Abstract

Gap junctions (GJs) contribute to cerebral vasodilation, vasoconstriction, and, perhaps, to vascular compensatory mechanisms, such as autoregulation. To explore the effects of traumatic brain injury (TBI) on vascular GJ communication, we assessed GJ coupling in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle (VSM) cells subjected to rapid stretch injury (RSI) in vitro and VSM in middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) harvested from rats subjected to fluid percussion TBI in vivo. Intercellular communication was evaluated by measuring fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). In VSM cells in vitro, FRAP increased significantly (p<0.05 vs. sham RSI) after mild RSI, but decreased significantly (p<0.05 vs. sham RSI) after moderate or severe RSI. FRAP decreased significantly (p<0.05 vs. sham RSI) 30 min and 2 h, but increased significantly (p<0.05 vs. sham RSI) 24 h after RSI. In MCAs harvested from rats 30 min after moderate TBI in vivo, FRAP was reduced significantly (p<0.05), compared to MCAs from rats after sham TBI. In VSM cells in vitro, pretreatment with the peroxynitrite (ONOO−) scavenger, 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)prophyrinato iron[III], prevented RSI-induced reductions in FRAP. In isolated MCAs from rats treated with the ONOO− scavenger, penicillamine, GJ coupling was not impaired by fluid percussion TBI. In addition, penicillamine treatment improved vasodilatory responses to reduced intravascular pressure in MCAs harvested from rats subjected to moderate fluid percussion TBI. These results indicate that TBI reduced GJ coupling in VSM cells in vitro and in vivo through mechanisms related to generation of the potent oxidant, ONOO−.

Key words: : cell culture, fluid percussion injury, gap junctions, middle cerebral arteries, rapid stretch injury, smooth muscle cells, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Cerebral arteries dilate or constrict in response to a wide variety of stimuli, including changes in systemic arterial pressure,2,3 PaCO24,5 PaO2, extracellular pH,6 brain metabolic activity,7 and hematocrit.8 These and other aspects of normal cerebral vascular function are described in detail in numerous reviews.9–16 Traumatic brain injury (TBI) impairs or abolishes many cerebral vascular compensatory responses in humans and experimental animals.9,17–19 Increased vulnerability to secondary insults may be due, in part, to traumatic cerebral vascular injury resulting in impaired compensatory responses to changes in levels of arterial blood pressure, carbon dioxide, oxygen, and so on.9,20–22

Putative causes of traumatic cerebral vascular dysfunction include reactive oxygen species (e.g., superoxide23 or other oxidants, such as peroxynitrite [ONOO−],24–26 endothelin,27 nociceptin/orphanin FQ,28 or other opiate receptors ligands,29 cytochrome P450 metabolites [e.g., 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid]30 and many others reviewed elsewhere).22,31,32 Although the effects of free radicals and oxidants, vasoactive agents, receptor ligands, etc., on cerebral vascular reactivity are well known, the precise mechanisms through which these substances impair cerebral vascular function are less clear.

Gap junctions (GJs) are membrane specializations providing low-resistance pathways that permit the passage of ions as well as small molecules, such as cyclic nucleotides and intracellular signaling molecules,33,34 between cells. GJs coordinate vascular smooth muscle (VSM) function by communicating changes in membrane potential and intracellular Ca2+ between adjacent VSM cells.35 Observations that GJ Inhibitors attenuate myogenic tone,36 acetylcholine (ACh)-mediated vasodilation37 and conducted vasodilation38 in cerebral arteries suggest that GJ communication between VSM cells plays an important role in cerebral arterial tone and vascular reactivity.

Peroxynitrite is a powerful oxidant that is synthesized from abnormally high levels of nitric oxide (NO) and the superoxide anion radical.39 Peroxynitrite exposure caused relaxation in feline pial arteries,40 constriction in isolated rodent middle cerebral arteries (MCAs)25 and impaired function of Ca2+-activated K+ channels41 in vascular endothelial (ECs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Peroxynitrite added to normal (uninjured) isolated MCAs resulted in concentration-dependent reductions in vasodilatory responses to progressive reductions in intravascular pressure and calcitonin gene-related peptide and cromakalim.24 Nitrotyrosine, produced when OONO− nitrates tyrosine residues in proteins, has been detected in brain42–44 and spinal cord45 after TBI, suggesting that central nervous system trauma results in production of OONO−.

To test the hypothesis that TBI, perhaps through the actions of OONO− or other oxidants, impairs cerebral vascular reactivity by reducing GJ coupling between VSM cells, the following experiments were designed to determine whether 1) GJ inhibitors decreased dilator responses to progressive reductions in intravascular pressure (IVP) in normal (uninjured) cerebral arteries, 2) stretch injury in vitro or fluid percussion TBI in vivo reduced GJ communication between VSM cells, 3) ONOO− reduced GJ coupling between normal (uninjured) VSM cells, 4) ONOO− scavengers improved VSM GJ communication after stretch injury in vitro or fluid percussion TBI in vivo, and 5) ONOO− scavengers improved dilator responses to reduced IVP in MCA segments harvested from rats subjected to fluid percussion TBI in vivo.

Methods

Reagents

The A7r5 VSM cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Tissue culture reagents were obtained from Mediatech, Inc. (Herndon, VA). Fetal bovine serum was obtained from GIBCO by Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)prophyrinato iron[III] (FeTPPS) was from Calbiochem (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and 5-carboxyfluorescein diacetate (CFDA) was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO).

Fluid percussion traumatic brain injury

All experimental protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of The University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, TX). Male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing 350–400 g) were anesthetized with isoflurane in an anesthetic chamber, intubated, and mechanically ventilated with 1.5–2.0% isoflurane in O2/room air (70:30) using a volume ventilator (EDCO Scientific, Chapel Hill, NC). Polyethylene cannulae were placed in a femoral artery and vein for arterial pressure monitoring and drug infusion, respectively. Rectal and brain temperatures were monitored using telethermometers (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Brain temperature, measured through a small craniotomy adjacent to the injury site, was kept constant at 37°C using a thermostatically controlled water blanket (Gaymar, Orchard Park, NY). Rats were prepared for fluid percussion TBI as previously described.46,47 Briefly, rats were placed in a stereotaxic frame and the scalp was incised along the mid-line. A 4-mm hole was trephined into the skull 2 mm to the right of the mid-sagittal suture, mid-way between lambda and bregma, and a modified LuerLok syringe hub was placed over the exposed dura and bonded in place with cyanoacrylic adhesive and covered with dental acrylic.

Middle cerebral artery preparation

Thirty minutes after TBI, anesthetized rats were decapitated, brains were removed, and MCAs were harvested. Tissue around the MCAs was cut with microfine scissors. MCAs were gently reflected, beginning at the circle of Willis, and continuing dorsally for 4–5 mm. Connective tissue was gently removed from the MCA. Cerebral arteries were mounted in an arteriograph (Living Systems Instrumentation, St. Albans, VT) by inserting micropipettes into the lumen at either end and securing the vessel with nylon sutures, as previously described.24,48 The mounted arterial segment was bathed in physiological salt solution of the following composition (mM): mM: NaCl, 130; KCl, 4.7; MgSO4, 7H2O, 1.17; glucose, 5; CaCl2, 1.50, and NaHCO3, 15. When gassed with a mixture of 95% air and 5% CO2, the solution had a pH of 7.4. After mounting, MCAs were warmed from room temperature to 37°C and allowed to equilibrate for 60 min with IVP set at 50 mmHg. A pressure transducer between micropipettes and reservoir bottles was used to monitor IVP across the MCA segment. Vessels were magnified with an inverted microscope equipped with a video camera and a monitor. Arterial diameter was measured using a video scaler calibrated with an optical micrometer. Before testing for myogenic responses to changes in IVP, contractility and endothelial function were tested using 30 mM of K+ or ACh (10–5 M), respectively. Dilator responses were tested by decreasing IVP in 20-mmHg increments with a 5-min equilibration period at each pressure level before diameter measurements were made.

