Abstract

Neurolymphomatosis is a rare manifestation of malignant lymphoma. A 74-year-old man, in complete remission from diffuse large B cell lymphoma, presented with a loss of pain and temperature sensation in the left hemiface and left upper extremity, and motor weakness in the left upper and both lower extremities. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were negative. Combined fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) revealed multiple linear hypermetabolic lesions along the mandibular branch of the left trigeminal nerve, left brachial plexus, right axillary nerve, right suprarenal plexus, right adrenal gland, right femoral nerve, and both sciatic nerves, which corresponded to the patient’s complex neurologic symptoms. C-spine and pelvic MRI revealed diffuse thickening with enhancement in the left brachial plexus and in the proximal portion of the left sciatic nerve, but negative findings for other sites identified by FDG-PET/CT. These findings suggest that FDG-PET/CT can detect peripheral nerve infiltration by malignant lymphoma earlier than MRI. Thus, if a patient with a history of lymphoma presents with neurologic symptoms, FDG-PET/CT should be performed to evaluate neurolymphomatosis.

Keywords: Neurolymphomatosis, FDG-PET/CT, Lymphoma

Introduction

Neurolymphomatosis (NL) is a rare clinical entity characterized by the infiltration of peripheral nerves, nerve roots, plexuses, or cranial nerves by malignant lymphocytes [1]. The typical manifestations of NL are progressive sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy, plexopathy, or cranial neuropathy. The diagnosis of NL is very difficult because these symptoms are also manifested by other diseases, such as mononeuropathy, polyradiculopathies, cauda equina syndrome, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuroradiculopathy [2]. The classic “gold standard” used to confirm NL is a nerve biopsy, but recent imaging modality developments have improved resolutions to the extent that affected neural structures can be detected. Combined fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) is being increasingly used for the diagnosis and staging of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [3], and it also appears to be a highly sensitive diagnostic method for facilitating the identification of NL [1]. Here, we describe a patient in complete remission from malignant lymphoma who showed via FDG-PET/CT newly found linear hypermetabolic lesions along multiple peripheral nerves and plexuses, suggestive of NL.

Case Report

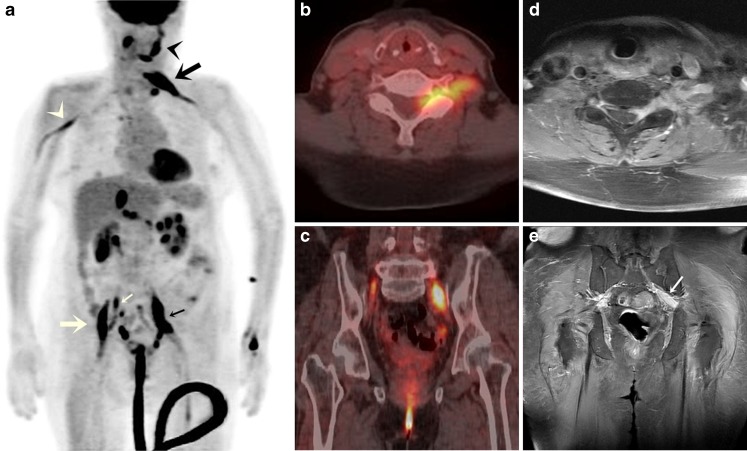

A 74-year-old man was admitted complaining of loss of pain and temperature sensation in the left hemiface and left upper extremity, and motor weakness in the left upper and both lower extremities. Six months previously, he had been diagnosed to have diffuse large B cell lymphoma. After six cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), a FDG-PET/CT scan revealed no residual tumor. However, 2 months after achieving complete remission, he developed multiple neurologic symptoms. Laboratory findings at admission showed an elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level of 809.5 U/l, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a white blood cell count of 288 with 90% lymphocytes. Cryptococcal antigen test, acid-fast staining, and culture findings were negative, and no atypical cells were noted by CSF analysis. Furthermore, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were also negative. However, FDG-PET/CT revealed multiple linear hypermetabolic lesions along the mandibular branch of the left trigeminal nerve [maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) 9.0], left brachial plexus at the C6-7 level (SUVmax 11.7), right axillary nerve (SUVmax 4.9), right suprarenal plexus (SUVmax 6.0), right adrenal gland (SUVmax 12.8), right femoral nerve (SUVmax 12.1), and both sciatic nerves (SUVmax 13.0), which corresponded with the patient’s complex neurologic symptoms (Fig. 1a, b, c). In addition, FDG-PET/CT revealed hypermetabolic lesions in the right cervical and left supraclavicular lymph nodes. These findings suggested lymphoma recurrence and NL. Pelvic and C-spine MRI revealed diffuse thickening with enhancement in the left brachial plexus and in the proximal portion of the left sciatic nerve on gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images (Fig. 1d, e), but negative findings at other sites identified by FDG-PET/CT. Although a nerve biopsy was not performed, recurrence of malignant lymphoma and NL were diagnosed. Treatment with intravenous high-dose methotrexate was initiated, but the patient expired 8 days later due to the development of neutropenia and rapidly progressive pneumonia.

