Abstract

In the mammalian central nervous system only γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine have been firmly linked to inhibition of neuronal activity through increases in membrane Cl- conductance, and these responses are mediated by ionotropic receptors. Iontophoretic application of histamine can also cause inhibitory responses in vivo, although the mechanisms of this inhibition are unknown and may involve pre- or postsynaptic factors. Here, we report that application of histamine to the GABAergic neurons of the thalamic perigeniculate nucleus (PGN), which is innervated by histaminergic fibers from the tuberomammillary nucleus of the hypothalamus, causes a slow membrane hyperpolarization toward a reversal potential of -73 mV through a relatively small increase in membrane conductance to Cl-. This histaminergic action appears to be mediated by the H2 subclass of histaminergic receptors and inhibits the single-spike activity of these PGN GABAergic neurons. Application of histamine to the PGN could halt the generation of spindle waves, indicating that increased activity in the tuberomammillary histaminergic system may play a functional role in dampening thalamic oscillations in the transition from sleep to arousal.

Histamine (HA)-containing neurons are located in the tuberomammillary complex of the hypothalamus and project to most brain areas, including the thalamus (1, 2). This widely branched system plays a central role in the orchestration of sleep and waking (reviewed in ref. 2). Like other better-studied monoamines of ascending activating systems, HA has been ascribed both excitatory and inhibitory actions in the brain (2-5). Investigations of the cellular mechanisms underlying these actions have revealed four distinct responses. Slow increases in neuronal excitability occur in response to decreases in background-leak K+ conductance, a decrease in the slow after-hyperpolarizing K+ conductance, or an increase in the hyperpolarization-activated mixed cation current, Ih (3, 4). In addition, HA may also reduce or inhibit particular Ca2+ currents, a response that may underlie some inhibitory responses to HA (3, 6). These responses to HA are shared by a wide variety of neuromodulatory transmitters in the brain, which typically control neuronal excitability through the modulation of a broad range of K+, Ca2+, and h-channels (7, 8). Curiously, even though the mammalian brain contains a wide variety of Cl- channels (9), only γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine have been consistently reported to modulate membrane Cl- conductance (reviewed in refs. 7 and 8). In invertebrates HA can also cause neuronal inhibition by increasing membrane Cl- conductance through HA H2 receptors (10-13).

Application of HA to mammalian thalamocortical neurons results in prolonged depolarization through an H1-receptor-mediated decrease in resting K+ conductance and an H2-receptor-mediated enhancement of Ih (4). These depolarizing influences decrease the ability of thalamic networks to generate sleep-related rhythms, such as spindle waves, and increase the ability of transient inputs (such as synaptic potentials) to activate single-spike responses, as occurs in the transition from sleep to waking (14). Histaminergic fibers not only innervate the main relay nuclei of the thalamus, but also the thalamic reticular (nRt) and perigeniculate (PGN) nuclei (15). These GABAergic nuclei act as a feedback and feed-forward inhibitory system in the thalamus and are intimately involved in the generation of at least some forms of sleep-related thalamocortical rhythms (14, 16, 17).

Here, we demonstrate that HA may inhibit both single-spike activity and the generation of spindle waves through an H2-receptor-mediated increase in membrane Cl- conductance in the GABAergic cells of the PGN maintained as a slice in vitro.

Methods

Slice Preparation. For the preparation of slices, male or female ferrets (Mustela putorious furo; Marshall Farms, North Rose, NY), 3- to 4-months-old (for sharp electrode recordings) or 5- to 6-weeks-old (for whole-cell recording), were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (30-40 mg/kg) and killed by decapitation. The forebrain was rapidly removed and 400-μm-thick sagittal slices of the geniculate complex were cut on a vibratome. A modification of the technique developed by Aghajanian and Rasmussen (18) was used to increase tissue viability. During preparation of slices, the tissue was placed in a solution (5°C) in which NaCl was replaced with sucrose while maintaining an osmolarity of 307 mOsm. After preparation, slices were placed in an interface style-recording chamber (Fine Science Tools, Belmont, CA), maintained at 34 ± 1°C, and allowed 2 h to recover. The bathing medium contained 126 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM dextrose; it was aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2 to a final pH of 7.4. For the first 20 min that the thalamic slices were in the recording chamber, the bathing medium contained an equal mixture of the normal NaCl and the sucrose-substituted solutions.