Smooth muscle cell culture

The A7r5 VSM cell line was maintained in tissue culture flasks in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% heated (56°C for 30 min) FBS, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 mg/mL of streptomycin. Cells were fed every second day with fresh serum-containing medium and grown to confluence at 37°C in 5% CO2 in air. When light microscopic examination showed cells to be confluent, they were plated on tissue culture wells with silastic bottoms (FlexPlates; Flexwell International, McKeesport, PA). To accomplish this, confluent VSM cells were treated with trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; 0.25% trypsin/0.03% EDTA). Lifted cells were then transferred to a plastic tube, centrifuged, counted, and 2×105 cells in 1 mL of DMEM-containing 10% FBS were plated on collagen-coated silastic membranes (25 mm diameter and 2 mm thickness) that formed the bottom surface of each well in a six-well FlexPlate (Flexwell International).

Rapid stretch injury

Confluent cells grown in FlexPlates (Flexwell International) were injured using a model 94A Cell Injury Controller (Commonwealth Biotechnology, Richmond, VA), as previously described.49 Briefly, the device delivers a graded pulse of compressed gas, which transiently deforms silastic membranes and adherent cells to degrees controlled by the pulse pressure. Uninjured control wells underwent the same manipulations, except that they did not receive rapid stretch injury (RSI). In all of the experiments on cultured VSM cells, each treatment condition was repeated three times and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was measured in 20–30 VSM cells in each plate.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

GJ coupling between VSM cells in vitro, or MCAs harvested from rats subjected to fluid percussion TBI in vivo, was assessed by measuring FRAP using confocal fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss LSM510; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Cultured VSM cells or MCAs were loaded for 15 min at room temperature with PBS solution containing the membrane-permeant molecule, 5,6-CDFA (5 μg/mL). This lipophilic compound is hydrolyzed by cytoplasmic esterases to 6-carboxyfluorescein, a hydrophilic derivative that accumulates inside cells. After washing twice, excess extracellular fluorogenic ester was removed. For measurements of FRAP in isolated MCAs, after loading with CFDA, MCAs were fixed on cover slips mounted in steel cover-slip holders that were mounted in a microincubator regulated at 37°C by a temperature controller.

The fluorescent dye of selected cells was photobleached by applying strong light pulses from an argon laser set at 488 nm. Fluorescence intensity was recorded in bleached cells before and 10 or 2 min after photobleaching for VSM cells or MCA segments, respectively. In each experiment, two labeled isolated cells, left unbleached, served as a reference for loss of fluorescence resulting from repeated scanning and dye leakage. When bleached cells were coupled by GJ channels to unbleached, contiguous cells, fluorescence recovery followed an exponential time course. Fluorescence recovery was expressed as returned fluorescence as a percentage of baseline fluorescence.

Experimental design

Effects of gap junctions on vasodilatory responses in middle cerebral arteries harvested from normal (uninjured) rats

MCAs were harvested from adult, male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=6 per group) and prepared for measurements of arterial diameters. Vasodilatory responses to progressive reductions in IVP were performed before and after treatment with the GJ inhibitors: SR141716A (3 μM); 18β glycyrrhetinic acid (18-GA; 200 μM) or carbenoxolone (CBX; 200 μM). Because SR141716A is a cannabanoid 1 receptor (CB1) antagonist as well as a GJ inhibitor, the effect of LY320135 (5, 10, and 20 μM), a CB1 antagonist without effects on GJ,50 also was tested.

Effects of gap junction inhibitors on intercellular gap junction communication between vascular smooth muscle cells in middle cerebral artery segments

To determine whether the nonspecific GJ inhibitor, CBX, and specific gap peptides reduced GJ coupling between VSM cells in MCA segments ex vivo, adult, male Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane in an anesthetic chamber, decapitated, and MCAs were harvested and prepared for FRAP measurements, as described above. All arteries were incubated in CFDA and randomly assigned to one of three groups (n=6/group): an untreated control; a group incubated with a mixture of gap peptides (37,43Gap27, 40Gap27, and 43Gap26); and a group incubated with the nonspecific GJ inhibitor, CBX. GJ coupling was assessed by measuring FRAP, as described above.

Effects of severity of rapid stretch injury on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro

Effects of increasing levels of stretch injury on intercellular GJ communication between VSM cells in vitro were measured by subjecting A7r5 VSM cells grown on FlexPlates (Flexwell International), as described above and subjected to mild, moderate, or severe RSI (membrane deformations of 4.2, 5.5, or 6.8 mm, respectively). GJ coupling was assessed by measuring FRAP 2 h after RSI or sham RSI.

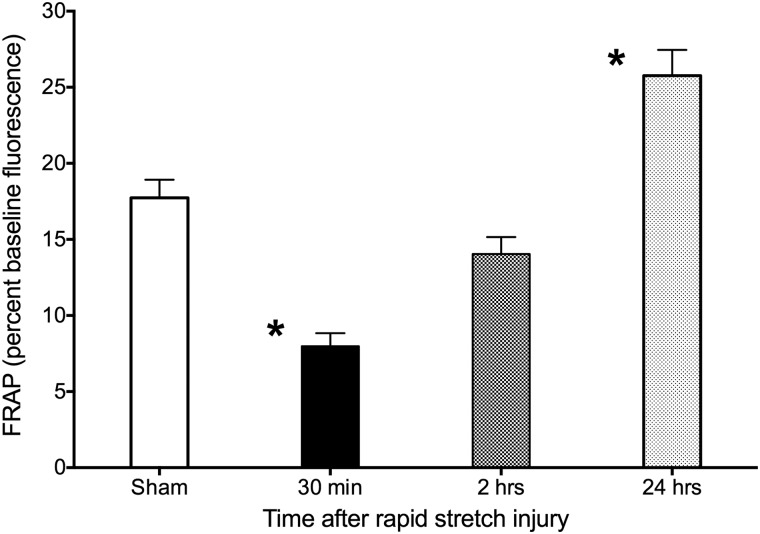

Effects of moderate rapid stretch injury on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells 30 min or 2 or 24 h postinjury

To determine effects of time after RSI on GJ communication between VSM cells in vitro, A7r5 cells were subjected to moderate (5.5-mm membrane deformation) RSI and GJ coupling was assessed by measuring FRAP 30 min or 2 or 24 h postinjury.

Effects of peroxynitrite on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro

The powerful oxidant, ONOO−, produced in brain and vascular tissue after fluid percussion TBI,42 inhibits dilator responses to reduced IVP in MCAs.24 To determine whether ONOO− inhibited GJ communication between VSM cells in vitro, A7r5 cells were exposed to 1.0 or 5.0 μM of ONOO− alone or ONOO− and FeTPPS, a ONOO− scavenger and decomposition catalyst that does not complex with NO and exhibits minimal superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic activity.51 GJ coupling was assessed by measuring FRAP 2 h later.

