Abstract

In human tumors, and in mouse models, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) levels are frequently correlated with tumor development/burden. In addition to intrinsic tumor cell expression, COX-2 is often present in fibroblasts, myofibroblasts and endothelial cells of the tumor microenvironment, and in infiltrating immune cells. Intrinsic cancer cell COX-2 expression is postulated as only one of many sources for prostanoids required for tumor promotion/progression. Although both COX-2 inhibition and global Cox-2 gene deletion ameliorate ultraviolet B (UVB)-induced SKH-1 mouse skin tumorigenesis, neither manipulation can elucidate the cell type(s) in which COX-2 expression is required for tumorigenesis; both eliminate COX-2 activity in all cells. To address this question, we created Cox-2 flox/flox mice, in which the Cox-2 gene can be eliminated in a cell-type-specific fashion by targeted Cre recombinase expression. Cox-2 deletion in skin epithelial cells of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice resulted, following UVB irradiation, in reduced skin hyperplasia and increased apoptosis. Targeted epithelial cell Cox-2 deletion also resulted in reduced tumor incidence, frequency, size and proliferation rate, altered tumor cell differentiation and reduced tumor vascularization. Moreover, Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + papillomas did not progress to squamous cell carcinomas. In contrast, Cox-2 deletion in SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox; LysMCre + myeloid cells had no effect on UVB tumor induction. We conclude that (i) intrinsic epithelial COX-2 activity plays a major role in UVB-induced skin cancer, (ii) macrophage/myeloid COX-2 plays no role in UVB-induced skin cancer and (iii) either there may be another COX-2-dependent prostanoid source(s) that drives UVB skin tumor induction or there may exist a COX-2-independent pathway(s) to UVB-induced skin cancer.

Introduction

Ultraviolet (UV) irradiation from solar exposure is the major etiologic/environmental factor leading to clinically important cutaneous squamous cell tumors and basal cell tumors. UV irradiation causes acute inflammation, with consequent epidermal hyperplasia. Repeated UVB irradiation of SKH-1 hairless mice is among the most well-studied experimental skin cancer induction models (1). In SKH-1 mice, UVB irradiation elicits acute inflammation resembling those that observed in the skin of humans exposed to high environmental UV radiation levels. Moreover, chronic UVB irradiation of SKH-1 mice elicits premalignant and malignant skin tumors similar to those observed in patients exposed chronically to excessive environmental UV radiation.

Prostaglandins play a major role in modulating the inflammatory properties observed in UVB-irradiated skin and in UVB-induced experimental tumors (2). Two cyclooxygenase isoforms, COX-1 and COX-2, are responsible for production of prostaglandin H2 (PGH2), the common precursor to a wide range of prostanoids (3). COX-1 is expressed constitutively in most tissues; in contrast, COX-2 is highly inducible in many tissues, in response to many stimuli (4). In mouse skin, UVB irradiation induces extensive Cox-2 gene activation and COX-2 protein accumulation (5,6). Both COX-1 and COX-2 are present in non-melanoma skin cancers from patients and in UVB radiation-induced SKH-1 mouse premalignant skin papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) (2). COX-dependent prostaglandins are, consequently, postulated to be drivers of UVB-induced skin cancer promotion and progression (7).

Both coxibs (COX-2-selective inhibitors) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2 are widely used to investigate the roles of the cyclooxygenases in animal cancer models. A recent population-based study suggested that NSAIDs may decrease human SCC risk (8). Both indomethacin (an NSAID) and celecoxib (a COX-2 selective inhibitor), delay appearance of UVB-induced skin tumors on SKH-1 mice. Moreover, celecoxib reduced UVB-induced tumor formation by ~80%, suggesting that global COX-2 inhibition in mice can nearly completely prevent UVB skin tumor induction (9). COX-2-specific inhibition suggests that COX-2-derived prostanoids play a major role in UVB-induced skin tumor promotion and progression.

A second approach to determine the roles of COX-1 and COX-2 in biological phenomena has been the use of mice with global Cox-1 and Cox-2 gene deletions (2). The use of these genetically altered mice eliminates questions of off-target NSAID and coxib effects but introduces potential problems of altered developmental and physiological mechanisms in the mutant mice to compensate for absence of the COX enzymes. Nevertheless, Cox-1 − /− and Cox-2 − /− mice have been used to investigate COX-1 and COX-2 roles in animal models of neuroinflammation, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, infertility, colitis and many cancers (10).

COX-1 and COX-2 roles in UVB-induced skin cancer have been investigated using SKH-1 mice with global Cox-1 and Cox-2 gene deletions. Deleting both copies of the Cox-1 gene in SKH-1 mice had no effect on UV-induced skin tumor number, average tumor size or time of tumor onset (11). However, SKH-1 Cox-2 − /− mice could not be used in similar studies; although viable, SKH-1 Cox-2 − /− mice could not withstand the UVB carcinogenesis paradigm. Heterozygous SKH-1 Cox-2 +/− mice, however, demonstrated reduced tumor incidence and multiplicity in response to UVB irradiation, suggesting a Cox-2 gene dosage effect in this tumor induction protocol (12). As a consequence, in the absence of studies with global SKH-1 Cox-2 − /− deletion, the extent of the requirement for COX-2 expression could not be determined.

A requisite role for epithelial cell-intrinsic (e.g. tumor cell autonomous) COX-2 expression versus requisite role(s) for COX-2 expression in the various cells of the microenvironment (e.g. fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, endothelial cells, infiltrating myeloid cells) in driving tumor proliferation and progression are subjects of substantial speculation and debate for many epithelial cancers (13). An et al. (5) report COX-2 expression ‘…in tumor stroma… surrounding inflammatory infiltrate, which consisted of lymphocytes and macrophages…and dermal fibroblasts’ in UVB-induced SKH-1 SCCs. Pentland et al. (14) observe ‘…greatly increased density of intensely stained cells in the dermis, which appeared to be lymphocytes and histiocytes’. Although both COX-2 pharmacologic inhibition and Cox-2 gene knockout data demonstrate a role for COX-2 in UVB-induced skin cancer in SKH-1 mice, neither of these approaches can determine in what cell type(s) COX-2 expression is required to drive UVB-induced skin cancer promotion and subsequent progression to SCC; both pharmacologic inhibition and global Cox-2 deletion eliminate COX-2-driven prostanoid production in all cells.