Electrophysiology. Sharp intracellular recording electrodes were formed on a Sutter Instruments P-80 micropipette puller from medium-walled glass (WPI, 1B100F) and beveled on a Sutter Instruments beveler. Micropipettes were filled with 2 M potassium acetate if not otherwise stated. Whole-cell recording pipettes were filled with 145 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes buffer, 2 mM Na2ATP, 0.5 mM Na2GTP, at a final pH of 7.3. Whole-cell recordings were obtained from submerged slices maintained at 34°C.

Only neurons exhibiting a stable resting membrane potential (Vm) negative to -60 mV and electrophysiological properties as reported (19) were included for analysis. Extracellular single or multiunit recordings were obtained by using tungsten electrodes (F. Haer & Co., Bowdoinham, ME). Electrical stimulation of the afferent fibers was achieved through the placement of a concentric stimulating electrode in the optic radiation delivering 10 stimuli (100-μsec duration, 10- to 500-μA amplitude, 100-Hz frequency). Mean values are given ± SEM.

Drug Application. Drugs were either applied through addition to the bathing medium or by the pressure-pulse technique in that a brief (10- to 20-msec, 207- to 345-kPa, 10- to 30-psi) pulse of nitrogen was applied to a broken microelectrode (tip diameter, 2-5 μm) containing the drug dissolved in bathing medium, as described (20). Inhibitory responses to HA were observed with concentrations in the micropipette as low as 1-5 μM. However, we typically used much higher concentrations (250-500 μM) in the pipette so that a very small drop of HA on the surface would give robust effects. When examining the functional effects of HA on spindle-wave generation, we avoided activation of the A-laminae of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (LGNd) by applying picodrops of HA solution only on the side of the PGN nearest to the optic radiation. In ≈33% of extracellularly recorded PGN neurons, the application of HA (5-500 μM) resulted in a weak (e.g., peak change in firing rate of a few Hz) increase in tonic action potential activity (excitatory response) that followed the prolonged (more than tens of seconds) inhibition of tonic activity. This excitatory response was weak, variable, and often not seen with intracellular recordings; therefore, it could not be investigated and is not reported here. All drugs were obtained from Sigma.

Results

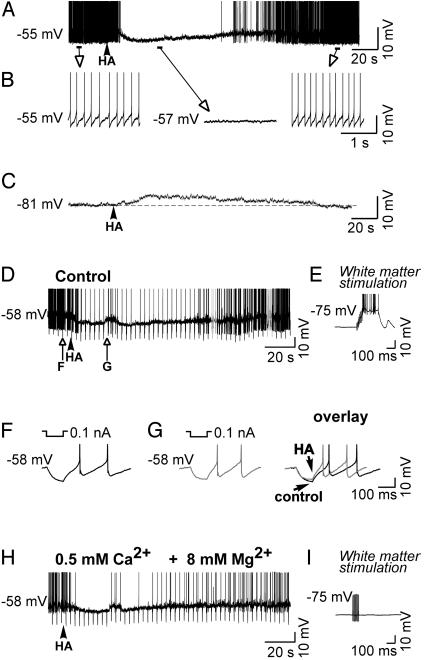

Local picodrop application of HA (5-500 μM in micropipette) to tonically discharging PGN single units recorded extracellularly resulted in a period of inhibition lasting from tens of seconds to >1 min, depending on dose (n = 18; not shown). In similarity with the extracellular recordings, local picodrop application of HA (10-500 μM in micropipette) to intracellularly recorded, tonically discharging PGN neurons resulted in an inhibition of action potential discharge and a slow (>1-min duration) membrane hyperpolarization toward a reversal potential of ≈-73 mV (n = 33; Fig. 1 A and B). If HA was applied while the PGN neuron was hyperpolarized to more negative membrane potentials (e.g., -81 mV; Fig. 1C), the response was reversed and appeared as a slow depolarization. Examination of the electrotonic membrane response to 100-msec duration, 0.01- to 0.5-nA hyperpolarizing current pulses (after compensation for changes in Vm with the intracellular injection of direct current) revealed that HA application resulted in a decrease in apparent input resistance by 19.8 ± 6.1 MΩ (n = 6; Fig. 1 D-G; see also Fig. 4 A-C). To test whether these responses to HA were caused by a direct action on the cell studied or were mediated through the release of another neurotransmitter, we blocked synaptic transmission by local application of tetrodotoxin (10 μM in micropipette; n = 3; not shown) or through bath application of high Mg2+ (8 mM) and low Ca2+ (0.5 mM; n = 3). These manipulations failed to block the HA-induced changes in the membrane potential and the decrease in apparent input resistance (n = 6; Fig. 1H), although the activation of synaptic potentials by orthodromic stimulation of the optic radiation was abolished completely (compare Fig. 1 E and I). We conclude that this inhibitory effect of HA is due to an interaction with receptors located directly on the cell studied and not mediated through a polysynaptic mechanism.

