Abstract

Objective: The early intervention in psychosis literature has recently appropriated clinical terms with etiologic implications such as staging and pluripotent from the oncology literature without adopting the methodological rigor of oncology research. Oncology research maintains this rigor, among other methods, by examining the literature for evidence of bias and spin, which obscures negative trials. This study was designed to detect possible use of reporting bias and spin in the early intervention in psychosis literature.

Data Sources: Articles were selected from PubMed searches for early intervention in psychosis, duration of untreated psychosis, first-episode psychosis, ultra-high risk, and at risk mental state between January 1, 2000, and May 31, 2013.

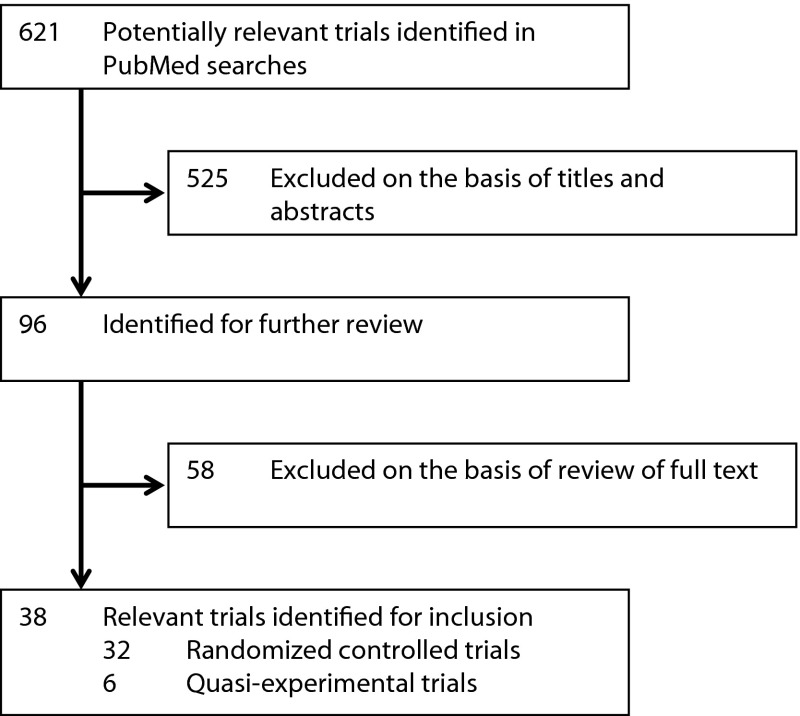

Study Selection: 38 RCT and quasi-experimental articles reporting results from early intervention in psychosis paradigms were selected for inclusion.

Data Extraction: Articles were examined for evidence of inappropriate reporting of primary and secondary end points in the abstract (reporting bias) and presentation as positive despite negative primary end points (spin).

Results: While only 13% of early intervention articles reported positive primary end points, abstracts implied that 76% of articles were positive. There was evidence of bias in 58% of articles and spin in 66% of articles.

Conclusions: There was a high prevalence of spin and bias in the early intervention in psychosis literature compared to previous findings in the oncological literature. The most common techniques were changing the primary end point or focusing on secondary end points when the primary end point was negative and reporting analyses using only a subset of the data. There appears to be a need for greater scrutiny of the early intervention in psychosis literature by editors, peer reviewers, and critical readers of the literature.

Clinical Points

⊠ Current evidence suggests that early intense intervention in patients with psychosis is not disease-modifying but reduces symptoms and improves function while the intense support continues.

⊠ Despite strong claims to the contrary, early intervention with antipsychotics or cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients at high risk of psychotic illness has not been shown to prevent transition to psychosis, although it may delay diagnosis.

⊠ In the absence of disease-modifying interventions, clinical focus should remain on reducing distress and improving function, rather than preventing transition to psychosis or neurodegeneration.