Effects of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)prophyrinato iron[III] on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells after rapid stretch injury

The contribution of ONOO− to impaired GJ coupling after RSI was explored by determining whether treatment with the ONOO− scavenger, FeTPPS, improved GJ communication between cultured VSM cells subjected to RSI. VSM cells were grown on FlexPlates (Flexwell International), treated with 25 μM of FeTPPS, and subjected to RSI or sham injury (no RSI). As a positive control, uninjured VSM cells were treated with the GJ inhibitor, 18-GA (200 μM). GJ coupling was assessed by measuring FRAP 30 min after RSI.

Effects of fluid percussion traumatic brain injury in vivo on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells in isolated, pressurized middle cerebral arterial segments

To determine whether fluid percussion TBI in vivo inhibits GJ coupling between VSM cells in MCA segments, adult, male, Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, prepared for fluid percussion TBI as described above, and randomly assigned to receive moderate (2.0 atmospheres [atm]) fluid percussion TBI or sham injury (n=6/group). Thirty minutes after TBI, isoflurane levels were increased to 4%, rats were decapitated, and MCAs were harvested and prepared for FRAP measurements, as previously described.

Effects of penicillamine on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells in middle cerebral artery segments from rats after fluid percussion traumatic brain injury

Effects of treatment with an ONOO− scavenger after fluid percussion TBI on GJ communication in VSM cells were determined in MCA segments harvested from rats subjected to fluid percussion TBI and treated with penicillamine methyl ester, a membrane-permeable ONOO− inhibitor. Adult, male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=4) were anesthetized with 2.0 isoflurane and subjected to moderate (2.2 atm) or severe (2.9 atm) parasagittal fluid percussion TBI, as described above. Immediately after TBI, rats were treated with penicillamine methyl ester (10 mg/kg, intravenously [i.v.]), and, 30 min later, MCAs were harvested and prepared for measurements of FRAP.

Effects of treatment with the peroxynitrite scavenger, penicillamine, on vasodilatory responses to reduced intravascular pressure in middle cerebral arteries from rats after fluid percussion traumatic brain injury

To determine effects of treatment with an ONOO− scavenger after fluid percussion TBI on dilator responses to reduced IVP in MCA segments, adult, male, Sprague-Dawley rats (n=6 per group) were anesthetized with 2.0% isoflurane and subjected to moderate (2.0 atm) or severe (2.8 atm) parasagittal fluid percussion TBI or sham TBI, treated with penicillamine methyl ester (10 mg/kg, i.v.), and, 30 min later, MCAs were harvested and prepared for measurements of vasodilatory responses to reduced IVP, as described above.

Statistical analysis

All data in the text and figures are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean. Data from FRAP experiments were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. Data from the measurements of pial arterial diameters were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of gap junction inhibitors on vasodilatory responses in middle cerebral arteries harvested from normal (uninjured) rats

Vasodilation in response to reduced IVP in normal (uninjured) MCAs was significantly (Fig. 1; p<0.05 pretreatment vs. treatment) reduced by 18-GA, CBX, and SR141716A. Dilation in response to reduced IVP was not influenced by 5–20 μM of LY320135, the CB1 receptor antagonist without effects on GJ coupling.

FIG. 1.

Effects of GJ inhibitors 18-GA and carbenoxolone, the CB1/GJ inhibitor, SR141716A, or the CB1 inhibitor, LY320135, on MCA diameters during sequential reductions in intravascular pressure. 18-GA, carbenoxolone, and SR141716A reduced myogenic vasodilation, whereas LY320135, a CB1 receptor antagonist without effects on GJ, did not. *p<0.05 versus pretreatment diameters. GJ, gap junction; 18-GA, 18β glycyrrhetinic acid; CB1, cannabinoid 1; MCA, middle cerebral artery.

Effects of gap junction inhibitors on intercellular gap junction communication between vascular smooth muscle in middle cerebral arterial segments

FRAP was reduced significantly in MCA segments incubated with a mixture of GJ-inhibiting peptides (37,43Gap27, 40Gap27, and 43Gap26) or CBX (Fig. 2; p<0.05, vehicle vs. CBX; p<0.001, vehicle vs. gap peptides). Incubation with gap peptides reduced FRAP to a significantly greater degree than incubation with CBX (Fig. 2; p<0.01, gap peptides vs. CBX).

FIG. 2.

Gap junction coupling between smooth muscle cells in isolated middle cerebral arterial segments was reduced by cabenoxolone (CBX) and the specific gap peptide inhibitors, Gap27,37,43 Gap27,40 and Gap26.43 Gap junction communication was assessed by measuring fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). *p<0.05, vehicle versus CBX; **p<0.01, vehicle versus gap peptides.

Effects rapid stretch injury on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro

Mild RSI (4.2 mm deformation) resulted in significant increases in FRAP (Fig. 3; p<0.05, sham vs. 4.2 RSI). Moderate or severe RSI decreased FRAP significantly (Fig. 3; p<0.05, sham vs. 5.5 RSI; p<0.05, sham vs. 6.8 RSI).

FIG. 3.

Effects of increasing levels of rapid stretch injury (RSI) on fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. As the injury level increased, FRAP decreased. FeTPPS pretreatment improved FRAP significantly. Data represent mean±standard error of the mean of 20–30 cells from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, sham versus 4.2, 5.5, or 6.8; #p<0.01, 6.8 versus 6.8+FeTPPS; **p<0.05, sham versus 18-GA. FeTPPS, 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)prophyrinato iron[III]; 18-GA, 18β glycyrrhetinic acid.

Effects of moderate rapid stretch injury on fluorescence recovery after photobleaching in vascular smooth muscle cells 30 min or 2 or 24 h postinjury

Moderate RSI resulted in significant reductions in FRAP 30 min postinjury (Fig. 4; p<0.001, sham vs. 30 min) and significant increases in FRAP 24 h postinjury (P<0.001, sham vs. 24 h). FRAP reductions 2 h post-RSI were not statistically significant.

FIG. 4.

Effects of time on fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) after moderate (5.5-mm membrane deformation) rapid stretch injury in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Thirty minutes after injury, FRAP decreased significantly, recovered partially after 2 h, then increased above sham values 24 h after injury. Data represent mean±standard error of the mean of 20–30 cells from three independent experiments. *p<0.001, sham versus 30 min or 24 h.

Effects of peroxynitrite on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro

Exposure to 1.0 or 5.0 μM of ONOO− resulted in significant reductions in FRAP in A7r5 VSM cells in vitro (Fig. 5; p<0.01, 0.0 vs. 1.0 or 5.0 μM of ONOO−). SMCs exposed to 1.0 μM of ONOO− along with 25 μM of FeTPPS exhibited fluorescence recovery significantly higher than those from VSM cells exposed to 1.0 μM of ONOO− alone (Fig. 5; p<0.05, 1.0 vs. 1.0 μM plus FeTPPS). In contrast, FeTPPS had no effect on VSM cells exposed to 5.0 μM of ONOO−.

FIG. 5.

Gap junction coupling (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching; FRAP) was significantly reduced in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro by 1.0 and 5.0 μM of ONOO−. FeTPPS (25 μM) reversed the effects of 1.0, but not 5.0, μM of ONOO−. *p<0.01 versus 0.0 μMONOO−; **p<0.05 1.0 μM of ONOO− versus 1.0 μM of ONOO−+FeTPPS. ONOO−, peroxynitrite; FeTPPS, 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)prophyrinato iron[III].