Fig. 1.

HA hyperpolarizes and inhibits tonic action potential activity in perigeniculate GABAergic neurons. (A) Local application of HA results in a slow membrane hyperpolarization and inhibition of tonic action potential activity. (B) Expansion of portions of the recording in A.(C) Application of HA while the neuron was hyperpolarized to -81 mV resulted in a slow membrane depolarization. (D) Response of another PGN cell to the local application of HA, again illustrating the hyperpolarizing, inhibitory response. (E) Response to an orthodromic stimulus of the optic radiation illustrating intact synaptic transmission. (F and G) Expansion of the response to hyperpolarizing current pulses before and after application of HA, illustrating the small decrease in apparent input resistance during the prolonged hyperpolarization. (H) Block of synaptic transmission through bath application of high Mg2+ (8 mM) and low Ca2+ (0.5 mM). This manipulation failed to block the HA-induced hyperpolarization and decrease in apparent input conductance. (I) Response to an orthodromic stimulus of the optic radiation was abolished completely, indicating that normal synaptic transmission was blocked by the high Mg2+, low Ca2+ solution.

Fig. 4.

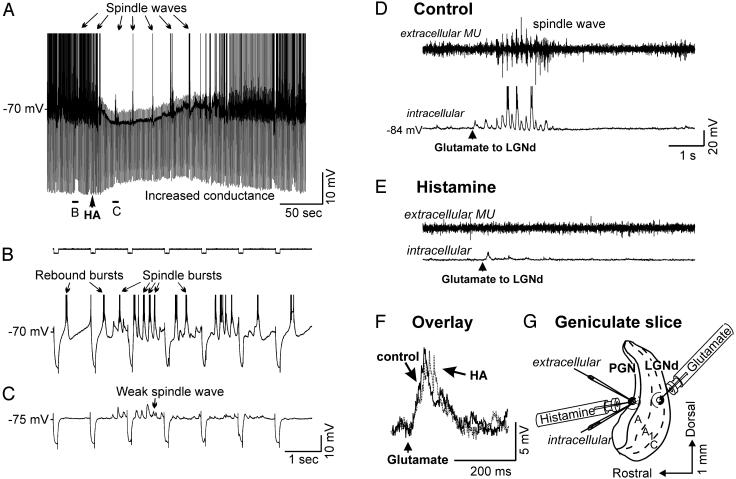

Histamine application to the PGN is able to block or reduce both evoked and spontaneous spindle waves. (A) Local application of HA to this PGN neuron results in a hyperpolarizing response, an increase in membrane conductance, inhibition of rebound burst firing, and a reduction of spindle waves. The cell was injected with hyperpolarizing constant-current pulses (0.2 nA) once every second (see B and C for expansion). After the application of HA, the electrotonic response to the hyperpolarizing current pulse is reduced, and the burst firing is inhibited that is normally triggered by the spindle-wave EPSPs and in response to the hyperpolarizing current pulses. (D) Local application of glutamate (50 μM) to thalamocortical neurons of the A1 lamina with multiunit (MU) extracellular and intracellular recording electrodes placed in the PGN area immediately rostral to the glutamate application site. Activation of the A1 lamina resulted in a barrage of EPSPs followed by a spindle wave in the intracellularly recorded PGN neuron. (E) After local application of HA in the PGN, glutamate activation of lamina A1 still evoked a barrage of EPSPs but not a spindle wave. (F) Overlay of the postsynaptic potentials evoked in the PGN cell by glutamate application in the LGNd before and after application of HA in the PGN. Note that HA does not reduce the evoked EPSPs but abolishes the generation of spindle waves. (G) Illustration of the arrangement of the recording and drug-applying electrodes for the experiment in D-F.