We developed Cox-2 flox mice (15) and used them to study COX-2 cell-specific roles in animal models of colitis (16), cardiac function (17) and pancreatic cancer progression (18). Here, we use SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox mice to determine possible roles for intrinsic skin epidermal cell-specific COX-2 expression and myeloid cell-specific COX-2 expression in UVB-induced skin tumorigenesis in SKH-1 mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

Cox-2 flox/flox mice, in which Cox-2 exons are flanked by loxP sites, were described previously (15). K14Cre (Tg(KRT14-Cre)1Amc) and LysMCre knock-in (B6.129P2-Lyz2tm1(cre)lfo/J) mice were from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME); SKH1-HR from Charles River Labs, Wilmington, MA. Cox-2 flox/+;K14Cre + and Cox-2 flox/+ ;LysMCre + mice were backcrossed onto SKH-1 mice for at least five generations. The resulting SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice and their littermate SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox mice, and the SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox; LysMCre + mice and their littermate SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox mice, were used for UVB irradiation experiments. Animal experiments were performed following approval by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

UV irradiation

The UV apparatus consisted of eight Westinghouse FS20 sunlamps, an IL-1400 radiometer, and an attached UVB photometer. Spectral irradiance for the UV lamps was 280–400nm, 80% in the UVB region and 20% in the UVA region. Peak light source intensity was 297nm; fluence 60cm from the mouse dorsal surface was 0.48–0.50 mJ/cm2/s. Mice were placed in individual compartments in a plastic holder on a rotating base to abrogate fluence differences across the UV sources. For tumor studies, Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice (n = 25), their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (n = 30), Cox-2 flox/flox;LysMCre + mice (n = 31) mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (n = 37) were UV irradiated three times weekly with an initial dose of 90 mJ/cm2 for the first week, followed by a weekly 10% increase until a dose of 175 mJ/cm2 was reached. Weekly tumor counts were performed after the appearance of the first tumor and continued until the termination of the experiment. At termination of the experiment, tumor diameters were measured and tumors were assigned to size categories. Tumors were processed for histological analysis. Differences in tumor multiplicity and incidence were analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U-test and the χ2 test, respectively.

Epidermal thickness

Epidermal thickness was measured on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections, using a ×20 objective. Epidermal thickness was defined as the distance between the basement lamina and the apical surface of the uppermost nucleated keratinocytes (19). Measurements (20 fields per mouse, 4 mice per genotype) and quantification were done using NIS-Elements BR 3.00 software (Nikon).

Immunohistochemistry reagents and procedures

Mouse skin and papillomas fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were paraffin-embedded and sectioned (4 μm thickness). Sections were stained with H&E or processed for immunohistochemical analysis. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides at 95oC in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) or Tris Buffer (pH 9.0) for 15 min or by treating slides at 37°C in Proteinase K solution (DAKO, Carpentaria, CA) prior to staining. Primary antibodies were COX-2 (160106) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), F4/80 (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC), K1 (Covance, Princeton, NJ), Ki67 (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), γH2AX (#9718, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) (#9661, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), p53 (NCL-p53-CM5p, Novocastra) and CD31 (ab28364, abcam, Cambridge, MA). Samples were visualized using a NIKON Eclipse TE 2000-U microscope.

Quantification of immunohistochemical staining

Skin.

Skin proliferation indices were calculated as the percentage of Ki67-positive staining basal cells. The percentage of K1-positive basal cells is presented as the number of K1-positive basal cells/total basal keratinocytes. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as number of cleaved-Caspase-3-positive cells (apoptotic cells)/total epidermal cells. Ki67-positive cells, K1-positive basal cells and apoptotic cells were each determined on at least four random areas for each section, three sections per mouse and three mice per genotype. For COX-2, p53 and γH2AX quantification, slides were digitized on a ScanScope AT (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA) instrument and morphometric analysis was performed using Definiens’ Tissue Studio (Definiens, Parsippany, NJ) software. Using the predefined nuclear detection module and classification tool to determine the percentage of p53 or γH2AX-positive cells, positive and negative nuclei within each interfollicular epithelial region were identified. Using the predefined cytoplasm detection module and classification tool to determine the percentage of COX-2-positive cells, positive and negative stained cells within each epithelial region were identified. Thresholds were set to classify hematoxylin stain for negative nuclei and diaminobenzidine stain for positive nuclei.

Tumor.

For tumor sections, slides were digitized on the ScanScope AT instrument and morphometric analysis was performed as described above. Ki67-positive cells were determined with the predefined nuclear detection module and classification tool; positive and negative nuclei within each epithelial region were identified. K1-positive cells were identified using the predefined cytoplasm detection module and classification tool. Thresholds were set to classify hematoxylin stain for negative nuclei and diaminobenzidine stain for positive nuclei. To determine vessel density, the predefined vessel detection module and classification tool were used; numbers of positive vessels per unit area, based on CD31-positive staining, within each tumor region were identified.

All data were analyzed for statistical significance using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Scanning and scan analyses were performed with help from the Translational Pathology Core Laboratory, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Results

Targeted Cox-2 deletion in skin epidermal cells reduces UVB tumor induction

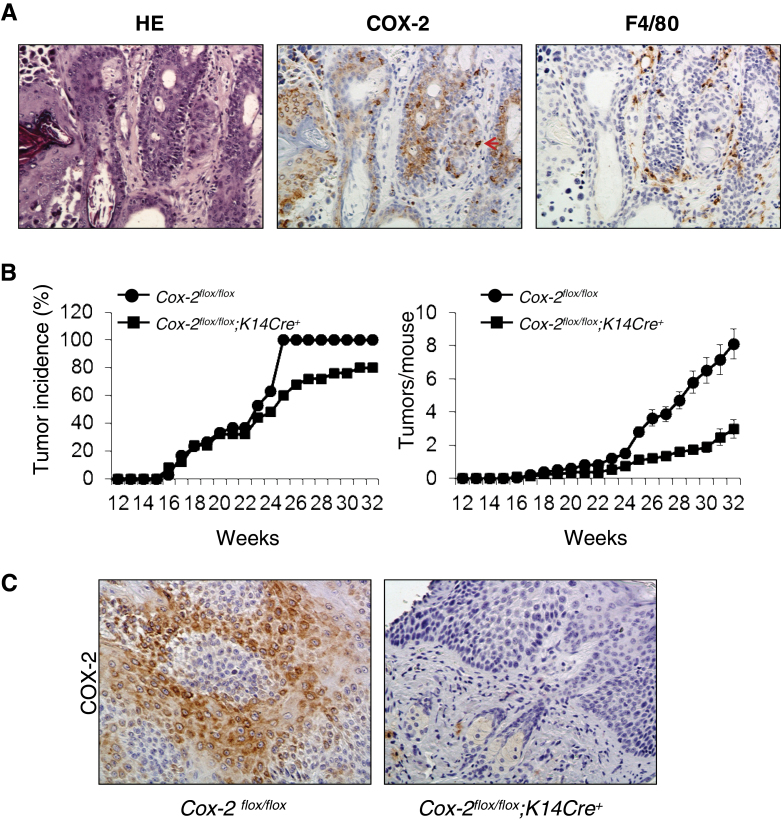

In addition to epithelial cell COX-2, expression of COX-2 in myeloid cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts and myofibroblasts has been suggested to contribute to epithelial cell tumor promotion (5–7). COX-2 is expressed extensively in epithelial cells of UVB-induced tumors from Cox-2 flox/flox mice (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1.

