Abstract

It has been demonstrated that α-synuclein can aggregate and contribute to the pathogenesis of some neurodegenerative diseases and it is capable of hindering autophagy in neuronal cells. Here, we investigated the implication of α-synuclein in the autophagy process in primary human T lymphocytes. We provide evidence that: (i) knocking down of the α-synuclein gene resulted in increased autophagy, (ii) autophagy induction by energy deprivation was associated with a significant decrease of α-synuclein levels, (iii) autophagy inhibition by 3-methyladenine or by ATG5 knocking down led to a significant increase of α-synuclein levels, and (iv) autophagy impairment, constitutive in T lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, was associated with abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates. These results suggest that α-synuclein could be considered as an autophagy-related marker of peripheral blood lymphocytes, potentially suitable for use in the clinical practice.

Keywords: α-synuclein, T lymphocytes, autophagy, systemic lupus erythematosus, lymphoma

Synucleins are a family of soluble proteins common to vertebrates known to be expressed in neural crest-derived cells (neuronal cells, neuroglial cells and melanocytic cells) and in certain tumors.1 In particular, the most studied synuclein, that is, the α-synuclein, is primarily found in neuronal tissue but also in other cell types including peripheral blood lymphocytes.2, 3 Alpha-synuclein exists in monomers and oligomers that, in neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's Disease (PD), dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy, have been demonstrated to form insoluble fibril aggregates.4, 5 In these disorders, known as synucleinopathies, macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy), the form of intracellular phagocytosis in which a cell actively consumes and recycles damaged organelles or misfolded proteins by encapsulating them into autophagosomes,6, 7 seems to have a key pathogenetic role. In particular, it has been suggested that the complex framework of events leading to autophagic process could be defective in these diseases so that abnormal α-synuclein protein aggregates are formed and accumulate.8, 9 Conversely, it has strikingly been observed that α-synuclein overexpression is capable of hindering autophagy at a very early stage of autophagosome formation.10 To date, however, all these important insights are derived from studies carried out in neuronal cells, and the implication of α-synuclein in autophagy modulation in cells other than neurons has not been investigated yet. In particular, as autophagy process has a fundamental role in the immune system integrity and function, including lymphocyte differentiation and metabolism, we decided to investigate whether α-synuclein could be involved in the lymphocyte autophagy.11 In fact, the impairment of autophagy has been recently linked to several immune-mediated diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).12, 13, 14, 15, 16 To note, an increased level of α-synuclein in T lymphocytes from patients with SLE, resistant to autophagy induction, has been reported.16 In this study, we provide evidence that α-synuclein can actually be considered as a key player in the mechanism of autophagy of primary human T lymphocytes, suggesting a clinical application of this molecule for monitoring autophagy level in freshly isolated T cells.