Effects of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)prophyrinato iron[III] on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells after rapid stretch injury

Treatment of A7r5 VSM cells with FeTPPS after severe (6.8 mm deformation) RSI resulted in significant increases in FRAP (Fig. 3; p<0.01, 6.8 vs. 6.8 plus FeTPPS). Although VSM cells treated with FeTPPS after moderate RSI (5.5 mm deformation) exhibited increases in FRAP to levels not significantly different from FRAP in sham-injured VSM cells, FRAP in FeTPPS-treated and untreated cells were not statistically significant after moderate RSI. Treatment of uninjured cells with the GJ inhibitor, 18-GA, resulted in significant reductions in FRAP (Fig. 3; p<0.05, sham vs. 18-GA).

Effects of fluid percussion traumatic brain injury in vivo on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells in isolated, pressurized middle cerebral artery segments

SMCs in MCA segments harvested 30 min postinjury from rats subjected to moderate or severe FPI exhibited significant reductions in FRAP (Fig. 6; p<0.05, sham vs. moderate TBI; p<0.05, sham vs. severe TBI).

FIG. 6.

Gap junction communication (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching; FRAP) between smooth muscle cells was significantly reduced in middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) harvested from rats subjected to moderate (MOD) or severe (SEV) fluid percussion TBI. FRAP was significantly higher in smooth muscle cells in MCAs harvested from rats treated with the peroxynitrite scavenger, penicillamine methyl ester, immediately after TBI. Data represent mean±standard error of the mean of 10–15 smooth muscle cells in four MCAs in each group. *p<0.05, sham versus Mod TBI or Sev TBI; **p<0.05, Mod TBI versus Mod TBI+penicillamine; #p<0.05, Sev TBI versus Sev TBI+penicillamine. TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Effects of penicillamine on gap junction coupling in vascular smooth muscle in middle cerebral arteries from rats after fluid percussion traumatic brain injury

Treatment with the ONOO− scavenger, penicillamine (10 mg/kg, i.v.), immediately postinjury increased FRAP significantly in VSM cells in MCAs harvested 30 min after moderate or severe fluid percussion TBI (Fig. 6; p<0.05, moderate TBI vs. moderate TBI plus penicillamine; p<0.05, severe TBI vs. severe TBI plus penicillamine).

Effects of treatment with the peroxynitrite scavenger, penicillamine, on vasodilatory responses to reduced intravascular pressure in middle cerebral arteries from rats after fluid percussion traumatic brain injury

Arterial diameters increased during progressive reductions in IVP in MCAs harvested from rats after sham injury (Fig. 7). In contrast, vasodilator responses were significantly reduced in MCAs harvested from rats subjected to moderate fluid percussion TBI (Fig. 7; p<0.05, sham vs. TBI). Treatment with penicillamine methyl ester (10 mg/kg, i.v.) significantly (p<0.05, TBI vs. TBI plus penicillamine) increased vasodilation during progressive reductions in IVP in MCAs harvested from rats subjected to moderate TBI.

FIG. 7.

Treatment with penicillamine methly ester (10 mg/kg) 5 min postinjury restored vasodilation during sequential reductions in intravascular pressure in middle cerebral arterial segments harvested from rats subjected to moderate fluid percussion TBI. *p<0.05, TBI versus sham or TBI+penicillamine.

Discussion

Our results indicated that 1) dilator responses to progressive reductions in IVP in isolated, pressurized MCA segments were reduced or abolished by GJ inhibitors, 2) nonspecific (CBX) and specific (gap peptides 37,43Gap27, 40Gap27, and 43Gap26) GJ inhibitors significantly reduced intercellular GJ communication between VSM cells in isolated, pressurized MCA segments, 3) mild RSI increased, whereas moderate and severe RSI decreased, GJ communication between VSM cells in vitro, 4) GJ communication between VSM cells in vitro was significantly reduced 30 min after, and significantly increased 24 h after, RSI, 5) ONOO− (1.0 and 5.0 μM) significantly reduced GJ communication between VSM cells in vitro, 6) GJ coupling of VSM cells was significantly reduced in MCAs harvested from rats subjected to moderate or severe fluid percussion TBI in vivo, and 7) the ONOO−, scavengers, FeTPPS or penicillamine, significantly improve GJ communication between VSM cells after RSI in vitro or fluid percussion injury in vivo, respectively. These novel observations support the hypothesis that post-traumatic cerebral vascular dysfunction is a result, in part, of the trauma-induced inhibition of GJ communication between VSM cells in cerebral arteries. Further, our observations that ONOO− inhibited GJ coupling between VSM cells in vivo and in vitro and our previous report that ONOO− reduced dilator responses to reduced IVP to the same degree as fluid percussion TBI24 support the hypothesis that traumatic cerebral vascular dysfunction is a result of the effects of ONOO− on cerebral vascular GJ communication.

GJs are plasma membrane microdomains that permit rapid exchange of ions and metabolites between adjacent cells.52 GJs are made up of connexin (Cx) molecules, each of which is a polypeptide with four membrane-spanning segments separated by two extracellular and one intracellular loop.53 Selectivity and permeability of GJ depends on Cx composition,54,55 but, in general, they are permeable to molecules less than 1.2 kDa. Although at least 21 Cx have been identified in mammals,56 only Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45 are expressed in vascular tissue.57–59 Vascular ECs are extensively coupled by GJs.60 The hyperpolarization of ECs by endothelium-dependent vasodilators61 is transmitted electrotonically to VSM by myoendothelial GJ comprised of Cx37 and Cx4362 (for review of myoendothelial GJ, see previous reports62–64).

GJs play an important role in the control of tissue blood flow. Segal and During65 and de Wit66 reported that propagated vasodilation and constriction in response to iontophoretically applied ACh or norepinephrine, respectively, were not inhibited by muscarinic or α-adrenergic receptor antagonists, but were reduced by GJ inhibitors. Taylor and colleagues67 observed that the GJ inhibitor, 18α-GA, inhibited ACh relaxation by 90% in preconstricted rabbit iliac arteries. Ujiie and colleagues37 reported that NO- and prostanoid-independent vasodilatory effects of ACh were dependent on GJ integrity in rabbit MCAs. In rat aorta and superior mesenteric artery, GJ inhibition with the peptide inhibitor, 43Gap27, inhibited ACh vasodilation and the N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester–insensitive component of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-induced relaxation.68 Other peptide GJ inhibitors, such as 40Gap27, 37,40Gap26, 43Gap26, and 37,43Gap27, blocked myoendothelial and homocellular smooth muscle GJ communication69,70 without nonspecific effects on endothelial hyperpolarization or smooth muscle constriction or relaxation.50,68 In rabbit ear arteries, 37,43Gap27 and 43Gap26 (specific inhibitors of Cx43) inhibited ACh-evoked endothelium-derived hyperpolarization factor–type dilation.37 The GJ inhibitors, heptanol or 18α-GA, reduced myogenic vasoconstriction in response to increased IVP in isolated, pressurized rat MCAs.36 Our results, indicating that the GJ inhibitors, SR141716A, 18-GA, and CBX, reduced vasodilation in response to reduced IVP in isolated MCAs, support and extend the hypothesis that GJs are important contributors to normal cerebral vascular dilator and constrictor responses.

GJ communication can be altered by a variety of normal and pathological stimuli. Protein kinases A71 and C (PKC)72 phosphorylated and uncoupled GJs in rat hippocampal astroctyes. Intercellular GJ coupling was reduced in cultured cortical astroctyes by NO and arachidonic acid.73,74 TBI may impair GJ coupling because TBI initiates many of the injury processes that lead to GJ dysfunction. Fluid percussion TBI markedly increased brain tissue levels of prostaglandins75,76 and superoxide anion radicals77,78 and activated PKC.79 As noted above, oxidant stress and PKC activation led to GJ uncoupling,72,80 indicating that TBI produces conditions that have been associated with intercellular GJ communication.