Epidermal cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion reduces UVB-induced mouse skin papilloma formation. (A) Consecutive sections of a UVB-induced skin papilloma of a Cox-2 flox/flox mouse were stained for H&E, COX-2 expression and F4/80 expression. The arrows indicate cells with positive F4/80 and COX-2 expression. (B) Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice (n = 25) and Cox-2 flox/flox littermates (n = 30) were subjected to UVB-irradiated skin cancer induction as described in Materials and methods. (C) Epithelial cells of papillomas from UVB-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox mice express COX-2. In contrast, epithelial cells of papillomas from UVB-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice do not express COX-2.

SKH-1 Cox-2 − /− mice with homozygous global Cox-2 gene deletions, although viable, do not survive the standard UVB irradiation tumor induction protocol (12). However, viability of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ; K14Cre + mice with homozygous epidermal cell-specific-targeted Cox-2 gene deletions is not reduced in response to the UVB tumor induction protocol. Consequently, we could determine whether epithelial cell-intrinsic COX-2 expression is required for UVB skin tumor induction.

Reduced skin tumor incidence occurred in UVB-treated Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice relative to their Cox-2 flox/flox littermate mice (Figure 1B, left panel). There was a significant delay in tumor development in Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice compared with their UVB-irradiated littermate Cox-2 flox/flox controls; 24 weeks after UV irradiation, only 60% of the Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice developed papillomas. In contrast, all Cox-2 flox/flox mice had papillomas by this time (P < 0.05, χ2 test). There was also a substantial reduction in tumor multiplicity in UVB-treated Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice compared with littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (Figure 1B, right panel). At the end of the experiment, Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice with an epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 deletion had only one-third the tumor number present on littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test).

It is possible that K14Cre-dependent Cox-2 flox/flox gene cleavage is incomplete in SKH-1 mice and consequently tumors on UVB-treated Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice might be derived from mice able to express COX-2 from an uncleaved Cox-2 allele(s). However, COX-2 protein was easily detectable in epithelial cells of tumors from control Cox-2 flox/flox mice (Figure 1C, left panel), but not in epithelial cells of tumors from Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice (Figure 1C, right panel), suggesting that intrinsic COX-2 expression in epithelial cells is not driving tumor promotion in those tumors present on Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice.

Targeted myeloid cell Cox-2 deletion has no effect on UVB skin tumor induction

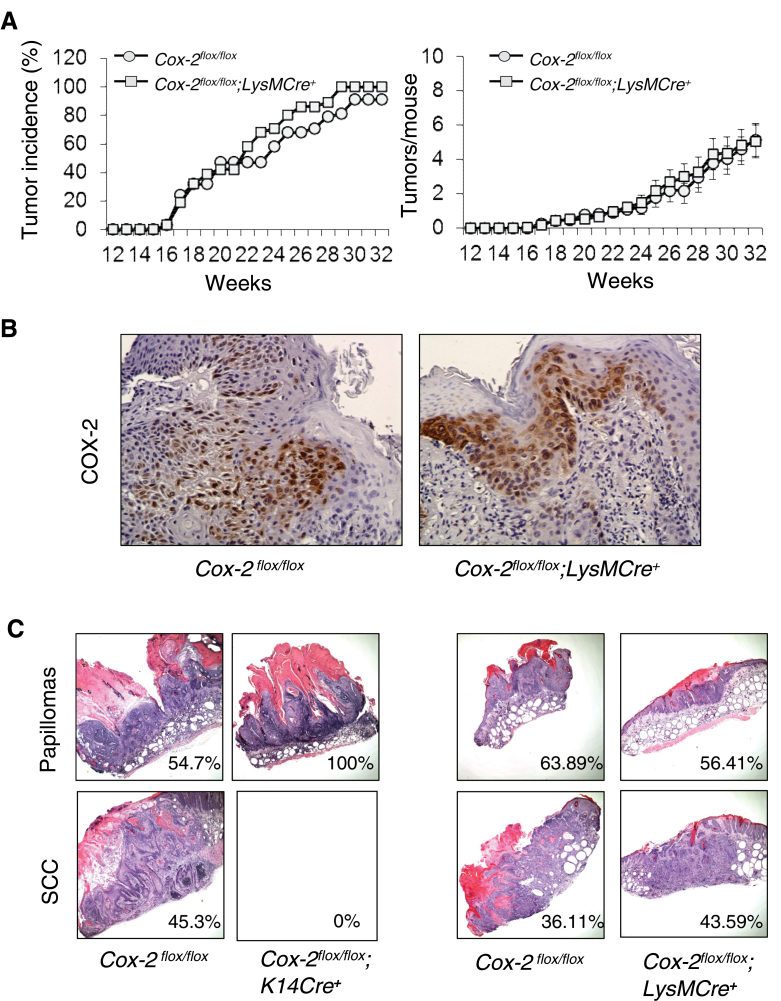

Macrophages in UVB irradiation-induced skin tumors of wild-type SKH-1 mice and SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox mice express COX-2 protein (5) (Figure 1A). In contrast to the results for mice with epidermal cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion, myeloid cell Cox-2 gene deletion had no discernible effect on UVB skin tumor induction. Both skin tumor incidence (Figure 2A, left panel; P = 0.279, χ2 test) and tumor multiplicity (Figure 2A, right panel; P = 0.44, Mann–Whitney U-test) in UVB-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox;LysMCre + mice and littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice were statistically indistinguishable. COX-2 protein expression in skin tumors from Cox-2 flox/flox;LysMCre + mice and littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (Figure 2B) is observed primarily in tumor epithelial cells.

Fig. 2.

Myeloid cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion has no effect on UVB-induced mouse skin papilloma formation. (A) UVB-irradiated skin tumor induction in Cox-2 flox/flox ;LysMCre + mice (n = 31) and Cox-2 flox/flox littermates (n = 37). (B) Epithelial cells of papillomas from UVB-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox mice and epithelial cells of papillomas from UVB-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox ;LysMCre + mice both express COX-2. (C) Representative papillomas and SCCs from Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox controls, and from Cox-2 flox/flox ;LysMCre + mice and their littermate controls. The number in each box is the percentage of papillomas (upper panels) and SCCs (lower panels) for each of the four cohorts of UVB-irradiated mice. Tumors were harvested at 32 weeks of tumor induction for histologic evaluation.

Representative tumors harvested at week 32 were evaluated histologically (Figure 2C). Many UVB-induced papillomas from Cox-2 flox/flox; LysMCre + mice, and papillomas from UVB-treated control Cox-2 flox/flox mice from the experiments with both Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice and Cox-2 flox/flox;LysMCre + mice, progressed to SCCs. In contrast, no UVB-induced papillomas from Cox-2 flox/flox;K14Cre + mice, in which the Cox-2 gene is specifically deleted in epidermal cells, progressed to SCCs. The frequency of SCCs (i.e. the percent of conversion of papillomas to carcinomas) ranged between 36 and 45% for UV-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox;LysMCre + mice, Cox-2 flox/flox littermate controls of Cox-2 flox/flox;LysMCre + mice and Cox-2 flox/flox littermate controls of Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice; in contrast, no papillomas on UV-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice progressed to SCCs (Figure 2C).