⊠ The high prevalence of spin and bias in clinical trials requires evidence-based practitioners to prefer robust effect sizes in trials with adequate power and consistent replication by independent research groups.

Early intervention in psychosis involves 3 related endeavors based on the often implicit assumptions that psychosis is a degenerative illness and that its progress can be arrested or reversed by treatment.1 These assumptions suggest that it may be possible to detect people who will develop psychotic illness in the future and prevent transition to psychosis (the ultra–high-risk paradigm),2 that reducing the duration of untreated psychosis in people with frank psychotic illness will improve outcomes (the duration of untreated psychosis paradigm),3 and that more intensive treatment starting at the time of detection of psychosis will improve outcomes (the early intervention paradigm).4

There is limited evidence that these paradigms sustainably reduce or prevent psychotic illness compared to treatment as usual.5 Nevertheless, there has been an appropriation of concepts and language from oncology to support the expansion of early intervention services, particularly the notion of clinical staging.6 Although the concept of staging has an intuitive appeal to health care professionals, its application to psychosis may be misleading. While the progressive nature of many cancers is demonstrated by well-defined etiologies with histopathological, imaging, and genetic tests, as well as effective treatments in some circumstances, psychotic illness is characterized by syndromes of poorly differentiated pathology with no confirmatory tests and no definitive treatment. Even if it is assumed that there are stages of psychotic illness, there is no convincing evidence that treatment can prevent a particular patient’s progress through stages, as opposed to reducing symptoms and increasing function at the time of treatment.5

Recently, it was reported that the ultra–high-risk state, in the guise of an “attenuated psychosis syndrome,” was kept out of the DSM-5 because of inadequate diagnostic reliability.7 Although it appears sensible to question the application of a staging model to a paradigm in which it is not possible to diagnose or predict movement between stages, the authors suggested that this poor reliability was evidence of a “pluripotent” risk syndrome. That is, having noted the failure to demonstrate that subclinical psychotic symptoms associated with distress can usefully predict, or that treatment can prevent transition to, psychotic illness, they suggest that the focus should shift to the prediction of nonspecific illnesses from nonspecific distress, opening “preventive possibilities...across this spectrum of evolving illness.”7(p1,132) The use of the word pluripotent appears particularly inappropriate given its clear etiologic implications when used in oncological practice.

It is regrettable that the appropriation of oncological phrases has not led early intervention research to similarly rigorous investigation of theories and treatments. The concept of staging in oncology has a well-established and rich literature to guide definitions and practice. The early intervention in psychosis literature, by contrast, is small and rarely or never provides definitive results or replication of positive effects.5 There is 1 large, well-designed randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining intensive intervention in first-episode psychosis, which concluded at 5 years that there was little evidence of lasting change.4 A smaller RCT in a different population essentially replicated this result.8 Early results suggesting that identification of people at ultra-high risk in enriched samples could prevent transition to psychosis have not been supported at longer follow-up in general samples.9 One large quasi-experimental study demonstrated that the effects of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis were not sustained,3 although the interpretation of this research is obscured by the authors’ creation of a new primary end point at the 10-year follow-up.10,11

The strength of empirical evidence is entirely dependent upon the rigor of tests of its hypotheses. The medical and oncological literature demonstrates its commitment to this ideal by critical analysis of its methods and conclusions, exemplified by efforts to identify spin and bias in the reporting of clinical trials.12,13

Vera-Badillo and colleagues12 measured spin and bias in the reporting of clinical trials for women with breast cancer. They note that reporting bias, authors’ tendency to report only favorable results in articles, interacts with publication bias, or the selective publication of positive results, to significantly affect perceptions of treatment efficacy and safety. They describe a specific type of bias, which they call spin, as the “use of reporting strategies to highlight that the experimental treatment is beneficial, despite a statistically nonsignificant difference in the primary end point, or to distract the reader from statistically nonsignificant results.”12(p1) The authors found that 33% of articles used bias and spin to suggest a positive trial despite a negative primary end point.12

Recent examination of the early intervention in psychosis literature has suggested a tendency to bias and spin.10,14 When it is considered that Vera-Badillo and colleagues12 were describing the negative implications of bias and spin in a body of literature with 164 RCTs concerning a single type of cancer, the implications for a collection of literature with 1–2 main studies in each paradigm, with significant methodological limitations, should be clear.