Although this is the first evidence of post-traumatic impairment of GJ coupling in the cerebral circulation, traumatic alterations in GJs in neurons and astrocytes have been reported. Weight-drop traumatic injury to organotypic hippocampal slices resulted in enhanced GJ communication (FRAP), but also increased lesion volume in wild-type versus Cx43 null mice.81 In addition, GJ inhibitors improved electrophysiological recovery in these injured hippocampal slices.81 Ohsumi and colleagues82 reported that Cx43 immunoreactivity increased 24 h after lateral fluid percussion TBI and remained elevated for 72 h in reactive astrocytes in the injured hippocampus. Cx 36 immunoreactivity in CA3 also increased significantly 1 h postinjury, but returned to control levels within 72 h.82 In a subsequent study, Ohsumi and colleagues83 observed that phosphorylated Cx43 immunoreactivity and protein expression were increased in astrocytes in rat hippocampus 1, 6, and 24 h after lateral fluid percussion TBI.

These results and others in models of cerebral ischemia84,85 suggest that increases in Cx expression and GJ coupling, particularly those comprised of Cx36 and Cx43, contribute to traumatic and ischemic neuronal injury. In contrast, Chang and colleagues86 reported that, whereas transection of motor nerves in adult cats and rats had no effect on Cx36, Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, or Cx45 RNA expression, re-establishment of interneuronal GJ communication in axotomized motor neurons contributed to neuronal viability.

The mechanisms of traumatic GJ dysfunction in neurons and neuroglia have not been established with certainty, but glutamate excitotoxicity appears to play a role. The excessive release of extracellular glutamate resulting from photothrombotic ischemia in mice in vivo or oxygen-glucose deprivation in neuronal cultures in vitro resulted in increased Cx36 protein and RNA expression and interneuronal GJ coupling.87 Glutamate-induced increases in Cx36 expression and GJ communication were mediated by group II metabotropic glutamate receptors.87,88 Because TBI is associated with the immediate release of excessive glutamate concentrations,89–91 it is likely that post-traumatic increases in Cx expression, GJ coupling, and subsequent neuronal injury are mediated, in part, by glutamate.

Our observations that the ONOO− scavengers, FeTPPS and penicillamine, improved GJ coupling in VSM cells after stretch injury in vitro or fluid percussion TBI in vivo suggest that post-traumatic ONOO− generation contributes to injury-induced GJ dysfunction. FeTPPS is one of a family of thiol-containing metalloporphyrin catalytic ONOO− scavengers that capture and redirect, rather than decompose, the oxidative potential of ONOO−.92 Another metalloporphyrin, MnTBAP (Mn (III) tetrakis [4-benzoic acid]-porphyrin), reduced neuronal injury and nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity after traumatic spinal cord injury in rats.45 Hall and colleagues93 observed that penicillamine improved motor behavior (grip test) after weight-drop TBI in mice. Interestingly, penicillamine methyl ester, a more membrane-permeable form of penicillamine, was no more effective at improving motor performance than the penicillamine that remained in the vasculature, suggesting that vascular ONOO− scavenging is an important component of the therapeutic effect of penicillamine.93 Further support for ONOO−-mediated vascular damage is provided by evidence that ONOO− produced dose-dependent constriction and impaired vasoconstrictor responses to serotonin25 and reduced vasodilatory responses to progressive reductions in IVP and calcitonin gene-related peptide or cromakalim (activators of ATP-dependent potassium channels)24 in isolated, pressurized rat MCAs.

Moderate and severe RSI resulted in significant reductions in GJ communication in A7r5 VSM cells (Fig. 3). McKinney and colleagues94 reported level-dependent injury (i.e., decrease in ability to exclude propidium iodide [PI]) in aortic EC injury after RSI in vitro. RSI also is associated with immediate, though transient, increases in intracellular calcium levels in cultured neurons95 and astrocytes,96,97 which are related to the severity of injury. These results are consistent with the level-dependent nature of GJ dysfunction after RSI. We also observed that mild RSI was associated with significant increases in FRAP. Although the reasons for increased GJ coupling after mild RSI are uncertain, it may be related to the effects of NO on GJ communication and the effects of injury on NO levels. GJ coupling in ECs98 and myoendothelial GJ communication in endothelial and VSM in vitro99 was increased by exogenous NO donors (for review, see a previous report100). We9 and others101,102 reported that endothelial NO synthase protein expression increased significantly within 24 h after moderate fluid percussion9,101 or impact acceleration102 TBI in rats. Direct measurements of brain tissue NO levels indicated that NO increased significantly after controlled cortical impact.103 Thus, the increased GJ communication that we observed in VSM cells may have been a result of the effects of increased NO production on GJs after mild RSI. Although moderate and severe RSI also would be associated with increased NO activity and formation, likely substantial increases in superoxide levels would have occurred as well.77,104 Because post-traumatic increases in NO105 and ROS106,107 are level dependent, moderate and severe RSI likely produced higher levels of NO, superoxide, and the resulting ONOO− than mild RSI. Thus, after moderate and severe injury, the conversion of NO to ONOO− may have reduced the stimulatory effects of NO on GJ coupling and directly inhibited GJ communication. In contrast, mild RSI may have been associated with formation of superoxide levels too low to produce significant quantities of ONOO− and, therefore the stimulatory effects of NO on GJs may have predominated.

GJ communication in VSM cells was reduced significantly 30 min after severe RSI, but increased significantly 24 h after the same level of stretch injury (Fig. 4). McKinney and colleagues94 observed that neuronal and glial cells as well as ECs subjected to RSI recovered the ability to exclude PI within 24 h of injury, with ECs showing the most rapid recovery. Unlike neurons and glia, ECs were protected by pretreatment with polyethylene glycol-conjugated superoxide dismutase (PEG-SOD) before RSI. Thus, the increase in FRAP that we observed 24 h post-RSI may have been evidence of the recovery reported by McKinney and colleagues.94 Evidence that PEG-SOD improved viability only in ECs suggests that oxidants contribute to stretch-induced vascular, but not neuronal or glial, injury, an observation that would be consistent with our hypothesis that ONOO− plays an important role in vascular cell GJ dysfunction after stretch injury in vitro. It is important to note, however, that McKinney and colleagues94 observed recovery of EC viability within 2 h, whereas improved GJ coupling in the present study was not observed until 24 h postinjury. Additionally, because McKinney and colleagues94 reported on viability in vascular endothelial, rather than GJ function in VSM, cells, the degree to which their observations are relevant to the present study is unclear.

The in vitro RSI experiments were performed using A7r5 VSM cells from rat thoracic aorta.108 A7r5 cells express the smooth-muscle–specific proteins, α-actin and desmin.108,109 As with SMCs in cerebral arteries in vivo, A7r5 cells express Cx43 and Cx40, separately or colocalized within the same GJ plaques,69,110 and Cx45.111 Although A7r5 cells do not express Cx37 protein,110 Cx37 protein expression in vivo has been described primarily in ECs and myoendothelial junctions.57,112 In a previous study,113 we observed expression of messenger RNA (mRNA) for Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45 in cerebral vascular endothelial cells and SMCs, but were unable to detect Cx37 protein expression (Western blots) in either cell type. Thus, although GJ communication in A7r5 VSM cells in vitro may not be identical to that in VSM cells in vivo,109 Cx protein and mRNA expression is similar, if not identical, A7r5 cells form stable, functional Cx43 GJ channels109 and intercellular coupling by Cx43 and Cx40 GJ in A7r5 SMCs is inhibited significantly by the combination of the specific gap peptides, 43Gap26 and 40Gap27.69 Together, these data suggest that the results from our studies on A7r5 VSM cells are relevant to primary VSM cells in vitro.