Fig. 1.

a Maximum intensity projection FDG-PET/CT image showing linear hypermetabolic lesions involving multiple peripheral nerves, corresponding to the patient’s complex neurologic symptoms, as follows. Involvement of the mandibular branch of the left trigeminal nerve (black arrowhead) corresponded to loss of pain and temperature sensation in the left hemiface. Left brachial plexus involvement (black large arrow) corresponded to loss of pain and temperature sensation and motor weakness in the left upper extremity. Left sciatic nerve involvement (small black arrow) corresponded to motor weakness of the left lower extremity. Right sciatic nerve (small white arrow) and right femoral nerve (large white arrow) involvement corresponded to motor weakness of right lower extremity. However, the right axillary nerve (white arrowhead) lesion did not cause any symptom. b FDG-PET/CT showed a linear hypermetabolic lesion in the left brachial plexus. c FDG-PET/CT showed linear hypermetabolic lesions in both sciatic nerves. d Cervical spine T1 weighted MRI showing diffuse thickening with gadolinium enhancement of the left brachial plexus. e Pelvis MRI showing diffuse thickening with enhancement in the proximal portion of the left sciatic nerve

Discussion

NL is a rare but well-described entity, in which malignant lymphocytes infiltrate the peripheral nervous system (PNS) [4]. Although NL would appear to be the least common neurologic manifestation of lymphoma, Baehring et al. [2] estimated that NL represents 10% of primary lymphomas of the nervous system (0.2% of all NHLs). Furthermore, between 8.5 and 29% of NHLs metastasize to the nervous system, and an estimated 10% of these involve the PNS [2].

No optimal diagnostic tools are available to detect NL, and we originally overlooked NL, because its clinical manifestations are similar to those of other non-neoplastic neuropathies. The classic “gold standard” for diagnosing NL is a nerve biopsy, but nerve biopsies have their limitations, such as difficulties associated with accessing target nerves and neurological sequelae. However, recent studies have shown promising results for state of the art imaging modalities. Grisariu et al. [1] retrospectively analyzed 50 patients of NL, and found that MRI and FDG-PET/CT was positive in 77 and 84%, respectively. CSF cytology was positive in 40%, and a nerve biopsy was positive in 88% [1]. The use of FDG-PET during the primary staging of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and NHL showed that PET adds to the sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy of determining gross disease extent [5]. Furthermore, an early FDG-PET assessment of response to chemotherapy is becoming a routine part of management in HL and histologically aggressive NHL. Although the total number of reported NL cases diagnosed by FDG-PET/CT is still small, positive findings are highly suggestive of a diagnosis of NL, particularly in patients with a known history of hematologic malignancy [1, 6]. Furthermore, FDG-PET/CT can often diagnose NL when other diagnostic modalities have failed [7], and can allow disease extent to be visualized and therapeutic response to be determined [8].

In our case, the complex neurologic symptoms were difficult to understand before FDG-PET/CT scanning. Pelvic and C-spine MRI showed diffuse thickening and contrast enhancement in the left brachial plexus and left sciatic nerve, but these findings could not explain other symptoms, such as loss of pain and temperature sensation in the left hemiface or motor weakness in the right lower extremity. On the other hand, FDG-PET/CT revealed multiple linear hypermetabolic lesions in the mandibular branch of the left trigeminal nerve and in the right sciatic nerve, which were not detected by MRI. FDG-PET/CT also revealed a hypermetabolic asymptomatic lesion along the right axillary nerve. Interestingly, the right axillary nerve had a lower SUVmax value than the symptomatic nerves (SUVmax 4.9 vs >9.0), which suggest that FDG-PET/CT can detect subclinical lesions and early infiltration into peripheral nerves not detectable by MRI. Thus, we found FDG-PET/CT extremely helpful in terms of understanding our patient’s neurologic symptoms and making an early diagnosis without having to adopt an invasive approach.

Summarizing, we found that FDG-PET/CT detected peripheral nerve infiltration by malignant lymphoma earlier than MRI, and thus, we recommend that if a patient with a history of lymphoma presents with neurologic symptoms, FDG-PET/CT should be performed to evaluate the possibility of NL.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Nuclear Research & Development Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science & Technology (MEST) (grant code: 2010-0017515).

References

- 1.Grisariu S, Avni B, Batchelor TT, van den Bent MJ, Bokstein F, Schiff D, et al. Neurolymphomatosis: an International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group report. Blood. 2010;115(24):5005–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baehring JM, Damek D, Martin EC, Betensky RA, Hochberg FH. Neurolymphomatosis. Neuro Oncol. 2003;5(2):104–15. doi: 10.1215/S1522-8517-02-00017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiepers C, Filmont JE, Czernin J. PET for staging of Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(Suppl 1):S82–8. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khong P, Pitham T, Owler B. Isolated neurolymphomatosis of the cauda equina and filum terminale: case report. Spine. 2008;33(21):E807–11. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818441be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanter P, Zeidman A, Streifler J, Marmelstein V, Even-Sapir E, Metser U, et al. PET-CT imaging of combined brachial and lumbosacral neurolymphomatosis. Eur J Haematol. 2005;74(1):66–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munker R, Glass J, Griffeth LK, Sattar T, Zamani R, Heldmann M, et al. Contribution of PET imaging to the initial staging and prognosis of patients with Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1699–704. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gan HK, Azad A, Cher L, Mitchell PL. Neurolymphomatosis: Diagnosis, management, and outcomes in patients treated with rituximab. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12(2):212–5. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strobel K, Fischer K, Hany TF, Poryazova R, Jung HH. Sciatic nerve neurolymphomatosis—extent and therapy response assessment with PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32(8):646–8. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3180a1ac74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]