As major public health decisions involving the selective allocation of hundreds of millions of dollars have been taken on the basis of the early intervention in psychosis literature,15 the limitations of this literature, and apparent reluctance to subject it to critical analysis,11 are a significant concern. This study aims to investigate the possible presence of reporting bias and spin in the early intervention in psychosis literature used to promote expansion of early intervention services. It is hypothesized that the main studies will demonstrate a high prevalence of reporting bias and spin.

METHOD

Study Selection

PubMed searches were performed specifying controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial between January 1, 2000 and May 31, 2013 for the phrases early intervention in psychosis, first episode psychosis, ultra-high risk, at risk mental state, duration of untreated psychosis, and early detection of psychosis. Inclusion criteria were defined as controlled trials of 1 of the 3 early intervention in psychosis paradigms defined above (ultra-high risk, duration of untreated psychosis, early intervention) evaluating patient outcomes between groups. Studies were excluded where there were no controls, where they evaluated only nonpatient outcomes (eg, family coping), or where they pooled treatment and control data to predict outcomes.

Measures of Spin and Selective Reporting Bias

The following data were extracted from each study: type of study (ultra-high risk, duration of untreated psychosis, early intervention), year of publication, identification as a registered trial (true/false), primary end point, secondary end points, result of primary end point, other results, presentation as a positive or negative trial in the abstract, reporting bias (selective reporting of positive results in the abstract), and spin (presentation as positive despite negative primary end point). Articles were examined for details of trial registration, and www.clinicaltrials.gov was consulted for trials that did not identify registration. For registered trials, the reported and identified primary end points were compared.

Categories of spin and bias were codified as most representative of 6 different categories:

Reporting improvement in the absence of a control.

Changing the primary end point where the primary end point was negative.

Focusing on secondary end points where the primary end point was negative.

Reporting only a positive subset of data where the whole set was negative.

Post hoc analyses where planned analyses were negative.

Reporting nearly significant differences as positive.

Statistical Analysis

Absolute number and proportion of articles showing bias and spin, with 95% confidence intervals, were calculated in each category and across all categories of the early intervention in psychosis paradigm.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Selected Articles

Of the 621 citations retrieved, 38 were selected for inclusion in the review (Figure 1). Thirty-two were RCTs, and 6 were quasi-experimental in design. Six articles examined the clinical impact of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis with a public health intervention. Thirteen articles examined whether it was possible to affect the transition to psychosis of patients at ultra-high risk of psychotic illness. Nineteen articles reported the effects of intensive intervention in the early stages of psychotic illness.

Figure 1.

Study Selection

Reporting of Primary End Points in Abstracts

As demonstrated in Table 1, 76% of abstracts reported features suggesting that the studies were positive, despite significant primary end point effects in only 13% of articles. Of the 6 duration of untreated psychosis articles, the single article with a positive primary end point was accurately reported, while 4 of the 5 with a negative primary end point were reported as positive studies in the presence of bias and spin. Of the 13 ultra–high-risk articles, 2 were positive, but 9 were reported as positive, with spin or bias present in 8. Of the 19 early intervention articles, 2 were positive, but 15 were reported as positive, with spin or bias in 13.

Table 1.