We conclude that Cox-2 gene deletion in skin epidermal cells results in substantially reduced frequency of skin tumor induction in response to UVB irradiation. Intrinsic epidermal cell Cox-2 gene deletion also retards UVB-induced papilloma progression to SCCs. In contrast, targeted Cox-2 gene deletion in myeloid cells does not modulate UVB skin tumor induction.

UVB-induced skin epidermal hyperplasia is reduced in Cox-2flox/flox; K14Cre+ mice

Global Cox-2 − /− mice in a 129Ola/C57Bl6 background exhibit significantly decreased epidermal hyperplasia following UVB treatment compared with Cox-2 +/+ littermate mice (20). Pharmacologic studies also suggest that COX-2 plays a role in UVB-induced skin hyperplasia in SKH-1 hairless mice (21). However, the cell-type-specific role of the Cox-2 gene in UVB-induced hyperplasia has not been examined in SKH-1 mice.

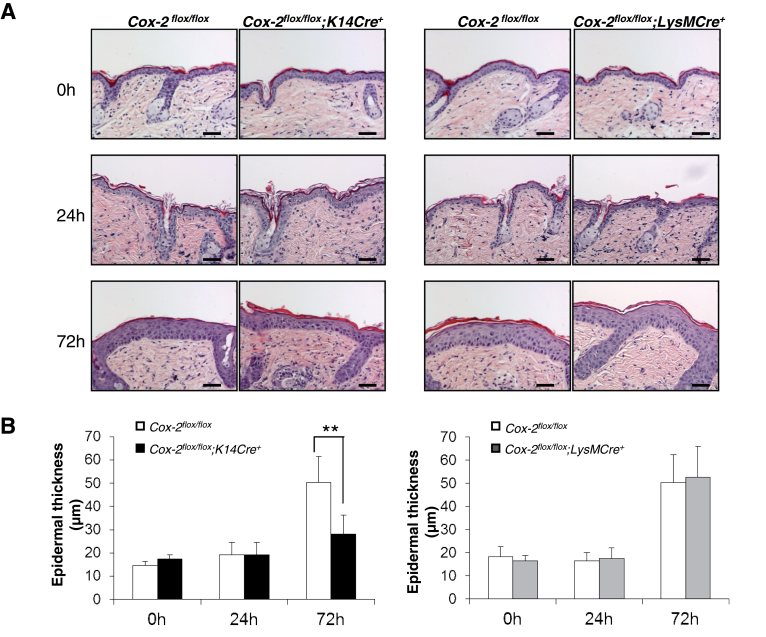

Skin morphology is similar for unirradiated SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox; K14Cre + mice, Cox-2 flox/flox;LysMCre + mice and their Cox-2 flox/flox littermates (Figure 3). To determine the effect of UVB irradiation on skin hyperplasia in SKH-1 mice, and the role of cell-specific COX-2 expression on this response, we measured epidermal thickness following UV exposure of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice, Cox-2 flox/flox ; LysMCre + mice and their respective Cox-2 flox/flox littermate controls. Substantially induced hyperplasia is evident 72 h after UVB exposure in both Cox-2 flox/flox cohorts (Figure 3). Acute UV irradiation of Cox-2 flox/flox ;LysMCre + mice, in which UVB tumor induction is not effected (Figure 2), induces skin hyperplasia similar to Cox-2 flox/flox littermate controls (Figure 3). In contrast, Cox-2 flox/flox ; K14Cre + mice, which exhibit reduced skin tumor formation in response to UVB irradiation (Figure 2), also exhibit reduced skin hyperplasia 72 h after UV irradiation compared with Cox-2 flox/flox controls (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Epidermal hyperplasia is reduced in response to UVB irradiation in mice with an epidermal cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion but is not affected in UVB-irradiated mice with a myeloid cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion. (A) H&E sections from the skin of Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice (n = 4) and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (n = 4), and from skin of Cox-2 flox/flox ;LysMCre + mice (n = 4) and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (n = 4) at the times shown following a single UVB irradiation. After UV irradiation, Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice exhibit decreased epidermal hyperplasia compared with littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice. (B) Quantification of epidermal thickness. Error bars are standard deviation. **P < 0.01. Scale bar: 50 µm.

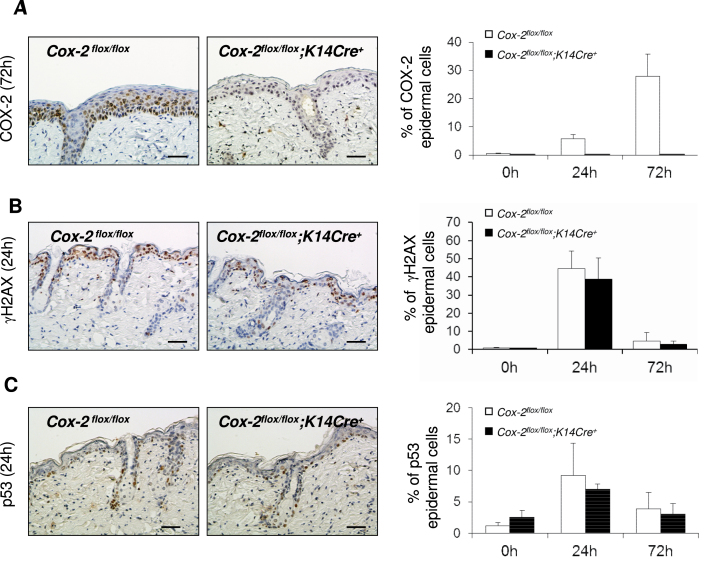

COX-2 expression is induced in skin epithelial cells of SKH-1 mice following a single UVB irradiation exposure, and is absent in mice with an epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion

COX-2 expression was easily detectable in epithelial cells of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox mice following UVB irradiation (Figure 4A). Although modest expression was observed at the first time point monitored (24 h), the percentage of cells expressing COX-2 was substantially increased at 72 h. In contrast, no COX-2 expression was detectable in skin epithelial cells of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice, again demonstrating the extensive penetrance of Cre cleavage of the Cox-2 flox/flox genes by keratin14-driven Cre recombinase.

Fig. 4.