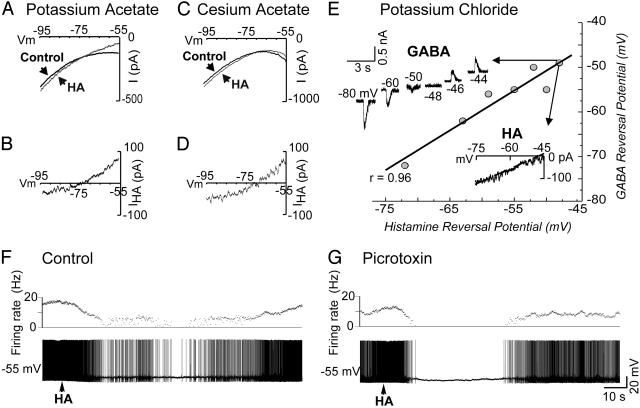

The HA-induced changes in membrane potential could be due to an increase in membrane conductance to K+ or Cl- or a mixed Na+/K+ current or a decrease in a voltage-dependent depolarizing current (that is, Na+ or Ca2+). To distinguish between these possibilities, the properties of the current affected by HA were examined by obtaining I-V plots with the technique of single-electrode voltage clamp before and during the response to local applications of HA and the GABAA agonist muscimol (100 μM in micropipette), which is known to directly activate a Cl- conductance. Application of both drugs resulted in currents that reversed polarity at an average of -72.8 ± 8.5 mV (n = 8; Fig. 2 A and B) for HA and -74.5 ± 7.5 mV (n = 4; not shown) for muscimol in cells recorded with 2 M potassium acetate-filled electrodes. The average conductance change induced by HA was 4.7 ± 0.3 nS (n = 12). In addition, to test whether the current induced by HA may be due to a K+ conductance, PGN neurons were intracellularly loaded with the K+ channel blocker cesium. In cells recorded with 3 M cesium acetate-filled electrodes, a manipulation known to block or reduce transmitter-induced increases in K+ conductance in thalamic neurons (20), application of HA still induced a current that reversed at -74.6 ± 3.4 mV (n = 3; Fig. 2 C and D). These results strongly support the hypothesis that activation of histaminergic receptors in PGN/nRt neurons may result in an increase in a Cl-, but not a K+, conductance.

Fig. 2.

Voltage characteristics of the ionic responses to HA in PGN neurons recorded with electrodes loaded with potassium acetate, cesium acetate, or potassium chloride by using single-electrode voltage clamp. (A) Current versus voltage (I-V) plot before and during the response to HA obtained with a neuron recorded with an electrode loaded with 2 M potassium acetate. (B) Subtracting control trace from HA trace reveals the voltage dependence of the HA-induced current and its reversal potential, which averaged -72.8 ± 8.5 mV (SD, n = 8) across neurons. (C) I-V plot before and during the response to HA obtained with a neuron recorded with 3 M cesium-acetate-filled electrodes. (D) Subtracting control traces from HA traces reveals the voltage dependence of the currents and their reversal potential with a current that reversed on average at -74.6 ± 3.4 mV across neurons. (E) Plot of reversal potentials for GABA and HA when the cells were recorded with 3 M potassium-chloride-filled electrodes. Application of GABA to voltage-clamped neurons under these circumstances resulted in an outward current that reversed at potentials varying from -72 mV to -49 mV, indicating that a variable positive shift in ECl had occurred. In these conditions, application of HA to the same neurons also resulted in an outward current that reversed at potentials from -72 mV to -48 mV. A linear regression analysis of the reversal potentials of GABA versus HA showed a correlation coefficient of 0.96 (P < 0.001). Each point represents a different PGN cell. (F and G) The inhibitory response to HA is not antagonized by block of the GABAA ionophore with the bath application of picrotoxin (20 μM).

To test this hypothesis further, neurons were impaled with electrodes containing 3 M potassium chloride, tetrodotoxin (10 μM in micropipette) was locally applied to block action potential generation, and Cl- was iontophoresed intracellularly by passing negative current (0.25-0.5 nA) through the electrode for several minutes before drug administration. If the change in membrane conductance induced by HA primarily relies on Cl-, then changing the intracellular Cl- concentration ([Cl-]i) should affect the equilibrium potential of the HA-induced response. Indeed, local application of GABA (1 mM in micropipette) to voltage-clamped neurons under such circumstances resulted in an evoked current that reversed at potentials varying from -72 mV to -49 mV (mean = -57 ± 7.2 mV; n = 7), indicating that a variable positive shift in ECl had occurred. In these conditions, application of HA also resulted in an inward current that reversed at potentials from -72 mV to -48 mV (mean = -57 ± 7.8 mV; n = 7). A linear regression analysis of the reversal potentials of GABA versus HA showed a correlation coefficient of 0.96 (P < 0.001; Fig. 2E). These results confirm that the membrane conductance activated by HA is predominantly for Cl- ions.