In summary, our observations that TBI or GJ inhibitors reduce cerebral vasodilatory responses to reduced IVP suggest the GJ communication is an important component of normal cerebral vasodilatory function and that impairment of GJ coupling contributes to post-traumatic cerebral vascular dysfunction. Our results that ONOO− scavengers reduced impairment of GJ communication between VSM cells after fluid percussion TBI and RSI support the hypothesis that traumatic cerebral vascular dysfunction is a result, in part, of ONOO−-mediated interruption of GJ communication in cerebral arteries. Further studies of the effects of ONOO− scavengers on cerebral artery reactivity and CBF are required to confirm the role of ONOO− and GJ communication in traumatic cerebral vascular injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the technical assistance provided by Violeta Chen and Jeremy Cowart. The authors also thank Jordan Kicklighter and Christy Perry for their editorial assistance. This work was supported by the Moody Foundation and NS19355 (to D.S.D.) from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Braak H., and Braak E. (1991). Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fog M. (1937). Cerebral circulation: the reaction of the pial arteries to a fall in blood pressure. Arch. Neurol. Psychiat. 23, 1097–1120 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lassen N.A. (1959). Cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in man. Physiol. Rev. 39, 183–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kontos H.A., Wei E.P., Navarri R.M., Levasseur J.E., Rosenblum W.I., and Patterson J.L. (1978). Responses of cerebral arteries and arterioles to acute hypotension and hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. 234, H371–H383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff H.G., and Lennox W.G. (1930). Cerebral circulation. XII. The effect on pial vessels of variations in the oxygen and carbon dioxide content of the blood, in: Oxygen Measurements in Blood and Tissues. Payne J.P., and Hill D.W. (eds). Churchill: London, pps. 205–214 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kontos H.A., Raper A.J., and Patterson J.L. (1977). Analysis of vasoactivity of local pH, PCO2, and bicarbonate on pial vessels. Stroke 8, 358–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuschinsky W. (1982). Coupling between functional activity, metabolism and blood flow in the brain: state of the art. Microcirculation 2, 357–378 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudak M.L., Koehler R.C., Rosenberg A.A., Traystman R.J., and Jones M.D., Jr, (1986). Effect of hematocrit on cerebral blood flow. Am. J. Physiol. 251, H63–H70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeWitt D.S., and Prough D.S. (2003). Traumatic cerebral vascular injury: the effects of concussive brain injury on the cerebral vasculature. J. Neurotrauma 20, 795–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edvinsson L., Mackenzie E.T., and McCullock J. (1993). Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. Raven Press: New York [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faraci F.M., and Brian J.E., Jr, (1994). Nitric oxide and the cerebral circulation. Stroke 25, 692–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kontos H.A. (1981). Regulation of the cerebral circulation. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 43, 397–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen L.J., and Holstein-Rathlou N.H. (2013). The vascular conducted response in cerebral blood flow regulation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33, 649–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koller A., and Toth P. (2012). Contribution of flow-dependent vasomotor mechanisms to the autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. J. Vasc. Res. 49, 375–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi M., Hang C., Zhu L., and Shi J. (2011). Involvement of endothelial-derived relaxing factors in the regulation of cerebral blood flow. Neurol. Sci. 32, 551–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attwell D., Buchan A.M., Charpak S., Lauritzen M., Macvicar B.A., and Newman E.A. (2010). Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature 468, 232–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golding E.M., Steenberg M.L., Contant C.F., Krishnappa I., Robertson C.S., and Bryan J., R.M. (1999). Cerebrovascular reactivity to CO2 and hypotension after mild cortical impact injury. Am. J. Physiol. 277, H1457–H1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kochanek P.M., Clark R.S.B., Ruppel R.A., Adelson P.D., Bell M.J., Whalen M.J., Robertson C.L., Satchell M.A., Seiderg N.A., Marion D.W. and Jenkins L.W. (2000). Biochemical, cellular, and molecular mechanisms in the evolution of secondary damage after severe traumatic brain injury in infants and children: lessons learned from the bedside. Ped. Crit. Care Med. 1, 4–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rangel-Castill L., Gasco J., Nauta H.J.W., Okonkwo D.O., and Robertson C.S. (2008). Cerebral pressure autoregulation in traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg. Focus 24, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeWitt D.S., Jenkins L.W., and Prough D.S. (1995). Enhanced vulnerability to secondary ischemic insults after experimental traumatic brain injury. New Horizons 3, 376–383 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golding E.M. (2002). Sequelae following traumatic brain injury. The cerebrovascular perspective. Br. Res. Rev. 38, 377–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werner C., and Engelhard K. (2007). Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br. J. Anaesth. 99, 4–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kontos H.A., Wei E.P., Povlishock J.T., Dietrich W.D., Magiera C.J., and Ellis E.F. (1980). Cerebral arteriolar damage by arachidonic acid and prostaglandin G2. Science 209, 1242–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeWitt D.S., Mathew B.P., Chaisson J.M., and Prough D.S. (2001). Peroxynitrite reduces vasodilatory responses to reduced intravascular pressure, calcitonin gene-related peptide and cromakalim in isolated middle cerebral arteries. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 21, 253–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elliott S.J., Lacey D.J., Chilian W.M., and Brzezinska A.K. (1998). Peroxynitrite is a contractile agonist of cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 275, H1585–H1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faraci F.M., and Heistad D.D. (1998). Regulation of the cerebral circulation: role of endothelium and potassium channels. Physiol. Rev. 78, 53–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstead W.M. (1996). Role of endothelin in pial artery vasoconstriction and altered responses to vasopressin after brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 85, 901–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armstead W.M. (2000). NOC/oFQ contributes to age-dependent impairment of NMDA-induced cerebrovasodilation after brain injury. Am. J. Physiol. 279, H2188–H2195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armstead W.M., and Kurth C.D. (1994). The role of opioids in newborn pig fluid percussion brain injury. Br. Res. 660, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imig J.D., Simpkins A.N., Renic M., and Harder D.R. (2011). Cytochrome P450 eicosanoids and cerebral vascular function. Exp. Rev. Mol. Med. 13, e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bramlett H.M., and Dietrich W.D. (2004). Pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia and brain trauma: Similarities and differences. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 24, 133–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattson M.P., and Scheff S.W. (1994). Endogenous neuroprotection factors and traumatic brain injury: mechanisms of action and implications for therapy. J. Neurotrauma 11, 3–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruzzone R., White T.W., and Paul D.L. (1996). Connections with connexins: the molecular basis of direct intercellular signaling. Eur. J. Biochem. 238, 1–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodenough D.A., and Paul D.L. (2009). Gap junctions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a002578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christ G.J., Spray D.C., el-Sabban M., Moore L.K., and Brink P.R. (1996). Gap junctions in vascular tissues: evaluating the role of intercellular communication in the modulation of vasomotor tone. Circ. Res. 79, 631–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagaud G., Karicheti V., Knot H.J., Christ G.J., and Laher I. (2002). Inhibitors of gap junctions attenuate myogenic tone in cerebral arteries. Am. J. Physiol. 283, H2177–H2186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ujiie H., Chaytor A.T., Bakker L.M., and Griffith T.M. (2003). Essential role of gap junctions in NO- and prostanoid-independent relaxations evoked by acetylcholine in rabbit intracerebral arteries. Stroke 34, 544–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagher P., and Segal S.S. (2011). Regulation of blood flow in the microcirculation: role of conducted vasodilation. Acta Physiol. 