COX-2 expression and measurements of DNA damage in SKH-1 mice with an epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion and in their littermate controls. (A) COX-2 protein expression in the interfollicular epidermis of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice (n = 3) and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (n = 3) following a single UVB irradiation. The graph on the right shows quantification of the percentage of COX-2-positive epithelial cells. The panels on the left show immunohistochemical (IHC) results for cells irradiated for 72h, the time of maximal COX-2 expression in this experiment. (B) γH2AX in the interfollicular epidermis of SKH-1Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice (n = 3) and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (n = 3) following a single UVB irradiation. The graph on the right shows quantification of the percentage of γH2AX-positive interfollicular epithelial cells. The panels on the left show IHC results for cells irradiated for 24h. (C) p53 protein expression in the interfollicular epidermis of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice (n = 3) and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (n = 3) following a single UVB irradiation. The graph on the right shows quantification of the percentage of p53-positive interfollicular epithelial cells. The panels on the left show IHC results for cells irradiated for 24h. Scale bar: 50 µm.

DNA damage measurements in skin epithelial cells of SKH-1 mice are similar, following a single UVB irradiation exposure, in SKH-1 control Cox-2flox/flox mice and Cox-2flox/flox; K14Cre+ mice with an epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion

Phosphorylation of H2AX (γH2AX) in epithelial cells, reflecting DNA damage, is an early response to SKH-1 mouse skin UVB irradiation (22,23). To determine whether intrinsic COX-2 expression in the skin epithelial cells modulates this measurement of DNA damage following UVB irradiation, we analyzed γH2AX in SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ; K14Cre + mice and in Cox-2 flox/flox littermate controls (Figure 4B). No difference in the time or extent of γH2AX was observed.

Like γH2AX, p53 is an early response to a single UVB irradiation of SKH-1 mice (22–24). Sulindac, a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, is reported to reduce p53 expression in UVB-irradiated skin of SKH-1 mice (25). UVB irradiation induced p53 expression in both SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + and their Cox-2 flox/flox littermate controls. However, there was no significant difference detectable between the two strains (Figure 4C).

Epidermal cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion in SKH-1 mice does not alter acute UVB-induced epidermal cell proliferation or epidermal cell differentiation, but increases UVB-induced apoptosis

Proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes and keratinocyte precursors are modulated by a variety of factors. During movement of basal cells to suprabasal positions, the cells undergo terminal differentiation. The balance between keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation and cell death regulates epidermal homeostasis (26). To identify possible mediators for the altered hyperplastic response to acute UVB irradiation for SKH-1 mice with an epidermal cell-specific-targeted Cox-2 gene deletion (Figure 3), we examined Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their Cox-2 flox/flox littermates for possible differences in cell proliferation, epidermal cell differentiation and apoptosis following UVB irradiation (Figure 5).

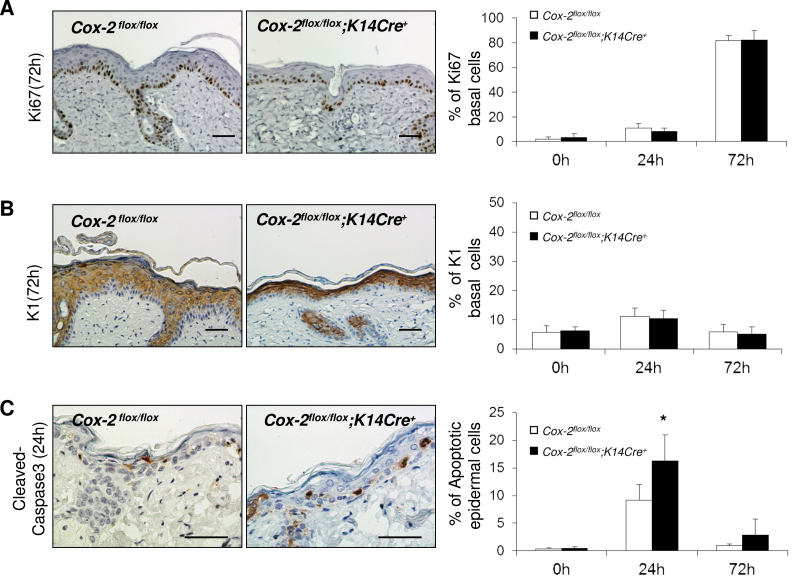

Fig. 5.

Epidermal cell-specific Cox-2 deletion does not reduce epithelial cell proliferation or increase premature basal cell differentiation in response to UVB irradiation but results in increased apoptosis. (A) Ki67 protein expression in the skin of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice following a single UVB irradiation. The graph on the right shows quantification of the percentage of Ki67-positive basal epithelial cells. The panels on the left show IHC results for cells irradiated for 72h, (B) K1 protein expression in the skin of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice following a single UVB irradiation. The graph on the right shows quantification of the percentage of K1-positive basal epithelial cells. The panels on the left show IHC results for cells irradiated for 72h, (C) cleaved Caspase-3 protein expression in the interfollicular epidermis of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice following a single UVB irradiation. The graph on the right shows quantification of the percentage of cleaved Caspase-3-positive (apoptotic cells) epithelial cells. The panels on the left show IHC results for cells irradiated for 24h. Error bars are standard deviation. *P < 0.05. Scale bar: 50 µm.

To determine if reduced skin hyperplasia of UVB-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice relative to littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (Figure 3) correlates with a reduction in keratinocyte proliferation, Ki67 expression was examined in skin samples from untreated mice and from mice at 0, 24 and 72 h after a single UVB irradiation. Untreated skin of both Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and Cox-2 flox/flox littermates have very few Ki67-positive cells. Following UVB irradiation, the skin of mice with an epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 deletion and the skin of their control mice had essentially identical, highly proliferative responses (Figure 5A, 72 h). Quantification of proliferation responses is shown in Figure 5A, right panel.

When keratinocytes become committed to differentiation, they express Keratin 1 (27). Increased basal cell differentiation was reported to contribute to the reduced hyperplasia in the skin of 7,12-dimethylbenz[α]anthracene/12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol- 13-acetate (DMBA/TPA)-treated mice with a global Cox-2 − /− deletion (28). K1 antigen staining was very low in basal cells of untreated skin from both Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox controls. A single UVB irradiation of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their Cox-2 flox/flox littermates resulted in similar (low) percentages of skin basal cells expressing the K1 keratinocyte differentiation antigen (Figure 5B, 72 h). Quantification of the data is shown in Figure 5B, right panel.

UVB radiation-induced apoptosis was significantly increased in homozygous global Cox-2 − /− 129Ola/C57Bl6 knockout mice compared with littermate Cox-2 +/+ mice (20). Although not examined in homozygous Cox-2 SKH-1 knockouts, UVB-induced apoptosis was also increased, relative to control littermate Cox-2 +/+ mice, in heterozygous SKH-1 global Cox-2 +/- mice (12). To determine if the increase in apoptosis that accompanies loss of COX-2 expression is mediated by intrinsic epithelial cell-specific COX-2 expression, we examined UVB-induced apoptosis in SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + and littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice. Skin of both unirradiated SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and control littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice has very few apoptotic cells, as indicated by cleaved Caspase-3 staining. Skin of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox mice has clearly detectable cleaved Caspase-3-positive apoptotic cells after a single acute UVB radiation exposure (Figure 5C, 24 h). Moreover, following UVB irradiation, the frequency of apoptotic cells is significantly increased at 24 h in the skin of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice with an epidermal cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion, relative to littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice. Quantification of cleaved Caspase-3-positive apoptotic cells is shown in Figure 5C, right panel. In contrast, the apoptotic index was identical in SKH-1 control Cox-2 flox/flox mice and Cox-2 flox/flox ;LysMCre + mice (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online), in which Cox-2 gene deletion has no effect on UVB skin tumor induction (Figure 2). These data suggest a possible contributing role for the absence of COX-2 expression in the increased apoptosis and reduced hyperplasia observed in UVB-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice compared with control Cox-2 flox/flox mice, and for the reduced tumor frequency observed in UVB-irradiated Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice (Figure 1).