Next, we investigated the possibility that the conductance change elicited by HA is mediated by the same Cl- channels that underlie GABAA receptor-mediated responses. Block of the GABAA ionophore with picrotoxin (20 μM in bath) completely abolished the hyperpolarizing response to local application of the GABAA agonist muscimol (100 μM in micropipette; not shown) but failed to block the hyperpolarizing response to HA (Fig. 2 F and G; n = 4).

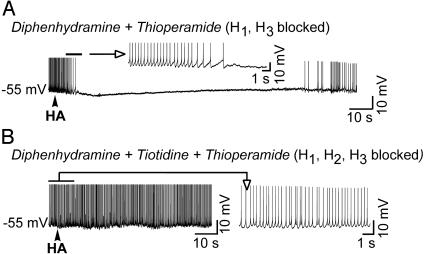

Four types of HA receptors have been distinguished in mammals: H1, H2, H3, and H4 (2, 3, 21, 22). Previous studies in lobster olfactory receptor neurons have demonstrated that HA activates a ligand-gated chloride channel through the activation of the H2 receptor (10). Application of HA to extracellularly recorded PGN neurons revealed that bath application of the H1 antagonist diphenhydramine (10 μM; n = 5) did not block the inhibitory response, but bath application of the H2 antagonist cimetidine (10 μM; n = 6) did (not shown). Similarly, with intracellular recordings we found that local application of HA to PGN neurons resulted in membrane hyperpolarization and an increase in apparent input conductance even in the presence of the H1 and H3 antagonists, diphenhydramine (2 μM) and thioperamide (2 μM), respectively, in the bath (n = 6; Fig. 3A; the bath also contained 2 μM prazosin, 2 μM yohimbine, 50 μM propranolol, 5 μM methylsergide, and 1 μM scopolamine). However, these inhibitory responses to HA were blocked when the H2-specific antagonist tiotidine (5-20 μM) was added to the bathing medium (n = 5; Fig. 3B). Together, these results indicate that the inhibitory response to HA in the PGN/nRt is mediated by H2 (and not H1 or H3) receptors.

Fig. 3.

The hyperpolarizing response of PGN neurons to HA is mediated by H2-histaminergic receptors. (A) application of HA to this PGN neuron in a solution containing diphenhydramine (2 μM) to block H1 receptors and thioperamide (2 μM) to block H3 receptors resulted in the typical inhibitory response. The bath also contained 2 μM prazosin, 2 μM yohimbine, 50 μM propranolol, 5 μM methylsergide, and 1 μM scopolamine to ensure that stimulating the receptors of other modulatory systems did not mediate this effect of HA. (B) Bath application of the H2 antagonist tiotidine (20 μM) in the presence of diphenhydramine and thioperamide blocks the hyperpolarizing response to HA (same cell as in A).

Recordings obtained with intracellular or simultaneous intracellular and extracellular multiunit electrodes placed within 50 μm of each other in the PGN revealed the generation of synchronous spindle waves that occurred either spontaneously (Fig. 4 A-C) or in response to the local application of glutamate (50 μM) in the A-laminae of the LGNd (Fig. 4D). Local application of HA (n = 8; Fig. 4A) to the surface of the slice within 50 μm of the entry point of the recording electrodes in the PGN resulted in a hyperpolarization, an increase in membrane conductance, decreased burst firing of PGN neurons to excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) barrages and hyperpolarizing current pulses, and a weakening or abolition of spindle-wave generation (Fig. 4 A and E). The application of HA to the PGN did not inhibit the EPSPs evoked in the PGN neuron by local application of glutamate in the LGNd (Fig. 4F Overlay) but did inhibit the generation of spindle waves that typically followed this brief activation of the LGNd (Fig. 4E). These results indicate that activation of histaminergic receptors in PGN neurons results in a potent block of spindle-wave generation, presumably through an increase in Cl- conductance.