202, 271–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beckman J.S., Beckman T.W., Chen J., Marshall P.A., and Freeman B.A. (1990). Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. PNAS 87, 1620–1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei E.P., Kontos H.A., and Beckman J.S. (1996). Mechanisms of cerebral vasodilation by superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and peroxynitrite. Am. J. Physiol. 271, H1262–H1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brzezinska A., Chilian W.M., and Elliott S.J. (1998). Peroxynitrite inhibits K+currents and causes freshly isolated cerebral artery smooth muscles to contract. FASEB J 12, A1001 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Avila M.A., Sell S.L., Y K., Prough D.S., Hellmich H.L., Velasco M., and DeWitt D.S. (2008). L-arginine decreases fluid-percussion injury-induced neuronal nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 28, 1733–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall E.D., Detloff M.R., Johnson K., and Kupina N.C. (2004). Peroxynitrite-mediated protein nitration and lipid peroxidation in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 21, 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mesenge C., Charriaut-Marlangue C., Verrecchia C., Allix M., Boulu R.R., and Plotkine M. (1998). Reduction of tyrosine nitration after N(omega)-nitro-L-arginine-methylester treatment of mice with traumatic brain injury. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 353, 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu D., Ling X., Wen J., and Liu J. (2000). The role of reactive nitrogen species in secondary spinal cord injury: formation of nitric oxide, peroxynitrite, and nitrated protein. J. Neurochem. 75, 2144–2154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeWitt D.S., Smith T.G., Deyo D.S., Miller K.R., Uchida T., and Prough D.S. (1997). L-arginine or superoxide dismutase prevents or reverse cerebral hypoperfusion after fluid-percussion traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 14, 223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixon C.E., Lyeth B.G., Povlishock J.T., Findling R.L., Hamm R.J., Marmarou A., Young H.F., and Hayes R.L. (1987). A fluid percussion model of experimental brain injury in the rat. J. Neurosurg. 67, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bryan R.M., Cherian L., and Robertson C.S. (1995). Regional cerebral blood flow after controlled cortical impact injury in rats. Anesth. Analg. 80, 687–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ellis E.F., McKinney J.S., Willoughby K.A., Liang S., and Povlishock J.T. (1995). A new model for rapid stretch-induced injury of cells in culture: characterization of the model using astrocytes. J. Neurotrauma 12, 325–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chaytor A.T., Martin P.E., Evans W.H., Randall M.D., and Griffith T.M. (1999). The endothelial component of cannabinoid-induced relaxation in rabbit mesenteric artery depends on gap junctional communication. J. Physiol. (London) 520, 539–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Misko T.P., Highkin M.K., Veenhuizen A.W., Manning P.T., Stern M.K., Currie M.G., and Salvemini D. (1998). Characterization of the cytoprotective action of peroxynitrite decomposition catalysts. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15646–15653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans W.H., and Martin P.E. (2002). Gap junctions: structure and function (review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 19, 121–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jongsma H.J., and Wilders R. (2000). Gap junctions in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 86, 1193–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bevans C.G., Kordel M., Rhee S.K., and Harris A.L. (1998). Isoform composition of connexin channels determines selectivity among second messengers and uncharged molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2808–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niessen H., Harz H., Bedner P., Kramer K., and Willecke K. (2000). Selective permeability of different connexin channels to the second messenger inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. J. Cell Sci. 113, 1365–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sohl G., and Willecke K. (2004). Gap junctions and the connexin protein family. Cardiovasc. Res. 62, 228–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li X., and Simard J.M. (1999). Multiple connexins form gap junction channels in rat basilar artery smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 84, 1277–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li X., and Simard J.M. (2001). Connexin45 gap junction channels in rat cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 281, H1890–H1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Little T.L., Beyer E.C., and Duling B.R. (1995). Connexin43 and connexin40 gap junctional proteins are present in arteriolar smooth muscle and endothelium in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 268, H729–H739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haas T.L., and Duling B.R. (1997). Morphology favors an endothelial cell pathway for longitudinal conduction within arterioles. Microvasc. Res. 53, 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nilius B., and Droogmans G. (2001). Ion channels and their functional role in vascular endothelium. Physiol. Rev. 81, 14155–11459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haddock R.E., and Grayson T.H. (2006). Endothelial coordination of cerebral vasomotion via myoendothelial gap junctions containing connexins 37 and 40. Am. J. Physiol. 291, H2036–H2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Wit C., and Griffith T.M. (2010). Connexins and gap junctions in the EDHF phenomenon and conducted vasomotor responses. Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 459, 897–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bény J.-L., Koenigsberger M., and Sauser R. (2006). Role of myoendothelial communication on arterial vasomotion. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291, H2036–H2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Segal S.S., and Duling B.R. (1989). Conduction of vasomotor responses in arterioles: a role for cell-to-cell coupling? Am. J. Physiol. 256, H838–H845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Wit C. (2004). Connexins pave the way for vascular communication. News Physiol. Sci. 19, 148–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taylor H.J., Chaytor A.T., Evans W.H., and Griffith T.M. (1998). Inhibition of the gap junctional component of endothelium-dependent relaxations in rabbit iliac artery by 18-alpha glycyrrhetinic acid. Br. J. Pharmacol. 125, 1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaytor A.T., Evans W.H., and Griffith T.M. (1998). Central role of heterocellular gap junctional communication in endothelium-dependent relaxations of rabbit arteries. J. Physiol. (London) 508, 561–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chaytor A.T., Martin P.E., Edwards D.H., and Griffith T.M. (2001). Gap junctional communication underpins EDHF-type relaxations evoked by ACh in the rat hepatic artery. Am. J. Physiol. 280, H2441–H2450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Griffith T.M., Chaytor A.T., Taylor H.J., Giddings B.D., and Edwards D.H. (2002). cAMP facilitates EDHF-type relaxations in conduit arteries by enhancing electrotonic conduction via gap junctions. PNAS 99, 6392–6397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rorig B., Klausa G., and Sutor B. (1995). Dye coupling between pyramidal neurons in developing rat prefrontal and frontal cortex is reduced by protein kinase A activation and dopamine. J. Neurosci. 15, 7386–7400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Konietzko U., and Muller C.M. (1994). Astrocytic dye coupling in rat hippocampus: topography, developmental onset, and modulation by protein kinase C. Hippocampus 4, 297–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bolanos J.P., and Medina J.M. (1996). Induction of nitric oxide synthase inhibits gap junction permeability in cultured rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 66, 2091–2099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rorig B., and Sutor B. (1996). Nitric oxide-stimulated increase in intracellular cGMP modulates gap junction coupling in rat neocortex. Neuroreport 7, 569–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DeWitt D.S., Kong D.L., Lyeth B.G., Jenkins L.W., Hayes R.L., Wooten E.D., and Prough D.S. (1988). Experimental traumatic brain injury elevates brain prostaglandin E2 and thromboxane B2 levels in rats. J. Neurotrauma 5, 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ellis E.F., Wright K.F., Wei E.P., and Kontos H.A. (1981). Cyclooxygenase products of arachidonic acid metabolism in cat cerebral cortex after experimental concussive brain injury. J. Neurochem. 