Results

On the role of α-synuclein in T-lymphocyte autophagy

Alpha-synuclein silencing increases autophagy levels in T lymphocytes

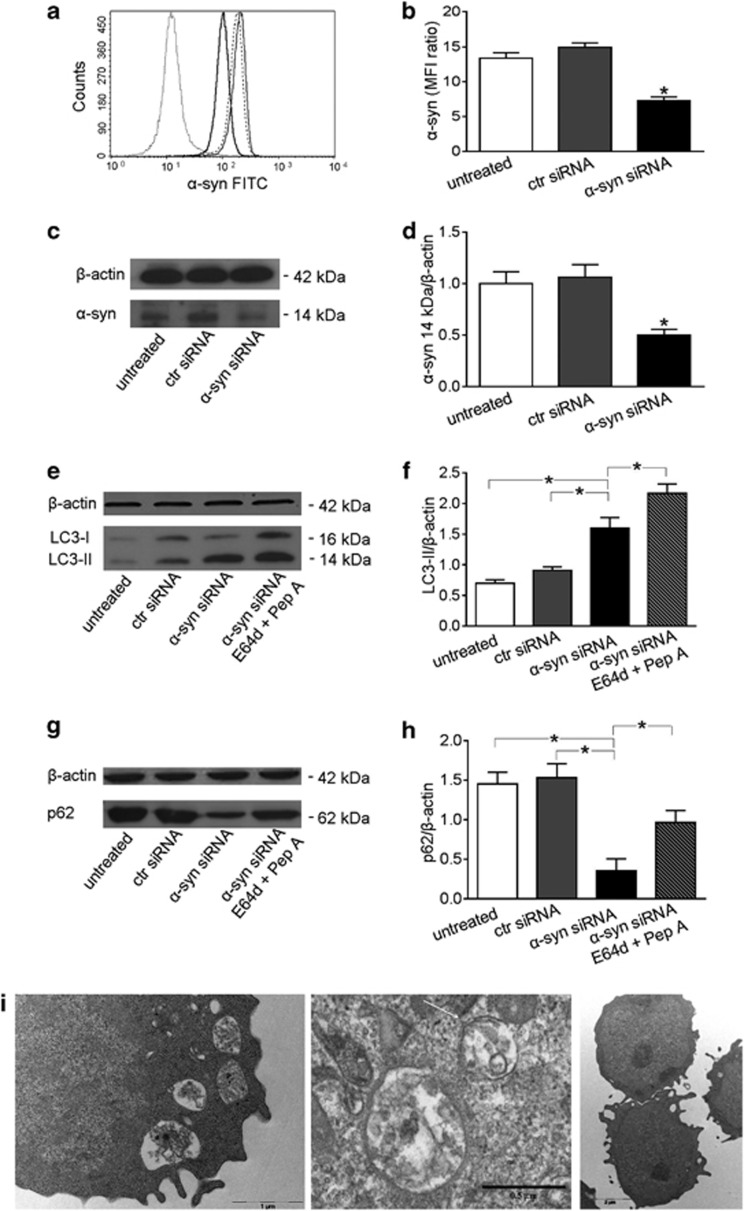

Alpha-synuclein has been reported as a negative regulator of autophagy in neuronal cells.10 More recently, we relieved an increased level of α-synuclein expression in T lymphocytes from patients with SLE, a disease characterized by autophagy impairment, in comparison with that detected in T lymphocytes from healthy subjects.16 Hence, we asked if this molecule could have a regulatory function in the autophagy of T lymphocytes. To this purpose, we decided to transfect these cells with specific siRNA to knock down α-synuclein gene. In our experimental conditions, 24 h after siRNA addition, α-synuclein expression decreased by about 50%, as assessed by both flow cytometry (Figures 1a and b) and western blot (Figures 1c and d) analyses, whereas LC3-II levels significantly increased in comparison with control siRNA-transfected (+44%) and non-transfected (+64%) cells (P<0.01 in both cases; Figures 1e and f). In order to assess the rate of autophagosome formation (i.e., autophagic flux), we also analyzed LC3-II levels in the presence of the lysosomal protease inhibitors E64d and pepstatin A, which block LC3-II/autophagosome degradation.17 In the presence of these inhibitors, we observed a further increase of LC3-II levels in α-synuclein siRNA-transfected T cells (Figures 1e and f). Accordingly, p62 protein, another accredited marker of autophagy that accumulates when autophagy is inhibited and decreases when autophagy is induced,18 was decreased by about 75% in α-synuclein siRNA-transfected T cells as compared with control siRNA-transfected and non-transfected T cells (P<0.01 in both cases; Figures 1g and h). This significant decrease of p62 levels was not detectable in α-synuclein siRNA-transfected T cells when the lysosomal protease inhibitors E64d and pepstatin A were added (Figures 1g and h).

Figure 1.

Alpha-synuclein (α-syn) silencing in T lymphocytes. (a) Flow cytometry analysis of α-syn expression 24 h after siRNA transfection. Isotype control (ctr) staining is represented by the dotted line. Non-transfected (untreated) anti-α-syn-labeled T lymphocytes are represented by the broken line, those transfected with ctr siRNA by the gray-solid line, and those transfected with α-syn siRNA by the black-solid line. A representative experiment out of five is shown. (b) Values of α-syn/isotype ctr mean fluorescence intensity ratio are reported. *P<0.05 versus other experimental conditions. (c) Western blot of cell lysates obtained from T lymphocytes non-transfected (untreated), transfected with ctr siRNA and transfected with α-syn siRNA. Blots shown are representative of five independent experiments. (d) Densitometry analysis of monomeric α-syn levels relative to β-actin is shown. Values are expressed as means±S.D. *P<0.05 versus other experimental conditions. (e) Western blot analysis of LC3-II in T lymphocytes treated as follows: (i) non-transfected (untreated), (ii) transfected with ctr siRNA, (iii) transfected with α-syn siRNA and (iv) transfected with α-syn siRNA in the presence of E64d and pepstatin A (Pep A). Blots shown are representative of five independent experiments. (f) Densitometry analysis of LC3-II levels relative to β-actin is shown. Values are expressed as means±S.D. *P<0.05. (g) Western blot analysis of p62 in T lymphocytes (i) non-transfected (untreated), (ii) transfected with ctr siRNA, (iii) transfected with α-syn siRNA and (iv) transfected with α-syn siRNA in the presence of E64d and Pep A. Blots shown are representative of five independent experiments. (h) Densitometry analysis of p62 levels relative to β-actin is shown. Values are expressed as means±S.D. *P<0.05 versus other experimental conditions. (i) Transmission electron micrographs representative of T cells transfected with α-syn siRNA (left and middle panels) and with ctr siRNA (right panel). Note the presence of typical autophagic vacuoles in α-syn siRNA-transfected T cells (left). At high magnification (middle panel), degraded membranes and cell debris are visible in the vacuoles. The arrow indicates a double membrane. FITC, fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity

In order to further characterize these results, ultrastructural analyses were carried out at the transmission electron microscope. The presence of autophagic vacuoles containing structures that can clearly be identified as cytoplasmic, such as partially degraded endoplasmic reticulum and cell debris, was observed in α-synuclein knocked down T cells (Figure 1i). Morphometric evaluation of these samples, as stated in Materials and methods section, indicated that the percentage of cells with clear signs of autophagy was significantly higher (+23%) in α-synuclein knocked down T cells in comparison with control siRNA-transfected T cells. All in all, the current set of experiments suggested that α-synuclein could have a direct inhibitory role in T-cell autophagy.