The slow onset and prolonged duration of the response to local application of HA suggests that it is mediated by a second messenger system. Indeed, application of HA to neurons recorded in the whole-cell configuration, which dialyzes the internal contents of the cell with those in the patch pipette, resulted in no detectable membrane response (n = 8; not shown). To test the possibility that the inhibitory effect of HA may be due to activation of the cAMP second messenger system, we examined the effects of the adenylyl cyclase activator, forskolin (500 μM in micropipette) or a combination of forskolin and the phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxantine (100 μM in micropipette). Application of these agents to the PGN did not have any discernible effects on membrane potential, input resistance, tonic firing pattern, or spindle-wave generation in PGN neurons (n = 5; recorded with sharp electrodes in interface chamber). In contrast to the PGN, local application of forskolin (500 μM in micropipette) to the surface of the slice near the entry point of the intracellular electrode in the LGNd resulted in a slow 1- to 3-mV depolarization, a marked diminution of spindle-wave-associated inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), and an increase in membrane conductance in thalamocortical neurons (n = 5), as reported (23). These results tentatively suggest that the histaminergic receptor-mediated increases in membrane Cl- conductance in PGN neurons may be mediated through an intracellular signaling pathway distinct from the cAMP system.

Discussion

Extracellular iontophoretic application of HA in the thalamus, cerebral cortex, and hippocampus typically inhibits firing (24-26). However, intracellular investigations of responses to HA in these regions usually reveal excitatory modulatory responses that include a decrease in leak K+ conductance through H1 receptors (3), a decrease in Ca2+-activated K+ conductance (3, 8), and an enhancement of Ih through H2 receptors (4). Our present study indicates that the GABAergic neurons of the PGN, which receive histaminergic innervation (15), possess histaminergic receptors that, when activated, cause a slow and functionally potent inhibition through an increase in membrane chloride conductance. This histaminergic inhibition contrasts with that of acetylcholine, which inhibits PGN/nRt activity through increases in K+ conductance (27, 28).

The currently known actions of HA are mediated by four distinct receptor subtypes, termed H1, H2, H3, and H4 (29-32). H1, H2, and H3 receptors are all expressed in the rat nRt (33-35). HA H1 receptors are coupled to the phosphatidylinositol system and their activation is often associated with depolarizing, excitatory responses. For example, HA excites cat and guinea pig thalamocortical neurons by means of H1-receptor-mediated inhibition of a “leak” K+ current, IKL. Activation of H2 receptors also depolarizes thalamocortical neurons through an enhancement of Ih, a response that is presumably mediated by the ability of this receptor to stimulate adenylyl cyclase (4). In various invertebrate systems, the stimulation of H2 receptors can activate a ligand-gated Cl- channel (10-13). Lastly, presynaptic H3 receptors can cause inhibition of transmitter release and synthesis (22, 36), perhaps through a reduction of Ca2+ currents (6).

The histaminergic action described in the present study appears to be mediated by H2 receptors and brings the membrane potential toward the reversal potential of -73 mV through an increase in Cl- conductance. In mammals, only GABA and glycine have been consistently shown to activate Cl- conductances in neurons (7, 9). Both of these neurotransmitters activate rapid (millisecond to tens of milliseconds) inhibitory postsynaptic potentials through direct binding to a receptor site on the channel. In contrast, the Cl- conductance activated here was slow (seconds) to peak and long-lasting (up to a minute or longer), indicating that it may be mediated by the activation of a second messenger system. It has been proposed that HA may mediate fast IPSPs in supraoptic neurons, because the application of the H2-receptor antagonists cimetidine and famotidine reduced picrotoxin-sensitive, fast synaptically evoked IPSPs in these cells (37). However, such rapid hyperpolarizing responses were not demonstrated by direct application of HA, suggesting that the effects of the histaminergic antagonists may have been nonspecific, blocking IPSPs mediated by another neurotransmitter. Our present study, in contrast, shows that HA itself can inhibit neuronal activity through an increase in Cl- conductance in PGN neurons (e.g., Figs. 1 and 2). Thus, our results add a third neurotransmitter (besides GABA and glycine) to those that may control neuronal excitability through increases in Cl- conductance in the mammalian brain.