UVB-induced tumors from mice with an epidermal cell-specific Cox-2 deletion exhibit both a decreased proliferation index and an increased extent of differentiation compared with tumors from littermate Cox-2flox/flox mice

Fewer tumors are induced in response to UVB irradiation in Cox-2 flox/flox ; K14Cre + mice with an epithelial cell-targeted Cox-2 gene deletion than in their Cox-2 flox/flox littermates (Figure 1). Moreover, the papillomas that are induced grow more slowly and do not progress to SCCs (Figure 2C). In acutely irradiated skin, there are no measurable differences either in UVB-induced epithelial cell proliferation or in basal cell differentiation (Figure 5A and B). However, UVB-induced apoptosis occurs to a greater extent in skin of Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice than in their Cox-2 flox/flox littermates (Figure 5C). Here, we measure those same properties in UVB-induced skin papillomas to assess whether these same intrinsic epithelial cell characteristics are modified by epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion in skin tumors of Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice relative to tumors on control Cox-2 flox/flox mice.

Although proliferation rates for skin epithelial cells of UVB-treated Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their UVB-irradiated littermate control Cox-2 flox/flox mice were similar (Figure 5A), proliferation rates for epithelial cells in papillomas present on UVB-induced Cox-2 flox/flox ; K14Cre + mice were significantly lower than proliferation rates observed for papillomas on control Cox-2 flox/flox mice (Figure 6A).

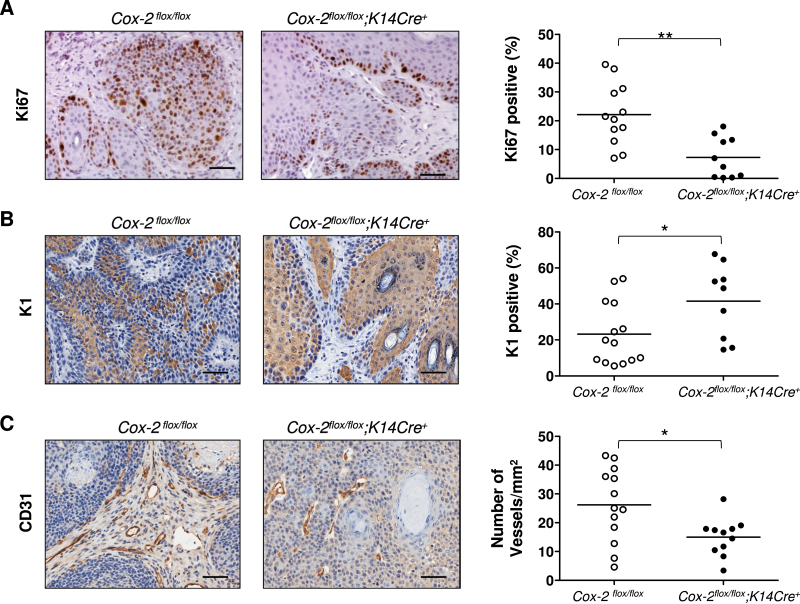

Fig. 6.

Tumor cell proliferation, tumor cell differentiation and tumor vascularization of UVB-induced tumors from mice with an epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion. (A) Ki67 protein expression in tumors of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice. The panels on the left show IHC results. The graph on the right shows quantification of the percentage of Ki67-positive epithelial cells. (B) K1 protein expression in tumors of SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ; K14Cre + mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice. The panels on the left show IHC results. The graph on the right shows quantification of the percentage of K1-positive epithelial cells. (C) Vascularization of tumors from SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice and their littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice. The panels on the left show IHC results for the CD31 endothelial antigen, outlining vessels. The graph on the right shows quantification of the number of vessels per square millimeter of tumor. For all cases, each symbol represents the measurement from a single tumor. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Loss of K1 expression is associated with papilloma progression to higher grade tumors (29). In addition to a decreased proliferation rate, epithelial cell differentiation (evaluated as Keratin1 expression) is significantly increased in tumors of SKH-1 mice with an epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion, in comparison with their Cox-2 flox/flox controls (Figure 6B). Apoptosis, as measured by cleaved Caspase-3 staining, was very infrequent and was not distinguishably different in tumors from SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + and littermate Cox-2 flox/flox mice (Supplementary Figure 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Intrinsic, epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion clearly modifies both proliferation rate and differentiation characteristics of UVB-induced tumors on SKH-1 mice. These data suggest that intrinsic epithelial cell COX-2 expression play a major role in driving both the proliferation and progression of UVB-induced skin tumors.

Vascularization of UVB-induced tumors of SKH-1 Cox-2flox/flox; K14Cre+ mice is reduced compared with tumors present on control Cox-2flox/flox mice

It is possible, and even likely, that elimination of intrinsic COX-2 expression in the epithelial cells of UVB-induced tumors influences the surrounding cells of the microenvironment and consequently the effect of those cells on tumor proliferation, promotion and/or progression. To investigate this possibility, we measured the vascularity of papillomas present on SKH-1 Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice, in which the Cox-2 gene is deleted only in the tumor cells and in papillomas from littermate Cox-2 flox/flox control mice. Vascularity was significantly reduced in papillomas from Cox-2 flox/flox ;K14Cre + mice compared with vascularity in papillomas from control Cox-2 flox/flox mice (Figure 6C).

Discussion

Biochemical, genetic and pharmacologic studies suggest that COX-2 plays a major role in epithelial cancers. COX-2 protein is overexpressed in many human epithelial carcinomas, including bladder, brain, breast, cervix, colorectal, esophagus, head and neck, liver, lung, pancreas, prostate, skin and stomach tumors (10). COX-2 inhibitors have been most extensively tested clinically as chemotherapeutic and preventive agents in patients at risk for colon cancer. Clinical trials with COX-2 inhibitors demonstrate a role for COX-2 in hereditary and spontaneous colon cancer (30), and celecoxib remains an FDA-approved chemopreventive agent for patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Pharmacologic studies with COX-2 inhibitors in mouse models and in clinical trials have implicated elevated COX-2 levels as contributory to lung, breast, prostate, pancreatic, esophageal, skin and stomach cancer and suggested the potential use of coxibs in cancer prevention and chemotherapy (31,32).