On the role of autophagy in α-synuclein degradation in T lymphocytes

Induction of autophagy leads to α-synuclein degradation

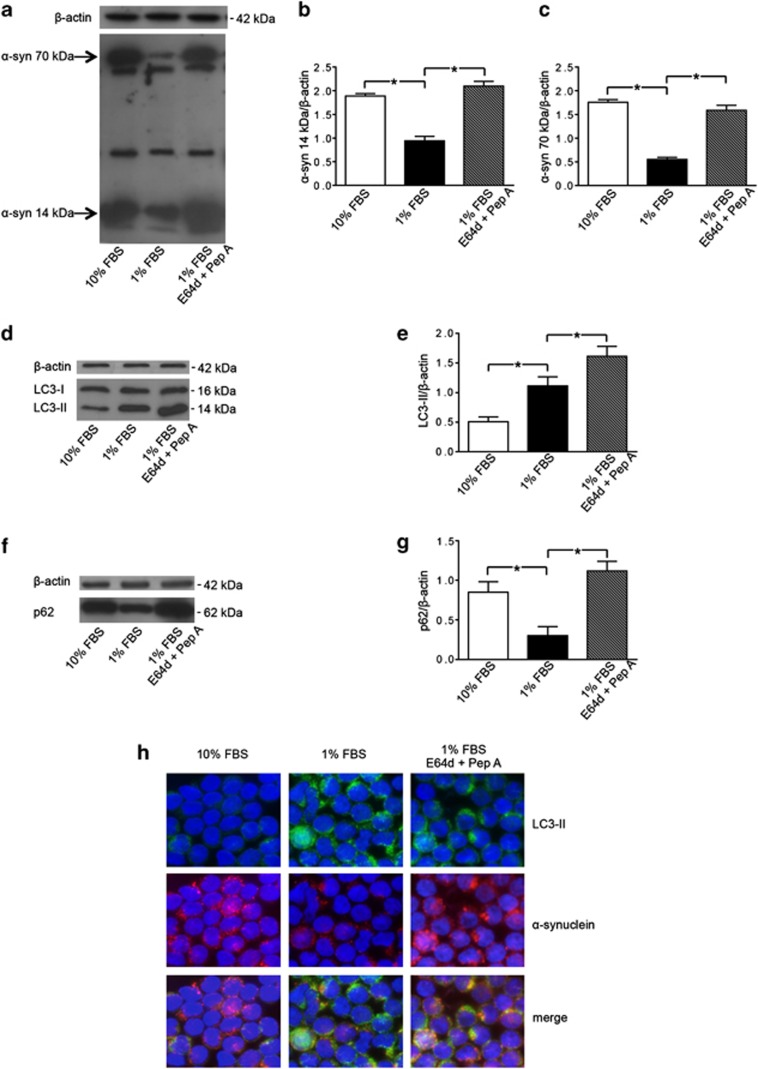

Alpha-synuclein has been reported to form fibrillary aggregates in metabolic impairment conditions.19 Autophagy has been demonstrated to be particularly important for the clearance of these aggregates as it is the only intracellular proteolytic system capable of eliminating insoluble or aggregated α-synuclein forms.9 The signals triggering for the autophagic degradation of α-synuclein could be associated with the ‘intrinsic' status of the protein, that is, its folding state, the presence of post-translational modifications (e.g., ubiquitination) and its solubility.8, 9 In this study, in order to evaluate if autophagy could interfere with the α-synuclein level and degradation of aggregates, T lymphocytes were cultured under growth factor deficiency (serum starvation), a condition that is known to induce metabolic impairment and to trigger autophagy. Alpha-synuclein analyzed by SDS-PAGE showed bands at different molecular weights (Figure 2a). Interestingly, we observed that the levels of the 14- and the 70-kDa bands varied in cells undergoing autophagy. Hence, we focused on the 14-kDa band, which is consistent with the monomeric size, and on the 70-kDa band, which is consistent with an aggregate form susceptible to autophagy degradation (Figures 2b and c). T lymphocytes cultured in 1% FBS showed significant decreased levels of α-synuclein (both the monomeric form and the aggregates) compared with those observed in T lymphocytes cultured in 10% FBS (−51% for the14-kDa α-synuclein, and −75% for the 70-kDa α-synuclein, P<0.01 in both cases; Figures 2a–c). Accordingly, LC3-II levels resulted significantly increased in cells under serum starvation (+55%, P=0.008, Figures 2d and e), whereas p62 levels significantly decreased (−60%, P=0.007, Figures 2f and g). In the presence of the lysosomal protease inhibitors E64d and pepstatin A, LC3-II levels further increased (+32%, Figures 2d and e) and p62 returned to basal levels (Figures 2f and g). Moreover, in the same experimental conditions, we detected a significant increase of α-synuclein levels by western blot analysis (Figures 2a–c) and an accumulation of α-synuclein into the autophagosomes by immunofluorescence (Figure 2h, high-magnification micrograph is provided in Supplementary Figure 1), clearly indicating that the degradation of this protein occurred by the autophagy process. Altogether, these results indicate that under metabolic impairment T lymphocytes from healthy subjects undergo an active and functional autophagy providing the prompt degradation of α-synuclein aggregates.

Figure 2.

Alpha-synuclein (α-syn) degradation by autophagy in T lymphocytes. (a) Western blot analysis of α-syn expression in T lymphocytes cultured with (i) 10% FBS, (ii) 1% FBS and (iii) 1% FBS plus lysosomal inhibitors E64d and pepstatin A (Pep A). Blots shown are representative of five independent experiments. The bands of α-syn at 14 kDa (monomeric form) and at 70 kDa (aggregate form) are indicated by the arrows. Densitometry analysis of (b) the monomeric form of α-syn at 14 kDa (α-syn 14 kDa/β-actin) and of (c) the aggregate form of α-syn at 70 kDa (α-syn 70 kDa/β-actin) are shown. Values are expressed as means±S.D. *P<0.05 for T lymphocytes cultured with 1% FBS versus other experimental conditions. (d) Western blot analysis of LC3-II levels in T lymphocytes cultured with (i) 10% FBS, (ii) 1% FBS and (iii) 1% FBS plus E64d and Pep A. Blots shown are representative of five independent experiments. (e) Densitometry analysis of LC3-II levels relative to β-actin (means±S.D.). *P<0.05 for T lymphocytes cultured with 1% FBS versus other experimental conditions. (f) Western blot analysis of p62 levels in T lymphocytes cultured with (i) 10% FBS, (ii) 1% FBS and (iii) 1% FBS plus E64d and Pep A. Blots shown are representative of five independent experiments. (g) Densitometry analysis of p62 levels relative to β-actin (means±S.D.). *P<0.05. (h) Immunofluorescence analysis of α-syn localization in the presence of lysosomal inhibitors. Alpha-synuclein expression (red fluorescence) and LC3-II expression (green fluorescence) in Triton X-100-permeated cells: T lymphocytes cultured with 10% FBS (left panels), 1% FBS (middle panels), 1% FBS plus E64d and Pep A (right panels). Cells were stained with Hoechst dye to reveal nuclei (blue staining). Note the high number of yellow spots suggesting an accumulation of α-syn into autophagosomes in the presence of lysosomal inhibitors (right panel). No yellow spots are instead observable in T lymphocytes cultured with 10% FBS. Magnification: × 3000

Alpha-synuclein oligomers have been demonstrated to accumulate in neurons from patients with neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD, characterized by an autophagy impairment. However, to date, no data have been reported about α-synuclein levels in T lymphocytes from these patients, including PD patients. We thus analyzed freshly isolated T cells from PD patients under autophagic stimulation, that is, under metabolic impairment. A ‘normal' ability to clear α-synuclein aggregates, comparable to that observed in lymphocytes from healthy subjects, was observed in these cells (Supplementary Figure 2).