Spin and Bias in Early Intervention in Psychosis Articlesa

| Type of Study (no. of articles) | Positive Primary End Point | Reporting Bias Present | Spin Present | Article Presented as Positive |

| Duration of untreated psychosis (6)b | 1 (17) [0.4–64.1] | 3 (50) [11.8–88.1] | 5 (83) [35.8–99.6] | 5 (83) [35.8–99.6] |

| Ultra-high risk of psychosis (13)c | 2 (15) [1.9–45.4] | 6 (46) [19.2–74.9] | 8 (62) [31.6–86.1] | 9 (69) [38.6–90.9] |

| Early intervention in psychosis (19)d | 2 (11) [1.3–33.1] | 13 (68) [43.4–87.4] | 12 (63) [38.4–83.7] | 15 (79) [54.4–93.9] |

| Total (38) | 5 (13) [4.4–28.1] | 22 (58) [40.8–73.7] | 25 (66) [48.6–80.4] | 29 (76) [59.8–88.6] |

Values presented as number (%) of articles [95% CI].

Duration of untreated psychosis: quasi-experimental design comparing region with public health intervention to reduce the period of time spent between the onset of a psychotic illness and the initiation of treatment.

Ultra-high risk: randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes of patients at high risk of developing a long-term psychotic illness randomized to treatment as usual versus active interventions including antipsychotic medication, fatty acids, or cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Early intervention in psychosis: randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes in patients with first-episode psychosis randomized to treatment as usual versus early intensive treatment, with low patient to case manager ratios, family psychoeducation, and social skills training.

Bias and Spin Strategies

Overall, 22 of 38 articles contained bias, while 25 used spin. Table 2 categorizes articles by the primary technique of bias or spin. Common techniques included the use of positive secondary end points where the primary end point was negative and the related technique of the substitution of a new primary end point when the original primary end point was negative. Next most common was to report the primary end point for a subset of data where the primary end point was negative for the complete set of data.

Table 2.

Main Bias/Spin Techniques Used in Early Intervention in Psychosis Articlesa

| Category (no. of articles) | Article | Typeb | Bias in Abstract | Spin in Abstract |

| Uncontrolled improvement (4) | Kuipers et al, 200416 | Early intervention in psychosis | None | Implies positive trial by reference to improvements that were no different between treatment and control groups |

| Addington et al, 201117 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | None | Concludes positive trial on the basis of a positive within-groups analysis | |

| McGorry et al, 201318 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | Emphasizes improvements across all groups | Concludes positive trial by reference to improvements that were no different between treatment and control groups | |

| Tarrier et al, 200419 | Early intervention in psychosis | Does not report absence of difference between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive therapy (active control) | Concludes positive trial by reference to improvements that were no different between treatment and control groups | |

| Analyze subset (4) | McGorry et al, 200220 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | Reports post hoc subset analysis of treatment-adherent patients | Concludes positive trial on the basis of subset analysis |

| Morrison et al, 200421 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | Reports positive analysis after post hoc exclusion of 2 patients rather than negative intent-to-treat analysis | Concludes positive trial on the basis of non–intent-to-treat analysis | |

| Tempier et al, 201222 | Early intervention in psychosis | Identifies confounds in parent data set, which made results negative, but does not report this analysis | Concludes positive trial despite identifying confounds, which would make the trial negative | |

| van der Gaag, et al 201223 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | Reports positive non–intent-to-treat analysis rather than negative intent-to-treat analysis in abstract | Concludes positive trial by reference to post hoc analyses, not planned analyses | |

| Change primary end point (8) | Petersen et al, 200524 | Early intervention in psychosis | Primary end point of relapse not reported | Concludes positive trial on basis of newly assigned primary end point, symptoms |

| Petersen et al, 200525 | Early intervention in psychosis | Primary end point of relapse not reported | Concludes positive trial on basis of newly assigned primary end point, symptoms | |

| Thorup et al, 200526 | Early intervention in psychosis | Primary end point of relapse not reported | Concludes positive trial on basis of newly assigned primary end point, symptoms | |

| Larsen et al, 200627 | Duration of untreated psychosis | None | Despite negative primary end point of time to remission, concludes positive trial by reference to secondary end point | |

| Bertelsen et al, 20084 | Early intervention in psychosis | Primary end point of relapse not reported | None | |