The identity of the Cl- conductance activated by HA is unknown. A large variety of Cl- channels exist in mammals, and their distribution and function in the nervous system is only partially known. In addition to ligand-gated Cl- channels, Cl- channels are also activated by increases in cAMP levels and others are sensitive to increases in [Ca2+]i. However, cAMP-activated Cl- channels, prevalent in various epithelia (9), have not yet been demonstrated in the brain (and the present results suggest that cAMP does not play a major role in mediating the effects of HA seen here). Ca2+-activated Cl- channels have been demonstrated in the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system (38, 39), but the prolonged time course of the hyperpolarizing response studied here makes it unlikely to be due to increases in [Ca2+]i. In addition, repetitive generation of Ca2+ spikes in PGN neurons results in the generation of a slow depolarization, not hyperpolarization, of the membrane potential (19, 40).

The hypothalamic histaminergic system innervates much of the nervous system and has been strongly implicated in the control of sleep and arousal (2). Clinically, a role for HA in arousal is evidenced by the sedative effects of histaminergic antagonists (41). Mice rendered genetically deficient of HA show a deficit in waking, attention, and interest in a new environment (42). Impairment of the central histaminergic system results in hypersomnia (43, 44) with increased rapid-eye movement (REM) and deep slow-wave sleep (45). The discharge of histaminergic neurons changes in relation to the sleep-wake cycle. In anticipation of the transition to the waking state, tuberomammillary neurons increase their slow, steady discharge rate (46, 47). Like the noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons that make up parallel ascending arousal systems, histaminergic neurons almost completely stop firing during REM sleep. Similarly, the release of HA in the brain is highest during waking, lower during non-REM sleep, and lowest during REM sleep (48, 49). Inactivation of the region of the histaminergic neurons through GABAergic agonists decreases arousal and promotes sleep (50).

We hypothesize that the increased release of HA associated with arousal results in an abolition of sleep-related thalamocortical activity (e.g., sleep spindles) and the promotion of the waking state through multiple actions that include depolarization of thalamocortical cells (4) and increases in membrane Cl- conductance in nRt/PGN neurons. Increases in Cl- conductance in nRt/PGN GABAergic neurons will result in inhibition of tonic, single-spike activity through hyperpolarization away from the single-spike-firing threshold and inhibition of burst firing through both hyperpolarization (or depolarization if the membrane potential is below ≈ -73 mV) and increases in membrane conductance. Increases in membrane conductance may be a particularly potent mechanism by which HA inhibits the probability of burst firing in these cells, because the low-threshold Ca2+ current generating these bursts is largely dendritic (51) and therefore susceptible to relatively small changes in conductance. Through both the depolarization of thalamocortical cells, and the slow increases in Cl- conductance in nRt/PGN neurons presented here, the ascending histaminergic system may exert a powerful influence over thalamocortical activities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (D.A.M.), the Human Frontiers Science Program (D.A.M.), the Wenner-Gren Foundation, and the Fulbright Commission (C.B.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: HA, histamine; PGN, perigeniculate nucleus; nRt, thalamic reticular nucleus; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; LGNd, dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus; IPSP, inhibitory postsynaptic potential; EPSP, excitatory postsynaptic potential.