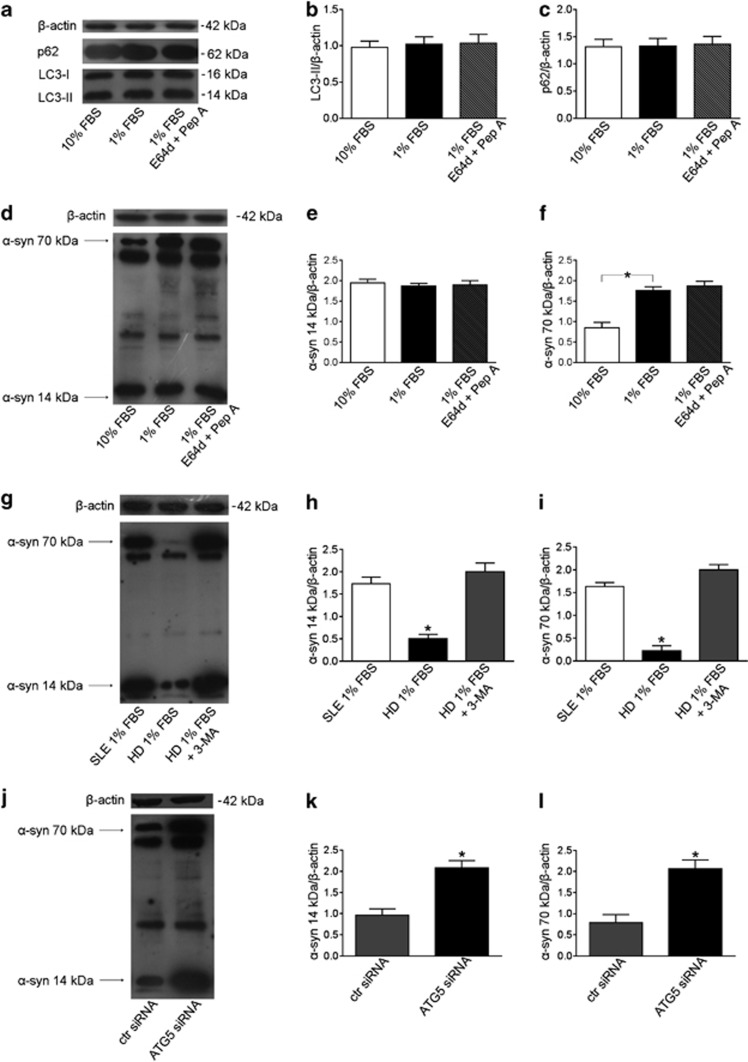

Autophagy impairment leads to accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates

As stated above and recently reported,16 T lymphocytes from SLE patients have been observed to be resistant to autophagy induction, also displaying an upregulation of genes negatively regulating autophagy, including α-synuclein. Basing on these observations, we proceeded to test whether this defective autophagy may account for accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates. We cultivated under serum starvation T lymphocytes from patients with SLE and, as expected, we did not observe any change in LC3-II and p62 levels (Figures 3a–c). Interestingly, in these experimental conditions, a significantly higher level of the aggregate form of α-synuclein in comparison with that observed in T lymphocytes cultured in 10% FBS was detected (+52%, P=0.008, Figures 3d and f). No significant changes were observed for the monomeric 14 kDa α-synuclein (Figures 3d and e).

Figure 3.

Defective autophagy and α-synuclein (α-syn) accumulation in T lymphocytes. (a) Western blot analysis of LC3-II and p62 levels in T lymphocytes from patients with SLE cultured with (i) 10% FBS, (ii) 1% FBS and (iii) 1% FBS plus E64d and pepstatin A (Pep A). Blots shown are representative of 10 independent experiments. Densitometry analysis of LC3-II levels (b) and of p62 levels (c) relative to β-actin. Values are expressed as means±S.D. (d) Western blot analysis of α-syn expression in SLE T lymphocytes cultured with (i) 10% FBS, (ii) 1% FBS and (iii) 1% FBS plus E64d and pepstatin A. Blots shown are representative of 10 independent experiments. The bands of α-syn at 14 kDa (monomeric form) and at 70 kDa (aggregate form) are indicated by the arrows. Densitometry analyses of the monomeric form of α-syn at 14 kDa (e) and of the aggregate form of α-syn at 70 kDa (f) are shown. Values are expressed as means±S.D. *P<0.05. (g) Western blot analysis of α-syn in T lymphocytes from healthy donors (HD) and SLE patients cultured with 1% of FBS. T lymphocytes from HD were cultured in the presence or absence of 3-methyladenine (3-MA). Blots shown are representative of three independent experiments. Densitometry analysis of α-syn at 14 kDa (h) and at 70 kDa (i) relative to β-actin is shown. Values are expressed as means±S.D. *P<0.05 versus other experimental conditions. (j) Western blot of α-syn expression in cell lysates obtained from T lymphocytes transfected with control (ctr) siRNA or with ATG5 siRNA. Blots shown are representative of three independent experiments. Densitometry analysis of α-syn at 14 kDa (k) and at 70 kDa (l) relative to β-actin is shown. Values are expressed as means±S.D. *P<0.05 versus other experimental conditions