Skin tumor induction in mice is the most widely studied preclinical cancer model for relatively obvious reasons—one can easily monitor the time of tumor appearance, the frequency of tumor occurrence and the size of the tumors. In addition, effects of potential enhancers and inhibitors of tumor development can easily be monitored, non-invasively and in real time, by inspection. The most extensively studied model of skin cancer is the DMBA/TPA initiation/promotion paradigm (29,33). UVB irradiation-induced skin cancer in SKH-1 mice shares many of the same experimental advantages but has more extensive genetic restrictions in its applications. Although chemically induced skin cancer and UVB-induced skin cancer are similar in many respects, their skin cancer endpoints are reached by somewhat different pathways. In the DMBA/TPA initiation/promotion model, a well-defined initiation event, a c-Ha-ras gene mutation in an endogenous epithelial cell precursor, occurs in response to DMBA (29). In contrast, no initiating mutation has been clearly defined in the UVB-induced SKH-1 mouse skin cancer model. However, UVB SKH-1 skin cancer more closely resembles the human clinical syndrome; p53 mutations (not common in DMBA/TPA-induced skin tumors) are often associated with both clinical (34,35) and experimental UVB-induced (36,37) premalignant actinic keratoses and SCCs.

COX-1 and COX-2 requirements differ between the DMBA/TPA and UVB skin cancer models. COX-2 expression is required both for DMBA/TPA-induced (28) and for UVB-induced skin cancer (12). COX-1 expression is also essential for DMBA/TPA skin cancer induction (28); however, COX-1 expression is not necessary for UVB-induced skin cancer (11,12).

COX-2 is present in epithelial cells of UVB-induced SKH-1 tumors, and in lymphocytes, histiocytes, macrophages and dermal fibroblasts of the tumor stroma (5). COX-2 inhibition studies and global Cox-2 gene deletion studies cannot identify the cell type(s) in which COX-2 expression is necessary to drive skin tumors; both eliminate COX-2 function in all cells. Our data allow us to reach conclusions that cannot be determined by any protocol other than cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion: (i) intrinsic, cell-autonomous COX-2-dependent prostanoid production in epithelial skin cells plays a major role in UVB-induced tumor formation (Figure 1); (ii) myeloid/macrophage COX-2 expression plays no discernable role in UVB-induced skin tumor induction (Figure 2); (iii) tumor progression from papilloma to SCC is highly, perhaps completely, dependent on intrinsic epithelial tumor cell COX-2 expression (Figure 2C) and (iv) since skin epithelial cell-targeted Cox-2 deletion does not eliminate all UVB-induced skin tumorigenesis, there may be another cell type(s) in which COX-2 function drives these tumors and/or there may exist a COX-2 independent pathway(s) to UVB-induced skin cancer.

Targeted Cox-2 gene deletion has also been examined in mouse pancreatic and breast cancer models but was confined only to the appropriate epithelial cell. In the pancreatic cancer model, the time to 50% survival was more than doubled in mice homozygous for epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion (18). In the breast cancer model, targeted mammary epithelial Cox-2 gene deletion resulted a ~30% increase in the time required for 50% of the mice to develop an observable tumor (38).

Clearly, COX-2 expression in other cell types can modulate biological function. Targeted intestinal epithelial Cox-2 gene deletion did not modify colitis in the mouse model of repeated dextran sodium sulfate administration. In contrast, targeted Cox-2 gene deletion in either endothelial or myeloid/macrophage cells exacerbated dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis (16). Cell-specific COX-2 function is likely to vary substantially from one biological context to another; targeted Cox-2 gene will be required to clarify COX-2 cell-specific roles.

In attempting to understand the role of COX-2 in UVB-irradiated skin tumor induction in SKH-1 mice, the consequences of pharmacologic interventions on skin DNA damage, hyperplasia, proliferation and apoptosis in response to acute UVB exposure have been examined. Treatment of Cox-2 +/+ SKH-1 mice with the COX-2 inhibitor SC-791 (21) or with sulindac (25) reduces acute UVB-induced hyperplasia and increases UVB-induced epidermal cell apoptosis. However, these experiments cannot determine whether these phenotypes, proposed to be causal in the reduced UVB-induced tumor frequency, result from loss of intrinsic, autonomous COX-2 function in skin epithelial cells or result from loss of COX-2 function by other cell types in the skin epithelial cell environment. Our studies determined that the reduction in skin hyperplasia observed previously in UVB-irradiated SKH-1 mice treated with cyclooxygenase inhibitors (21) is due predominantly, if not entirely, to the absence of intrinsic, autonomous COX-2 function in skin epithelial cells (Figure 3). Similarly, a substantial portion, and perhaps all, of the increase in apoptosis observed in UVB-irradiated skin of SKH-1 mice treated with cyclooxygenase inhibitors (21) is also due to loss of intrinsic, endogenous COX-2 expression in skin epithelial cells (Figure 5C). In contrast, several DNA damage responses previously demonstrated in SKH-1 skin following UVB irradiation (22,24) are not modulated by absence of epithelial cell-specific COX-2 (Figure 4B and C). The bulk of the early events mediated by COX-2 in response to acute UVB radiation appear to be associated with intrinsic, epithelial cell-autonomous COX-2 expression/function; COX-2 expression in other cell types seems to play a minor (if any) role.

It seems clear that, in the early responses to UVB irradiation, intrinsic epithelial cell COX-2 expression mediates two major observable changes in skin: hyperplasia and increased apoptosis. Intrinsic COX-2 expression also modulates papilloma promotion and progression; epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion reduces tumor cell proliferation (Figure 6A), enhances tumor cell differentiation (Figure 6B) and prevents papilloma progression to SCCs (Figure 2C). Lao et al. (39), approaching the question of the role of epithelial cell-specific COX-2 expression in skin cancer from a different perspective, also suggest that epithelial cell-intrinsic COX-2 expression plays a major role in skin cancer progression. They compared tumor formation by v-H-ras-transformed Cox-2 +/+ and Cox-2 − /− keratinocytes grafted onto immunodeficient mice; as in our studies with epithelial cell-specific Cox-2 gene deletion, tumor size and incidence were reduced and ‘resulted from reduced keratinocyte proliferation and accelerated keratinocyte differentiation’.