37, 892–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fabian R.H., DeWitt D.S., and Kent T.A. (1998). The 21-aminosteroid U-74389G reduces cerebral superoxide anion concentration following fluid percussion injury of the rat. J. Neurotrauma 15, 433–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kontos H.A., and Wei E.P. (1986). Superoxide production in experimental brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 64, 803–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Armstead W.M. (1999). Superoxide generation links protein kinase C activation to impaired ATP- sensitive K+channel function after brain injury. Stroke 30, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martinez A.D., and Saez J.C. (1999). Arachidonic acid-induced dye uncoupling in rat cortical astrocytes is mediated by arachidonic acid byproducts. Br. Res. 816, 411–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frantseva M.V., Kokarovtseva L., Naus C.G., Carlen P.L., MacFabe D., and Perez Velazquez J.L. (2002). Specific gap junctions enhance the neuronal vulnerability to brain traumatic injury. J. Neurosci. 22, 644–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ohsumi A., Nawashiro H., Otani N., Ooigawa H., Toyooka T., Yano A., Nomura N., and Shima K. (2006). Alteration of gap junction proteins (connexins) following lateral fluid percussion injury in rats. Acta Neurochir. 96, 148–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ohsumi A., Nawashiro H., Otani N., Ooigawa H., Toyooka T., and Shima K. (2010). Temporal and spatial profile of phosphorylated connexin43 after traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 27, 1255–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cotrina M.L., Kang J., Lin J.H., Bueno E., Hansen T.W., He L., Liu Y., and Nedergaard M. (1998). Astrocytic gap junctions remain open during ischemic conditions. J. Neurosci. 18, 2520–2537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin J.H., Weigel H., Cotrina M.L., Liu S., Bueno E., Hansen A.J., Hansen T.W., Goldman S., and Nedergaard M. (1998). Gap-junction-mediated propagation and amplification of cell injury. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 494–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chang Q., Pereda A., Pinter M.J., and Balice-Gordon R.J. (2000). Nerve injury induces gap junctional coupling among axotomized adult motor neurons. J. Neurosci. 20, 674–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang Y., Song J.-H., Denisova J.V., Park W.-M., Fontes J.D., and Belousov A.B. (2012). Neuronal gap junction coupling Is regulated by glutamate and plays critical role in cell death during neuronal injury. J. Neurosci. 32, 713–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Park W.M., Y. W., Park S., Denisova J.V., Fontes J.D., and Belousov A.B. (2011). Interplay of chemical neurotransmitters regulates developmental increase in electrical synapses. J. Neurosci. 31, 5909–5920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Faden A.I., Demediuk P., Panter S.S., and Vink R. (1989). The role of excitatory amino acids and NMDA receptors in traumatic brain injury. Science 244, 798–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Katayama Y., Maeda T., Koshinaga M., Kawamata T., and Tsubokawa T. (1995). Role of excitatory amino acid-mediated ionic fluxes in traumatic brain injury. Br. Pathol. (Zurich) 5, 427–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Katayama Y., Becker D.P., Tamura T., and Ikezaki K. (1990). Early cellular swelling in experimental traumatic brain injury: a phenomenon mediated by excitatory amino acids. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. (Wien) 51, 271–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Crow J.P. (2000). Peroxynitrite scavenging by metalloporphyrins and thiolates. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 28, 1487–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hall E.D., Kupina N.C., and Althaus J.S. (1999). Peroxynitrite scavengers for the acute treatment of traumatic brain injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 8890, 462–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McKinney J.S., Willoughby K.A., Liang S., and Ellis E.F. (1996). Stretch-induced injury of cultured neuronal, glial, and endothelial cells. Effect of polyethylene glycol-conjugated superoxide dismutase. Stroke 27, 934–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weber J.T., Rzigalinski B.A., Willoughby K.A., Moore S.F., and Ellis E.F. (1999). Alterations in calcium-mediated signal transduction after traumatic injury of cortical neurons. Cell Cal. 26, 289–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rzigalinski B.A., Liang S., McKinney J.S., Willoughby K.A., and Ellis E.F. (1997). Effect of Ca2+on in vitro astrocyte injury. J. Neurochem. 68, 289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rzigalinski B.A., Weber J.T., Willoughby K.A., and Ellis E.F. (1998). Intracellular free calcium dynamics in stretch injured astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 70, 2377–2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hoffmann A., Gloe T., Pohl U., and Zahler S. (2003). Nitric oxide enhances de novo formation of endothelial gap junctions. Cardiovasc. Res. 60, 421–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Straub A.C., Billaud M., Johnstone S.R., Best A.K., Yemen S., Dwyer S.T., Looft-Wilson R., Lysiak J.J., Gaston B., Palmer L., and Isakson B.E. (2011). Compartmentalized connexin 43 s-nitrosylation/denitrosylation regulates heterocellular communication in the vessel wall. Arteriosler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 399–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Looft-Wilson R.C., Billaud M., Johnstone S.R., Straub A.C., and Isakson B.E. (2012). Interaction between nitric oxide signaling and gap junctions: effects on vascular function Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 1895–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cobbs C.S., Fenoy A., Bredt D.S., and Noble L.J. (1997). Expression of nitric oxide synthase in the cerebral microvasculature after traumatic brain injury in the rat. Br. Res. 751, 336–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lu Y.C., Liu S., Gong Q.Z., Hamm R.J., and Lyeth B.G. (1997). Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase potentiates hypertension and increases mortality in traumatically brain-injured rats. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 30, 125–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cherian L., Goodman J.C., and Robertson C.S. (2000). Brain nitric oxide changes after controlled cortical impact injury in rats. J. Neurophysiol. 83, 2171–2178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fabian R.H., DeWitt D.S., and Kent T.A. (1995). In vivo detection of superoxide anion production by the brain using a cytochrome C electrode. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 15, 242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tuzgen S., Tanriover N., Uzan M., Tureci E., Tanriverdi T., Gumustas K., and Kuday C. (2003). Nitric oxide levels in rat cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, and brainstem after impact acceleration head injury. Neurol Res. 25, 31–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marklund N., Clausen F., Lewander T., and Hillered L. (2001). Monitoring of reactive oxygen species production after traumatic brain injury in rats with microdialysis and the 4-hydroxybenzoic acid trapping method. J. Neurotrauma 18, 1217–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Inci S., Ozcan O.E., and Kilinc K. (1998). Time-level relationship for lipid peroxidation and the protective effect of alpha-tocopherol in experimental mild and severe brain injury. Neurosurgury 43, 330–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kimes B.W., and Brandt B.L. (1976). Characterization of two putative smooth muscle cell lines from rat thoracic aorta. Exp. Cell Res. 98, 349–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Moore L.K., Beyer E.C., and Burt J.M. (1991). Characterization of gap junction channels in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 260, C975–C981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Martin P.E.M., Wall C., and Griffith T.M. (2005). Effects of connexin-mimetic peptides on gap junction functionality and connexin expression in cultured vascular cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 144, 617–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Laing J.G., Westphale E.M., Engelmann G.L., and Beyer E.C. (1994). Characterization of the gap junction protein, connexin45. J. Membr. Biol. 139, 31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.de Wit C., and Griffith T.M. (2010). Connexins and gap junctions in the EDHF phenomenon and conducted vasomotor responses. Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 459, 897–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Avila M.A., Sell S.L., Hawkins B.E., Hellmich H.L., Boone D.R., Crookshanks J.M., Prough D.S., and DeWitt D.S. (2011). Cerebrovascular connexin expression: effects of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 28, 1803–1811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]