The lack of increased LC3-II levels under autophagic stimulation in T lymphocytes from SLE patients could be due either to an autophagy defect or, as suggested in other experimental settings,17 to a very high lysosomal degradation capacity leading to a prompt disappearance of LC3-II. To clarify this point, serum starvation experiments, in the presence of the lysosomal protease inhibitors E64d and pepstatin A, were performed. At variance with T lymphocytes from healthy subjects, LC3-II levels remained unchanged in SLE T lymphocytes. Furthermore, under serum starvation, the levels of p62 and of the monomeric and aggregated forms of α-synuclein remained unchanged even in the presence of E64d and pepstatin A (Figures 3a–f). These results seem to suggest an autophagy defect in T cells from SLE patients (Figures 3a–c). Notably, the treatment of T lymphocytes from healthy donors with the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine, under serum starvation, led to a significant increase of α-synuclein (P<0.01, Figures 3g–i), mimicking the condition observed in SLE lymphocytes. To further demonstrate the specific role of autophagy in α-synuclein degradation, we inhibited the autophagic process knocking down ATG5 by specific siRNA in T lymphocytes. Also in these conditions we observed a significant LC3-II reduction (P<0.01, data not shown) and a significant increase of α-synuclein levels (+54% for the 14 kDa α-synuclein, and +62% for the 70 kDa α-synuclein, P<0.01 in both cases; Figures 3j–l), strongly supporting the assumption that a defective autophagy leads to the accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates.

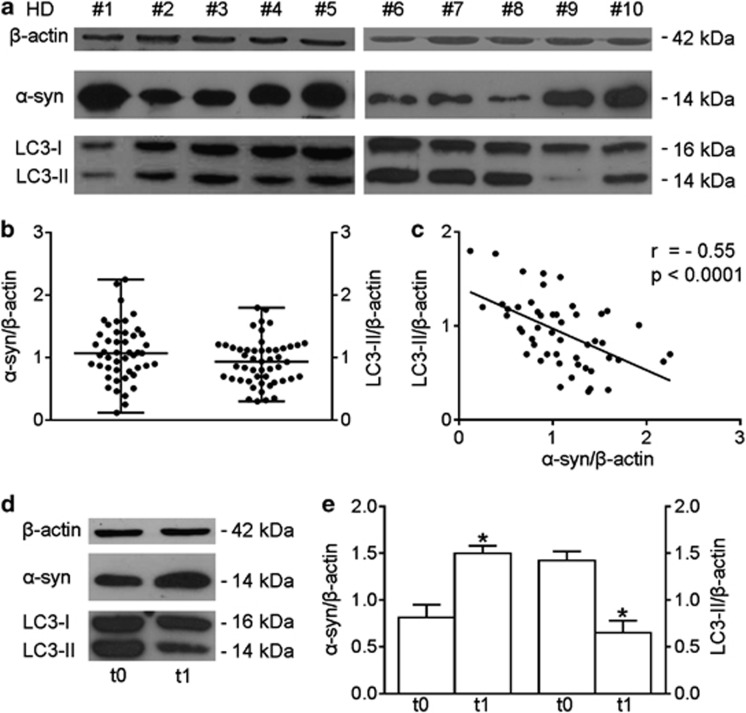

Alpha-synuclein as an autophagy-related marker in primary human T lymphocytes

Monitoring autophagy in vivo or in organs is a poorly developed investigation area at present.18 To verify the potential value of α-synuclein as an autophagy-related marker in freshly isolated T lymphocytes, we examined these cells for LC3-II and the monomeric form of α-synuclein by western blot, and evaluated the possible correlation between these two parameters. The time required for isolation of lymphocytes was constant (2–3 h) in all subjects, and biological samples were isolated and studied immediately after blood drawing. As shown in Figures 4a and b, a high interindividual variability for both α-synuclein and LC3-II levels was present in T lymphocytes. Interestingly, we found a significant inverse correlation between α-synuclein and LC3-II levels (r=−0.55, P<0.0001, Figure 4c), suggesting the possibility to use α-synuclein as straightforward autophagy-related marker in T lymphocytes and immunopathology studies. Unexpectedly, the analysis of p62 and of the p62-like protein NBR1 in freshly isolated T lymphocytes failed to reveal any correlation with either LC3-II or α-synuclein levels, denying the usefulness of these proteins as markers to evaluate basal autophagy in T lymphocytes and suggesting that the expression levels of p62 and NBR1 can also be changed independently of autophagy (Supplementary Figure 3).17

Figure 4.

Alpha-synuclein (α-syn) expression and autophagy in freshly isolated T lymphocytes. (a) Alpha-synuclein and LC3-II western blot analysis of T lymphocyte lysates. Blots shown are representative of independent experiments performed in T lymphocytes from healthy donors (HDs; n=50). (b) Densitometry analysis of α-syn and LC3-II levels relative to β-actin is shown (median with range is presented). (c) Correlation and linear regression analysis of α-syn and LC3-II levels relative to β-actin, r=−0.55, P<0.0001. (d) Alpha-synuclein and LC3-II western blot analysis of cell lysate from T lymphocytes obtained from 1 out of 10 patients with lymphoma. Two time points are shown, that is, before (t0) and after 1 month (t1) of therapy with the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib. (e) Densitometry analysis of α-syn and LC3-II in patients (n=10) before (t0) and after 1 month (t1) of therapy is shown. Values are expressed as means±S.D. *P<0.05. ctr, control; r, Spearman's rho

The possibility of using α-synuclein as an autophagy-related marker was also demonstrated through the measurement of α-synuclein levels in T lymphocytes from lymphoma patients before and after 1 month of therapy with an autophagy modulator, that is, the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib.20 This study was embedded in a phase II clinical trial studying the safety and activity of sorafenib in patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoproliferative disorders.21 Guidetti and co-workers found that LC3-II levels at baseline were significantly higher in responsive patients than in non-responsive patients and peripheral lymphocytes from the responsive patients showed a significant reduction in LC3-II levels after 1 month of therapy.21 Hence, LC3-II represents a predictive marker associated with a favorable outcome of lymphoma patients treated with sorafenib. Here, we found that changes of LC3-II levels were paralleled by changes in α-synuclein levels, assigning also to α-synuclein a role as predictive marker of treatment efficacy (Figures 4d and e).

