwegian population survey among adults. Dermatology. 2008;216:40–5. doi: 10.1159/000109357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Wang H, Te-Shao H, Yang S, Wang F. Frequent use of tobacco and alcohol in Chinese psoriasis patients. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:659–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poikolainen K, Reunala T, Karvonen J, Lauharanta J, Kärkkäinen P. Alcohol intake: A risk factor for psoriasis in young and middle aged men? BMJ. 1990;300:780–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6727.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jankovic S, Raznatovic M, Marinkovic J, Jankovic J, Maksimovic N. Risk factors for psoriasis: A case-control study. J Dermatol. 2009;36:328–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Leffondré K, Sampogna F, Melchi F, Mazzotti E, et al. Relationship between smoking and the clinical severity of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1580–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolk K, Mallbris L, Larsson P, Rosenblad A, Vingård E, Ståhle M. Excessive body weight and smoking associates with a high risk of onset of plaque psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:492–7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monk BE, Neill SM. Alcohol consumption and psoriasis. Dermatologica. 1986;173:57–60. doi: 10.1159/000249219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirby B, Richards HL, Mason DL, Fortune DG, Main CJ, Griffiths CE. Alcohol consumption and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:138–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins E. Alcohol, smoking and psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:107–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption - II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Watteel GN. Cigarette smoking in men may be a risk factor for increased severity of psoriasis of the extremities. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:859–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb03909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugathan TN, Soman CR, Sankaranarayanan K. Behavioural risk factors for non communicable diseases among adults in Kerala, India. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:555–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonnex TS, Carrington P, Norris P, Greaves MW. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte random migration and chemotaxis in psoriatic and healthy adult smokers and non-smokers. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119:653–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryder MI, Saghizadeh M, Ding Y, Nguyen N, Soskolne A. Effects of tobacco smoke on the secretion of interleukin-1beta, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and transforming growth factor-beta from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2002;17:331–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2002.170601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chodorowska G, Kwiatek J. Psoriasis and cigarette smoking. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska Med. 2004;59:535–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]