| Melle et al, 200828 | Duration of untreated psychosis | Primary end point of time to remission/relapse not reported | Concludes positive trial on basis of new primary end point, symptoms | |

| Larsen et al, 201129 | Duration of untreated psychosis | Primary end point of time to remission/relapse not reported | Concludes positive trial on basis of newly assigned primary end point, symptoms | |

| Hegelstad et al, 20123 | Duration of untreated psychosis | Primary end point of time to remission/relapse not reported; constructed new primary end point, recovery | Concludes positive trial on basis of newly constructed primary end point, recovery | |

| Focus on secondary end points (3) | Nordentoft et al, 200230 | Early intervention in psychosis | Does not report primary end point, suicide-related behaviors | Concludes positive trial by reference to secondary end point, hopelessness |

| Petersen et al, 200731 | Early intervention in psychosis | Reports negative primary end point (odds ratio including 1.0) as positive | Concludes positive trial by reference to secondary end point | |

| Phillips et al, 200732 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | None | Concludes positive trial by speculating on cost savings with no evidence for this in trial | |

| Post hoc analysis (4) | Jackson et al, 200833 | Early intervention in psychosis | Emphasize positive post hoc midtreatment analysis despite negative primary end point | Concludes positive trial by reference to post hoc analyses |

| Gleeson et al, 201334 | Early intervention in psychosis | Reports positive post hoc point comparison rather than negative survival curve for primary end point | Concludes positive trial by reference to point comparison | |

| Berger et al, 200735 | Early intervention in psychosis | Emphasize post hoc analyses suggestive of accelerated treatment response | Concludes positive trial on the basis of positive post hoc analyses and secondary end point | |

| Morrison et al, 200736 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | Emphasize positive post hoc analyses of transition to psychosis over negative planned results | Concludes positive trial on post hoc analyses rather than negative planned analyses | |

| Nearly significant (3) | McGlashan et al, 200637 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | Report nearly significant differences | Concludes positive trial by reference to nearly significant differences in the context of low power |

| Lewis et al, 200238 | Ultra-high risk of psychosis | Report nonsignificant trends as positive and do not identify negative primary end point | On the basis of nonsignificant results, concludes “transient advantages” | |

| Melle et al, 200539 | Duration of untreated psychosis | None | Conclusion does not mention negative result but speculates on possible positive outcomes that have not been demonstrated |

Intent to treat: statistical analyses performed using data from all patients originally assigned to treatment and control conditions. Primary end point: main treatment outcome defined in the original experimental design, such as rate of transition to psychosis. Secondary end point: less important auxiliary outcome defined in the original experimental design, such as symptom scores.

Duration of untreated psychosis: quasi-experimental design comparing region with public health intervention to reduce the period of time spent between the onset of a psychotic illness and the initiation of treatment. Early intervention in psychosis: randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes in patients with first-episode psychosis randomized to treatment as usual versus early intensive treatment, with low patient to case manager ratios, family psychoeducation, and social skills training. Ultra-high risk: randomized controlled trials comparing outcomes of patients at high risk of developing a long-term psychotic illness randomized to treatment as usual versus active interventions including antipsychotic medication, fatty acids, or cognitive-behavioral therapy.

DISCUSSION

There is a high prevalence of reporting bias and spin in the early intervention in psychosis literature across the duration of untreated psychosis, ultra–high-risk, and early intervention paradigms. This finding may be related to the low rate of positive primary end points. Although the rates of spin and bias are surprisingly high in other areas of medicine, the current evidence suggests that, in the early intervention in psychosis literature, spin and bias are present more often than they are absent. The techniques of bias and spin in the early intervention literature are somewhat different compared to the general medical literature.12 Characteristic techniques are illustrated below by examples, while acknowledging that the degree of spin and bias is not uniform across the studies.