Discussion

We provide evidence that α-synuclein could be considered as a key player in the mechanism of autophagy of primary human T lymphocytes. Our results indicate that: (i) α-synuclein could be considered as a ‘negative regulator' of autophagy, (ii) the aggregated form of α-synuclein, once formed, can be degraded by autophagy in T lymphocytes from healthy subjects but, (iii) alterations of this degradative molecular pathway, as it occurs in SLE, can result in the abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein, which, as in neurons,22 may represent both a cause and a consequence of impaired autophagic process and, finally, (iv) α-synuclein could represent a valuable tool for the evaluation of autophagy in primary T lymphocytes.

The study of autophagy in primary lymphocytes, although of great interest in translational medicine, has scantily been developed partially because they represent a very complex cell type for the study of this process.16, 21, 23, 24, 25 Actually, primary lymphocytes display a series of pitfalls due, among others, to: (i) the presence of different subpopulations with distinct features and functions, (ii) the activation processes which modify their function, (iii) the difficulties in culturing these cells and (iv) the peculiar very high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, that is, the very small cytoplasmic milieu.

All in all, this is the first demonstration of the close link between α-synuclein and autophagy in human primary T lymphocytes. Alpha-synuclein seems to act as a negative regulator, as demonstrated by experiments carried out with siRNA to knock down α-synuclein gene. In fact, in these experimental conditions, autophagy-related markers were found significantly increased. Importantly, blocking LC3-II/autophagosome degradation by using lysosomal protease inhibitors,17 we observed a further increase of LC3-II levels in α-synuclein knocked down T cells. This clearly suggests that the increased LC3-II levels were not due to an alteration of the lysosomal degradation pathway. A second important point deals with the double-edged role of α-synuclein, that is, with the assumption that it may represent both a cause and a consequence of impaired autophagic process.9 On one hand, it could be hypothesized that autophagy contributes to α-synuclein turnover, and alterations of this proteolytic pathway may result in α-synuclein accumulation because of its impaired clearance. This was evident in T lymphocytes from SLE patients where a resistance to autophagy induction, previously observed,16 has now been better characterized. This autophagy defect appeared to be associated to an accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates. Notably, in the presence of lysosomal inhibitors, no significant changes in the levels of both LC3-II and α-synuclein aggregates were detected. This was probably determined by a block of the autophagy process before autophagosome formation occurring in T cells from SLE patients. Further studies appear, however, mandatory in order to point out the specific step in which autophagy is defective in these cells.

On the other hand, increased α-synuclein protein burden may impair autophagy, generating thus a bidirectional positive feedback loop. Consistently with our results, Winslow et al.10 demonstrated that α-synuclein overexpression impairs autophagy. These authors, by the use of different cultured cell lines (that is, human neuroblastoma cells, SKNSH and human cervical carcinoma cells, HeLa), found a mechanistic basis of the connection between α-synuclein and autophagy via Rab1a inhibition that causes mislocalization of the autophagy protein Atg9, and decreases autophagosome formation. More recently, Song et al.,26 using rat PC12 cells, showed that α-synuclein could also impair autophagy by binding to and blocking the high-mobility group box 1, a protein that has been described to promote autophagy.27 It is conceivable that similar mechanisms could take place also in freshly isolated T cells, although no data are available in this regard yet.

A further important point in this scenario is referred as to T-cell apoptotic susceptibility. In fact, the balance between autophagy and apoptosis, that is, the cross talk between these two pathways, could be pivotal in determining cell fate.28, 29 In particular, T lymphocytes from patients with SLE are known to display an enhanced spontaneous apoptosis and an autophagic resistance.16, 30 On the basis of our results, obtained either in freshly isolated cells from healthy donors or from patients with SLE, the hypothesis that α-synuclein could represent an important molecule involved in both these processes with opposite functions cannot be ruled out.

In the present work, we also demonstrate that, thanks to its role in the autophagic process, α-synuclein may represent a useful marker to evaluate autophagy in T lymphocytes isolated from peripheral blood. This finding could be of importance from a clinical point of view. In fact, drugs that potentially modulate autophagy, such as the mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and derivatives), are increasingly being used in clinical trials, and screenings are being performed for new drugs that can modulate autophagy for therapeutic purposes, particularly in immune-mediated diseases.13, 31, 32 Clearly, it is important to determine whether these drugs are truly affecting autophagy based on a set of accepted criteria and the use of multiple and valuable markers has been recommended.18 Hence, on the basis of our results, we can suggest that α-synuclein could represent a useful predictive marker of the therapeutic response to autophagy-modulating drugs.

Finally, this study opens new perspectives for therapeutic strategies in those immune diseases characterized by autophagy impairment, such as SLE, by reducing α-synuclein synthesis and aggregation or by increasing α-synuclein clearance, for example, developing small-molecule inhibitors of α-synuclein assembly.1, 33, 34

Materials and Methods

Blood samples

Blood samples were obtained from 60 healthy donors (35 women and 25 men; median age of 38 years (range 21–66 years)) and from 10 patients with SLE (7 women and 3 men; median age of 40 years (range 24–55 years)) attending the Lupus Clinic of ‘La Sapienza' University of Rome, Italy. All SLE patients fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of SLE.35 Clinical characteristics of lymphoma patients (n=10) were previously reported.21 Peripheral blood lymphocytes from six patients with PD, randomly selected from the patients admitted to the ‘Laboratory of Clinical and Behavioral Neurology' of Fondazione Santa Lucia, Rome, and to the Movement Disorder Unit, Sant'Andrea Hospital ‘La Sapienza' University of Rome, Italy. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the local ethic committee approved the study.