Clearly, it is attractive to suggest that these tumor responses (reduced tumor cell proliferation, enhanced tumor cell differentiation, inability to progress to SCCs) are the direct result of intrinsic Cox-2 gene deletion, perhaps due to an autocrine effect in which epithelial cell COX-2 prostanoids ‘feedback’ on these cells through prostanoid receptors. However, our data demonstrate that the role(s) of epithelial cell-specific COX-2 expression in skin cancer formation is more complicated; targeted epithelial cell-specific elimination of COX-2 expression also reduces vascularization of the tumor, suggesting (i) that epithelial cell COX-2-dependent prostanoids modulate the biology of cells in the tumor microenvironment and (ii) that, in response, the participation in tumor progression of other cells in the microenvironment (e.g. endothelial cells, myeloid cells, myofibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells) is modulated by epithelial cell-specific COX-2 products. These alternatives, such as studies described here to identify the cell type(s) in which COX-2 expression is necessary for UVB skin cancer induction, will require targeted deletion of the Cox-2 gene and the various prostanoid receptors in specific cell types in the tumor microenvironment and examination of the consequences of these targeted deletions on tumorigenesis. Similar concerns for cell-specific roles for all tumor-modulating extracellular signaling molecules, and their receptors, exist and will need to be similarly explored.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

National Institutes of Health (CA 86306 to H.R.H, CN 53300 to S.M.F, GM069338 to E.A.D).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Arthur Catapang for technical help, and the members of the Herschman laboratory and Dr Sotiris Tetradis for helpful discussions.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- DMBA

7,12-dimethylbenz[α]anthracene

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- NSAID

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- UV

ultraviolet.

References

- 1. Benavides F., et al. (2009). The hairless mouse in skin research. J. Dermatol. Sci., 53, 10–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Müller-Decker K. (2011). Cyclooxygenase-dependent signaling is causally linked to non-melanoma skin carcinogenesis: pharmacological, genetic, and clinical evidence. Cancer Metastasis Rev., 30, 343–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rouzer C.A., et al. (2009). Cyclooxygenases: structural and functional insights. J. Lipid Res., 50 (suppl.), S29–S34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith W.L., et al. (2000). Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 145–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. An K.P., et al. (2002). Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in murine and human nonmelanoma skin cancers: implications for therapeutic approaches. Photochem. Photobiol., 76, 73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Athar M., et al. (2001). Ultraviolet B(UVB)-induced cox-2 expression in murine skin: an immunohistochemical study. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 280, 1042–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rundhaug J.E., et al. (2008). Cyclo-oxygenase-2 plays a critical role in UV-induced skin carcinogenesis. Photochem. Photobiol., 84, 322–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johannesdottir S.A., et al. (2012). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of skin cancer: a population-based case-control study. Cancer, 118, 4768–4776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fischer S.M., et al. (1999). Chemopreventive activity of celecoxib, a specific cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, and indomethacin against ultraviolet light-induced skin carcinogenesis. Mol. Carcinog., 25, 231–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anderson W.F., et al. (2003). Potential role of NSAIDs and COX-2 blockade in cancer therapy. In Harris R.E. (ed) COX-2 Blockade in Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 313–340 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pentland A.P., et al. (2004). Cyclooxygenase-1 deletion enhances apoptosis but does not protect against ultraviolet light-induced tumors. Cancer Res., 64, 5587–5591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fischer S.M., et al. (2007). Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is critical for chronic UV-induced murine skin carcinogenesis. Mol. Carcinog., 46, 363–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Greenhough A., et al. (2009). The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis, 30, 377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pentland A.P., et al. (1999). Reduction of UV-induced skin tumors in hairless mice by selective COX-2 inhibition. Carcinogenesis, 20, 1939–1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ishikawa T.O., et al. (2006). Conditional knockout mouse for tissue-specific disruption of the cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2) gene. Genesis, 44, 143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ishikawa T.O., et al. (2011). Cox-2 deletion in myeloid and endothelial cells, but not in epithelial cells, exacerbates murine colitis. Carcinogenesis, 32, 417–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Narasimha A.J., et al. (2010). Absence of myeloid COX-2 attenuates acute inflammation but does not influence development of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E null mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 30, 260–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hill R., et al. (2012). Cell intrinsic role of COX-2 in pancreatic cancer development. Mol. Cancer Ther., 11, 2127–2137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kietzmann M., et al. (1990). The mouse epidermis as a model in skin pharmacology: influence of age and sex on epidermal metabolic reactions and their circadian rhythms. Lab. Anim., 24, 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akunda J.K., et al. (2007). Cyclooxygenase-2 deficiency increases epidermal apoptosis and impairs recovery following acute UVB exposure. Mol. Carcinog., 46, 354–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tripp C.S., et al. (2003). Epidermal COX-2 induction following ultraviolet irradiation: suggested mechanism for the role of COX-2 inhibition in photoprotection. J. Invest. Dermatol., 121, 853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Svobodová A.R., et al. (2012). DNA damage after acute exposure of mice skin to physiological doses of UVB and UVA light. Arch. Dermatol. Res., 304, 407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. RajnochováSvobodová A., et al. (2013). Effects of oral administration of Lonicera caerulea berries on UVB-induced damage in SKH-1 mice. A pilot study. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci., 12, 1830–1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lu Y.P., et al. (1999). Time course for early adaptive responses to ultraviolet B light in the epidermis of SKH-1 mice. Cancer Res., 59, 4591–4602 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Athar M., et al. (2004). Photoprotective effects of sulindac against ultraviolet B-induced phototoxicity in the skin of SKH-1 hairless mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 195, 370–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fuchs E. (2009). Finding one’s niche in the skin. Cell Stem Cell, 4, 499–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhu S., et al. (1999). C/EBPbeta modulates the early events of keratinocyte differentiation involving growth arrest and keratin 1 and keratin 10 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 7181–7190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tiano H.F., et al. (2002). Deficiency of either cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 or COX-2 alters epidermal differentiation and reduces mouse skin tumorigenesis. Cancer Res., 62, 3395–3401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abel E.L., et al. (2009). Multi-stage chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin: fundamentals and applications. Nat. Protoc., 4, 1350–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DuBois R.N. (2003). Cyclooxygenase-2 and colorectal cancer. Prog. Exp. Tumor Res., 37, 124–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ghosh N., et al. (2010). COX-2 as a target for cancer chemotherapy. Pharmacol. Rep., 62, 233–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fischer S.M., et al. (2011). Coxibs and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in animal models of cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila)., 4, 1728–1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kemp C.J. (2005). Multistep skin cancer in mice as a model to study the evolution of cancer cells. Semin. Cancer Biol., 15, 460–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brash D.E., et al. (1991). A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 10124–10128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Giglia-Mari G., et al. (2003). TP53 mutations in human skin cancers. Hum. Mutat., 21, 217–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li G., et al. (1995). Ultraviolet radiation induction of squamous cell carcinomas in p53 transgenic mice. Cancer Res., 55, 2070–2074 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Viarisio D., et al. (2011). E6 and E7 from beta HPV38 cooperate with ultraviolet light in the development of actinic keratosis-like lesions and squamous cell carcinoma in mice. PLoS Pathog., 7, e1002125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Markosyan N., et al. (2011). Deletion of cyclooxygenase 2 in mouse mammary epithelial cells delays breast cancer onset through augmentation of type 1 immune responses in tumors. Carcinogenesis, 32, 1441–1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lao H.C., et al. (2012). Genetic ablation of cyclooxygenase-2 in keratinocytes produces a cell-autonomous defect in tumor formation. Carcinogenesis, 33, 2293–2300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.