Report Uncontrolled Improvements

Several articles reported that an intervention had improved outcomes despite the absence of a significant comparison with a control group, which is necessary to demonstrate that an improvement is not due to simple reversion to the mean or other effects shared by groups. Two variants of this technique are described. McGorry and colleagues18 report an ultra–high-risk intervention wherein 115 patients were randomized to cognitive therapy plus risperidone, cognitive therapy plus placebo, or supportive therapy plus placebo. They also followed a group of patients who refused randomization but were willing to be monitored. The authors report that all randomized groups improved, with no significant between-group differences in the primary end point of transition to psychosis. The authors do not comment on the fact that the group monitored without randomized intervention had the lowest rate of transition to psychosis. They conclude that this is evidence that supportive therapy is effective, despite reporting no control.18 As demonstrated elsewhere, the only valid conclusion is that the addition of cognitive therapy and risperidone to supportive therapy does not improve outcomes.40

Similarly, Addington and colleagues17 report an ultra–high-risk study in which 51 patients were randomized to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or supportive therapy. Although there were no significant between-group differences, the authors conclude that the CBT group showed a more rapid improvement in symptoms on the basis of a significant within-group difference for the CBT but not for the treatment-as-usual group at 5-month follow-up. This is one of the specific forms of bias identified by Vera-Badillo and colleagues: it is invalid to draw conclusions between groups on the basis of within-group tests.12

Change the Primary End Point

One of the more common techniques identified in this study was to change the reported primary end point without acknowledging that the original primary end point was not significantly different between groups. A series of duration of untreated psychosis articles by the Scandinavian Treatment and Intervention in Psychosis Study (TIPS) group changes their primary end point twice between different articles without acknowledging that the original primary end point remained nonsignificant.3,24,27–29,39 The primary end point when the study was designed was rate of relapse. At 1-year follow-up, having reported that relapse was not different between groups, the TIPS group changed the primary end point to symptom scores.24 When symptom scores became nonsignificant at 10-year follow-up, the TIPS group constructed a new primary “recovery” end point.3 Later articles do not acknowledge the changed primary end point or the nonsignificant nature of the original primary end point.3,27–29

Focus on Positive Secondary End Points

A related technique was to distract attention from a negative primary end point by focusing on positive secondary end points. Nordentoft and colleagues30 report a RCT in which 341 patients with first-episode schizophreniform psychosis were randomized to treatment as usual or intensive treatment. Suicide-related behaviors were measured over 1 year. The nonsignificant primary end point of suicide behaviors is not mentioned in the abstract, which instead reports factors that predicted suicide behavior, and notes that the intensive treatment group reported lower hopelessness than the treatment-as-usual group, a secondary end point.30

Analyze a Subset of Data

Several authors distract attention from negative primary end points by reporting positive primary end points for subsets of data. McGorry and colleagues20 report an ultra–high-risk study wherein 59 patients were randomized to treatment as usual or low-dose risperidone. At 6-month follow-up, they found no difference in rate of transition to psychotic illness between groups. Their abstract refers to a significant post hoc analysis comparing the rate of transition in treatment as usual to transition in risperidone-treated patients who were adherent with risperidone treatment. As this subset clearly selects for a characteristic, treatment adherence, associated with better outcomes in schizophrenia, the simplest explanation for their results is that the whole-set analysis accurately reflects no difference between treatment groups, while the subset analysis demonstrates an expected confound due to selection bias.20

Post Hoc Analysis

Another source of reporting bias was to first test overall statistics then, when these were not significant, to test specific comparisons, including ad hoc comparisons, maximizing the possibility of finding significant results. Investigating the possibility of reducing relapse after resolution of a first episode of psychosis, Gleeson and colleagues34 found no difference in survival curves of time to relapse over the 30-month trial. They then performed multiple ad hoc survival curve analyses to individual time points and report a positive trial based on a significant result at 12 months. Given that survival curve analysis is designed to account for the variance at individual time points across the whole period being tested, this is particularly inappropriate.

