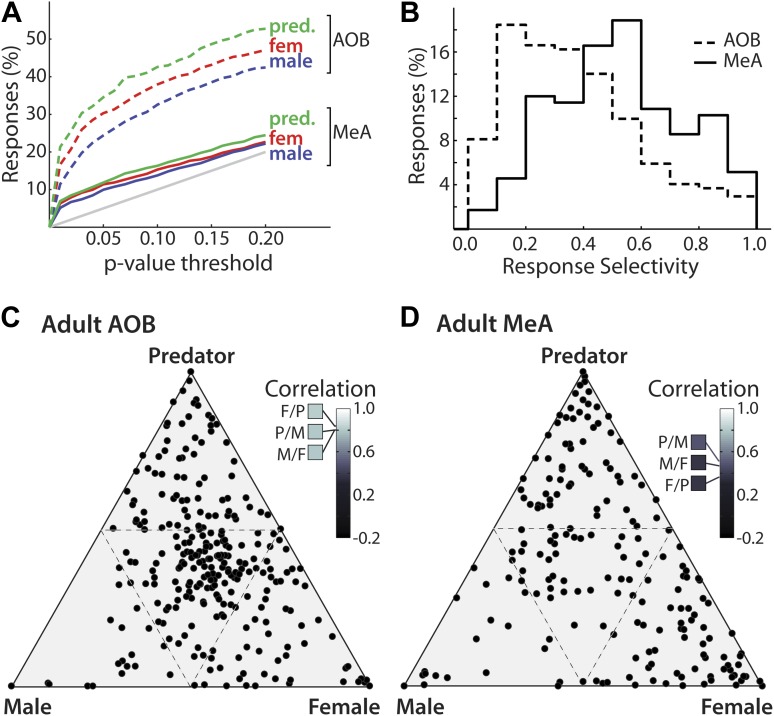

Figure 3. Decreased frequency and increased specificity of sensory responses in the MeA compared to the AOB.

(A) The percentage of single AOB units (dashed curves) and MeA units (solid curves) exhibiting statistically significant responses to male (blue), female (red), and predator (green) vomeronasal stimuli as the threshold for inclusion was varied from p<0 to p<0.2 (abscissa). The diagonal gray line indicates the predicted false positive rate. (B) Distribution of response selectivity (‘Materials and methods’) showing a shift towards higher specificity in MeA (solid line) as compared to the AOB (dashed line). (C) Selectivity of sensory responses for units recorded in the adult AOB (197 units from male and female animals). (D) Selectivity of sensory responses for units recorded in the adult MeA (274 units from male and female animals). Each point represents the response profile of an individual unit, with at least one significant response, to male, predator, and/or female stimuli. Points located near a vertex (more frequent in the MeA) represent units that respond most strongly for the stimulus indicated at that vertex whereas points at the center (more frequent in the AOB) represent units that respond similarly to all stimuli. Insets (C and D) show correlation between responses for each pair of stimuli.