Cell purification and cell cultures

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll–Hypaque density-gradient centrifugation. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) medium with 10% FBS (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 2 mM glutamine (EuroClone, Pero, Milan, Italy) and 50 μg/ml gentamycin (EuroClone). Immunomagnetic negative selection kit from Miltenyi (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) was used to purify CD3+ T lymphocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Purity of isolated cells, assessed by flow cytometer, reached routinely at least 97%. For serum-starvation experiments, cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1% FBS for 4 h (time chosen on the basis of preliminary time course experiments for 2–24 h; data not shown). Where indicated, cells were treated in the presence of lysosomal inhibitors E64d and pepstatin A (both at 10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 2 h before the end of culture. For inhibition of autophagy, cells were treated with 10 mM 3-methyladenine (Sigma-Aldrich) during the 4 h of serum starvation.

RNA interference transfection in human T lymphocytes

The silencing of α-synuclein was performed with a chemically synthesized siRNA (5′-AACAGTGGCTGAGAAGACCAA-3′ Qiagen, Milan, Italy) and a control siRNA (Qiagen) with a random sequence not present in the human genome (5′-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′).36 107 T lymphocytes, resuspended in 100 μl of the Amaxa Nucleofector kit solution (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA), were electroporated with 5 μg of the indicated siRNA using the V-024 program of the Nucleofector (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Cells were then incubated in complete medium for 24 h before harvesting and the level of α-synuclein silencing was analyzed by both flow cytometry and western blot analyses. For ATG5 silencing, the specific siRNA 5′-AACCTTTGGCCTAAGAAGA-3′ (Qiagen) was used.

Flow cytometry

Intracellular phenotyping of purified T cells was performed as previously described.37 Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with FACS permeabilizing solution (BD BioSciences, San Jose, CA, USA; 340973), washed and stained. Alpha-synuclein expression was detected using anti-α-synuclein (1 μg × 106 cells, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; S5566) monoclonal antibody (mAb) and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Fab specific, Sigma, F2653) as a secondary antibody. An appropriate isotype control antibody (Sigma, M5409) was used. Acquisition was performed on a FACSCalibur (BD BioSciences) and data were analyzed using the CellQuest Pro software (BD BioSciences).

SDS-PAGE and western blot

Purified T lymphocytes were lysed in RIPA buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM MgCl2) in the presence of complete protease-inhibitor mixture. Protein content was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA, USA). For α-synuclein detection, lymphocyte lysate (30 μg) was loaded in SDS-PAGE. As α-synuclein monomers tend to easily detach from blotted membranes, resulting in no or very poor detection, after western blot analysis, nitrocellulose membrane was fixed by incubation for 30 min with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.4% paraformaldehyde.38 As primary antibody, a mouse mAb specific to α-synuclein (Sigma-Aldrich) was used. For LC3-II, p62 and NBR1 protein detection, rabbit anti-human LC3B (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), rabbit anti-human p62/SQSTM1 (Sigma-Aldrich) and rabbit anti-human NBR1 (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies were used. Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad Laboratories) or anti-mouse IgG (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used as secondary antibodies and the reactions were developed using the ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). To ensure the presence of equal amounts of protein, the membranes were reprobed with a rabbit anti-human β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Quantification of protein expression was performed by densitometry analysis of the autoradiograms (GS-700 Imaging Densitometer, Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Immunofluorescence experiments

An indirect immunofluorescence assay was developed on peripheral blood T lymphocytes. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated for 1 h with a rabbit anti-human LC3B (Cell Signaling Technology) antibody and a mouse anti-α-synuclein mAb (Sigma). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies) were used as secondary antibodies. For nuclear staining, the Hoechst 33258 dye (Sigma-Aldrich) was used. Samples were analyzed by using an Olympus U RFL microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Images were acquired using a Hamamatsu digital camera.

Ultrastructural analyses

For transmission electron microscope examination, cells were fixed in 2.5% cacodylate-buffered (0.2 M, pH 7.2) glutaraldehyde (TAAB Laboratories, Berkshire, UK) for 20 min at room temperature and post-fixed in 1% OsO4 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) in cacodylate buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Fixed specimens were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol solutions and embedded in Agar 100 (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Ultrathin sections were collected on 200-mesh grids and counterstained with uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and lead citrate. Sections were observed with a Philips 208 electron microscope at 80 kV (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands). Morphometric analyses were carried out on the basis of previously proposed methodology.39 Forty cell sections per condition were examined at the same magnification ( × 8000) on different 300 mesh grids obtained from different resin blocks in order to avoid counting the same cell several times. We evaluated the number of cells displaying at least two frankly autophagic vacuoles. In particular, vacuoles characterized by a double membrane, barely detectable in lymphocytes, or by the absence of ribosomes in cytosolic side of the vacuole, that is, excluding rough endoplasmic reticulum vesicles, and, mainly, vacuoles containing organelle remnants or semi-digested materials were considered (see Supplementary Figure 4). Only cells displaying intact mitochondria were taken into account. At least 50 different cells were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed on SPSS Inc. (Chicago, IL, USA; version 14.0). The Mann–Whitney unpaired test was used to compare quantitative variables in different groups. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was applied for calculation of the correlation between parallel variables in single samples. Linear regression analysis was used to display a best fit line to the data. For morphometric analyses, the values found in control and specific siRNA-transfected cells were analyzed by using paired t-test. P values<0.05 were considered as significant.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by grants from AIRC to WM (MCO – 9998 and 11505) and from the Italian Ministry of Health to EO (U7A). CC and LT are supported by Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla-FISM-Cod. 2011/R/36 (Genova, Italy).