Nearly Significant Results and Power Analyses

McGlashan et al37 reported “nearly significant” results as evidence of efficacy. They argued that the low power of their study suggested a false-negative result and calculated a number needed to treat (also nonsignificant) to prevent transition to psychosis in ultra–high-risk patients on the basis of a nonsignificant trial.37

Spin in References to the Early Intervention in Psychosis Literature

Early intervention in psychosis advocates have publicly suggested the use of the scientific literature as a tool of rhetoric to advance the movement.41 This suggestion may have fostered the tendency of arguments for the expansion of early intervention psychosis to misrepresent the conclusions of the research they refer to. One prominent early intervention in psychosis researcher1 refers to the results of the OPUS (intensive early intervention program) and Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) groups as evidence for the disease-modifying effects of early intervention. 4,42,43 This assertion contradicts the conclusions of the cited authors, as the OPUS article concludes that “the benefits of the intensive early intervention program after 2 years were not sustainable, and no basic changes in illness were seen after 5 years.”4(pp769–770) While the cited LEO articles were more positive, they were 18-month follow-up reports.42,43 Two years prior to the claim that LEO suggested a disease-modifying effect of early intervention in psychosis, the LEO group had confirmed over longer follow-up the OPUS results, suggesting no disease-modifying effects of early intervention in psychosis.8

Limitations

As established by Vera-Badillo and colleagues,12 there are no objective criteria for the detection of spin and bias. It is also difficult or impossible to demonstrate the specific mechanisms that lead to the presence of spin or bias. It would appear that the possibilities include either consciously or unconsciously motivated behaviors or simple error. To take the most recent article by McGorry and colleagues18 as an example, the conclusion that undifferentiated improvement across all groups implies a treatment effect is clearly an invalid inference and an example of spin as it is defined by Vera-Badillo and colleagues.12 Possible mechanisms would include that the authors were unaware that their conclusion was not supported by their evidence (an error) or that they were aware of this fact but were consciously or unconsciously motivated to present their negative results in a positive light. The current article cannot differentiate between these possibilities, although it may be instructive that the authors do not acknowledge the error in their analysis even when it is explicitly identified.40,44

CONCLUSIONS

Research by Vera-Badillo and others12,13 demonstrates that spin and bias are widespread in oncological and medical literature. The early intervention in psychosis literature appears to include a high prevalence of techniques that tend to obscure negative trials that is particularly concerning in light of the conscious use of rhetoric by prominent early intervention advocates. The construction of a new primary end point at 10-year follow-up by the TIPS group,3 having already changed the primary end point at 1-year follow-up, is the most serious example in the collected literature. The antidote would appear to lie with editors, peer reviewers, and critical consumers of the early intervention literature. The current article suggests that early intervention in psychosis literature should be closely analyzed for evidence of spin or bias and methodological shortcomings identified and acknowledged.

Drug names: risperidone (Risperdal and others).

Potential conflicts of interest: None reported.

Funding/support: None reported.