References

- 1.Panula, P., Pirvola, U., Auvinen, S. & Airaksinen, M. S. (1989) Neuroscience 28, 585-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas, H. & Panula, P. (2003) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 121-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, R. E., Stevens, D. R. & Haas, H. L. (2001) Prog. Neurobiol. 63, 637-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormick, D. A. & Williamson, A. (1991) J. Neurosci. 11, 3188-3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sittig, N. & Davidowa, H. (2001) Behav. Brain Res. 124, 137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeshita, Y., Watanabe, T., Sakata, T., Munakata, M., Ishibashi, H. & Akaike, N. (1998) Neuroscience 87, 797-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicoll, R. A., Malenka, R. C. & Kauer, J. A. (1990) Physiol. Rev. 70, 513-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormick, D. A. (1992) Prog. Neurobiol. 39, 337-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilius, B. & Droogmans, G. (2003) Acta Physiol. Scand. 177, 119-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClintock, T. S. & Ache, B. W. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 8137-8141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witte, I., Kreienkamp, H. J., Gewecke, M. & Roeder, T. (2002) J. Neurochem. 83, 504-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuart, A. E. (1999) Neuron 22, 431-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashemzadeh-Gargari, H. & Freschi, J. E. (1992) J. Neurophysiol. 68, 9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steriade, M., McCormick, D. A. & Sejnowski, T. J. (1993) Science 262, 679-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson, J. R., Manning, K. A., Forestner, D. M., Counts, S. E. & Uhlrich, D. J. (1999) Anat. Rec. 255, 295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCormick, D. A. & Bal, T. (1997) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 185-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steriade, M., Deschenes, M., Domich, L. & Mulle, C. (1985) J. Neurophysiol. 54, 1473-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aghajanian, G. K. & Rasmussen, K. (1989) Synapse 3, 331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bal, T. & McCormick, D. A. (1992) J. Physiol. 468, 669-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCormick, D. A. & Prince, D. A. (1987) J. Physiol. 392, 147-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baudry, M., Martres, M. P. & Schwartz, J. C. (1975) Nature 253, 362-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arrang, J. M., Garbarg, M. & Schwartz, J. C. (1983) Nature 302, 832-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCormick, D. A. & Pape, H. C. (1990) J. Physiol. 431, 291-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haas, H. L. & Wolf, P. (1977) Brain Res. 122, 269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillis, J. W., Tebecis, A. K. & York, D. H. (1968) Br. J. Pharmacol. 33, 426-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sastry, B. S. & Phillis, J. W. (1976) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 38, 269-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormick, D. A. & Prince, D. A. (1986) Nature 319, 402-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu, B., Steriade, M. & Deschenes, M. (1989) Neuroscience 31, 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz, J. C., Arrang, J. M., Garbarg, M., Pollard, H. & Ruat, M. (1991) Physiol. Rev. 71, 1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vizuete, M. L., Traiffort, E., Bouthenet, M. L., Ruat, M., Souil, E., Tardivel-Lacombe, J. & Schwartz, J. C. (1997) Neuroscience 80, 321-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruat, M., Traiffort, E., Bouthenet, M. L., Souil, E., Pollard, H., Moreau, J., Schwartz, J. C., Martinez-Mir, I., Palacios, J. M., Hirschfeld, J., et al. (1991) Agents Actions 33, Suppl., 123-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bouthenet, M. L., Ruat, M., Sales, N., Garbarg, M. & Schwartz, J. C. (1988) Neuroscience 26, 553-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lintunen, M., Sallmen, T., Karlstedt, K., Fukui, H., Eriksson, K. S. & Panula, P. (1998) Eur. J. Neurosci. 10, 2287-2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlstedt, K., Senkas, A., Ahman, M. & Panula, P. (2001) Neuroscience 102, 201-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pillot, C., Heron, A., Cochois, V., Tardivel-Lacombe, J., Ligneau, X., Schwartz, J. C. & Arrang, J. M. (2002) Neuroscience 114, 173-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arrang, J. M., Garbarg, M. & Schwartz, J. C. (1987) Neuroscience 23, 149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatton, G. I. & Yang, Q. Z. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 2974-2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott, R. H., Sutton, K. G., Griffin, A., Stapleton, S. R. & Currie, K. P. (1995) Pharmacol. Ther. 66, 535-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frings, S., Hackos, D. H., Dzeja, C., Ohyama, T., Hagen, V., Kaupp, U. B. & Korenbrot, J. I. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 315, 797-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim, U. & McCormick, D. A. (1998) J. Neurophysiol. 80, 1222-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monti, J. M. (1993) Life Sci. 53, 1331-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parmentier, R., Ohtsu, H., Djebbara-Hannas, Z., Valatx, J. L., Watanabe, T. & Lin, J. S. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 7695-7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davison, C. & Demuth, E. L. (1946) Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 55, 111-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ranson, S. W. (1939) Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 41, 1-23. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiyono, S., Seo, M. L., Shibagaki, M., Watanabe, T., Maeyama, K. & Wada, H. (1985) Physiol. Behav. 34, 615-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanni-Mercier, G., Sakai, K. & Jouvet, M. (1984) C. R. Acad. Sci. Ser. III 298, 195-200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reiner, P. B. & McGeer, E. G. (1987) Neurosci. Lett. 73, 43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mochizuki, T., Yamatodani, A., Okakura, K., Horii, A., Inagaki, N. & Wada, H. (1992) Physiol. Behav. 51, 391-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strecker, R. E., Nalwalk, J., Dauphin, L. J., Thakkar, M. M., Chen, Y., Ramesh, V., Hough, L. B. & McCarley, R. W. (2002) Neuroscience 113, 663-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin, J. S., Sakai, K., Vanni-Mercier, G. & Jouvet, M. (1989) Brain Res. 479, 225-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Destexhe, A., Contreras, D., Steriade, M., Sejnowski, T. J. & Huguenard, J. R. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 169-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]