Glossary

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- PD

Parkinson's disease

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by T Brunner

Supplementary Material

References

- Lashuel HA, Overk CR, Oueslati A, Masliah E. The many faces of alpha-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Jeon BS, Heo C, Im PS, Ahn TB, Seo JH, et al. Alpha-synuclein induces apoptosis by altered expression in human peripheral lymphocyte in Parkinson's disease. FASEB J. 2004;18:1615–1617. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1917fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EC, Cho SE, Lee DK, Hur MW, Paik SR, Park JH, et al. Expression patterns of alpha-synuclein in human hematopoietic cells and in Drosophila at different developmental stages. Mol Cells. 2000;10:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s10059-000-0065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia LV, Kalia SK, McLean PJ, Lozano AM, Lang AE. Alpha-synuclein oligomers and clinical implications for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:155–169. doi: 10.1002/ana.23746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekrellis K, Xilouri M, Emmanouilidou E, Rideout HJ, Stefanis L. Pathological roles of alpha-synuclein in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1015–1025. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:931–937. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Klionsky DJ. Protein turnover via autophagy: implications for metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:19–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelender S. Ubiquitination of alpha-synuclein and autophagy in Parkinson's disease. Autophagy. 2008;4:372–374. doi: 10.4161/auto.5604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Vicente M, Vila M. Alpha-synuclein and protein degradation pathways in Parkinson's disease: a pathological feed-back loop. Exp Neurol. 2013;247:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow AR, Chen CW, Corrochano S, Acevedo-Arozena A, Gordon DE, Peden AA, et al. Alpha-synuclein impairs macroautophagy: implications for Parkinson's disease. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:1023–1037. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod IX, Jia W, He YW. The contribution of autophagy to lymphocyte survival and homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2012;249:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierdominici M, Vomero M, Barbati C, Colasanti T, Maselli A, Vacirca D, et al. Role of autophagy in immunity and autoimmunity, with a special focus on systemic lupus erythematosus. FASEB J. 2012;26:1400–1412. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-194175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XJ, Zhang H. Autophagy in immunity: implications in etiology of autoimmune/autoinflammatory diseases. Autophagy. 2012;8:1286–1299. doi: 10.4161/auto.21212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Galluzzi L, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Autophagy and cellular immune responses. Immunity. 2013;39:211–227. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri C, Barbati C, Vacirca D, Piscopo P, Confaloni A, Sanchez M, et al. T lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus are resistant to induction of autophagy. FASEB J. 2012;26:4722–4732. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-206060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3:542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci A, Collo G, Sarnico I, Battistin L, Missale C, Spano P. Alpha-synuclein aggregation and cell death triggered by energy deprivation and dopamine overload are counteracted by D2/D3 receptor activation. J Neurochem. 2008;106:560–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YH, Ding ZB, Zhou J, Hui B, Shi GM, Ke AW, et al. Targeting autophagy enhances sorafenib lethality for hepatocellular carcinoma via ER stress-related apoptosis. Autophagy. 2011;7:1159–1172. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti A, Carlo-Stella C, Locatelli SL, Malorni W, Pierdominici M, Barbati C, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012;158:108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni C, Lewis PA. Dysfunction of the autophagy/lysosomal degradation pathway is a shared feature of the genetic synucleinopathies. FASEB J. 2013;27:3424–3429. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-223842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerland LM, Genestier L, Peyrol S, Michallet MC, Hayette S, Urbanowicz I, et al. Autolysosomes accumulate during in vitro CD8+ T-lymphocyte aging and may participate in induced death sensitization of senescent cells. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadwal K, Alegre-Abarrategui J, Watson AS, Pike L, Anbalagan S, Hammond EM, et al. A novel method for autophagy detection in primary cells: impaired levels of macroautophagy in immunosenescent T cells. Autophagy. 2012;8:677–689. doi: 10.4161/auto.18935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He MX, He YW. A role for c-FLIP(L) in the regulation of apoptosis, autophagy, and necroptosis in T lymphocytes. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:188–197. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JX, Lu JH, Liu LF, Chen LL, Durairajan SS, Yue Z, et al. HMGB1 is involved in autophagy inhibition caused by SNCA/alpha-synuclein overexpression: a process modulated by the natural autophagy inducer corynoxine B. Autophagy. 2013;10:144–154. doi: 10.4161/auto.26751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Liu K, Yu Y, Xie M, Kang R, Vernon P, et al. Targeting HMGB1-mediated autophagy as a novel therapeutic strategy for osteosarcoma. Autophagy. 2012;8:275–277. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.2.18940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djavaheri-Mergny M, Maiuri MC, Kroemer G. Cross talk between apoptosis and autophagy by caspase-mediated cleavage of Beclin 1. Oncogene. 2010;29:1717–1719. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg-Lerner A, Bialik S, Simon HU, Kimchi A. Life and death partners: apoptosis, autophagy and the cross-talk between them. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:966–975. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy G, Koncz A, Perl A. T- and B-cell abnormalities in systemic lupus erythematosus. Crit Rev Immunol. 2005;25:123–140. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v25.i2.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez D, Bonilla E, Mirza N, Niland B, Perl A. Rapamycin reduces disease activity and normalizes T cell activation-induced calcium fluxing in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2983–2988. doi: 10.1002/art.22085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LA, Younes A. Targeting oncogenic and epigenetic survival pathways in lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2365–2376. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.780288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M, Suzuki N, Taniguchi S, Oikawa T, Nonaka T, Iwatsubo T, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of alpha-synuclein filament assembly. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6085–6094. doi: 10.1021/bi0600749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK, Kotia V, Ghosh D, Mohite GM, Kumar A, Maji SK. Curcumin modulates alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4:393–407. doi: 10.1021/cn3001203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habig K, Walter M, Stappert H, Riess O, Bonin M. Microarray expression analysis of human dopaminergic neuroblastoma cells after RNA interference of SNCA—a key player in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. 2009;1256:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti T, Maselli A, Conti F, Sanchez M, Alessandri C, Barbati C, et al. Autoantibodies to estrogen receptor alpha interfere with T lymphocyte homeostasis and are associated with disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:778–787. doi: 10.1002/art.33400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BR, Kamitani T. Improved immunodetection of endogenous alpha-synuclein. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros F, Arnold J, Page N, Decossas M, Korganow AS, Martin T, et al. Macroautophagy is deregulated in murine and human lupus T lymphocytes. Autophagy. 2012;8:1113–1123. doi: 10.4161/auto.20275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.