References

- 1.McGorry PD. Truth and reality in early intervention. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(4):313–316. doi: 10.1177/0004867412442172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Nelson B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra high risk for psychosis: 6-month analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(4):430–440. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04979ora. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hegelstad WT, Larsen TK, Auestad B, et al. Long-term follow-up of the TIPS early detection in psychosis study: effects on 10-year outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):374–380. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: the OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004718.pub3. (6)CD004718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott J, Leboyer M, Hickie I, et al. Clinical staging in psychiatry: a cross-cutting model of diagnosis with heuristic and practical value. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(4):243–245. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.110858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yung AR, Woods SW, Ruhrmann S, et al. Whither the attenuated psychosis syndrome? Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(6):1130–1134. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gafoor R, Nitsch D, McCrone P, et al. Effect of early intervention on 5-year outcome in non-affective psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(5):372–376. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, et al. The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(1):107–120. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amos A. Alternative interpretation for the early detection of psychosis study. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):992. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050578. author reply 992–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amos A. An axeman in the cherry orchard: early intervention rhetoric distorts public policy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47(4):317–320. doi: 10.1177/0004867412471438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vera-Badillo FE, Shapiro R, Ocana A, et al. Bias in reporting of end points of efficacy and toxicity in randomized, clinical trials for women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(5):1238–1244. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boutron I, Dutton S, Ravaud P, et al. Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2058–2064. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castle D. What, after all, is the truth: response to McGorry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(7):685–687. doi: 10.1177/0004867412449297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roxon N, Macklin J, Butler M. National Mental Health Reform-Ministerial Statement. Canberra, Australia: Australian Labour Party;2011:1–38. www.health.gov.au/internet/budget/publishing.nsf/Content/849AC423397634B7CA25789C001FE0AA/$File/DHA%20Ministerial.PDF. Accessed July 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuipers E, Holloway F, Rabe-Hesketh S, et al. Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST). An RCT of early intervention in psychosis: Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(5):358–363. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Addington J, Epstein I, Liu L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;125(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGorry PD, Nelson B, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis: twelve-month outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):349–356. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarrier N, Lewis S, Haddock G, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy in first-episode and early schizophrenia. 18-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(3):231–239. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):921–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185(4):291–297. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tempier R, Balbuena L, Garety P, et al. Does assertive community outreach improve social support? results from the Lambeth study of early-episode psychosis. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(3):216–222. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.20110013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Gaag M, Nieman DH, Rietdijk J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for subjects at ultra-high risk for developing psychosis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(6):1180–1188. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al. A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ. 2005;331(7517):602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38565.415000.E01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen L, Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, et al. Improving 1-year outcome in first-episode psychosis: OPUS trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;187(48):s98–s103. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, et al. Integrated treatment ameliorates negative symptoms in first episode psychosis: results from the Danish OPUS trial. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen TK, Melle I, Auestad B, et al. Early detection of first-episode psychosis: the effect on 1-year outcome. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):758–764. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, et al. Prevention of negative symptom psychopathologies in first-episode schizophrenia: two-year effects of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(6):634–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen TK, Melle I, Auestad B, et al. Early detection of psychosis: positive effects on 5-year outcome. Psychol Med. 2011;41(7):1461–1469. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Abel M, et al. OPUS study: suicidal behaviour, suicidal ideation and hopelessness among patients with first-episode psychosis: one-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2002;181(suppl 43):s98–s106. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al. Substance abuse and first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: the Danish OPUS trial. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2007;1(1):88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Yuen HP, et al. Medium term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2007;96(1–3):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Killackey E, et al. Acute-phase and 1-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial of CBT versus befriending for first-episode psychosis: the ACE project. Psychol Med. 2008;38(5):725–735. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gleeson JFM, Cotton SM, Alvarez-Jimenez M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of relapse prevention therapy for first-episode psychosis patients: outcome at 30-month follow-up. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):436–448. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger GE, Proffitt T-M, McConchie M, et al. Ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(12):1867–1875. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrison AP, French P, Parker S, et al. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):682–687. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):790–799. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis S, Tarrier N, Haddock G, et al. Randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy in early schizophrenia: acute-phase outcomes. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2002;43(suppl 43):s91–s97. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melle I, Haahr U, Friis S, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects on baseline social functioning and quality of life. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(6):469–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amos A. Biased reporting of results in patients at ultra-high risk of psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):1123. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12lr08602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGorry PD, Nordentoft M, Simonsen E. Introduction to “early psychosis: a bridge to the future.”. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187(suppl 48):s1–s3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Craig TKJ, Garety P, Power P, et al. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. BMJ. 2004;329(7474):1067. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38246.594873.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garety PA, Craig TKJ, Dunn G, et al. Specialised care for early psychosis: symptoms, social functioning and patient satisfaction: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(1):37–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGorry PD, Yung AR, Nelson B, et al. Dr McGorry and colleagues reply. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):1123. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13lr08602a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]